Review Article: 2019 Vol: 18 Issue: 1

New Zealand Foreign Direct Investments and Their Economic and Societal Impacts: A Review

Olufemi Muibi Omisakin, Otago Polytechnic Auckland International Campus

Camille Nakhid, Auckland University of Technology

Abstract

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is the act of a resident entity in one economy (country) acquiring a direct investment interest in an enterprise resident in another economy (investee enterprise). The process involves building a bond between the investor and the investee with some degree of management and technological influence on the investee enterprise. The main aim of this relationship is for the investor to help provide needed capital, technology know-how and managerial capabilities to the investee enterprise, aiming to improve the overall position of the business. This study reviews, evaluates and analyses New ZealandâÂÂÂÂs foreign direct investment and its economic and social impacts. While the study discusses FDI from a generic perspective, the analytical perspective focuses on New ZealandâÂÂÂÂs FDI sources, framework, sectorial investment, role, impact and effects on New ZealandâÂÂÂÂs economy and society. It presents a descriptive quantitative and qualitative in-depth analytical review of New ZealandâÂÂÂÂs foreign direct investment and its social and economic implications. While the study concludes that FDI is most beneficial to New ZealandâÂÂÂÂs economy and society, it also highlights the shortcomings of FDI in New Zealand if checks are not made.

Keywords

Investment, Foreign, Inflows, Stock, Resources, Market, Strategic, Capability.

Introduction

Foreign direct investment provides a major stimulus to economic growth and development for both developed and developing countries. Motivational factors for countries adopting FDI could be their inability to source adequate financial and technological resources for growth and development of their domestic economies. The effects of FDI in a given economy include: adding to the available domestic resources for investment and capital formation; enabling technology transfer skills; enhancing the competitive innovative environment for domestic firms; and infusing globally acceptable modern management. FDI can be seen from two perspectives. While FDI flows constitute the value of investments made by foreign investors into another country’s economy, FDI stock represents the value of the share capital and reserves of the parent company and the net indebtedness of the subsidiary company.

This study reviews, evaluates and analyses New Zealand’s foreign direct investment. It aims to define the economic and social implications of FDI. New Zealand is a relatively small country in terms of its population of 4.87 million (Stats NZ, 2018). For this reason, it is difficult for New Zealand to mobilise enough savings to attain needed economic growth and development. Corroborating the author’s view, the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (2016) said: “Given New Zealand’s shallow capital base, much of this will need to come from overseas investors. Simply put, we need more FDI to achieve our economic and social goals.”

New Zealand has benefited immensely from receiving FDI, but this is not to say that it has no shortcomings. I believe New Zealand’s ability to impress the generality of investors to invest in New Zealand is a result of its relative political stability, policy and economic feasibility and its administrative feasibility. While many countries and private investors do invest in New Zealand, this study will not be able to beam its search light on all those involved in investing in New Zealand. The analytical focus will be on investments from Australia, China and the US, the implications of FDI for the economy and society. Appropriate recommendations will be made.

The study is structured as follows: Chapter 1 introduces the study, chapter 2 reviews previous related studies, chapter 3 outlines the method of data collection and analysis while chapter 4 analyses the role, impact and effects of FDI on New Zealand’s economy. Chapter 5 concludes the study and recommendations are made in chapter 6.

Literature Review

Moran (2016) contends that foreign direct investment (FDI) occurs when an investor or business organisation in one country invests into a business operation in another country. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (n.d) summarised FDI as investment made to obtain an interest in business organisations operating outside the economy of the investor and to have a voice in the management and control of the acquired business. The process could be through Greenfield or a wholly owned affiliate, acquisition of local business organisation or joint venture with other business concerns.

FDI flows and stock are used to ascertain the phenomenon of FDI in an economy. FDI flows are described as the amount of investment made by foreign investors in a domestic economy over a period calculated on a yearly basis. However, investment could be ‘inflow or outflow’. Inflow is the direct investment made by a non-resident of the reporting economy while outflow is the direct investment made by investors of the resident domestic economy into another economy. These flows are calculated yearly to arrive at net value.

FDI stock represents the value of share capital and reserves (including net profits) of the parent company and the net indebtedness of the subsidiary company. At country level FDI stock could be inward and outward. Inward FDI stock represents the value of foreign investors' equity in net loans to businesses resident in the reporting economy while outward stock is the value of the resident investors' equity in and net loans to business organisations in foreign economies. The two are measured in USD.

Kokko et al. (1996); Aitken et al. (1997) cited in Scott-Kennel (2007) argued that inward foreign direct investment (FDI) contributes to host country resources productivity, capacity building, acquisition of needed skills and required knowledge by domestic firms. Inward FDI is also associated with importing needed technology which helps in building domestic technological capability. Properly managed inward FID is expected to increase domestic production leading to improvement in exportation. Contrary to this assertion Gunther (2015) pointed out that not all inward FDI are beneficial to the domestic economy particularly from developing or transitional country’s perspectives.

Following up on this Scott-Kennel (2007) researched into Foreign Direct Investment and Local Linkages: An Empirical Investigation relative to New Zealand. The author examined the quantity and quality of FDI relative to transactional and collaborative linkages between FDI firm and domestic firms. The author found only 14% had range of linkages and alliances and 39% seem limited to parade and rivalry effects. Scott- Kennel concluded that linkage between FDI firm and domestic firm is influenced by level of competition, motivation for FDI, level of business activity, technology and ownership percentage. Scott-Kennel (2004) researched into New Zealand FDI. The author found that New Zealand domestic firms having foreign affiliates benefited in the area of finance, product services and technology transfer. This helped in facilitating new innovations to the productive sector and the New Zealand market as a whole. However, while foreign partners enhances domestic partners’ operational competitiveness and technological knowhow, domestic partners were responsible to developing location-bound competencies. Similarly, Iyer et al. (2011) examined Foreign and Domestic Ownership from the perspective of productivity spillovers. The author found foreign owned firms being more productive and export oriented, Export oriented domestic firm appropriate backward and forward spillovers from foreign firms. However, no productivity benefit accrue to domestic firms not engaging in export. From the above literature review it is of the opinion of the authors that inward FDI has some positive spillovers to the domestic firms. However, success and or attractiveness of FDI to countries is subject to some of the following factors: labour skills, size of economy, opportunity for growth, political stability, exchange rate, government trade policy, infrastructural facility.

FDI Theoretic Perspectives

There is no generally accepted theory on FDI. Today, FDI could be argued from an internalisation theory perspective which explains why firms exist, leading to more multinational enterprises. The internalisation theory was developed by Buckley & Casson (1976). The authors used the theory to explain the growth of transnational companies and motivations for FDI. The authors demonstrated how transnational enterprises used their internal activities for specific advantages. However, Hymer (1976) contended that transnational companies might need to make cost adjustments when embarking on FDI.

Theories on FDI could also be discussed from the following theoretical perspectives:

“The product cycle theory was developed by Vernon (1996)”. Vernon used the theory to elucidate the type of foreign direct investment by American businesses in the manufacturing industry in Europe at the end of the Second World War. According to Vernon, American businesses embarked on four stages of production cycle: innovation, growth, maturity and decline. This theory explained that American businesses created new and innovative product in the domestic economy, intending to export it to another country. American businesses were able to do this because of technological advantages over their competitors.

The theory of exchange rates on imperfect capital markets explains the justification for FDI from the perspective of foreign exchange risk. This risk factor constitutes the reason for FDI (Cushman, 1985).

Dunning (1980) Developed the Eclectic Paradigm

This theory is a mix of three different theories on the advantages of direct foreign investments. OLI was used as an abbreviation to explain the advantages derivable from the eclectic theory. “O” represents ownership; “L” represents location while “I” represents internalisation. Advantages resulting from engaging the eclectic theory are:

Monopoly/ownership advantages, which could be in the form of privileged access to markets because the business is the natural owner of natural and limited resources, patents and trademarks. The business could have the benefit of technological know-how, engagement in more innovative activities than its competitors and enjoy economies of scale, learning and access to financial capital. This could lead to ownership advantage leading to engaging in FDI.

Location advantages, which make some countries become destinations for the transnational business activities of most of the transnational corporations. These advantages could include economic benefits such as availability of quantitative and qualitative factors of production, infrastructural facilities to reduce business costs, good telecommunications to enable organisations to communicate effectively with stakeholders and enhance good teamwork, market size and access. The bigger the market is, the greater the profit potential, especially when the business is capable of increasing its share of the market (Disdier & Mayer, 2004). Internalisation advantages are determinant factor for multinationals to either choose to expand internally or sell its rights to expand to other firms. However, irrespective of ‘OLI’ theory, political advantages that enhance good government policies on FDI flows and social advantages such as cultural diversity in the host country and host acceptance of foreigners all increase market share.

According to Dunning (1980), businesses that can demonstrate the two advantages of ownership and location will become profitable which will prompt businesses to go FDI. However, application of the eclectic paradigm OLI may differ from business to business and country to country because it is subject to host countries’ economic, political, domestic business law and social contexts. Moosa (2002) argues that countries will attract FDI if they have growing economies, good educational systems to facilitate research, and low country risk to enhance high return on capital.

Motivation for FDI

Various factors could motivate a given business concern or country to engage in FDI. This study discusses the following as generic factors that may prompt businesses to engage international (FDI):

Resources/material seeking: Businesses could embark on FDI with the intention of seeking needed resources/material from another country. These resources could be natural, such as labour (unskilled or average skilled). This occurs mostly when resources are cheaper than in the home country. The main motivation here is production cost reduction.

Market seeking: Investors and corporate businesses engage in FDI to obtain market share, believing that the bigger the market, the bigger the share of profit, all things being equal. Domestic investment in production of consumer goods and industrial product could necessitate FDI when the domestic market is saturated or domestic competitors are seeking investment abroad. This could lead to investment in production in the regional market or beyond. The choice of country or region will be a result of availability of liberal trade regime, market size, market growth forecast and market share. The researcher sums these up as the main reasons why many businesses continue to invest in China despite the communist political system with a blend of open market.

Production efficiency seeking: Investors seeking FDI via production efficiency are motivated to produce in other countries where production factors are cheaper, especially labour, than in the home country. Barnat (2014) argues that the motivation for FDI for production efficiency is to justify the structure of established resource bases and to gain from common governance of geographically spread activities.

Strategic asset or capability seeking: Businesses seeking FDI through acquisition of assets of foreign corporations do so to promote their long-term strategic objectives. In most cases businesses seeking global or regional presence acquire strategic assets to be competitive in the unknown business environment. In this case the business can purchase assets/buy local business or go into alliance with another local business to achieve its strategic interest. This is done for many reasons among which are: job creation in the foreign country; investment in local capital believed to be insufficient; tax incentives, contribution to economic growth and government revenue income. When the company starts to export, foreign exchange inflow will be enhanced and will stimulate the economy by infusing modern management and technology into the acquired business. Apart from making an investment, the investor/business will create access to global distribution channels. Foreign investment in another country could help stimulate privatisation and restructuring, especially in an underdeveloped and or developing country seeking restructuring.

These results are attainable through expertise, skills, experience, ability to raise capital and capability of raising further investments in the restructured/privatised companies. Often foreign companies in the domestic economy are a source of efficiency improvement in local businesses through access to new technology and diversification of production processes. However, these benefits may not always occur when she FDI is short-term or the investor has ulterior motives.

Methodology

The study used data from Statistics New Zealand and other time series data available with detailed emphasis on New Zealand FDI. From the data collected the study estimated how the determinants of FDI flow into the New Zealand economy. The study identified some explanatory variables to characterise the determinants of FDI flows to New Zealand. Descriptive analysis was done with qualitative discussions to evaluate the quantitative data collected. Analysis focused on the source, sectorial framework, roles, impacts and effects of FDI in New Zealand. From this analysis conclusions were drawn, and recommendations made on what needs to be done to ensure that FDI has no adverse effects on New Zealand.

New Zealand FDI Framework Perspective

According to New Zealand Stats NZ (2017) FDI is a measure of the value of foreign-owned companies operating in New Zealand. Foreign investment has been pivotal in building the New Zealand economy. During the colonial period, foreign investment was as much as 273% of GDP. Investments were more in the agricultural, banking and finance sectors, building construction, railways, ports and other public infrastructure (The Treasury, 2015).

New Zealand’s stock of FDI has been progressive following the economic reforms of the 1980s. However, there has been a tremendous increase in FDI in New Zealand recently. As at 31 March 2017, total foreign investment in New Zealand was $397.8bn increasing to $404.0bn on 30 June 2017. Similarly, equity investment by foreigners in New Zealand reached $110bn on March 31 and assumed a record of $113.2bn on September 19, 2017 up by $3.2bn from March 2017 (Stats NZ, 2017).

New Zealand FDI as at Jun 2018 was $1.1bn but dropped by $353.6m compared with the previous quarter of 2017 (CEIC, 2018). According to Statistics New Zealand (2016), FDI in New Zealand was $100.6bn as at December 31, 2016, indicating an increase of $3.0bn when compared with 31 December 2015.

However, FDI in New Zealand increased by $684m in the third quarter of 2018. In the years 2000 to 2018 FDI in New Zealand averaged $469.77m reaching an all-time high of $309.6m in the first quarter of 2001 and record low of -7322 fourth quarter of 2001 (Trading Economics, 2018).

This was because of an increase in FDI from Australia, United Kingdom, Hong Kong and China. On the other hand, FDI from Canada and Singapore dropped. Similarly, New Zealand’s investment overseas was $24.9bn which indicated a drop of $1.4bn compared with the same time in 2015.

The genesis of recent increases in the flow of FDI can be traced to 2015 when the New Zealand government created three strategies to attract more FDI to stimulate more investment and growth in New Zealand (Holden, 2016). The priorities of the strategies were to attract high-quality foreign direct investment in New Zealand where it has a competitive edge; to attract overseas investment in research and development by encouraging multinational corporations to locate their R&D activity in New Zealand; and to expand New Zealand’s pool of smart capital by encouraging investors and entrepreneurs to invest in New Zealand.

The New Zealand government did this realising the importance of FDI as a source of capital for New Zealand firms facing the challenges of raising capital by domestic means. The Government also promoted FDI, believing that foreign investments in the domestic economy improve domestic firms’ productivity and innovation through transfer of technology and managerial knowledge and skills. FDI in New Zealand could also stimulate export to international markets, making it easier to realise foreign exchange earnings. This strategy as adopted has led to increases in FDI across the New Zealand economy and firms with FDI making important contributions to regional growth and development as well as job growth.

Foreign Investments in New Zealand and Sources

Sharan (2012) explains foreign investment as capital flows from one nation to another, most times reflecting foreign ownership and management stakes in local corporations and assets of a given business (Sharan, 2012). Foreign investments are always welcome in New Zealand because of their positive contribution to the New Zealand economy.

Understanding the sources of FDI in New Zealand will create awareness of countries having substantial investments in New Zealand and New Zealand links with the world. This study briefly analyses the foreign investment in New Zealand of three countries: Australia, United States and China.

Australia

Australia has significant investment in New Zealand. Stats NZ (2016) reported that out of $386.4bn of foreign investment in New Zealand, 58.3% was from Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. New Zealand stats also reported in 2016 that of the total sum of $227.4bn of New Zealand investment abroad, 62.9% was in Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. However, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (2017) reported that the Australian investment in New Zealand totals $103,040bn and $62,094bn of this is in FDI. On the contrary, NZ investment in Australia is $45,059bn and $5,820bn of this is in FDI. Australian direct investment into the New Zealand economy is more significant in the financial and insurance sectors than others. This could be because returns on investing in the banking and other financial sectors are significantly higher than from other sectors. Earl (2017) points out that there has been a great increase on the returns on investment in the banking sector from 2010 which peaked in 2012.

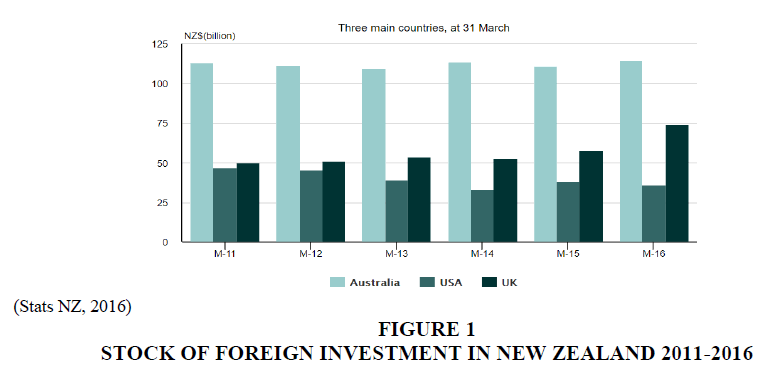

Figure 1 below indicates that as at 31 March 2016 Australia had over $100bn foreign investment in New Zealand; US had about $40bn investment, while the UK had about $75bn of foreign investment in New Zealand.

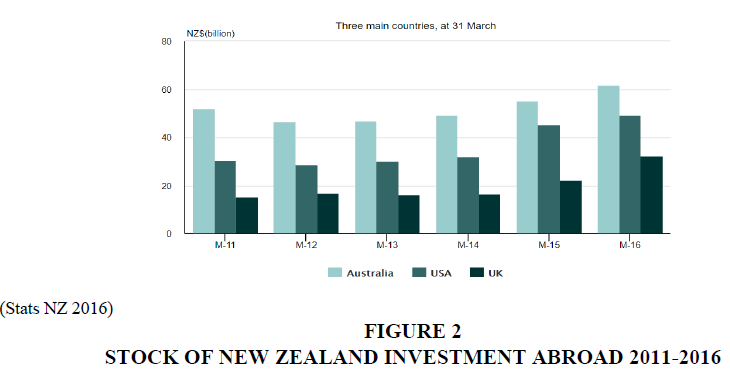

Accordingly, Figure 2 below represents the stock of New Zealand investment abroad. As at March 2016 New Zealand had investments of over $60 billion in Australia with over $50 in the US and over $30 billion is invested in the UK.

The US

The US has substantial investment in New Zealand. According to the Office of the United States Trade Representative (2015) the stock of U.S. FDI in New Zealand totalled $7.2bn in 2015 while New Zealand's FDI in the United States totalled $585m the same year. The US direct investment in New Zealand is in the areas of finance, transportation, energy, service industry and wholesale trade sectors. Over 300 US based businesses have subsidiaries in New Zealand, though they mostly operate through local agents and or joint ventures. According to Gray (2016), Canterbury, Otago and some cities in other areas of the South Island account for 49% of US investments in New Zealand. However, KPMG (2015) claimed that between 2013 and 2015 United States and Canada were New Zealand’s most significant sources of FDI.

China

In recent years, Chinese investment in New Zealand has increased, attaining $6.2bn in 2016 (New Zealand Statistics, 2016). China invested in Envirowaste and Waste Management, Synlait, PGG Wrightson and Fisher and Paykel Appliances. It also has substantial investments in the Fletcher Building’s Formica Group and Fonterra (Naidu-Ghelani, 2015). More than one third of China’s investments are in infrastructure and utility sectors. For example Beijing Capital Group acquired New Zealand’s largest waste management firm for $950m in 2014. China also increased its stake in the primary sector by investing $800m in the dairy industry of New Zealand (Kendall, 2014). China’s investment in New Zealand is motivated by the Free Trade Agreement between the two countries that started in 2008 (Omisakin, 2018) and the attraction of New Zealand as a positive destination for investment.

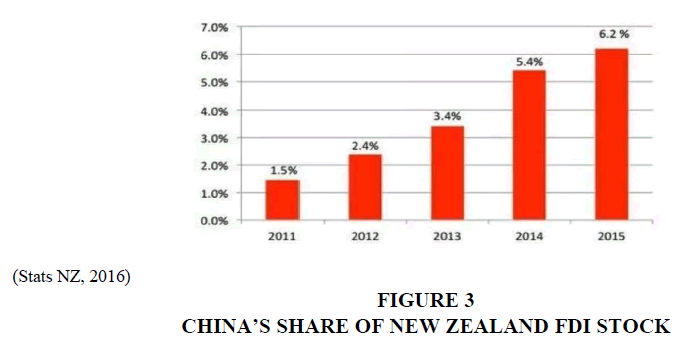

Figure 3 indicated that Chinese investment into New Zealand has increased astonishingly. China’s share of New Zealand FDI has grown from a low base of 1.5% in 2011 to 6.2% in 2015. This is a 160% increase since 2011.

Foreign Investments in Few New Zealand’s Economic Sector

The finance and insurance sectors are the most attractive sectors for foreign investments inflow. In 2016, about a third of foreign investment flows came to the finance and insurance business sectors followed by the manufacturing industry and agriculture, forestry and fishing industries (Stats NZ, 2016). Dairy, forestry and milk processing realized the highest flow in the agriculture business sector. Perhaps New Zealand realises easy flow of FDI because of her various trade agreements (Omisakin, 2018) and perhaps because of the belief that New Zealand is a prosperous country.

Investments in Dairy, Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing

Substantial foreign investment went into the dairy sector in 2015. Investors focused on buying dairy land in the South Island with Chinese investors being the major buyers of dairy lands. O'Meara (2016) argues that US investors lead in the act of land acquisition by accounting for 40% of total forestry land transactions in New Zealand in 2016. In the same forestry sector Europe had 13% land transactions followed by China with 12%. Between 2013 and 2016 China invested $1.3bn in the dairy and milk processing sector representing 28% of total investment from China in these years. The China based Yii Group had the largest single investment in dairy during this period by establishing a new milk processing plant in South Canterbury worth $214m. Another substantial investment within the same period was the sale of Goodman Fielder by an Australian based company to Wilmar International, Singapore worth $1.3bn. (Hutching, 2016). However, the scope of investments in New Zealand by Asian investors and North American investors indicates that Asian investors have a narrow focus, investing in dairy sector, business, food and waste management compared with American, Canadian and Australian investors who are more interested in investing in the agricultural sector of the economy, perhaps for longer term.

Role, Impact and Effects of Foreign Investments in New Zealand’s Economy

This section of the study briefly analyses the role, effects and impacts of FDI on some aspects of the New Zealand economic sector.

Skills, Jobs, and Wages

FDI has had positive effects on job numbers, wages and skills acquisition in the New Zealand labour market. Firms with FDI employ the largest number of employees in New Zealand. According to the New Zealand Government (2015), firms with FDI make up only 2% of the total number of firms, but they constitute 47% of firms employing over 100 employees. In the years 2014 and 2015, about one fifth of employees in New Zealand worked for FDI based firms (OECD, 2017). Therefore, firms with FDI help in employment expansion compared with New Zealand owned firms. The New Zealand Government (2015) argues that firms with FDI pay higher wages and raise wages more often than New Zealand owned firms. Linking New Zealand to more multinational firms globally have created open access to top levels of international talent, leading to skill transfer and improvement in overall skills in New Zealand, making New Zealand more attractive to further FDI and creating capabilities for New Zealand to increase its conduct of ODI.

Capital

According to Iyer et al. (2019) New Zealand has challenges meeting its domestic investment needs because these needs are usually greater that the national savings. The author concluded that the available alternative to New Zealand is FDI. Therefore, the most important direct effect of FDI on the New Zealand economy is the provision of capital which has helped increased diversity of risk sharing options available for firms and investors, leading to efficient capital markets matching the needs of businesses and investors. This enhances New Zealand’s ability to realise lower average cost of capital for its firms. FDI has also helped New Zealand firms unable to raise capital in the domestic economy to access foreign funding. FDI has become a stable source of funding for New Zealand firms and constitutes a medium of commitment by the investor.

Productivity and Innovation

FDI has had a direct impact on New Zealand’s productivity and innovation through investing in firms’ transfer of technology, knowledge know-how and skills. Often foreign firms in New Zealand contribute indirectly to improvement of productivity by interacting with other domestic based businesses. New Zealand’s engagement in overseas direct investment (ODI) also facilitates domestic productivity improvement by exposing local firms to new technology abroad as well as new management skills and techniques. Engagement in ODI can lead to development of new products and access to bigger and new markets.

Exporting Firms and Internationalisation

It is obvious in New Zealand that firms with FDI are among the most productive, and their focus is on export because it may be unrealistic for them to base their sales and expected profit in New Zealand. Therefore, most engage in export. By exporting, they become more connected to international markets, and the multiplier effect of this in the long run will be such firms becoming multinational firms. New Zealand’s trade agreements often help both FDI firms and domestic firms to become exporting firms and attain international status (Omisakin, 2018). Wilkinson & Acharya (2014) concluded that FDI constitutes a tool in building New Zealand as an export-based economy.

Impacts and Effects on Stakeholders

The author believes understanding of the economic and societal impacts of FDI on the New Zealand economy would involve evaluation its effects on various stakeholders of the economy. Therefore, this section of the study constitutes an in-depth analysis of the impact and effects of foreign investments on stakeholders (economy, households and business, government, social, environmental and political).

Households and Business

It is obvious that FDI has helped reduce interest rates and make funding to businesses and households affordable and easy to access. This is attainable because the New Zealand government adopted an open regime for investments, reducing the country’s risk on investment. The opposite of this would lead to high borrowing costs, especially in New Zealand where domestic saving is insufficient for investment needs. Prior to New Zealand’s adoption of aggressive policies of FDI, the cost of borrowing from financial institutions was high. This situation forced firms to pass the cost of borrowing onto their production costs, leading to higher unit prices for their products. Obviously, this leads to higher living costs.

Apart from massive gains brought by FDI to domestic firms through access to competition, innovation and advanced technologies, FDI helps to revive cities and sectors of the economy by buying over or injecting fresh funds into them. This creates opportunities for households with greater choice of consumable goods and services to improve their standard of living. A good example was given by Devlin (2015), citing the $20m refit in Wellington by retailer David Jones, an Australian based South African owned business. This investment subsidises the struggling Kirkcaldies and Stains store.

However, the utmost concern of the author is the negative impact of FDI in the property sector. Investments are more significant and more conspicuous in major cities, leading to unaffordability and forcing kiwis to move to other regions where they can afford to purchase properties.

Government

The government sees FDI as a golden opportunity to grow, develop and boost the economic status of the country. FDI has helped improve New Zealand’s export progress by offering enough equity to assist exporters grow their businesses, thereby linking domestic firms with international markets and distribution networks. FDI has also helped create linkages to international markets, providing a needed tool for exporters. FDI, therefore contributes to the entire economic framework of the country. Government was able to attain this by encouraging foreign investments through implementation of tax incentives to foreign investors (Wolters Kluwer, 2019). The government also simplified FDI related laws to facilitate foreign investors’ access to the local market. However, the major challenge of government is how to find a balance between domestic investors and foreign investors as sometimes foreign investment creates pressure on the government to implement rules and regulations resulting from excessive investments.

Economic Impact

Although FDI is necessary for the New Zealand economy, it presents a certain degree of risk of exposure. Despite this, FDI in all its forms has been positive for the New Zealand economy. It has been a vital means of raising capital for New Zealand firms that are not capable of raising investments in the domestic economy. Wilkinson & Acharya (2014) argue that without FDI it might be difficult for New Zealand to become an export led economy.

However, FDI does have some negative impacts on the domestic economy. It depends heavily on foreign investments which could leave the country vulnerable to global market and exchange rate volatility and other global economic shocks, leading foreign investors to repatriate their profits. FDI could lead to uncertainty in the domestic economy, especially when a foreign investor does not invest profit in the domestic economy but the home country.

Social Impact

FDI has an immensely positive impact on the entire society of New Zealand. For instance, FDI has created employment opportunities, enhanced choice of consumables and service, thereby creating selection opportunities and improving the economy. However, evolution of foreign ownership of New Zealand businesses constitutes transferring New Zealand business functions, ownership and management offshore, resulting in redundancy of domestic business managements, ownership and employees leading to a huge negative impact on society. Lall & Narula (2006) argue that excessive foreign investment in the housing sector could lead to negative housing affordability on the part of Kiwis. The authors recognise this as another adverse impact of foreign investments (Lall & Narula, 2006) where the demand in the housing market by foreign buyers leads to shortages of properties for New Zealanders to buy. Hence, New Zealanders are negatively affected.

Political Impact

Ulterior motives of some foreign investors could have a negative impact on the country’s national interest. This could be in the areas of national security or impact on market competition. The question is: does the New Zealand domestic regulatory framework provide limitations on foreign investment by ensuring that all companies function within boundaries that protect public welfare? If this is done, then it will ensure that policies do not discriminate between local and foreign investors (Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment, 2017).

Adverse Impact of Foreign Investments in New Zealand

FDI capital inflows are usually accompanied by long-term outflow that may not provide benefits to New Zealand. According to Czinkota (2015) multinational companies often use their home-based suppliers rather than using domestic supplier networks. The same scenario applies to New Zealand multinational companies. For an instance, multinational chains building hotels in New Zealand often use foreign currency to import supplies even when such could be procured in New Zealand.

Another negative impact is the ability of foreign invested firms to hire more efficient employees from domestic firms using higher salaries to attract them, thereby leaving lower quality staff in the domestic firms. This may lead to the natural death of domestic firms as they may be unable to compete with foreign firms (UK Essays, 2016). The only solution for domestic firms is to pay wages high enough to compete with those of foreign firms.

If FDI is not well managed, it could lead to a dual economy creating two sectors, one developed, mostly owned by foreign firms and investors and the other underdeveloped, mostly owned by domestic investors. This could lead to one sector of the New Zealand economy being heavily capitalised or capital intensive, while the other will be labour intensive.

However, I will advise the government to have a second thought on its operations of FDI because foreign invested firms are mostly concerned with repatriating their profits from investment no matter how they are treated. To avoid taxes on high volume transaction they use transfer prices. Government should realise that profit repatriation constitutes capital outflows from the New Zealand economy and negatively impacts the balance of payment (Patil, 2012).

Another critical factor associated with FDI is politics. Politicians are concerned with the voices of the minority about the possibility of FDI eroding their sovereignty which may lead to their becoming tenants in their own land. This led to the question: “What shall we call it if New Zealand merges with Australia?” (Horn, 2001). The answer shall be “Australia”. The rate at which New Zealanders sell their farmland and landed property to foreign investors is of great concern to all. The deteriorating level of the situation made John Key then New Zealand Prime Minister to say: "I'd hate to see New Zealanders as tenants in their own country and that is a risk, I think, if we sell out our entire productive base." (Key, 2010).

The potential impact of FDI, especially on people, is in real estate. Investors in New Zealand are keener on real estate because the demand is higher than supply, as essentially the real estate sector is driven by FDI. This potentially has negative social impacts on housing affordability for New Zealanders. Similarly, land in New Zealand today has become more expensive because chunks of land in New Zealand are bought by foreign investors.

Conclusion

It cannot be overemphasized that New Zealand needs FDI to be afloat. Obviously, this has to do with the population and cost of living, especially in areas of housing unaffordability. For instance, the Real Estate Institute of New Zealand [REINZ] (2018) found that it would take a couple in Auckland 16 years to save for a deposit needed to buy a house worth $670,000. It is argued that there are some perceived adverse consequences of FDI such as fear of losing sovereignty, creating a dual economy if FDI is not well managed, and ulterior motives of some investors manipulating the opportunities in FDI for themselves at the expense of the entire economy.

Despite these drawbacks, FDI has provided immense benefits to the New Zealand economy. For instance, FDI has assisted New Zealand to meet needed domestic investment requirements in the face of its inability to mobilise domestic savings. Foreign investments have created job opportunities in the country, enabled higher wages and created a competitive environment for domestic firms. It has also facilitated lower interest rates, expanded the choice and availability of goods and services.

Recommendations

The New Zealand government should take some measures to enhance the survival rate of local firms. As any country that failed to protect it production industry will meet its waterloo in future because when the MNC, the direct and indirect investors are through with such country they will always leave. Continuous investment in any country is a function of many factor and these factors are not static. After all, FDI and MNC operate mostly on theory of free entry and free exit.

Housing affordability is one of the major needs of all New Zealand otherwise the bulk of New Zealanders will become tenants in New Zealand in the next 10 to 20 years. Purchasing a house has become very difficult for the majority of New Zealanders because of high cost and in my opinion low wages. In this regard housing affordability and an increase in housing supply through a proper resource management program to allocate properties to local citizens should remain high priorities for the government. I think kudos should be given to the current government of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern by intensifying increases in the number of affordable houses for people to buy.

New Zealand may need to revamp FDI regulations to include some stricter rules in screening foreign investors to avoid security and money laundering issues.

New Zealand should realise that over dependence on foreign investments can expose the country to exchange rate crises and balance of payment deficits as a result of excessive importation of needed materials from investors’ home countries, especially when such materials are available in New Zealand.

References

- Aitken, B., Hanson, G.H., & Harrison, A.E. (1997). Spillovers, foreign investment, and export behavior. Journal of International economics, 43(1-2), 103-132.

- Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (2017). Trade & investment data, information & publications. Available from: https://dfat.gov.au/trade/resources/Pages/trade-and-economic-fact-sheets-for-countries-and-regions.aspx

- Barnat, R. (2014). Strategic Management: Formulation and Implementation. Available from: http://applications-of-strategic-management.24xls.com/en135

- Buckley, P.J., & Casson, M.C. (1976). The Future of the Multinational Enterprise. London: Homes & Meier.

- CEIC. (2018). New Zealand Foreign Direct Investment. Available from: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/new-zealand/foreign-direct-investment

- Cushman, D.O. (1985). Real exchange rate risk, expectations and the level of direct investment. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 67(2), 297-308.

- Czinkota, M. (2015). Pros and Cons of Foreign Direct Investment. Thoughts on International Business, Marketing and Strategy. Available from: http://michaelczinkota.com/2015/03/pros-cons-foreign-direct-investment/

- Devlin, C. (2015). Spending on luxury attracted David Jones to Wellington. Available from: https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/74324376/null

- Disdier, A.C., & Mayer, T. (2004). How different is Eastern Europe? Structure and determinants of location choices by French firms in the Eastern and Western Europe. Journal of comparative Economics, 32, 280-296.

- Dunning, J.H. (1980) Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some empirical tests. Journal of International Business Studies, 11(1), 9-31.

- Earl, G. (2017). Australia’s changing investment orientation. Available from: https://bluenotes.anz.com/posts/2017/05/australia-s-changing-investment-orientation

- Gray, J. (2016). North America biggest investors in NZ - KMPG. Available from: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/the-country/news/article.cfm?c_id=16&objectid=11740021

- Holden, M. (2016). Economic impacts of foreign direct investment. Treasury Staff Insights:Rangitaki. Available from: https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/staff-insight/economic-impacts-foreign-direct-investment.

- Horn M. (2001). Economic questions: choice: for New Zealand, in Brown (ed) New Zealand and Australia - where are we going? New Zealand Institute of International Affairs at Victoria University, Wellington.

- Hutching, G. (2016). Harvard University expands dairy interests in South Island. Available from: https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/farming/85931665/harvard-expands-dairy-interests-in-south-island

- Hymer, S. (1976). The international operations of national firms: A study of foreign direct investment. Journal of International Management.

- Iyer, K., Stevens, P., & Tang, K. (2019). Productivity spillovers from foreign direct investment in new zealand. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255597175_Productivity_Spillovers_from_Foreign_Direct_Investment_in_New_Zealand_Manufacturing

- Iyer, K., Stevens, P., & Tang, K.K. (2011). Foreign and domestic ownership: Evidence of productivity spillovers from new zealand firm level longitudinal data. Ministry of Economic Development, New Zealand School of Economics, The University of Queensland, Australia.

- Kendall, R. (2014). Economic linkages between New Zealand and China. Reserve Bank of New Zealand Analytical Notes.Available from: https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/-/media/ReserveBank/Files/Publications/Analytical%20notes/2014/an2014-06.pdf

- Key, J. (2010). New Zealand sleeps while land sells. Available from: http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/blogs/3913679/New-Zealand-sleeps-while-land-sells

- Kokko, A., Tansini, R., & Zejan, M.C. (1996). Local technology capability and productivity spillovers from FDI in the Uruguayan manufacturing sector. Journal of Development Studies, 32(4), 602-612.

- KPMG. (2015). Foreign Direct Investment in New Zealand. KPMG New Zealand. Available from: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/08/KPMG-Foreign-Direct-Investment-analysis-August-2015.pdf

- Lall, S., & Narula, R. (2006). Understanding FDI-Assisted Economic Development. London:Routledge.

- Moosa, I.A. (2002). The determinants of foreign direct investment in MENA Countries: An extreme bounds analysis. Research report 0421. Department of Economics and Finance, La Trobe University, Victoria 3086, Australia. Available from: https://erf.org.eg/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/PRR0421.pdf

- Moran, T. (2016). Foreign direct investment. Wiley online library. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog216.pub2

- Naidu-Ghelani, R. (2015). China's New Zealand farm-buying runs into opposition. BBC News. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-34513287

- New Zealand Institute of Economic Research. (2016). Foreign direct investment in New Zealand. Available from: https://www.businessnz.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/114236/Foreign-Direct-Investment-in-NZ.pdf

- New Zealand, Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment. (2017). New Zealand Now. Available from: http://www.newzealandnow.govt.nz

- New Zealand Government. (2015). International investment for growth. Available from: https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2015-10/iig-bga-oct15.pdf

- Stats NZ. (2017). Foreign investment in New Zealand up to $404 billion. Available from: https://www.stats.go.t.nz/news/foreign-investment-in-new-zealand-up-to-404-billion

- Stats NZ. (2016). Investment by country. Available from: http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/economic_indicators/balance_of_payments/investment-by-country.aspx

- The Treasury. (2015). International Investment for Growth Report. Available from: https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/information-release/international-investment-growth-report

- OECD. (2017). New Zealand: Boost productivity and adapt to the changing labour market. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/newzealand/new-zealand-boost-productivity-and-adapt-to-the-changing-labour-market.htm

- O'Meara, P. (2016). Foreigners continue to invest heavily in NZ farms. RNZ News. Available from: https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/business/317103/foreigners-continue-to-invest-heavily-in-nz-farms

- Omisakin, O.M. (2018). New Zealand trade agreements and their economic and societal impacts: A Review. International Business and Management, 16(2), 38-48.

- Patil, S.B. (2012). Profit repatriation: The Foreign Direct Investment Incentive. Available from: https://wealthhow.com/profit-repatriation-foreign-direct-investment-incentive

- Realestate. (2017). NZ property report March. Available from: http://www.realestate.co.nz/blog/news/new-zealand-property-report-march-2017

- Scott-Kennel, J. (2004). Foreign direct investment to New Zealand. University of Auckland Business Review. https://www.uabr.auckland.ac.nz/files/articles/Volume6/v6i2-foreign-direct-investment-to-new-zealand.pdf

- Scott-Kennel, J. (2007). Foreign direct investment and local linkages: An empirical investigation. Management International Review, 47(1), 1-27.

- Sharan, V. (2012). International financial management (6th ed). India: PHI Learning.

- Trading Economics. (2018). New Zealand Foreign Direct Investment. Available from: https://tradingeconomics.com/new-zealand/foreign-direct-investment

- UK Essays. (2016). Negative effects of FDI in host countries economics essay. Available from: https://www.ukessays.com/essays/economics/negative-effects-of-fdi-in-host-countries-economics-essay.php?vref=1

- Vernon, R. (1966). International investment and international trade in the product cycle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80(2), 190-207.

- Wilkinson, B., & Acharya, K. (2014). Open for business: Removing the barriers to foreign investment. Reports & Media. The New Zealand Initiative.

- Wolters, K. (2019). Inward investment incentive program. New Zealand: Related Information. Avaiable from: http://www.lowtax.net/information/new-zealand/new-zealand-inward-investment-incentive program.html