Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 1

Modern Problems of the Law Enforcement Practice of the Principle of Disarmament in International Security Law

Alibek Bolat, Kazakh-Russian International University

Sholpan Saimova, Kazakh-Russian International University

Dauren Bekezhanov, Zhetysu University named after I. Zhansugurov

Dinara Ashimova, Zhetysu University named after I. Zhansugurov

Makpal Konysbekova, Zhetysu University named after I. Zhansugurov

Gulim Zhakupova, Zhetysu University named after I. Zhansugurov

Citation Information: Bolat, A., Saimova, S., Bekezhanov, D., Ashimova, D., Konysbekova, M., & Zhakupova, G. (2022). Modern problems of the law enforcement practice of the principle of disarmament in international security law. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(1), 1-19

Abstract

This scientific article reflected the main aspects of international security law and the specifics of the legal support of the mechanism and principle of disarmament to preserve and maintain peace and security of people. In addition, the article provides a legal analysis of disarmament as a principle of modern international law. The study of the law enforcement practice of the international legal doctrine and the current international legal and internal acts of states led to the conclusion that the principle of disarmament has not been formed in modern international law. It can only be asserted about the formation of the principle of limiting arms, which is closely linked with one of the principles of international humanitarian law - the principle of limiting the means and methods of conducting military operations. At the same time, disarmament is essential for the maintenance of international peace and security. On the other hand, military cooperation between states in accordance with the principles of international law is an important component for ensuring national, regional and universal security.

Keywords

Disarmament, Legal Non-Proliferation, Legal Regulation, International Security, Legal Guarantee, Law Enforcement Practice, Principle.

Introduction

Disarmament is the complete or limited restriction of the armaments of a state or a certain territory. Disarmament is regulated by international agreements. It includes the state's armed forces, military fortifications and bases, military production, etc. is prohibited in whole or in part.

Although the current international and global situation is conducive to disarmament, the implementation of nuclear disarmament requires a comprehensive and genuine struggle of the world community.

Today, disarmament and arms control are one of the most effective international legal instruments for peacekeeping and conflict prevention.

In 2019, global military spending exceeded $ 1.9 trillion. At the end of 2020, this amount will be equivalent to $ 2.3 trillion. The topical issues of world culture of peace and the maximum reduction of armaments have never been so said.

The problems of ensuring international security are more urgent than ever in our time. International relations are characterized by instability. And today we can definitely say that the «cold war» has not ended, and not only continues, but is also developing. Is it possible to ensure international security at this stage of development of not so «friendly» relations? The author of this article will try to answer this question.

International security law is a system of principles and norms governing military-political relations between states and other subjects of international law in order to prevent the unauthorized use of military force, fight international terrorism, and limit and reduce arms.

This branch of international law is based primarily on the UN Charter and many other treaties that restrain the nuclear arms race and limit the build-up of arms in qualitative and quantitative terms (the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Siting on the Bottom of Seas and Oceans and in Its Subsoil of nuclear weapons and other types of weapons of mass destruction 1971, Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapons Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water 1963, Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty 1996, Treaty between Russia and the United States on the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms 1993 etc.) (Bobrov, 1964).

International security law is based on the principles of the non-use of force and the peaceful resolution of disputes. These principles are enshrined in international acts and reflected in the theory of international law, but are they in effect at the moment?

After the end of World War II, the spheres of influence in Europe were divided into two zones - the countries that were under the influence of the USSR, and the countries that were against this influence. The Cold War began. It resulted in the formation in 1949 of the North Atlantic Alliance (NATO) and the Warsaw Pact Organization (1955).

As a result of the liquidation of the Warsaw Pact Organization, which opposed the NATO bloc, and then the collapse of the USSR, stability, peace and security in Europe ceased to exist. Now we see the process of the expansion of the NATO bloc to the East and its gradual approach to the borders of the Russian Federation, which indicates a clear open confrontation. Accordingly, as spheres of influence approaching the borders of the Russian Federation in their internal political cauldron, these borders are also influenced by the former countries of the USSR.

It can be stated that the characteristic features of modernity are: a change in the nature and hierarchy of threats to international peace with a shift towards internal conflicts; the increasingly frequent intervention of third forces in internal conflicts; domestic violence; the growth of transnational threats - terrorism, organized crime, drug trafficking (Derigizalova, 2005).

It is impossible not to see that the modern world is objectively multipolar, and a number of countries advocating the provision of a single international legal order based on the goals and principles of the UN Charter do not want to put up with this situation. Kazakhstan also belongs to these countries.

Another problem is nuclear disarmament. Although the Republic of Kazakhstan is an authoritative country in the issue of disarmament of all types of weapons, the international community is forcing our country to call on all countries to strengthen the application of the principle of disarmament to maintain global stability and order. After all, treaties that are supposed to contain a powerful minority of countries simply do not work as effectively as they should.

In 2007, the authoritative American magazine The Wall Street Journal published an article entitled A World Free of Nuclear Weapons. In this article, it was argued that the concept of nuclear deterrence that existed during the Cold War collapsed. In the modern world, the number of countries possessing nuclear weapons is growing. Of particular concern is the possibility of nuclear weapons falling into the hands of terrorists. In such conditions, mankind must completely abandon nuclear weapons. Since then, the trend has not changed, but on the contrary makes the situation that there is now to make sure that international treaties need a strong support for their successful effectiveness (Chekov, 2013).

However, one should recognize the fact that complete nuclear disarmament is impossible for two reasons: 1) pursuing a policy of double standards in nuclear disarmament. There is no guarantee that if the parties fulfill the treaty on complete nuclear disarmament, one of the parties will not violate it. It is impossible to fully control the destruction of nuclear stockpiles, and no one wants to believe the opponent's word of honor; 2) as mentioned above, nuclear weapons are a defense against military attack. Perhaps my position will seem anti-American, but we can observe this in specific examples of US invasion of other countries. Where there were no nuclear weapons, the Americans were free to carry out their operations. This policy did not work with Iran, because there is reason to believe that Iran is developing or has already developed its own nuclear weapons. Therefore, the United States is content with only economic sanctions against this state.

For a qualitative solution to this deadlock, reminiscent of the ouroboros, two things should be understood: 1) disarmament requires huge finances, which in an era of economic crises is not the most profitable business for a number of many states; 2) Public opinion - this category affects several populations but also governments of countries that think that the general conflict and problems in this area do not concern them, thus they do not want to be participants in solving this problem. Accordingly, if these two fundamental problems are solved, all law enforcement practice will act as it was originally intended.

As already noted, today the task of complete disarmament is illusory. Ideally, a world without nuclear and other types of weapons is the best prospect for all countries, but not every state is ready to take such a risky step. There is no alternative substitute for nuclear and other mass destruction weapons that can establish a strategic balance. Losing nuclear weapons, some countries are directly under the threat of attack by other states that have a larger and more trained armed army. Until maximum trust is achieved between states, complete total disarmament is a dream for many years, and perhaps for centuries.

In its scientific direction of research, the following problems can be identified that exist due to the ineffective application of the principle of disarmament in law enforcement practice:

1. The appearance at the end of the 20th century of weapons of mass destruction and their spread across the planet;

2. Huge accumulated world reserves of modern weapons capable of repeatedly destroying the entire population of the planet;

3. The constant growth of military spending;

4. The constant growth in the scale of the arms trade;

5. Increasing unevenness in the level of socio-economic development between developing and developed countries, aggravation of energy, raw materials, territorial and other problems, leading to an increase in the possibility of interstate conflicts, etc.

6. The still ongoing arms race.

The latter problem in our modern society is exacerbated as never before in an extremely active and purposeful manner. For example, an arms race and its real danger are assessed by the following circumstances:

1. The huge scale of progress in military technology, the emergence of fundamentally new weapons systems. The line between the weapon for whom it is intended is erased;

2. Political control over the development of nuclear missile weapons is becoming more difficult;

3. The line between nuclear and conventional war is being erased as a result of progress in the creation of modern means of destruction;

4. The interests of people working in the military-industrial complex are in defense of the arms race;

5. The production of weapons ensures the geopolitical interests of states, so the problem is faced with their contradictions (Alves, 2013).

Methodology

The methodological basis of the article is general and special methods and techniques of scientific knowledge. The normative-dogmatic method is used in the study of international and domestic legal acts regulating the issue of disarmament.

The epistemological method is used to clearly define the concept of "disarmament". The monographic method is used when considering the concept of "Law enforcement practice of the principle of disarmament" in the works of scientists in this area. The comparative legal method allows you to compare the state of affairs in countries with a high index of weapons that consolidate the order of disarmament to maintain peace and security. The grouping method helps to determine the conditions that must be met for the implementation of the principle of disarmament in modern times. The logical and legal method is used to interpret the concepts of "weapons of mass destruction" and "nuclear weapons". The generalization method is used to formulate appropriate conclusions and proposals.

The scientific and theoretical basis of the article is the scientific works of specialists in the field of international law and international security law, criminal law and other branches of interdisciplinary legal sciences. The normative base of the study is the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan, laws, bylaws, draft laws and other international normative legal acts that determine the legal foundations of world disarmament to ensure the world security of states from the general destruction of each other.

Results and Discussion

Today you can see in numbers the problems associated with non-observance of the disarmament principle, as well as some historical aspects.

If you give some numbers and examples on this issue, then:

1. According to the calculations of specialists, died during the wars: 17th century - 3.3 million people, 18th century - 5.4 million, 19th century - 5.7 million, 1st world war - 20 million, 2nd world war - 50 million;

2. WORLD military spending exceeds the income of the poorest half of humanity and amounts to more than 1.9 trillion dollars a year; this is significantly more than military expenditures during the Second World War;

3. US military spending for 2019 - $ 732 billion;

4. The arms trade now reaches 35-40 billion dollars a year;

5. Leading arms suppliers - USA, Great Britain, France, Russia;

6. The cost of importing weapons and equipment in developing countries exceeds the cost of importing all other goods, including food.

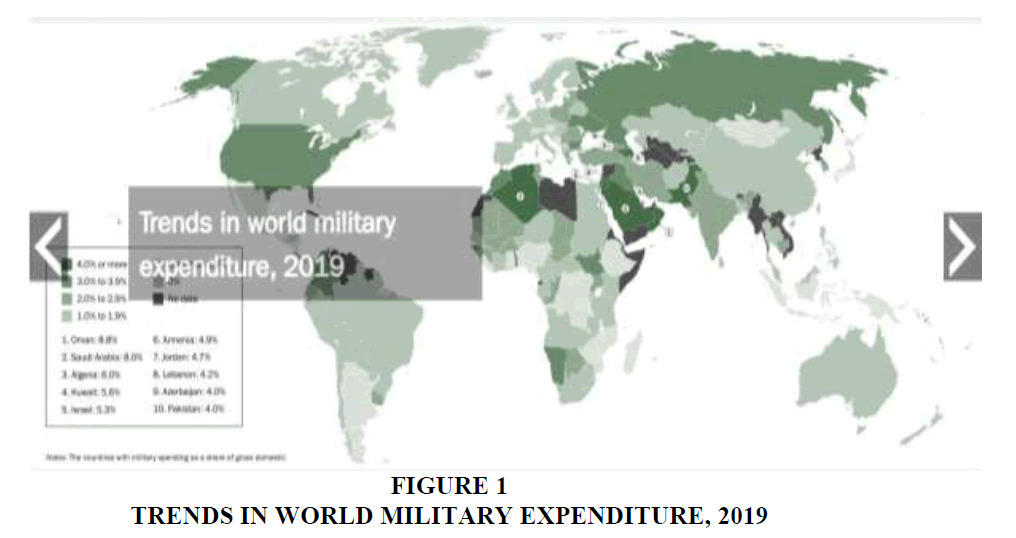

As you can see the numbers are growing both in regional and international terms. The trend is growing from year to year, and this is extremely detrimental to the future solution of the disarmament problem. This is also explained by the fact that there is no international agreement on the control of military spending between the countries (Figure 1), which means there is no law enforcement practice (Madsen, 2015).

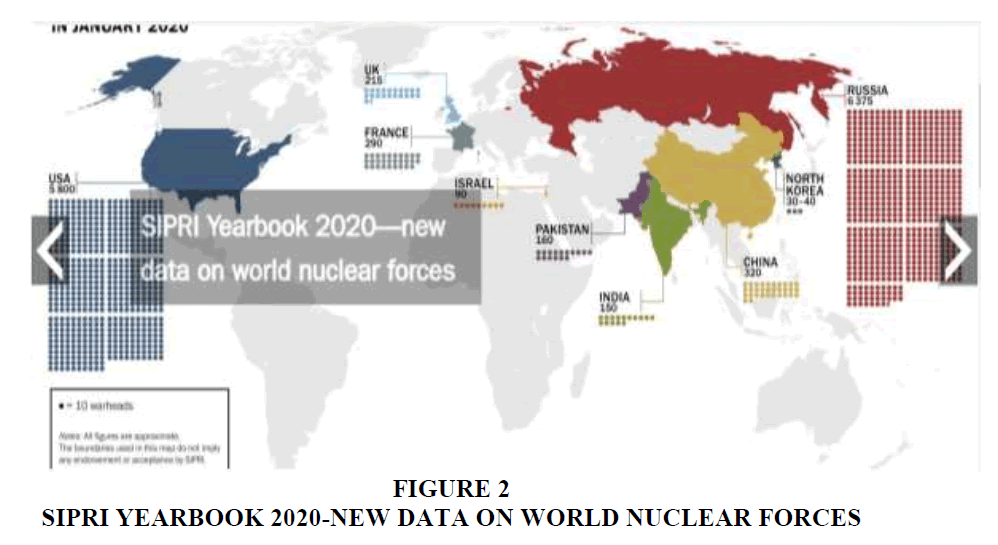

To solve the problem of reducing the risk of a possible exchange of nuclear strikes between nuclear weapons, issues of control over nuclear weapons are of paramount importance. Today, this area is limited by bilateral agreements between Russia and the United States, thecurrent ones of which include the Russian International Affairs Council Treaty, the START III Treaty and the 1991 unilateral initiatives to reduce tactical nuclear weapons (Figure 2).

Recognized international experts in the field of strategic weapons believe that «with the end of the ideological conflict between Moscow and Washington and the global confrontation between the two systems, there is a theoretical» possibility and political need to replace mutual nuclear deterrence with a new, more positive model of interaction between Russia and the United States in the nuclear sphere. The mechanism of positive military-political interaction is proposed to be embodied in the model of mutual guaranteed security, which provides for minimizing mutual nuclear risks by both lowering the level of combat readiness of strategic nuclear forces and adopting a counter-value strategy (reorientation of the US strategic offensive forces and strategic nuclear forces Russia from protected military targets to civilian ones), which will allow completely to abandon the concept of a retaliatory strike, which a priori carries with it increased risks of accidentally unleashing a nuclear war.

This counter-value strategy has another advantage. If the nuclear forces of one side are clearly intended only for a counter-value response, and not a preemptive counter-force strike, then there is no need to constantly keep all of them in a state of maximum combat readiness. This not only encourages the other side to abandon the concept of a retaliatory strike, but also minimizes the likelihood of the use of nuclear weapons as a result of a technical failure of the missile launch authorization system.

Considering all of the above, it is in the interests of the parties to formalize a new model of cooperation in the military-political sphere, a legally binding treaty covering all their nuclear and other weapons, including a transparent mechanism for controlling such weapons: At the suggestion of Russia, the arms control agreements should be extended to all entering to the «nuclear club» of the state.

Considering that solving the problem of «horizontal» proliferation by creating a favorable international climate for the voluntary abandonment of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction by «threshold» and «latent» countries requires significant political will, it is not surprising that more and more countries are advocating a counterproliferation strategy. First proposed by the administration of US President George W. Bush, it took shape as a doctrine of the preventive removal of weapons of mass destruction from potentially dangerous regimes. In fact, we are talking about the forced disarmament of states that seek to gain access to nuclear, chemical and biological technologies. Counterproliferation has turned into a wide range of measures, including military action, diplomatic coercion to abandon nuclear programs, and control over suppliers of fissile materials, and the fight against the black market of military technology and materials. In essence, we are talking about a fundamental change in the approach to a number of basic provisions of the nuclear non-proliferation regime. According to the prevailing conviction in the United States - and the administration of the current President Donald Trump has not abandoned this postulate - there is a need to reinforce the nuclear nonproliferation regime with offensive elements aimed at actively countering the proliferation of fissile materials and nuclear technologies based on preventive action. This is the main difference between the counterproliferation strategy and the previous» defensive approach to the nuclear nonproliferation regime.

Another of the key aspects of achieving the world level of effective disarmament is precisely control over the policy called Global Zero.

Global Zero is a term used in disarmament and arms control literature to mean the destruction of weapons systems on a global scale, especially all or certain types of nuclear weapons. Thus, in the course of negotiations on the conclusion of the INF Treaty, Russia and the United States agreed to a global zero option with regard to carriers of short and medium-range nuclear weapons, thereby putting an end to the production, testing and deployment of groundbased ballistic and cruise missiles in these countries. range, respectively, from 500 to 1000 km and from 1000 to 5500 km. This agreement was radically different from all others, which provided only restrictions on the use of the above media in Europe.

The origins of the idea of global zero in the meaning of the complete final and verifiable destruction of nuclear weapons on Earth can be attributed to the time of the creation of the first atomic bombs. Back in January 1946, the first session of the UN General Assembly was established. United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. The competence of this Commission included, along with a number of other issues, the preparation of a proposal regarding the exclusion from national weapons of atomic weapons and all other basic types of weapons suitable for mass destruction.

Throughout the entire period of the Cold War, a number of scientists and public figures rang out calls similar to the one recorded in the Russell-Einstein Manifesto of 1955: Due to the fact that nuclear weapons will certainly weapons threaten the existence of the human race, we insist that the governments of all countries understand and publicly declare that disputes between states cannot be resolved as a result of the outbreak of a world war. The Manifesto, as well as the Mainau Declaration (1955) (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 1955), led to the formation of an international initiative of scientists against nuclear war, which in 1957 was organized in the form of the Pugwash Conference on Science and International Relations, better known as the Pugwash Movement.

However, given the central role of nuclear arsenals in the concept of mutual nuclear deterrence on which the national security doctrines of the world's leading states rested - both formally and implicitly - the leaders of the latter were in no hurry to publicly speak out in support of the idea of a global nuclear zero.

Only in 1985, almost 40 years after the formation of the UN Commission on Atomic Energy, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and US President Ronald Reagan issued a joint statement in Geneva in which they declared that a nuclear war cannot be won, and conducting is unacceptable (Mason, 1996). Reagan himself considered nuclear weapons completely irrational, completely inhuman, useless for anything other than murder and potentially destructive to life on Earth and human civilization (Krieger, 2008).

Speaking at the UN General Assembly in 1988, Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi presented his plan of action aimed at the elimination of nuclear weapons, a war with the use of which, he said, means the end of life as we know it on planet Earth (Gandhi, 1988).

With the end of the Cold War, calls for a global zero began to be heard louder and louder, and not only from the world community. In 1996, General Lee Butler, the former commander of the US Strategic Offensive Force, said that he sees for the first time the prospect of recovery, a world free from the apocalyptic nuclear threat (Kothari, 2001). In 1998, a joint appeal was released by 63 former military personnel from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, which said: We are convinced that nuclear weapons must be removed from the South Asian region and, moreover, from around the globe.

At the turn of the century, the idea of complete nuclear disarmament gained popularity among politicians at the highest level. In 1999, Chinese President stated: There are no reasons that impede the comprehensive prohibition and complete elimination of nuclear weapons. To achieve this goal, nothing is required except political will. In 2001, Benazir Bhutto, former Prime Minister of Pakistan, said: We owe our children a debt: we must build a world free from the threat of total nuclear annihilation.

In December 2008, with the support of more than 100 world-renowned civilian, military and political figures, the Global Zero International Initiative was launched, the goal of which is the phased withdrawal from arsenals and the subsequent verifiable destruction of all nuclear stockpiles held by official and unrecognized members Nuclear club. More than 90 participants in the initiative signed an open letter to the presidents of the United States and Russia on the eve of their meeting in April 2009, in which they urged B. Obama and D. Medvedev to commit themselves to the destruction of nuclear weapons.

However, the group's plans go well beyond today, according to the timetable developed by the participants of the initiative, the ultimate goal of Global Zero should be achieved by 2030. The first phase of the four-stage plan begins with an agreement between the United States and Russia to reduce their nuclear arsenals to one thousand nuclear warheads each, and by 2019 these nuclear weapons should reduce their nuclear stockpile levels by half. At this second stage, all other nuclear states (including those that are unrecognized) agree to freeze and subsequently begin to reduce their nuclear weapons. At the third stage - 2019-2023 - it is planned to conclude a formal legally binding treaty on global zero, which will include a multilateral schedule for reducing nuclear stockpiles around the world to a minimum number (the so-called minimum containment level). At the final stage, which will take a period from 2024 to 2030, the nuclear disarmament process will be completed and the verification and verification system will come into operation (Table 1).

| Table 1 International Export Control Regimes | ||

| Export Control Regime Name | Year of Creation | Main Directions of Activity |

| Zangger Committee | 1971 | Definition of goods falling under the category of nuclear material and equipment or under the category of materials specially designed to handle the use or production of fissile materials. |

| Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) | 1975 | Coordination of the export of nuclear materials, dual-use goods and technologies and equipment included in the two lists published in the annex to the IAEA information circulars. |

| Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) | 1987 | Restricting the proliferation of missile technology, as well as goods and technologies used in the creation of missile weapons. |

| Wassenaar Arrangement | 1996 | Ensuring control over the export of goods and technologies, dual-use and conventional weapons. |

| Australian group* | 1985 | Ensuring control over the proliferation of chemical and bacteriological (biological) weapons. |

| *The Australian group, strictly speaking, does not belong to the international nuclear nonproliferation regime, as it deals with other types of WMD. Nevertheless, this multilateral export control regime successfully operates in an area closely related to nuclear proliferation control. | ||

Thus, the Global Zero initiative demonstrates the existence of a serious strategy for moving towards a nuclear-free world - without waiting for an indefinite moment when the invention of a new, more powerful weapon will turn nuclear weapons into an artifact, but within the next ten years, subject to the signing of a treaty on complete nuclear disarmament, even if ratification will take the same amount of time (Table 2).

| Table 2 Global Zero Phased Plan to Eliminate Nuclear Weapons Worldwide |

| • Phase 1 (2019-2022) |

| Russia and the U.S. agree to cut nuclear stockpiles to 650 deployed warheads with a cap of 450 reserve warheads each. • Nuclear-armed nations engage in direct talks to strengthen global stability, reduce nuclear risks, and set the stage further stockpile cuts. All nuclear-armed countries negotiate and sign a legally-binding No-First-Use Treaty, prohibiting the first use of nuclear weapons in a conflict. |

| • Phase 2 (2023–2025) |

| Russia and the U.S. agree to cut their stockpiles to 300 “off-alert» warheads each, and all other nuclear-armed nations agree to not exceed this new limit. • Nuclear-armed and nuclear-capable nations continue direct talks to further global stability, establish universal fuel cycle safeguards, strengthen monitoring and verification methods to ensure all parties stick to their end of the bargain and develop a framework for the Global Zero Accords. |

| • Phase 3 (2026–2028) |

| Nuclear-armed and nuclear-capable nations negotiate, sign and ratify the Global Zero Accords, a binding international treaty that removes all nuclear weapons from military service (whether active or reserve) by 2030, and requires the complete destruction of nuclear warheads by 2045. |

| • Phase 4 (2029–2030) |

| All remaining nuclear weapons are taken offline and permanently retired – warheads separated from their delivery vehicles and securely stored until dismantlement has been confirmed by international monitoring – and all civilian nuclear programs are placed under international monitoring. |

| • Phase 5 (2030– |

| All remaining nuclear weapons are dismantled, and all weapons-grade uranium and plutonium is diluted and converted for use in civilian energy programs by 2045. Buildings on decades of successful monitoring and verification programs, implementation of the Global Zero Accords are carefully overseen by international institutions and confirmed by constant surveillance and on-site, no-notice inspections – indefinitely. |

In December 2008, the University of Maryland International Policy Assessment Program published the results of a survey conducted with the support of the Global Zero initiative among a population of 21 states (all nuclear countries except the DPRK and 13 non-nuclear countries), totaling 62 % of the world population (Larsen & Klingenberger, 2001). The respondents were asked to express their views on the possibility of concluding a multilateral agreement that would oblige all countries possessing nuclear weapons to destroy them in accordance with a certain timetable, while other countries would commit themselves not to develop them. Also, under the terms of the survey, all states would have the right to monitor the implementation of the terms of the agreement.

According to the survey, the vast majority (62 to 93%) of the population from the countries participating in the study welcomed the possibility of concluding such an agreement. The only exception was Pakistan, where, with 46% of respondents positively disposed towards signing a treaty on the elimination of nuclear weapons, 41% of respondents rejected it. On average, 76% of the world population support the idea of such an agreement, of which 50% are strongly in favor (17% and 7%, respectively, voted against).

Thus, the history of the movement for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons goes back 75 years. During this time, it acquired significant scope and influence, but the strategic task of multilateral final nuclear disarmament was not achieved.

As you know, the joint initiative of George W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev to destroy all nuclear weapons of the two countries within ten years failed due to the refusal of the American president to limit the SDI program to laboratory tests, which the Soviet leader insisted on. At the same time, thanks to the unilateral commitments undertaken, Washington and Moscow have solved most of the problem of reducing their tactical nuclear weapons (Bolton, 2005).

The administration of US President Bill Clinton has taken a number of positive steps in the area of nuclear nonproliferation. Its main achievement in this area was the CTBT signed in 1996, which, nevertheless, as already mentioned, was denied ratification by the US Senate. At the same time, during the second term of Clinton's presidency, the United States began to conduct so-called sub-critical tests, which, although they are non-nuclear explosive experiments and do not violate the provisions of the CTBT, are used to verify the reliability and efficiency of the existing nuclear arsenal and even test new ones. samples of nuclear weapons, which is considered by non-nuclear states as insufficient adherence of the countries carrying out such tests to the ideals of the NPT. At the same time, the American side initiated negotiations with Russia to revise a number of provisions of the Soviet-American Treaty on the Limitation of Anti- Ballistic Missile Systems of 1972 (ABM Treaty), which did not fit into the US plans to create a national missile defense system: Moscow did not make concessions to Washington, and the US President B. Clinton decided to shift responsibility for the deployment of the missile defense system to the future president.In 2001, George W. Bush, having come to power in the United States, proposed to accelerate the development of missile defense systems and expand the program for creating a national missile defense. He called on Moscow to replace the ABM Treaty with a new «treaty framework» that officially allowed the creation of the above-mentioned anti-missile system. Not meeting the understanding of the Russian leadership, George W. Bush announced in December 2001 the US withdrawal from the ABM Treaty, and 6 months later, in June 2002, this process was completed.

The period during which George W. Bush was in power in the United States is traditionally considered unfavorable for the international nuclear nonproliferation regime, even despite the fact that in 2002 Washington and Moscow signed another agreement on the limitation of strategic nuclear weapons - the SOR Treaty, which entered into force 1 June 2003 The administration of President George W. Bush, in which the neoconservatives played key roles, was awarded such a negative assessment for the course of US domination in international affairs that it chose, proceeding from a purely unilateral position. As a result, Washington took a lot of actions that contributed to the aggravation of the IRNNW crisis. Thus, at the 2005 NPT CD, the US delegation refused to support the previously approved (at the 2000 NPT CD) program 13 Practical Steps to implement Article VI of the NPT, which largely provoked the failure of this Conference: And in general, the George W. Bush administration- Jr. did not hide her negative attitude to the dichotomy nuclear disarmament - nuclear non-proliferation: We must focus our efforts on nuclear non-proliferation, especially on violations of non-proliferation obligations, and we must not divert our attention from such violations to issues of nuclear disarmament, so just as there are no problems with disarmament (Gerson, 2009).

US President Barack Obama became the first American president in the post-Soviet period to officially put the problem of nuclear disarmament at the center of Washington's foreign and defense policy. At the same time, it is hardly worth expecting in the near future new major initiatives on the part of the current American administration to advance the goals of the «global zero». On the eve of the elections, the main efforts of this administration will focus on stabilizing the situation in Iraq and Afghanistan, and within the country - on normalizing the economic situation, which remains very difficult.

In addition to possible difficulties that originate in the circumstances of US domestic policy, the successful implementation of the Global Zero initiative is faced with much deeper and more intractable problems of the level of interstate relations and global politics.

First, there is a clear superiority of the United States over any of the other states in the field of conventional armed forces, which inevitably affects the military policies of countries such as Russia and China.

The current Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation attaches more importance to nuclear deterrence than a similar American document, also because the United States today has a huge advantage in general-purpose forces and is the only country that produces long-range highprecision conventional weapons. Therefore, nuclear weapons, especially non-strategic air and sea-based ones, play an important role in ensuring Russia's national security, which, it seems, will only grow in the future. Whereas in the United States, on the contrary, the stake in ensuring national security is placed on high-tech conventional weapons (the concept of Rapid Global Strike), and nuclear weapons are seen as insurance that can be required for strategic deterrence.

More and more American experts and politicians agree that the United States can confidently rely on its conventional capabilities to confront new challenges and threats to national security. Michael Gerson, a renowned American expert on the theory of nuclear deterrence and arms control, uses the term «nuclearization» of conventional US military power to adequately describe the changes in its role and tasks in the military-political planning of Washington (Perkovich, 2008). The reason for this transformation, it seems, is the fact that, in modern conditions, high-3 precision conventional weapons are more suitable to play the role of a reliable deterrent: unlike the «nuclear taboo», there are no political and moral restrictions on the use of such weapons against any aggressor in the course of any conflict.

Overwhelming superiority - the United States in general-purpose forces can have a significant negative impact not only on the implementation of the Global Zero initiative, but also on bilateral and multilateral negotiations on nuclear weapons, since Washington's intentions to seek further reductions in nuclear arsenals will only increase the sense of its own sides of Moscow, and in the future also of Beijing, which the build-up of American high-precision conventional combat systems clearly puts at a disadvantage.

A truly destabilizing factor is that the United States is capable of destroying strategic targets of its opponents using conventional long-range weapons without formally unleashing a nuclear conflict. And in order to protect themselves from a retaliatory nuclear missile strike in this situation, the Americans are creating a global missile defense system. Moreover, Washington is categorically opposed to its missile defense plans being limited by the framework of any international agreements. All this undermines strategic stability and, as a result, slows down the process of nuclear disarmament.

Secondly, any initiative on global nuclear disarmament will inevitably face the need to resolve conflicts between its participants, if only in order to bring them to the negotiating table. Nuclear weapons are a dangerous modern addition to the historical animosity and mutual distrust that feed on regional divisions. Official and unrecognized nuclear states will not be able to start a joint movement towards a world free of nuclear weapons unless conflicts such as the Israeli-Arab confrontation or the struggle for Kashmir are resolved to the mutual satisfaction of the parties, or, at least, are not reduced to a level allowing the beginning of a nuclear confrontation.

At the heart of such conflicts are unresolved issues of territorial sovereignty, declared an internal matter by those of the participants who see the status quo as a favorable outcome of the conflict. At the same time, the solution of these issues is absolutely necessary for the achievement of peace and stability - an indispensable condition for nuclear disarmament. The three key hot spots in this regard are the Middle East, South Asia and Northeast Asia.

As you know, one of the main centers of instability is associated with the problem of the disputed Palestinian lands. The Middle East region serves as a good illustration of the security dilemma in action. Israel, surrounded by hostile Arab states, feels an existential threat and is not inclined to abandon its nuclear arsenal, as its neighbors demand as a measure to build confidence and transparency in the region. This position of Israel is one of the main obstacles to the start of negotiations on declaring the Middle East a zone free of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction. Iran's nuclear ambitions have added a new dimension to the regional complex of problems: the opacity of the ultimate goals of Tehran's nuclear program only increases the anxiety of neighboring Arab states and pushes them towards joining the nuclear race rather than towards the goal of complete nuclear disarmament.

The long-standing unresolved issue of Kashmir between India and Pakistan, now nucleararmed neighboring states, is turning South Asia into another potential nuclear-tinged hot spot. The history of these two states, as already mentioned, has three armed conflicts, as a result of which anyone's sovereignty over the aforementioned disputed territory was never confirmed. The volatile and uncertain security environment in the region provides little cause for optimism, even though both countries have undertaken significant efforts in confidence-building measures since 2004.

The function of the Indian nuclear arsenal is to prevent the development of events in favor of Pakistan, while the latter claims that nuclear weapons serve as a means for it to compensate for India's huge dominance of general-purpose forces, which is the main problem in ensuring the national security of this country, given the geographic characteristics its territories and traditional tensions between neighbors. Even if all the problematic moments in relations between the two states are resolved to the satisfaction of Pakistan and India decides on nuclear disarmament, New Delhi will need to provide Islamabad with satisfactory security guarantees in order to induce the latter to abandon its nuclear arsenal in the context of asymmetry in the field of conventional weapons. India itself will need similar security guarantees from China.

The third region potentially threatening the prospect of implementing the Global Zero initiative is the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia as a whole. The DPRK's acquisition of nuclear status and its numerous missile tests cannot but worry its immediate neighbors, South Korea and Japan. Both of these countries are subject to United States positive nuclear safeguards. And at the same time, South Korea and Japan, as well as Taiwan, whose status is another problem for the region, have an industrial base and technological knowledge sufficient to create their own nuclear weapons in a relatively short time. This already complicated equation needs to include China, whose economic and military power worries Japan. Any discussion of general nuclear disarmament is likely to cast doubt on the credibility of the expanded nuclear deterrence provided by the United States, and could in turn provoke a nuclear race in the region as the current North Korean nuclear issue remains unresolved. The sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council and international efforts to resolve this problem by negotiation have not yet led to a sustainable result. At the moment, when the attention of the world community is directed to the Iranian nuclear program, the issue of the DPRK's return to the ranks of the NPT parties seems to be on the back burner.

There is a significant interconnection between the dynamics of the development of regional relations in the global order and the prospects for progress towards the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons. In the opinion of the influential American experts in the field of nonproliferation of nuclear weapons, J. Perkovich and J. Acton, the United States is the connecting link here. They are already present directly or indirectly in each of the above equations of regional security and will play an even greater role in changing the balance of risks and threats, which must be achieved in order to convince regional actors with nuclear weapons to join the «nuclear five» in the cause of universal nuclear disarmament. Washington must compensate for the buildup of power by Beijing in Tokyo's strategic calculations. In turn, Russia and China are interested in obtaining certain guarantees in connection with the superiority of the United States in the general-purpose forces and in the space sphere, which the White House is unlikely to agree to give easily. In the Middle East, the military might of the United States, at least in part, influences the policies of Iran, Syria and other countries key to Israel's national security. Washington also provides military guarantees in the conventional sphere to Egypt, Jordan and the countries of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Persian Gulf. In South Asia, the strategic partnership between the United States and India, underpinned by the 2008 Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, but which also includes joint projects on conventional weapons, gives cause for concern to both Pakistan and China.

Thirdly, the current trend of the revival of interest in civilian nuclear energy in various countries of the world, called the «nuclear renaissance», despite its peaceful nature, is capable of creating a number of problems for global nuclear disarmament. Mastering the technology of the nuclear fuel cycle opens up the potential for the accumulation of weapons-grade fissile materials in quantities sufficient to initiate a military program. It is not surprising that such a prospect only strengthens mutual mistrust and suspicion between states in problem regions.

According to the World Nuclear Association, 30 newcomer countries have already expressed their intention to develop peaceful nuclear power programs in order to reduce the amount of harmful emissions into the atmosphere and compensate for the rise in hydrocarbon prices on the world market. 40 nuclear reactors are under construction at the moment, more than 130 are planned to be built by 2030, and more than 200 in the next period. This, in turn, raises concerns that the “horizontal» spread of materials and nuclear fuel cycle know-how will increase the risk of sensitive nuclear technologies falling into the wrong hands.

There are three main factors that determine the risk of nuclear proliferation in connection with the global “nuclear renaissance». The first is whether new nuclear reactors will be built in states with existing nuclear programs or in newcomer countries. There is nothing to worry about in this regard, only 5% of the aforementioned planned reactors are planned for construction in countries without nuclear technology. The second factor is the geostrategic context. Today, the countries that first start developing in the field of nuclear power are concentrated in zones of various levels of political instability - in Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. The Middle East region is a cause for justified concern, especially given Israel's unrecognized nuclear status and Iran's nuclear ambitions and their destabilizing influence on neighboring countries. Finally, the third factor is the nature of the nuclear technology used. The main concern in this regard is the proliferation of sensitive nuclear technologies, including the enrichment and processing of fissile materials. The transfer of such technologies significantly increases the risk of nuclear proliferation due to the possibility of fissile material falling into the wrong hands if nuclear facilities are not adequately guarded. While some countries (Bahrain, Vietnam, Indonesia and the UAE) have pledged not to use sensitive nuclear technology, others (Jordan) have not. The situation is further complicated by the fact that newcomer countries strongly reject the idea of restrictive obligations, which could become a legal obstacle to the possession of technologies for the enrichment and processing of fissile materials in the future. They believe that such commitments will only exacerbate the already existing inequality between nuclear and nonnuclear countries. In turn, this rejection of self-restraint undermines the confidence of other participants in international relations in the nuclear non-proliferation regime, including the countries with nuclear weapons, which does little to achieve the goals of general nuclear disarmament.

Fourth, there are problems that the Global Zero Initiative will have to face in its final stages, but the lack of approaches to solving which today can significantly slow down its implementation. Thus, without reliable verification mechanisms, it is difficult to imagine that nuclear states would agree to disarmament. Verification is a step-by-step process that helps build trust between partners and thereby enhances political resolve to move further towards the destruction of nuclear arsenals. Conversely, a weak verification mechanism creates doubts and increases the reluctance of parties to take risks. It seems that the approach to this issue of nuclear and non-nuclear countries will differ if the latter, perhaps, will not demand an over-strict system of checks, the former will not be satisfied with anything other than a regime as close as possible to the ideal, since for them we are talking about abandoning one of the the main elements of ensuring national security.

Technically, the verification procedure is a complex, lengthy and expensive process that requires engineering solutions that have not yet been developed. Controlling the dismantling of warheads, their delivery vehicles and production chain facilities presents a serious technical challenge, especially in an environment of lack of transparency and trust. The agreement on the architecture of the verification measures will be central to any negotiations on the implementation of the Global Zero initiative.

Another problem will be the creation of a system of coercion and punishment - after all, even in an ideal verification regime, it is impossible to exclude the possibility that some of the participants in the Global Zero initiative will try to circumvent restrictions. One of the difficulties on the way of the formation of such a system may be its subjectivity, taking into account that today there are numerous conflicting interpretations of what should be considered a violation of the nuclear non-proliferation regime. The researcher of the problems of the prohibition of nuclear weapons, professor of political science Bruce Larkin identifies at least six potential types of sources of disagreement (which, in turn, are divided into more specific subtypes) from disagreement about the fact of committing an intention to commit a violation to the use of certain instruments of coercion in the interests of individual countries (Larkin, 2008).

Finally, even in a situation of complete destruction of all nuclear arsenals, the concept of a recoverable potential should not be disregarded as unnecessary. Former nuclear states will certainly want to preserve for some time - at least for the entire transition period to «global nuclear zero» - the experienced knowledge and technologies for the production of nuclear weapons, so that in the event of an emergency threat to national security, they will be able to use the previous experience. Solving the problem of preserving the return potential in the form of human resources and knowledge will form an integral part of the architecture of the «postnuclear » regime discussed above. Moreover, this solution must be comprehensive, otherwise even one country with any noticeable advantage is likely to provoke a new race, characteristic of how quickly a state can restore its nuclear potential.

Thus, there are a number of both subjective - considerations of national security and lack of trust among international actors, and objective - mainly technical and legal - obstacles to the implementation of the goals of the Global Zero initiative.

However, there are other, less radical options for moving towards a world free from the threats associated with the existence of weapons of mass destruction. In this regard, the terms destruction, disarmament and prohibition should be distinguished as alternatives.

The Global Zero initiative, as mentioned above, aims at the complete, permanent and universal elimination of nuclear weapons. This is a maximalist approach that, although divided into stages, does not make any compromises in achieving the ultimate goal. According to Wolfgang Panofsky, a renowned physicist and advocate of nuclear disarmament, destruction means that there will be no nuclear weapons left in the world. And this seems to be truly utopian (Panofsky, 2007). Prohibition, on the other hand, looks like a perfectly achievable goal. The prohibition of the use of nuclear weapons does not imply their disappearance from the face of the earth. Skeptics rightly point out that the knowledge and skills of nuclear weapons production technology have become widespread and the physical destruction of their stocks is unable to prevent proliferation either in a horizontal or vertical form. There is, however, a historical precedent when the world community really managed to prohibit the production, stockpiling and use of other types of WMD - biological and chemical weapons through the conclusion of relevant international agreements. The regime created on the basis of agreements is not guaranteed against violations, and the process of its implementation is proceeding at a slow pace. However, it is generally recognized that he makes a significant contribution to strengthening international security (Perkovich, 2009).

The first proposal to ban the use of nuclear weapons came from the Soviet delegation, which, at the second meeting of the UN Atomic Energy Commission in June 1946, introduced a draft convention on the prohibition of atomic weapons, which provided for the prohibition of the production and use of atomic weapons, as well as three months for all stocks of finished and unfinished products of atomic weapons. However, this document was not adopted, since the UN Atomic Energy Commission could not reach a consensus and in July 1949 it ceased its work altogether. In May 1955, as part of the work of the UN deliberative Commission on Disarmament, the Soviet Union came up with a repeated proposal to ban atomic, hydrogen and other WMD, which was supported by a joint memorandum between Great Britain and France (with the participation of the United States and Canada), providing for a complete ban on nuclear weapons and withdrawal from arsenals. However, in August of the same year, Western countries withdrew their support for the Soviet initiative.

In 1961, the UN General Assembly adopted the so-called Ethiopian Resolution (1653 XVI), which declared that any state using nuclear or thermonuclear weapons should be considered as violating the Charter of the United Nations, acting contrary to the laws of humanity and committing a crime against humanity and civilization. However, subsequent efforts on the basis of the adopted resolution to convene a conference for the elaboration and signing of a corresponding convention were ineffective.

In 1972, the UN General Assembly approved another resolution submitted by the Soviet Union, which said «the refusal to use force or the threat of its use in all its forms and manifestations in international relations and the prohibition of the use of nuclear weapons forever». 73 countries voted for the resolution, with 4 against and 46 abstentions, including the USA, Great Britain and France. They stated that linking the non-use of force clause to the prohibition on the use of nuclear weapons significantly weakened the effectiveness of the said prohibition. Similar attempts were made repeatedly and later by individual countries (for example, India in 1982) and groups of countries until recently. Thus, at the 50th session of the UN General Assembly in December 1995, at the suggestion of 46 countries participating in the Non-Aligned Movement and other non-nuclear-weapon states that joined them, Resolution 50/71 (E) was adopted, which was called the weapons and demanding that the Conference on Disarmament begin negotiations on this issue in 1997, which, however, was not carried out.

In theory, the prohibition of the use of nuclear weapons can follow one of the two paths proposed by the US National Academy of Sciences, within the framework of a multilateral negotiation process, or through an agreement between the countries possessing nuclear weapons, both official and unofficial. Another option seems to be amending the NPT accordingly, which, however, may prove to be much more difficult to implement and leave countries that are not parties to the treaty out of the process.

Conclusion

Radical approaches to problems in the nuclear sphere, like abandoning arms control or the nuclear nonproliferation regime itself, must be opposed by a balanced course of restoring diplomatic negotiations as the main instrument for resolving differences, export control, physical protection of objects and materials, international guarantees, control and data analysis, finally, respect for legally binding agreements. It is thanks to this course that the gloomy predictions of past years have never materialized. The main merit in this belongs to Russian-American cooperation in the field of limiting and reducing nuclear weapons, the almost universal nature of the NPT and cooperation within the IAEA, the expansion of zones free of nuclear weapons, and the adoption of strict export restrictions - that is, everything that makes up the system of the non proliferation regime nuclear weapons. The efforts of the world community to strengthen it, although they were not equally effective, worked to maintain the security of individual countries and international relations in general.

A real and consistent path to complete nuclear disarmament is extremely difficult and fraught with considerable dangers to strategic stability, requires the highest realism and professionalism, taking into account all the subtleties and interrelationships of the political, military, economic and technical aspects of the problem. A thorough and well-grounded coordination of all elements of the process, it’s bilateral and multilateral formats, a clear pairing of steps in disarmament and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, in measures of a treaty-legal, military-technical nature, and even in coercive actions is necessary. All these measures must be carried out simultaneously with the implementation of the most difficult task - the restructuring of the entire traditional system of international security-so that nuclear disarmament does not remove the taboo on large-scale (world) wars using conventional weapons, other types of WMD and systems based on new physical principles. That is, it is necessary not only to comprehensively address the problems facing individual elements of the nuclear nonproliferation regime, but also to consciously include the latter in the broader context of international security.

There is no reliable and simple means against the danger of nuclear proliferation. No country alone can solve this problem. That is why the improvement of control over the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons in modern conditions is one of the most important areas of the international community's activities, ensuring the stability of interstate relations.

Deepening international cooperation within the framework of multilateral nonproliferation regimes presupposes closer interaction between government agencies and services of partner countries. And although Russia's relations with some partners (including the United States) are complex and contradictory, it is clear that cooperation in countering the proliferation of nuclear weapons is the area where the long-term interests of various states coincide to the greatest extent.

References

Bobrov, R. L., Malinin, S. A., & Bogdanov, O. V. (1964). General and complete disarmament? International E legal questions. E publishing house International relations.

Chekov A.D. (2013). Nuclear disarmament and global security in the 21st century. MGIMO University Bulletin. Issue, 1(28), 292-321.

Derigizalova, L.V. (2005). Problems of ensuring international security after the end of the Cold War. Tomsk State University Bulletin, 288(4), 58-67.

Gandhi, К.A. (1988). World free of nuclear weapons. Address to the third special session on disarmament of the U.N. General assembly in New York. Statements on foreign policy. New Delhi: Ministry of External Affairs.

Gerson, М (2009). Conventional deterrence in the second nuclear age. Parameters, 39(3), 33-40.

Kothari, S., & Mian, Z. (2001). Out of the nuclear shadow. London: Zed Books.

Krieger, D. (2008). Ronald Reagan: A nuclear abolitionist. Nuclear age peace foundation. Retrieved from http://www.wagingpeace.org/articles/2008/01/13_krieger_reagan_abolitionist.php7krieger

Larsen, J.A., & Klingenberger, K.J. (2001). Controlling non-strategic nuclear weapons: Obstacles and opportunities. USAF/INSS.

Madsen, C. (2015). German disarmament after World War I: The diplomacy of international arms inspection 1920-1931. European Legacy-Toward New Paradigms, 20(8), 858-859.

Mason, J. (1996). The cold war, 1945-1991. New York: Routledge.

Panofsky, W.K.H. (2007). A nuclear-weapon-free world: Prohibition vs elimination. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved fromhttp://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/op-eds/nuclear-weapon-free-world-prohibition-versuselimination

Perkovich, G. (2008). Acton J. abolishing nuclear weapons. London: IISS.