Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Measurement of Intangible Human Elements of Military Combat Readiness

Inderjit S, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Hasan Al-Banna Mohamed, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Kwong FW Jesscia Ong Hai Liaw, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Abdul Rahman Abdul Razak Shaik, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Safar Yaacob, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Wong Wai Loong, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Ummul Fahri Abdul Rauf, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Siti Najwa, Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia

Keywords

Combat Readiness, Military Psychological Factors, Quality Of Life, Morale.

Abstract

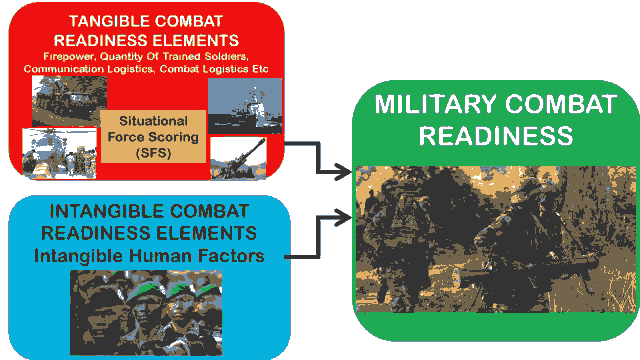

The dominant engagement and involvement of military forces are relevant to foresee the sovereignty of the country in encapsulating both internal and external threats lingering at all times. Different militaries globally have always concluded the different perspectives of understanding and theoretically defining combat readiness. Realistically combat readiness is subjected to their military doctrine, policies, and public communications in the preparedness of their military forces for combat duties. The Malaysian Armed Forces use the Situational Force Scoring (SFS) quantitative measurement of combat readiness of troops whereby numerical tangible scores are given in terms of percentages of logistics, and manpower requirements. Unfortunately, the soldiers in terms of individuals’ intangible human dimension factors are not quantified such as morale, quality of life, and military psychological factors which invariably are of utmost importance for the military prior to combat duties. This mix method research will relook at the current systematic framework model of combat readiness and propose a synchronized hybrid measurement of both tangible and intangible assessment for combat readiness model for the military which can be replicated and used by other security agencies which can adopt the same model for their operational preparedness such as the Royal Malaysian Police, Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency and other relevant security forces in Malaysia.

Background

All security forces in the world have operational readiness for their troops to be prepared for any duties both local and overseas. Since different militaries engagement different quantitative formulae for measuring combat readiness there is a conceptual requirement to innate the tangible and intangible elements in preparing troops for combat duties. The measurement of intangible elements needs to be accounted in tandem with the tangible elements such as firepower, logistics, manpower and other supplementary elements.

The complete hybrid of both elements will provide a comprehensive measurement of the status of combat readiness. The amount of training time of a military group operates correlates to the operational readiness especially when more training time is allocated or given for the operational unit (Meijer, 1998). The readiness and ability of a military force in all situational conditions and environment at a given time to accomplished any mission given is commonly defined according to their situational awareness assumptions and configuration of the current scenario in that country (Yurechko, 2007).

The scenario of the combat environment and the readiness of the team is linked to the soldier’s military training in both individual and collective training. It was determined by the fighting efficiency and battle-worthiness of troops (forces), by a correct understanding of their commanders, staff and political agencies, by prompt and timely preparation for forthcoming operations, and by foreseeing possible situation changes (Meijer, 1998). The degree of combat readiness in peacetime would ensure a rapid shifting of troops (forces) to a war alert status and organized commencement of military operations, and in wartime the ability to accomplish immediate execution of assigned combat mission. This research will quantity the intangible combat readiness elements into an instrument assessment measurement so that preventive measures and also corrective measures can be undertaken after establishing the score of an individual, unit and an organization. The outcome of this research is to develop a systematic model and framework assessment tool for all Malaysian Security agencies. This instrument that will be able to measure the combat readiness of intangible factors of units to be deployed in combat areas, humanitarian assistance such as natural disaster assistance, peacekeeping operations such as the current military deployment in Lebanon and national security operations such as the intrusion in Lahad Datu in 2013.

Introduction

The Malaysian National Defence Policy reflects the continued commitment towards strengthening the National Defence and Malaysian Armed Forces modern technical transformation (Malaysian National Defence Policy, 2014). The nucleus of national policy strategy consists of military preparedness as a major contributor to national power (Creswell, 2014). The five pillars for Malaysia to develop their Armed Forces is showcased in jointers, interoperability, technology based, able to operate simultaneously in two theatres and mission-orientated (Defence White Paper, 2020). Future defensive posture requires a military force which is ready for any eventualities in responding to any threats. The military combat readiness is relevant in ensuring the nation’s security, sovereign and prosperity (Defence White Paper, 2020). The military combat readiness aspect is the measuring of material readiness, personnel in terms of their readiness and numbers on standby duties, and the training aspects of the soldiers in both individual and collective training (De Both, 1984). Preparedness of soldiers for operational and combat duties requires the balanced equation of combat logistics in terms of manpower, firepower, training capabilities of soldiers in different scenarios of combat convention, and other military duties such as the peacekeeping force in the United Nations. Malaysian is ranked eighth among troop contributors to the United Nation peacekeeping forces in Asia and currently contributing 819 troops to the UN particularly in United Nation in Lebanon. The total number of Malaysian UN peacekeepers deployed in the Eastern Mediterranean since 2017 is 10,840 men and women (Malaysian Army, 2019). As such preparing the soldiers before international combat duties is essential so that the training conducted will comply with the requirements needed especially in the measurement of both the tangible and intangible elements of combat readiness. The combat readiness also includes the measurement of soldier preparedness in terms so intangible human elements such as morale, leadership, spirit de corps, quality of life, psychological factors, and other factors which need to be equated to complete the equation (Inderjit, 2014).

As such this research will study the current measurement assessment model formulae of measuring combat readiness and the current applications of such dimensions before combat duties by the Malaysian Armed Forces. Currently, the combat readiness measurement application is in piecemeal and there is a need to provide a quantitative measurement of both logistics and the human intangible elements to complete the measurement assessment tool for measuring combat readiness before operational requirements at any given time. The objective of this research is to address the current gap of assessment in security forces and propose a systematic model and developing an assessment instrument to determine the intangible human dimension of combat readiness of all security forces. Currently, there is no assessment of intangible human factors assessment for security forces personnel on their preparedness for combat or operational duties. The outcome of this research is developing a validated and reliable instrument to measure the intangible factors about morale, quality of life, and psychological factors with a designated scoring worksheet to determine the status of individual readiness for units namely the Malaysian Army, Royal Malaysian Air Force, Royal Malaysian Navy, Royal Malaysian Police, Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency and other relevant security forces in Malaysia to work in cohesion and provide some distinctive operations procedures as an agency or in teams working together in any operations both local and international duties.

Combat Readiness

The combat readiness aspect is measuring material readiness, personnel in terms of their readiness and numbers on standby duties, and the training aspects of the soldiers in both individual and collective training (De Both, 1984). The amount of training time a military group operates correlates to operational readiness especially when more training time is allocated or given for the operational unit (Meijer, 1998). According to (Yurechko,2007) military forces should be consistently maintained and capable of deploying at a high state of readiness and repulsing enemy surprised exploitation and accomplishing success. Combat is defined as “the arrangement of personnel and the storage of equipment and supplies in a manner designed to conform to the anticipated tactical operation of the organization embarked” and each item is stowed so that it can be unloaded at the required time” (North Atlantic Treaty Organization,2013). Readiness is a term regularly applied to the United States’ “ability to produce, deploy, and sustain military forces that will perform successfully in combat” (Herrera, 2020). The important human factors and systematic, systemic psychosocial involvements lead to the conservation of combat readiness (Meijer & de Vries, 2005). In a research conducted in Royal Nederland’s Navy of eight naval sea outbound units, it was derived that personnel readiness of soldiers is measured by the quality and quantity of the individuals and the amount of time they were in overseas for combat duties. It is also denoted that training and individual readiness are the key factors in the maintenance of combat readiness (Meijer & de Vries, 2005). The degree of measuring combat readiness is affiliated to a numerical number or percentage (quantitative) and other verbal descriptors (qualitative) (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Such measurement on variables must be assigned with a number based on a given set of rules Hair et al., (2011). At such measurement of combat readiness do not have a standardized measurement model and tool as each military have their own set of procedures, doctrines, and policies incumbent to the niche requirements. Current doctrine defines readiness as “the ability of military forces to fight and meet the demands of assigned missions.” (Margaret, 2017). Richard Betts describes readiness as “a measure of the pre-D-Day status of the force” and “a force’s ability to fight with little or no warning.” (Betts, 1995).

Different militaries globally have always concluded the different perspectives of understanding and theoretically defining combat readiness. This realistically is subjected to their military doctrine, policies, and public communications in the preparedness of their military forces for combat duties. The readiness and ability of a military force in all situational conditions and environments at a given time to accomplish any mission given is commonly defined in the Russian Armed Forces (Yurechko, 2007). The scenario of the combat environment and the readiness of the team are linked to the soldier’s military training in both individual and collective training. According to (Yurechko,2007) military forces should be consistently maintained and capable of deploying at a high state of readiness and repulsing enemy surprised exploitation, and accomplishing successful mission offensive operations. But there is a need for quantifying the percentages of combat readiness so that gaps can be consolidated and provide a stronger force for combat engagements.

The combat readiness preparedness in peacetime means troops need to be standby ready for combat requirement duties at any time to accomplish combat mission duties. The term operational readiness is defined as “the capability of a unit/formation, ship, weapon system, or equipment to perform the missions or functions for which it is organized or designed (Betts, 1995).” Structural readiness is looking at the broader aspect of the military force and its composition and their readiness to de deployed for a mission. The critical relationship between both concepts of readiness is the overall force capabilities currently and in the future. The speed and ability of a unit to be deployed to combat duties are not recognised only as readiness. There are examples when readiness complies with the quick deployment but the readiness on the unit in battle was a failure. Some examples of rapid deployments with troops not prepared for the combat duties range from Japanese naval airpower in the Pacific during World War II to the debacle of Task Force Smith during the Korean War and the more recent early rotations of U.S. forces in Iraq.

The combat readiness aspect is measuring material readiness, personnel in terms of their readiness and numbers on standby duties, and the training aspects of the soldiers in both individual and collective training (De Both, 1984). The amount of training time a military group operates correlates to operational readiness especially when more training time is allocated or given for the operational unit (Meijer, 1998). The important human factors and systematic, systemic psychosocial involvements lead to the conservation of combat readiness (Meijer & de Vries, 2005).

In a research conducted in Royal Nederland’s Navy of eight naval sea outbound units, it was derived that personnel readiness of soldiers is measured by the quality and quantity of the individuals and the amount of time they were in overseas for combat duties. It is also denoted that training and individual readiness are the key factors in the maintenance of combat readiness (Meijer & de Vries, 2005). The different theories of combat readiness depict a unique proficiency and capabilities of a military unit. The tangible elements provide the military assets and competency with the complimentary intangible elements which this research is embarking namely morale, quality of life, and psychological factors. The deployment measurement of combat readiness is correlated to the unit preparedness which has been planned or maybe a collective combination of military assets and individual morale (Voith, 2001; Andrew & Shambo, 1980). Past research concluded that besides the military assets and capabilities other factors namely the morale of soldiers are essential when preparing and deployment of a combat mission (Bester & Stanz, 2007; Gal, 1986; Schuman et al, 1996). Research has also concluded that intangible elements such as morale and quality of life are important in the measurement of combat readiness (Bester & Stanz, 2007; Gal, 1986; Schuman et al., 1996).

The definition of combat readiness has many clouds of meaning according to academicians and militaries. The indication for readiness is comparatively mixed as different definitions are used for the diverse research conducted by militaries globally (Schumm, 1996) Some of the definitions of combat readiness by various academicians are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Various Definition Of Combat Readiness |

|

|---|---|

| Definition of Combat Readiness | Author |

| Combat readiness is associated with numerical values (quantitative) or verbal descriptors in qualitative research | (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) |

| The ability of military forces to fight and meet the demands of assigned missions.” | US Department of Defense,2017 |

| “The deployment measurement correlated to the unit preparedness which has been planned or maybe a collective combination of military assets and individual morale” | (Voith, 2001; Andrew & Shambo, 1980). |

| “The readiness and ability of a military force in all situational conditions and environment at a given time to accomplished any mission given is commonly defined in the Russian Armed Forces” | Yurechko,2007 |

| “A psychological attribute in terms of a soldier’s choice or degree of commitment to, and persistence in effecting a certain course of action” | Gal (1986) |

| “Combat readiness acts as an inadequate bridge between motivation and morale within the military context” | Lord Moran’s statement (cited in Richardson, 1978) |

| “Conceptualised the term “human readiness for combat” in terms of three variables, namely Individuals’ Mental Readiness, Unit Readiness, and Actual Performance in Combat”. | MacDonough and Blankinship (cited in MacDonough, 1991) |

| “Combat readiness as the concept as the state of preparedness of a unit to perform its assigned role” | Ministry of Public Works and Government Services of Canada (1997) |

| “Combat readiness as the measure of a force conducting operations successfully against a hostile force”. | Lutz (1997) |

| “Generalship, leadership, operational and tactical planning and execution, logistics, intelligence and a host of other factors are critical for combat performance” | Hooker (1998) |

| “Combat readiness as a grocery list for war with quantifiable items that can be tallied bought and paid for” | Summers (1998) |

| “Combat readiness in the US Army is measured by resources such as soldiers, leaders, equipment, ammunition, and fuel. These resources, however, simply enable readiness and have always been an inadequate yardstick for readiness. Therefore he argues that the moral dimension should also be included” | Rosenberger (1999) |

Situational Force Scoring (SFS) is the quantitative measure by enhancing the numerical score on readiness by reflecting on the battle terrain, combat requirements, and combined arms imbalance or shortages (Allen, 1987). Inevitably the combination of numerical scores for both tangible and intangible elements is paramount to complete the combat readiness of the unit preparing for combat duties. According to Allen (1992), Situational Force Scoring (SFS) is a tool to provide a representation of ground forces in close combat using combat models with numerical scores to compute force ratio, attrition, and movement. SFS provides an alternative mechanism in figures on varying data to adjusting the score line to reflect the type of environment or terrain, type of battles, and the combined imbalances or shortages on military units on combat duties. For example, infantry in prepared defences in urban or mountainous terrain can be very effective against armour, but this relative effectiveness is ignored in aggregate combat models, which do not account for this situation (Figure 1).

The Malaysian Army measures combat readiness using the Situational Force Scoring (SFS) and their objective is to complete the tangible requirement of troops, manpower, and combat logistics such as firepower, training, and another quantitative measure of support need in aggregate to specific mission requirements as shown in Figure 1 on the tangible and intangible element of combat readiness. The strength of this measurement tool is this is measurable and defence management can plan and breach the percentage requirements in number s and percentage to envisage the preparedness of the unit for combat duties. Unfortunately, this method does not foresee the intangible human dimension factors in an individual soldier liberating into collective teams for mission duties.

The Intangible Human Elements of Combat Readiness

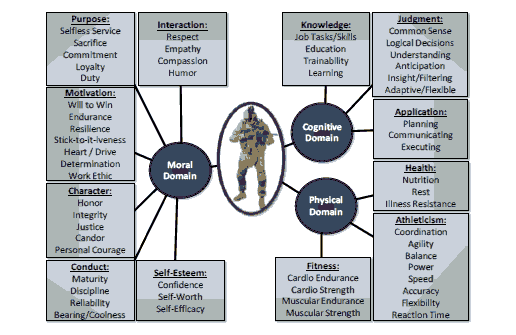

The components that provide the exclusive intangible elements in a soldier are associated with the human dimension which incorporates the moral, physical, and cognitive dimensions. The other antecedent’s requirements are focus on the ability, performance, and attitudes of the individual soldier and incorporate other members of his team before combat duties. The concept of holistic fitness is trivial to the soldier’s readiness from all aspects in individual military training to collective team cohesiveness, the desire in motivation and well-being for all military requirements. The military is consistently seeking soldiers with incomparable cognitive, physical and social (Morale & Cultural) competencies. The inclusion of technology-enhanced with medical sciences has catapulted the complex operational environment requirements (Dees, 2010). Soldiers are needed to adapt and retain skills necessary in technology advancement and processes that optimize and restore cognitive and physical performance. US Military Academy, Department of Systems Engineering, West Point researched the Whole Soldier Performance (Dees, 2006) which displays the final functional hierarchy of US soldier performance attribute groupings in the moral, cognitive, and physical domains as seen in Figure 2.

Morale

Morale has been defined by the US Military Leadership,1993 as a “mental, emotional and spiritual frame in a unit”. Van Dyk (2015), defines morale as “The confident and positive frame of mind and motivation existing in an individual, endurance and readiness for complete commitment to the common goal pursued by group, especially in the face of difficult and complex conditions, i.e. at time of proceeding military operations (warfare)”. Morale is the key ingredient of leadership and the sustainment of morale is integral for commanders on the ground to lead soldiers exposed to extreme conditions and battlefield inoculation environment (Malaysian Army, 2007; United States Marine Corps, 1997; United States Department of Defence, 2010, Australian Army, 2009; Murphy & Farley, 2002; Gal & Manning, 1987; Goyne, 2004; Shamir et al., 2000; Hooker, 1995; Griffith, 2002; Nkewu, 2014).

Morale has been instrumental in productivity and has been promulgated as a three–dimensional factor output as it leads to individual inputs, expectations, interactions, and performance (Smith, 1976). Soldiers often have to sacrifice their moral obligation in putting their mission as the most important temptation for military duties which may arguably even take his life. The definition of morale has arguably been a consistent association of words describing one’s excitement, motivation, and related fundamentals which that individual jives with a group or team. According to Baynes (1987) morale is defined as "the enthusiasm and persistence with which a member of a group engages in the prescribed activities of that group". Manning (1991), defined morale as a function of cohesion and esprit de corps." Whilst Britt (2006) term morale as "a soldier's level of motivation, commitment, and enthusiasm for accomplishing unit mission objective under stressful conditions."

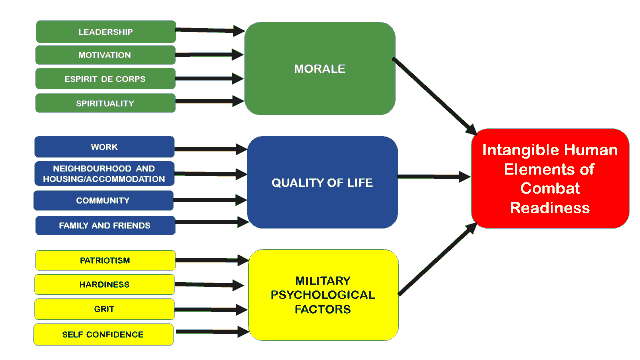

From the literature review on the morale component on intangible elements, this research will take cognizance of various antecedents of morale namely leadership, motivation, esprit de corps, and spirituality. Scholars have agreed that leadership is the ultimate element in sustaining power of morale which is of utmost importance among officers and soldiers who are exposed to various conditions and bombarded in heavy fire scenarios and environment (Malaysian Army, 2007; United States Marine Corps, 1997; United States Department of Defence, 2010, Australian Army, 2009; Murphy & Farley, 2002; Gal & Manning, 1987; Goyne, 2004; Shamir et al., 2000; Hooker, 1995; Griffith, 2002; Nkewu, 2014).

Esprit de Corps is defined as “the winning Spirit within the Army Profession, embedded in our culture, sustained by traditions and customs, fostering cohesive and confident units with the courage to persevere” (Wierzbicki, 2017). The richness of synergy boding within soldiers in their unit will depict their inclination to fight as a team and the fighting generation power (Malaysian Army, 2011; Cushman, 1947; Gal, 1986; Baynes, 1987; Siebold & Manning, 1999; Krulak, 1996). The living standards and infrastructure of the military community living in military camps could improve and enhance the spirit de corps and morale of soldiers (Malaysian Army, 2011). This inducement provides the dimension of community amalgamation and commitment as well as the provision of social support (National Research Council, 2002). These indicators contribute towards their quality of life and the environment of command climate in the unit. (Flanagen, 1978; Bestuzhey-Lada, 1980; Murrell et al., 1983; Glatzer, 1987; Moller, 1992; Rath & Harter, 2010).

Motivation is the indicator of the morale of soldiers who are ready to go for combat duties despite knowing the ultimate results could be deadly. Soldiers must be fully motivated for combat duties to be able to accomplished mission deployment success (Murphy & Fogarty, 2009; Britt, Castrol & Adler, 2006; Siebold & Manning, 1999; Goyne, 2004). Motivation is the element of morale that gives the soldiers the grit and hardiness in going to combat duties whereby invariably risking his life. Soldiers must be fully motivated or else they will not be able to be deployed in any mission (Murphy & Fogarty, 2009; Britt, Castrol & Adler, 2006; Siebold & Manning, 1999; Goyne, 2004).

Spiritually has been defined as “the continuous journey people take to find meaning in their lives” and “the process of searching for the sacred in one’s life” (Pargament & Sweeney, 2011). These definitions capture the personal essence of spirituality and the way it is individually defined by each person. Two consistent findings from the literature are worth emphasizing. Leadership may be defined as directly or indirectly influencing others, employing formal authority or personal attributes, to act following one’s intent or a shared purpose” (Canadian National defence, 2005). According to Bass (1990) leadership is referred to as one of the key aspects in the failure or success factors of an organisation. On the other hand, Yukl (1989) defined leadership as "influencing task objectives and strategies, influencing commitment and compliance in task behaviour to achieve these objectives, influencing the culture of an organization." It means that the conduct and deeds of the subordinates or the followers are influenced by the leader’s behaviour to attain a mutual objective.

Military Psychological Factors

Psycho is defined as “the study of human nature or the mind, its functions and behaviour whilst social refer to society explaining the group of individuals living together with share laws and organizations” Meijer, M., & de Vries, R. (2005). At such the combination of both words articulate how individuals interact and socialise with others around them which in simpler terms relates how humans work in society and their working relationship. Military psychology is defined as “the research, design, and application of psychological theories and empirical data towards understanding, predicting, and countering behaviours in friendly and enemy forces, or in civilian populations” (Isaeva,2020). Military personnel’s like any human being tend to have psychological problems and seeking medical assistance for mental health is compulsive and erroneous since they are supposed to be soldiers (Matthews, 2014). Soldiers tend to avoid medical assistance even if they know they have psychological issues involving mental health (Vogt D,2011), Ego sandwiched with personal and interpersonal variables are correlated to the stigma perception is comforting to mental assistance especially in the military (Corrigan PW,2004). In this aspect research on potential barriers in seeking psychological help can enable military researchers to prepare soldiers pre and post-military combat operational duties. Military personnel’s like any human being tend to have psychological problems and seeking medical assistance for mental health is compulsive and erroneous since they are supposed to be soldiers (Matthews, 2014). Soldiers tend to avoid medical assistance even if they know they have psychological issues involving mental health (Vogt D,2011), Self-esteem sandwiched with personal and interpersonal variables are correlated to the stigma perception is comforting to mental assistance especially in the military (Corrigan PW,2004). Mental toughness is significantly a valuable asset to military personnel than physical toughness (Karamanoli & Stigma, 2015). In this aspect research on potential barriers in seeking psychological help can enable military researchers to prepare soldiers pre and post-military combat operational duties

The skills and aptitude of an individual‘s self-perception have been the hallmark of self-confidence (Wilson et al., 2007). Their self-perception correlates and embarks the individual’s achievement of his intentions and purposes (Kasouf et al., 2015). Skill levels and managerial experience, for example, self-confidence is based on perceptions of skills and abilities (Wilson et al., 2007), rather than actual or objective ability. For military scenario training and indulged preparation replicating combat condition in realistic environment assist in building self-confidence (Warr, Allan, & Birdi, 1999). These are essential factors especially for soldiers ready for combat and military duties in collective and teamwork.

A person with grit sustains endurance in long-term outcomes reflects the way forward orientation which differentiates effective leaders (Ilies et al., 2006; Kouzes and Posner, 2017). Although grit is not related directly to intelligence since it accounts for more variance in the aftermath and long-term consequences but it constitutes thoroughness in some areas of interest (e.g. Duckworth et al., 2007; Tedesqui and Young, 2018). This leads to grit being a predictor of leadership especially in the psychological aspect of soldiers ready for combat duties Midkiff et al., 2017).

Patriotism is identified as an individual’s loyalty to their country, identification with it, and the readiness and compliance to act on its behalf (Kleinig et al., 2015). The long history of patriotism has evolved over many years in its true meanings, and connotations (Cunningham, 1981; Dietz, 2002). The term patriotism is a commonplace that the concept summons endlessness, yet it is not so (Kleinig et al., 2015). There are many variants of patriotism. Unlike loyalty, patriotism can mean the sense of duty and service to the nation, opposition to the government or king in the name of constitutional principles, or even against the centralized nation and capitalism (Cunningham, 1981; Dietz, 2002). Some consider patriotism as a blind image and educating about patriotism is indoctrination. Psychological hardiness has often been associated with many theories and thoughts such as social interest, separation and psychological hardiness (Leak & Williams, 1989), stress and sickness (Klag and Bradley, 2004), workplace stress (Lambert et al., 2003), happiness and life satisfaction, thinking and feeling that your life is going well (Terzi, 2005), creating a happy working environment (Judkins & Furlow, 2003), mental health (Maddi & Khoshaba, 1994), and the distinct personality concept of hardiness (Maddi et al., 2006). Many researchers have concluded that hardiness is a composite construction with a calculated total hardiness score (Durak, 2002; Harrisson et al., 2002; Maddi et al., 1996; Morrisey & Hannah, 1986; Terzi, 2005). Other preceded hardiness as a combination of three constructs namely commitment, control, and challenge (Crowley et al., 2003; Klag & Bradley, 2004; Maddi et al., 2006; Maddi & Khoshaba, 1994).

Quality of Life

Definitions of quality of life have been often depicted interchangeably with other formalities of tangible and non-tangible elements which are subjective concepts such as life satisfaction, well-being, happiness, and good life (Cheng, 1988; Diener, 1984; Rice, 1984). Quality of life concepts depends on the individual and the environment which is conceived in the dimensions of well-being, satisfaction, and standard of living (Campbell et al., 1976). The capability of an individual is often correlated to the quality of that person. Capability is defined as the instinct conations of a person’s ability or potential to do or be something in achieving life various facets of life such as health and education (Sen, 1987). Studies have shown that quality of life is another intangible element of combat power on an individual’s combat readiness indicator. From research on literature review, some of the domains used on the quality of life include financial; housing; health and personal safety; family life; relation with superiors, subordinates, and colleagues; neighborhood community; work environment and career development (Verwayen, 1980; Zapf, 1980; McKennell, 1978).

Quality of life has many dimensions of explanations as we revolve around the tangible and intangible aspects of determining an individual’s quality of life. Some recognize it as a multi-faceted cloud where certain tangible material facets of the hierarchy of wants such as wealth, natural and living environment, material living conditions, economic and physical safety. Some quality of life elements is related to intangible matters such as the overall experience of life, health, education, leisure, and social interactions. Studies have shown that quality of life is another intangible element of combat power on an individual’s combat readiness indicator. From research on literature review, some of the domains used on the quality of life include financial; housing; health and personal safety; family life; relation with superiors, subordinates, and colleagues; neigbourhood community; work environment and career development (Verwayen, 1980; Zapf, 1980; McKennell, 1978). The definition of health by the World Health Organization concludes that the three main elements are physical, mental, and social aspects (WHL, 1995). Quality of Life (QOL) is defined as the “context of individual cultural and subcultural systems associated with personal goals, expectations, standards, and values” (Larson, 1995). World Health Organization has continuously supported the efforts on people to have a productive quality of life preservation of function and well-being and the extension of human lives (WHO, 1995). The transformation of challenges for the mental and physical well-being of soldiers often is associated with varying administrative, characteristic and political portfolios (Martins, 2012). There is a proper investigation on the stressors in the military environment including factors that influence health so that suitable medical intervention can be provided for military personnel. Soldier son military duties need to be mentally and physically prepared at all-time especially when confronted in combat duties. A single soldier's mental health has an impact on the whole unit of military duties. As such the aspect of maintenance of welfare and mental health is correlated with the quality of life elements which all militaries have to be challenged for the well-being inoculation. This relationship is desirable for militaries to ensure the maintenance of the welfare of soldiers and troop strength. Quality of Work-life improvements is defined “as any activity which takes place at every level of an organization which seeks greater organizational effectiveness through the enhancement of human dignity and growth” (Shefali, 2014). The determination of all stakeholders in the organization, management, and employees to work together so that appropriate changes of work-life are identified for actions and improvements to achieve the quality of life at work for all members of the organization. This will create effectiveness for both the employees and the organization.

The essence of quality work life will portray an atmosphere of cohesive and highly motivated employees who will strive for improvement and work improvements. Although monetary gains are the most important aspects of working life, nevertheless the cost of elements like physical working conditions, job restructuring, and job re-designing, career development, promotional opportunities, etc. are gaining importance rapidly (Shefali, 2014). Employees will focus on individual and collective work development which will insinuate overall working performance in any organization (Walton, 1975).

Research on work quality related to the quality of life concludes that working environment are the main elements towards the quality of life which has an impact on combat readiness (Campbell, 1976; Andrews & Withey, 1976; Flanagen, 1978; Bestuzhey-Lada, 1980; Murrell et al., 1983; Glatzer, 1987; Rath & Harter, 2010). Soldiers are motivated to improve work efficiency in military duties as part of their working environment which instills discipline, mental and physical ability in their workplace (Rath & Harter, 2010). Quality of life encompasses the infrastructure of accommodation and neighborhood friends which enlightens their social environment (Sirgy & Cornwell, 2002). The driving force on the functioning of society is related to infrastructure (Roelich et al., 2015). Social infrastructure provides the push factor and is associated with social resources (Grum & Temeljotov Salaj, 2013). The social dimension provides the pillars of sustainability (Sierra et al., 2018a, 2018b). The need for social infrastructure is essential to correspond one life well-being towards the quality of life. Elements such as friendly and safe neighbourhoods including social dominants such as close friends and family-oriented pleasure provide the fundamental structure of quality of life (Pogrebskyi, 2016).

The presence of work-family conflict increased work turnover and generates increased sickness (Hacker & Doolen, 2003). Alternately this has led to a decrease in work output and leading to poor families, community interactions, and quality of life satisfaction (Hassan, Dollard & Winefield, 2010). There is a need for integration and a combination of a sustainable environment and improvement of services and social environment. The commitment towards family and friends among soldiers and their families indicates morale and quality of life dimension (Hacker & Doolen, 2003).

According to Ru?evi?ius, 2012, the domains of quality life include the material state in welfare, living conditions, economics quality; average income, purchasing power, work and recreation conditions, etc. Another aspect mentioned about the quality of life encompasses the community, social relationship with friends and neighbours. Infrastructure in accommodation and neighbours provide the pillars of motivation for soldiers (Campbell, 1976; Andrews & Withey, 1976; Bestuzhey-Lada, 1980; Murrell et al., 1983; Verwayen, 1980; Glatzer, 1987; Moller, 1992; Rath & Harter, 2010).

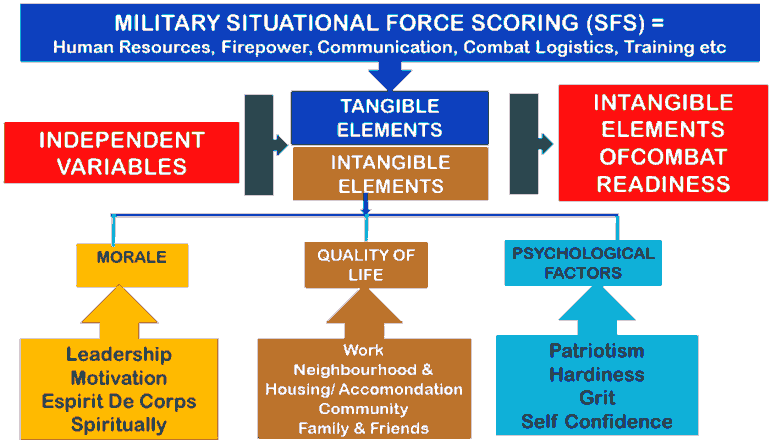

Significance and Research Methodology

This research will be conducted in most operational military bases after applying and soliciting approval from the various Royal Malaysian Navy and Royal Malaysian Air Force Headquarters. Their agreement and support are essential to the cooperation from commanding officers of targeted military units and respondents located in operational areas. An exploratory study was conducted to engage the top military commanders in various Headquarters and units including soldiers from various ranks on the ground. The purpose of the preview was to gauge the current situational awareness of individuals on the intangible human factors which will be the centre piece of this research. Various focus group sessions and interviews were conducted to ascertain these fact-finding elements to focus on key intangible combat readiness domain to integrate into this research. The various variables of previous studies and research will be used as a guide in formulating questionnaires for data collection and analyses. A meta-analysis of research on operational and combat readiness formulation of a systematic framework assessment tool and model for operational readiness for the Malaysian Armed Forces will be conducted by mixed-method both quantitative and qualitative. as shows in Figure 3.

For this research, the variables have been determined from previous past research and also from previews on the ground with top management and soldiers. The framework for this research will only include the intangible human dimension factors which are indicated as intangible combat readiness factors. This includes morale, quality of life, and military psychological factors. The concept for combat readiness is showed in Figure 3 which shows the hybrid combination of tangible and intangibles elements equating to combat readiness. But for this research, only the intangibles factors in morale, quality of life, and psychological factors will be used to establish an instrument for measuring the intangible combat readiness equation. as shows in Figure 4.

A meta-analysis of research on current operational and combat readiness of the Malaysian Armed Forces based on current doctrines and interviews with current top management of the Malaysian Armed Forces. Using past research on other major militaries of the world such as the US Army, Australian Army, Canadian Army to understand the current concept of operational and combat readiness assessment framework and model to determine the best approach and practices currently employed by them. Retrospective Interview protocols with soldiers on combat duties in the field to determine what variables and factors are evident for combat readiness assessment framework and model to be used in the Malaysian Armed Forces in the future based on current environment, situational awareness, and military technologies. Questionnaires were designed to determine the various variables and factors to determine the combat readiness assessment framework and model with approaches towards operational readiness for deployment and combat duties for the military preparedness. Focus group interviews were conducted with selected Senior and Junior Military Officers, Senior Non Commissioned Officers (SNCOs) and Junior Non Commissioned Officers (JNCOs) including the Chief of Defence Force.

Conclusion

Different militaries globally have always concluded the different perspectives of understanding and theoretically defining combat readiness. This realistically is subjected to their military doctrine, policies, and public communications in the preparedness of their military forces for combat duties. Combat readiness is essential for all militaries for preparing the manpower, combat logistics, and the readiness of the soldier’s preparedness for combat and operational duties. Different militaries globally have always concluded the different perspectives of understanding and theoretically defining combat readiness. The intangible elements dictated in this research will refer to past researches and the preview of interviewing with top military officers and soldiers on the ground especially in operational areas to ascertain the human intangible elements which provide the complete equation in the combat readiness formulae. This research will provide in-depth dimensions on the morale, quality of life, and military psychological factors which attribute to the intangible human elements of combat readiness. This research is significant as it provides the Malaysian Armed Forces the measurement tool to provide preventive and corrective measures based on their individual and collective team scores before undergoing operational or combat duties.

Acknowledgement

We wish to record our gratitude to the National Defence University of Malaysia in particular to the Centre of Research and Innovation for supporting and consenting us to do this research. The Ministry of Education (MOE) has funded this study under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2019/SS03/UPNM/02/2) to complete this research. Also our gratitude to the Malaysian Armed Forces for allowing us to conduct this research in their military bases throughout Malaysia. My sincere thanks to my co-authors for mentoring and supporting me in writing this article.

References

- Andrews, F.M., & Withey, S.B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: The development and measurement of perceptual indicators. New York: Plenum.

- Andrews, R.P., & Shambo, J.F. (1980). A system dynamics analysis of the factors affecting combat readiness (Unpublished Master"s thesis). Air Force Institute of Technology, Ohio. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a089364.pdf.

- Allen, P., & Barry, W. (1987). Secondary Land theater Model, RAND, N-2625-NA.

- Baynes, J. (1987). Morale: A study of men and courage. Washington DC: Avery Pub Group. In the U.S. Army study of the human dimension in the future 2015-2024.

- Bestuzhey-Lada, I.V. (1980). Way of life related concepts as parts of a system of social indicators. The quality of life: Comparative studies. London: Sage Publications

- Bester, P.C., & Stanz, J.K. (2007). The conceptualization and measurement of combat readiness for peace support operations- an exploratory study. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 33(3), 68-78.

- Betts, R.K. (1995). Military readiness: Concept, choices, consequences. Washington DC: Brookings Inst Pr. Retrieved from http://trove.nla.gov.au /work/31624781?q&version Id=38339409.

- Blishen, B., & Atkinson, T. (1980). Anglophone and Francophone Differences in Perception of the Quality of Life in Canada. London: Sage Publications. Retrieved from http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/ 10038628?q&versionId=11661889.

- Both, P.E.G. (1984): Operational Readiness in the Royal Netherlands Navy (In Dutch). Den Helder: Royal Netherlands Naval College.

- Britt, T., Castrol, A., & Adler, A. (2006). Military Life: The Psychology of Serving in Peace and Combat, Military Performance.

- Brown, C.W., & Moskos C.C. (1976). The American volunteer soldier: Will he fight? Military Review. Retrieved from http://160.149.101.23/ milrev/english/janfeb97/browncw.htm.

- Campbell, A., Converse P.E & Rodgers, W. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations and satisfactions. New York, Russell Sage Foundation.

- Campbell, A. (1976). Subjective measures of well-being. American Psychologist, 31, 117-124.

- Campbell, A., Converse P.E & Rodgers, W. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations and satisfactions. New York, Russell Sage Foundation.

- Corrigan, P.W. (2004). Target-specific stigma change: A strategy for impacting mental illness Stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28(2), 113-121.

- Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Corrigan, P.W. (2004). Target specific stigma change: A strategy for impacting mental illness stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28(2), 113-121.

- Cochrane, M. (2017). The politicization of climate change and the united states department of defense. University Honors Theses.

- Corrigan, P.W. (2004). Target-Specific Stigma Change: A Strategy for Impacting Mental Illness Stigma, Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2004; 28 (2): 113–121.

- Crowley, B.J., Hayslip, B., & Hobdy, J. (2003). Psychological hardiness and adjustment to life events in adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 10(4), 237-248.

- Cunningham, H. (1981). The language of patriotism, 1750-1914.

- Cushman, R.E. (1947). Battle Replacements. Marine Corps Gazette, 46-50.

- Clausewitz, C.V. (1874). On nature of war. Trans. and ed. J. Graham. London: Penguin Group, p.51. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1946/1946-h/1946-h.html

- Dawne, V. (2011). Mental health-related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: A review. The American Psychiatric Association, 62(2), 135-142.

- Defence White Paper (2020). A Secure, Sovereign and Prosperous Malaysia. Ministry of Defence Defence White Paper ISBN 978-967-16437-6-1 1.

- Dietz, M.G. (2002). Patriotism: a brief history of the term, in Primoratz, I. (Ed.), Patriotism, Humanity Books, New York, NY.

- Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D., & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 1087-1101.

- Durak, M. (2002). Predictive role of hardiness on psychological symptomatology of university students experienced earthquake. The Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

- Flanagen, J.C. (1978). A research approach to improving our quality of life. American Psychologist, 33, 138-147.

- Filjak, T., & Denacic, D. (2005). Terrorism fighting readiness – Related to “classic” psychological combat readiness in the Croatian Armed Forces.

- Fils, J.F. (2006). The measurement of morale among Belgian military personnel deployed in crisis operations: A longitudinal survey design. In Human Dimensions in military operations – Military leaders’ strategies for addressing stress and psychological support (pp.28-1, 28-8) Meeting Proceedings RTO-MP-HFM-134-134, Paper 28. Neuilly-sur-Seine, France: RTO. Retrieved from http://www.rto.nato.int/abstracts.asp.

- Fils, J.F. (2006). The measurement of morale among Belgian military personnel deployed in crisis operations: A longitudinal survey design. In Human Dimensions in military operations – Military leaders’ strategies for addressing stress and psychological support (pp.28-1, 28-8) Meeting Proceedings RTO-MP-HFM-134-134, Paper 28. Neuilly-sur-Seine, France: RTO. Retrieved from http://www.rto.nato.int/abstracts.asp.

- Gal, R. (1986).Unit morale: From a theoretical puzzle to an empirical illustration - An Israeli example. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 16(6), 549-564.

- Gal, R., & Manning, F. (1987). Morale and its components: A cross national comparison. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 369-391.

- Goyne, A. (2004). Measuring unit effectiveness: What do commanders want to know and why? Psychology Research and Technology Group, Australian Army.

- Glatzer, W. (1987). Components of well-being. In A.C. Michalos (ed.), German social report: Living conditions and subjective well-being, 1978-1984.

- Griffith, J. (2002). Multi-level analysis of cohesion's relation to stress, well-being, identification, disintegration, and perceived combat readiness. Military Psychology, 14(3), 217-239. Gal, R. (1986).Unit morale: From a theoretical puzzle to an empirical illustration - An Israeli example. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 16(6), 549-564.

- Griffith, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis of cohesion's relation to stress, well-being, identification, disintegration, and perceived combat readiness. Military Psychology, 14(3), 217-239.

- Gal, R., & Manning, F. (1987). Morale and its components: A cross national comparison. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 369-391.

- Goyne, A. (2004). Measuring unit effectiveness: What do commanders want to know and why? Psychology Research and Technology Group, Australian Army. Retrieved from http://www.internationalmta.org/ Documents/2006/2006011P.pdf.

- Greene-Shortridge, T.M., Britt, T.W., & Castro, C.A. (2007). The stigma of mental health problems in the military. Mil Med, 172, 157-161.

- Griffith, S. (1971). Sun Tzu: The art of war. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Griffith, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis of cohesion's relation to stress, well-being, identification, disintegration, and perceived combat readiness. Military Psychology, 14(3), 217-239.

- Hacker, S.K., & Doolen, T.L., (2003). Strategies for living: Moving from the balance paradigm. Career Development International, 8, 283-290.

- Hair, J.F., Wolfinbarger Celsi, M.A., Money, H., Samouel, P. & Page, M.J. (2011). Essentials of business research methods.

- Armonk, New York: Sharpe.

- Hassan, Z., Dollard, M.F., & Winefield, A.H. (2010). Work-family conflict in East vs Western countries. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 17(1), 30-49.

- Harrisson, M., Loiselle, C.G., Duquette, A., & Semenic, S.E. (2002). Hardiness, work support and psychological distress among nursing assistants and registered nurses in Quebec. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 38(6), 584-591.

- Hoge, C.W., Casiro, C.A., & Messer, S.C. (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 13-22.

- Hooker, R.D. (1998). Building unbreakable units. Retrieved from http://www.usafa.af.mil/jscope/JSCOPE98/HOOK98.HTM.

- Inderjit, S.A., & Norshima, Z.S. (2014). The synchronization of human dimension factors in determining military command climate. European Journal of Educational Sciences, 1(3).

- Ilies, R., Judge, T., & Wagner, D. (2006). Making sense of motivational leadership: the trail from transformational leaders to motivated followers. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13(1), 1-22.

- Isaeva, M.R. (2020). Military psychology and its importance. European Journal of Research and Reflection in Educational Sciences, 8(3).

- Johnston, B.F., Brown, K.J., Cole, A.K., & Agrawal, S. (2002). Measuring organizational climate in the Canadian Forces (Unpublished manuscript). Retrieved from http://www.internationalmta.org/.

- James, H.G. (2020). The fundamentals of military readiness. Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46559.

- Judkins, S., & Furlow, L. (2003). Creating a hardy work environment: can organizational policies help? Texas Journal of Rural Health, 21(4), 11-17.

- Karamanoli, V. (2015). Stigma and attitudes toward mental help seeking: the example of the military environment. Psychology, 21(2).

- Kasouf, C.J., Morrish, S.C., & Miles, M.P. (2015). The moderating role of explanatory style between experience and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 1-17.

- Kleinig, J., Keller, S., & Primoratz, I. (2015). The ethics of Patriotism: A Debate, Wiley Blackwell, West Sussex.

- Klag, S., & Bradley, G. (2004). The role of hardiness in stress and illness: an exploration of the effect of negative affectivity and gender. British Journal of Health Psychology, 9, 137-61.

- Kirkland, F.R., Bartone, R.T. & Marlowe, D.H. (1993). Commander’s priorities and psychological readiness. Armed Forces & Society, 19(4), 579-598.

- Kouzes, J.M., & Posner, B.Z. (2017). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations, 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: The Leadership Challenge – A Wiley Brand.

- Kwong, F.W. (2015). Integrative model of the tangible and intangible elements of combat power for the Malaysian Army combat readiness. National Defence University of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Kwong, F.W., Norazman, M.N., & Jegak, U. (2017). An integrative model for measuring combat readiness. International Journal of Advanced Research, 5(7), 1449-1462.

- Leak, G.K., & Williams, D.E. (1989). Relationship between social interest, alienation, and psychological hardiness. Individual Psychology, 45(3), 369-375.

- Lambert, C.E., & Lambert, V.A. (1999). Psychological hardiness: State of the science. Holistic Nursing Practice, 13(3), 11-19.

- Lambert, V.A., Lambert, C.E., & Yamase, H. (2003). Psychological hardiness, workplace stress and related stress reduction strategies. Nursing and Health Sciences, 5, 181-184.

- Likert, R. (1967). The human organization. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Maddi, S.R., Harvey, R.H., Khoshaba, D.M., Lu, J.L., Persico, M., & Brow, M. (2006). The personality construct of hardiness III: relationships with repression, innovativeness, authoritarianism, and performance. Journal of Personality, 74(2), 575-98.

- Malaysian National Defence Policy (2014). Malaysian defense policy.

- Malaysian Army (2019). United Nations reporting operations and training headquarters.

- Malaysian Army (2007). Command, leadership and management. Kuala Lumpur: Central Ordnance Depot.

- Malaysian Army (2011). Malaysian army transformational plan. Kuala Lumpur: Central Ordnance Depot.

- Matthews, M.D. (2014). Head strong: How psychology is revolutionizing war. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Manning, F.J. (1991). Morale cohesion and esprit de corps. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Maj, R.D. (2006). Whole soldier performance: A value-focused model of soldier quality, USMA Department of Systems Engineering: West Point, NY.

- MacDonough, T.S. (1991). Noncombat stress in soldiers: How it is manifested, how to measure it and how to cope with it. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- McKennell, A.C. (1978). Cognition and affect in perceptions of well-being. Social Indicators Research, 5, 389-426.

- Manning, F.J. (1991). Morale Cohesion and esprit de corps. In R. Gal & A.D. Mangelsdorff (Eds), Handbook of Military Psychology. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Martins, L.C., & Lopes, C.S. (2012). Military hierarchy, job stress, and mental health in peace time. Occupational Medicine, 62(3), 182-187.

- Meijer, M. (1998): Personnel flows in organizations. Assessing the effects of job rotation on organizational output (In Dutch). Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

- Murphy, P.J., & Farley, K.M.J. (2002). Morale, cohesion and confidence in leadership: Unit climate dimensions for Canadian soldiers on operations. The human in command: Exploring the modern military experience. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Murphy, P.J., & Farley, K.M.J. (2000). Morale, cohesion, and confidence in leadership: Unit climate dimensions for Canadian soldiers on operations.

- Murphy, P.J., & Fogarty, G. (2009). The human dimensions of mission readiness. In Focus on human dimensions in land operations. Canberra: Department of Defence.

- Mumford, S.J. (1976). Human resource management and operational readiness as measured by refresher training on navy ships. San Diego: Navy Personnel Research and Development Center. Retrieved from www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA022372.

- Murphy, P.J., & Farley, K.M.J. (2002). Morale, cohesion and confidence in leadership: Unit climate dimensions for Canadian Soldiers on operations. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. Retrieved from http://www.springer.com/psychology/book/978-0-306-46366-2.

- Maddi, S.R., & Khoshaba, D.M. (1994). Hardiness and mental health. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63(2), 265-74.

- Moller, V. (1992). Applications of subjective well-being: Measures in quality of life surveys (Centre for Social and Development Studies CSDS Working Paper No. 5). Durban: University of Natal Durban.

- Midkiff, B., Langer, M., Demetriou, C. & Panter, A.T. (2017). Measuring grit among first-generation college students: a psychometric analysis. Quantitative Psychology, Springer International Publishing, New York, NY.

- Morrisey, C., & Hannah, T.E. (1986). Measurement of psychological hardiness in adolescents. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 148(3), 393-397.

- Murrell, S.A., Schulte, P.J., Hutchins, G.L. & Brockway, J.M. (1983). Quality of life and patterns of unmet need for resource decisions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11, 25-39.

- Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory. New York: Mac-Graw Hill. Retrieved from http://psychology.concordia.ca/fac/kline/library/k99.pdf.

- Nkewu, Z. (2014). Impact of psychological wellbeing and perceived combat readiness on willingness to deploy in the SANDF: An exploratory study (unpublished Master dissertation). Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (2013). North Atlantic Treaty Organization NATO. International Organizations, 2013.

- Patrick, A. (1992). Situational force scoring: Accounting for combined arms effects in aggregate combat models.

- Pargament, K.I., & Sweeney, P.J. (2011). Building spiritual fitness in the Army: An innovative approach to a vital aspect of human development. American Psychologist, 66, 58-64.

- Rath, T., & Harter, J. (2010). Well Being: The five essential elements. New York: Gallup Press.

- Robert, A., Dees, S.T., & Nestler, R.K. (2013). Whole soldier performance appraisal to support mentoring and personnel decisions. Retrieved from 10.1287/deca.1120.0263..

- Richardson, F.M. (1978). Fighting spirit: A study of psychological factors in war. London: Leo Cooper.

- Richard, B. (1995). Military readiness: Concepts, choices, and consequences. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Riley, M.A. (2002). Measuring the human dimension of unit effectiveness – the Unit Morale Profile. 38th International Applied Military Psychology Symposium, Amsterdam: The Netherlands.

- Rosenberger, J.D. (1999). Reversing the Downward Spiral of Combat Readiness: Change the way we measure it. Military Review, 79(6), 54.

- Ru?evicius, J. (2012). Quality management. Global concept and research in the field. Vilnius: Akademine leidyba Publishing House.

- Schumm, W.R., Bell, D.B., Rice, R.E. & Schuman, P.M., (1996). Marriage trends in US Army. Psychological Reports, 78, 771-784.

- Shamir, B., Brainin, E., Zakay, E., & Popper, M. (2000). Perceived combat readiness as collective efficacy: Individual- and group-level analysis. Military Psychology, 12(2), 105-119.

- Shefali, S., & Rooma, K. (2014). Study on quality of work life: Key elements & its implications. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 16(3), 54-59.

- Siebold, G.L., & Manning, F.J. (1999). The evolution of the measurement of cohesion. Military Psychology, 11(1), 21-22.

- Summers, H. (1998). Military and C4i, Retrieved from http://www.infowar.com/mil_c4i/mil050298c_j.s.html.

- Tedesqui, R.A., & Young, B.W. (2018). Comparing the contribution of conscientiousness, self-control, and grit to key criteria of sport expertise development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 34, 110-118.

- Terzi, S. (2005). A psychological hardiness model for subjective well-being. Gazi University, Ankara.

- The North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Libya: reviewing Operation Unified Protector (2013). http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/download.cfm?q=1161 External.Library of Congress Control Number 2013412420.

- The conceptualisation and measurement of combat readiness for peace-support operations: An exploratory study (1997). Ministry of public works and government services of Canada.

- The WHOQOL Group (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science & Medicine, 41(10), 1403-1409.

- United States Department of Defence (2010). CJSC guide to the chairman’s readiness system. United States of America: Joint Chief of Staff. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/cjcs_directives.

- van Dyk, G.A.J. (2015). Managing morale on the battlefield: A psychological perspective. Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, 43(1), 128.

- Voith, M.R. (2001). Military Readiness. The Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin, 4(2).

- Verwayen, H. (1980). The specification and measurement of the quality of life in OECD countries. London: Sage.

- Warr, P., Allan, C., & Birdi, K. (1999). Predicting three levels of training outcome. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 351-375.

- Warr, P., Allan, C., and Birdi, K. (1999). Predicting Three Levels of Training Outcome. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 351-375.

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31(3), 387-406.

- Wolosin, D.G., Wilcove, G.L., & Schwerin, M.J. (2003). An exploratory Model of Quality of Life in the U.S. Navy. Millington, Tennessee: Navy Personnel Research Studies and Technology. Military Psychology, 15(2), 133-152.

- Xue, C., Ge, Y., Tang, B., Liu, Y., & Kang, P. (20 March 2015). A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related ptsd among military personnel and veterans. PLOS ONE. 10(3), e0120270.

- Yurechko, J.J. (2007).The soviet combat readiness system, London: Routledge.

- Yurechko, JJ. (2007). The Soviet combat readiness system, London: Routledge. The Journal of Soviet Military Studies, 231-242.

- Zapf, W. (1980). The SPES social indicators system in comparative perspective. In A. Szalai & F.M. Andrews (Eds.), The Quality of Life: Comparative Studies (pp. 249-269). London: Sage Publications. Retrieved from http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/10038628?q&versionId.