Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 4

Networks of Migratory Flows of Talents in Interaction with Native Communities in the Literature from 2000 to 2023

José Marcos Bustos Aguayo, National Autonomous University of Mexico

Cruz García Lirios, Autonomous University of Mexico City

Francisco Rubén Sandoval Vázquez, Autonomous University of the State of Morelos

Javier Carreón Guillen, National Autonomous University of Mexico

Margarita Juárez Najera, Metropolitan Autonomous University

Citation Information: Aguayo, J.M.B., Lirios, C.G., Vázquez, F.R.S., Guillen, J.C., & Najera, M.J. (2023). Networks of migratory flows of talents in interaction with native communities in the literature from 2000 to 2023. Journal of Organizational Culture Communications and Conflict, 27(4), 1-9.

Abstract

The relationship between migratory flows and native communities has been a central issue on the research agenda. In this sense, the objective of the study was to establish the neural network of learning relationships between groups in order to anticipate conflict scenarios. An exploratory, cross-sectional and correlational study was carried out with a sample of 100 students in social service and professional practice in health services. The results show a learning network that goes from the risks to the criminalization of migrant flows with respect to the native communities. In relation to the state of the art, lines of research related to violence as an inhibitor of the formation of migrant talents are proposed.

Keywords

Native Communities, Criminalization of Migrants, Migration Flows, Risks, Neoclassical Theory.

Introduction

The history of migration from Mexico to the United States is long and complex, spanning different periods and motivations over time (Njock & Westlund, 2010). The key aspects of this story are:

19th and early 20th century: Migration flows from Mexico to the United States began in the 19th century with the annexation of Texas and the US-Mexican War (1846-1848). After the war, many Mexicans found themselves living in United States territory. In addition, the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) caused a wave of migration due to political and economic instability in Mexico.

1920s and 1930s: During the 1920s, there was an increase in demand for farm and railroad workers in the United States, which attracted many Mexicans. In 1924, the "Mexican Workers Program" was established, which allowed temporary workers to travel to the United States for agricultural work and return to Mexico after the season. However, this program did not fully resolve irregular migration.

1940s and 1950s: During World War II, the demand for labor increased further, leading to the signing of the "Bracero Program" in 1942. This program allowed Mexican workers to temporarily enter the United States to work in agriculture and other sectors. Although the program was supposed to be temporary, it was extended until 1964. Many braceros stayed in the United States after their contracts expired, contributing to permanent migration.

1960s: As the Bracero Program was reduced and finally ended in 1964, irregular migration began to increase. Economic and social factors in Mexico, as well as the search for better opportunities in the United States, continued to drive migration.

1980s: The economic crisis in Mexico during this decade, combined with the temporary relaxation of immigration policies in the United States, contributed to a significant increase in migration. Many Mexicans sought employment and economic stability by crossing the border.

1990s and 2000s: During these decades, migration continued, with an increasing focus on family reunification (Portes & Grosfoguel, 1994). Many Mexicans settled in the United States permanently, and Mexican communities grew in several cities.

21st century: Migration from Mexico to the United States continues to be a relevant issue today (Lichter & Johnson, 2009). Stricter immigration policies in the United States have led to increased border security and deportations, while in Mexico, efforts to improve the economy and living conditions have had an impact in reducing emigration at times.

Migration from Mexico to the United States has been accompanied by a series of challenges and problems over the years. Some of the most prominent issues include:

Irregular Migration and Risks for Migrants: Many Mexicans have chosen to cross the border irregularly due to strict immigration policies and the difficulty in obtaining visas. This exposes migrants to significant risks, including dangerous journeys through the desert, abuse by human smugglers, and the possibility of being arrested and deported.

Human Rights and Abuses: Migrants, especially those who cross the border irregularly, often face abuses from human smugglers, border agents, and other actors. This may include labor exploitation, physical violence, sexual assault, and detention in inhumane conditions.

Impact on Families: Many Mexican migrants leave their families behind in Mexico, which can have an emotional and economic impact on both sides of the border (Abbas, 2016). Families can be separated for long periods of time, which can lead to stress and emotional difficulties.

Discrimination and Racism: Mexicans and other groups of Latino origin have faced discrimination and racism in the United States (Nica, 2015). This can affect your job opportunities, education, and integration into American society.

Labor Exploitation: Many Mexican migrants work in the agricultural and construction sectors in the United States in precarious conditions and with low wages (Hooghe & De Vroome, 2017). The lack of labor protections and fear of being reported to immigration authorities often leaves workers vulnerable to exploitation by employers.

Pressure on Public Services: Mexican migration has also raised concerns about additional pressure on public services in some areas of the United States. This includes schools, health services and housing.

Legal and Administrative Challenges: The process of obtaining legal visas and work permits in the United States can be complicated and expensive. This may lead some migrants to opt for irregular migration or to stay in the country after the expiration of their visas.

Criminalization of Migration: At times, irregular migration has been criminalized in the United States, leading to the detention and deportation of migrants regardless of their individual circumstances (Davis & Lopez-Carr, 2010).

Impact on Mexico: The migration of young and working people from Mexico has often been associated with the "brain drain" and loss of talent in the country. This may affect the economic and social development of Mexico.

It is important to address these problems from a multidimensional perspective, considering economic, political and social factors in both countries (Reichman, 2013). Effective solutions could involve immigration policy reforms, the creation of economic opportunities in Mexico, the protection of migrants' rights, and the promotion of bilateral cooperation between Mexico and the United States.

There are various theories that seek to explain the reasons and dynamics behind migratory movements (Escobar & Beall, 1982). These theories encompass economic, social, political, and cultural factors that influence people's decision to leave their place of origin and move to another country.

Neoclassical or Profit Maximization Theory: This theory is based on the idea that people migrate to maximize their profits and improve their economic conditions. Individuals make rational decisions by weighing the potential benefits of migrating against the associated costs, such as risk, effort, and cost of migration.

Social Network Theory: This theory highlights the importance of social networks and family and community ties in the migration process (Escobar & Beall, 1982). People are often more inclined to migrate to places where they have friends or family who can offer support in terms of information, employment, and cultural adjustment.

Labor Market Segmentation Theory: This theory suggests that labor markets in host countries are divided into segments, with migrant workers filling jobs that local workers do not want to do due to poor working conditions or wages. Migrants fill gaps in certain labor sectors (Castelli & Sulis, 2017).

Migration Chains Theory: This theory is based on the idea that migration begins with an individual who emigrates and then establishes links and networks in the receiving country. These links facilitate the migration of other individuals from the same community, creating a migration chain.

Human Capital Theory: According to this theory, migration is driven by the search for greater investment in human capital, such as education and job skills, which can generate better economic opportunities in the receiving country.

Development and Underdevelopment Theory: This theory suggests that migration is a result of the economic and social imbalance between developed and underdeveloped countries. The lack of economic opportunities and poverty in the countries of origin can push people to migrate to places with better prospects.

Conflict Theory and Political Push: In some cases, political conflicts, persecutions, and human rights violations in the country of origin can drive people to seek refuge elsewhere. Political migration may be motivated by the search for security and freedom.

Social and Cultural Change Theory: Some people migrate in search of a change in their lifestyle, cultural values, and opportunities for a more fulfilling life. Migration can allow them to escape social or cultural restrictions in their place of origin.

These theories offer different perspectives on the reasons and dynamics of migration. However, it is important to keep in mind that migration is a complex phenomenon that can be influenced by multiple interrelated factors.

Migration has been the subject of numerous studies in various disciplines, including sociology, economics, anthropology, geography, demography and more. These studies have addressed a wide range of issues related to migration, such as motivating factors, migration patterns, economic and social impacts, migration policies, and much more.

Economics of Migration: Economists have investigated how economic factors, such as the difference in wages and employment opportunities between countries, influence decisions to migrate (Barcham et al., 2009). They also analyze how migration affects labor markets in both the country of origin and the destination country.

International Migration and Development: It studies how migration can influence economic and social development in both countries of origin and destination. The researchers examine how remittance flows (money sent by migrants to their families in the country of origin) affect the economy and quality of life.

Migration Policies: Studies on migration policies analyze how laws and regulations in destination countries affect migration flows and the experience of migrants. They also explore the effects of policies such as the regularization of undocumented immigrants and the protection of refugees.

Family Dynamics and Migration: Research in this field explores how migration affects families, including family dynamics when some members migrate while others stay in the country of origin. It examines how family separations and migration can affect relationships and family cohesion.

Migration and Culture: Anthropological and sociological studies have investigated how migration can influence cultural identity and the way in which migrants interact with host societies (Mung, 2008).

Female Migration: Specific research has been done on the migration of women and how their experiences may differ from those of men. This includes analysis of job opportunities, support networks, and specific challenges faced by migrant women.

Migration and Health: Studies examine how migration can affect the health of migrants and their families, considering factors such as access to health care, working conditions, and psychological stress associated with migration.

Internal Migration: In addition to international migration, the patterns and motivations of internal migration within a country have also been studied.

Forced Migration and Refugees: Forced migration due to armed conflicts, persecutions and natural disasters is analyzed in depth. Studies in this area focus on the challenges faced by refugees and internally displaced persons, as well as humanitarian responses (Delugan, 2010).

Social Networks and Transnational Communities: It investigates how social networks and transnational communities influence migration, cultural adaptation and integration of migrants in destination countries. Migration is a broad and multidisciplinary topic that continues to be the subject of constant research due to its impact on society, the economy and politics around the world.

Measuring migration involves collecting data and statistics on the movements of people from one place to another, either within a country (internal migration) or between different countries (international migration). These data are essential to understand and analyze migration patterns, as well as to formulate policies and make informed decisions.

Censuses and Surveys: National censuses and household surveys usually include questions about people's place of birth and previous residence. These data provide an overview of migration in a country and help identify demographic patterns.

Immigration and Emigration Records: Governments keep records of the entry and exit of people at borders (Sadiq, 2009). These records provide information on international migration, including details on nationality, purpose of travel, and length of stay.

Visa and Residence Permit Statistics: Data on visas issued and residence permits granted to foreigners can be useful in understanding who has legal permission to reside in a country (King, 2001).

Remittance Records: The measurement of remittances, that is, the funds sent by migrants to their countries of origin, provides information on the magnitude of international migration and its impact on the economy.

Migrant Surveys: Specific surveys of migrants can be carried out to obtain detailed information on their motivations, experiences and working conditions. This is particularly relevant to understanding the social and economic dynamics behind migration.

Longitudinal Studies: Longitudinal studies follow individuals and households over time, making it possible to analyze changes in residence and migratory behavior throughout their lives.

Social Network Data Analysis: In the digital age, social network data analysis can provide insight into migration flows through online connections and relationships.

Cross-Data: Combining data from different sources, such as censuses, border records, and employment records, can often provide a more complete picture of migration (Rosenblum & Brick, 2011).

Statistical Models: Statistical and mathematical models can be used to estimate the magnitude and trends of migration, especially when data is incomplete or limited.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS): GIS can be used to map migration patterns and visualize migration-related geospatial data (Gardner, 2010).

The accuracy and quality of migration data are critical for a complete and accurate understanding of this phenomenon. However, measuring migration can be challenging due to irregular migration, under-documentation, and under-reporting.

However, the repositories of indexed journals, as well as the results published in the journals, are another unexplored data source that would allow confirming the trends, relationships, or relative gradients of migratory flows with respect to the native communities.

The Purpose of the Study

Given that the studies that measure the differences between the migratory flows with respect to the native communities have not been addressed since the review of the literature, the objective of the present work was to establish the axes and topics of the research agenda in the matter, as well as the significant differences between the indicators of migratory flows with respect to migrant communities, considering the evaluation of students assigned to self-help and self-help centers for migrant flows from central Mexico.

Are there significant bibliometric differences between migratory flows with respect to native communities considering the evaluation of students involved in professional practices and social service in migrant and native communities?

Hypothesis 1. The literature related to migratory flows and native communities is centered on a neoclassical paradigm in which significant differences prevail from an economic order. Therefore, significant differences between the study groups are expected if economic aspects are observed.

Hypothesis 2. Given that the state of the art suggests that migratory flows are different from migrant communities in the economic sphere, the literature related to these phenomena would indicate a preponderant network of relationships in education, training, training, wages, income, remittances and entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 3. Derived from the differences between migratory flows and the native communities from a neoclassical approach, these will persist in the other emerging paradigms, since the risk, loss or gain approach will prevail over the network approach.

Method

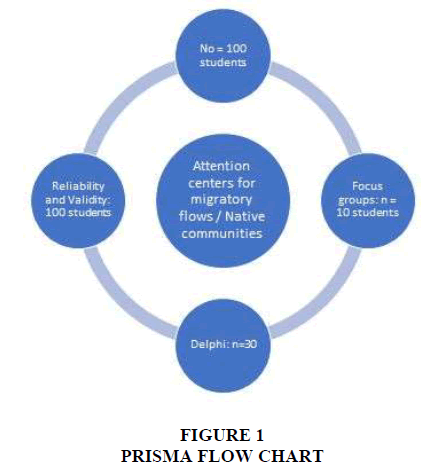

Design: A cross-sectional, correlational and exploratory study was carried out Figure 1.

Sample: A sample of 100 students was selected (M=23.2 DE=4.3 years and M=9'878.00 DE=3'423.00 monthly income) considering their participation in social service and professional practices in health centers for migrants and natives of central Mexico.

Procedure: The homogenization of the concepts was established through focus groups of 10 students. Next, the evaluation of the findings was established with a Delphi study of 30 students. The reliability and validity of the instrument was established with 100 students assigned to health centers for migrant flows and native communities. The search for the findings was carried out in institutional repositories: Redalyc and Scielo based on keywords: "migratory flows" and "native communities" in the period from 2000 to 2023. The concepts were discussed in focus groups of 10 students and evaluated. the contents in a Delphi study with 30 students who assigned a 0=“not at all agree” to a 5=“somewhat agree” to each of the findings with respect to their assignment to a category of analysis. The reliability and validity of the instrument was established with a sample of 100 professional practitioners and social servants.

Analysis: Data were captured in Excel and processed in JASP version 16. Centrality, clustering, and structuring parameters were estimated. Values close to unity were interpreted as evidence of neural network learning and values close to zero as evidence of informative bias.

Ethics: The study was approved by the ethics committee of the International Research Center with registration number CEDINTER-LAZE-2023-0001.

Results

Centrality is a property of learning networks that consists of intermediation, proximity, gradation and influence of the nodes with respect to themselves. In this sense, the central node is related to criminalization. In other words, the problems of migratory flows and migrant communities lie in the risks and losses posed by the invasion of migrants in native communities Table 1.

| Table 1 Centrality Measures Per Variable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| networks | ||||

| Variable | Betweenness | Closeness | Strength | Influence |

| Risk | -0.744 | 0.017 | -0.175 | -0.278 |

| Irregularities | 1,843 | 1,309 | 0.807 | 0.292 |

| Abuse | -0.744 | -1,653 | -1,417 | -0.594 |

| Rights | -0.744 | -0.744 | -0.942 | -1,923 |

| Remittances | -0.420 | -0.818 | -0.703 | -0.635 |

| Discrimination | -0.420 | 0.101 | -0.348 | 0.229 |

| Racism | -0.744 | -0.229 | -0.118 | -0.049 |

| Exploitation | -0.420 | -0.456 | -0.002 | 1,391 |

| Challenges | 1,196 | 1,208 | 0.905 | 1,548 |

| Criminalize | 1,196 | 1,266 | 1,994 | 0.018 |

The grouping suggests the attraction of a preponderant node with respect to the other nodes. That is, according to the four grouping parameters, the hegemonic node is the one related to the rights of migrant flows and native communities Table 2.

| Table 2 Clustering Measures Per Variable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| networks | ||||

| Variable | Barratt | Onnela | WS | Zhang |

| Abuse | 0.916 | -1,314 | 0.548 | -0.615 |

| Challenges | -0.875 | 1,454 | -1,280 | -0.535 |

| Criminalize | -0.927 | 1,169 | -1,077 | -0.552 |

| Discrimination | -0.995 | -0.488 | 0.548 | -0.639 |

| Exploitation | -1,485 | -0.402 | -1,077 | -0.937 |

| Irregularities | 1,340 | 0.798 | 0.548 | -0.631 |

| Racism | 0.583 | 0.990 | 1,158 | 1,435 |

| Remittances | 1,063 | -0.444 | 1,158 | -0.391 |

| Rights | 0.172 | -0.982 | 0.548 | 1,316 |

| Risk | 0.209 | -0.783 | -1,077 | 1,550 |

The structure of the learning network indicates the relationships between the nodes. In the case of the structure that makes up the risk nodes with criminalization (0.619) and irregularities (0.586), rights with challenges (0.435), remittances with exploitation (0.715), discrimination with challenges (0.625), racism with criminalization (0.602) and challenges with criminalization (0.726) constitute the correlation structure that suggests learning from the risks of criminalization Table 3.

| Table 3 Weights Matrix |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Networks | |||||||||||

| Variable | Risk | Irregularities | Abuse | Rights | Remittances | Discrimination | Racism | Exploitation | Challenges | Criminalize | |

| Risk | 0,000 | 0.586 | -0.140 | 0.070 | -0.024 | 0.021 | -0.373 | -0.104 | -0.231 | 0.619 | |

| Irregularities | 0.586 | 0,000 | -0.234 | -0.022 | -0.300 | 0.369 | 0.378 | 0.437 | 0,000 | -0.520 | |

| Abuse | -0.140 | -0.234 | 0,000 | 0.138 | -0.105 | 0.297 | 0.136 | 0.224 | 0,000 | -0.040 | |

| Rights | 0.070 | -0.022 | 0.138 | 0,000 | -0.115 | -0.240 | 0,000 | -0.095 | 0.435 | -0.526 | |

| Remittances | -0.024 | -0.300 | -0.105 | -0.115 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0.715 | 0.315 | -0.231 | |

| Discrimination | 0.021 | 0.369 | 0.297 | -0.240 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0.045 | -0.222 | 0.625 | -0.232 | |

| Racism | -0.373 | 0.378 | 0.136 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0.045 | 0,000 | 0.210 | -0.465 | 0.602 | |

| Exploitation | -0.104 | 0.437 | 0.224 | -0.095 | 0.715 | -0.222 | 0.210 | 0,000 | -0.115 | 0.166 | |

| Challenges | -0.231 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0.435 | 0.315 | 0.625 | -0.465 | -0.115 | 0,000 | 0.726 | |

| Criminalize | 0.619 | -0.520 | -0.040 | -0.526 | -0.231 | -0.232 | 0.602 | 0.166 | 0.726 | 0,000 | |

Discussion

The contribution of this work to the state of the art lies in the establishment of a learning neural network that goes from risks to criminalization. It means then that the neoclassical approach is preponderant in the literature consulted and the evaluations of professional practitioners and social servants. Such a neoclassical approach suggests that risks are indicators of losses in the socioeconomic structure of a region (Núñez, 2009). Thus, studies related to migratory flows and migrant communities suggest that these risks determine the differences between groups. One consequence of this approach is the emphasis on criminalization as the central axis of the investigative agenda. In this sense, the studies on the formation of human capital and the networks of talent flows indicate that it is these risks that inhibit the development of migrant flows, even when the level of education is high. That is to say, the native communities are far from benefiting from the reception of talents, since it is the socioeconomic risks that cut short their academic, professional and labor training. Lines of study alluding to anti-immigrant policies would indicate the risks that inhibit the academic, professional or labor development of migrants with respect to the native communities, as well as the talent reception policies that hinder professional and labor training, even when academic training is postgraduate.

However, the limits of the study correspond to the size of the sample, since the analysis of relationships between the nodes would allow a better explanation of the determinants of remittances. Therefore, an amplification of the study in terms of the sample and the observable nodes will allow the contrasting of an econometric model to anticipate remittances as indicative of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

Conclusion

The objective of the study was to establish a structural learning network of the relationships between migratory flows and native communities in a review from 2000 to 2023 and evaluated by students in social service and professional practices from central Mexico. The results indicate that a network is woven which goes from the risks to the criminalization of migrant flows. The literature consulted, reviewed and evaluated indicates a bibliometric prevalence of migratory flows as risks for native communities due to their degree of criminalization in the media. In relation to the state of the neoclassical art, the results suggest the extension of the study towards the exploitation and criminalization of migrants.

References

Abbas, R. (2016). Internal migration and citizenship in India. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42 (1), 150-168.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barcham , M., Scheyvens , R., & Overton, J. (2009). New Polynesian triangle: Rethinking Polynesian migration and development in the Pacific. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 50 (3), 322-337.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Castelli, F., & Sulis, G. (2017). Migration and infectious diseases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 23 (5), 283-289.

Davis, J., & Lopez- Carr, D. (2010). The effects of migrant remittances on population–environment dynamics in migrant origin areas: international migration, fertility, and consumption in highland Guatemala. Population and Environment, 32, 216-237.

Escobar, G., & Beall, C.M., (1982). Contemporary patterns of migration in the Central Andes. Mountain Research and Development, 63-80.

Gardner, A.M., (2010). City of strangers: Gulf migration and the Indian community in Bahrain. Cornell University Press.

Hooghe, M., & De Vroome, T. (2017). The perception of ethnic diversity and anti-immigrant sentiments: A multilevel analysis of local communities in Belgium. In Cities, Diversity and Ethnicity. 49-67.

King, R. (2001). The troubled passage: migration and cultural encounters in southern Europe. Liverpool Studies in European Regional Cultures, 9, 1-21.

Lichter , D.T., & Johnson, K.M. (2009). Immigrant Gateways and Hispanic Migration to New Destinations 1. International Migration Review, 43 (3), 496-518.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mung, E.M. (2008). Chinese migration and China's foreign policy in Africa. Journal of Chinese Overseas, 4 (1), 91-109.

Nica, E. (2015). Labor market determinants of migration flows in Europe. Sustainability, 7 (1), 634-647.

Njock , JC, & Westlund , L. (2010). Migration, resource management and global change: Experiences from fishing communities in West and Central Africa. Marine Policy, 34 (4), 752-760.

Portes, A., & Grosfoguel, R. (1994). Caribbean diasporas: Migration and ethnic communities. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 533 (1), 48-69.

Reichman, D. (2013). Honduras: The profiles of remittance dependency and clandestine migration. The Online Journal of the Migration Policy Institute.

Rosenblum, MR, & Brick, K. (2011). US immigration policy and Mexican/Central American migration flows. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Sadiq, K. (2009). When Being "Native" Is Not Enough: Citizens as Foreigners in Malaysia. Asian Perspective, 5-32.

Received: 04-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. JOCCC-23-13921; Editor assigned: 06-Jul-2023, Pre QC No. JOCCC-23-13921(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Jul-2023, QC No. JOCCC-23-13921; Revised: 27-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. JOCCC-23-13921(R); Published: 31-Jul-2023