Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 4S

Perfume advertisements: A Cross-Cultural Study of the Visual Grammar Deployed

Mohammed Alhuthali, Taif University, Saudi Arabia

Citation Information: Alhuthali M., (2024). Perfume advertisements: a cross-cultural study of the visual grammar deployed. Journal of Organizational Culture Communications and Conflict, 28(S4), 1-14

Abstract

This paper considers the visual grammar of perfume adverts with the goal of understanding the semiotic modes used and whether these vary by culture (Saudi or non-Saudi) or by the gender of the target audience. Data was collected from on-line perfume adverts that contain a human figure. Since the goal was a detailed semiotic analysis of each only twelve images are used as the basis for this paper. While perfume advertising shares much with wider norms in advertising there is one key difference for adverts that rely on text and image. In effect, the smell of the product is they key aspect when it is used and is necessarily missing from any such advert. This tends the adverts towards some degree of ideation, in particular how the consumer will look if they use that particular fragrance. In this study this led to a conclusion that culture played little role in determining the semiotic resources used but the dominant vector was one of a demand from the model to the user.

Keywords

Visual Grammar, Ideation, Perfume Advertising, Vectors

Introduction

This study looks at a dozen adverts for perfumes. Half are produced by Saudi based companies (and of these the bulk were for the Saudi market) and the others by different global brands with an equally global reach. This design allows for comparison between adverts that may have a distinctive cultural framing (Abokhoza & Hamdalla, 2019) as opposed to those designed for a more varied audience. In addition, the sample includes a mix of fragrances for men and for women (Tuna & Simões, 2012). One specific oddity to perfume and fragrance advertising is that while smell is clearly a key part to the product it cannot be readily captured in either text or images (Lunyal, 2014). This makes the impression of the overall image particularly important (Toncar & Fetscherin, 2011) in triggering an emotion that leads the viewer to desire the product (S. K. Alioui, 2016).

Kress and van Leeuwen’s visual grammar (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2020) provides a useful tool for considering how the image’s design might seek to generate an emotional response in the viewer and whether, or not, colour as such is an important element (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2002). This allows consideration of how image construction can be used to create an impression of how the viewer will be perceived by others if they use the product (Marzuki et al., 2023). In this regard the use of celebrities as the model can be important as they may exemplify not just the effect of the fragrance but of a wider (desirable) lifestyle (Nylund, 2020).

Since creating such an ideal image of usage is so important this study compares adverts produced for a particular culture with those with a wider audience. This allows consideration of whether the semiotic modes vary across this divide.

Literature Review

Advertising can be seen as having two, closely related roles. In one it simply seeks to inform, this can be common in areas such as public health (Padilla & Padilla, 2022) or perhaps an indication that certain goods can be purchased at a given location. More often, advertising also has a role in the creation of demand (Kerr & Richards, 2021). In this format the traditional model is to identify a gap in the viewer’s experience that can be met by using the desired product and create an emotional desire to acquire the product. So thirst can be solved by drinking a particular brand of soft drink (Abokhoza & Hamdalla, 2019; Kotler et al., 2008) and related emotions can be relief, pleasure or even some feeling of status derived from using the product. This becomes more complex when the product is something like a perfume as framing the need, gap and how this can be met all become less clear cut. This in turn puts emphasis on how issues such as culture influence both the design of an advert and its interpretation (Alhuthali, 2024). An important step in this process is to trigger an emotional response that ensures the viewer responds as intended (Fennis & Stroebe, 2020) which can be more complex when the role of the product is nebulous (say compared to a brand of cola).

This emotional element is complicated in that awareness (or its lack) of the brand – and any pre-existing associations – may trigger particular emotions (S. Alioui, 2016). So if a given brand is disliked, then a negative emotional response becomes more likely simply on these grounds. Equally if the advert seeks to generate negative opinions it may be more likely to see an emotional reaction (Alhuthali, 2024) such as disgust. Appraisal Theory (Martin & White, 2005) captures the process by which a reader both understands an image and responds. Within this wider framework, Affect captures how a viewer understands the emotions embedded in the image, Judgement reflects how the image allows for an assessment of the character and behaviour of others and Appreciation has a wider social aspect as both creator and viewer will draw on the context (either within the text or in wider society) to inform their understanding and interpretation (Coffin, 2003).

Perfume advertising often clearly discriminates between adverts designed for a female, rather than male, audience. It is also marked by providing little real information (given it relies on image and text to capture what is really a smell) relying heavily on visual imagery (Tuna & Simões, 2012). Perhaps due to this the image is often divorced from usage of the actual product (Toncar & Fetscherin, 2011), in advertising terms this is described as the concept of visual puffery (Yang et al., 2019). The extent to which this disconnect is important is not clear and may relate to both the product and the analytic approach of prospective purchasers.

The visual element places focus on multimodal approaches to understanding meaning making. Some traditional theories such as the visual-verbal loop or information processing models (Tuna & Simões, 2012) have been used. However, given the importance of context in meaning making, and the need to combine text, images and colour in such a process then concepts of Visual Grammar are particularly useful (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2020).

The semiotic interpretation of text relies on three main concepts (Halliday, 1978) which in combination create a grammar based on the social world (ideational function), actions and interactions (interpersonal function) and the semiotic entities (textual function) (Halliday, 1978). In practice, especially once account is taken of the visual aspect, a variety of analytic structures have been developed including consideration of three major meta-functions, representational, interactive, and compositional meaning (Deng, 2023). Especially if the image includes human figures there is a valuable distinction to be made between the represented participants and the interactive participants in an image (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2020). A key to distinguishing between image composition (narrative) and the interpretation (the conceptual process) is whether a vector exists given that “vectors are the marks of the narrative process” (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2020, p. 82). In terms of the narrative element the vectors and the number (and actions) of the participants can be broken down into three sub-processes: action; reactional; and, speech and mental processes.

The action process has two main participants. The actor, who initiates a vector, and the goal which receives it (Alzahrani & Alhuthali, 2023). Usually the actor(s) will dominate an image and the goal is the objective of their actions. This in turn can be broken into three sub-processes depending on the type of interaction and whether or not there is an actual goal. In the latter case, the process is described as non-transactional but the others are represented according to the level of interaction (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2020).

The interactive participant (the reader or viewer) constructs meaning primarily by the contact between object and viewer with this mediated by image framing. Contact is the key as it depends on how the represented characters interact with the viewer, if they are looking directly at the viewer this forms a ‘demand’ (Zahrani & Alhuthali, 2024) in that a direct, emotional, response is triggered (ranging from empathy to disgust). If this is lacking then the image is an ‘offer’ in effect of passivity (Peng, 2022) and also reflecting that a future viewer is irrelevant to those represented in the image. In terms of demand, facial expressions are an important part of structuring the desired response.

Further information relates to image composition. Social distance relies both on the composition within the image such as how close the represented participants and how much of the participants is shown (Padilla & Padilla, 2022). This camera angle can also create a position of relative power between viewer and object depending on if it is looking down at the participants, up at them or at eye level.

In combination this provides a grammar to read the visual part of the image. Colour is a further important part to such meaning making but one marked by ambiguity and a lack of clarity (Harutyunyan, 2015; Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2002). Even more than in image interpretation, culture plays a critical role in the interpretation of any meaning provided by colour (Dohaei & Ketabi, 2015; Roberts & Philip, 2006).

The impact of culture both on form of advert and interpretation (Chang et al., 2009) is complicated but there are constraints such as the need to fit around the expectations of host country (Abokhoza & Hamdalla, 2019). Their study (Abokhoza & Hamdalla, 2019) compared two adverts by Pepsi placed in Egypt and Saudi respectively and found that they varied and reflected local cultural norms. The advert in Egypt “followed the theme of festivity and happiness while paying homage to classic cinema and pop culture in Egypt … . [the Saudi version] incorporated several cultural elements such as distinguished Saudi figures and symbols of public spirit” (p. 121). However, more often adverts are designed if not for a global market then for one wider than a single country. In this case culture becomes less salient except as a constraint on what can be shown.

Research Methods

Research into the efficacy of advertising has tended to use one of four main models (Toncar & Fetscherin, 2011). One is carry out an archival study of existing images with a large sample and then perform frequency analysis for variables such as gender, focus and so on. Experimental design such as response to variations of colour, image placement or indeed the use (or lack of images) is also widely adopted. Related to this are studies of reader response to adverts and to consider their varying interpretations. The final model, adopted for this study, is to review the semiotic modes deployed and their interaction.

The latter tends to small sample studies (Baldry & Thibault, 2006) as there is a need to describe in detail what semiotic resources are deployed, how they interact and the overall meaning making process at work (Alhuthali, 2024).

Cross national comparisons (Chang et al., 2009), especially comparison between disparate systems, lead to a concern that “comparisons of advertising content become problematic if the unit of observation is advertisements and the explanation of their differences across national borders is attempted at the cultural level” (Chang et al, 2009, p. 680). In this case, theory is useful to offset over reliance on small variables. In this study, the structure of visual grammar has been used to consider whether culture or gender have an over-riding role in the design of perfume adverts.

The images were selected using a Google search for perfume adverts with a human figure. Six are from adverts for Saudi companies (and five of these were aimed at the Saudi market) and six were from global brands. This allows a degree of comparison not between countries as such but between Saudi and other brands and markets.

Findings

The Saudi perfume market is substantial with domestic sales in excess of $0.5bn per annum and this is largely dominated by domestic firms (Statista, 2024). All of the chosen adverts in this section are produced by Saudi firms and placed online. One is different in that the target market is the US rather than Saudi consumers.

Figure 1 is a male fragrance made by a Saudi company (Ajmal Perfumes, 2023). The advert is only available on line and the accompanying slogan is: “Just the cool accessory you need for the summer. Shadow Ice from Ajmal Perfumes. Feel its cool aura envelop you and be with you like a shadow. Wherever you go.” However, this text is added above the image not as part of the poster.

In terms of visual grammar this is a demand, with the man staring back at the viewer, it is a close up image that shows most of the person and they are looking down at the viewer (suggesting superiority). Of note in this regard, the appeal is basically that you will look like this if you use this perfume. The pale blue background and white shirt are colours chosen to emphasise the message of ‘cool/ice’. As noted in the earlier discussion there is no information, implicit or explicit, as to the actual smell of the fragrance.

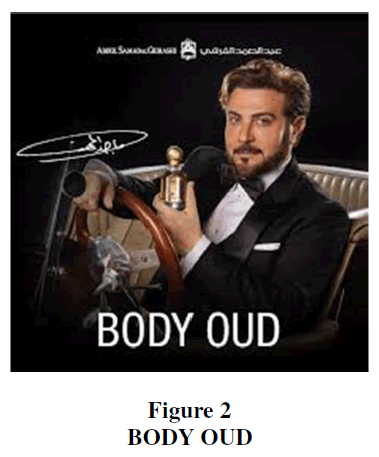

Figure 2 is another on line advertisement (this time on Facebook) by a Saudi company (Oud Amber & Perfumes, 2024). Again it is a demand, with the participant staring directly at the viewer, the person is set back, so it is less intimate than figure 1 and they on a level with the viewer. The wider image is of a classic, vintage, car set against a black background. Here colour plays the role of framing the image rather than having a direct semiotic role itself.

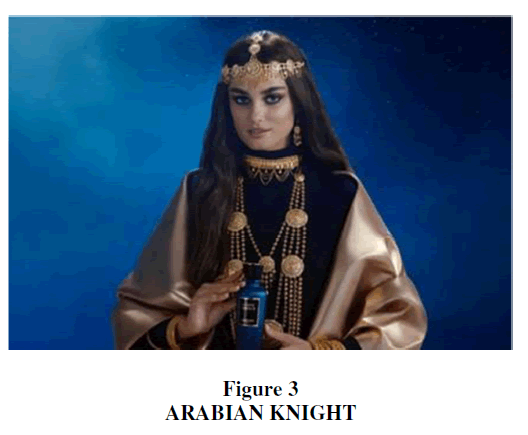

Figure 3 is for the Saudi firm Laverne (Arabian Knight, 2024) using an American model (Taylor Hill). The image is a demand, with an equal eye level and at a medium distance in the frame. Unlike figures 1 and 2, the dress style is deliberately invoking a certain image of Arabic female dress (though not at all compliant with traditional Saudi demands for women in public spaces). The choice of a blue background could indicate a degree of cool temperature or be chosen simply to frame the main figure. Again there is no idea of the actual smell of the fragrance.

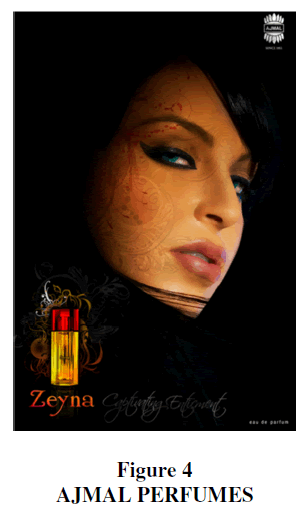

Figure 4 is for another perfume by Ajmal (Ajmal Perfumes, 2024) for women. As with the others it is a demand but with this moderated by only partially looking at the viewer. The image is close but only the head can be seen. The background colour primarily frames the model’s head but also reflects the degree of hiddenness in the rest of the image.

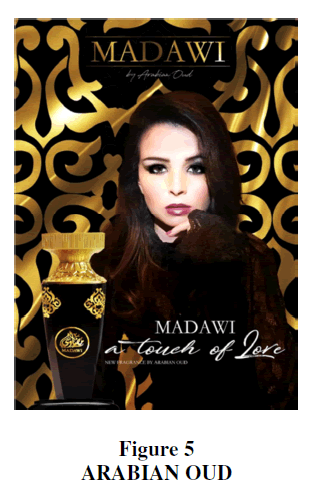

Figure 5 was originally place on Twitter (Arabian Oud, 2017) by a Saudi perfume company but in this case the advert was aimed at the US market. The image is centred on a demand, relatively close to the model and shows their torso and head. Unlike the other images, the actual perfume is prominently placed. The use of colour in the background is designed to give an air of opulence (the gold) and perhaps of secrecy (black).

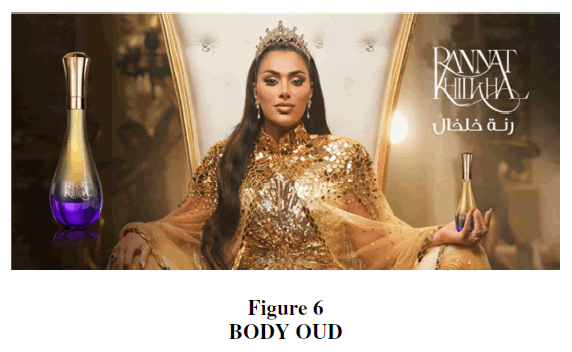

Figure 6 is another advert by the Saudi company Oud (Arabian Oud, 2024). Again it is a demand, with the head and torso shown but with some distance to the viewer. The perfume itself is prominent and the gold background, and dress, chosen to give an impression of expense.

It is worth noting that none of the female characters wear the full abaya but do meet the basic expectations of public modesty in that arms are covered and body shape obscured by the clothing. In effect, the images meet wider Islamic expectations rather than the more restrictive norms common in Saudi Arabia itself.

Non-Saudi adverts

This set of images reflect a number of global brands but are not country specific in their target audience.

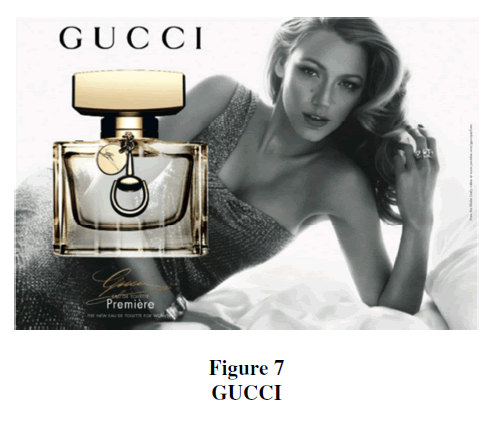

Figure 7 is for Gucci (Burton, 2014) and for the female perfume ‘Guest’. Again the offer is a demand with the model staring directly at the viewer, the model is at the mid-range and most of the upper body is visible. Of note the actual perfume is shown prominently. The bulk of the colour is light grey apart from the gold of the bottle.

Of note, in comparison to the Saudi adverts, are the bare arms and that the overall body shape is clear. However, as with the others, there is actually no information as to the actual smell of the perfume. The contrast to the Saudi adverts is clear in this regard in the what is seen to be culturally acceptable.

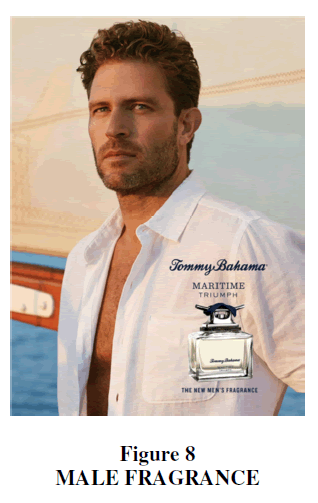

Figure 8 is for Tommy Bahama (Tommy Bahama, 2024). The company often uses a nautical theme in its advertising. This time the gaze is a demand, close up and of the upper body. The background is of a sailing ship. The white shirt and open front presumably is designed to invoke a nautical image of risk taking.

Figure 9 is an advert by Chanel (Elizabeth, 2024) and is unusual in its framing. While the model does face the camera, it is not the direct demand of most other images, the entire body is shown and the model is at the back of the image. In this case, the perfume actually dominates and the pink colour of the bottle (reflecting a feminine framing) dominates the white background.

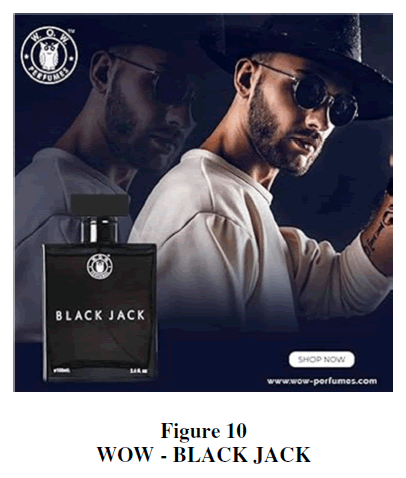

Figure 10 is for a male perfume black Jack placed on Amazon (WoW Perfumes, 2024). The model only partially faces the viewer so this is more of offer, only the upper body is shown the framing is in the middle of the image. The model is also shown less clearly in the same pose in the background. The emotional framing is one of self-confidence, daring and of mystery.

The front is dominated by the perfume bottle. The dark colour frames the subject and reflects the title of the fragrance.

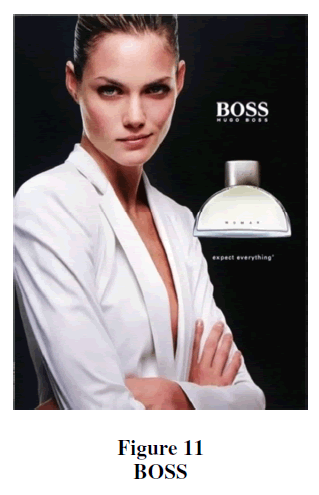

Figure 11 is for a female fragrance (Woman) by Boss (Aida, 2006) and placed on Pinterest. In the tag lines the perfume is described as seductive. This is a demand with the model foregrounded against a black background. The image is a close up and the white shirt is open making it somewhat revealing. Presumably, this is meant to capture the idea of being ‘seductive’ and of self-confidence.

The final image is another advert for a Gucci perfume (Chan, 2021). The model was the singer Miley Cyrus and it was released as part of a series of adverts. The model and the perfume are equally centred and close up with the background of a beach and sea. While the model is foregrounded they are making an offer to the viewer not a demand as their focus is on the perfume bottle. Here colour is important as her clothing reflects an inverse arrangement of the colours of the bottle. The golden cap is reflected in the sand and her trousers and again in the colour of her hair, There is some repetition from the pink of the bottle and the necklace Table 1.

| Table 1 Elements of Figures Discussed | |||||||

| Figure | Produced | Market | Contact | Emotion | Social Distance | Angle | Colour |

| 1 | Saudi | Saudi | Demand | Desire? | Close | Superior | Cool |

| 2 | Saudi | Saudi | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Neutral | Neutral |

| 3 | Saudi | Saudi | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Neutral | Cool |

| 4 | Saudi | Saudi | Demand (moderated) | Mystery? | Close | Superior | Neutral |

| 5 | Saudi | Global | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Superior | Opulence |

| 6 | Saudi | Saudi | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Superior | Opulence |

| 7 | Global | Global | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Neutral | Neutral |

| 8 | Global | Global | Demand | Masculine? | Close | Superior | Sea |

| 9 | Global | Global | Demand (moderated) | Whimsical | Distant | Superior | Feminine |

| 10 | Global | Global | Offer | Mystery? | Medium | Superior | Mystery |

| 11 | Global | Global | Demand | Seductive? | Close | Superior | Neutral |

| 12 | Global | Global | Offer | Relaxed | Close | Neutral | Neutral |

Summary

For this table, images are coded according to where they were produced and their intended market. Whether the framing is of a demand or an offer, close up or distant and whether they look down, at or up to the viewer. Finally, the role of colour is noted (in this case ‘Neutral’ is used if that is more a case of being part of the framing rather than seeking to achieve a particular emotion). The relevant emotion is noted, but inevitably this is very much subject to judgement. Figure 12 is unusual in that while the colour does not invoke an emotion as such, the entire image is dependent on the use and repetition of colour for its impact.

Even at this level there are degrees of ambiguity. In two of the images the demand is somewhat moderated either by partially turned away from the viewer or that, relatively, the human image is in the background. Equally while ‘desire’ is perhaps the dominant emotion what is unclear is if the desire is for the product or the model.

One final broad point, quite simply none of the adverts even try to describe the smell of the fragrance. Some hint at this with words such as cool or images of warm seas but that demands an imaginative leap by the viewer. In effect, perfume adverts seem to have very little relation to the product they are notionally selling. However, the actual product is clearly shown so that the potential buyer is aware of the brand. This makes the emotion invoked all the more important, in effect the advert has to sell an image of what wearing the fragrance will be like rather than provide information as to the actual smell.

There are no strong differences between the Saudi and Global adverts in most respects. The models mostly make a demand (the potential importance of this is discussed below), the framing is either close or medium range and the model is usually looking down at the viewer. Colour is as likely to hold its own semiotic mode as to be neutral in both groups. The main difference is in terms of dress. While none of the female models wear the Abaya or Hijab, they do cover their arms and body shape is obscured. In the international group, bare skin is common as is elements of body shape. To this extent, the producing culture plays a role in terms of what is seen as representing desire, offers a sense of mystery or is seductive.

This strongly suggests that the norms of the product outweigh other criteria. If the context was lacking (and there was for example no Arabic script) then in terms of semiotic modes there is no significant difference between the Saudi and International adverts. It is possible that a product that could be better described using the mediums of text, image and colour might lend itself to a more varied approach, but in effect, smell is critical to any perfume and quite simply all the advert can do is to suggest ways in which that (unknown) smell might prove to be alluring to an audience Table 2.

| Table 2 Gender of the Models in the Ads Discussed | |||||||

| Figure | Gender (model) | Gender (Target) | Contact | Emotion | Social Distance | Angle | Colour |

| 1 | Male | Male | Demand | Desire? | Close | Superior | Cool |

| 2 | Male | Male | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Neutral | Neutral |

| 3 | Female | Female | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Neutral | Cool |

| 4 | Female | Female | Demand (moderated) | Mystery? | Close | Superior | Neutral |

| 5 | Female | Female | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Superior | Opulence |

| 6 | Female | Female | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Superior | Opulence |

| 7 | Female | Female | Demand | Desire? | Medium | Neutral | Neutral |

| 8 | Male | Male | Demand | Masculine? | Close | Superior | Sea |

| 9 | Female | Female | Demand (moderated) | Whimsical | Distant | Superior | Feminine |

| 10 | Male | Male | Offer | Mystery? | Medium | Superior | Mystery |

| 11 | Female | Female | Demand | Seductive? | Close | Superior | Neutral |

| 12 | Female | Female | Offer | Relaxed | Close | Neutral | Neutral |

If the gender of the model and the target are taken into account there is a complete overlap as:

While clearly many fragrances can be used by either men or women and equally maybe bought as gifts there is a complete overlap between the gender of the model and the primary audience. This suggests that an important framing for the adverts is to present the potential user with an image of how they will be when they wear the fragrance. In this sense, the preference for superior camera angles supports the view that the image seeks to present an image of the viewer as much as to the viewer.

Equally commonly is that both male and female adverts are similar in terms of product placement. In a few the perfume bottle is relatively small (figure 2 for example) while in others it is more prominent (in figure 9, unusually, it actually dominates). This fits with the argument above, the advert wishes the viewer to see themselves and thus to make a purchase. The various shapes of bottles are important in helping the potential consumer identify the product.

Conclusion

Perfume advertising is complicated as the key element of the product (its smell) cannot be readily captured in a visual image even with supporting text. Clearly it would be possible to seek to describe the perfume on the poster using adjectives such as ‘woody’, ‘rich’, ‘spicy’ and so on but quite often this is not the approach used. Instead the overarching design is to show the potential purchaser an image of how they will be perceived in turn if they use the particular fragrance. The linkage is made by using a model of the gender of the target audience (or at least the audience who will use the perfume) and that the common framing of the image is a demand with a close up. In several cases a well known model is used, strengthening the life-style identification with the perfume, both that such a person uses it and also that you can adopt some of their appeal. Colour is sometimes used as a semiotic resource so blue as an indicator of ‘cool’, gold of opulence but in many of the adverts the colour exists as a background rather than a mode in its own right. The outlier in this regard with a careful set of interactions between the rest of the image and the perfume bottle.

This study suggests that cultural norms play only a limited role. Even in the Saudi adverts for the Saudi market the common domestic restriction on representations of women are set aside. The residual element is of full length clothing and obscuring body shape. However, even this is not unique to the Saudi adverts and is repeated in for Gucci.

This study reinforces the value of Visual Grammar as an analytic tool but also suggests that perfume adverts have their own internal logic that largely ignores both culture and gender. Perhaps even more than advertising in general, perfume adverts rely on the creation of an idealised image of the benefits of using the product. This suggests a need for more research of the differences between adverts for product types and, in particular, how hard or easy it is to reflect the actual product in a still image. In turn this might suggest important differences in the usage of semiotic modes depending, essentially, on how realistic the advert can be. In its current form, this paper suggests that culture forms a part of image composition but overall the norms of the product dominate. In particular, the presentation as a desireable self-image emphasises demand as a key vector with the person level with any viewer.

References

Abokhoza, R., Mohamed, S. H., & Narula, S. (2019). How advertising reflects culture and values: A qualitative analysis study. Journal of Content, Community and Communication, 10(9), 3.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Aida. (2006). Advert of the fragrance Boss Woman. Pinterest. Retrieved 8 July from.

Ajmal Perfumes. (2023). Ajmal Perfumes’ Post. LinkedIn. Retrieved 8 July from

Ajmal Perfumes. (2024). Ajmal Perfumes. Manish Photography. Retrieved 8 July from

Al Zahrani, B., & Alhuthali, M. (2024). Photographs and Cartoons: Differences in Interpretation of the Visual Semiotics. Open Journal of Applied Sciences, 14(3), 609-625.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alhuthali, M. (2024). The Construction of Attitudinal Meaning in Response to Food Advertisements: Six Case Studies. International Journal of English Linguistics, 14(4), 20-31.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alioui, S. K. (2016). Emotional integration and advertising effectiveness: Case of perfumes advertising. Journal of Research in Marketing (ISSN: 2292-9355), 5(2), 330-347.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alioui, S. K. (2016, 02/29). Emotional Integration and Advertising Effectiveness:Case of Perfumes Advertising. Journal of Research in Marketing (ISSN: 2292-9355), 5(2), 330-347.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alzahrani, B., & Alhuthali, M. (2023). Use of Vectors to Explore Visual Meaning Making. International Journal of Language and Literary Studies, 5(4), 33-46.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Amstrong, N., & Arman, A. (2023). Representation of Masculinity in the Hugo Boss Perfume Advertisement on Youtube. com. ELITE: Journal of English Language and Literature, 8(2), 109-124.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arabian Knight. (2024, 20 March). American model Taylor Hill promotes Saudi perfume brand Laverne. Retrieved 8 July from

Arabian Oud. (2017, 31 October). Madawi. Retrieved 8 July from

Arabian Oud. (2024). Body Oud. Oud Amber and Perfumes. Retrieved 8 July from

Baldry, A. P., & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis: A multimedia toolkit and coursebook.(Vol. 1, pp. 1-288). Equinox.

Burton, C. (2014, 10 July). Blake Lively Looks Stunning (Obviously) in Her New Gucci Campaign. ENews. Retrieved 8 July.

Chan, A. (2021, 30 July). Miley Cyrus appears in Gucci perfume advertisement. ZTYLEZ. Retrieved 10 July.

Chang, T. K., Huh, J., McKinney, K., et al. (2009). Culture and its influence on advertising: Misguided framework, inadequate comparative design and dubious knowledge claim. International Communication Gazette, 71(8), 671-692.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Coffin, C. (2003). Exploring different dimensions of language use. ELT journal, 57(1), 11-18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Deng, J. (2023). A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Posters-Based on Visual Grammar. International Journal of Linguistics, 15(6), 165-173.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dohaei, M., & Ketabi, S. (2015). A Discourse Analysis of Coffee and Chocolate Print Advertisements: Persian EFL Learner’s Problems in Focus. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3), S1.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Elizabeth, J. (2024, 4 January). Chanel’s Chance Perfume Ad Embraces Playful Luxury. Fashion Gone Rogue. Retrieved 8 July

Fennis, B. M., & Stroebe, W. (2020). The psychology of advertising. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. (No Title).

Harutyunyan, K. (2015). Colour terms in advertisements. Armenian Folia Anglistika, 11(2 (14)), 55-67.

Kerr, G., & Richards, J. (2021). Redefining advertising in research and practice. International Journal of Advertising, 40(2), 175-198.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kotler, P., & Armstrong, G. (2010). Principles of marketing. Pearson education.

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2002). Colour as a semiotic mode: notes for a grammar of colour. Visual communication, 1(3), 343-368.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2020). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lunyal, V. (2014). Examining the discourse of perfume advertisements: An analysis of the verbal and the visual. Journal of NELTA, 19(1-2), 117-131.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Martin, J. R., & White, P. R. (2003). The language of evaluation (Vol. 2). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nylund, S. M. (2020). Influencing luxury fragrance brand image with celebrity endorsement: Case study Miss Dior.

Oud Amber & Perfumes. (2024). Body Oud. Facebook. Retrieved 8 July from

Padilla, J. E., & Padilla, C. A. (2022). Multimodal Discourse Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign Posters: Visual Grammar Approach. Silliman Journal, 63(2).

Peng, Z. (2022). A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Movie Posters From the Perspective of Visual Grammar A Case Study of" Hi, Mom". Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 12(3), 605-609.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Roberts, S., & Philip, R. (2006). The grammar of visual design. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 22(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Statista. (2024, 1 March). Fragrances - Saudi Arabia. Retrieved 9 July from

Tommy Bahama. (2024). Maritime Triumph. Retrieved 8 July from

Toncar, M., & Fetscherin, M. (2012). A study of visual puffery in fragrance advertising: Is the message sent stronger than the actual scent?. European Journal of marketing, 46(1/2), 52-72.

Tuna, S., & Freitas, E. (2012). Gendered adverts: an analysis of female and male images in contemporary perfume ads. Comunicação e Sociedade, 21, 95-108.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

WoW Perfumes. (2024). Black Jack Perfume for Men. Amazon. Retrieved 8 July from

Yang, D., Xie, N., & Su, S. J. (2019). Claiming best or better? The effect of target brand's and competitor's puffery on holistic and analytic thinkers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 18(2), 151-165.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 22-July-2024, Manuscript No. JOCCC-24-15077; Editor assigned: 23-July-2024, Pre QC No. JOCCC-24-15077(PQ); Reviewed: 05-Aug-2024, QC No. JOCCC-24-15077; Revised: 09-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. JOCCC-24-15077(R); Published: 15-Aug-2024