Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 4

Measuring Consumer Reactions During Product-harm Crisis Among Indian Consumers

Utkal Khandelwal, GLA University

Kushagra Kulshrestha, GLA University

Vikas Tripathi, GLA University

Keywords

Product Harm Crisis, Consumer Reaction, Purchase Intetion, Brand Equity.

Introduction

Building a strong brand is now a most significant achievement for any marketing firm. With a strong brand, companies can build a long and sustainable relationship with existing customers (Ambler, 1997). Maintaining a strong brand is not an easy task, there is huge risk always been associated with all your business actions especially in media oriented world. Thus, companies are managing good public relation with every stakeholder. But the media are also publicized any defects or negative aspects of the brand lead to tarnish your brand, destroyed public image and reputation (Davies et al., 2003) and also affect consumer purchase intention (Tsang, 2000; Laufer and Gillespie, 2004). This phenomenon of publicizing products is found defective or dangerous is known as product harm crisis (Dawar and Pillutla, 2000). And this is because of several reasons, such as product misuse, manufacturer’s negligence, or sabotage (Siomkos and Malliaris, 1992) and the result of this are more serious such as damage the company’s reputation, decreasing market share, costly product recalls and damage carefully nurtured brand equity (Kotzegger and Schlegelmilch, 2013; Van-Heerde et al., 2007).

In the recent past, we have heard about various product harm crises in India that have aggravated societal attention include Samsung Galaxy Note 7, where company had to recall more than three million devices it had sold, after the reports of overheating and exploding batteries, Honda India announced a recall of more than 1.9 lakh cars because of the faulty airbags, Maruti Suzuki also faced the recall of its two major brands, Baleno (75,419 units) and Dzire (1,961 units) due to upgrade the airbag controller software in the vehicles. Many times it happens after product recall brand trust decline. Potential long-term brand damage from the recall and production deferment of Samsung's Galaxy Note 7 phone are a greater menace to its brand equity than the financial impact (Economic Times, 2016).

Product harm crisis is now a common phenomenon in business environment and research. However, not a single company wants to reach in this situation because of its serious consequences on company and industry as well. Existing consumers lose their confidence on the affected company (Lei et al., 2008) and potential customers show negative purchase intention (Laufer and Gillespie, 2004) due to this situation. This situation also gives opportunity to competitors to become more aggressive and try to weaken the affected brand through various strategies (Tsang, 2000). Patanjali launch Ata (wheat flour) noodles before returning Maggie noodles after five month ban is one of the prominent examples of the same. More worsen; sometimes this negative situation affects the other brand of the affected company also (Heerde et al., 2005). Many times this product harm crisis not only affect the company that manufactured the defective product, but also affect the entire industry (Siomkos et al., 2010). Due to product harm crisis, smaller loss in consumer perceptions of a high-equity brand compared to low-equity brand (Rea et al., 2014). In the similar study, they investigated the degree of consumer reactions to the product-harm crisis, taking into consideration the level of brand equity. They recommended that Future researcher should consider other product type to investigate differences in consumer reactions.

The purpose of this study is to empirically investigate the degree of consumer reactions in terms of consumer attitude, consumer involvement, perceived quality, company credibility and intention to purchase to product-harm crisis, taking into consideration the low level and high level of brand equity. This study replicating the experimental methodology of Rea et al. (2014) conducted a similar study on PCs in United States. Experimental study is more appropriate for these type of studies(Rea et al., 2014; Mowen, 1980). India is developing country and less awareness in terms of brand as compare to developed nations like USA. For brands to strive and expand their brands to global market, it is essential to understand consumer preference for brands based upon level of economic development, ethnocentric bias, demographic characteristics of consumers, product type and product familiarity (Sengupta, 2014). For replicate the similar study, we have taken mobile phones among Indian consumers in order to validate those results in India. Mobile phone users in India increasing tremendously from 524.9 million in 2013 reach 730.7 million in 2017 and expected to reach 813.2 million by 2019 (www.statista.com). Mobile phone services have classified into both utilitarian and hedonic purposes. Utilitarian values of mobile phone relate to functional benefit and productivity while hedonic values refer to experiential and enjoyable ones (Yang and Lee, 2010).

Review of Related Literature and Hypotheses Development

Product harm crises can be defined as well-publicized incidences whereby products are found to be faulty, defective or dangerous (Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994) and result in terms of negative branding and market share erosion. It may also explain as “discrete, well-publicized occurrences wherein products are found to be defective or dangerous” (Dawar and Pillutla, 2000). The relevance of product harm crisis is increasing nowadays because of increasing complexity in production and continuous innovation. Standop and Grunwald (2009) defined as a general term representing product-related critical company condition involving public attention threatening the company’s reputation.

Numerous researchers have measured the product harm crises through various dimensions and their findings help marketers and researcher in better understanding of this situation. Siomkos et al. (2010) and Paswan et al., 2007 revealed that this crisis changes the consumer attitude and create opportunities for competitors. However, Roehm and Tybout (2006) explained that product harm crisis of establishing company may affect the whole industry. It is obvious that product harm crisis affects directly to the defected product but its potential negative impact also suffers to other products of the company also and thus it requires immediate corrective actions (Krystek, 1987). Benoit (1997) suggested five crisis communication strategies that marketer can adopt ranging from denial, corrective action and mortification, try to fix the problem, provide apologies and ask for forgiveness.

Researchers also pay attention towards the various magnitude and situations impacting product harm crisis. Laufer et al. (2005) assessed that perceived severity associated with product harm crisis have directly proportionate with observers’ attribution of blame to a firm. Consumer expectations play a moderating role in measuring the impact of product harm crisis on brand equity (Dawar and Pillutla, 2000). Cleeren et al. (2008) found that both pre-crisis loyalty and familiarity act as a shield against the product-harm crisis, although this elasticity diminishes with time. Empirical findings of Silvera (2012) explained that older consumers have a stronger purchase intention as compared with younger consumers. Standop and Grunwald (2009) suggested three way measures to handle the impact of such crisis. First is the communication through appropriate complaint management and customer recovery. Second are compensation measures such as offers or announcements of remedy and third are logistics measures comprised of organizational and technical infrastructure that is used to manage the crisis.

Since, this research is an attempt to replicate the experimental study of Rea et al. (2014) in Indian context. Similar hypotheses have been formulated to test consumer reaction towards product harm crisis. In this context, consumer reaction comprised of five elements: attitude toward the brand, involvement with the brand, perceived quality, company credibility and purchase intentions.

Attitude towards the brand or brand attitude have first explained by Fishbein and Ajzen, (1975) in the expectancy value model, This model vision attitude as the sum of all the significant beliefs hold by consumer for a product, multiplied by the strength of evaluation of each of those beliefs. A person holds a favourable attitude toward an object and then s/he will perform favourable behaviour with respect to the object and not to perform unfavourable behaviours (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977). Even though a few behaviours maybe have no evaluative implications for a given object, a negative evaluation will be an important predictor for implicating attitude toward the object (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977). After this, Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) and Ajzen(1988) measured the control of behaviour applied by the socio-physical environment and proposed the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). This theory is an attempt of predicting behavioral intention, spanning predictions of attitude and predictions of behavior. The consequent separation of behavioral intention from behavior allows for explanations of limiting factors on attitudinal influence (Ajzen, 1988). Miller (2005) defines each of these three components as attitude is the sum of all beliefs about the particular behavior influenceed by evaluations of these beliefs. It is obvious that product harm crisis affect consumer attitude and intention to purchase. Similar to developed countries brand attitude is an important dimension of measuring consumer behaviour, consumer reaction and purchase intention of developing countries like India (Vashisht and Chauhan, 2017; Sanyal et al., 2014; Punyatoya, 2012).

Brand involvement is “the degree of personal relevance that the product or purchase holds for that consumer” (Schiffman et al., 2010). Originally an involvement concept in consumer behaviour research was conceived in relation to how consumers responded to advertising (Krugman, 1965). Many consumer researchers have extended the use of involvement as its use to hold how consumers relate to products and brands (McWilliam, 1997; Costley, 1988). A good deal of research on Indian consumers discussed about the high and low involvement towards the brand impacts differently on consumer reactions such as consumer attitude and purchase intention (Khare, 2014; Mann and Kaur, 2013). Mathew and Thomas (2018) investigated brand loyalty as consumer reaction and consider brand involvement as a prominent construct for explaining the same. Brand involvement is associated with brand loyalty and impacts the level to which a consumer seeks information regarding brands and the nature of their brand loyalty (Simon and Walker, 2003; Howard and Sheth, 1969). Consumer involvement with the brand is temporary and reflects a situational consumer reaction during product harm crisis (Rea et al., 2014).

In order to attract customers, serve their needs and retain them, marketers and researchers are actively involved in understanding consumers’ expectations and perceptions of quality. Perceived quality may be defined as a continuous outcome created from developing of the product attributes that lead the consumers to make decisions about the product quality (Lindquist and Sirgy, 2003). In simpler words, perceived quality is a consumer’s judgment about the “superiority or excellence” of the product (Zeithaml, 1988). The relationship between brand equity and perceived quality was first established by Aaker (1991). He develops a brand equity model, comprised of five brand equity dimension and one of the dimension is perceived quality. Perceived quality of strong brands adds value to consumer’s purchase evaluations (Low and Lamb, 2000). Many studies in India measure consumer reations towards different level of brands or brand equity adopting Aaker (1991) model which comprised of perceived quality as an important variable (Bajpai and Khandelwal, 2012; Sanyal and Datta, 2011; Lee et al., 2010).

Company credibility is the consumer’s believability on the company due to its expertise and trustworthiness (Keller and Aaker, 1990). These expert and trust escorts by the number of successful products exist in the product line of the company. Company credibility is on a stake if product harm crisis occurs and it also generates negative reaction towards the product and the company as well. Company credibility is one of the significant dimension of measuring consumer reaction towards brand (Johnson and Kaye, 2016; Filieri, 2015). Company crediblity reviews have more impact on hedonic brand image rather than functional brand image in the context of consumer electronics product in India (Chakraborty and Bhat, 2018).

Purchase intention is an important outcome of consumer reaction towards any product and services. Companies are adopting various marketing strategies and improving quality in order to enhance purchase intention and sustainability (Khandelwal and Bajpai, 2012). There are numerous studies which measure the impact of a variety of issues on intention to purchase. In simple words, purchase intention may be defined as a plan to purchase a particular goods and services in coming future. Price and quality of the product directly influence product value and thus for improving value perception marketers focused on improving product quality and reducing price and consequently purchase intentions (Grewal et al., 1998). Consumer show various reactions in different situations, however product harm crisis is extreme circumstances result as a negative consumer reaction (Lei et al., 2012; Herbig and Milewicz, 1995; Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994). Huge amount of research in India on brand equity and purchase intention in different context. Punyatoya (2015) addressed that green brand equity lead to positive purchase intention among Indian consumers. Son et al. (2013). established attitude and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) had greater influence on Indian consumer’s purchase intentions toward foreign brand. Thamizhvanan and Xavier (2013) conducted an empirical study in India and found that Impulse purchase orientation and brand trust have significant impact on the customer purchase intention. Thus, the first hypothesis is proposed as

H1: There is a negative impact of product harm crisis in the context of the brand equity level on consumer attitude, consumer involvement, perceived quality, company credibility and intention to purchase.

Impact of product harm crisis varies with the level of brand loyalty and varies with different consumer groups. Many researchers explained that the negative impact was found to be less for a brand loyal customer or with high brand equity products (Lei et al., 2012; Van Heerde et al., 2007; Ahluwalia et al., 2000; Dawar and Pillutla, 2000). However, the literature also contradicts by suggesting that well establish brands and big companies have also been affected by product-harm crisis. The situation has become more worsen when consumer who switch to competitor brands become loyal to competitor products (Tsang, 2000). When consumers believe that a company break their trust, they possibly will not only turn against the specific brand of the company, but will also turn against the entire product line of the company (Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994). This leads the following hypotheses:

H2: There is a less negative impact of product harm crisis in the context of high equity brand on consumer attitude, consumer involvement, perceived quality, company credibility and intention to purchase as compare to low equity brand.

H3: There is no significance impact of consumer attitude, consumer involvement, perceived quality, company credibility on intention to purchase during pre and post product harm crisis.

Research Methodology

For investigating the above hypotheses, we select 217 consumer members between the age group of 20 and 30 years who intentionally take part in the analyses. Among them, 95 are females (44 percent) and 122 are males (56 percent). Every one of the members has at least finished their graduation. The examinations were completed utilizing two genuine individual mobile phone brands one is the high equity brand and other one is low equity brand mobile phone and confirm that the entire respondent heard these two brands. Then we ask to respondent to divide in the two groups because of the need of the experiment (High equity vs. low equity). Then, we go for the pre test the respondent ask to give their response to measure their attitude toward the brand, involvement with the brand, perceived quality, company credibility and purchase intention from these two group about their respective brands.

After conducting the pre test on these respondents than we showed short videos about 12 minutes approximately to these respondents about the product harm crisis of these brands. This video was comprised of the actual newscast of product harm related to mobile phone and overheating of the mobile phones and the blast of these mobile phones of these two brands in previous years. We cleared about the high equity or low equity brand video by mentioning the name at the starting, mid and at the end of the video. In this video, only this crisis was shown and we have not mentioned about the company involved in these crisis. These videos were designed to measure the actual response of the participant.

After showing these video, we asked the respondent to give their response on the same questionnaire (post test) about the attitude with the brand, brand involvement, perceived quality, company credibility and purchase intention of the respondent. A total of 217 respondents were available for the pre-test and post-test. Out of these 112 used for the high-equity brand and 105 for the low-equity brand.

In pre-test and post test, we measured consumer reactions in terms of attitude toward the brand, involvement with the brand, perceived quality, company credibility and purchase intentions. All these constructs except perceived quality have been measured by adopting the scale of Rea et al. (2014) who have used this scale for measuring the similar phenomenon on laptops and for perceived quality, we have used the scale of Agarwal and Teas (2001). This scale comprised of 11 items of attitude towards brand, 6 items of involvement with the brand, 3 items of perceived quality, 5 items of company credibility and 3 items of purchase intention. All 28 items were measured on seven point semantic differential scale consisting of pairs of opposite adjectives.

Results

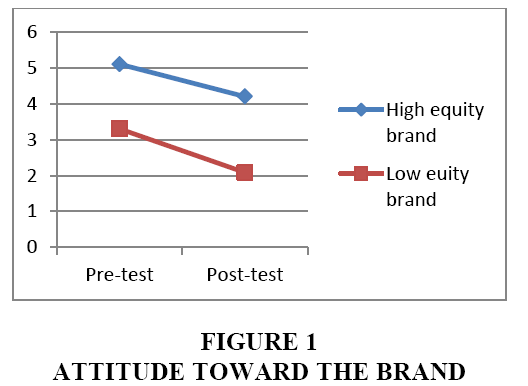

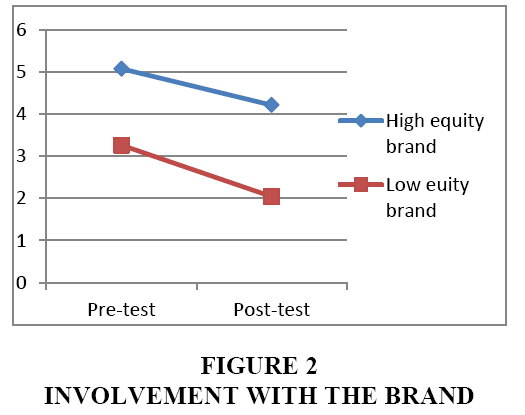

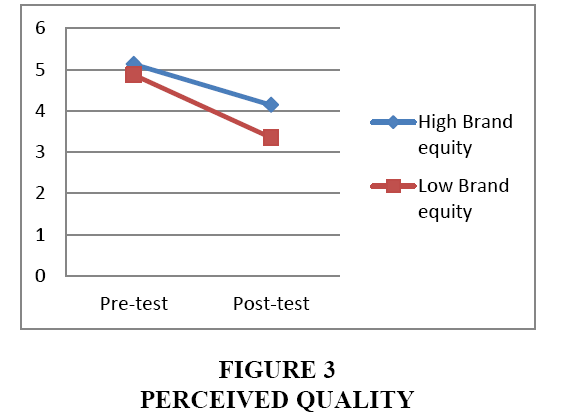

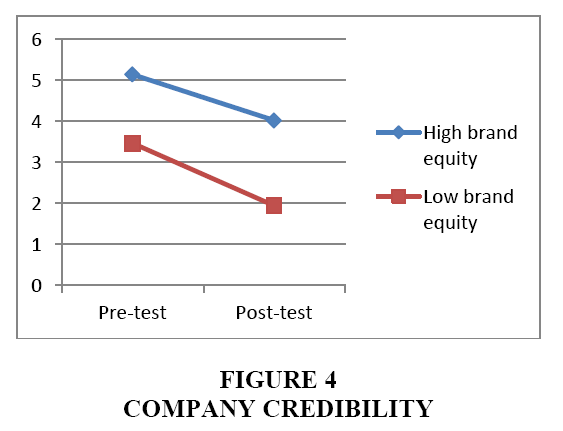

To test the H1, we conduct the various test on the feedback which was given by the respondent and we check multiple t-test to examine the mean difference between the pre-test and post-test for both the high equity brand and low equity brand. Our results shows that the post test mean is lower than the pre test mean and the mean test were statistically relevant for both the high equity brand (attitude: mean=5.1 vs. 4.2, t=4.23, p<0.01; involvement: M=5.07 vs. 4.21, t=3.935, p<0.01; perceived quality: M=5.13 vs. 4.14, t=9.39, p<0.01; company credibility: M=5.12 vs. 4.02, t=4.84, p<0.01; and purchase intentions: M=3.54 vs. 3.47, t=2.13, p<0.01) and the low equity brand (attitude: mean=3.3 vs. 2.08, t=5.68, p<0.01; involvement: M=3.26 vs. 2.04, t=4.73, p<0.01; perceived quality: M=4.87 vs. 3.35, t=17.64, p<0.01company credibility: M=3.06 vs. 1.94 , t=5.28, p<0.01; and purchase intentions: M=3.37 vs. 2.7 , t=2.11, p<0.01). Therefore H1 is supported by our analysis. The result are summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1 Pre and Post Test Comparison |

|||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Results of comparison | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean Difference | t | p | |

| High-equity brand | |||||||

| Attitude toward the brand | 5.1 | 1.25 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 4.23 | 0.000 |

| Involvement with the brand | 5.07 | 1.28 | 4.21 | 1.5 | 0.86 | 3.93 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Quality | 5.13 | 1.23 | 4.14 | 1.17 | 0.99 | 9.39 | 0.000 |

| Company credibility | 5.14 | 1.3 | 4.02 | 1.5 | 1.12 | 4.84 | 0.000 |

| Purchase intentions | 3.54 | 1.68 | 3.47 | 1.66 | 0.07 | 2.13 | 0.000 |

| Low-equity brand | |||||||

| Attitude toward the brand | 3.3 | 1.5 | 2.08 | 1.26 | 1.22 | 5.68 | 0.000 |

| Involvement with the brand | 3.26 | 1.6 | 2.04 | 1.4 | 1.22 | 4.73 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Quality | 4.87 | 1.2 | 3.35 | 0.8 | 1.52 | 17.64 | 0.000 |

| Company credibility | 3.46 | 1.6 | 1.94 | 1.19 | 1.52 | 5.28 | 0.000 |

| Purchase intentions | 3.37 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.67 | 2.11 | 0.000 |

H2 state that Consumer will rate a high-equity brand less negatively after a product harm crisis compared to low-equity brand. To investigate H2, we examined the t-test by comparing the post test mean of high equity brand with the post test mean of low equity brand. In our analysis we find that the mean equity of the four dependent measure were all higher for the high equity brand compare to the low equity brand and the difference is statistically relevant (attitude: mean=4.21 vs. 2.08, t=12.68, p<0.01; involvement: M=4.21 vs. 2.04, t=10.91, p<0.00; perceived quality: M=5.3 vs. 2.8, t=20.04, p<0.000; company credibility: M=4.02 vs. 1.94, t=11.13, p<0.01; and purchase intentions: M=3.47 vs. 2.7 , t=2.83, p<0.01). Therefore H2 is supported. The results are summarized in Table 2.

| Table 2 Comparison Of Post-Test Means Between Brands |

|||

| Results of comparison | |||

| Mean Difference | t | p | |

| Attitude toward the brand | 2.21 | 12.68 | 0.000 |

| Involvement with the brand | 2.17 | 10.91 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Quality | 2.57 | 20.04 | 0.000 |

| Company credibility | 2.08 | 11.13 | 0.000 |

| Purchase intention | 0.77 | 2.83 | 0.000 |

To examine H3, we applied multiple regression by taking Purchase Intention (PI) as dependent variable and attitude toward the Brand Attitude (BA), Brand Involvement (BI), Perceived Quality (PQ) and Company Credibility (CC) as dependent variables for high brand equity case and low band equity case separately. Both the regression result established the significant relationship between independent variables (BA, BI, PQ, CI) and dependent variable PI as all the p-values are significant in both the cases. Significant p-value corresponding to t-value is an indication of good linear relationship between dependent variable (purchase intention) and independent variables in both pre and post experiment. This supports that there is significance impact of BA, BI, PQ and CC on Purchase Intention (PI). Coefficient of determination (R2) is decreasing from pre-test (56.6%) to post test (44%) in high brand equity product and from pre-test (51%) to post test (23.9%) in low brand equity product reflects that product harm crisis impact negatively on consumer reactions in both the cases. However, low brand equity product is more negetively affected by product harm crisis.

Table 3: Regression coefficient, t-value, R2 value, F-value and p-value for the regression result between Purchase Intention (PI) and Brand Attitude (BA), Brand Involvement (BI), Perceived Quality (PQ) and Company Credibility (CC) taken for the study in high brand equity product.

| Table 3 Regression Result For High Brand Equity Product |

|||||||||

| S.No. | Var | Pre test | Post test | ||||||

| Coefficients | Std. Error | t-stat | p-value | Coefficients | Std. Error | t-stat | p-value | ||

| 1 | BA | 0.221 | 0.0262 | 8.433 | 0.000 | 0.230 | 0.036 | 6.329 | 0.000 |

| 2 | BI | 0.239 | 0.0284 | 8.443 | 0.000 | 0.267 | 0.039 | 6.786 | 0.000 |

| 3 | PQ | 0.153 | 0.0320 | 4.759 | 0.000 | 0.186 | 0.045 | 4.187 | 0.000 |

| 4 | CC | 0.227 | 0.0282 | 8.053 | 0.000 | 0.225 | 0.039 | 5.744 | 0.000 |

| R2 value | 0.566 | 0.440 | |||||||

| F value | 69.127 | 41.633 | |||||||

| p value for F value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

Table 4: Regression coefficient, t-value, R2 value, F-value and p-value for the regression result between Purchase Intention (PI) and Brand Attitude (BA), Brand Involvement (BI), Perceived Quality (PQ) and Company Credibility (CC) taken for the study in low brand equity product.

| Table 4 Regression Result For Low Brand Equity Product |

|||||||||

| S.No. | Var | Pre test | Post test | ||||||

| Coefficients | Std. Error | t-stat | p-value | Coefficients | Std. Error | t-stat | p-value | ||

| 1 | BA | 0.191 | 0.027 | 7.093 | 0.000 | 0.144 | 0.055 | 2.635 | 0.009 |

| 2 | BI | 0.212 | 0.029 | 7.281 | 0.000 | 0.238 | 0.059 | 4.018 | 0.000 |

| 3 | PQ | 0.156 | 0.033 | 4.725 | 0.000 | 0.321 | 0.067 | 4.797 | 0.000 |

| 4 | CC | 0.217 | 0.029 | 7.488 | 0.000 | 0.149 | 0.059 | 2.528 | 0.012 |

| R2 value | 0.510 | 0.239 | |||||||

| F value | 55.202 | 16.717 | |||||||

| p value for F value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

Discussion

This paper measure the change in the degree of consumer reactions after product harm crisis, taking into consideration the level of brand equity among Indian consumers. Consumer reactions have measured empirically by considering four different construct brand attitude, brand involvement, perceived quality, company credibility and purchase intention. As our belief, our findings were also shown similar result that product harm crisis has a greater negative impact over low brand equity.

In detail explanation of our hypothesis testing, results show that product harm crisis laid negative impact on brand attitude, brand involvement, perceived quality, company credibility and purchase intention in both lower brand equity as well as higher brand equity as shown in Table 1. This result supports our first hypothesis. Thus, companies have to show proactive behaviour in order to reduce product harm crisis and also recover the positive consumer reaction by better management after crisis. This management not solely based on brand equity level.

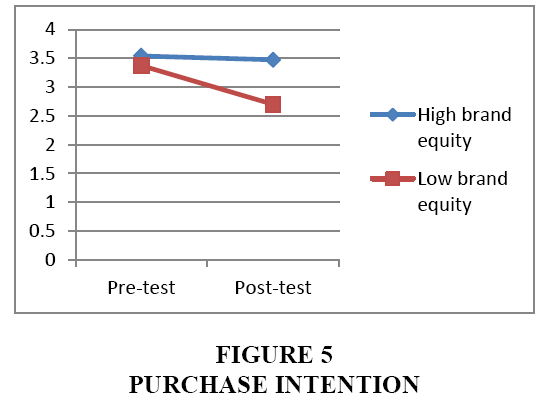

However, if we analyze the mean difference in terms of brand equity level, then the impact of this dent is lower in high brand equity segment as compared to the low brand equity. So, we can say that level of brand equity plays a role of shield during product harm crisis. This also supports our second hypothesis. Our third hypothesis was also supported which explain Brand Attitude (BA), Brand Involvement (BI), Perceived Quality (PQ) and Company Credibility (CC) is positively affected purchase intention of high brand equity as well as low brand equity product. In discussion with construct wise, company credibility and perceived quality have a higher negative impact in both categories, i.e. high level of brand equity and low level of brand equity. As expected, company credibility obviously suffers during product harm crisis. So, companies have to focus on strengthening credibility during product harm crisis because once the credibility lost it require huge cost and time to regain the same (Herbig and John-Milewicz, 1995). One interesting findings emerged from our analysis that there is no difference in the purchase intention of high brand equity products between pre and post harm crisis. This finding is consistent with the findings of Rea et al. (2014) that high-equity, brand maintains higher trust than that of a low-equity brand even in product-harm crisis situation. However, in the case of low brand equity, purchase intention is greater negatively affected. This shift is clearly shown in Figures 1-5 and through this we can say that developing a strong brand is one of the best solution for unexpected product crisis. Strong brands own by its consumer and they feel affected during the crisis and thus do not leave the brand as compare with weak brands (Kotzegger and Schlegelmilch, 2013).

Comparison of Brand Equity Effects

Customer perceives, that firm has a control over such failure, but fails to exercise that control or this may happen in the future again, then they hold company an offender for such failure (Huang, 2008). Wirtz and Mattila (2004) confirmed the similar finding and given the extention that a customer’s perception of a firm’s responsibility has a significant influence of customer satisfaction evaluations.

However, in accordance with the attribution theory, consumers will evaluate product failure due to two major causes, internal-in control of the firm and external-not in control of the company. So, whenever there may be some external reasons involve in crisis, there is a greater propensity to blame external factors to save firms integrity. We have seen this in the case of high level of pesticides and insecticides found in soft drinks and honey in India. Involve companies blame the external factors in this incident. Thus, in a high brand equity firm faces product harm crisis, the customer of the firm are expected unreliable with company norms and blame external factors for such crisis. Product harm crisis is a low reliability performance for a high-equity brand firms (Rea et al., 2014).

Most of the research investigated business dimensions during stability in different conditions (Barker and Gimpl, 1988). However, occurrence of crisis may shift the consumer attitude and purchase intention from the harmful products to the competitor’s one. This is a severe situation for any company. There are two ways to protect the company from this situation. First, the proactive approach, which states that to manage every dimension of your product from development to service in such a manner that company, should not face any form of crisis. Second one is the curative measure and this should identify potential allies and rivals among their stakeholder groups, including consumers, regulatory agencies, media and competitors (Siomkos et al., 2010). Finding of this study gives the more concrete solution in the form of prevention and curative measures as well and this is to make your product into a strong brand. During the time of the crisis, companies try to win back the trust of consumers and investors. The business performance of the company originates from the consumer performance. For doing this cost could be one of the most considerable issues, but it is not an impossible task. Companies can build the brand up slowly by investing in corporate social responsibility activities, proper use of social networking sites, mark up as a credible endorser, effective public relations, etc. Similar suggestions proposed by Zhao et al. (2011) that strong brands spots on short-term sales in order to boost consumer exposure, resulting in restoring trust in the brand and weak brands spots on increasing the perceived quality level of their product among consumers.

Conclusion

This paper has sought to explore product harm crisis on consumer reaction. Because of heavy use of technology, rapid supply, meeting customer expectations in competitive world and huge competition, product harm crisis become a common phenomenon now a days. But this non welcome phenomenon ruins the company’s image and its efforts. This research is the survey based exploratory research in order to measure the impact of product harm crisis on consumer reactions with respect to different level of brand equity. Empirical results show that product harm crisis laid negative impact on brand attitude, brand involvement, perceived quality, company credibility and purchase intention in both lower brand equity as well as higher brand equity. Results can say that say that level of brand equity plays a role of shield during product harm crisis. Company credibility and perceived quality have a higher negative impact in both categories, i.e. high level of brand equity and low level of brand equity. As expected, company credibility obviously suffers during product harm crisis. So, companies have to focus on strengthening credibility during product harm crisis because once the credibility lost it require huge cost and time to regain the same. One interesting findings emerged from our analysis that there is no difference in the purchase intention of high brand equity products between pre and post harm crisis. Strong brands own by its consumer and they feel affected during the crisis and thus they do not leave the brand as compare with weak brands. Companies have to manage product harm crisis phenomenon with greater consumer concern so that the minimum dent will happen in their business operations.

Impact of product harm crisis on different level of brand equity is the extensive and complex phenomenon as undergoing constant and rapid development, hence representing a challenging task for research. This entails that a number of limitations can be presented, of which the most substantial are elaborated upon. However, some of these limitations can and should also be regarded as fruitful avenues for future research under a similar scope. This experimental research to measure consumer reaction during pre and post product harm crisis by considering two different brands of mobile phone. However, consumer reaction may be different for different categories of product and utilitarian level. Future researchers may consider different product categories and utilitarian level to measure consumer reaction during product harm crisis. This study considers brand equity level only in measuring consumer reactions during product harm crisis. Future researchers may consider some more product and service related dimensions. Another limitation of this study is that, this study presents the immediate effect on consumer reactions. Future researchers may go for a longitudinal study to measure the elongated negative effects of product harm crisis.

References

- Aaker, D.A. (1991). Managing brand equity. New York: The Free Press.

- Aaker, D.A., & Keller, K.L. (1990). Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 27-41.

- Ahluwalia, R., Robert, E., Burnkrant, and H-Rao, U. (2000). Consumer response to negative publicity: the moderating role of commitment. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(3), 203–214.

- Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality and behavior, (Second Edition). Chicago: Dorsey Press.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior, (First Edition). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein. M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888-918.

- Ambler, T. (1997). How much of brand equity is explained by trust? Management Decision, 35(4), 283-292.

- Aulakh, G. (2016). Samsung India stares at 14% revenue hit for 2016 post Note 7 debacle: CMR. Economictimes.indiatimes.com.

- Bajpai, N., & Khandelwal, U. (2012). Understanding brand equity by metro and non-metro consumers and its impact on consumer attitude: a comparative study in indian perspective. IMS-Manthan: The Journal of Innovation, 7(2), 47-53.

- Barker, T., & Gimpl, M.L. (1988). What's new? opportunities and strategies for businesses. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 6(3), 14-20.

- Benoit, W.L., & Czerwinski, A. (1997). A critical analysis of USAir’s image repair discourse. Business Communication Quarterly, 60 (3), 38-57.

- Cleeren, K., Dekimpe, M.G., & Helsen, K. (2008). Weathering product-harm crises. Journal of the Academy Marketing Science, 36(2), 262-270.

- Costley, C.L. (1988). Meta analysis of involvement research. Advances in Consumer Research, 15(1), 554-562.

- David-H.,S, Tracy, M., & Daniel, L., (2012). Age?related reactions to a product harm crisis. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(4), 302-309.

- Davies, G., Chun, R., Da-Silva, R.V., & Roper, S. (2003). Corporate reputation and competitiveness, (First Edition). New York: Routledge.

- Dawar, N., & Pillutla, M.M. (2000). Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 215-226.

- Filieri, R. (2015). What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative in fluences in e-WOM. Journal of Business Research, 68(6), 1261-1270.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research (First Edition). Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

- Grewal, D., Krishnan, R., Baker, J., & Borin, N. (1998). The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers' evaluations and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74(3), 331-352.

- Heerde, H.J., Helsen, K., & Dekimpe, M.G. (2005). Managing product-harm crises-research paper ERS-2005-044-MKT, Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM). Erasmus University and Erasmus School of Economics, Rotterdam, 69(3), 309-329.

- Herbig, P., & Milewicz, J. (1995). To be or not to be credible that is: A model of reputation and credibility among competing firms. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 13(6), 24-33.

- Howard, J.A., & Jagdish, N.S. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior, (Second Edition). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Johnson, T.J., & Kaye, B.K. (2016). Some like it lots: The influence of interactivity and reliance on credibility. Computers in Human Behavior, 61(1) , 136-145.

- Khandelwal, U. & Bajpai, N. (2015). Measuring consumer attitude through marketing dimensions: A comparative study between metro and non-metro cities. Jindal Journal of Business Research, 2(2), 1-19.

- Khare, A. (2014). How cosmopolitan are Indian consumers? A study on fashion clothing involvement. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 18(4), 431-451.

- Kotzegger, U., & Schlegelmilch, B.B. (2013). Conceptualizing consumers' experiences of product?harm crises. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(2), 112-120.

- Krugman, H.E., (1965). The impact of television advertising: Learning without involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 29(3), 349-356.

- Krystek, U. (1987). Description, prevention and management of survival critical processes in companies, (First Edition). Gabler, Wiesbaden.

- Laufer, D., & Gillespie, K. (2004). Differences in consumer attributions of blame between men and women: The role of perceived vulnerability and empathic concern. Psychology & Marketing, 21(2), 141-57.

- Laufer, D., Gillespie, K., McBride, B., & Gonzalez, S. (2005). The role of severity in consumer attributions of blame: defensive attributions in product-harm crises in Mexico. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 17(3), 33-50.

- Lee, H. J., Kumar, A., & Kim, Y.K. (2010). Indian consumers' brand equity toward a US and local apparel brand. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 14(3), 469-485.

- Lei, J., Dawar, N., & Gurhan-Canli, Z. (2012). Base-rate information in consumer attributions of product-harm crises. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(3), 336-348.

- Lei, J., Dawar, N., & Lemmink, J. (2008). Negative spillover in brand portfolios: Exploring the antecedents of asymmetric effects. Journal of Marketing, 72(3), 111-123.

- Lindquist, J.D., & Sirgy, J.M. (2003). Shopper, buyer and consumer behavior: Theory and marketing applications, (Second Edition). Biztantra, New Delhi: Dreamtech Press.

- Low, G.S., & Lamb, C.W. Jr (2000). The measurement and dimensionality of brand associations. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 9(6), 350-368.

- Mann, B.J.S., & Kaur, M. (2013). Exploring branding strategies of FMCG, services and durables brands: evidence from India. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 22(1), 6-17.

- Mathew, V., & Thomas, S. (2018). Direct and indirect effect of brand experience on true brandloyalty: Role of involvement. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(3), 725-748.

- McWilliam, G. (1997). Low involvement brands: Is the brand manager to blame? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 15(2), 60-70.

- Miller, K. (2005). Communications theories: Perspectives, processes, and contexts, (First Edition). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Mowen, J. (1980). Further information on consumer perceptions of product recalls. Advances in Consumer Research, 7(2), 519-523.

- Number of mobile phone internet users in India from (2015-2022) (in millions). Retrieved from www.statista.com.

- Paswan, A.K., Spears, N., & Ganesh, G. (2007). The effects of obtaining one’s preferred service brand on consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty. Journal of Services Marketing, 21(2), 75-87.

- Punyatoya, P. (2015). Effect of perceived brand environment-friendliness on Indian consumer attitude and purchase intention: An integrated model. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(3), 258-275.

- Rea, B., Yong, J., & Wang, J.S. (2014). When a brand caught fire: the role of brand equity in product-harm crisis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23(7), 532-542.

- Roehm, M.L., & Tybout, A.M. (2006). When will a brand scandal spillover and how should competitors respond? Journal of Marketing Research, 53(3), 366-373.

- Sanyal, S.N., & Datta, S.K. (2011). The effect of perceived quality on brand equity: An empirical study on generic drugs. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 23(5), 604-625.

- Sanyal, S.N., Datta, S.K., & Banarjee, A.K. (2014). Attitude of Indian consumers towards luxury brand purchase: An application of attitude scale to luxury items. International journal of Indian Culture and Business Management, 9(3), 316-339.

- Schiffman, L.G., Kanuk, L.L., & Wisenblit J. (2010). Consumer behavior, (Tenth Edition).Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Pearson - Prentice Hall.

- Sengupta, A. (2014). Brand analyses of global brands versus local brand in Indian. Retrieved from https://uknowledge.uky.edu/mat_etds/6

- Silvera, D.H., Meyer, T., & Laufer, D. (2012). Age?related reactions to a product harm crisis. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(4), 302-309.

- Simon, K., & Walker, D. (2003). Empirical developments in the measurement of involvement, brand loyalty and their relationship in grocery markets. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 11(4), 271–286.

- Siomkos, G., Triantafillidou, A., Vassilikopoulou, A., & Tsiamis, I. (2010). Opportunities and threats for competitors in product?harm crises. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(6), 770-791.

- Siomkos, G.J., & Kurzbard, G. (1994). The hidden crisis in product-harm crisis management. European Journal of Marketing, 28(2), 30-41.

- Siomkos, G.J., & Malliaris, P. (1992). Consumer response to company communications during a product-harm crisis. Journal of Applied Business Research, 8(2), 59-65.

- Son, J., Jin, B., & George, B. (2013). Consumers' purchase intention toward foreign brand goods. Management Decision, 51(2), 434-450.

- Standop, D., & Grunwald, G. (2009). How to solve product?harm crises in retailing? Empirical insights from service recovery and negative publicity research. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(11), 915-932.

- Thamizhvanan, A., & Xavier, M.J. (2013). Determinants of customers' online purchase intention: an empirical study in India. Journal of Indian Business Research, 5(1), 17-32.

- Tsang, A.S.L. (2000). Military doctrine in crisis management: Three beverage contamination cases. Business Horizons, 43(5), 65-73.

- Van-Heerde, H., Helsen, K., & Dekimpe, M.G. (2007). The impact of product-harm crisis on marketing effectiveness. Marketing Science, 26(2), 230-245.

- Vashisht, D., & Chauhan, A. (2017). Effect of game-interactivity and congruence on presence and brand attitude. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 35(6), 789-804.

- Yang, K., & Lee, H.J. (2010). Gender differences in using mobile data services: utilitarian and hedonic value approaches. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 4(2), 142-156.

- Zeithaml, V.A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2-22.

- Zhao, Y., Zhao, Y., & Helsen, K. (2011). Consumer learning in a turbulent market environment: Modeling consumer choice dynamics after a product-harm crisis. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(2), 255-267.