Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Policy Implementation of Forest Fire Handling and Treatment in the Perspective of the Government of Indonesia and Malaysia

Sholih Muadi, Brawijaya University

Keywords

Implementation, Policy, Prevention, Fire, Forest

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to describe and analyze the implementation of forest fire management and control policies in the perspective of the Indonesian and Malaysian governments. The research method used a qualitative approach, data analysis This study used a qualitative approach. The results showed the Dilemmas and Challenges of Haze Handling in Border Areas (1). It is traced to procedural norms and behavior embedded in the doctrine called the ASEAN Way which its members uphold. One such norm is the principle of enforcement of non-intervention and mutual respect. at the ASEAN level to combat environmental pollution has been deepened, with the introduction of various cooperative measures and projects, including haze mitigation initiatives (2). Indonesian Government Policy Approach in Haze Disaster Management in Perbatasana Area. (A) Diplomacy Steps. First track diplomacy in the form of bilateral diplomacy has been carried out by the Government of Indonesia and the Government of Malaysia since 1985. The Ministry of Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia, clarified that the Memorendum of Understanding (MoU) contains provisions for land clearing without burning (zero burning). Second track diplomacy between Indonesia and Malaysia on the issue of haze in Indonesia has been carried out since 1998 by several non-governmental organizations such as: Greenpeace, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), World Wide Fund (WWF) Indonesia. World Wind Fund dor Nature (WWF) Malaysia and the Global Environment Center (GEC). The non-governmental organization assists the first track diplomacy in realizing negotiations, in the form of preventing, providing information on the causes, impacts, losses of the haze, conducting technical exercises, and scientific research on forest fires that can cause haze. (B) Steps Through Court Roads The resolution of forest and land fires has been mostly through civil court proceedings, where the state, represented by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), has filed a lawsuit. Of the many complaints, only a few have reached court proceedings and the results have been unsatisfactory, ranging from light sanctions decisions to acquittals. Not to mention that it takes a long and convoluted process as well as the energy-draining problem of witnesses and evidence. The provisions regarding forest fires/burning in the forestry law actually do not give adequate attention to fire control efforts, because the prohibition on burning forests contained in the forestry law can actually be countered for special purposes as long as it obtains permission from the authorized official. Until now, there has not been a single law that prohibits clearing land by burning forests. Although there are forest and land fire control centers in the regions, but because of the missing legal instruments, it does not function optimally. (C) Completion through Forest, Garden and Land Fire Prevention Pilot Project (Ministry of Economic Affairs) The concept of this project focuses on early warning, early detection, early suppression, and center assistance. This pilot project will be carried out in villages bordering forest and plantation concessions of stakeholders who are committed to participating in the development of forest, land and plantation fire prevention.Through this pilot project, the government can formulate a concept of best practices and a well-tested standard operating procedure (SOP) for fire prevention which can be effectively applied across villages throughout Indonesia. (3) Malaysian Approach to Combating and Managing TransboundaryHaze Pollution Most of these actions are in the form of policy and legal reforms, with a focus on regulating and eliminating sources of environmental pollution, including haze. In addition, over the years, the Malaysian government's approach to the haze problem evolved into a multi-pronged strategy involving all federal and state agencies. Therefore, in cooperation with the Indonesian and provincial governments, it is in the interest of Malaysia to play an important role in preventing the widespread incidents of open burning on these plantations which are a major contributor to the haze. The following discussion will describe the policy and legal initiatives undertaken by Malaysia on the issue of transboundary haze.

Introduction

ndonesia itself since 2001 has had a set of regulations related to disaster management, such as Presidential Regulation No. 3 of 2001 concerning the National Coordinating Agency for Disaster Management and Refugee Management as amended by Presidential Decree No. 111 of 2001. In 2005 this policy was enhanced through the replacement of the Presidential Decree with Government Regulation (PP) no. 85 of 2005 concerning the Disaster Management Coordination Agency. However, the two regulations have not been able to become an umbrella that provides legal certainty. In addition, this regulation only focuses on establishing an agency to carry out emergency response tasks, meaning that it focuses on the aftermath of a disaster and there is no countermeasures aspect.The high incidence of disasters that have occurred during a period of 2 (two) years in Indonesia makes it necessary to pay more attention to disaster management in Indonesia.

Seeing this, the government on April 26 2007 issued Law no. 24 of 2007 concerning Disaster Management. This law was welcomed and became a separate history for the Indonesian nation. However, of course this law is not yet perfect because it still leaves problems in the aspects of substance and implementation. Several problems occur in terms that are not in accordance with international standards, besides that society is still placed on the object, not the subject.In the implementation aspect, there are symptoms that the government's commitment to implementing the existing substances is not serious enough. From a policy perspective, the model used for the formulation of the Law on Disaster Management is a combination of group and incremental models.

Political Aspects of Disaster Policy Research

The development of modern life allows research concepts and policies to be accommodated in a harmonious atmosphere. The very complex growth rate has had two effects at once, positive and negative. Policymakers, especially those who sit in government agencies, face an increasingly broad and multi-character task (Israel, 1992). It is impossible for the policy makers to manage the breadth and complexity of the tasks, both in terms of planning, implementing, evaluating, and controlling (Danim, 2000: 4).Policy formulation is no longer dominated by a few political elites who cannot be criticized, but now it has involved a growing number of citizens and interest groups. Thus the government is faced with increasingly diverse demands. As a result, today's citizens are increasingly concerned about public policies that directly affect their personal lives, so that the government must be more responsive and accommodating (Winarno, 2014).

Citizen participation theory is based on high expectations about the quality of citizens and their desire to be involved in public life. According to this theory, it takes citizens who have personality structures that are in accordance with democratic values and functions. Every citizen must have sufficient freedom to participate in political matters, have a healthy critical attitude and sufficient self-respect, more importantly a feeling of being capable. Above all, citizens must be interested in politics and become meaningfully involved (Koenig, 1986) in (Winarno, 2014). From the above understanding, we draw on Indonesia as a country with the potential for disaster, given that Indonesia is located between active mountains, plates and oceans, all of which are very prone to shifting or evolving. Indonesia is identified as a country with a very high potential for natural disasters. Such disasters can affect the national economy, welfare, and state politics, resulting in demands from the community to encourage the government to pay attention to aspects of disaster management through legal instruments.

The Indonesian government itself has established and enacted Law Number 24 of 2007 concerning Disaster Management (Law Number 24 of 2007), since 26 April 2007. This law has become the main source of law for disaster management, which is then followed up with implementing regulations., among others, Government Regulation Number 21 of 2008 concerning Disaster Management (PP No. 21 of 2008), Government Regulation Number 22 of 2008 concerning Disaster Aid Funding and Management (PP No. 22 of 2008), Government Regulation Number 23 of 2008 concerning Participation of International Institutions and Foreign Non-Government Organizations in Disaster Management (PP No. 23 of 2008), and Presidential Regulation No. 8 of 2008 concerning the National Disaster Management Agency (Presidential Decree No. 8 of 2008). However, there are still several problems in disaster management that have been included in the legislation. So that it requires several improvements in its implementation. Disaster management policies in Indonesia have not been implemented comprehensively, nor are they in accordance with disaster management in the international world and the legal needs of the community.

Public policy comes with a specific purpose, namely to regulate life together. From here we can put "public policy" as "management of achieving national goals". While it can be concluded that (Dwidjowijoto, 2003):

1. Public policy is easy to understand, because it means “things that are done to achieve national goals.

2. Public policy is easy to measure because the measure is clear, namely the extent to which progress has been made in achieving the goals.

However, this does not mean that public policies are easy to make, easy to implement, and easy to control, because public policies involve political factors. Politics is the art of possibility or the art of making the impossible possible.

Indonesia-Malaysia Transnational Disaster Policy

O'Brien, et al., (2000) in (Dwidjowijoto, 2003) argue that today, it is no longer sufficient to put good governance in a national context, but also in a global context, considering that today a number of multinational institutions have participated in and participate, even take an important role in global management.

Thus the public sector in the era of globalization extends not only at the national level, but includes regional and global levels because today the political policies of a country are increasingly influenced by decisions made by these global institutions. In fact, in some cases a country's public policies are cut off by these global institutions (Winarno, 2003).

Finally, it needs to be realized that public policies in every country, especially developing countries, must be placed at the global level (Dwidjowijoto, 2007). Public policy in developing countries is currently in the range of neo-institutionalism and the welfare state, with the latest developments tending to be neo-institutionalism. This current also occurred in Indonesia, particularly in decentralization policies and policies in autonomous regions where decentralization was implemented (Dwidjowijoto, 2007).

The disaster policies carried out between Indonesia and Malaysia cannot be separated from the various similarities that occur between the two countries. Indonesia and Malaysia are allied countries that have a tropical climate, with the majority of the same religion, namely Islam. Indonesia and Malaysia are both developing countries and are also members of ASEAN (Asia South East Asia Nation). In relation to the climate, the two countries are tropical countries that are traversed by the equator with the same natural character, so Indonesia and Malaysia have levels of disasters that are not much different. Although geopolitically, it is certainly different. The cooperation that will be carried out will not only produce good results for both parties, but can also provide benefits for the Southeast Asia region and also ASEAN.

Haze Pollution at the Border Disaster Management Policy

Trans boundary haze pollution is smoke haze pollution from a country whose effects reach another country, usually it is difficult to distinguish where the source is. The impact caused by this haze includes a security threat, where the security threats included are resource and environmental problems which reduce the quality of life and result in increased tension and tension among groups of countries. The annual haze generated by the burning of forests and land in Indonesia results in pollution that crosses national borders. On the one hand, for Indonesia, this incident was caused more by natural and cultural factors of the community, which resulted in losses to the ecosystem around the burning forest area. The haze that often blankets the Southeast Asia region comes from the burning of forests in Sumatra and Kalimantan. Since the forest fires and haze in Southeast Asia, countries in the region have created consultation groups to improve their management effectiveness.

Two years ago Malaysians felt the smog from forest and land fires in Sumatra firsthand, so Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak demanded that Indonesia take the matter seriously. Indonesia's reaction at that time, as stated by President Joko Widodo, was that it was "a problem that cannot be resolved quickly". President Jokowi then believes that the haze problem will decrease along with the improvement in handling and law enforcement aspects. Two years later, still related to the haze, on the sidelines of the 12th annual Indonesia-Malaysia consultation in Luching, Malaysia, Wednesday (22/11), Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak expressed gratitude to President Joko Widodo. "I thank the kingdom (government) of the Indonesian republic. "It has been two years that Malaysia has not experienced a rheumatic problem," said Najib. Jerebu is Malay for haze (BBC, 2017).

In the beginning, forest fires that caused haze were a domestic problem faced by Indonesia. However, forest fires that regularly occur in Sumatra and Kalimantan are long and intense, causing the smoke from the forest fires to cross the country's territorial borders.

1997-1998 was the initial period of the massive forest fire disaster. This is because the high level of El Nino climate continues to hit Indonesia in that year, resulting in large numbers of forest fires in several regions in Indonesia, including Kalimantan, Sumatra, Java, Sulasesi, Irian Jaya. Based on calculations in early 1998, Indonesia has lost 10 million hectares of its forest area. The 1997 forest fires were named one of the worst of all time. During this tragic event nearly 11 million hectares of land were burned for new crops with smoke and haze extending to Malaysia, Brunei, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines (Hidayatullah.com, 2019). Malaysia also played a part in causing fires in Indonesia. In the forest fires that occurred in Riau recently, approximately 8 (eight) Malaysian-owned companies were suspected of being involved in burning forests and land. The eight Malaysian investor companies that contributed to the smoke were PT. Multi Peat Industry, PT. UdayaLohDinawi, PT. Adei Plantation, PT. Jatim Jaya Perkasa, PT. Mustika Agro Lestari, PT. BmireksaSejati, PT. Tunggal Mitra Plantation, PT. The core style of Hiberida. One of the eight companies was declared involved, namely PT Adei Plantation (UMY, 2016).

Problem Formulation

Indonesia as a country prone to disasters has the political will (political will) to cope with the disasters that occur. This political will has been translated into legislation through a process of formulating a policy (legal policy) as part of the country's legal politics. This shows a correlation between legal politics and disaster management. Based on this, the study in this paper uses a framework related to disaster and legal norms.

Based on the background described above, the formulation of the problem in this research is: "How is the Implementation of Policies in Transnational Disaster Management between Indonesia and Malaysia to Overcome the Problems of Haze Disaster?"

The purpose

Of this research will be carried out by involving the two countries, namely Indonesia and Malaysia, where as the representative of Indonesia is from the Political Science Study Program of FISIB Universitas Brawijaya and as the representative of Malaysia is from SoIS (School of International Studies), Collage of Law, Government and International Studies. (COLGIS) Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM). So the goal is to formulate policies in cross-border disaster management between Indonesia and Malaysia in overcoming the problems of haze disaster based on existing laws and regulations.

Research Method

Research Approach

This research uses a qualitative approach. Qualitative research is interpretive research, in which the researcher engages in ongoing and ongoing experiences with participants. This involvement will lead to a series of strategic, ethical, and personal problems in the qualitative research process (Locke, Spirduso & Silverman, 2007) in (Creswell, 2017: 251).

In qualitative research, there will be three possibilities for facing problems, namely regarding the evaluation of policies in handling haze disaster at national borders. The first "problem" brought by the researcher remains, so that from the beginning to the end of the study the same. The second is the "problem" that is brought up, after entering the research, it can develop, that is, expanding or deepening the problem that has been prepared. Third, the "problems" that were brought, after entering the field changed completely, so that they had to "replace" the problem. Thus the title of the proposal with the research title is not the same and the title is changed.

Qualitative researchers who change the problem or change the title of their research after entering the research field or after completion, are better qualitative researchers, because researchers are able to let go of what they have thought before, and then are able to see phenomena more broadly and deeply in accordance with what is happening and develop in the social situation under study.

Location Settings

Qualitative research tends to collect field data in locations where participants experience the issue or problem to be studied. In this case, the natural setting is the individual from whom information is collected without prior setting. This means that researchers do not share instruments with them. The information collected is by talking directly to people and seeing them behave in a natural context which is the main characteristic of qualitative research. In a natural environment, qualitative researchers conducted face to face interactions throughout the study.

This location determination will be determined in Jakarta, Kalimantan and Sumatra and in Kedah Malaysia. This designation takes into account that Jakarta is the decision-making government, while Kalimantan and Sumatra are areas that are considered to be the ones that produce haze in Indonesia, and Kedah Malaysia is a very close border with Indonesia and was also involved in this research.

In connection with the location setting, literature study is carried out to obtain valid data, then the data is taken from the journal library.

Research Focus

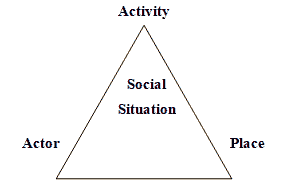

The research focus determined by the researcher is based on the overall social situation studied, which includes 3 (three aspects):

1. The aspect of place (place)

2. Actors (Actor)

3. Activity (Activity)

The three interact synergistically, if described as follows:

Spradley in Sanapiah Faisal (1988) suggests four alternatives for setting focus, namely (Sugiyono, 2014):

1. Establish focus on the problems suggested by the informant.

2. Define focus based on specific domains organizing domains.

3. establish a focus that has findings value for science and technology development.

4. Establishing focus based on problems related to existing theories.

So that in this research on Policy Implementation in Cross-Country Disaster Management between Indonesia and Malaysia to Overcome the Problems of Haze Disaster, the focus of the research can be divided as follows:

Research Focus Policy Implementation

Resource support in policy evaluation/analysis, Cross-sectoral involvement in haze prevention and mitigation, Efforts to involve academics, the public and the private sector in overcoming the haze, Forms of punishment for violators of rules that can cause haze disasters.

Research Instruments and Informant Selection

The main research instrument in qualitative research is the researcher himself. Researcher as a key instrument (resercher as a key instrument). Researchers collect their own data through documentation, behavioral observation, or interviews with participants. They may use protocols - some kind of instrument to collect data - but they are actually the only instruments in gathering information. They do not generally use questionnaires or instruments made by other researchers (Creswell, 2017).

The meaning of participants' meaning in the overall qualitative research process, researchers continue to focus on efforts to study the meaning conveyed by participants about a research problem or issue, not the meaning conveyed by other researchers or authors in certain literatures (Creswell, 2017).

The determination of informants in qualitative research is carried out using the triangulation method, meaning that the researcher will cross check the data that has been collected between the informants. The information in this research is: 1 Head of Public Relations BNPB (National Disaster Management Agency), 2. BNPB Disaster Response Sector. 3. IABI Central Management (Indonesian Association of Disaster Experts). 4. Members of the Indonesian House of Representatives, Commission VIII in charge of Disaster Affairs and the Ministry of Forestry.

Data Collection

Researchers in most qualitative studies collect various types of data and use the most time as effectively as possible to gather information at the research location (Creswell, 2017).

Data Analysis and Data Interpretation

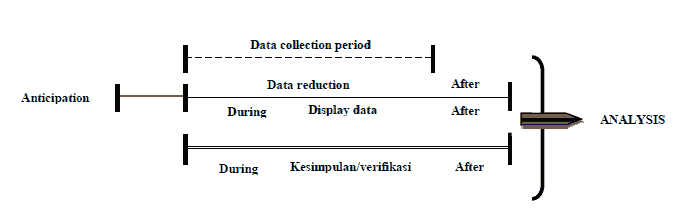

Data analysis in qualitative research will take place simultaneously with other parts of qualitative research development, namely data collection and writing findings. When the interviews are collected beforehand, write down a memo which is eventually included as narrative in the final report, and structure the final report. This process is unlike quantitative research where the researcher collects data, then analyzes the information, and finally writes a report. Miles-Huberman describes data analysis and reduction for qualitative research as follows:

Techniques to Ensure Data Validity

Although the validation of research results can take place during the research process, the researcher still has to focus his discussion on this validation by writing validation procedures in a special section of the proposal. Researchers need to convey the steps taken to check the accuracy and credibility of their research results.

In qualitative research, this validity does not have the same connotations as validity in quantitative research, nor is it parallel to reliability (which means stability testing) or generalisability (which means external validity of research results that can be applied to new settings, people or samples. in quantitative research).

Qualitative validity is an effort to check the accuracy of research results by applying certain procedures, while qualitative reliability indicates that the approach used by researchers is consistent when applied by other researchers (and) to different projects (Gibbs, 2007).

Results and Discussion

Results

Territorial Border between Indonesia and Malaysia

The border between Indonesia and Malaysia stretches along 2,019 km from TanjungBatu, North West Kalimantan. Passing through the inland highlands of Kalimantan, to the TelukSebatik and Latu Sulawesi in the east of Kalimantan. The maritime borders in the Malacca Strait are generally determined based on the median line between the bases of the continents of Indonesia and Malaysia, stretching south from the Malaysia-Thailand border to the meeting point of the Malaysia-Singapore border (https://id.m.wikipedia.org)

The RI-Malaysia border is one of the border areas that has an important and strategic position in the context of national development. As the gateway to the Republic of Indonesia, the borders of the two countries include maritime borders along the Malacca Strait, South China Sea and Sulawesi Sea, as well as the land border that separates the two countries on the island of Kalimantan along 2004 km. This is the longest physical border in Indonesia with other countries, which stretches across the Provinces of West Kalimantan, East Kalimantan Province and North Kalimantan Province. The three provinces are directly bordered by land to the Malaysian state, namely Sarawak and Sabah.

The RI-Malaysia border area which is currently recognized is essentially a colonial product. In this case, the struggle for territory between the Dutch and British in Kalimantan resulted in the agreements contained in the three Treaties, namely the Treaty of The Boundary Convention between the Netherlands and England signed in London, 20 June 1891, The Boundary Agreement between the Netherlands and England signed in London, September 28, 1915, and The Boundary Convention between the Netherlands and England signed in the Hague, March 26, 1928 (Ihsan, 2019).

As a colonial product, Indonesia and Malaysia, which each inherited the Dutch and British agreement on the division of sovereign territory at the border of the two countries, still inherit the problem of territorial division which has not been resolved. A number of issues related to the determination of maritime and land boundaries between RI and Malaysia indicate this reality. One of the border disputes between the two countries is the determination of maritime boundaries between the two countries that have not been agreed upon by the two countries, mainly in three segments, namely the Malacca Strait segment, the South China Sea segment, and the Sulawesi Sea segment.5 The disputes in the three segments, among others, relate to the problem of territorial sea boundaries, the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the continental shelf and overlapping claims in waters, especially around the Ambalat Block. This overlap was a result of the decision of the International Court of Justice regarding the ownership of the Sipidan-Ligitan Island to the Malaysian government in 2002.6 As is the case in the maritime border area, Indonesia-Malaysia also still faces disputes in determining land borders. There are nine boundary points that have not been completely agreed upon by both parties, namely five points in the East Kalimantan area and four points in the West Kalimantan area (Directorate -23, 2013) in (Wengkey, 2018)

Border Map between Indonesia and Malaysia

Indonesia has a border zone with 10 (ten) neighboring countries in the waters and 3 (three) on the land border. In the sea area, Indonesia is directly adjacent to Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, India, Thailand, the Republic of Palau, Australia, Timor Leste and Papua New Guinea. Meanwhile on land territory, Indonesia is bordered by Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste and Malaysia. The definitive determination of state boundaries can provide clarity and legal certainty regarding the rights and obligations of the state in managing its territory. However, Indonesia still has several problems related to the settlement and confirmation of state boundaries with neighboring countries in several border areas. In the land border area, Indonesia and Malaysia have territorial disputes in 9 (nine) points in the land boundary zone of the East Sector of Kalimantan Island, which includes areas on Sebatik Island, Sinapad River, Simantipal River, Point B2700-B3100, C500-C600 in East Sector, as well as the BatuAum area, Buan River/Mount Jagoi, Gunung Raya and Point D400 in the West Sector. Based on the principle of UtiPossitedisJuris, both Indonesia and Malaysia should inherit areas previously controlled by the Dutch and British, which were their colonial states in the past. The regional agreements that have been agreed by the two countries include the Treaty between Great Britain and the Netherlands defining Boundaries in Borneo (1891), the Agreement Between Great Britain and the Netherlands relative to the Boundaries Between State of Borneo and the Dutch Possessions in Borneo (1915), and Treaty Respecting the Further Delimitation of the Frontier Between the State of Borneo Under British Protection and the Netherlands Territory in the Island (1928); (Ihsan, 2019).

These differences, among others, relate to the agreements in 1891 and 1915 in the East Sector, as well as the Treaty of 1928 in the West Sector of Kalimantan Island. The nine points of land boundary dispute areas which are commonly known as Outstanding Boundary Problems are also related to the implementation of the Survey Procedure which was carried out jointly in 1974. Both Indonesia and Malaysia have different views on the results of field measurements that are not in accordance with the agreed agreement, and feel disadvantaged by each other in different areas. This then became the reason for holding negotiations on the boundaries of the two countries. Until now, Indonesia and Malaysia have agreed to prioritize areas in the East Sector first, but the negotiation process has not been able to produce an agreement regarding the boundaries of the two countries. Since the 1970s, several Memorandums of Understanding (MoU) have been agreed, namely the MoU between Indonesia-Malaysia in Jakarta on 26 November 1973, Minutes of the First Meeting of the Joint Malaysia-Indonesia Boundary Committee on 16 November 1974, and the Minutes of the Second Meeting of the Joint Indonesia-Malaysia Boundary Committee in Bali, on July 7, 1975. The confirmation of the land boundaries between Indonesia and Malaysia was carried out in the form of a Joint Survey on Demarcation which began in 1975 and was declared completed in 2000 (Ihsan, 2019).

Handling carried out by the government in cases of forest and land fires is dominated by repressive handling, such as extinction and law enforcement. If we look at the causes of forest and land fires as stated above, the policies implemented so far have only been limited to overcoming the problem of land clearing by burning. Meanwhile, other causes such as land conversion, natural resource utilization activities, peat land use, land disputes have not been touched on in forest and land fire control policies.

Dilemmas and Challenges of Haze Handling in Border Areas

Within the boundaries of national jurisdiction, a country has absolute sovereignty and the power to enact and enforce relevant national laws or regulations for the purpose of reducing and preventing smog pollution. Such supreme powers are granted to individual States to carry out such acts provided under the framework of international law. Relevantly, each State has legal authority over individuals or entities within its territory. Therefore, applicable domestic laws or regulations may contain clauses to establish and prosecute any person or entity, including private companies, for committing an offense that causes or contributes to smoke haze pollution. To prevent individuals or entities from committing such offenses, States may impose stricter penalties in the case of substantial monetary fines or lengthy prison terms.

However, there are uncertainties, as well as difficulties in enforcing and enforcing domestic laws or regulations outside the boundaries of national jurisdictions. This is a definite case of the challenge of reducing and preventing transboundary haze in the Southeast Asian region. Due to the transboundary nature of the haze emanating from the Indonesian territory that envelops neighboring countries, with Singapore and Malaysia suffering the most dangerous impacts, it will be difficult and nearly impossible for the two affected States to extend their respective powers to apply domestic law in the country. foreigners, especially to capture and prosecute individuals or entities involved in causing the haze. Unless there is the signing of an extradition treaty, it is not the obligation for a State to hand over suspect offenders to the requested foreign State. An example of this legal challenge could point to the difficulties Singapore authorities may face when implementing the Transboundary Haze Pollution Act 2014, which contains clauses establishing extra-territorial effects. This law imposes extra-territorial responsibility for entities responsible for haze pollution overseas. The question arises whether the Indonesian government is willing to agree to this broad jurisdiction without compromising its sovereignty.

Perhaps, one of the challenges to addressing environmental problems such as trans boundary haze pollution in the region can be traced to procedural and behavioral norms embedded in the so-called ASEAN Way doctrine that its members adhere to. One of these norms is the principle of enforcement of non-intervention and mutual respect (Kivimaki, 2001). The practice of encroachment or interference into the domestic affairs of other sovereign countries in the region can be seen as taboo among ASEAN members. Therefore, the provision of financial or technical assistance to reduce or prevent environmental pollution, such as haze, can only be deemed acceptable with the consent of the receiving countries. Therefore, it is a challenge for each individual Stateto to effectively prevent recurring incidents without the permission or cooperation of the Indonesian government.

It appears that cooperation at the ASEAN level to combat environmental pollution has deepened, with the introduction of various cooperative measures and projects, including haze mitigation initiatives. However, many of these regional initiatives, as noted earlier, were ineffective and failed to achieve the desired results. ATHP is considered ineffective for reducing smog pollution in this region because of its status as a non-legally binding instrument (Heillman, 2016). Therefore, the implementation of the Agreement by Member States is voluntary. ATHP has sufficient autonomy and discretion to select and elect one of the provisions for implementation (Shukoret, 2018). This is further complicated by the absence of a centralized institution to compel parties to comply with Agreement clauses. it is for this reason that the Agreement lacks the credibility to be an effective instrument to reduce the haze problem in the region.

The Indonesian Government's Policy Approach in Haze Disaster Management in Border Areas

Forest and land fires in Indonesia are caused by many factors, including natural factors, human factors. One of the human factors is the act of foreign companies burning forests and land for plantation purposes. By burning forests and land, it saves more money to open new plantation land than renting tools to clear land.

As said by Dr. Laila Surya Ahmad Apandi (Lecturer in SoIS and Research in International Relations, Political Economy and Foreign Policy in an interview, that:

"The Indonesian government should make a stricter policy on the application of the law, so that it has a deterrent effect (law enforcement). This is not just a matter of enforcing the rules, but enforcing the law without discrimination. Here it is seen that the law is weak, so there are many holes in the law that can be entered, so that the elements can escape (not yet able to ensnare the main actors). " (Interview, August 8, 2019 at SoIS UUM).

The cross-border forest fires caused by the occurrence of forest and land fires in Indonesia, especially in Riau, have caused Malaysia a great loss because the haze has severely impacted the economy, tourism and health in Malaysia. But Indonesia and Malaysia realized that blaming each other on the forest fire problem would not be resolved. Therefore, the two countries began to collaborate to deal with this forest fire problem.

Diplomacy Steps

The problem of haze in Indonesia is not a new issue. This haze problem has occurred since 1982. However, the worst smoke haze occurred in Indonesia, namely in 1997. The problem of smog in Indonesia is caused by burning forests and land. The haze issue tends to cross the Malaysian border every year in 1997-present, so that Indonesia and Malaysia take diplomatic steps to resolve the issue.

On the issue of smog in Indonesia, firt track diplomacy in the form of bilateral diplomacy has been carried out by the Government of Indonesia and the Government of Malaysia since 1985. The diplomacy carried out includes conducting patrols in the air in response to the haze and warning the public not to move outside the home. Diplomacy between the two of them has developed, in the form of a bilateral agreement which resulted in an MoU on joint management of the haze problem.

The Ministry of Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia, clarified that the Memorendum of Understanding (MoU) contains provisions for land clearing without burning (zero burning), monitoring, prevention of prevention through sustainable peat land management (peat land management), extinction, development of early warning systems, law enforcement, increased cooperation in dealing with haze in fire prone areas, preparing volunteer firefighters and medical personnel. Furthermore, the diplomacy carried out includes improving training for communities around the forest by clearing land without burning (zero burning), increasing volunteer firefighters and medical personnel.

Meanwhile, the second track of Indonesian and Malaysian diplomacy on the issue of haze in Indonesia has been carried out since 1998 by several non-governmental organizations such as: Greenpeace, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), World Wide Fund (WWF) Indonesia. World Wind Fund dor Nature (WWF) Malaysia and the Global Environment Center (GEC). The non-governmental organization assists the first track diplomacy in realizing negotiations, in the form of preventing, providing information on the causes, impacts, losses of the haze, conducting technical exercises, and scientific research on forest fires that can cause haze.

The collaboration between Indonesia and Malaysia which is carried out in Jakarta discusses several fields of activity that will be carried out, as for some of these activities, namely:

a. Fire Prevention (with a focus on outreach programs);

b. Capacity building for communities, farmers, plantation companies and concessionaires;

c. Pilot projects on no-combustion techniques;

d. Rehabilitation of damaged peatlands;

e. Early Warning and Monitoring;

Any other areas of cooperation in preventive measures to deal with land and forest fires and haze in Riau Province, Indonesia to be mutually agreed upon by the Parties.

There are several activities or programs that have been implemented, namely:

Zero Burning Technique Workshop Training for Community Leaders & Farmers from RokanHilir Regency, Riau Province, Sepang, Selangor. 27 participants from Indonesia attended the training session which was officiated by the Malaysian Minister of Natural Resources and Environment. Training based on open burning laws and law enforcement, zero burning techniques in agricultural practices and sustainable peat land management was delivered by experts from the Department of Environment, Department of Agriculture, Department of Drainage and Irrigation and the Global Environment Center (GEC). In addition, participants were brought to witness zero burning practices in agricultural agriculture at Taman Agrotek, Sepang, Selangor.

The no-burning technique is a method of clearing land where the standing of trees, either logged over secondary forests or old areas of plantation tree crops such as oil palm, are cut, shredded, stacked and left there to decompose naturally.

Advantages of the No Burn Technique:

– Environmentally friendly approach because it does not cause forest fires.

– Zero burning techniques reduce Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, particularly CO2.

– Through crop biomass recycling, no-burning techniques improve soil organic matter, water retention and soil fertility, especially in areas that have been planted with more than one generation of plantation crops. This reduces the overall need for inorganic fertilizers and minimizes the risk of water contamination through washing or washing the nutrient surface.

– The agronomic benefits can be increased if oil palm seedlings are planted directly into the residue pile instead of bare soil. through this approach, higher levels of total nitrogen, exchange of potassium, calcium and magnesium can be obtained and nutrients released over a longer period.

– Unlike land clearing by burning, the zero burning technique is less dependent on weather conditions.

– Zero burning technique has a short fallow period from clearing by burning; crops and legume covers can be planted within two months of felling and shredding; the latter provides faster coverage of the soil and minimizes soil loss and pollution through runoff.

– As the no-burning technique involves progressive logging, applying the replanting technique of oil palm will generate additional income from the continued harvest of the palms until they are cut down. Income can offset the additional costs incurred. Overall, the costs of implementing zero burning techniques for replanting oil palm with a new generation of palms are comparable to or cheaper than clearing land by burning.

– In the long term, an analysis of experience to date has shown that an approach that does not involve the use of fire and the removal of biomass will ensure economic and ecological sustainability.

Step through the Court Way

Settlement through appropriate means, namely through procedures, usually law enforcement by litigation or trial. Litigation has advantages, among others, a free and impartial judiciary, justice is carried out for the sake of justice based on the One Godhead and without discriminating against people. While the shortcomings take a long time and wordy. For example, if one party is dissatisfied with the judge's decision, then it can file an appeal and review at the Supreme Court level and the cost of the case borne by the parties is expensive (Aryo Mukti, 2001, page 7) in (Hunawan, 2016). This becomes a consideration for the parties when conducting litigation, especially if it continues to appeal.

Sometimes the law that is used as a reference by the judge is not in accordance with the social conditions and conditions. Because basically a law is always behind the conditions and conditions that occur in the society it regulates. In fact, every dispute is always related to non-legal technical matters, for example economic, social, political and other aspects. Courts tend to focus on technical normative legal issues by ignoring other substantive issues, so that the final settlement results are partial and win-lose will occur. Judicial decisions are considered not solving problems, understanding and not arguing for judges in plantation dispute issues, so the court decisions that are decided by the judges are considered not solving the problem and are considered not providing a sense of justice for parties who have problems.

The resolution of forest and land fires so far has mostly been through civil court proceedings, where the state, represented by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), has filed a lawsuit. Of the many complaints, only a few have reached court proceedings and the results have been unsatisfactory, ranging from light sanctions decisions to acquittals. Not to mention that it takes a long and convoluted process as well as the energy-draining problem of witnesses and evidence. There have been many regulations governing forest and land fire management, among others (Hunawan, 2016):

a. Law Number 23 of 1997

Law on Environmental Management. Regulates the obligation of each person to maintain the preservation of the environment and prevent and overcome environmental pollution and destruction. With a maximum imprisonment of 10 years and a maximum fine of Rp. 500 million, other than that, disciplinary actions can be imposed in the form of confiscation of profits, company closure, and repair of damage.

b. Law No. 41 1999

Law No. 41 1999 concerning Forestry Article 50 paragraph 3, forest burning is subject to a maximum imprisonment of 15 years and/or a maximum fine of IDR 15 billion. Article 78 paragraph 4 is subject to a maximum fine of 5 years imprisonment and/or a maximum fine of IDR 1.5 billion.

c. Government Regulation No. 4 of 2001

Government Regulation No. 4 of 2001 concerning Control of Environmental Damage and Pollution. In the PP, there is a prohibition against burning forests and land, it's just that the prohibition is only subject to administrative sanctions.

d. Article 10 paragraph (2) letter b, Government Regulation No.45 of 2004

Article 10 paragraph (2) letter b, Government Regulation No.45 of 2004 concerning Forest Protection stipulates that forest protection activities include prevention, extinguishing and handling of fire impacts. It's just that in articles 42 and 43 of the PP it is stated that the criminal action of the impact of forest fires is only applied to parties who do not have documents and permits for forest products.

e. Law No. 18 of 2004

Law No. 18 of 2004 on Plantation has the obligation to preserve environmental functions. With a maximum imprisonment of 3 years and a maximum fine of IDR 3 billion or both. The tools used.

f. Law Number 19 of 2004 concerning Forestry.

Law Number 19 of 2004 concerning Forestry Explain the principle of forest burning prohibited. Limited burning of forest is permitted only for special purposes or conditions that cannot be avoided, including controlling forest fires, eradicating pests and diseases, and fostering plant and animal habitats. Sanctions are in the form of a maximum threat of 15 years and a maximum fine of IDR 5 billion and negligence threatens to a maximum of 5 years imprisonment and a fine of IDR 1.5 billion or cumulative sanctions.

g. Law No.32 of 2009 concerning Environmental Management.

Law No.32 of 2009 concerning Environmental Management Article 69 clearly regulates related acts against the law committing an act that causes pollution and/or damage to the environment. In addition, this law also regulates criminal provisions for people who burn land.

The provisions regarding forest fires/burning in the forestry law actually do not give adequate attention to fire control efforts, because the prohibition on burning forests contained in the forestry law can actually be countered for special purposes as long as it obtains permission from the authorized official. Meanwhile the provisions in Government Regulation (PP) No. 4 of 2001 minimizes the interpretation of the use of article 10 in PP No.45 of 2004 concerning law enforcement actions, meaning that forest protection measures from forest protection measures from burning will be applied to those perpetrators who do not have permits or valid documents according to applicable regulations. Also in PP No. 4 of 2001, the provisions for sanctions for forest burning are only subject to administrative sanctions as stipulated in articles 25 and 27 of Law No. 23 of 1997 on environmental management.

On the other hand, Law No. 23/1997 on environmental management also does not provide a specific purpose for developing regulations under it (at the level of government regulations) regarding environmental pollution such as the case of forest fires. The same is the case with Law No. 18 of 2004 concerning plantations which does not contain administrative sanctions for companies conducting land clearing by burning. In fact, one of the things required by law enforcers is in accordance with the mandate of environmental (forest) conservation and the principle of zero burning which is stipulated in several international agreement (law) clauses. Meanwhile, on the other hand, to date there has not been a single law prohibiting land clearing by burning forests. Although there are forest and land fire control centers in the regions, but because of the missing legal instruments, it does not function optimally.

Discussion

Settlement through the Pilot Project for Prevention of Fire for Forests, Gardens and Land (Ministry of Economic Affairs)

This project concept focuses on early warning, early detection, early shutdown, and center assistance. This pilot project will be carried out in villages bordering forest and plantation concessions of stakeholders who are committed to participating in the development of forest, land and plantation fire prevention. Through this pilot project, the government can formulate a concept of best practices and a well-tested Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for fire prevention which can be effectively applied across villages throughout Indonesia.

Through interviews conducted with Mayjend. TNI (Ret.) Prof.Dr. SyamsulMaarif, M.Si (Head of BNPB 2008-2015, in Sentul Bogor), where it is said that:

"It needs to be seen more from the budget side, that in 2017-2018 the allocated funds amounted to 400 billion, plus the emergency response budget was several trillion, while at the time I took office the funds had already been budgeted 1.6 trillion, so prevention is much more important, because preventive action is much more important than emergency response, because what happens is high cost."

This project concept focuses on early warning, early detection, early shutdown, and center assistance. This pilot project will be carried out in villages bordering forest and plantation concessions of stakeholders who are committed to participating in the development of forest, land and plantation fire prevention. Through this pilot project, the government can formulate a concept of best practices and a well-tested Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for fire prevention which can be effectively applied across villages throughout Indonesia.

Through interviews conducted with Mayjend. TNI (Ret.) Prof.Dr. SyamsulMaarif, M.Si (Head of BNPB 2008-2015, in Sentul Bogor), where it is said that:

"It needs to be seen more from the budget side, that in 2017-2018 the allocated funds amounted to 400 billion, plus the emergency response budget was several trillion, while at the time I took office the funds had already been budgeted 1.6 trillion, so prevention is much more important, because preventive action is much more important than emergency response, because what happens is high cost."

a. Socialization for around 1700 in 22 elementary schools (SD), junior high schools (SMP) and senior high schools (SMA) in order to become agents of change in society.

b. Socializing the dangers of forest, land and garden fires for health, especially for groups of women, children and the elderly and providing direct guidance and training to villagers.

c. Dissemination of public messages through public advertisements in the regions.

d. Training villagers by taking 15 people from each village selected to become volunteers. All of these volunteers are trained and supported in conducting effective hotspot monitoring, as well as conveying information quickly to the response team, either by e-mail, short message (sms), telephone or other means of communication.

e. Fire fighting infrastructure assistance

f. Providing incentives (rewards) to the best villages that have succeeded in preventing and dealing with potential fires, in the form of additional social infrastructure development assistance or technical assistance.

g. Monitoring of locations and hotspots is also carried out using drone technology, unmanned aircraft, as well as a satellite-based hot spot monitoring system whose data processing results will be forwarded to the village task force post in its operational area.

h. Encourage community participation to map village boundaries and land in their territory as part of a fire prevention and management strategy.

i. Agricultural training on demonstration plots agreed by residents, use of environmentally friendly fertilizers, improved water management and so on as an alternative solution to agricultural practices without burning.

j. Provides more than 10 thousand emergency response personnel, more than 20 types of card fire fighting equipment and a number of medical personnel

Malaysian Approach in Combating and Managing Trans boundary Haze Pollution

Malaysia is one of the ASEAN countries that suffers the most from the devastating effects of trans boundary pollution emitted from Indonesian territory. Recurring episodes of fog pollution over the past thirty years have had a negative impact on the health, quality of life, and economic production of most Malaysians (Prettoet, 2015). In response to these repeated episodes of trans boundary haze pollution and the growing public concern over the haze episodes, the Malaysian government has taken a number of actions. Most of these actions are in the form of policy and legal reforms, with a focus on regulating and eliminating sources of environmental pollution, including haze. In addition, over the years, the Malaysian government's approach to the haze problem evolved into a multi-pronged strategy involving all federal and state agencies.

Considering that the cause of the haze in this region is mostly from Indonesian territory, the Malaysian government has initiated a number of projects and cooperation programs with its Indonesian counterparts. Such bilateral initiatives aim to reduce and prevent the recurrence of smoke haze pollution from the open burning of commercial oil palm plantations, particularly in Kalimantan. Understandably, Malaysia has a strong interest in the palm oil industry which is very profitable in Indonesia. According to Rahman (2013), as quoted in Ku Yusofet (2017), Malaysian and Singaporean companies own two-thirds of the total area of oil palm plantations in Indonesia, with a total investment of US $ 713.6 million. Therefore, in cooperation with the Indonesian and provincial governments, it is in the interest of Malaysia to play an important role in preventing the widespread incidents of open burning on these plantations which are a major contributor to the haze. The following discussion will describe the policy and legal initiatives undertaken by Malaysia on the issue of trans boundary haze.

Conclusions and Suggestions

Conclusion

Dilemmas and Challenges of Haze Handling in Border Areas.

1. It is traced to procedural norms and behavior embedded in the doctrine called the ASEAN Way which its members uphold. One such norm is the principle of enforcement of non-intervention and mutual respect. at the ASEAN level to combat environmental pollution has been deepened, with the introduction of various cooperative measures and projects, including haze mitigation initiatives.

a. Indonesian Government Policy Approach in Haze Disaster Management in Border Areas. Diplomacy Steps. First track diplomacy in the form of bilateral diplomacy has been carried out by the Government of Indonesia and the Government of Malaysia since 1985. The Ministry of Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia made clear that the Memorendum of Understanding (MoU) contains provisions for land clearing without burning (zero burning). The second track diplomacy of Indonesia and Malaysia on the issue of haze in Indonesia has been carried out since 1998 by several non-governmental organizations such as: Greenpeace, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), World Wide Fund (WWF) Indonesia. World Wind Fund dor Nature (WWF) Malaysia and the Global Environment Center (GEC). The non-governmental organization assists the first track diplomacy in realizing negotiations, in the form of preventing, providing information on the causes, impacts, losses of the haze, conducting technical exercises, and scientific research on forest fires that can cause haze.

b. Step Through the Way of Court. The resolution of forest and land fires so far has been mostly through civil court proceedings, where the state, represented by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), has filed a lawsuit. Of the many complaints, only a few have reached court proceedings and the results have been unsatisfactory, ranging from light sanctions decisions to acquittals. Not to mention that it takes a long and convoluted process as well as the energy-draining problem of witnesses and evidence. The provisions regarding forest fires/burning in the forestry law actually do not give adequate attention to fire control efforts, because the prohibition on burning forests contained in the forestry law can actually be countered for special purposes as long as it obtains permission from the authorized official. Until now, there has not been a single law that prohibits clearing land by burning forests. Although there are forest and land fire control centers in the regions, but because of the missing legal instruments, it does not function optimally.

c. Settlement through Forest, Plantation and Land Fire Prevention Pilot Project (Ministry of Economic Affairs). The concept of this project focuses on early warning, early detection, early shutdown, and center assistance. This pilot project will be conducted in villages bordering forest and plantation concessions of stakeholders who are committed to participating in the development of forest, land and plantation fire prevention. Through this pilot project, the government can formulate a concept of best practices and a well-tested Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for fire prevention which can be effectively applied across villages throughout Indonesia.

2. Malaysian Approach in Combating and Managing Transboundary Haze Pollution

Most of these actions are in the form of policy and legal reforms, with a focus on regulating and eliminating sources of environmental pollution, including haze. In addition, over the years, the Malaysian government's approach to the haze problem evolved into a multi-pronged strategy involving all federal and state agencies. Therefore, in cooperation with the Indonesian and provincial governments, it is in the interest of Malaysia to play an important role in preventing the widespread incidence of open burning activities on these plantations which are a major contributor to the haze. The following discussion will describe the policy and legal initiatives undertaken by Malaysia on the issue of transboundary haze.

Suggestion

1. Review the permits that have been granted for the development of oil palm plantations. This strategy is important to ensure that oil palm plantation development is not supposed to result in deforestation, peatland destruction and carbon emissions. A review was carried out on reforestation of forests (reforestation) of deforested forests (deforestation) due to land clearing which was carried out without replanting. And this permission must be strict.

2. Community awareness campaigns should be followed by empowerment, so that people have other livelihoods that do not destroy the forest. The community is given information about the dangers of reckless land clearing. Providing skills for the community not to depend entirely on their livelihoods which have to clear the forest as the main factor.

3. A review of overlapping forest and land use permits must be carried out immediately, especially on lands that overlap with the ulayat lands of indigenous peoples. Segregation must be carried out so that there is no friction in the community regarding land ownership.

References

- Andersen, E.J. (1997). Public policy-making, (Third Edition). New York: Holt Rinchart Winston.

- Bencana, B.N.P. (2018). RBI: Risiko Bencana Indonesia.

- Creswell, W. (2017). Research design: Approaches to qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Yogyakarta: Student Library.

- Dwijowodjoto, R.N. (2004). Public Policy: Formulation, Implementation, and Evaluation. Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo.

- Hunawan, D. (2016). Resolving Forest and Land Fires (KARHUTLA) in Indonesia through “Jalan Adas” or “Jalan Pintas” ? Journal of Unnes, 2(1), 277-292.

- Ihsan, Risky. (2019). Land boundary disputes and border diplomacy between indonesia and malaysia. Archived at: Retrieved: 25 July 2019

- Indiahono, D. (2009). Public policy: Based on dynamic policy analysis. Yogyakarta: Gava Media.

- National Board for Disaster Management. (2018). Disaster information national disaster management agency. Filed on. Retrieved date

- Kusumasari, B. (2015). Disaster management and local government capabilities. Yogyakarta: Gava Media.

- Said, M.F. (2010). Disobedience of weru fishermen to the policy to ban the use of trawl nets. Surabaya: Bimantara Aluugoda Sejahtera.

- Sugiyono. (2008). Understanding qualitative research. Bandung: Alfabeta.

- Winarno, B. (2014). Public policy: Theory, process and case studies. Yogyakarta: CAPS (Center of Academic of Publishing Service).