Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 5

Media & the Under-Reporting of Faulty Implementation of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005: A Case Study of the State of West Bengal

Jayita Moulick, Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology University

Tulishree Pradhan, Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology University

Pradip Kumar Sarkar, Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology University

Nilanjan Chakraborty, Amity University

Citation Information: Moulick, J., Pradhan, T., Sarkar, P.K., & Chakraborty, N. (2022). Media & the under-reporting of faulty implementation of the protection of women from domestic violence act, 2005: A case study of the state of West Bengal. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(5), 1-12.

Abstract

Marital violence pervades all cultures across all times and was normalized as a right of the husband as a way of chastising the wife for failure to perform her wifely functions. The issue of marital violence is complex as it is often perplexing for many to understand the reason behind the battered women staying back in her abusive marital relationship, this phenomenon of domestic abuse is the most controversial as the right of the State to interfere into the privacy of the marriage is often cited as infringement, and this abuse is also the most under reported as has often been seen in all societies, the burden of protecting the family honour befalls the women and she has been taught to ‘not to wash her dirty linen in public.’ The object of this paper is to reveal of the faulty implementation of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, pertaining to the State of West Bengal. This empirical study will show how the provisions relating to the Service Providers have largely remained unimplemented and how this in turn is affecting the Protection Officers in discharging their duties.

Keywords

Marital Violence, Domestic Abuse, Privacy of Marriage, Patriarchy, PWDV Act

Introduction

Since prehistoric times, women were under the bondage of man due to her physical vulnerability. Women were taught from an early age that her only goal in life was to get married, bear children; show obedience to her husband at all times and is no more than a slave with the nomenclature of a wife (Mill, 2018).

Marital violence occurs between a superior and inferior relationship that husbands and wives share in their home. This hierarchical framework revolves around the authoritative husband and his set of rules which are to be followed by the wife in the process of rendering her service to the master-husband and when this patriarchal structure breaks down, marital violence is inevitable (Denzin, 1984). A society which assigns a subordinate status to its women, a society where the husband enjoys a dominant position being the rule maker and its enforcer at home, the presence of domestic violence should not come as a shock to such a society (Chapman, 1990).

Interestingly, with the evolvement of our societies, the phenomenon of domestic violence is becoming more complex and gruesome; in spite of the emergence of laws protecting women, women friendly investigation procedures, the supposed high media coverage of such issues and community support for such battered victim women, are unable to cure this menace from the society (Agnew, 1997). In reality, a small number of cases are reported, the percentage of convection is even smaller, the victim ends up getting blamed and shamed by the society and the abuse continues. It appears that dealing with domestic abuse is the most complex procedure than with any other crime (Solanki, 2011).

The role of the media is paramount in helping to curb this menace. It has often been seen that the media hardly aids in spreading awareness regarding such issues of domestic violence or the problem of dowry (Agnes & Mello, 2015). It often ends up reporting cases where the perpetrator secures an acquittal rather than on focusing on those cases wherein conviction is secured, which proves to be counter-productive as it passes the message in the society that domestic abuse is a myth, some women conspire to harass their husbands and lodge false cases against them hence such high level of acquittals (Sachdeva, 2008). In the absence of social awareness regarding such issue, what the society fails to comprehend is that evidence in these cases is hardly available as what happens behind the closed doors of the bedroom is not known to all and that these issues regarding women and their dignity and safety, not only have an immediate effect on such women but also has a lasting effect on that society wherein such violence pervades without effective prevention (Brownridge, 2009).

It is imperative to understand the psyche of women specially such battered women to effectively deal with the phenomenon of domestic violence (Renzetti, 2011). The gender roles of our society weaves into the minds of women from a tender age that harassment, battering, sexual assault and the likes of such violence is a natural part of every woman’s life and it is the fault of the victim women to suffers the harm as she is but the harbinger of such fate; freedom from such abuse is but impossible and reporting such abuse is bringing much shame to herself and her family. It is with this attitude the society breeds our women folk, a feeling of self-doubt and selfblaming has become a common part of the psyche of almost every woman, in the face of such assault (Clarke, 1997). The perpetrators on the other hand, also victims of such gender role stereotyping, has been breed with the false sense of masculinity, which demands an attitude of aggression towards the opposite sex, such display of aggression being normal and acceptable forms of mechanism that society expects every man to aspire to be (Edi, 2010). Images of women gyrating their body on songs with lusty lyrics becomes popular, romanticising the harassment of women by the ‘hero’ of the movie and this attitude is admired by women, aspired by men and accepted by the society; pornography is hardly brought to books and mistreating the wife has become a popular feature in almost every daily soap especially in the south Asian cultures. A spate of multinational companies investing into electronic media and the hugely successful media houses regularly comes up with a host of programs popularising the idea of sexual violence, marital abuse, extra marital relationships and regularly uses women’s bodies from selling a car to a soap, turning women to nothing but sex objects, an object to be used and abused, not to be respected (Kishore & Johnson, 2006). This practice adversely plays into the vulnerable minds of millions of young boys and men who learn to fantasise for instant gratification especially sexual gratification and also learn not to even bat an eye while mistreating women to get what they need from such women (Straus & Gelles, 2017). What we are failing to grasp is that this culture is turning one sex against another, one becoming the hunter another hunted. The level of harassment, eve teasing kidnappings rapes murders and domestic abuse is but a standing proof of the ill effects of such media practices (Waghamode, 2013). Again, the adverse effect of such practices is hardly being realized by the society especially in the absence of any kind of awareness programs on such socially relevant women’s issues done by the media, it would be safe to say that media underplaying its responsibilities towards such issues and hugely propagating the abuse of women issues by bringing such negative programs to every household every day, aiding to drill into the minds of the society that fact that women must yield to men, it is but acceptable to abuse women and cultivating the urge to desire a particular type of women; young, beautiful, dutiful and submissive (Dhar, 2007).

Efforts Taken By the International Legal Instruments

The United Nations since 1975 have through a plethora of conventions, shed light on the phenomenon of domestic violence, before the international forum. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights exhorts that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (ART. 1, UDHR). Equality being the foundation of all our fundamental rights, marital violence violates this very equality as it is perpetrated against women, a clear discrimination on the basis of her sex as domestic violence against her enforces her subordination in the society (French et al., 1998).

The Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women, 1979, the World Conferences on Women both in 1980 & 1985, the UN Resolutions of 1985 and 1990, the General Recommendation No. 19 of 1992, the Declaration of the Elimination of Violence against Women, 1993, the Vienna Accord of 1994 and the Beijing Declaration and the Platform for Action of 1995, recognised this fact and urged State Parties to intervene in both the public and the private life of its citizens through appropriate measures including legislations, to prohibit offences against women. It was due to this international impetus that the Indian Parliament brought in The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. Although, domestic violence was recognised as a criminal offence in our country from 1983 when Section 498A was inserted in the Indian Penal Code, 1860, owing to the commendations of both the 237th and 243rd Law Commission Reports, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, came into force which not only had a wide scope to protect women from domestic abuse but also provides a wide array of remedies to serve the various requirements of the victims.

The PWDVA, 2005, has several unique features and the appointment of Protection Officers and Service Providers are paramount among them. The Protection Officer is an appointed officer under the State Government to act as a facilitator of the Act and a direct link between the Magistrate and the victim. The Service Provider is a voluntary association with a cause of protecting the rights and interests of women, registered under the State Government to assist the victims by securing for them various welfare provisions as provided by the Act. Both these posts have been granted huge powers that include recording the domestic incident report coordinate with the concerned police stations and provide medical care and shelter facilities. As the Protection Officers and the Service Providers act as enforcement mechanisms under the Act, they are interdependent on each other for the best execution of their duties under the Act. Yet when the ground realities do not match the grand scheme of this reformist piece of legislation, it is the victims who fail to reap the benefit of this propitious enactment.

Presently, the war against violence against women has amplified, there is relatively better attention from the media over discussions and debates over such abuses and activists and advocacy groups too are coming up with programs to spear awareness regarding such issues pertaining to the welfare of women yet all such efforts are falling short and the phenomenon of violence against women is spreading like an epidemic. Again, the violence against marginalized Dalit, Adivasi and women in conflict zones hardly gets the attention which they desire.

Data Analysis

An empirical study was conducted as mentioned above, to understand the implementation realities of The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, in the State of West Bengal. The following Tables i.e., Tables 1 to 4 contains the questions that have been asked to the Protection Officers who have been appointed under Sec. 8 of the Act, one per district, by the State Government. The questions are mostly regarding the Service Providers who were supposed to be appointed under Sec. 10 of the Act, 2005, but when the researcher was conducting the field work in the above mentioned six districts, she could not find a single Service Provider working in those districts. The role of the Service Provider is paramount for not only the implementation of the Act, 2005, but also for giving the muchneeded support services to the victims of marital abuse. It is for this reason, as per Sec. 10 of the Act, 2005, any registered voluntary association working for the cause of women, may register with the State Government as a Service Provider under the PWDV Act, 2005. The duties of the Protection Officer and that of the Service Provider are complementary to each other and in the absence of one office, both, the office of the other and the intention of the PWDV Act, 2005, suffer in unimaginable proportions.

| Table 1 The Selection of the Districts for Empirica Research has been done Accordingly: District Wise Literacy Rate | ||||||

| Year-2001 | Year-2011 | Percentage (%) | ||||

| Sl. No. | Districts | LitI | LitII | Lit perI | Lit perII | Increase(>) |

| 1. | West Medinipur | 3037107 | 3969751 | 80.17 | 87.67 | 7.60 |

| 2. | State Capital Kolkata | 3382104 | 3648211 | 80.87 | 87.15 | 6.29 |

| 3. | Uttar Twenty-four Parganaas | 6151528 | 7798723 | 78.08 | 84.96 | 6.89 |

| 4. | Haorah | 2895626 | 3642618 | 77.02 | 83.86 | 6.85 |

| 5. | Hhugli | 3333989 | 4140488 | 75.12 | 82.56 | 7.45 |

| 6. | Daarjeeling | 1008289 | 1328219 | 71.80 | 79.93 | 8.14 |

| 7. | East Medinipur | 3127211 | 4173523 | 70.42 | 79.05 | 8.64 |

| 8. | Dakhina Twenty-four Parganaas | 4067344 | 5639113 | 69.46 | 78.58 | 9.13 |

| 9. | Bardhhamaan | 4205147 | 5350198 | 70.19 | 77.16 | 6.98 |

| 10. | Naadia | 2644462 | 3524074 | 66.15 | 75.59 | 9.45 |

| 11. | Kaoch Bihaar | 1386966 | 1879985 | 66.4 | 75.50 | 9.20 |

| 12. | Dakshin Dinajpur | 799480 | 1102356 | 63.59 | 73.87 | 10.30 |

| 13. | Jaalpaiguri | 1810084 | 2527019 | 62.86 | 73.80 | 10.97 |

| 14. | Baankura | 1734223 | 2264014 | 63.45 | 70.96 | 7.56 |

| 15. | Beerbhum | 1553853 | 2175924 | 61.49 | 70.90 | 9.44 |

| 16. | Murshidaabad | 2620539 | 4134585 | 54.36 | 67.54 | 13.20 |

| 17. | Puruliyaa | 1182285 | 1656941 | 55.58 | 65.39 | 9.83 |

| 18. | Maaldah | 1332705 | 2136899 | 50.29 | 62.72 | 12.45 |

| 19 | Uttar Dinajpur | 923478 | 1521934 | 47.89 | 60.13 | 12.26 |

| Table 2 Average Database of 2011 Census | ||

| Sl. No. | District | Lit (2011) |

| 1 | South Dinaajpur | 01102355.00 |

| 2 | Daarjeeling | 01328218.00 |

| 3 | North Dinajpur | 01521933.00 |

| 4 | Purliya | 01656940.00 |

| 5 | Koach Bihaar | 01879984.00 |

| 6 | Maldaah | 02136898.00 |

| 7 | Beerbhum | 02175923.00 |

| 8 | Baankura | 02264013.00 |

| 9 | Jalpaaiguri | 02527018.00 |

| 10 | Naadia | 03524073.00 |

| 11 | Haorah | 03642617.00 |

| 12 | State Capital Kolkata | 03648210.00 |

| 13 | East Medinipur | 03969750.00 |

| 14 | Murshidabaad | 04134584.00 |

| 15 | Huguli | 04140487.00 |

| 16 | West Medinipur | 04173522.00 |

| 17 | Bardhamaan | 05350197.00 |

| 18 | Dakhina Twenty four Parganaas | 05639112.00 |

| 19 | Uttara Twenty four Parganaas | 07798722.00 |

| Table 3 Standard Deviation and the Data | ||

| S No | District | Lit (2011) |

| 1 | South Dinajpura | 1102356 |

| 2 | Daarjeeling | 1328219 |

| 3 | North Dinajpura | 1521934 |

| 4 | Purliya | 1656941 |

| 5 | Koach Bihaar | 1879985 |

| 6 | Maldaah | 2136899 |

| 7 | Beerbhum | 2175924 |

| 8 | Baankura | 2264014 |

| 9 | Jaalpaiguri | 2527019 |

| 10 | Naadia | 3524074 |

| 11 | Haorah | 3642618 |

| 12 | State Capital Kolkata | 3648211 |

| 13 | East Medinipur | 3969756 |

| 14 | Murshidabaad | 4134584 |

| 15 | Huguli | 4140487 |

| 16 | West Medinipur | 4173522 |

| 17 | Bardhamaan | 5350197 |

| 18 | Dakhina Twenty four Parganaas | 5639112 |

| 19 | Uttara Twenty four Parganaas | 7798722 |

| Table 4 Showing Demography of Districts | ||

| Sl. No. | District | Demography |

| 1 | North Dinajpura | 1521934 |

| 2 | Beerbhum | 2175924 |

| 3 | Naadia | 3524074 |

| 4 | East-Medinipur | 3969751 |

| 5 | West-Medinipur | 4173523 |

| 6 | Burdawan | 5350198 |

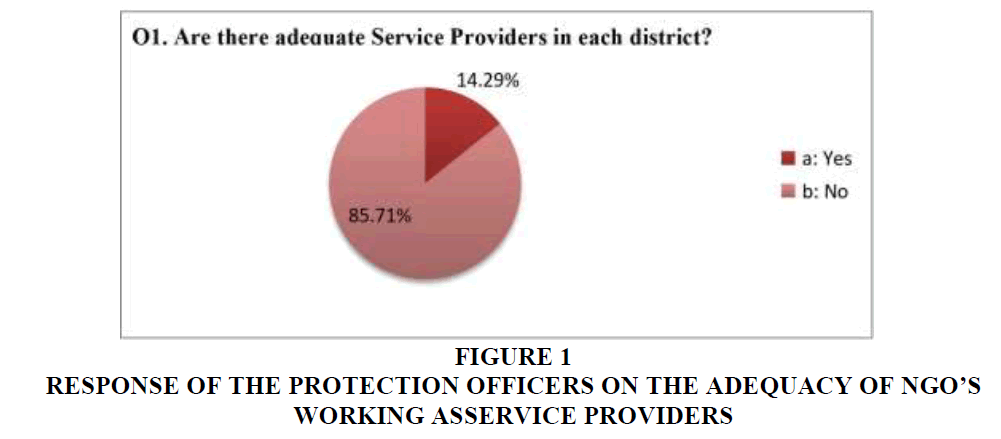

On the question being asked to the Protection Officers regarding the adequacy of Service Providers working in the districts, the Figure 1 shows a dismal picture as only around 14% of Protection Officers answered in the affirmative, clearly showing that the provisions of the Act regarding registration of Service Providers have not been complied with in the State of West Bengal.

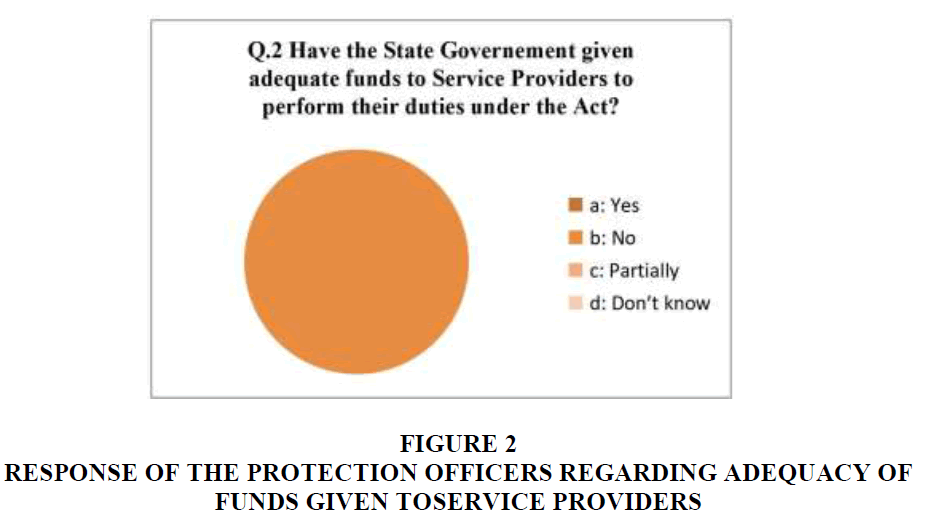

The Protection Officers were further asked about the adequacy of funds allotted to the Service Providers by the State Government and the answer let to further disappointment as all of the officers unanimously answered in the negative (Figure 2). It is due to lack of funds that either NGOs become reluctant to register as Service Providers under the Act, or after registration they find it difficult to continue as such and as a consequence, they either deregister or become indifferent to their duties towards both the victims and the law. This Figure 2 clearly indicates the lackadaisical attitude of the government towards implementation of this piece of legislation.

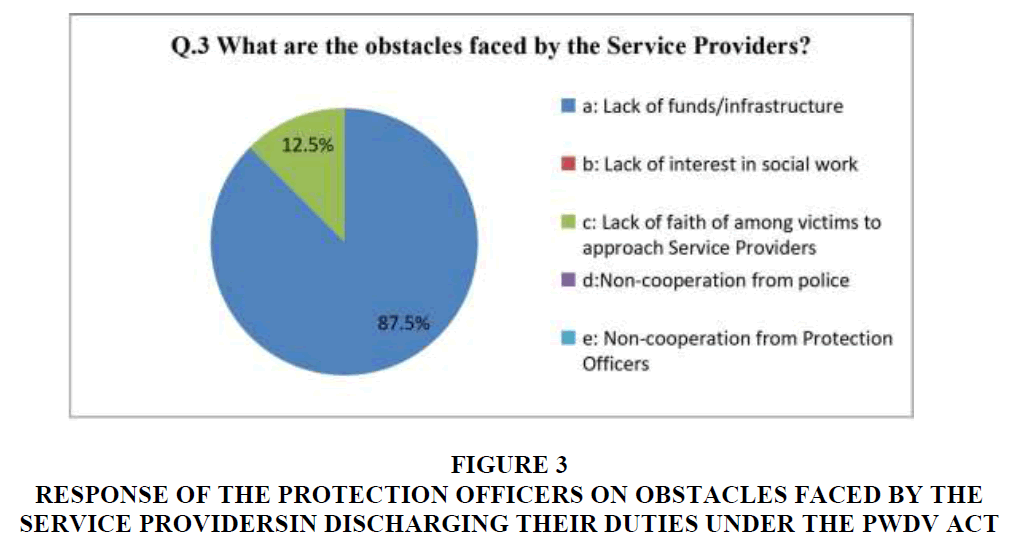

Similarly, when the Protection Officers were asked about the various obstacles faced by the Service Providers in rendering their duties under the Act, around 87% recognized lack of funds and infrastructure to be the primary cause (Figure 3). Another obstacle that emerges is relating to the lack of faith among the victims to approach the Service Providers; this is a logical correlate of both the above figures as a half-hearted service from Service Providers will seldom result in building any kind of confidence among these victim women towards the office of the former. Victims of domestic violence needs a lot of care and compassion and when they are met with either an absentee Service Provider or a lethargic one, they naturally feel reluctant to approach or trust the office a second time.

Figure 3 Response of the Protection Officers on Obstacles Faced by the Service Providers in Discharging their Duties Under the PWDV ACT

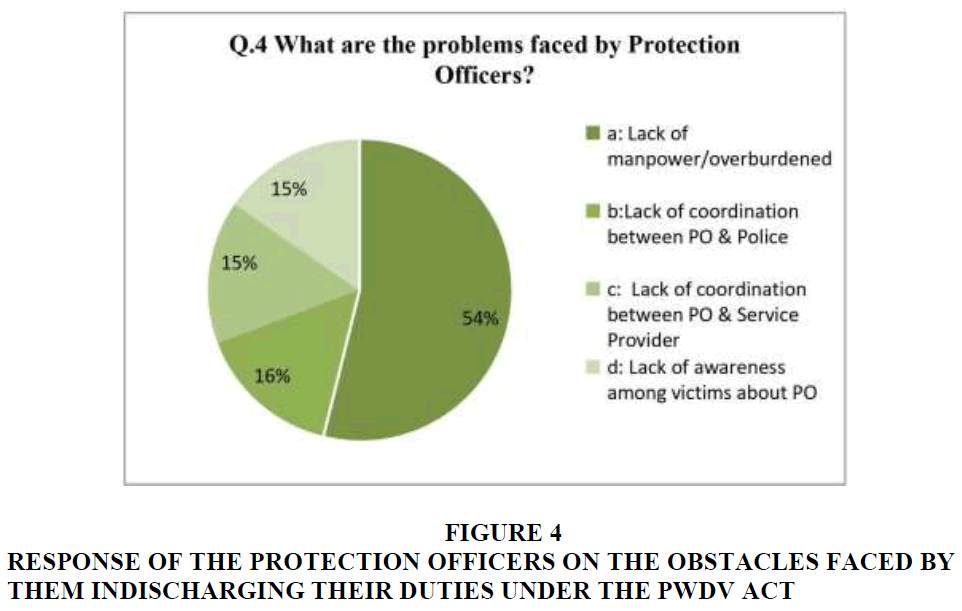

When the Protection Officers were asked about the various obstacles, they face which prevents them from executing their duties under the Act; a majority of them recognized shortage of man power and being over-burdened as primary impediments, other minor obstacles also being the absence of team work between Protection Officers and the Service Providers or the police (Figure 4). The office of the Protection Officer and the Service Provider are complimentary to each other and they are also given similar powers under the Act for the utmost assistance of the victims, yet if one office becomes undependable, the other has to shoulder the responsibilities of the Act, alone, resulting in inferior execution of service to the victims.

Figure 4 Response of the Protection Officers on the Obstacles Faced by Them in Discharging their Duties Under the PWDV ACT

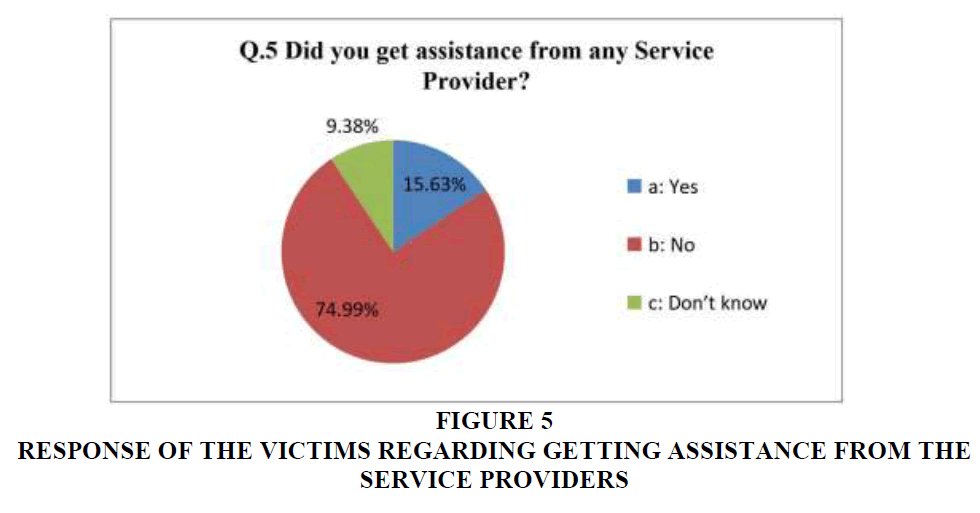

Lastly, when the victims were asked whether they received any kind of assistance from the Service Providers, around 75% responded in the negative and around 9% were not even aware of the existence of any office of Service Providers in their district (Figure 5).

Methodology

This study is based on empirical research combined with analytical method. Qualitative method: In analytical method, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, has been critically analysed.

Quantitative Method of Sample Selection

Quantitative Data Collection-The data required for the study has been collected through structured questionnaire. The questionnaires had appropriate scaling technique to measure the answer. The aim of the questionnaire was to assess the Attitude, Knowledge and Practice of the targeted samples. The said measuring was done by application of tools of data analysis like SPSS and Regression.

Researchers have followed the data of 2011 year census. Though after those four more districts have been created in West Bengal, but as the researchers used the last census data and that is why the Table 1 contains 19 districts only.

First Standard Deviation (herein after SD) of the table has been calculated and then the average (herein after AV) of the literacy rate was taken. (Standard Deviation (SD): 1393201 & 1727210; Average: 2484022, 3295503, 66.5753 & 75.63947

After getting the average, the database of 2011 census (Table 2) literacy has been segregated in two categories.

1. Districts below the average, coloured with Dark green;

2. Districts above the average coloured with Light green.

In this stage the object was to have the heterogeneity of the data. Population was already included within literacy database. So, the researchers did not segregate the districts separately on the basis of population. Here the researchers have applied standard deviation and the data was stratified taking log ± € i.e., μ ± € and the researchers got four cluster of districts Table 3.

Next, these ten (10) districts were filtered applying demography and crime record. Applying those filters, the number of districts was finally reduced to six for the purpose of collection of data and the districts selected stands as follows (Table 4).

Data Collection

This paper is largely based on the research work of Ms. Jayita Moulick, for which a total of 187 samples were collected pertaining to Protection Officers, Judicial Magistrates, Police Officers, Lawyers and Victims, but for the purpose of this paper, only data relating to the Protection Officers and victims have been used, the sample size being 69 (Total Victims: 59; Total Protection Officer: 10)

Results and Findings

The position of the Service Provider is of paramount importance as apart from having similar duties with that of Protection Officers, the former is bestowed with some crucial duties which relate to cater to some basic yet vital needs of the victim when she approaches the law for protection from her abuser. The foremost among is to provide for shelter and medical care for the victim. Indeed, many women resist the temptation to report violence and seek justice in the fear of losing her shelter and thus continue to remain a prisoner in her abusive home. The progressive remedies provided by this Act, aims to take care of these basic needs and help such victim women to break the shackles of abuse and be emancipated. Yet, the non-compliance of these very provisions acts as a domino effect in keeping victims from benefiting from this Act and lead a better life.

India is considered to be the 4th dangerous country in the world for women to live in; the incidences of rapes, gang rapes, murders, kidnappings have increased manifolds over few years, although scholars say these government statistics is hugely under-reported. The promotion of gender equality in schools and colleges as part of the curriculum, media interventions to promote such programs and awareness campaigns is the first step towards breaking the shackles of gender roles stereotyping and achieving an equal society for both the genders. Legislations and law enforcement agencies, alone cannot counter the phenomenon of violence against women; community intervention through social awakening bringing in a change in the mind-set of especially the younger generation is the need of the hour. Visual media can play a huge role in bringing in this change as it has reached every household and every pocket in equal measures. It can bring in news showing the pitiable conditions of battered women facing domestic violence and the hapless state in which they are in due to the unavailability of the much-needed services that the legislature promised them by enacting The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. Questioning representatives of the government regarding their policies in popular debating platforms, sells; the same platforms can also be used to pint out the loopholes in the implementation of the Act, 2005, and such shall also sell! In doing so the media will not only end up in positively forcing the government to rectify the wrongs but will also create awareness about the phenomenon of marital abuse and the law. It is only through such responsible programs, the media will aid in ultimately giving women their due.

Conclusion

The paper only concentrates on the provisions relating to the conditions of work of the Service Provider and the Protection Officer, the two key implementing authorities of the PWDVA, 2005; one can hardly function without the support of the other. The phenomenon of domestic violence is widely prevalent in our country and to stem it out from the roots is but a utopian thought. It is interesting to note that in spite of the fact that the media is called the third eye of democracy, it has shown zero interest in reporting the real state of the situation regarding the implementation of the PWDV Act, 2005, or the lack of it to the public. Every day hundreds of articles are printed but one can’t seem to find a single article that shows the loopholes in the implementation of the Act, 2005. With an audience and readership over a million, if such news about faulty implementation of the Act in registering and retaining Service Providers in West Bengal and the consequent obstacles faced by the Protection Officers in discharging their duties under the Act and the impediments faced by the victims of domestic violence in getting the services they not only deserve but are mandated by the PWDV Act, were reported by the media, it is but logical that such would have resulted in creating pressure on the government to rectify the wrongs. But such did not happen; instead today’s media has become everything that it was not supposed to be. But the media can no longer shy away from its responsibilities of unbiased research, evaluation and reporting of issues regarding the ineffective way the PWDV Act is working in West Bengal as doing such is pertinent for protecting vulnerable women like those of victims of domestic abuse as it is the duty of a civil society to provide women a safe home atmosphere and do right by her. This law was passed to provide civil remedies to victim women and address this evil phenomenon through counselling and conciliation. But the legislators forgot to ensure for a strict implementation mechanism, as a result of which a law which could have been a beacon of hope, failed to meet the needs of the vulnerable victims as its provisions largely remained restricted to the pages of judgements and the statute.

Limitation of the Research

The study is a posterior analysis of the loopholes in the effective application of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, concentrating only on marital relationships under the Act, in relation to the State of West Bengal.

Acknowledgement

The author Jayita Moulick is a recipient of Indian Council of Social Science Research Doctoral Fellowship Contingency Grant for the Year 2018- 2019. This research paper is based on her doctoral work and the responsibility of the opinions that has been expressed belongs to the author and the authors.

References

Agnes, F., & Mello, A.U.D. (2015). Protection of women from domestic violence. Economic and Political Weekly, 50(4), 76-84.

Agnew, V. (1997). The west in feminist debate: Discourse and practice. Women’s Studies International Journal, 20(1), 3-19.

Brownridge, D.A. (2009). Violence against women: Vulnerable populations. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chapman, R. (1990). Violence against women as a violence of human rights. Social Justice, 555.

Renzetti, C.M. (2011). Sourcebook on violence against women. Los Angeles: Sage.

Clarke, A. (1997). Ending domestic violence: Changing public perceptions/halting the epidemic.

Denzin, N.K. (1984). Toward a phenomenology of domestic, family violence. American Journal of Sociology, 90(3), 483-513.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dhar, S. (2007). Domestic violence against women: A conceptual analysis. The Academy Law Review, 122.

Edi, L.R. (2010). The war against domestic violence. New York: CRC Press.

French, S.G., Teays, W., & Purdy, L. M. (1998). Violence against women: Philosophical perspectives. Cornell University Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kishor, S., & Johnson, K. (2006). Reproductive health and domestic violence: Are the poorest women uniquely disadvantaged? Demography, 43(2), 293-307.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mill, J.S. (2018). The subjection of women. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Waghamode, B.D. (2013). Domestic violence against women; An analysis. International Research Journal of Social Sciences, 68-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sachdeva, A. (2008). An exhaustive commentary on the protection of women from domestic violence act & rules. Jain Book Agency.

Solanki, G. (2011). Adjudication in religious family laws: Cultural accommodation, legal pluralism, and gender equality in India. Cambridge University Press.

Straus, M. A., & Gelles, R. J. (2017). Societal change and change in family violence from 1975 to 1985: As revealed by two national surveys. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56-59.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 14-May-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-12015; Editor assigned: 16-May-2022, PreQC No. JLERI-22-12015(PQ); Reviewed: 30-May-2022, QC No. JLERI-22-12015; Revised: 25-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-12015(R); Published: 01-Aug-2022