Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 3S

On the Reasons for Slow Growth of Women Entrepreneurial Initiatives in the MSMe Sector in the Backdrop of Policy Perspectives in India

Vijayalakshmi Iyengar, Lal Bahadur Shastri Institute of Management New Delhi

Citation Information: Iyengar, V. (2024). “On the reasons for slow growth of women entrepreneurial initiatives in the msme sector in the backdrop of policy perspectives in india. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(S3), 1-17.

Abstract

Purpose Women entrepreneurship in India has substantial scope to contribute to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country and women employment. The ratio of female compared to male entrepreneurs is observed to be low. In Micro Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), the women entrepreneurs who are rich and affluent are able to progress substantially compared to those who lack education, awareness and economic support. Every year, the Government of India coins new tag lines focusing on woman power such as Nari Shakti, Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, Atma Nirbhar Bharat, Women led Development etc., in addition to launching special financial schemes to support their entrepreneurial initiatives. Despite these attempts, entrepreneurial initiatives undertaken by women, especially those belonging to weaker economic sections is low and less impactful. The objective of the present study is to investigate the reasons for slow growth in women entrepreneurial initiatives in the MSME sector in India, keeping policy perspectives in the backdrop. Methodology The present study is exploratory in nature conducted in six phases. Women entrepreneurs from diverse fields doing micro business have been included in the present study. Convenience sampling has been used. 20 MSME units have been covered and women entrepreneurs running them especially from non-affluent status have been selected. Responses were collected through open ended questions with broad focus on their socio-economic status, associated issues, and reasons for slow growth in their initiatives. Content Analysis was used to analyze the data. The governmental schemes and policies have been analyzed and the responses of the interviewees have been corroborated to bring out the results and conclusions. Findings Six themes emerged from the policy perspective at the end of the study- Policy asymmetry & overlap, Policy Unschooling, Policy shut down, Policy ambiguity, Policy network and Policy digitization. The study is relevant as women are an integral part of the development process of the country and despite a financial ecosystem to support them the impact on entrepreneurial initiatives is not so significant. Shifting the skill set, mind set and tool sets of the women entrepreneurs in India for growth in initiatives is new paradigm brought out in the present study. Paradigm shift from conventional training mechanisms to unconventional mechanisms in the areas of technology such as use of Apps, smart phones and laptops, training on life skills, management skills and industry competencies are areas where future training focus should be concentrated. Teaching life skills and technology solutions are crucial to success of ventures. Addressing the conflicting perceptions between lending and borrowing entities on issues relating to documentation adequacy, eligibility criteria, social and emotional considerations, remote access training, training to stay ahead of the information curve have emerged as criteria that influences the growth of women entrepreneurial initiatives. The inclusion of venture capitalists as financial, managerial and technical facilitators in coaching and hand holding women from conception to launch phase is a new line of thought as against conventional lenders. Research Limitations The limitation of the study is convenience sampling and conducted in the state of Maharashtra. This study can be extended to other states of the country to enhance the robustness of the study and if MSME data is adequately supported by credible data, across each state, on ministerial websites better insights can be obtained. Originality This work brings to fore the need for a transformed nature of training within system of women entrepreneurial ventures focusing on technology tools for providing training, developing skills, and access to information. All the dimensions of the policy factor that inhibits women initiatives have been analyzed in detail. Shifting the skill set, mind set and tool sets of the women entrepreneurs in India with the use of robust technology for growth in initiatives is a new paradigm and distinct contribution. Policy makers and administrators can develop new training models based on new technology tools like ChatGpt to illuminate the women. Teaching life skills and technology solutions are crucial to success of ventures. Women are not limiting themselves only due to funds crunch, they have exhibited the strong desire to be heard, understood and be emotionally facilitated with dignity. One stop hub-portal and its conceptual working model that networks women across states in the country and assists them in taking well informed decisions, based on information presented therein, is a unique contribution to literature. This proposed model could ease out the blocks inhibiting the growth of women entrepreneurial initiatives.

Keywords

MSME, Women Entrepreneurs, Entrepreneurships, Government Policy, Policy Paralysis, Socio-economic women status.

Introduction

The MSME sector is a nursery of entrepreneurship, often driven by individual creativity and innovation. This sector contributes 8 per cent of the country's GDP (Annual report MSME 2022). India is a growth-led economy making a significant impact on the global stage and a portion of it attributable to MSME and successful start-ups that have become unicorns in a short period of time. Their par-taking roles as entrepreneurs, managers, CEOs, tech experts, flight officers as against their male counterparts, permeating through every sphere of activity: economic, social, cultural to establish their prowess. In the recent years, women have emerged as an influencing change agent contributing significantly to the GDP of the economy. India, has passed the women reservation bill in the parliament, recognizing them as a part of the parliamentary democratic process with and through vibrant sloganeering such as Nari Shakti, Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, Atma Nirbhar Bharat, Women led Development DeTienne & Chandler (2007) Tables 1-3.

| Table 1 Percentage Share of Male/Female in Micro, Small and Medium Sector | |||

| Category | Male | Female | All |

| Micro | 79.56 | 20.44 | 100 |

| Small | 94.74 | 5.26 | 100 |

| Medium | 97.33 | 2.67 | 100 |

| All | 79.63 | 20.37 | 100 |

| Table 2 Sector Wise Distribution Among Males and Females in MSMES | |||

| Sector | Male | Female | All |

| Rural | 77.76 | 22.24 | 100 |

| Urban | 81.58 | 18.42 | 100 |

| All | 79.63 | 20.37 | 100 |

| Table 3 Representation of Schemes/Programs for Women Entrepreneurs by Banks and Government | ||||||||

| SN | SCHEME | SUB SCHEMES | YEAR OF LAUNCH | TARGET AUDIENCE | OBJECTIVE/ SCOPE | AGE GROUP | SUPPORT | LIMIT |

| 1 | Bhartiya Mahila Bank (Defunct on )- 2017 | BMB Annapurna Loan – Food Catering |

2013 | Women to establish food catering unit for selling tiffin/lunch packs | Funding for skills developments to help in economic activity | 18- 60 years |

Monetary | ₹ 20 Cr |

| BMB Sringaar | Assist women for Beauty Parlour /Saloon/Spa | 20-60 years |

Monetary | ₹ 20 Cr | ||||

| BMB SME Easy |

Combo of working capital and term loan for Women Entrepreneurs | max 60 years |

Monetary | ₹ 20 Cr | ||||

| BMB Parvarish |

Assist women to establish child day care centre | 21-55 years |

Monetary | ₹ 20 Cr | ||||

| 2 | Mudra Bank | Shishu Kishor Tarun (to signify the stage of growth) | 2015 | Small manufacturing unit Shopkeepers Fruit and vegetable vendors Artisans |

Catering to the needs of the Non–Corporate Small Business Sector (NCSB) segment or the informal sector for bringing them in the mainstream | Monetary | ₹10 lacs | |

| 3 | Central Bank of India | Cent Kalyani Scheme | 2013 | Women entrepreneurs in MSME sector (as defined under MSME Act-2016) | To encourage Women entrepreneurs to start E W projects or expand/modernize the existing project. (Retail trade/Education and training Institute/Self-help group not eligible). |

Monetary | ₹ 100 Lacs | |

| 4 | Punjab National Bank | PNB Mahila Samridhi Yojna | NA | Boutiques, beauty parlours, cyber cafes, Xerox stores, telephone booths, etc. | To provide financial assistance to women entrepreneurs in tiny /Small scale sector and rehabilitation of viable sick SSI units |

Monetary | ||

| PNB Mahila Udyam Nidhi Yojna | NA | Aims to reduce the gap in equity, helping women set up new ventures in the small-scale sector | Monetary | |||||

| Scheme For Financing Creches | NA | Women working for creches | Working women Creche for children | Monetary | ||||

| PNB Kalyani Card Scheme | NA | Individuals, farmers, landless labourers, agricultural labourers, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, lessee farmers, etc. |

Working capital credit requirement of allied agricultural activities/ miscellaneous farm/non- farm activities either singly or in combination with other activities | 18+ | Monetary | ₹ 50,000 | ||

| PNB Mahila Sashaktikaran Abhiyan | NA | Provides credit to women who intend to establish small and micro enterprises in the non-farm sector, offering fee waiver and lower interest rate. | Monetary | |||||

| 5 | State Bank of Mysore | Annapurna Scheme | NA | Women entrepreneurs who are setting up food catering industry in order to sell packed meals, snacks, etc. | Monetary | ₹50,000 | ||

| 6 | State Bank of India | Stree Shakti Package | NA | Women who have 50% share in the ownership of a firm or business and have taken part in the state agencies run Entrepreneurship Development Programmes (EDP). | Aimed at supporting entrepreneurship among women by providing certain concessions | NA | Monetary | Rs.1 crore |

| 7 | Dena Bank | Dena Shakti | 2008 | 1. Agriculture and allied activities 2. Small Enterprises (Direct and Indirect Finance) Micro and small (manufacturing) enterprises Micro and small (service) enterprises which include small road and water transport operators, small business professional and self-employed and all other service enterprises 3. Retail Trade 4. Micro Credit Education 6. Housing |

To promote female owned businesses by providing financial assistance | Monetary | ₹ 20 lac | |

| 8 | Punjab and Sind Bank` | Udyogini Scheme | NA | Women enterprises consisting of all units managed by one or more women entrepreneurs in proprietary concern or in which she/they individually or jointly have a share capital of not less than 51% as partners/shareholders /directors of private limited company/members of co- operative society |

To encourage the women entrepreneurs to avail the loans on liberal terms and exclusive catering of credit. Direct agriculture activities, Tiny SSI sector, Business enterprises, Retail traders, Professional and Self-employed etc. | 18- 45 yrs |

Monetary | Depends on case-to-case basis |

| 9 | Karnatak a State Women Develop ment Corporati on | Udyogini Scheme | NA | Discourages women going to private money lenders or other financial institutions for loan with high interest rate. | 18- 45 years |

Monetary, skill development | ||

| 10 | TREAD | Trade Related Entrepreneurs hip Assistance and Development | NA | Credit will be made available to women applicants through NGOs who would be capable of handling funds in an appropriate manner. These NGOs will not only handle the disbursement of such loans needed by women but would also provide them adequate counseling, training and Assistance in developing markets. | Monetary, Financial Development | Government Grant up to 30% of the total project cost as appraised by lending institutions which would finance the remaining 70% | ||

| 11 | STEP By Ministry of Women and Child Development |

Support for Training and Employment Program of Women | 1986 | Available in any sector for imparting skills related to employability and entrepreneurship, including but not limited to the Agriculture, Horticulture, Food Processing, Handlooms, Tailoring, Stitching, Embroidery, Zari etc, Handicrafts, Computer and IT enable services along with soft skills and skills for the work place | To provide competencies and skill that enable women to become self- employed/entrepreneurs |

16+ | Skills, Training | - |

| such as spoken English, Gems and Jewellery, Travel and Tourism, Hospitality. | ||||||||

| 12 | Small Industry Services Institute. | NA | Provides a comprehensive range of services to the small sale industrial sector in Tamil Nadu in terms of technical assistance, Economic information services, provision of workshop facilities, training and other general consultancy services. |

|||||

“The term MSME as defined by Ministry of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises which has come to effect from 1st July 2020 states that Micro manufacturing and services units shall have an investment of 1 Crore Rupees and capped at 5 Crore of turnover while the small units shall invest up to 10 Crores of Rupees and up to 50 Crores of turnover while the limit of medium units would be 50 Crores of investment and 250 Crores of turnover. Also, a new composite formula of classification for manufacturing and service units has been notified. Now, there will be no difference between manufacturing and service sectors. Also, a new criterion of turnover is added. Particularly, the provision of excluding the exports from counting of turnover will encourage the MSMEs to export more and more without fearing to lose the benefits of a MSME unit. This is expected to exponentially add to exports from the country leading to more growth and economic activity and creation of jobs. The new definition will pave way for strengthening and growth of the MSMEs.” (www.msme.gov.in).

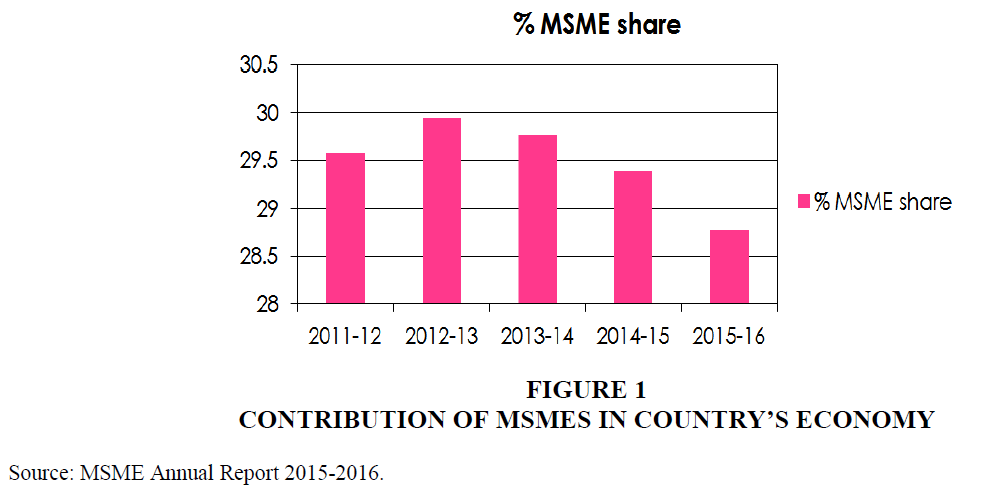

The contribution of MSMEs in the country’s economy has been constant, ranging between 28.75%-29.75%, even between 2012-2016. This situation did not improve much in 2020-2021. As per the MSME annual report of 2020-2021, (https://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/MSME-ANNUAL-REPORT-ENGLISH%202020-21.pdf), the total proportion of women business owners contributing to the total MSME sector, constitutes 20.37% as against men who share 79.63%. Women in micro enterprises contribute 22.24 %, while a meager 5.26% share comes from small enterprises and an abysmally low participation to the extent of 2.67% comes from women owned micro enterprises. It is also surprising that female entrepreneurs in rural areas are more compared to urban areas. These figures 1-5 trigger curiosity to delve deeper into the reasons attributable to the stunned women entrepreneurial performance. With the changing social and cultural scenario, the policy makers further affirmed the changes by introducing several women entrepreneurship programs both at central as well as state level. It is logical to presume that with changes in policy, financial support systems, narratives, and tag lines, the women entrepreneurial performance should systematically grow. However, this is not the case as observed. The growth of women entrepreneurial initiatives is almost stagnant over the last decade and despite several policy measures there is not much change in the scenario. The objective of the present study is to investigate the reasons for slow growth in women entrepreneurial initiatives in the MSME sector, in the backdrop of policy perspectives in India. The slow growth in women entrepreneurial initiatives have been examined from six policy dimensions – asymmetry & overlap, illiteracy, shut down, ambiguity, network and digitization. The dimensions evolved out of the qualitative open-ended interviews taken from women entrepreneurs belonging to weaker sections of the society Handy et al. (2002); Handy et al. (2007).

Literature Review

There is growing trend in rural-women entrepreneurship indicating a positive impact on society both economically and socially (Tamilami, 2010). Women entrepreneurs have unique competencies such as motivation, goal-prone- leadership (Prema Basargekar, 2007) and their role in economic development of the country is evident (Shobha and Koteshwar 2007) yet negative drivers like lack of employment, low family income, socio-cultural barriers, financial, managerial and technical constraints including product-marketing knowledge, demotivates them from setting up their own businesses (Prema Basargekar, 2007). Several challenges account for slow growth in women entrepreneurial ventures. The importance of ‘missing family and societal support’ while navigating through these challenges came out as an important factor. Gender bias continues to infest entrepreneurial eco system especially when women ask for societal approvals or financial sanctions, concluding that, there is a need for robust policies exclusively coined for women entrepreneurs keeping their socio-economic-cultural compulsions in mind. Lack of awareness and training programs among women entrepreneurs in the small businesses, ineffectiveness of training programs offered by state or central government to push women entrepreneurs (Kumar, 2008), lack of awareness and information to access markets, lack of reliable infrastructure and lack of knowledge about intellectual property protection and its exploitation, delayed funds and credit gaps leading to sick units (Nagesh and Murthy, 2008). However, it was found that existing policies were not enough, and different groups needed to come together to support the MSMEs (Singh and Paliwal 2017). Self-help groups like SEWA (Self-Employed Women’s Association) play a crucial role in assisting women legally while applying for license and permits when self -employed women from economically backward sections on the streets of Delhi, face regulatory challenges. Similarly, between funding provided by non-profit organizations and profitable conventional funding sources, women from lower socioeconomic background were found to get easier funding from NGOs and earn higher returns in the non-profit organizations sector. However, women from different socioeconomic classes face different challenges in profit and non-profit sectors. While women entrepreneurs are industrious and motivated, the government, non-government and regulatory agencies need to come together for their development. Government policies do not cover the implementation and success of the policies (Shahdeo, 2015). Developing competitive business strategies such as use of new technologies, e-cluster model with fast credit policies would assist in the growth of the sector. Despite potential, the MSME sector confronts multiple challenges while working closely with the government to create suitable policies could assist their sectoral growth at a quick pace Gupta et al. (2005).

There is also a growing literature on woman entrepreneurship (Minniti 2010; Kobeissi 2010) especially in India (Ghani et al. 2014), attempting to identify factors more definite to growth of woman entrepreneurship. India is aggressively aspiring to become a global superpower and women are integral to making the country wealthier however the impact on entrepreneurial initiatives is not visibly significant. The present study is a narration of true stories that sheds light on the gaps continuing to exist in our ecosystem, especially the schemes of credit assistance, that are meant for economically weaker women led MSME sector. The present study attempts to investigate the reasons for slow growth in women entrepreneurial initiatives in the MSME sector in India keeping policy perspectives in the backdrop.

Methodology

In phase 1, the researchers began conducting open-ended in-depth personal interviews with women entrepreneurs in Mumbai and suburban areas of Mumbai. Convenience sampling was used, and women entrepreneurs from the unorganized sector were selected covering 20 women entrepreneurs owning 20 units. The term ‘economically weaker’ is operationally defined in this study to mean an annual income not exceeding Rs. 8 Lakhs per annum in the entire family. The women were into businesses such as food and masala making, clothing, designing apparels, jewelry, service sectors like beauty clinics & beauty parlour business, candles and designer gifts items, paintings, blouse brocading and stitching, wholesale selling of dress materials, on-line requirement of domestic and auxiliary staff, ayurvedic therapeutic massage services, On- line matrimonial services, On -line and direct classes in cooking and cake making and similar kinds of businesses. These initiatives fall under tiny to micro segment.

Open ended questions were framed on a broad basis, however free- wheeling conversation was encouraged to understand the true sentiments of interviewees. Each interview lasted for 120 minutes of freewheeling discussion, majorly left to individuals to ventilate their thoughts and opinions. Ease in understanding schemes, awareness of schemes, percolation effect, last mile accessibility, sources of information, ease in obtaining funds, collaterals, risk and security, ease of doing business, parallel local hindrances, local approvals, local miscreants were issues on a broad basis, inquired during the interview.

In Phase 2, secondary data were collected from government reports, ministry websites, white papers and annual reports of MSMEs, newspapers, data warehouses like India Stats, CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy), official websites of banks, and lending agencies, etc. to understand the policies and schemes introduced by the government relating to women entrepreneurship. The data collected was analyzed by classifying it according to the scheme and sub scheme, date of introduction, objectives of the policies, target audience / beneficiaries, age limit to avail the loan and amount sanctioned and type of support.

In Phase 3, we corroborated the responses of the women with the schemes and programs available for their entrepreneurial growth. Also, researchers personally visited banks to get data from managers on the frequency at which women visited the banks, inquires, amount dispensed, amount repaid, collaterals, conditions, new and discontinued schemes, successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurial funding schemes. The researchers visited MSME offices to gather information and compared the same with online data available on the bank and government websites Ravi & Roy (2014).

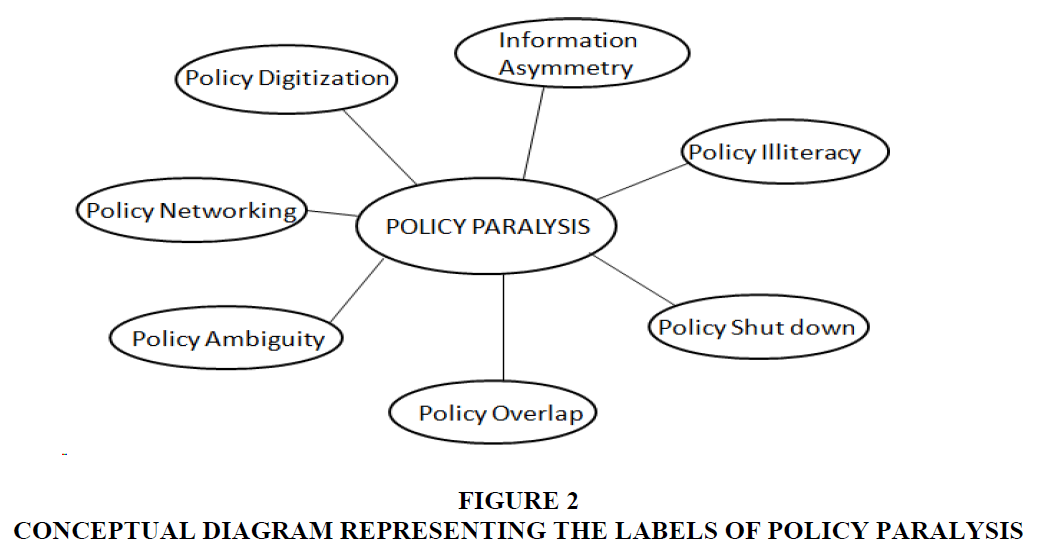

In Phase 4, Open ended freewheeling interview data was classified, and segmented into broad themes, covering financial, marketing, psychological, technical and infrastructural issues. However, in the second round of filtering, all the broad themes indicated leanings towards one single dominant factor which was ‘POLICY’ schemes of the government. Upon content analysis six labels were identified to adequately represent the various dimensions of this ‘POLICY’ factor. These six identified dimensions were - Policy asymmetry & overlap, Policy illiteracy, Policy shut down, Policy ambiguity, Policy network and Policy digitization Mittal & Raman (2021).

In Phase 5, Researchers prescribed a conceptual working-model to make the women entrepreneurial initiatives robust based on the inferences drawn from their interviews.

In Phase 6, Discussions and Conclusions follow.

Analysis of the Interviews and Basis of Label Extraction

‘Policy Factor’ has emerged to be the dominant factor impacting slow progress of women entrepreneurial initiatives. A set of ‘six dimensions’ labelled to policy factor are discussed hereunder.

1. Policy Overlap- Information Asymmetry

Banks are unable to offer all scheme related details (eligibility, documents, business type, target audience, tenure, repayment policy, purpose, operational status etc.) on its web page and most information is overlapping across banks which inhibits objective decision making by the entrepreneur. “I did not apply for loan as the modalities were not explained but I had all government documents, PAN and Rashtriya Swastiya Bima Yojna and bank accounts”. ……government welfare schemes and we don’t have wisdom or risk exposure, so we get confused when many schemes are displayed on multiple websites… and we are unable to decide which scheme is best for us… nobody to tell us…. nobody to inform us on new schemes…..many times websites of the bank give half-baked information and upon visiting the bank we find that the scheme has expired or discontinued…..the ministry website , bank website and google search sites give three different explanation on the same lending schemes with varying details …..” “…. Multiple banks have the same scheme with different names, but we are unable to measure the difference and advantages….” In the RBI report, Sinha (2019) recommended that the lending procedures for the priority sectors (micro and small enterprises) should be uniform across all financial intermediaries. Our study echoes a similar thought. Researchers inferred information asymmetry between scheme details on bank websites versus open-source platforms like Google. This inference has been echoed earlier in field survey conducted by self-help groups and NGOs while addressing issues and challenges of micro level women entrepreneurs. (Edelgive Foundation, 2021). Our study has inferred a similar tone in 2023.

2. Policy Unschooling- Scheme Promotion

Schemes are launched but the right audience has no clue about its nuances. Conventional marketing channels such as Doordarshan, banners, brochures, hoardings, pamphlets, repeated advertisements on paid TV channels, loudspeaker announcements in regional language can create awareness but lacks interpretation. The schemes require to be well positioned for use in the minds of the women. Women approaching financial institutions are found to be declined access to ‘interpretation’ of schemes when they show interest in availing it. “Most times bank managers are not available on the desk to entertain us, and a cordial feeling is missing”. “….probably they are too busy and don’t give us time… “we have language issues and literacy issues”…. …” “……It takes time to understand” “…..bank officials and government are not bringing the information right up to the table of the women in a form understandable to our IQ and literacy level” “…... hidden and latent interest costs are sometimes not disclosed hence we ask the same question in many forms and so officials get irritated…. ask us to come next week…not found on chair….. sometimes deliberately complicate the scheme and discourage us….frequenting to banks is not possible as our daily wages get affected at place of work….” “….we want to be trusted for our competencies.. our repayment is often doubted….we are more committed to return than men ….and often do not ask for more funds than required….”. Schemes become unproductive if they are not articulated enough to the target audience.

It may be pertinent to mention here, while banks articulate schemes to the interested women, they may be unable to pick up the devil that lie in details at a speed required to assimilate it. The researchers conclude that some kind of management expertise, technical expertise and mathematical expertise is necessary before women enter the domain of doing business. While women may have life skills, having industry and professional experience is equally important. This would boost the confidence of lending institutions as most women in tiny and micro-organizations are at best graduates. Hence the schooling of these kinds of expertise requires specialized outcome driven managerial and digital skill enhancements. Such schooling alone may help in giving a confident appeal to the society at large. Even in progressive countries like U.S it was inferred on the same lines as our findings, that men had industry experience, technical expertise (De Tienne and Chandler 2007), were more mature with greater life experiences, which made significant difference on growth of women-led-business in Britain (Cowling and Taylor 2001), hence disadvantaged to choose less profitable sectors with low human capital requirements (Brush and Hisrich, 1991).

3. Policy Shut down- Program Revival

There is no database in public domain that details discontinued schemes. The launch, expiry, discontinuation and revival of bank related schemes are often unknown to women entrepreneurs. Policies shut down within a short period from its date of launch. “……. we go the bank based on the advertisement hoarding displayed outside, but realize the scheme is shut down long back….why are redundant hoardings displayed and they are so misleading!!….it is a waste of our travel time and money…..”. “…..pamphlet and brochure is given in our hands and they ask us to read it and come with all necessary documents….”. For example, Bhartiya Mahila Bank launched by former Prime Minister of India, Shri. Manmohan Singh’s government in 2013, focused on specialized lending to marginalized, discriminated, unbanked, rural and urban women entrepreneurs. However, the bank shut down in just 3 years due to lack of promotion of its existence and intent. Besides, absence of encouragement to women leads to a situation where there are no takers for new schemes, resulting in a premature demise of good schemes. Loan disbursement procedures and responsibility of getting the formalities fulfilled from the borrower seem to be a burden for the loan officers (Kumar et al. 2018). From the interview analysis it comes out that the warmth and reception is missing in the lending institutions, which discourages them from availing any product benefits. The lack of empathy among the loan providers and financiers has been thoroughly discussed by which discourages women from applying for loans and utilizing the benefits of the schemes. This situation is not any different in 2023, when this study is being conducted. Earlier studies in the previous years too, have resonated similar observations.

4. Ambiguity -Program Clarity

Plethora of information available in an unorganized manner creates ambiguity for growing entrepreneurial initiatives.

“…….the terminologies and expressions mentioned in the schemes are often misleading. For example, some of the schemes contain words like self-help groups and some say self-employed groups, which are used interchangeably…..synonymously…… hence create ambiguity”….. “we don’t understand the difference between tiny and micro organizations…..but words and terms are used in similar contexts but they carry a different meaning…..especially with respect to eligibility amounts, moratorium and repayment slabs, penalty charges….. and there are businesses that fall under multiple categories …and different lending institutions have a different criterion for categorization……, we are unable to get clarity while comparing schemes across banks…..which often leads to misconception. “Banks don’t provide us facilitators…. their first question is how will you repay, when will you repay……or see things from our shoes…..” “……we cannot confidently risk our collateral assets as family restrictions are there”. “……nobody to help us make the right choice: low on risk, high on return and businesses that have high probability of success and high chances of failure….….” “………we have the energy, ideas and enthusiasm but nobody to vet our project proposals formally and screen its market potential, and future funds are a problem…..when we arrange through alternative personal sources we can’t scale up as interest rates are very high and we cannot borrow huge amounts….., ….even when we fill up the forms in the bank we need support …… so we need a personal project facilitator who can always be available to address our fears ”.

These pieces of reaction showed lack of confidence, inability to take calculated risk, fear of unknown and dangling threat of bank penalties in an event of non-repayment of borrowings, or mounting interests in a loss-making business. In earlier studies it is established that between opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial enactment there is an element of risk tolerance (Marlow and Carter, 2004) and even in progressive nations, like U.S female entrepreneurs prefer business with a low risk to return ratio (Kepler and Shane, 2007) and hence shy away from non-traditional businesses (Smith-Hunter and Boyd, 2004). The researchers arrive at the conclusion that unconventional confidence boosting measures would help in spurting their initiatives to take bolder steps Tamilmani (2009).

Other studies have supported our findings where constraints such as unreasonable collateral requirements, poor book-keeping of records, high cost of formal credit, complex and lengthy loan procedures; consciously or subconsciously influencing the decision of business owners to repel the idea of formal finance (Watson et al., 2009) which is all the more high in women owners especially in Indian context.

Training is also a factor that can catapult the aspirations of women. The NGOs and district level officers can be roped in to act as trainers, counsellors and facilitators of policy percolation. Probably to infuse confidence and risk appetite are essential ingredients pivotal to the game of women entrepreneurship. The importance of training has been emphasized in a study conducted in Bangladesh. ‘There are no agencies, even not a single special institution in Bangladesh to produce qualified graduates or trained manpower that can serve as entrepreneurs. Basically, to create entrepreneurs no hard and fast facility is required; but for an effective entrepreneurship generation, entrepreneurship education is necessary. (Abdin, 2010)’.

5. Policy Networking (State and Central Government)-Inter State Coordination

There is limited access to networking opportunities among women on board, because there is no ‘one single digital platform’ for these schemes. “Most of the schemes change or are discontinued if the ruling party steps down from power…. Each party highlights the benefits of its schemes while trying to put down the schemes introduced by opposition….:” “The schemes of the government work in tandem only when the state and centre power systems, belong to the same party”. When a policy is launched for women entrepreneurs, State and Central government have divergent views on the execution plan and compete on superiority especially if they belong to different political parties. The importance of integration between supportive organizations, institutions and entities, with and through technology infrastructure, and the need for educational institutions for entrepreneurial training and development has been inferred by Lovely Parvin et al, (2012) in a study on women entrepreneurship challenges in Bangladesh.

6. Policy Digitization- Information, Network, Communication

“……Most information is digital and on computer and we don’t have connection….” Many women are well equipped with mobile service offerings, social media interaction, information mining tools, internet and search vehicles, web based and mobile based downloadable Apps, SMS, direct to home service, notifications etc. The in-depth interviews allow us to suggest that a one-stop shop online platform to compare various government schemes should be made available for the women entrepreneurs. It will help aspiring entrepreneurs to compare the schemes, decide and apply for the most suitable option. For example, policy bazaar.com – an insurance comparison portal, helps the customers to compare the insurance policies and take well informed decision. Such a portal would help the women entrepreneurs across states (rural and urban) to stay well connected through a networking hub to mutually share experiences and resolve their doubts too. Women entrepreneurship is a national goal, as it contributes to the country’s GDP. and hence inter-state policy networking platforms, can result in better outcomes. The importance of vocational, skill- based training in rural pockets has been emphasized by Sharma (2018) where she has inferred that unless ICT related skills are not imparted, the women will be unable to make entrepreneurial progress. Arogya Sakhi (Mobile App for preventive health care at doorstep), Internet Sathi (Internet on bicycles used to train women for 6 months) are programs that have been launched for digitally empowering women through hands on training, yet the ineffectiveness is pronounced (Sharma, 2018).

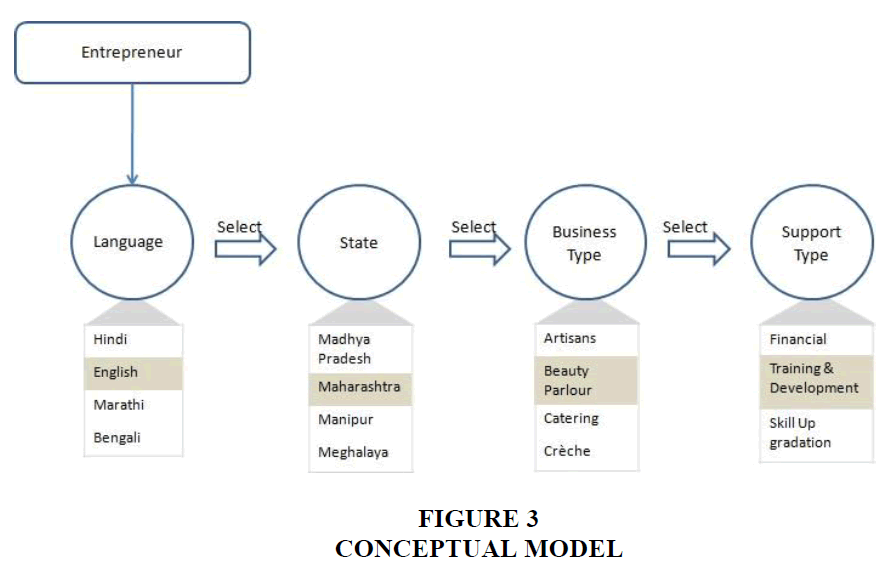

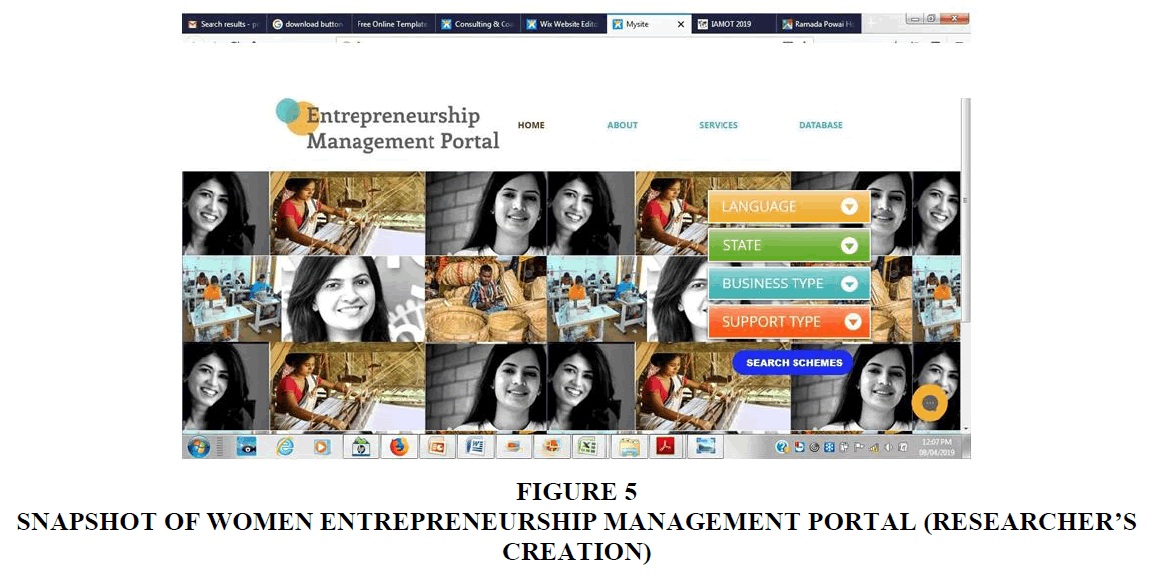

Prescriptive Digital Prototype Model

Researchers have proposed a digital prototype-model which demonstrates the architecture of a one stop information hub portal and its working. The portal provides all information and fresh updates related to women entrepreneurship schemes in MSME sector. The model shows a systematic view of an interactive user interface wherein an aspiring woman entrepreneur can access all the information based on the selected criterion like language, state, business type and support needed (Biswas, 2015).

Step 1: Open the Entrepreneurship Management Portal by visiting the website at www.entrepreneuralmgmtxxx.com and register by name, address and unique national identity.

Step 2: Entrepreneur needs to select the language of her choice from the options available in the language drop down box.

Step 3: Upon language selection, the user will be further presented to select the state of his choice which will provide scheme related details discrete to that state.

Step 4: Next, the user will be prompted to select the business type. This button will provide a drop-down list of all the types of businesses included in the MSME sector for which government funding is available, the limit thereof, documentation necessary including repayment and other collateral conditions.

Step 5: Finally, user needs to select the support type required like financial support, training and development, skill up gradation, risk exposure, terms of lending, legal support, family counselling, regulatory support, etc. and select the search scheme button. At one time a user can select more than one support.

Step 6: On filling the required details the user will obtain a cross comparative consolidated view of all the schemes with specifications entered by her, by the Central and the State government. It becomes a one stop hub for comparison and cross validation of all central and state driven schemes, basis the user requirement.

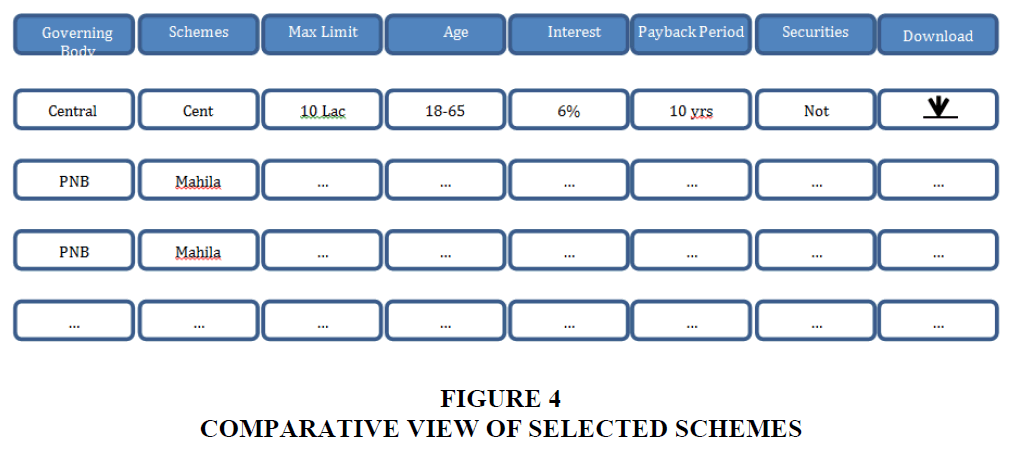

Step 7: Figures 4, 5 complement one another as a conceptual model representing scheme comparisons, and the design of women entrepreneurship portal.

Multilingual Women Entrepreneurship Management Portal depicting Comparative Schemes across States, Business Types and Financial Support Policies of the Government

Discussion and Conclusion

Apparently, it seems that financial constraints are the majorly limiting the possibilities of women initiatives in owned businesses. However, the system lacks resource persons to objectively train entrepreneurs, and assist them in comparing various schemes and counsel them in taking a well- informed decision. COVID has made us understand that remote access can help build work efficiency as much as being on desk for work physically. The business models of training need to change from physical to digital. Training programs for women entrepreneurs needs to switch to remote access instead of a face-to-face training as a wider audience can be addressed. AV recordings of such workshops should be freely accessible for users at any future time for their support. Women entrepreneurs (WE) expect a more humane touch in form of a compassionate facilitator /coach who has trust in their initiatives. They require facilitators in making apt decisions on scheme choices reduce their risk, build positive energy, motivation from the lenders and above all, omni presence whenever needed. SHGs could help in building confidence, clarifying myths and providing emotional support. Government of India approved facilitators could be young graduates searching for employment and they are best suited to travel all over India to articulate the policies, provide digital training on how to effectively put laptops and smart phones to access the required information. Whereas the number of newly started MSMEs is recounted multiple times, there is no data on the ones which closed operations. Furnishing credible and updated information on government portals, websites, and data banks would assist in the growth of women entrepreneurial initiatives as well -informed decisions can be taken. It may also be pertinent to introduce venture capitalists into the system of women entrepreneurial initiatives as they perform a dual role of advising, screening, handholding and stakes funding at the same time. The seriousness of the government would be appreciated if they make an empaneled pool of VCs and entrust them with the responsibility of growing, reviving and sustaining WEI (Women Entrepreneurial Initiatives). The role of VCs has the potential to go beyond start- up funding and stake holding. CSR deliverables for women entrepreneurial initiatives with a defined measurable outcome metrics would assist in showing growth in the MSME sector.

It is well known that MSME sector provides maximum opportunities for both self-employment and jobs. The women enterprises have contributed towards stabilizing income rather than increasing income and employment. Women entrepreneurial initiatives are constrained to grow at a desired speed due to policy related information asymmetry, ambiguity, overlaps, closure, digital and soft skills support.

Theoretical and Practical Contributions

Our contribution seems significant here as previous studies inferred that ‘banks face lending challenges, due to information asymmetry in documents held by borrowers and there is a potential risk in lending to MSME entrepreneurs as they may contribute to mounting NPAs (non-performing assets) for Indian banks. We contradict this view as several women despite holding valid documents have been discouraged from availing funding facilities. The unique contribution of this study would be to address this tussle of perception between MSME lenders and borrowers both of whom claim information asymmetry. There is an expectation mismatch between funding institutions and recipients. Women entrepreneurs not only expect funding; they wish to be heard. This research piece is a case of old problem old solution in some ways like information asymmetry, rural language barriers, hostile temperament of bank officers etc. but is also a case of old problem and new solution as technology is disruptive like never before. Millions of audiences can be trained and addressed in one sitting with latest tech-tools, mobile Apps, courses like Coursera and Udemy, and internet-based AV tools and ChatGPT. We bring to fore the absence of a reliable databank that has reliable information on continuing and shut MSMEs. Our conceptual model on one-stop portal hub that addresses information asymmetry and allows scheme comparison for effective decision making for the literate and digital voice assistance facility on the same portal for illiterate women to strengthen their entrepreneurial motives can initiate some dialogue towards filling this void. Using ICT in several innovative ways is possible with technology disrupting itself as frequently as never before. The policy makers and thought practitioners will be able to take leads from inferences of this study as women- entrepreneur status, issues, and performance is found status quo over the years despite repeated studies conducted at intervals. The limitation of the study is convenience sampling and conducted in the state of Maharashtra. This study can be extended to other states of the country to enhance the robustness of the study and if MSME data is adequately supported by credible data across each state on ministerial websites better insights can be obtained.

References

Biswas, A. (2015). Opportunities and constraints for Indian MSMEs. International Journal of Research, 2(1), 273-282.

Brush, C., & Hisrich, R. D. (1999). Women-owned businesses: why do they matter?. Are small firms important? Their role and impact, 111-127.

Cowling, M., & Taylor, M. (2001). Entrepreneurial women and men: two different species?. Small Business Economics, 16, 167-175.

DeTienne, D. R., & Chandler, G. N. (2007). The role of gender in opportunity identification. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 31(3), 365-386.

Ghani, E., Kerr, W. R., & O'Connell, S. D. (2014). Political reservations and women's entrepreneurship in India. Journal of Development Economics, 108, 138-153.

Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2005). Entrepreneurship and stereotypes: Are entrepreneurs from Mars or from Venus?. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2005, No. 1, pp. C1-C6). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Handy, F., Kassam, M., & Renade, S. (2002). Factors influencing women entrepreneurs of NGOs in India. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 13(2), 139-154.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Handy, F., Ranade, B., & Kassam, M. (2007). To profit or not to profit: Women entrepreneurs in India. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 17(4), 383-401.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kepler, E., & Shane, S. (2007). Are male and female entrepreneurs really that different?. Washington, DC: Office of Advocacy, US Small Business Administration.

Kobeissi, N. (2010). Gender factors and female entrepreneurship: International evidence and policy implications. Journal of international entrepreneurship, 8, 1-35.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kumar et al. (2018) https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/issn/2398-628X

Kumar, A. (2008). Awareness of supporting agencies among women entrepreneurs in small businesses. The ICFAI University Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 5(4), 341-364.

Marlow, S., & Carter, S. (2004). Accounting for change: professional status, gender disadvantage and self?employment. Women in Management Review, 19(1), 5-17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Minniti, M., & Naudé, W. (2010). What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries?. The European Journal of Development Research, 22, 277-293.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mittal, V., & Raman, T. V. (2021). Financing woes: estimating the impact of MSME financing gap on financial structure practices of firm owners. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 11(3), 316-340.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nagesh, P., & Murthy, M. N. (2008). The effectiveness of women entrepreneurship training program: A case study. The ICFAI University Journals of Entrepreneurship Development, 3, 24-40.

Parvin, L., Jinrong, J., & Rahman, M. W. (2012). Women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh: What are the challenges ahead?. African Journal of Business Management, 6(11), 3862.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Prema Basargekar (2007), “Women Entrepreneurs: Challenges Faced”, ICFAI Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 5(4), 6-15

Ravi, R., & Roy, A. (2014). Competitive business strategy for sustainable development of MSME sector in India. Journal of Commerce and Management Thought, 5(2), 306-313.

Shahdeo, L. R. R. N. (2015). Development of Women Entrepreneurship in India. Anusandhanika, 7(1), 122.

Sharma, S. (2018). Emerging dimensions of women entrepreneurship: Developments & obstructions. Economic Affairs, 63(2), 337-346.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, S., & Paliwal, M. (2017). Unleashing the growth potential of Indian MSME sector. Comparative Economic Research. Central and Eastern Europe, 20(2), 35-52.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Smith?Hunter, A. E., & Boyd, R. L. (2004). Applying theories of entrepreneurship to a comparative analysis of white and minority women business owners. Women in Management Review, 19(1), 18-28.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tamilmani, B. (2009). Rural Women Microentrepreneurs: An empirical study on their social profile, business aspects and economic impact. IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 6(2), 7.

Received: 04-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14066; Editor assigned: 05-Oct-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-14066(PQ); Reviewed: 27-Oct-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-14066; Revised: 03-Jan-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14066(R); Published: 08-Feb-2024