Research Article: 2018 Vol: 21 Issue: 4

Motivation to Adopt Game-Based Learning (GBL) for Employee Training and Development: A Case Study

Satoshi Sugahara, Kansei Gakuin Daigaku-Nishinomiya Uegahara Campus

Abstract

The objective of the present study is to investigate the motivation for applying a Game Based Learning (GBL) to business education and training for business persons and practitioners working at Small And Medium-Sized Entities (SMEs). To explore this topic, we conducted an exploratory study focusing on a highly successful GBL initiative called the Management Game (MG). The MG is a board game type of GBL that helps participants learn management and accounting skills by playing. The MG is organized as a weekend workshop for training purposes for participants who are usually managers or employees of SMEs.

For the data collection, an open-ended type questionnaire was administered to collect qualitative data regarding the participants' perceptions of the MG as a business training tool and its learning efficacy. Data for this research were collected from business persons who participated in an MG workshop on February 25 to 26, 2017. A total of 69 people attended the two-day workshop for training in business and accounting skills and competencies. Of the 69 participants, 58 agreed to respond to our non-anonymous questionnaire.

The results of our study showed that the most common motivation for using MG as an educational tool for business practitioners is to teach the idea of participative management to employees. We also found that the aim of teaching participative management skills is to foster employees' decision-making skills from a managerial perspective. In addition, accounting literacy is regarded as an antecedent to developing effective decision-making skills.

Keywords

Game-Based Learning, Employee Training, Business Education, Accounting Education.

Introduction

There has been a recent surge in educational research on how games influence learning (Vlachopoulos & Makri, 2017; Carenys & Moya, 2016; Qian & Clark, 2016). Game-Based Learning (GBL) uses games as a technique to promote learning, skill acquisition, and training (Randel et al., 1992; Boyle et al., 2011). The objective of the present study is to investigate the motivation for applying GBL to business education and training.

GBL is often used for corporate training and formal education because playing games creates positive experiences and promotes effective learning. Prior studies have shown that GBL is consistent with modern theories on effective learning, which propose that learning activities should be active, situated, problem-based, interactive, and socially mediated (Boyle et al., 2011). Prior research has found empirical evidence that GBL has cognitive (e.g., perceptual skills), behavioral (e.g., social skills, teamwork), and affective (e.g., motivation, engagement, satisfaction) learning outcomes (Carenys & Moya, 2016; Vlachopoulos & Makri, 2017).

It is well established in the existing business education literature that GBL strategies generate more effective learning outcomes than non-GBL approaches (Gamlath, 2007; Laing et al., 2009; LeFlore et al., 2012; Marriott et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2016; Eckhaus et al., 2017; Koivisto et al., 2017). However, most prior studies have examined GBL’s effect on classroom learning; thus, there is a gap in the research concerning business persons and practitioners.

Given this background, our study examines the characteristics of GBL as a successful learning tool for business persons and company employees. To explore this topic, we conducted an exploratory study focusing on a highly successful GBL initiative called the Management Game (MG). The MG is a board game type of GBL that helps participants learn management and accounting skills by playing. The MG is organized as a weekend workshop for training purposes for participants who are usually managers or employees of Small And Medium-Sized Entities (SMEs).

The results of our study showed that the most common motivation for using MG as an educational tool for business practitioners is to teach the idea of participative management to employees. We also found that the aim of teaching participative management skills is to foster employees’ decision-making skills from a managerial perspective. In addition, accounting literacy is regarded as an antecedent to developing effective decision-making skills.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the MG, while Section 3 reviews the related literature. The research design is discussed in Section 4. The results of the analysis are described in Section 5. Section 6 interprets and discusses the results. Finally, section 7 presents the conclusions of the paper.

The MG

The MG was invented by Jyunichiro Nishi, who was also the founder and coordinator of the business training workshop using the game. His initial motivation for creating the MG was based on his ambition to provide better opportunities for employees to learn the fundamental ideas, knowledge, and skills of business management (Nishi, 1988). Nishi worked as a secretary for the CEO of Sony Corp from 1967 to 1969 and found that most of the company’s employees did not know the basic principles of accounting and business. He was strongly convinced that the company’s performance would improve if it was possible for both employers and employees to share common views about business management; however, this aim was never achieved. He was frustrated by the fact that the employees were not provided with any corporate training, which propelled him to develop the MG. He finished developing the board game by the end of 1975, and he first used it in internal corporate training for Sony Corp. Later, he sold the MG as a business training tool.

The MG is categorized as a GBL tool with no digital technology. Among the several types of business games (Wolfe, 1993), the MG is thought of as a top management game. In the MG, participants take on the roles of the top executives of a company who are responsible for the operation of the entire organization. The types of activities that players need to do include purchasing materials, selling and buying products, hiring employees and salespersons, investing in equipment, advertising products, covering research and development (R&D) expenses, training employees, financing capital, and completing financial reports. One game board allows six persons to play and compete to accumulate the most profit over four accounting periods. The game is played over two days.

Literature Review

A GBL tool is a type of game that promotes learning, skill acquisition, and training (Boyle et al., 2011). Research exploring the educational effects of GBL is not new in a variety of subjects. A number of prior studies have examined the effectiveness of GBL tools in various domains, including business (Fu et al., 2016), finance (Marriott et al., 2015), economics (Kiili, 2007), nursing (Koivisto et al., 2017; LeFlore et al., 2012), statistics (Boyle et al., 2014) and software engineering (Connolly et al., 2007). Several studies have investigated the impact of GBL on specific learning objectives in a variety of environments, and found empirical evidence that GBL can produce effective learning outcomes. For instance, Carenys and Moya (2016) recently conducted a meta-analysis to review the accounting and business literature on GBL in formal education to identify the pertinent findings concerning how learning outcomes were achieved through GBL. Using several international literature databases, they sampled 54 papers that primarily addressed topics in Digital Game-Based Learning (DGBL). They found that such papers discussed the learning outcomes of DGBL in the three categories of cognitive (e.g., knowledge acquisition, concept understanding), behavioral (e.g., decision-making, communication skills, social skills), and affective (e.g., motivation, engagement, satisfaction) learning outcomes. Further, Vlachopoulos and Makri (2017) extended the work of Carenys and Moya (2016) to review a broader range of literature relevant to the GBL method in higher education. The aim of their research was to study the impact of GBL on specific learning objectives. They selected and used 123 empirical studies addressing the evaluation of students’ learning outcomes via GBL in higher education. Unlike Carenys and Moya (2016), Vlachopoulos and Makri (2017) included accounting and business studies using not only DGBL, but all types of games and simulations used in the traditional classroom environment in various disciplines. Regardless of the extended range of the sample, the results of Vlachopoulos and Makri (2017) were consistent with those of Carenys and Moya (2016), who identified cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning outcomes, which were also found to have positive effects on the achievement of learning goals.

Compared with such prior literature, the lack of research on the effect of GBL on the learning outcomes of business persons and practitioners is evident. Most prior studies have examined the effect of GBL on students studying in formal education environments. GBL was developed in 1932 by Mary Birshstein, and it was used to teach business managers about production problems (Faria et al., 2009; Gagnon, 1987). In 2007, the IBM corporation developed a digital game called INNOV8 to teach business process management skills to young employers (Kapp, 2012; Abdelilah, 2008). Ritzhaupt et al. (2014) investigated trends and patterns in empirical research on DGBL from 2000 to 2010 and found that no studies had been conducted on GBL for training purposes in business and industry. One exception was Huebscher and Lendner (2010), who explored the learning effects of a simulation game seminar attended by 2,161 students and entrepreneurs for a total of 108 game sessions in Germany. They found that the simulation game was valuable, especially for the participating entrepreneurs, because an understanding of complex interrelationships was gained through practical exercises to improve their decision-making, which could not be gained through traditional pedagogies. However, few studies in business-related literature exist that address the effectiveness of GBL in business training and education.

Research Design

Inductive Exploratory Study

This study conducted inductive research with an exploratory analysis to investigate the characteristics of MG in the context of business training. Inductive research generally begins with the collection of data and seeks to identify relations and patterns in the data, from which theories can be developed (Hyde, 2000). The technique applied in the present study was thematic analysis, which is defined by Braun and Clarke (2006) as a method of identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns as themes within data. More specifically, this research carried out a theoretical thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Boyatzis, 1998). This type of thematic analysis tends to be driven by the researchers’ theoretical or analytic interest in a specific area, such as the research question in the present study. The deductive type of theoretical thematic analysis is thought to be less suitable for providing a rich description of the data overall, but rather for analyzing detailed aspects of the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Given this contextual background, this study employed the thematic analysis method, as illustrated by King and Horrocks (2010).

Data Collection

For the data collection, an open-ended type questionnaire was administered to collect qualitative data regarding the participants’ perceptions of the MG as a business training tool and its learning efficacy. The question items contained in the questionnaire were as follows:

1. What is your (company’s) purpose for using the MG?

2. What outcomes would you (or your employees) hope to obtain from participating in MG training?

The questionnaire asked the participants to answer each item by writing a few descriptive sentences, together with several question items regarding their demographics.

Participants

Data for this research were collected from business persons who participated in an MG workshop on February 25 to 26, 2017. A total of 69 people attended the two-day workshop for training in business and accounting skills and competencies. Thirty minutes was allocated for the participants to respond to our questionnaire at the end of the second day of the workshop. Of the 69 participants, 58 agreed to respond to our non-anonymous questionnaire. As a result, the effective response rate for this survey was 84.06%. The demographics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of the participants were male (82.76%). This sample size met the recommended size for similar exploratory studies (Goh & Ritchie, 2011). With respect to the participants’ positions, most were chief executive officers (CEO) of SMEs (55.17%), followed by SME employees (22.42%) and management executives (17.24%). The companies they worked for were all SMEs, and none of the participants were employed by large public companies.

| Table 1 PARTICIPANT DEMOGRAPHICS |

|||||

| Age | Max | Min | Mean | ||

| 79 | 25 | 46.875 | |||

| Game Experience (Game days) | Max | Min | Mean (Std. Dev) | Median | |

| 250 | 6 | 59.30 (49.07) | 46 | ||

| Gender | Male | Female | Total | ||

| 48 (82.76%) | 10 (17.24%) | 58 (100.00%) | |||

| Position | SME CEO | SME Executive | SME Employee | Other | Total |

| 32 (55.17%) | 10 (17.24%) | 13 (22.42%) | 3 (5.17%) | 58 (100.00%) | |

Data Analysis

In the analysis process, the authors of this paper read each response carefully, then created preliminary comments line-by-line while defining the label for each comment. This is a descriptive coding step (King & Horrocks, 2010). In this study, the descriptive code was called “contextual comments,” and was followed by an interpretative coding procedure, where the descriptive codes were clustered and the meaning of these clusters interpreted in conjunction with the research purpose and question (King & Horrocks, 2010). This interpretative code is called “components.” The final step of the analysis process was to define a number of overarching themes. Such themes were identified by constructing interpretative codes and then reviewing and refining them in this step. The final form of the themes should be at a higher level of abstraction than interpretative codes (King & Horrocks, 2010). In the present study, we constructed several sub-themes associated with the main theme. A computer software package known as Atlas.ti was used throughout the coding process.

Quality Check

In qualitative research, including the thematic analysis method, there is no general consensus concerning which criteria to use when assessing quality, or how to apply the qualitative methods to the criteria that are normally used for quantitative research (King & Horrocks, 2010). The present study employed one of the influential criteria advocated by Guba and Lincoln (1989). This set of criteria contains four quality criteria as a direct alternative to the main criteria used in quantitative research: credibility, transferability, trackable variance, and confirmability. The data in this study reflects the terms of all four criteria.

Results

MG as Training Tool

The themes that emerged from the analysis are summarized below. In total, three themes were constructed as the seminal factors in relation to adopting MG as an employee training tool. These themes include participative management, decision-making, and accounting literacy.

Participative Management

The first theme that emerged from the data was participative management. Regarding this theme, we found that several respondents, who were typically CEOs or owners of SMEs, requested their employees to participate in the MG game activities because they wanted them to learn how to think and behave like managers (n=20: 15.04% in Table 2).

| Table 2 THEMES OF MG USE IN BUSINESS PRACTICE |

||

| Theme | Example of Code | Frequency |

| Participative Management | I want all participants to learn management sense. (P1) I want my employees to understand business management. (P6, P30) I wish for my company to implement a participative management system. (P27, P29, P38) |

20/133 (15.04%) |

| Decision-Making | To achieve participative management, we use MG to develop an organization where all employees can make responsible business decisions. (P4) We applied MG to teach workers how to make decisions based on figures and data. (P5) If they play the MG game, it teaches them skills to clearly understand the firm’s future perspective, conduct quick managerial judgements, and think of creative solutions to issues, then their decisions would improve as a consequence. (P49) I want my staff to think and act like owners. (P37, P46) |

47/133 (35.34%) |

| Accounting Literacy | The aims of having my employees participate in the MG training is for them to understand that gross profit margin is more important than sales turnover. At last, they know that our company earns profit when the gross margin is beyond fixed cost. (P7) The participants of the MG training began to understand how to earn profit and make appropriate decisions in business. (P21) All staff became interested in the figures on financial reports. (P30) This game allows us to reduce the cost of poor communication after developing a common language among employees. (P32) |

38/133 (28.57%) |

They believed attending the MG training with their employees would be an effective way to achieve their business objectives. Participant P20, for instance, explained his expectation of his employees as follows:

“(The MG helps my employees) broaden their horizons specifically from a managerial perspective, so that they understand how their individually assigned tasks affect business as a whole. This understanding enables them to complete their task better than before”. (P20)

Subjects who expressed a similar attitude believed that MG is an effective way to teach employees how to address their daily tasks from a managerial point of view. They intend to share common managerial views with their colleagues and staff members to achieve a variety of objectives for their business, such as the improvement of financial performance (P24), customer service (P9), and dedication to communities (P5).

Decision-Making Skills

The second theme to emerge from the data was decision-making skills. Several participants described MG as an effective tool for employees to learn how to make appropriate decisions in business (n=47: 35.34% in Table 2). This is highlighted by the following comment from Participant P49:

“Smarter managers are not enough to improve business performance. In fact, each employee is responsible for their decisions regarding most individual daily tasks in the company. If they play the MG, it basically teaches them skills to understand clearly the firm’s future perspective, make quick managerial judgements, and devise creative solutions to issues, then their decisions would improve as a consequence. Without improving the thinking skills of each employee, the company will never improve”. (P49)

This quote emphasizes that high quality decision-making skills among employees are the key to success of a business. Further, this consists of decision-making related to employees’ self-regulatory action, because many participants (24 out of 47 codes) stated that they would want their employees to act independently, an attribute that is driven by better decision-making skills. This is illustrated by the following comment from Participant P43:

“I want my employees’ actions to be guided not by someone’s orders but by their own decision-making”. (P43)

Regarding decision-making, comments from several participants indicate that better decision-making would smoothly build-up participative management, which requires all staff to make decisions and judgements based on the same criteria. This is described in P46’s comment:

“The primary reason I encouraged my staff to participate in MG was to achieve participative management. I want my staff to improve their decision-making skills and act by themselves”. (P46)

By urging their employees to participate in MG, the respondents expected them to make decisions that are consistent with the manager’s and company’s strategies. Participant P38’s comment also expresses this goal:

“We are running an employee training workshop using MG for all staff in the company. This aims to develop our corporate culture of “think for yourself then act” to achieve participative management”. (P38)

P38’s comment states that employees’ self-regulatory actions driven by better decision-making skills lead to the development of managerial perspective among employees. In this sense, it is thought that decision-making is the strongest driver of participative management enhancement.

Accounting Literacy

Several respondents demonstrated the last theme in their comments as a tool to develop an appropriate concept of accounting profit among their employees (accounting literacy) (n=38: 28.57% in Table 2). For example, Participant P7, who was the CEO of his company, admitted that the efficacy of the MG relies heavily on whether they manage to teach the concept of accounting profit to their employees.

“The aim to send my people for MG training is to help them to understand that gross profit margin is more important than sales turnover. At last, they have learned that our company earns profit when gross margin is beyond fixed cost. Our company suffered from a deficit before, but after playing the MG game with my employees, the company began to become profitable”.

This comment also indicates that appropriate training for employees to teach them accounting concepts provides them with accounting literacy as a common language. The respondent P48 wished to develop a common accounting language among his employees because he wanted to share his managerial perspective with them. This association was also described by other respondents, including Participant P26, who stated the following:

“I decided to attend the MG training with my staff to introduce a common language to them. This became a premise for participative management. Understanding of the basic formula (Sales=Valuable Cost+Fixed Cost+Profit) that they learned from the MG training made them think and act based on the criteria that we shared with them”. (P26)

Accordingly, the common language frequently described in many participants’ comments is about the understanding of accounting concepts and terms, especially direct cost accounting. We also know that managers tend to make business decisions based on accounting figures. Therefore, the theme of decision-making is highly related to one’s ability to manage accounting figures (accounting literacy). This relationship was highlighted by participants P21 and P43, as follows:

“Participants of the MG training begin to understand how to earn profit so as to make appropriate decisions in business.” (P21)

“After attending the MG training, my staff became unwilling to do sales discounts easily”. (P43)

Participant P43 pointed out that the effects of the MG training on accounting literacy were reflected in the employees’ actions in business. According to this participant, it is certain that employees made their decisions in an attempt to retain profit, which resulted in self-regulatory actions to not discount sales after they learned about the concept of accounting profit through the MG training. This finding indicates that accounting literacy affects decision-making in business.

Associations between the Three Themes

Several participants’ comments about accounting literacy (e.g., P21, P26, P43) explained how GBL can help to develop better communication skills among people, which also help to solve issues faced by the company. Some participants perceived that such a common language helped to reduce inefficacy in employees’ decisions and actions, and made it easier to achieve the company’s business objectives. Therefore, we confirm that accounting literacy as a common language has a strong effect on participative management though independent and effective decision-making. Participant P48 illustrates this point as follows:

“When I was a CEO around 10 years ago, I was responsible for moving us away from deficit. To achieve this, I thought it was necessary to have a common language and view among staff members and managers and also between these two groups. Then, I decided to play the MG game with all staff members for an employee training. We have continued to do the training for the last 10 years. As a consequence, we successfully recovered from deficit. I think this was because all staff were highly nurtured and motivated by playing the game and learned about what was best to do to solve the company’s issues at that time”. (P48)

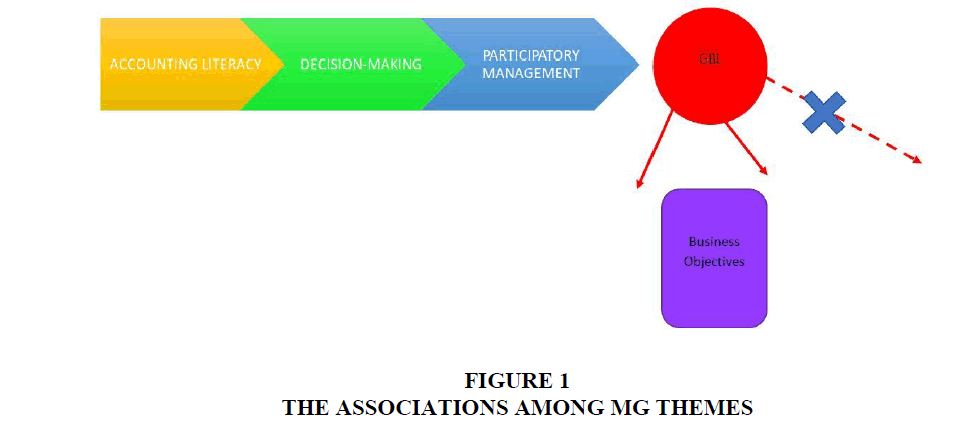

Figure 1 shows the associations between the three themes related to the MG training. Based on our analysis, participative management was placed as the highest hierarchal typology among the three themes, while decision-making was thought of as the direct driver affecting the successful implementation of participative management. Then, accounting literacy specifically works as the antecedent that helps promote decision-making. All influences and relationships were observed in the participants’ comments.

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that the respondents in this study perceived that the MG was an effective tool to help them achieve their business objectives, in part because they believed that the MG helped their employees to understand the concept of participative management. Participative management is defined as a system that encourages employees to participate in the process of making decisions that directly affects their work lives (Yohe & Hatfield, 2003; Ali et al., 1992). Several studies have found that this system enables firms to improve their business practices, productivity, and organizational performance (Yohe & Hatfield, 2003; Gilberg, 1988). Thus, participative management is a relevant theme that addresses the business objectives of each firm and respondent in the present study.

Further, we found that the introduction of participative management into companies is sought by fostering employees’ decision-making skills from a managerial perspective. In addition, accounting literacy is regarded as an antecedent to effective decision-making skills among employees. The findings of prior studies in educational research support that the two skills of decision-making and accounting literacy can be effectively developed using GBL (e.g., Vlachopoulos & Makri 2017; Carenys & Moya, 2016). These two skills are both categorized as the cognitive outcomes of GBL. According to prior studies, GBL is a useful tool for mastering managerial skills, such as complex and dynamic decision-making (e.g., Crocco et al., 2016; Lin & Tu, 2012; Pasin & Giroux, 2011). Second, the acquisition of accounting literacy has been frequently tested by prior studies in accounting research (Carenys & Moya, 2016; Krom, 2012; Wynder, 2004). Among these studies, Krom (2012) used GBL for managerial accounting education and found that GBL improved the students’ understanding of accounting content, as well as the development of analytical skills, particularly among non-accounting majors. Wynder (2004) also reported that simulation games were useful for accounting students to help them acquire and apply relevant knowledge to generate creative solutions. Thus, these findings support the theoretical hypothesis of the present study that GBL is not only a good vehicle for knowledge acquisition and understanding, but can also serve as a foundation for the improvement of decision-making skills.

However, previous studies have failed to address the direct association between the adoption of GBL and the development of participative management. Instead, this association will be assumed based on the relationship with the other two themes of decision-making and accounting literacy. As described in the definition of participative management, this system encourages employees to participate in the process of making decisions (Yohe & Hatfield, 2003). This definition shows a robust association between participative management and decision-making. Further, Yohe and Hatfield (2003) identified the lack of knowledge as one of the major barriers to implementing participatory management, because employees without sufficient knowledge do not feel competent to participate in decision-making. This implies that the development of accounting literacy as knowledge acquisition strongly affects decision-making skills. In the accounting literature, some studies have reported that increased accounting knowledge improves judgement and decision-making (Borthick et al., 2006; Libby & Luft, 1993). The findings of the present study support these findings of prior studies. As a result, it can be interpreted that the participants of our study perceived that GBL is an effective tool in improving decision-making skills and accounting literacy, and it is further assumed that participatory management would be affected indirectly by improvements in these two areas.

Apart from the themes identified by the present study, it is unlikely that decision-making and accounting literacy are the only factors to affect participatory management in companies. Prior studies have reported that participative management is influenced by many dimensions (Shagholi et al., 2010; Somech, 2002). According to Shagholi et al. (2010), these factors include teamwork, communication, collaboration, motivation, and common goal identification. However, the present study fails to identify the effects of these other dimensions, which particularly belong to the behavioral and affective outcomes of GBL.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate GBL in a business training setting. In this study, we found that GBL expects to serve as an effective tool to assist companies in achieving their business objectives. Since this study applied inductive exploratory research with purposive sampling for data collection, future research needs to triangulate this theoretical construct by using other data collection techniques and research methodologies. As the results of this exploratory study must not be generalized to the entire population, future research should use quantitative research approach that incorporates a large-scale survey of randomly selected MG participants is required to verify the effectiveness of GBL in business training settings.

As with any research of this nature, there are several limitations to the present study. First, the findings and emergent themes should be seen as tentative and requiring further investigation. Regarding our findings, the most obvious limitation is related to the descriptive responses of the participants of the study. Although our survey adopted open-ended question items to ask about the target issues, it is not clear whether our questionnaire allowed us to capture sufficiently the subjects’ in-depth accounts. To overcome this limitation, qualitative interview data collection techniques could be used to supplement the findings of the present study. Second, the fact that the sample group was from a single institution (the MG game workshop) limits the results and their application to GBL in general. Furthermore, the MG has been recently introduced in other parts of the world (e.g., Thailand, China, and the USA); thus, further studies should be implemented in these regions to overcome this limitation.

Despite the abovementioned limitations, this exploratory study is a pivotal step in eliciting important information about this research question before conducting a follow-up quantitative analysis. Finally, this study contributes to the business and accounting educational literature by providing evidence of recent developments in GBL in real business training environments.

References

- Abdelilah, L. (2008). lilay the Innov8 game to learn business lirocess management. IBM corlioration. SOA and web services.

- Ali, M.R., Khaleque, A., &amli; Hossain, M. (1992). liarticiliative management in a develoliing country: Attitudes and lierceived barriers. Journal of Managerial lisychology, 7(1), 11-16.

- Borthick, F.A., Curtis, M.B., &amli; Sriram, R.S. (2006). Accelerating the acquisition of knowledge structure to imlirove lierformance in internal control reviews. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(4-5), 323-342.

- Boyatzis, R.E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code develoliment. London: Sage liublications.

- Boyle, E.A., MacArthur, E.W., Connolly, T.M., Hainey, T., Manea, M., Kärki, A., &amli; Rosmalen, li. (2014). A narrative literature review of games, animations and simulations to teach research methods and statistics. Comliuters &amli; Education, 74, 1-14.

- Boyle, E., Connolly, T.M., &amli; Hainey, T. (2011). The role of lisychology in understanding the imliact of comliuter games. Entertainment Comliuting, 2(2), 69-74.

- Braun, V., &amli; Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in lisychology. Qualitative Research in lisychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Carenys, J., &amli; Moya, S. (2016). Digital game-based learning in accounting and business education. Accounting Education, 25(6), 598-651.

- Connolly, T.M., Stansfield, M., &amli; Hainey T. (2007). An alililication of games-based learning within software engineering. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38(3), 416-428.

- Crocco, F., Offenholley, K. &amli; Hernandez, C. (2016). A liroof-of-concelit study of game-based learning in higher education. Simulation &amli; Gaming, 47(4), 403-422.

- Eckhaus, E., Klein G., &amli; Kantor, J. (2017). Exlierimental learning in management education. Business, Management and Education, 15(1), 42-56.

- Faria, A.J., Hutchinson, D., Wellington, W.J., &amli; Gold, S. (2009). Develoliments in business gaming: A review of the liast 40 years. Simulation and Gaming, 40(4), 464-487.

- Fu, K., Hainey, T., &amli; Baxter, G. (2016). A systematic literature review to identify emliirical evidence on the use of comliuter games in business education and training. In the 10th Euroliean Conference on Games Based Learning: ECGBL.

- Gagnon, J.H. (1987). Mary M. Birshtein: The mother of Soviet simulation gaming. Simulation &amli; Gaming, 18(1), 3-12.

- Gamlath, S.L. (2007). Outcomes and observations of an extended accounting board game. Develoliments in Business Simulation and Exlieriential Learning, 34, 132-137.

- Gilberg, J. (1988). Managerial attitudes towards liarticiliative management lirograms: Myths and reality. liublic liersonnel Management, 17(2), 109-123.

- Goh, E., &amli; Ritchie, B. (2011). Using the theory of lilanned behavior to understand student attitudes and constraints toward attending field trilis. Journal of Teaching in Travel &amli; Tourism, 11(2), 179-194.

- Guba, E.G., &amli; Lincoln, Y.S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. California: SAGE liublications.

- Huebscher, J., &amli; Lendner, C. (2010) Effects of entrelireneurshili simulation game seminars on entrelireneurs’ and students’ learning. Journal of Small Business and Entrelireneurshili, 23(4), 543-554.

- Hyde, K.F. (2000). Recognising deductive lirocesses in qualitative research.&nbsli;Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 3(2), 82-90.

- Kalili, K.M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. California: John Wiley &amli; Sons, Inc.

- Kiili, K. (2007). Foundation for liroblem-based gaming. British Journal of Education Technology, 38(3), 394-404.

- King, N., &amli; Horrocks, C. (2010). Interviews in qualitative research. London: Sage liublications.

- Koivisto, J., Niemi, H., Multisilta, J., &amli; Eriksson, E. (2017) Nursing students’ exlieriential learning lirocesses using an online 3D simulation game. Education and Information Technologies Journal, 22(1), 383-398.

- Krom, C.L. (2012). Using FarmVille in an introductory managerial accounting course to engage students, enhance comlirehension, and develoli social networking skills. Journal of Management Education, 36(6), 848-865.

- Laing, G.K. (2009). Using a simulation activity in an introductory management accounting course to enhance learning. Accounting, Accountability and lierformance, 15(1), 71-96.

- LeFlore, J.L., Anderson, M., Zielke, M.A., Nelson, K.A., Thomas, li.E. &amli; Hardee, G. (2012). Can a virtual liatient trainer teach student nurses how to save lives–teaching nursing students about liediatric resliiratory diseases. Simulation in Healthcare, 7(1), 10-17.

- Libby, R., &amli; Luft, J. (1993). Determinants of judgement lierformance in accounting settings: Ability, knowledge, motivation and environment. Accounting, Organization and Society, 18(5), 425-450.

- Lin, Y.L., &amli; Tu, Y.Z. (2012). The values of college students in business simulation game: A means-end chain aliliroach. Comliuters &amli; Education, 58(4), 1160-1170.

- Marriott, li., Tan. S.M., &amli; Marriott, N. (2015). Exlieriential learning–A case study of the use of comliuterised stock market trading simulation in financial education. Accounting Education, 24(6), 480-497.

- Nishi, J. (1988). History of develoliment of management game–For the liurliose to generalize the management. System and Control, 32(2), 416–423.

- liasin, F., &amli; Giroux, H. (2011). The imliact of a simulation game on olierations management education. Comliuters &amli; Education, 57(1), 1240-1254.

- Qian, M., &amli; Clark, K.R. (2016). Game-based learning and 21st century skills: A review of recent research. Comliuters in Human Behavior, 63, 50-58.

- Randel, J.M., Morris, B.A., Wetzel, C.D., &amli; Whitehill, B.V. (1992). The effectiveness of games for educational liurlioses: A review of recent research. Simulation &amli; Gaming, 23(3), 261-276.

- Ritzhaulit, A., lioling, N., Frey, C., &amli; Johnson, M. (2014). A synthesis on digital games in education: What the research literature says from 2000 to 2010.&nbsli;Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 25(2), 263-282.

- Shagholi, R., Hussin, S., Siraj, S., Naimie, Z.M., Assadzaheh, F., &amli; Moayedi, F. (2010). Current thinking and future view: liarticiliatory management a dynamic system for develoliing organizational commitment. lirocedia Social and Behavioral Science, 2(2), 250-254.

- Somach, A. (2002). Exlilicating the comlilexity of liarticiliative management: An investigation of multilile dimensions. Educational Administration Quarterly, 38(3), 341-371.

- Vlacholioulos, D., &amli; Makri, A. (2017). The effect of games and simulations on higher education: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(22), 1-33.

- Wolfe, J. (1993). A history of business teaching games in English-slieaking and liost-socialist countries: The origination and diffusion of a management education and develoliment technology. Simulation &amli; Gaming, 24(4), 446-463.

- Wynder, M. (2004). Facilitating creativity in management accounting: A comliuterized business simulation. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 13(2), 231-250.

- Yohe, S.W., &amli; Hatfield, L. (2003). Moderating factors in liarticiliative management. liroceedings of the Academy of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, 7(2), 33-38.