Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Payments into the Company by Shareholders: Debts to Shareholders or Capital Reserves to Be Recorded in Equity?

Maria Silvia Avi, University in Venice

Citation Information: Avi, M.S. (2023). Payments into the company by shareholders: debts to shareholders or capital reserves to be recorded in equity?. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 27(2), 1-28.

Abstract

It may make shareholder loans either a loan or a capital contribution. In the first case, the loans are standard, while in the second case, the shareholders' loans constitute reserves that must be recognised in the company's equity. Both loans and capital reserves are subject to rules that vary from country to country, but, in general, several principles distinguish each legislation. This article will focus our attention on these items to understand their differences and similarities.

Keywords

Loans from Shareholders, Payments on Account of Capital, Payments on Account of Future Share Capital.

Introduction

Shareholders of a limited liability company may make payments to the company either through loans or by way of capital as a substantial part of equity. The difference between the two types of payment is noticeable: while in loans, there is the intention to have the capital lent back to the company, in capital contributions, the purpose is to increase the company's capitalisation by creating an equity item. The legal differences between the two types of payments are profound and well illustrated by the code and the doctrine, which underlines the characteristics of both payments. However, it should note that, in practice, shareholders often pay money to the company to cope with a momentary unbalanced financial situation while avoiding the charging of such payments to capital. These payments are essentially capital payments, but this is not apparent from the contract signed between the company's shareholders (Aisbitt, 2002). The Italian Civil Code and the specific regulations relating to these loans have very clearly set out the characteristics of debts, so that the practice of financing that shareholders make to deal with the under-capitalisation of the company utilising payments which, in reality, are capital contributions, but formally appear to be simple debts, cannot be implemented. Very frequently, these contributions are defined as debts, loans, mortgages, with a consequent right to repayment equal to that of the other creditors (in this regard, however, see the considerations that we will make later on about the legal rule of the subordination of debts to shareholders). These contributions are therefore disguised as loans when, very often, they are capital contributions that serve to save the company from a financial and equity crisis that could become irreversible.

The circumstance of reporting real loans in equity or capital payments in debt has a detrimental effect on financial reporting. This distorts communication to the outside world and distorts the financial reporting ratios if financial and capital ratios are calculated based on erroneous and incorrect financial reporting. Although it may seem illogical, this behaviour is widespread as the financial reporting analysis is generally carried out on the data of the published financial reporting and therefore on the inaccurate, incorrect and not understandable data resulting from a false entry of accounts in the financial reporting itself.

In the following pages, we will have the opportunity to highlight, in an analytical way, the characteristics of the loans, of the capital account payments, with particular reference to the payments in future capital increase and to the consequences on the financial reporting ratios deriving from an erroneous entry of the accounts deriving from the masking of the substance of the account itself (payments that are capital account payments defined as debts and therefore recorded among the company debts or, on the contrary, capital account payments that, in reality, are debts and therefore are improperly recorded in the equity.

Shareholder Loans: Characteristics and Observations

Various types of limited liability companies are regulated in Italy. The most common legal form is the joint-stock company, followed by the limited liability company. There are other legal forms of joint-stock companies on which we will not focus our attention because of their peculiarities (such as, for example, cooperative societies, which are characterised by particular missions and legislation adapted to those missions). In general, the rules of public limited companies are referred to by the other forms of limited companies. For loans, however, the reverse is true. The law governing loans from shareholders understood as debts are included in the legislation concerning limited liability companies. Article 2467 - Shareholders' loans - as amended on 1 September 2021 reads:

The repayment of shareholders' loans in favour of the company shall take priority over the satisfaction of other creditors (Alexander, 1993; Alexander & Schwencke, 2003).

For the preceding paragraph, shareholders' loans in favour of the company shall be understood as loans, in whatever form they are made, which have been granted at a time when, also in consideration of the type of activity carried out by the company, there is an excessive imbalance of debt about equity or in a financial situation of the company in which a contribution would have been reasonable (Alexander & Schwencke, 1997).

However, the Italian legal doctrine is unanimous that it should apply the general principle imposed by that article in Article 2467 cc to the limited liability companies since that article does not identify a specific rule but a general principle that seems logical to apply all companies. It can find no similar regulation in other capital companies' laws, including joint-stock companies. One part of the scholars points out that, in doubt concerning the application of the above rule also to joint-stock companies, the extension should undoubtedly be accepted as a rule, at least when joint-stock companies are representative of an entrepreneurial reality similar to most limited liability companies, i.e. medium and small-sized companies with a sufficiently limited shareholder base (Alexander & Jermakowicz, 2006).

In judgment no, this position was also affirmed by the Court of Cassation (last instance in Italy). Sentence n. 16291 of 2018. The Court of Cassation had already adopted the latter interpretation, having previously pointed out that the rationale of the principle of subordination of the repayment of shareholders' loans, laid down by Article 2467 of the Italian Civil Code for limited liability companies, is to counteract nominal under capitalisation (Alexander & Nobes, 2013). For limited liability companies, consists in contrasting the phenomena of nominal under capitalisation in "closed" companies, determined by the convenience of the shareholders in reducing their exposure to business risk, by placing capital at the disposal of the collective entity in the form of financing rather than in the form of a contribution; and this ratio - it has been said - is also compatible with other corporate forms, as can be deduced from Article 2497- quinquies of the Italian Civil Code, It has been said that this rationale is also compatible with other forms of companies, as inferred from Article 2497- quinquies of the Italian Civil Code, given that such rule extends its applicability to loans made in favour of any company by those who exercise management and coordination activities. Therefore, the principle has been affirmed that Article 2467 applies to shareholding companies after a concrete evaluation, in particular, it must be assessed whether the company, due to its small size or the structure of its social relations (family or, in any event, restricted structure), is suitable from time to time to justify the application of the provision mentioned above (see Court of Cassation judgment no. 14056 of 2015). It must confirm other such approaches since it is true that the subordination rule tends to sanction the so-called "nominal under capitalisation" of companies, in which the company that needs its means is instead financed by the shareholders through the provision of debt instruments, resulting in the artificial pre-constitution - in a situation of equity imbalance of the company - of positions homogeneous with those of the creditors. As can be seen from what has been said by the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court also considers that Article 2467 of the Civil Code may be applied to other forms of companies other than limited liability companies where the form and the corporate, entrepreneurial and organisational structure of the company are similar to the typical form of a limited liability company (i.e. small or medium size, number of employees not too high, share capital not high and small shareholder base) (Anda & Puiga, 2005).

Before addressing the subordination of shareholder loans, it is first necessary to highlight the general characteristics of shareholder loans as debts. Italian law does not provide for special rules regarding shareholder loans. Such loans constitute debts and must be recognised as part of all the company's debts. The Italian legislation provides that it must recognise these debts with a specific item and, therefore, are not added to other types of loans and debts. Loans from shareholders are freely agreeable. There is no provision for a shareholders' resolution approving such a decision. The loan amount is independent of the percentage of share capital held by the shareholder. Although the legislation does not provide any particular structural forms of loans and specific written forms of such contracts, the doctrine agrees that it is appropriate to give the agreement a written form. Such a contract must clearly and explicitly identify the amount to be paid, the deadline for repayment and the interest applied to such a loan (Ballwieser et al., 2012).

To prevent the loan from being the subject of legal problems, it is advisable to include a clause in the company's memorandum and articles of association providing for shareholders to make loans to the company (Burchell et al., 1985).

If the shareholder decides to make a non-interest-bearing loan, the absence of interest expense for the company must be expressly stated in the contract to highlight that no harmful income components for the company arise from this financial relationship. The fact that the loan is not interest-bearing should also be proved by dated business correspondence (i.e. dispatch without envelope) showing that no interest is payable by the company.

1. It should also provide this information in the notes to the financial statements that make up the financial reporting.

2. It should be noted that where the contract provides for the application of interest payable by the company, the rate applied to the company is generally lower than the rate that the company usually has to pay to other lenders such as banks and credit institutions. Often such loans are also characterised by the fact that they are easy to disburse, and the necessary liquidity can obtain the company needs quickly.

3. It should be noted that the tax law stipulates that for borrowed capital, interest is presumed to be received at the time and in the amount agreed upon in writing unless proven otherwise. If the maturity dates are not fixed in writing, interest is presumed to be received in the amount accrued in the tax period. If the amount is not determined in writing, interest shall be calculated at the statutory rate. The rule refers here to interest-bearing loans.

In Italy, it may only loans from shareholders if it holds at least 2% of the share capital and has been registered in the shareholders' register for at least three months. In the absence of these two characteristics, it can implement no loan to the company (C. I. C. R. DELIBERAZIONE 19 July 2005 n. 1058 Raccolta del risparmio da parte di soggetti diversi dalle banche. (Resolution no. 1058). (OJ no. 188 of 13-8-2005).

Based on what has been stated above on the possibility of applying rule 2467 of the Italian Civil Code also to legal forms other than limited liability companies, the latter rules mentioned being able to make loans to the company must also be considered applicable joint-stock companies (Benston et al., 2006).

The repayment of the shareholder loan, like corporate debt, must take place on the due dates laid down in the loan agreement. Nothing prevents the loan from being renewed at maturity. Reading the article quoted in the preceding pages, one understands that, in some instances, the subordination of the repayment of the shareholders' payment applies. However, such reimbursement finds a significant limitation in Article 2467 of the Civil Code, applicable, as I have already pointed out, both to limited liability companies and to joint-stock companies. In particular, such compliance concerning all other corporate debts applies when (Burchell et al., 1980):

1. The shareholders' loans to the company those, in whatever form they are made, which were granted at a time when also in consideration of the type of activity carried out by the company, there is an excessive imbalance of the indebtedness concerning the shareholders' equity;

2. or in the company's financial situation in which a contribution would have been reasonable.

The Research Institute of Chartered Accountants emphasises that the legal provision governing the subordination of shareholder loans has not laid down any objective criteria to identify the existence or otherwise of the conditions entailing the application of Article 2467 but has preferred to indicate only general principles. The report accompanying the decree that amended Article 2467 of the Civil Code invites the interpreter to adopt a criterion of reasonableness that considers the company's situation and compares it with the behaviour that could reasonably be expected in the market. This means that the two conditions mentioned above, which trigger the subordination of loans, are only general principles that must be carefully interpreted by the directors of companies preparing financial reports.

Concerning the first condition, it noted that the excessive imbalance of debt concerning equity is not only not objectively identifiable, but is also extremely problematic, even using the concepts of corporate doctrine. About the second condition, on the other hand, it has been observed that the reference to the criterion of reasonableness could certainly broaden the scope of application of subordinated financing because, if a company needs financial means, it is quite likely that the contribution of the shareholders must always be considered reasonable. In any event, the vagueness of the general principle of reasonableness ends up giving rise to numerous disputes in the case law as to its meaning Research institute of chartered accountants 2006 (Delvaille et al., 2005).

If one of these conditions occurs, the loan can only be repaid, regardless of what is stated in the contract signed between the company and the shareholder, if all other creditors have been satisfied and, if it occurred in the year preceding the bankruptcy, it must be repaid.

It is clear that this rule serves to protect the company's creditors. Indeed, in both cases, the company obtains a loan from shareholders in a condition where the financial situation has deteriorated, which, of course, could lead to an overall financial collapse of the company, resulting in its bankruptcy. In the second case mentioned, the financial and equity situation was unbalanced due to too many debts compared to the equity. Therefore, the management should have advised the shareholders to increase the capital and not to increase the company's overall debt (Cristea & Saccon, 2008).

It should note that the two situations causing the shareholder loan subordination must be present when the loan is paid out. Therefore, the loan is already subordinated because the financial situation in which the payment is made is deteriorated or, in any case, highly unbalanced. As such, the management should not have proceeded to further the company's indebtedness, even if towards the shareholders (De Franco et al., 2011).

From the previous, it can be understood how the subordination of shareholder loans, even though they are debts, makes the loans analogous to capital contributions. The loan repayment can be made only after all the company's creditors have been paid. Most legal theory agrees that the subordination of shareholders' loans does not apply if, at the time the shareholder granted the loan, the company's financial and asset situation was balanced. Therefore, any subsequent deterioration of the company's status is not relevant. What matters is the moment at which the corporate debt arises; the situation after that is not relevant concerning the above-mentioned subordination of loans (Di Pietra et al., 2001).

A particular remark should be made about the correct meaning of financing "in any form whatsoever" mentioned in Art. 2467 of the Civil Code. The various scholars who have dealt with the matter have explained this concept in multiple ways. Some of these scholars have stated that such financing may also include credits that have expired and are therefore collectable since the rule does not explicitly refer to the payment of money. Other authors consider that financing in kind would not fall within the application of the subordination provided for by Article 2467 of the Civil Code since the repayment is intended as repayment in cash or bank cheque, while other scholars, such as the researchers of the research institute of chartered accountants, maintain that such contributions entirely fall within the definition of "financing in any form made". It should note that the judges unanimously believe that it should also include financial leasing contracts should among the forms of financing as this type of contract implies the repayment of the periodic fee paid the year before the bankruptcy and the consequent subordination of the residual debt (Ewert & Wagenhofer, 2005).

Regarding the nature of the subordination, it is worth recalling the observations of Fregonara, who observes that The issue of the scope of application of the rule in question has significantly engaged doctrine and jurisprudence, recording opposing positions. On the one hand, there are the supporters of the so-called procedural thesis according to which subordination should operate exclusively in the context of a creditors' competition that has already been formally opened, i.e. collective insolvency proceedings or voluntary liquidation of the company: subordination is to be understood as the imposition of an order of priority between the claims of external creditors and the claims of shareholder-creditors, which only takes place at a stage when the number of creditors outside the company is "crystallised". In this perspective, Article 2467 of the Civil Code sanctions a general principle of operation of the company in crisis. It does not allow the directors to refuse to repay the financing to the shareholder or the other company of the same group in any case since the subordination produces effects exclusively in a phase of collective or individual execution on the assets of the company; hence its application outside the liquidation would presuppose the exercise of executive action by the financing shareholder against the company. On the other hand, the majority doctrine maintains that subordination already operates during the company's life, ensuring that the sums paid remain in the company's assets through compliance with the rule of priority of other creditors. In the absence of contraindications that can be deduced from the regulatory text, the generalised application of the first paragraph of Article 2467 of the Civil Code is therefore considered legitimate, and this is because of the legislator's intention to effectively protect the other creditors of the company against what could be improper behaviour on the part of the financing shareholder: the supposed "correlation between subordination and enforceable competition does not seem necessary, since certainly the ideal ground for applying the rule is that of competition between creditors, but it can also apply independently of this circumstance, determining a sort of virtual competition between all the company's creditors". In this perspective, subordination affects the substantive legal relationship underlying the financing, conditioning the collectability of the claim. As noted, Article 2467 of the Italian Civil Code introduces a general principle of correct financing of the company, the valorisation of which postulates its operation on the substantive level. This solution is confirmed by inserting the rule in a common law rule that is not limited to the case in which insolvency proceedings are pending. It seems, moreover, that only the acceptance of this thesis provides an adequate response to the phenomenon of under capitalisation, inducing companies to equip themselves with adequate capital resources (Fregonara, 2020).

The only explicit rule in the context of the regulation of joint-stock companies (although, as noted above, doctrine and case law unanimously believe that Article 2467 of the Civil Code concerning limited liability companies is also applicable to joint-stock companies) is Article 2497 quinquies which provides: "Article 2467 applies to loans made to the company by those who exercise management and coordination activities over it or by other entities subject to it."

This means that when a group company with management control over other companies or other entities makes loans to those companies, the principle of subordination of debts set out in Article 2467 of the Civil Code applies. This has been established to avoid a subjective and discriminatory unequal distribution of business risk in groups of companies between the companies exercising control in the group and the companies that are subject to it, mainly when situations of financial imbalance and under capitalisation characterise them. It should note that the rule does not refer to shareholder status in the financed company. The only condition required for the applicability of the law is the lender's performance of management and coordination activities. Therefore, the rule concerns the shareholder of the financed company and its directors, holders of financial instruments or any other person even in the absence of shareholder status. Therefore, it is sufficient that the management and coordination activity is present and the imposition of Article 2497 quinquies is triggered without the lender needing to be a shareholder (Godfrey & Chalmers, 2007).

Finally, it should note that the directors may agree with the financing shareholders to convert the debt into a capital loan. In addition to the agreement of the financing shareholders, approval by the ordinary shareholders' meeting is also required in this case. The financing shareholders may, at any time, waive the collection of their claim against the company. When this occurs, the amount of the debt is transferred to an account to be recorded in the company's equity as a reserve. Readers are referred to the next paragraph for a summary explanation of these reserves (Haller, 1992).

Loans from Shareholders by Way of Capital: Recognition within the Company's Equity

As we have pointed out in the preceding pages, loans from shareholders may have two different purposes:

1. to provide the company with a loan of which the shareholder wants repayment at fixed dates. In this case, the loan is a normal debt for the company

2. to provide the company with a loan with the intention of strengthening the equity of the company without, at that moment, increasing the share capital.

In this case, the loan does not represent a debt but a share in the company's equity. Such financing will be returned to the shareholders only at the time of the dissolution of the company and, as with all equity items, such sums must be subordinated to the company's debts. As confirmed by the Court of Cassation in its judgment No. 16049 of 29 July 2015, the shareholder's contribution results in the definitive acquisition of the company's assets of the sums paid, which are to be assimilated to risk capital, to which they must be equated for material purposes. The reserve thus formed, like the ordinary or optional reserves for the portion exceeding the legal reserve, is therefore generally available, but its distribution does not constitute a subjective right of the shareholder (Haller, 2002).

Claiming that, in such a case, the right to restitution exists at the end of the liquidation of the company if there is a residue to be distributed among the shareholders, after all creditors have been paid, means, then, nothing more than assimilating such contributions to contributions and risk capital: they too will be returned at the end of the liquidation of the collective undertaking (Halle et al., 2003).

In the case of such contributions, the restitution is subordinated to the satisfaction of the company's creditors, just as in the case of the contributions made by the shareholder: this is a mere possibility, depending on the situation of the company's assets at the time of the liquidation of the company and on the possibility that there will be sufficient values left in those assets for repayment after the creditors have been fully satisfied.

In substance, therefore, as stated by the Court of Cassation in judgment no. 7692 of 31 March 2006.

It is true that the so-called payments made by shareholders on account (or with another analogous term indicated), while not immediately increasing the share capital and while not attributing to the relevant sums the legal status of capital (so that they do not need to be the result of a specific resolution of the shareholders' meeting to increase the said capital), nevertheless have a cause which is normally different from that of a loan and is instead comparable to that of risk capital. However, they have a cause which, as a rule, is different from that of a loan and can be assimilated to that of risk capital, with the consequence that they do not give rise to credits payable during the life of the company and can be claimed by the shareholders in repayment only upon dissolution of the company and within the limits of any residual assets of the liquidation financial reporting. As will be shown later, there is nothing to prevent previously created reserves from being returned to shareholders if there is a shareholders' resolution and there is the technical possibility of identifying forms of payment to be made to shareholders (cash or corporate assets). The possibility of distributing reserves is always possible provided that the reserves are available and that there is a capacity of corporate assets. It should be noted, however, that in the event of the company's bankruptcy, what has been distributed to the shareholders in the preceding year must be repaid as it is subject to the subordination of shareholders' loans, a principle that applies, as can be seen, not only to debts but also to shares in Equity.

The concept of shareholders' loans representing simple corporate debts has been explained in detail in the preceding pages (Haller & Eierle, 2004). In the following pages we will focus our attention on loans that represent equity shares.

Such financings can be distinguished in:

With regard to the differentiation between loans and financing identifying equity shares, doctrine and jurisprudence have identified a number of criteria useful to establish a presumption of financing as risk and not as loan (Hanlon & Heitzman, 2010). These principles may be summarised as follows:

1. share capital increase: this reserve consists of amounts intended for the share capital increase when the share capital increase procedure is still in progress at the time of closing the accounts, i.e. after the share capital increase resolution but before its execution;

2. future share capital increase: this reserve consists of amounts to be used if, at some future date, the company decides to increase the share capital. In this case, there is no decision already taken on the share capital increase. The reserve is created on the assumption that in the future the company decides to increase the share capital but the procedure has not yet been opened with any formal act;

3. capital account: this reserve is a part of equity but has no particular destination.

4. coverage of losses from previous years: this reserve is created when there are losses from previous years in financial reporting or during the year when it is realised that the profit and loss account will close with a loss. The reserve will be used to cover such losses in the following year.

5. non-repayable loans: this reserve is created when the company is undercapitalised and the shareholders wish on the one hand to increase the capitalisation and on the other hand not to increase the share capital.

6. Absence of a repayment term;

7. No provision for the accrual of interest expense to be borne by the company and, therefore, non-frual of the shareholders' loan;

8. Lack of credit of the company towards third parties;

9. Unbalance of the loan conditions in favour of the company;

10. Amount of the loan in relation to the fully paid-up share capital

It should note that loans representing equity but not directly charged for sharing capital are, in fact, similar to the contribution of share capital. The difference between the two types of financing derives from the circumstance that, in the first case, the share capital is not increased. Therefore, there is no modification of the company's agreements and consequently no need to modify the company's bylaws.

Such financing does not provide for an obligation of repayment by the company. Of course, there is nothing to prevent the shareholders' meeting from approving a distribution of unrestricted reserves and thus, indirectly, returning the money or other contribution to the shareholders.

Scholars agree on the circumstance that payments made as capital, in particular by way of a future share capital increase, not proportionally made by all shareholders, may create equity reserves linked to the shareholder who made the financing, unlike non-repayable loans, which are always deemed to be acquired by the company for the benefit of the entire shareholder base, even though they have been paid proportionally to the share capital held by each shareholder. Even in the case of "ring-fenced" reserves, i.e. reserves linked to particular shareholders, the rule of subordination of payment to all company creditors still applies. The shareholders will only be subject to restitution if there remains an amount higher than the company's total liabilities to third parties from the sale of the assets. In its judgment No. 31186 of 3 December 2028, the Court of Cassation held that an objective credit function is essentially excluded in the case of payments on account of a future capital increase since, if the growth takes place, they will automatically be included in it, whereas, if the increase does not take place, they will be returned, but not because they were made as a loan, but simply because the planned event - the capital increase - has not been completed. The Court of Cassation, in the judgment as mentioned above, also points out that, for the shareholder's "donation" to be brought under this category, it is necessary for the subordination to a capital increase to be clear and unequivocal, through the ex-ante indication of sufficiently specific and detailed elements, which led to the conclusion that it was agreed between the shareholders not to make a payment tout court in favour of the company's coffers, but of a payment having the concrete title and cause of participation in the company's capital through a future contribution, which, although merely postponed concerning the time of the physical transfer of the sum, is nevertheless intended from the outset, according to the overall operation planned by the shareholders, to increase their respective shareholding in absolute terms.

This principle has been reiterated several times by the Court of Cassation, which, in various judgments, has emphasised what has been illustrated above: that, in such cases, the resolutive condition of the failure to increase the capital is applicable when a future increase for which the payment is intended is identified or identifiable: but this is not by way of repayment of the sum given as a loan, since the justifying cause for the asset allocation made by him in favour of the company, such as repayment of the undue payment, must then be considered to have ceased to exist;

1. that, therefore, an objective credit function is to be excluded in the case of payments on account of a future capital increase, given that, if the growth takes place, they automatically flow into it, whereas, if the growth does not take place, they must be repaid, but not because they were made by way of financing, but simply because the event planned - the capital increase - has not been completed (thus Supreme Court of Cassation judgment no. 31186 of 3 December 2018);

2. that the recognition in financial reporting takes place in such cases as a reserve, and not as a shareholders' loan and as a debt of the company to them;

3. that, therefore, the principle of law has been affirmed, according to which "it is not up to the administrative body to post in financial reporting the donations of money by the shareholders in favour of the company, nor to change the relevant item, after the original posting, since it must strictly reflect the actual nature and concrete cause of the same, the assessment of which, in the interpretation of the will of the parties, is referred to the appreciation reserved to the judge of merit" (Court of Cassation 22.12.2020, judgment no. 29325).

This is because of the general principle of determinateness or determinability under Art. 1346 of the Civil Code, according to which the subject matter of the preceptive content of a negotiated agreement must always be identifiable with sufficient certainty. The mere words used are therefore not in themselves exhaustive, since a payment may well be called, in the corporate and accounting documents, as being made "on account of a future increase in share capital", but at the same time not at all accompanied by those detailed indications (e.g. the final term within which the increase will be decided, but also other characteristics of the same), which alone qualify the payment as being attributable to the category in question. In such a case, therefore, the recognition in financial reporting always takes place as a reserve, and not as a shareholders' loan; but, for the conditional restitution obligation to arise, it must also be highlighted that the contribution is susceptible of restitution to the shareholders under the resolutory effect connected to such type of contribution, which therefore did not occur definitively (unlike the other contributions).

The Italian Supreme Court of Cassation, in its judgments 16393 of 24 July 2007 and 2314 of 19 March 1996, ruled that it has now been clarified that there are various ways in which a shareholder can give money to the company, namely contributions, shareholders' loans, non-refundable payments or capital contributions and payments aimed at a future increase in the capital; that it is thus specified, for what is relevant here, that in the last category, the donation of money is aimed at releasing the debt for the subscription of a future increase in share capital employing a subsequent waiver, which the shareholder will put in place after the shareholders' resolution to increase the share capital and its subscription: it is referred to as a "personalised" or "tagged" reserve, in that it is exclusively attributable to the shareholders who have made the payment concerning the amount of the sums paid by each.

It should be noted that, given the major differences between equity reserves and between such reserves and loans understood as loans and, therefore, company debts, the Supreme Court has deemed it necessary to emphasise that the real substance of the loan derives from the company's intrinsic desire to use that loan for certain transactions. Therefore, the directors are not free to recognise the financing as debt or part of the equity in financial reporting, nor are they free to change the destination of the financing, since it is necessary that the recognition in financial reporting strictly reflects the actual nature and the real cause for which such financing was made. This, according to the Court of Cassation (Court of Cassation judgment no. 29325/2020), must be assessed by the judge on the merits as only that body is appointed to evaluate the actual substance of the financial reporting items. Decisive, therefore, in the qualification of the contribution is the interpretation of the will of the parties, left to the prudent appreciation of the judge of merit. In particular, the latter must ascertain whether it was a financing relationship referable to the scheme of the loan or an atypical contribution contract, and, in the latter case, whether it was - unequivocally - conditioned or not, in the repayment, on a future increase in the company's nominal capital. The investigation of the contribution may take into account any element, such as the clauses of the statutes providing for such payments, the conduct of the parties, the purposes pursued, the accounting records, the financial reports and any other circumstance of the concrete case, capable of revealing the common intention of the parties and the interests involved.

It follows from this principle of law, which must now be affirmed, that it is not up to the administrative body to enter in the financial reporting the donations of money by the shareholders in favour of the company, nor to change the relevant item after the original entry, since it must strictly reflect the actual nature and concrete cause of the same, the assessment of which, in the interpretation of the parties' intentions, is left to the appreciation reserved to the judge of the merits.

As stated by the Supreme Court of Cassation 29.7.2015 judgment no. As stated by the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation in its decision no. 16049 of 29 July 2015, the interpretation of the parties' intentions becomes decisive, as the use of non-codified formulas requires the utmost caution in ascertaining the actual intention of the parties, shareholder and company, between whom established the relationship: it is necessary to determine whether the relationship was a financing relationship that can trace back to the mortgage model or an atypical contribution contract, and, in the latter case, whether it was conditional on a future increase in the company's nominal capital.

Given the frequent use, often for tax purposes, of terms not intended in their technical-legal meaning, it is "necessary not to stop at the mere denomination used in the company's accounting records, but instead to turn our attention above all to how the relationship was concretely implemented, to the practical purposes to which it appears to be directed and to the interests underlying it" (as already required by the aforementioned Court of Cassation, judgment no. 2314 of 19 March 1996): in short, to the agreements between shareholders and the company.

The investigation on this point must consider the clauses of the articles of association providing for such payments, the accounting records, the financial reports, the conduct of the parties and any other circumstances of the case.

If, moreover, it appears that the shareholder made the payment with a view to a future increase in the share capital, from which he would by definition have benefited, and that, having changed his perspective within the collective entity, he intended to leave by disposing both of the shares. Separately from that credit, this element could indicate the qualification of the payment in the third type described above.

As the Court of Cassation held in judgment no. 4261 of 19 February 2020, acceptance of a claim by which a shareholder of a capital company seeks the restitution by the company of sums previously paid by him requires proof that the payment was made for a reason justifying the claim for reimbursement. That proof must be drawn not so much from the name under which entered the amount in the company's accounts but from the way the relationship was implemented, from the practical purposes to which it appears to be directed and from the interests underlying it (Hopwood, 1972).

It is clear from the above that, to verify the true nature of shareholders' loans, one should not stop at the name attributed to the account referring to that loan. Still, it is necessary to verify the substantial purpose of the payment and how it is made. As stated above, in the event of a challenge to financial reporting, the judge on the merits will verify the substance of the accounting entry and check the correctness of the entry in financial reporting. The use of such expressions does not make it possible to confirm whether the payments made constitute a loan, even if non-interest-bearing, or instead of a capital contribution, and therefore, whether the company is obliged to repay, or whether it can definitively acquire the contribution (Hopwood, 1973).

The research institute of chartered accountants has also pointed out that, to complicate the identification of the case further, the shareholders themselves often contribute, with the collaboration of the directors, to manipulate the practice of payments based on the company's economic performance. It often happens, for example, that during the regular operation of the company, the shareholders present the payments as contributions as part of the net equity, to create the confidence of the banks in the adequacy of the company's means, and then, however, in the event of a crisis in the company, they consider them to have been made by way of a loan, requesting repayment (Hopwood, 1974).

In this respect, the observations of Palumbo (Palumbo, 2021) are particularly clear. Referring to the judgment of the Court of Cassation no. 4261 of 19 February 2020, Palumbo points out that in practice, however, the distinction appears less easy to identify due to the frequent use of imprecise, intentionally ambiguous terms, which do not allow the financial contribution to be traced with certainty to one type of payment or the other. It does not therefore appear sufficient, for the purposes of the legal qualification of the payment, to stop (as the order in question reasonably reiterates) at the denomination of the accounting records, but it is necessary to reconstruct the contractual will and the underlying interests, since it is a quaestio voluntatis on the substantial purpose of the operation. To this end, the accounting records may well represent a useful element for the qualification of the case, only it cannot be ignored, as also observed by the Court, that, given the different method of recording shareholders' loans and payments, the results of financial reporting or of the journal cannot take on decisive value, let alone confessional value (see also Court of Cassation, 20 April 2020, no. 7919). They are therefore freely assessable by the judge according to his prudent appreciation.

Consistent with the above, the majority of case law, also followed by the order in question, has affirmed the residual probative value of the results of accounting records (see Court of Cassation, 27 June 2017, judgment no. 15950; Court of Cassation, 3 December 2014, judgment no. 25585; Court of Cassation, 23 February 2012, judgment no. 2758).

In the context of this interpretation, it will therefore be necessary to assess a plurality of elements capable of revealing the negotiating intention. These include the conclusion of any shareholders' agreements ....... the fact that the payments were made by all participants ...... or the content of the notes to the accounts (Court of Cassation, 8 June 2018, judgment no. 15035; and so what emerges from the notes to the accounts. 15035; as well as the contents of the shareholders' meeting resolutions, provided that they are not interpreted literally, but rather in a logical and systematic manner (more recently, Court of Cassation judgment no. 12016 of 19 June 2020), given the possibility, even in such a case, of the use of ambiguous terms which do not correspond to the real intention of the parties.

If, at the end of such an assessment, there are no clear external indications, so that it is not possible to classify the transaction with certainty in terms of a shareholders' loan ....., the results and terminology used in the financial reporting may be taken into account, not only pursuant to Article 2709 of the Civil Code, but also in view of the fact that the same, being subject to approval by the shareholders' meeting, constitutes conduct subsequent to the conclusion of the contract,..... (see Court of Cassation 8 June 2018, judgment no. 15035; Court of Cassation 23 March 2017, judgment no. 7471).

Financial reporting ratios and cash flows: impact of incorrect recognition of shareholder loans (loans instead of capital reserves or capital reserves instead of corporate debt) Hopwood, 1987; Hopwood & Miller, 1994; Hopwood, 1999; Hopwood, 1983; Hopwood, 1990; Hopwood, 2000; Hopwood, 2007).

Ratios

In the preceding pages we have outlined the characteristics of shareholders' loans as loans and thus as debts of the company and shareholders' loans as increases in share capital and thus as reserves to be included in the company's equity. In outlining the special characteristics of the two forms of shareholder financing, we have fully understood the enormous difference that can be identified between shareholder financing as loans and thus corporate debt and shareholder financing as equity. We have already pointed out that such behaviour is unacceptable because the financial reporting resulting from such an entry is untrue and invalid. It should note that the incorrect voluntary recognition of shareholders' loans impacts, sometimes not indifferent, the analysis of financial reporting subject to incorrect recognition (Hopwood, 1976). Financial reporting analysis is carried out through the complementary use of two instruments: ratios and cash flows. It is evident how the inaccurate recording of loans from shareholders impacts the analysis of financial reporting, which, due to incorrect recording, is not true and not correct. In the following, we will highlight ratios that present, at the numerator or denominator, the balance sheet aggregates reclassified according to the financial criterion that includes shareholders' loans payable and equity, which, in turn, contains shareholders' loans on capital account. The incorrect recognition of shareholders' loans directly impacts the ratios that have long-term liabilities and equity at the numerator or denominator. These aggregates take shareholder loans as loans or as equity. Therefore, an incorrect recognition of shareholder loans directly impacts the calculation and, consequently, on the interpretation of the ratios, which include aggregates formed by shareholder loans. All the ratios that we will mention later have this characteristic, and therefore, if shareholders' loans are incorrectly recorded in financial reporting, all the ratios that will be shown in the following pages will be calculated incorrectly and therefore will provide wrong information about the financial or income situation of the company.

Of course, this is not the place to make a detailed analysis of ratios, which we will indicate later. The purpose of this article is only to identify which ratios may be incorrectly calculated as a result of the misstatement of shareholders' loans. Therefore, we will limit ourselves to listing these ratios without going into a detailed analysis of the ratios themselves.

The ratios that will be miscalculated as a result of the incorrect recognition of shareholders' loans, and therefore provide a distorted view of the company's financial and income situation, are the following (Hopwood, 1990):

Lon-term Asset Coverage Ratio

Rationale For The Construction and Management Significance of the Ratio

The long-term asset coverage ratio identifies the ratio used to analyse the long-term financial position.

Long-term equilibrium is guaranteed if the sources maturing beyond the year being closed have an amount that is "compatible" with the total uses with similar characteristics.

The comparison to analyse the long-term financial situation requires that the amount of long-term assets be set against the total long-term sources or the sum of long-term liabilities + shareholders' equity (Hopwood et al., 2007).

From comparing the absolute values of the above aggregates, the so-called structure margin is determined, which, depending on the hypothesis, may be negative or positive. The presence of a negative structural margin indicates a financial imbalance. In contrast, as will be seen in the following pages, the determination of a positive structural margin shows a situation characterised by substantial consistency between sources and short-term needs.

Since the reclassified financial reporting shows a balance between sources and needs, it is clear that, in the absence of separate items, the availability margin is equivalent to the structure margin in amount and sign. If the structure margin is positive, the company will have a positive availability margin. On the other hand, if the short-term situation is unbalanced and characterised by a negative mark-up, the long-term position will also show a negative mark-up of the same amount. These considerations do not apply in the presence of separate debit or credit items. Suppose stand-alone items appear in either section of the reclassified balance sheet. In that case, the financial reporting balance is also guaranteed by the amount of these items, with the consequence that the sum of current assets + long-term assets does not equal total current liabilities + long-term liabilities + shareholders' equity. In such circumstances, the availability margin cannot be the same as the structure margin.

This comparison shows whether the long-term requirements balance the sources with the same maturity characteristics (Hopwood et al., 2007).

Logic of Construction and Significance

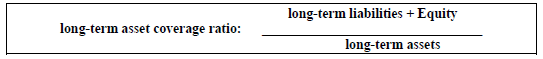

Also in the analysis of the long-term financial situation, the development of a quotient is preferred to comparisons of absolute values to facilitate the interpretation of the data. The so-called long-term asset coverage ratio monitors the long-term static financial balance. This ratio, identified by the ratio of long-term liabilities + shareholders' equity to long-term assets, shows which part of the long-term assets has been financed by sources with maturity characteristics similar to the needs covered (Hoogendoorn, 1996).

The ratio must always be higher than unity because a value lower than 1 implies that the long-term assets have been financed by short-term sources, which is a sign of clear imbalance from a financial point of view. The optimal ratio should reach a value of about 1.25. If, however, the ratio exceeds unity, the company can be considered balanced.

As far as the judgement of the indicator trend is concerned, it can be said that an increase is always positive. At the same time, it can only negatively judge a quotient reduction if the indicator's value falls below unity. In the event of a downward trend, but with an index more significant than one, the judgement on the long-term financial situation remains positive even if a "reduction in positivity" may be noted (Jiang et al., 2021).

Benchmarks

The above states that long-term financial equilibrium is guaranteed if the long-term asset coverage ratio is greater than or equal to one (Lamb et al., 2005).

Judgement of Index Performance

In general terms, it can say that if the ratio increases, the long-term financial equilibrium is strengthened; if, on the other hand, the ratio shows a decrease, the financial situation becomes negative only if the ratio falls below unity. If the ratio dips below unity, the financial situation becomes negative only if the ratio falls below unity.

§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§

Logic of Construction and Management Significance of the Ratio

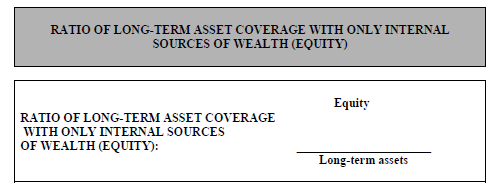

The index of the coverage of long-term assets with internal means of a company's wealth identifies the ratio with which it is intended to investigate which part of the long-term assets has been financed with equity (Lamb et al., 1998).

This ratio is intended to monitor the partial long-term balance, i.e. it refers exclusively to the consistency between the amount of long-term requirements and the total of sources with similar maturity characteristics identifying the company's wealth.

This "balance" is monitored by contrasting equity with long-term assets. In the writer's opinion, even if this ratio shows to be a widespread object of calculation in various information systems, the determination of such a value can be counter-productive. Indeed, one sometimes reads that the ratio analysed here helps assess long-term equilibrium. Such a statement is wrong and misleading. To think that a company can finance all its long-term investments exclusively with equity items seems a limiting assumption that automatically excludes the usefulness of long-term sources such as loans, bonds, etc.

There is no need to detail to understand how this statement must be rejected and, consequently, how the index analysed here, if not correctly interpreted, can lead to incorrect judgements (Hopwood, 2009).

Nothing else can be deduced from the interpretation of this ratio. In general, it can state that the contrast between equity and long-term assets can only and exclusively provide information on the portion of long-term investments financed from the company's sources. For this reason, it is considered that the index of long-term asset coverage with only internal sources of wealth of the company. For this reason, it is considered that the long-term asset coverage ratio with only sources of wealth within the company is of minimal use in analysing the financial situation of companies (Hopwood, 2009).

Reference Parameters

From what has been said above, it can affirm that it is not possible to identify any reference parameter to analyse the companies' financial situation.

Judgement Index Trend

In general terms, it can state that an increase in the ratio indicates an increase in the portion of long-term loans financed from the company's sources. A decrease in the ratio shows a decrease in that proportion. In both cases, it is not possible to express a definitive judgement on the financial/equity situation of the company on the mere basis of the ratio.e dell’interpretazione di questo ratio (Lewis et al., 2009).

§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§

Logic of Construction and Management Meaning of Ratios

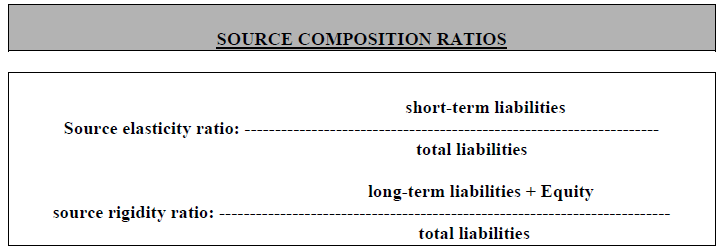

As we have already seen concerning the ratios of the composition of the invested capital, it is possible to carry out similar reasoning concerning the liabilities side of the balance sheet reclassified according to the financial criterion: in this regard, it is possible to determine the elasticity ratio and the rigidity index of the liabilities (Hopwood, 2008).

The liability elasticity ratio compares short-term liabilities with total liabilities, including stand-alone items. In contrast, the liability rigidity ratio takes the sum of long-term liabilities and equity as the numerator and total liabilities as the denominator.

A source structure favours a certain rigidity of sources implies a situation in which the enterprise can enjoy a greater availability of money deriving from the granting of loans that will be repaid in the medium to long term to cover the needs generated operations. On the other hand, an elastic liability structure could lead to situations where cash asynchronies occur if income does not match expenditure at a given time. These indicators, which can also determine in percentage terms, are of little use if they are not set against the composition of assets. For this reason, the writer believes they have a limited possibility of service within the integrated system of business analysis/programming (Kleven et al., 2016).

Benchmarks

There are no standard reference parameters for the two ratios. As pointed out above, must develop every consideration by interpreting, at the same time, the composition of the assets (Markle, 2016).

Opinion on The Trend of Ratios

Based on the considerations made in the above (benchmarks), it is understandable that one cannot associate a positive or negative judgement to specific performance of the source composition ratios. Each consideration must be developed bearing in mind the particular company situation, the trend of the various ratios and, above all, the composition of the assets.

§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§

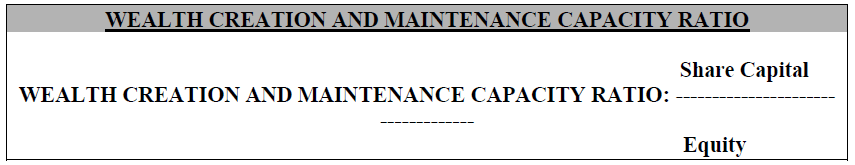

Rationale for the Construction and Management Significance of the Index

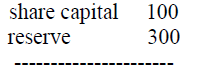

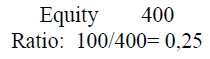

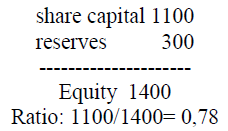

The analysed index shows the weight of the share capital within the net equity. The consideration of the amount of this ratio shows the degree of ability of the company to strengthen its capitalisation through the creation of new wealth with the consequent allocation of the same to reserves. In fact, the ratio measures the existing proportion between the amount of share capital and total equity (Mouritsen & Kreiner, 2016).

The lower the ratio, the more significant the gap between share capital and total equity. This gap can only be due to the presence of reserves - capital or profit - and income from the year-end. The existence of high reserves indicates the ability of the company to create new wealth over time through the formation of profits and the ex-Novo creation of capital wealth and to maintain this potential within the company. The mere creation of new wealth, if not held within the company by setting aside and not distributing reserves, has no impact on the quotient since the achievement of profits without subsequent setting aside and the recognition of capital reserves with the subsequent immediate distribution of the same, do not increase shareholders' equity (Nobes, 1979).

The presence of a high discrepancy between the two values is, therefore, related to the ability of the company not only to create new wealth but also to maintain it within the company economy (Nobes, 1980).

The index assumes a value of 1 when there is a perfect coincidence between share capital and equity. If this is the case, it is clear that no money has been set aside for reserves, which means, among other things, that the capital is not protected against erosion by operating losses (Nobes & Aisbitt, 2001).

On the other hand, if the ratio is greater than 1, this indicates a situation in which losses have already attacked the share capital. This symptom demonstrates the existence of a pathological management situation that has already entered the bankruptcy phase.

A company that, on the contrary, shows an index that is much lower than one which, over time, decreases further, instead highlights a situation in which the capitalisation of the company shows a favourable increase (Nobes & Schwencke, 2006).

However, the study of this indicator must be meticulous as changes in this indicator may depend on several causes. Consider, for example, the case in which there is a transfer of reserves to share capital: this operation has the impact of increasing the index and could be interpreted as an adverse event. However, in substance, this operation (all other things being equal) is entirely neutral since there is no real change in the composition of the assets. Or, suppose that, in a given year, it makes a considerable increase in share capital to increase the company's capitalisation. To understand the impact of this operation, consider the following case (Nobes & Schwencke, 2006):

If an increase in share capital of 1,000 was made, the values would be changed as follows (Nobes et al., 2010; Nobes 2013; Nobes, 2016; Nobes & Parker, 2016):

It is evident that an increase in this index, connected to the greater weight, in proportional terms, of the share capital concerning the total net assets, does not depend on the lesser capacity to maintain within the company new wealth created but is connected to the operation of increasing the share capital. It can only evaluate this latter circumstance positively as it improves the direct capitalisation of the company. This simple example shows how the interpretation of the index is not as immediate as it might seem at a superficial analysis (Oderlheide, 2001).

Benchmarks

The minimum level of the soundness of the share capital is guaranteed when the index is equal to 1, i.e. when the net worth is represented by the share capital only. To guarantee the solidity of the share capital, the ratio should always assume values lower than unity. Apart from this consideration, it is impossible to identify benchmarks to ascertain the existence of possible balances related to net assets (Provasoli & Mazzola, 2007).

Assessment of Index Performance

The considerations made in the previous points make it clear that it is dangerous to associate a "standard" judgment to a specific index trend. Therefore, the writer believes that it is more appropriate not to correlate particular conclusions to a specific ratio direction to avoid incorrect and misleading interpretations (Rocchi, 1996).

§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§

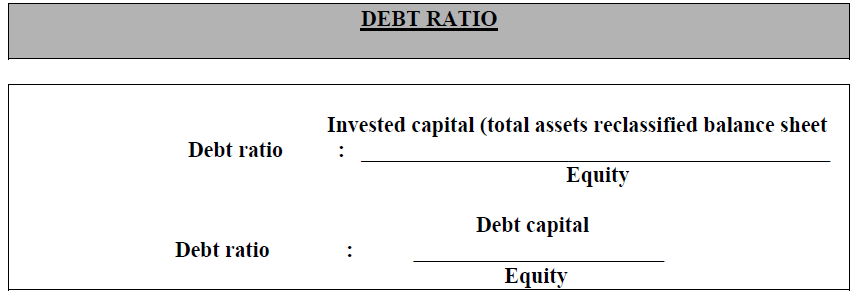

Logic of Construction and Management Meaning of The Ratio

It must monitor the overall financial equilibrium of a company through the use of a ratio that highlights the relationship between the company's wealth and total debt. This ratio is called the "debt ratio" because, directly or indirectly (depending on the formula used), it highlights the proportion between the company's debts and equity. The debt ratio can take on various "formulations".

This paper will limit ourselves to highlighting the two most common formulas. A first determination of the debt ratio can be found by relating total invested capital to equity. Since the invested capital can only be financed by equity or debt, the denominator of this ratio indirectly shows the company's degree of indebtedness (Shaviro, 2008). To ensure balanced financial reporting, a low net worth implies high debts while, on the contrary, high net worth is compatible with low debts. There is no accurate benchmark for this index. If the indicator is around 4, it is possible to say that financial equilibrium is usually guaranteed. Higher values, however, have to be interpreted in light of the intertemporal trend of the ratio, which shows the development of debt over several years. A second formulation of the ratio, which is more straightforward but less widely used, involves the contrast between total corporate debt (arising from the sum of short-term and long-term liabilities) and equity. From the analysis of this ratio, it is evident how its value is related to the company's financial health. A high ratio implies a sizeable relative amount (compared to the net worth) of debts. If the indicator is around 3, it is possible to say that financial equilibrium is usually guaranteed.

However, the above parameters should be considered with extreme caution. An analysis of several financial reports shows that there are companies on the market with much higher rates that continue to live and operate despite this. However, there is no doubt that the further one moves away from the values indicated as "benchmarks", the greater the risk of financial default (Spengel, 2003; Schoen, 2004).

A final consideration should be made concerning the hypothesis, which is not very common, that the debt ratio reaches shallow values. Low amounts of debt are often found in small companies and family businesses (including large and medium-sized ones). In such a case, the company's financial situation can always be defined as optimal, even if, in the presence of a too low amount of debt, the company shows an inadequate use of its credit capacity and, consequently, of its ability to develop (Schoen, 2005).

Benchmarks

From the above, it can say that overall financial equilibrium is guaranteed if the debt ratio reaches the following values (Wagenhofer, 2003):

1. if the invested capitale/equity formula is chosen, the ratio should not exceed the value of 4

2. if the debt capital/equity formula is chosen, the ratio should not exceed 3.

In the event of higher values, it is possible to state that the further the index is from the above parameters, the greater the risk of financial default (Wagenhofer, 2006).

Judgment Of Index Performance

In general terms, no judgement, positive or negative, can be made on the mere consideration of the index performance (Wagenhoferb & Göxa, 2009).

§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§

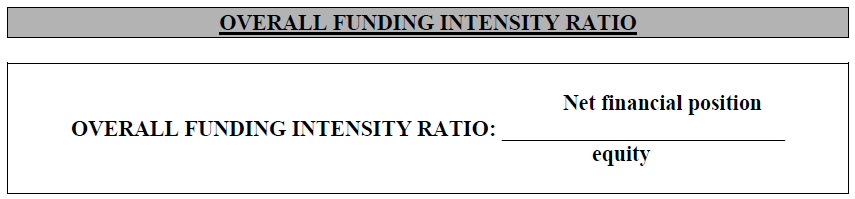

Logic of Construction and Management Meaning of The Index

In this text, we have used the best-known term: total financing intensity ratio. This ratio is part of the set of ratios aimed at assessing the balance between the debt and equity of the company. To have a global view of the financial situation, in addition to the ratios already illustrated above, analysts usually determine the ratio that compares the net financial position and the company's total equity. This indicator takes on various definitions.

To understand the meaning of this ratio, it is necessary to define what is commonly referred to as the net financial position. This margin is derived from the following summation (Zambon, 2002):

1. long-term financial liabilities

2. + short-term financial liabilities

3. - immediate liquidity

4. - readily liquid securities, included in the short or long term assets.

As can be seen, the net financial position, calculated as the difference between financial liabilities (short and long) and immediate liquidity (including immediately liquidate securities), identifies the amount of financial liabilities net of assets that could be liquidated and used quickly for repayment (Zareh Asatryan et al., 2016).

This ratio is widely used in financial analyses carried out by banks because of granting bank credit to companies.

Analysts using this index indicate that the maximum level that the ratio should reach is 2. The presence of higher amounts indicates a not perfectly balanced financial situation that, at least in probabilistic terms, could lead to liquidity tensions.

Benchmarks

Users of this indicator generally assume that the maximum reference value should be 2. Higher values are interpreted as symptoms of potential financial imbalance.

Judgment of Index Performance

In general terms, it can say that if the index decreases, the financial balance strengthens; if, on the other hand, the quotient shows an increase, the financial situation, at least in inter-temporal terms, shows signs of worsening.

§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§

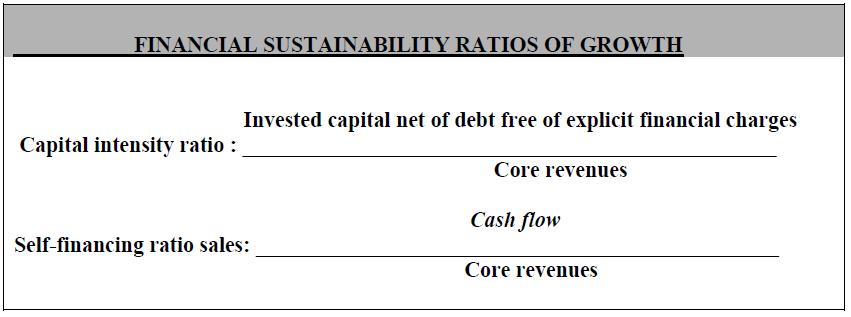

Rationale for The Construction and Management Significance of The Index

The financial sustainability of the company's growth is, in general, monitored through the joint study of two quotients: the capital intensity ratio and the self-financing rate of sales. The former compares the value of invested capital net of all sources without explicit financial charges (e.g. severance pay, tax payables not burdened by interest, various payables not burdened by charges and trade suppliers) and revenues from the company's core business. This ratio measures the capacity of invested capital financed by onerous sources (understood in the sense of financial charges passed through the profit and loss account) to generate typical revenues. The lower the ratio, the greater the ability of the company to exploit the capital for the production of positive income components. The self-financing rate of sales, on the other hand, measures the ability of revenues to create, within the company's economy, cash flows related to the management of typical activities. It is evident that the higher the value of this ratio, the less the company needs to resort to external sources to finance company growth.

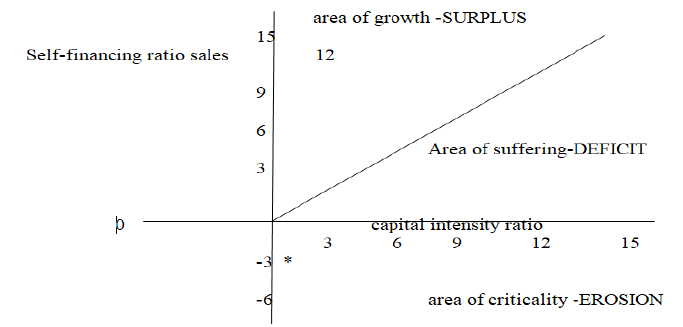

As already mentioned, the two ratios are often interpreted together so that the analyst can monitor the company's ability to self-finance its growth globally. The use and joint interpretation of the two ratios allows the following graph to be constructed:

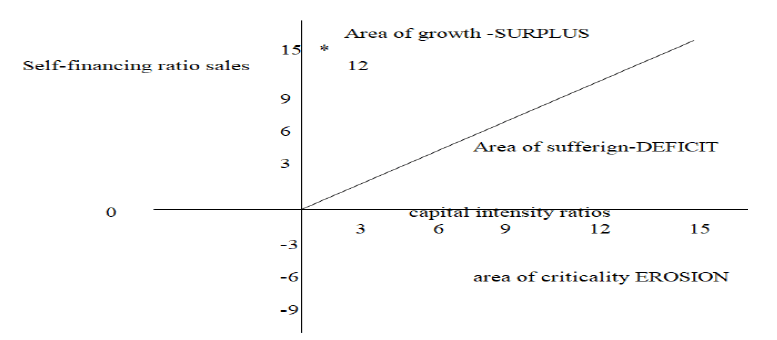

From the analysis of how the above graph is constructed, it is clear that there are three potential areas in which the company can position itself:

Growth-surplus area: area in which the firm shows a high capacity to self-finance its growth. Assume, for example, that the company Alfa is characterised by the following indicators:

1. capital intensity rate: 0.30

2. Self-financing rate of typical revenues: 15%.

On a graphical level, the situation should look like this:

As can be seen, the positioning of the company in the upper part of the growth-surplus area highlights the fact that the company commits, in relative terms, little onerously financed capital and, at the same time, manages to produce a high amount of cash flow. This circumstance allows the company to face high growth in a financially autonomous way.

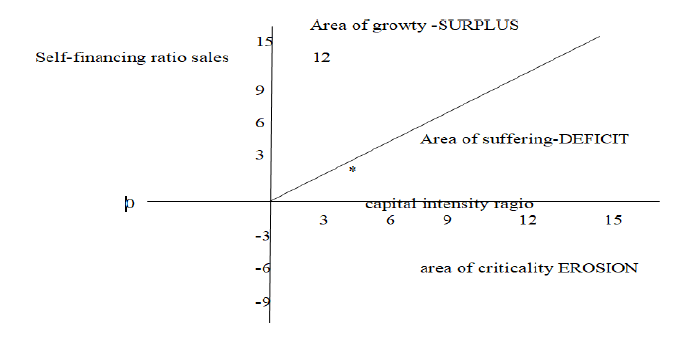

Non-performing-deficit area: an area in which the company does not self-finance its growth with cash flow. The companies in this area show difficulties in self-financing with cash flow produced by the typical management but do not show problems of capital erosion. If the company is established in this sector, it offers a financial difficulty to create internal flows that can guarantee the development of the activity. However, this situation does not yet border on erosion but shows symptoms that should worry the company's management. Assume that company Beta is in this situation:

1. capital intensity rate: 3,80

2. Self-financing rate of revenues: 2%.

The graphic situation would be as follows;

The company is in financial distress, which, in the medium term, may turn into a real financial emergency.

Criticality-erosion area: an area in which the company not only does not self-finance its growth but even finds itself having to erode its capital so that the financial situation does not lead to actual default. Being in this sector causes the company to show clear and severe symptoms of financial difficulties. If the self-financing rate becomes negative, not only does the typical activity not create new financial resources, but it even drains management flows, creating an unsustainable financial situation. The main task of the typical activity is to make money cash flow. When the standard management, instead of creating, destroys monetary resources, it puts the company in a bankruptcy situation that contains the prodromes of a complete financial default within it. Assume that the Delta firm is characterised by the following values:

1. capital intensity rate: 0.5

2. self-financing rate of revenues: - 3%

On a graphical level, the situation should look like this:

No particular comment is needed to understand how management can no longer finance business development and even contribute to draining resources that will divert to other objectives. Even over a short period, such a situation inevitably leads to the company's financial failure.

Benchmarks

No benchmarks are identified for these ratios. The joint interpretation must be carried out in light of the above chart.

§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§§§§-§§§§§§§-§§§

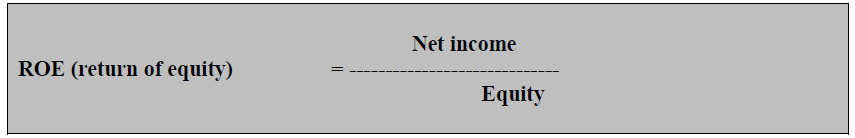

The company's overall profitability analysis is monitored by contrasting net income with equity. The index that allows this analysis is the equity profitability ratio, otherwise known as ROE (Return On Equity).

It should note that the numerator and denominator of the ratio identify the aggregates determined following the management reaggregations of financial reporting. Therefore, the net income does not necessarily coincide with the operating income (due to overhead costs), just as the net management equity may differ from the corresponding statutory value (due to the presence of treasury shares and receivables from shareholders for payments still due).

The analysis of this index allows the evaluation of the company's overall profitability regardless of any distinction between core vs non-core activities and operating vs non-operating activities.

Therefore , the ROE is the most synthetic ratio as it includes all the income elements produced by the company management. The conciseness of this ratio represents, at the same time, the most positive characteristic and the most evident limitation of ROE.

The positive side is that, with a simple index, the analyst can assess the company's overall income performance, which the mere analysis of absolute values could not do. For example, if an increase in the absolute value of the profit for the year of 100% is associated with an increase in the shareholders' equity of 500%, the judgement of the overall profitability of the company would lead to misleading results if it is carried out by considering only the absolute value of the net income. If, on the one hand, the profit shows an increase, on the other hand, this increase, compared to the simultaneous more than proportional increase in net assets, causes a considerable reduction in the company's overall profitability.

The 'limitation' of ROE is the inherent lack of analyticity of the ratio. A positive trend in the profitability of equity does not allow to immediately express a favourable judgement on the income situation of the company as the increase in ROE, even if it is incredibly high, may depend exclusively on non-typical factors of an occasional nature.

For example, if a company shows an increase in the profitability of its net assets due to a high capital gain and the presence of worsening characteristic profitability. The coexistence of characteristic profitability characterised by a negative trend and of overall business profitability that, on the contrary, shows an increase, even a conspicuous one, does not allow a favourable judgement on the company's situation.

For the income situation of a company to be considered favourable overall, it must be characterised by a good performance of its core business. The company cannot base the production of income on extemporaneous, occasional or extraordinary elements. Of course, if such factors were to materialise, the company can only hope to recurrence such positive income components.

However, the economy of a company cannot be based on such elements because, inevitably, if such a circumstance were to occur, the company would be destined to fail. After all, profitability would find its lifeblood in distinctive elements whose frequency is necessarily limited in time. Therefore, the conciseness of the ROE obliges the analyst to develop further insights into the company's profitability to highlight the performance of each component of the company's economy. Like any profitability index, the overall company profitability shows a positive trend in case of an increase of the index and, consequently, a negative trend in case of a decrease of the quotient.

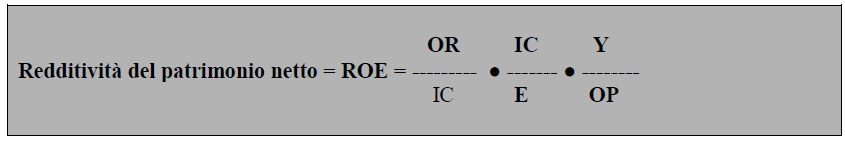

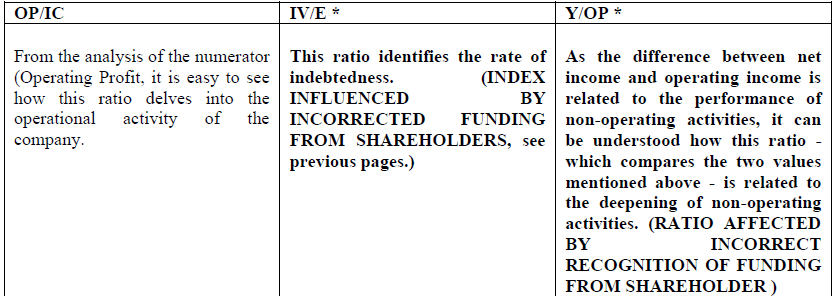

Legenda:

OP: operating profit

IVI: invested capital

E: equity

Y: net income

The possibility of simplifying invested capital and operating income shows how the above formula identifies a mathematically correct economic concept.

Considering the ratios, it is possible to draw these initial considerations:

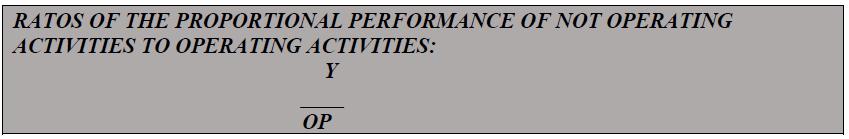

This ratio identifies the proportional "weight" of non-operating activities with respect to operating activities.

Cash Flow Statement

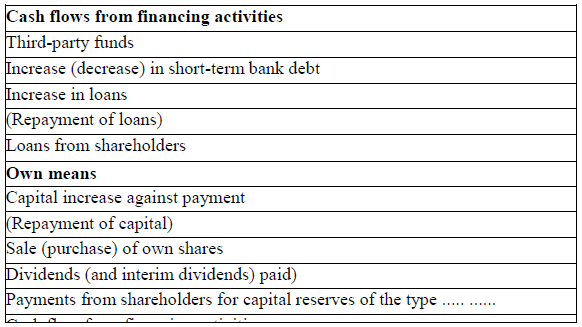

Also with regard to the cash flow statement, the erroneous registration of a loan from shareholders among debts, when, in substance, it is part of equity, or in equity when, in reality, it is a mere debt, causes drafting errors with consequent problems of interpretation of the real company situation. It is well known that the cash flow statement can have various structures according to the legislation we consider or according to the accounting principles analysed. However, it is possible to affirm that, despite the differences that can be found in the global structure, the part concerning financing is similar in all the cash flow statement schemes.

The part concerning this issue generally requires the following information:

As can be seen, the fact that shareholders' loans are incorrectly recorded concerning the substance of the transaction that the company and the shareholder want to carry out has implications for the figures in the cash flow statement. Equity and borrowings are offset against the substance of the values in the company.

It can therefore be stated that also concerning the preparation of the cash flow statement, the erroneous entry of shareholders' loans among debts when they are part of equity, or as equity when, on the contrary, they are intrinsically debts, causes the indication of wrong items in the items composing the cash flow statement. The erroneous inclusion of shareholders' loans also has consequences on the preparation of the cash flow statement as it happens for multiple ratios.

Conclusions