Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

Price Discount and Gift Choice: Interplay between Economic and Social Value

Abstract

Purpose: Price discounts are a popular pricing strategy because discounts increase the perceived economic value of a purchase. However, social, rather than economic value is the primary concern in gift choice. Little research examines the interplay between economic and social value in gift choice. This study fills this gap by investigating how price discounts affect gift choice. Design/Methodology: To test the proposed hypotheses, two 2×2 between-subjects experimental designs were conducted. In Study 1, eighty-one undergraduate students participated in the study conducted in a controlled lab setting. A two-way ANOVA was run with purchase intention as the dependent variable, and goal salience and discount as the independent variables. In Study 2, one hundred and fifty undergraduate students participated in the controlled in-laboratory study. A two-way ANOVA was run with purchase intention as the dependent variable, and social cue and economic cue as the independent variables. Findings: The results show that price discounts increase purchase intention when the social value of a gift is not salient (Study 1), and when social environmental cues are not available (Study 2). The findings suggest that consumers prioritize social over economic value in gift choice. However, when social value cannot be determined, consumers choose a gift based on price. Practical Implications: The current study suggests that managers should make social value salient to elicit a higher wiliness to pay from customers especially during gift-giving holidays when the act of gift-giving is considered to enhance the social value between gift giver and recipient. Moreover, the findings suggest that marketers should help consumers assess the appropriateness of a gift based on recipient’s preferences. Originality/Value: The current research shed light on understanding the impact of price discounts on gift choice, as well as the interplay between economic and social value in gift choice.

Keywords

Gift Giving, Social Cues, Price Discount.

Introduction

Consumers often seek to maximize the economic value of their purchases by minimizing the price they pay for their products. For instance, according to a 2019 Loyalty Barometer Report by HelloWorld (2019) 75% of the consumers crave discount and instant offers. 61% of consumers claim that the best way for a company to interact with consumers is by offering instant offers and discounts. Price discounts are seductive because discounts reduce the original price referent and increase the economic value of a purchase (Blattberg & Neslin, 1990; Grewal et al., 1998). Hence, price discounts are decisive factors in many purchase occasions.

However, the effectiveness of price discounts is unclear in gift choice. Gift giving is highly relevant as information technology and online environment facilitate gift giving interactions (Chignell et al., 2013). When choosing a gift for someone else, consumers not only consider economic value, but also social value. Social value refers to the usefulness of a gift to express social meaning, fulfill social obligations, take on a particular social role, or affirm interpersonal relationships (Camerer, 1988; Goodwin et al., 1990; Otnes et al., 1993; Ruth et al., 1999). This social value of gifts is important because it helps societies maintain social norms (i.e., reciprocity) and reaffirm social values through symbolic social conventions (i.e., achievement) (Camerer 1988; Belk & Coon, 1993). Because consumers often purchase gifts with social value in mind, they are willing to sacrifice economic value by paying a price premium (Ghajar-Khosravi et al., 2013). In such case, price discounts should have less impact on gift purchase decisions. But, why are price discounts ubiquitous during gift-giving holidays such as Christmas and Valentine’s Day? Regrettably, extant research has not examined this phenomenon.

This research aims to fill this void by investigating the impact of price discounts on gift choice. To accomplish this goal, the decision-making process for gift choice is delineated. Then, based on information processing heuristics, two experimental studies that test the extent to which economic and social value affect gift choice are presented. The research findings shed light on the interplay between economic and social value in gift choice. In addition, the results contribute to managerial practice by explaining the effectiveness of price discounts in consumers’ gift choice. Understanding this phenomenon is important because gift shopping is a common social activity. For instance, according to the National Trends of Gift Giving Study about 47% of American women purchase gifts at least 10 times a year (Miller & Washington, 2014).

Gift Choice

The gift selection process is consistent with the Consumer Decision Making Model (Solomon, 2012). The process begins by recognizing a need. The need for a gift is rooted in social norms (e.g., reciprocity) and self-expression (e.g., love) and can be triggered by social (e.g., weddings, birthdays) and personal (e.g., anniversaries) events (Larsen & Watson, 2001). Once the need is recognized, consumers search information, evaluate alternatives, choose and purchase a gift, and evaluate their choice.

Materials and Methods

Although this process seems similar to the process of buying anything else, selecting a gift has a simple, yet profound peculiarity: gifts are often purchased for someone else. This aspect makes decision-making more complexes. When choosing products for self-use, consumers search information and evaluate products using their preferences and past experiences as references. When choosing a gift for someone else, consumers have to guess what the recipient wants (Camerer, 1988). Accordingly, consumers have to expend resources such as time, money, and effort to gather information not only about products, but also about the recipient’s preferences. Further, shopping for a gift can be a daunting task as consumers have to consider many other variables such as price, private and public meaning, occasion, functionality, appropriateness, and relationship type (Larsen & Watson, 2001). Thus, in the gift selection process, the stages of information search and product evaluation are more intense. Table 1 for a comparison between personal and gift purchase decisions.

| Table 1: Information Search And Product Evaluation In Personal And Gift Purchase Decisions | ||

| Decision Stage / Purchase type | Personal | Gift (Other) |

|---|---|---|

| Information Search | Information about personal preferences is more accessible. Information search is focused on the product. | Information about others’ preferences is less accessible. Information search is focused on the product, the recipient’s preferences, and the occasion. |

| Product Evaluation | Products are evaluated using personal criteria. | Products are evaluated using a combination of personal criteria, recipient’s estimated criteria, occasion, relationship, and meaning. |

The amount of resources a consumer spends shopping for a gift depends on his/her ability to guess with confidence the overall value of a given gift. For example, when a consumer wants to buy a gift to strengthen a social relationship, social value becomes salient. Thus, the consumer’s goal is to purchase a gift that the recipient favors (Larsen & Watson, 2001; Steffel & LeBoeuf, 2013). In this case, the consumer’s shopping activity will be high when he/she lacks information regarding the recipients’ preferences, has budget constraints, the social convention is unknown, the meaning of the occasion is ambiguous, or the relationship type is not clear. Even when consumers feel that they know the recipient well (e.g., close friend or family member), consumers are willing to perform extensive gift shopping to enhance close social relationships by “guessing” future preferences. Consumers attempt to surprise recipients by uncovering preferences that the recipient did not know she/he had (Camerer, 1988). Overall, gift shopping is a guessing game. The game intensifies when overall gift value is uncertain and the gift-giver is not able to make a confident guess.

Price discounts and gift choice

Price is an important factor in product choice (Chang & Wildt, 1994). Prices are used as referents to assess the economic value of a purchase (Blattberg & Neslin, 1990; Grewal et al., 1998). Accordingly, price discounts are offered to increase consumers’ perceived economic product value, and thus increase purchase intention (Dodds & Monroe, 1985). However, if economic efficiency was the goal for the gift-giver and economic value was the expectation for the recipient, cash would be the most popular gift (Camerer, 1988).

The reason why many consumers still engage in gift shopping is that they seek for a gift that maximizes overall value, including social value. Economic value is only one source of overall value. The current study proposes that in situations when consumers seek to maximize economic value, a price discount will be more effective. For example, when purchasing an item for self-use. But, when consumers seek to purchase a gift for a special person, social value will become more salient than economic value and, as a consequence, consumers will be less affected by price discounts. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: In a condition where economic value is salient, purchase intention for an item will be higher when price discounts are offered than when price discounts are not offered.

H2: In a condition where social value is salient, purchase intention for an item will not depend on whether price discounts are offered.

Study 1

To test the proposed hypotheses, a 2 (Value: economic vs. social) × 2 (Discount: no, yes) between-subjects experimental design was conducted.

Participants and procedures

Undergraduate students are particularly appropriate for the study of gift giving because it is quite common for undergraduate students to purchase self-gifts as well as gifts for others. Eighty-one undergraduate students in a large university in the Southern United States participated in the study in exchange for extra course credit. The study was conducted in a controlled lab setting. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four possible conditions. After evaluating the scenario, participants answered a questionnaire containing the dependent variable and demographics.

The context of the experiment consisted of a gift shopping scenario in which participants had to evaluate several pairs of glasses as a gift choice for a birthday occasion. To make either economic or social value salient, two shopping scenarios were created. In the economic value condition participants were told that they were shopping for a birthday gift for themselves. Since social value is not salient, it is expected that economic value to play a larger role in this purchase decision. In the social value condition, participants were told that they were shopping for a birthday gift for their boss. To increase the social value of the purchase, participants were also told that the sunglasses appeared in their boss’ favorite website.

Discount conditions were manipulated by stating that participants had a total budget of twenty dollars for the gift purchase and then showing either a non-discounted or a discounted price. The no discount condition showed a non-discounted price of $20. For the price discount condition, an original price of $40 dollars was shown along with a 50% discount. The final price was marked at $20. To measure purchase intention, this paper adapted Yi’s (1990) scale. Participants were asked: “How likely are you to consider purchasing this gift?" Participants rated four items in a 7-point scale with 1 anchored to “not at all, definitely not intend, very unlikely, and impossible” to 7 “definitely yes, definitely intend to, very likely, very possible” (α= 0.97).

Hypothesis Testing

total of 66 responses were included in the analysis; 15 cases were excluded due to severe missing data or because they responded to filter questions such as “if you read this question, leave it blank” or “if you are reading please do not respond to this question” or “leave this question blank.” These filter questions were interspersed within the survey (DiLalla & Dollinger, 2006). Cell sizes ranged from 10 to 20. Table 2 shows the cell conditions.

| Table 2: Cell Sizes And Mean Differences Across Conditions In Study 1 | |||

| Economic value (self-use) | Without Discount | With Discount | With vs. Without Discount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Size | 19 | 17 | |

| Mean | 3.05 | 4.87 | p = 0.001 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.57 | 1.44 | |

| Social value (gift for boss) | |||

| Cell Size | 20 | 10 | |

| Mean | 5.13 | 5.78 | p > 0.2 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.76 | 1.50 | |

| Purchase for Self vs. Others | p < 0.001 | p > 0.1 | |

H1 stated that in the economic value condition, purchase intention should be higher for the discount than for the no discount condition. H2 posited that in the social value condition, purchase intention should be the same across discount conditions. To test these hypotheses a two-way ANOVA was run with purchase intention as the dependent variable, and goal salience and discount as the independent variables.

The results show that there was not a significant interaction effect (F (1, 62) = 2.07, p = 0.16). The main effects of value (F (1, 62) = 13.51, p < 0.001) and discount (F (1, 62) = 9.25, p = 0.003) were significant. Pairwise comparisons were used to test the hypotheses and compare the effect of discounts in social versus economic value conditions.

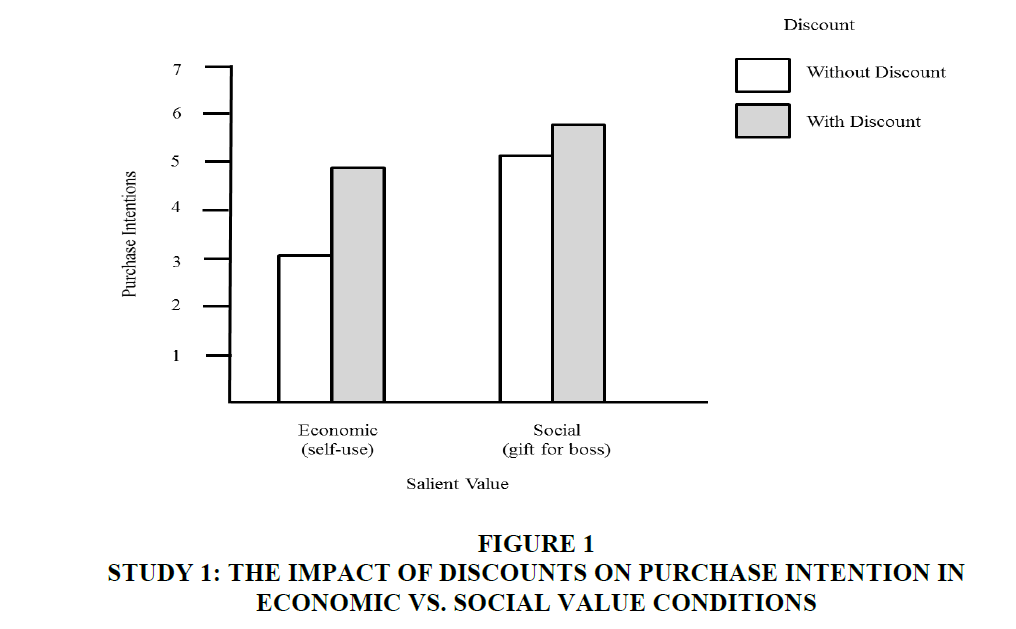

The results from the pairwise comparisons showed that when economic value was salient, there was a significant difference between the no discount and discount condition. Specifically, purchase intention was higher in the discount (M = 4.87) condition than in the no discount (M = 3.05) condition (F (1, 62) = 11.76, p = 0.01). Thus, H1 was supported. In addition, the results showed that when social value was salient, purchase intention was not significantly different across no discount (M = 5.13) and discount (M = 5.78) conditions (F (1, 62) = 1.121, p = 0.29). Hence, H2 was also supported. Furthermore, the results showed that in the no discount condition, purchase intention was significantly higher in the social (M = 5.13) rather than in the economic value (M = 3.05) condition (F (1, 62) = 16.65, p < 0.001). This finding confirms that when the discount was not offered, individuals were more prices conscious when they were purchasing a gift for themselves, but less price conscious when they were buying a gift for their boss. Figure 1 depicts the findings.

Figure 1:Study 1: The Impact Of Discounts On Purchase Intention In Economic vs. Social Value Conditions.

Results of Study 1

The results of Study 1 suggest that in self-use purchases, price discounts increase purchase intention. However, in choosing a gift for someone else, individuals’ purchase intention for an appropriate gift is high even if no discounts are offered. Therefore, the results suggest that price discounts are less effective in gift choice when social, rather than economic value, is salient.

Study 2

Study 1 show that when social, rather than economic, value is salient consumers are willing to purchase a non-discounted gift. It is then expected that consumers should not be concerned with discounts when purchasing gifts for others. However, in real purchase conditions today, consumers still embrace discounts during gift-giving holidays. The purpose of study 2 is to examine why and when are discounts persuasive in gift choice.

As stated earlier, gift shopping is more intense when the gift-giver needs to guess what the best gift would be for the recipient. The gift-giver has to consider many factors and the evaluation process can be cognitively and physically consuming. Research shows that when consumers face complex decisions consumers rely on heuristics, rules of thumb, hunch, gut feeling, or instinct (e.g., Chaiken & Trope, 1999; Evans, 1984). Also, research shows that such heuristics are often times found in the purchase environment (e.g., Evans 1984; Payne et al., 1993). Hence, the current study proposes that consumers will be influenced by environmental cues when purchasing gifts, especially when the overall value of a gift (i.e., monetary, social, appropriateness) is difficult to assess.

Interestingly, this paper also contends that environmental cues can make either economic or social value salient and affect consumers ‘choice accordingly. For simplicity, this paper refers to environmental cues that elicit social or economic value as social or economic cues, respectively. Social cues increase the perceived social value of the gift, for example, a third person’s positive opinion about the gift, indication of gift appropriateness (e.g., registry), information about how people that share similar characteristics to the recipient rate the gift (e.g., online reviews), among others. Economic cues increase the economic value of the gift, for example, price discounts, warranties, extended-service contracts, bundles, coupons, among others.

Hence, the current paper proposes that consumers’ assessment of the overall value of a gift is affected by the interplay between social and economic cues available to the consumer. Specifically, this paper contends that when social cues are not available to the consumer, economic cues will guide gift choice. In this case, consumers will become price conscious, and will be affected by price discounts. However, when social cues are available, purchase intention for an item will not depend on whether price discounts are offered. Given the social function of gift-giving, when consumers encounter social cues, consumers will prioritize social value and sacrifice economic value; even when economic cues are also present. In this case, consumers will be less price conscious, and as a consequence, less affected by price discounts. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3: When social cues are not available, purchase intention for an item will be higher when an economic cue is available compared to when an economic cue is not available.

H4: When social cues are available, purchase intention for an item will not depend on whether economic cues are available.

To test these hypotheses a 2 (social cue: yes, no) × 2 (economic cue: yes, no) between-subjects experimental design was conducted.

Participants and Procedures

One hundred and fifty undergraduate students in a large university in the Southern United States participated in the study in exchange for extra course credit. The study was conducted in a controlled lab setting. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four possible conditions. After evaluating the scenario, participants answered a questionnaire containing the measure of the dependent variable used in Study 1 (α = 0.93) and demographics.

The context of the experiment consisted of a shopping scenario for a wedding gift. Participants had to evaluate a wedding basket. The basket was chosen from a wedding gift website. The social cue scenario stated that the basket was part of a wedding registry. This information reduces the ambiguity about the appropriateness of the gift and increases its expected social value. In the no social cue condition, the scenario stated that the basket was one of many items available while gift shopping. Hence, the potential social value of the basket is unclear. In the economic cue scenario, participants were told that the gift was discounted by 50%. In the no economic cue, the scenario stated that the basket was offered at regular price. In all the scenarios, price information was omitted to avoid confounding effects due to participants’ socio-economic status. Instead, the scenario stated that the basket was within the budget.

Hypothesis Testing

A total of 124 responses were included in the analysis; 26 cases were excluded due to severe missing data or because they responded to filter questions (DiLalla & Dollinger, 2006). Cell sizes ranged from 26 to 34. Table 3 summarizes the results across cell conditions.

| Table 3: Cell Sizes And Mean Difference Across Conditions In Study 2 | |||

| No social cue | Without Economic cue | With Economic cue | With vs. Without Economic cue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Size | 31 | 26 | |

| Mean | 4.96 | 5.95 | p = 0.006 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.76 | 1.40 | |

| Social cue | |||

| Cell Size | 34 | 33 | |

| Mean | 5.99 | 6.29 | |

| Standard Deviation | 1.00 | 1.14 | p > 0.3 |

| With vs. Without Social cue | p = 0.002 | p > 0.3 | |

H3 stated that in when social cues are not available, purchase intention should be higher when economic cues are provided (discount) compared to when economic cues are not provided (no discount). H4 posited that when social cues are available, purchase intention should not differ across economic cue conditions. To test these hypotheses a two-way ANOVA was run with purchase intention as the dependent variable, and social cue and economic cue as the independent variables.

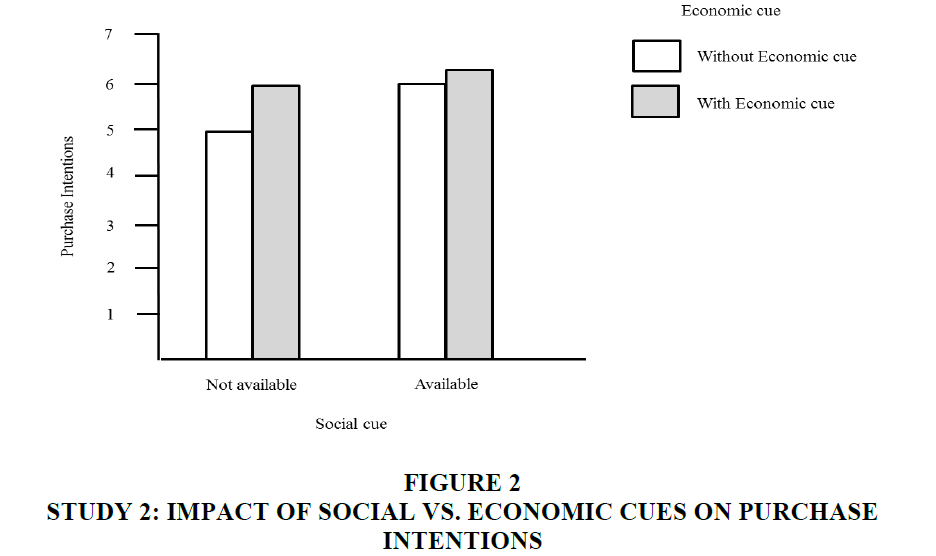

The results show that there was not a significant interaction effect (F (1,120) = 2.01, p = 0.16). The main effects of social (F (1,120) = 8.04, p < 0.01) and economic cues (F (1,120) = 7.10, p < 0.01) were significant. Pairwise comparisons were used to test the hypotheses and compare the effect of the economic cue (discount) in each social cue condition. The results of the pairwise comparisons showed that when social cues were not available, there was a significant difference between the no economic cue and economic cue condition. Specifically, purchase intention was higher in the discount (M = 5.95) condition than in the no discount (M = 4.96) condition (F (1, 120) = 7.69, p < 0.01). Thus, H3 was supported. In addition, the results showed that when a social cue was available, purchase intention was not significantly different between the no economic cue (M = 5.99) and the economic cue (M = 6.29) conditions (F (1, 120) = 0.849, p = .36). Hence, H4 was also supported. Furthermore, the results showed that in the no economic cue (no discount) condition, purchase intention was significantly higher when a social cue was available (M = 5.99) than when a social cue was not available (M = 4.96; F (1, 120) = 9.57, p < 0.01). Figure 2 depicts the findings.

Results of Study 2

The results of Study 2 showed that consumers’ purchase intention for a gift was more affected by an economic cue (i.e., a price discount) when social cues were not available than when social cues were available. This finding suggests that price discounts help consumers choose gifts when the social value of a gift is difficult to assess. However, a price discount is less effective in increasing purchase intention when consumers can assess the social value of a gift.

Overall Discussion

The objective of this investigation was to better understand the impact of price discounts on gift choice. The results of two lab experiments show that price discounts increase purchase intention for a gift when the economic value of the transaction is salient. However, the results also show that social, rather than economic; value is the priority in gift choice. This also supports the past studies that discounted items can increase perceived transaction value when the purchase is necessary, e.g., when the purchase is demanded by social relationships (Cai et al., 2015). Consequently, when the social value of a gift is salient, price discounts have a lesser impact on purchase intention. Furthermore, the results show that consumers’ perception of social and economic value is affected by environmental cues. Importantly, when social cues are not available, the social value of a gift is difficult to assess. In such situations, economic cues guide gift purchase decisions.

These findings explain why if social value is a priority in gift choice, consumers are often seduced by price discounts during gift-giving holidays such as Christmas and Valentine’s Day. First, during gift-giving holidays, the act of gift-giving is typically more important than the social value of the actual gift (Anton et al., 2013). Thus, in such situations social cues such as the appropriateness of the gift become less relevant and consumers will rely on economic cues. Second, even when consumers are searching for gifts that provide social value (e.g., a wedding gift), if consumers find it difficult to assess social value, consumers are likely to use economic cues as the decision criterion. Lastly, the results suggest that price discounts are seductive when consumers need to “guess” what a good gift would be for the recipient. When the gift-giver is unsure about the social value of a gift, the gift-giver will be seduced by price discounts. Overall, the findings suggest that a price discount is an environmental heuristic that helps consumers choose gifts when the social value of the gift is irrelevant or difficult to assess.

In addition, the research findings can explain the inefficiency of gift-giving. Gift-giving is inefficient when the gift does not generate social value (Larsen & Watson, 2001). Many people give gifts that are not appropriate or do not meet the recipient’s preferences (Camerer, 1988). People fail to choose the “right” gift because gift-giving is a guessing game. Consumers rely on environmental cues to guess the overall value of a gift. In absence of social cues, consumers will choose a gift based on economic cues. This pattern is likely to exacerbate during gift-giving holidays when gift-givers attempt to surprise recipients or when they want to purchase a gift to conform to social conventions. The popularity of price discounts during holiday seasons supports this idea.

Conclusion

Importantly, the findings suggest that it is in the best interest of business managers to help consumers choose the “right” gift. The gift that maximizes social value. Given the technological advances available in today’s marketplace, businesses should invest in systems that help consumers assess the appropriateness of a gift based on the recipient’s preferences, the occasion, and social conventions. For example, companies should create social network profiles for a customer’s network. Network profiles can inform customers about their friends’ preferences based on their past purchase behavior. By so doing, a win-win situation can emerge. On the one hand, customers will choose gifts that are more likely to generate social value. On the other hand, companies will provide social cues, make social value salient, and elicit a higher willingness to pay from customers. By emphasizing social cues, consumers will be less price conscious and less dependent on economic cues, such as price discounts.

In addition, the findings indicate that gift registries can be a satisfactory solution for people who are tired of putting efforts into selecting thoughtful gifts for friends. Gift registries also benefit business as consumers are less concerned with price discounts. Thus, registries should be used not only for traditional weddings, but also for other important events such as birthdays, graduations, anniversaries, and so on.

A limitation of helping consumers choose gifts, however, could be that the shopping experience is affected. Sometimes the effort put into shopping for a gift is more valuable than the gift itself (Camerer, 1988). Similarly, at times, consumers enjoy surprising recipients with unusual gifts. Thus, managers should find ways to provide social cues without harming the shopping experience. Future studies could test the interplay between social value (e.g., finding an appropriate gift), and the shopping experience.

References

- Anton, C., Camarero, C., & Gil, F. (2013). The culture of gift giving: what do consumers expect from commercial and personal contexts? Journal of Consumer Behavior, 13(1), 31-41.

- Belk, R.W., & Coon, G.S. (1993). Gift giving as agapic love: An alternative to the exchange paradigm based on dating experiences, Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 393-417.

- Blattberg, R.C., & Neslin, S.A. (1990). Sales Promotion: Concepts, Methods and Strategies, Prentice Hall, Engle wood Cliffs, New Jersey.

- Cai, F., Bagchi, R., & Gauri, D.K. (2015). Boomerang effects of low price discounts: how low price discounts affect purchase propensity. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(5), 804-816.

- Camerer, C. (1988). Gifts as economic signals and social symbols, American Journal of Sociology. 94, 180-214.

- Chaiken, S., & Trope, Y. (1999). Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology. Guilford, New York.

- Chang, T.Z., & Wildt, A.R. (1994). Price, product information, and purchase intention: an empirical study, Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 22(1), 16-27.

- DiLalla, D.L. & Dollinger, S.J. (2006). Cleaning up data and running preliminary analyses, in Leong, F.T.L. and J.T. Austin (Eds), The Psychology Research Handbook, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, 241-253.

- Dodds, W.B., & Monroe, K.B. (1985). The effect of brand and price information on subjective product evaluations, Advances in Consumer Research, 12, 85-90.

- Evans, J.S.B.T. (1984). Heuristic and analytic processes in reasoning, British Journal of Psychology, 75(4), 451-468.

- Ghajar-Khosravi, S., Holub, L., Canella, D., Sharpe, W., & Chignell, M. (2013). Simplifying the task of group gift giving. In The Personal Web, 185-220. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Goodwin, C., Smith, K.L., & Spiggle, S. (1990). Gift giving: consumer motivation and the gift purchase process, Advances in Consumer Research, 17, 690-698.

- Grewal, D., Krishnan, R., Baker, J., & Borin, N. (1998). The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers' evaluations and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74(3), 331-352.

- HellowWorld. (2019). 2019 Loyalty Barometer Report. Retrieved from https://helloworld.com/whitepaper/2019-loyalty-barometer-report

- Larsen, D., & Watson, J.J. (2001). A guide map to the terrain of gift value, Psychology & Marketing, 18(8), 889-906.

- Miller, R., & Washington, K. (2014). Consumer Behavior: Research Handbook Series. Richard Miller and Associates, Loganville, Georgia.

- Otnes, C.C., Lowrey, T.M., & Kim Y.C. (1993). Gift selection for easy and difficult recipients: a social roles interpretation, Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 229-244.

- Payne, J.W., Bettman, J.R., & Johnson, E.J., (1993). The adaptive decision maker. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Ruth, J.A., Otnes, C.C., & Brunel, F.F. (1999). Gift receipt and the reformulation of interpersonal relationships, Journal of Consumer Research, 25(4), 485-502.

- Solomon, M.R. (2012). Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having and Being, 10th edition. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

- Steffel, A., & LeBoeuf, R.A. (2014). Over individuation in gift giving: shopping for multiple recipients leads givers to choose unique but less preferred gifts, Journal of Consumer Research, 40(6), 1167-1180.

- Yi, Y. (1990). Cognitive and Affective Priming Effects of the Context for Print Advertisements, Journal of Advertising, 19(2), 40-48.