Research Article: 2024 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

Marketing fair trade products to a student audience: The Portuguese case

Francisco Fernando Ribeiro Ramos, Coimbra Business School, Coimbra, Portugal

Citation Information: Ramos, F. F. R. (2024). Marketing Fair Trade Products To A Student Audience: The Portuguese Case. Journal of International Business Research, 23(4), 1-28.

Abstract

Over the last decade, sales of fair trade products have grown consistently in most European countries, but this has not happened in Portugal. A limited number of previous studies allow us to conclude that there is a potential market seeking fair trade products but fair trade organizations have been unable to explore this market. This research project has been undertaken in Portugal to understand how to market fair trade products to a student audience. To our knowledge, neither the previous four studies research this particular group of consumers. Our research aims to discuss the two following questions: (1) Do students actually purchase fair trade goods and why? (2) How can marketing be effective to increase sales of such products among this consumer group? Accordingly, the three research objectives are: 1) To gain an insight into the perception of the fair trade concept and products held by a student audience ranging from 17 to 30 years old. We first evaluate the level of awareness and understanding of the concept. We then explore their attitudes to fair trade products. 2) To identify differences between intent and actual student purchase behaviour for fair trade products and the drivers them. 3) To formulate recommendations which reach this specific group of consumers. The paper is organised into four main sections. It begins with an overview of existing literature considering the development of fair trade, and then detailing the profile of the typical consumer and the drivers behind the ‘ethical purchase gap’. Thereafter, it provides an explanation on the research methodology, and presents the findings from questionnaires, focus groups and interviews. Following on from this, a discussion with a series of marketing recommendations takes place.

Key words

Consumer Behavior; Fair Trade Products; Marketing; Portuguese Students.

Introduction

This research project has been undertaken in Portugal to understand how to market fair trade products to a student audience. A review of existing definitions by Jones et al., (2003) finds that there is no definitive or legal meaning of fair trade, but all have broadly common themes. Moreover, it is important to see a clear distinction between ‘ethical trade’, which is a matter a corporate policy, and ‘fair trade’, which is product specific and developmentally focused (Nicholls, 2002).

In simple terms, fair trade is an alternative approach to trading partnership that aims to achieve the sustainable development of disadvantaged producers in the Third World (Strong, 1997; Nicholls, 2002). It means, “The buying of products from producers in developing countries on terms that are more favourable than free-market terms, and the marketing of those products in developed countries at an ‘ethical price premium’. This premium, borne by the consumer, allows producers to receive a fairer price for their products” (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005a:515). Accordingly, fair trade is defined by several key practices and cultural contexts (Al-Khatib et al., 1997), (Nicholls, 2002):

• Direct purchasing from producers;

• Transparent and long-term trading partnerships;

• Co-operation not competition;

• Agreed minimum prices, usually set ahead of market minimums;

• Focus on development and technical assistance via the payment to suppliers of an agreed social premium (often 10 per cent of the cost price of goods); and

• Provision of market information to producers.

The impressive growth of fair trade sales has been one of the most notable retail phenomena of the past ten-twenty years (Nicholls and Opal, 2005; Dragusannu et al., 2014). Worldwide consumers spent over £9.6 billion on certified products in 2019 (Fairtrade Foundation, 2020). This corresponds to a 27% increase on the previous year and means that over 14 million people in 68 developing countries – 2.8 million farmers, workers and their families – now benefit from fair trade sales. The UK represents the second biggest market in the world, before Switzerland and behind the USA.

Data from EFTA (European Fair Trade Association) reveals that total sales of Fair Trade products has been increasing steadily every year. Total Fair Trade retail value of EFTA’s members climbed from € 147,539,668 in 2001 to € 491,510,063 in the year 2009 and € 985,156, 252 in 2019. This corresponds to an increase of 200% in Fair Trade sales in Europe over the 10-year period or an average of 7,2% growth per year.

Consumers appear to demonstrate an increasing interest in the goods they consume, typically looking for more information concerning provenance and background. Such interest includes a more general move towards ethical consumption, allowing “consumers to express their feelings of responsibility towards society and their appreciation of ethical companies and products” (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005a:516). However, there is an observable difference “between those consumers who identify themselves as purchasers of ethical products and, therefore, likely supporters of Fair Trade, and the market share of many Fair Trade products”, typically accounting for one – three per cent (Nicholls & Lee, 2006:370).

Several researches have acknowledged this ‘ethical purchase gap’ and the drivers behind it (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Nicholls, 2002; De Pelsmacker et al., 2005b; Nicholls & Opal, 2005; Nicholls & Lee, 2006, D’Astous & Mathieu, 2008; Johnstone & Tan, 2015; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018; Kossmann & Gomez- Suarez, 2019). Yet, variations in time, research objectives, methodology, sample size and demographics may explain why dissimilar findings have been found. Meanwhile, there has been no research to date, that has specifically addressed students as consumers despite the fact they represent both a current and an influential future market. Indeed, while students are already consumers for themselves, they will become the purchasers for their households in the next ten or fifteen years. If students have a positive attitude about fair trade issues and such products correspond to an everyday purchase, they are likely to have a considerable impact in the future success of fair trade (Nicholls & Opal, 2005; Nicholls & Lee, 2006).

Taking into account this considerable stake, the present research aims to discuss the two following questions:

• Do students actually purchase fair trade goods and why?

• How can marketing be effective to increase sales of such products among this consumer group? Accordingly, the three research objectives are:

• To gain an insight into the perception of the fair trade concept and products held by a student audience ranging from 17 to 30 years old. We first evaluate the level of awareness and understanding of the concept. We then explore their attitudes to fair trade products.

• To identify differences between intent and actual student purchase behaviour for fair trade products and the drivers them.

• To formulate recommendations to reach this specific consumer group. If marketers understand the nature of the ethical purchase gap, they may be able to close it. It is both an exciting and challenging objective because Cowe and Williams (2000; cited by Nicholls and Opal, 2005) suggested that young people, and thus most students, are not a promising segment because ethical issues are secondary to brand. A recent research by Robichaud and Yu (2021) found a significant influence of knowledge of fair trade towards product interest, in particular, general attitudes towards fair trade had a significant influence on product interest, product likeability and convenience.

An additional objective is to propose enlightenment of the fair trade concept and of its development in Portugal. To our best knowledge, only a few studies have been undertaken in Portugal (Cantista & Rodrigues, 2010; Marques, 2011; Almeida, 2012 & Coelho, 2015) and neither of them researches this particular group of consumers. This study adds to academic knowledge and insights into consumer attitudes and behaviour, with respect to fair trade products. Fair trade organisations may benefit from the findings if they aspire to target a student audience.

This research paper is structured into four main sections. It begins with an overview of existing literature considering the development of fair trade, and then detailing the profile of the typical consumer and the drivers behind the ‘ethical purchase gap’. Thereafter, it provides an explanation on the research methodology, and presents the findings from questionnaires, focus groups and interviews. Following on from this, a discussion with a series of marketing recommendations takes place.

Literature Review

Three main areas divide this literature review. The first area outlines the role of marketing in the development of fair trade in Portugal and ultimately explores the drivers behind its expansion. The second area determines the profiles of the ethical and fair trade consumer. The last part scrutinizes the existing published research on purchase decision-making and the ethical purchase gap.

The Market for Fair Trade Products

Why does Fair Trade Exist?

Fair Trade attempts to address the gross imbalances in information and power that typify North-South supplier-buyer relationships, by countering the current failures evident in many global markets. According to Nicholls and Opal (2005) and Dragusannu et al. (2014), macroeconomic (e.g., high levels of debt cause countries to rely on export-intensive industries, export earnings concentrated in primary commodities, failure to distribute export income equitably, etc.) and above all microeconomic conditions (e.g., lack of market access, imperfect information, lack of access to financial markets and credit, inability to switch to other sources of income, weak legal systems, etc.) explain the failure of trade liberalisation to distribute wealth evenly. Taking this into consideration, the two authors assume that the principles of fair trade, by providing a profitable relationship to all those in the supply chain – producers, exporters, importers, manufacturers, and retailers – represent a sustainable market- based solution to correct these global trade failures.

The Development of Fair Trade and the Contribution of Marketing

Historically, Nicholls (2002) has identified that the commercial growth of the fair trade market in Europe, can be seen as developing in four waves. The movement has its origins in the alternative/charity trade initiatives of the 1950s and in a host of small, independent traders. It is linked to a long tradition of alternative philosophical and practical approaches to production and consumption often based on communalism and ‘counter-culture’ (Low & Davenport, 2005). Oxfam in the UK, for example, was initially formed in 1942 as a campaigning organisation dedicated to finding lasting solutions to poverty and suffering around the world. Its charity shop operations date from 1948.

During the 1970s, alternative trading organisations (ATOs) like Tradecraft, established in 1979, emerged with the aim of offering south-based producers the opportunity to trade with the developed world without the control of intermediaries (Nicholls and Opal, 2005; Dragusannu et al., 2014)). ATOs pioneered a move away from “goodwill/solidarity” selling relationships towards more market-driven partnerships. Products were sold mostly through alternative networks of distribution (e.g. catalogues, church organisations, student and political groups, world shops, etc.) to the primary target market of fair trade, including: members of faith-based organisations, leftist political groups and groups committed to “Third World” justice (Low & Davenport, 2005).

The third wave started from the early 1990s. ATOs offered supply chain information to the consumer, launched more mainstream product categories and began to establish nationwide brands like “Cafédirect” in 1991 (Nicholls & Opal, 2005). The main marketing objective was raising issue-awareness with the ‘strongly ethical’ consumers.

In addition, the development of the fair trade certification mark has created trustworthy and more identifiable products. The marketing objective here was building trust in the authenticity of process (Nicholls, 2002). That has provided the opportunity to introduce fair trade products to a mass market via mainstream retailers, such as the Co-Operative Group in 1992, which have seen in support of fair trade the possibility to increase their standing with customers and to enhance their public profiles (Wright & Heaton, 2006).

Solidifying growth in the mainstream has characterised the fourth wave of fair trade development in the UK (Nicholls & Opal, 2005). Marketers have adopted a new approach to enter the market beyond the ‘ethical consumers’ segment, which only represents about five per cent of the population. There have been four marketing objectives driving this change of strategy (Nicholls; 2002):

• To reposition products on quality and differentiation;

• To focus new product development on consumer and producer demands;

• To broaden the message of fair trade to include lifestyle characteristics; and,

• To increase availability of products into national retailers.

The results have been a communication focused on traditional product features (e.g. quality, taste); the market entry of more familiar companies (e.g. Costa Coffee, Starbucks) and the emergence of supermarket own-label products in the vein of the Co- operative Group since 2001.

The Drivers of Success

Nicholls (2002) argues that the growth in consumers’ enthusiasm for fair trade products in the UK is being driven by the interaction of a number of political, academic, cultural and informational influences creating a “general shift in opinion towards the recognition of the value of fair trade in the developed world” (Nicholls, 2002:8).

Politically, Nicholls (2002) claims that the work of pressure groups, charities and campaigners (like Oxfam & Christian Aid) have increased public awareness and media interest of ethical trading issues and have encouraged retailers to support fair- trade products. Moreover, the growing international consensus that ‘trade not aid’ is the best way to alleviate poverty has redefined the political climate for trade with developing countries (Strong, 1996). The exploration of the phenomenon by academic researchers and the proliferation of business ethics courses (as new managers become more sensitive to ethical issues and thus influence corporate behaviour) have also supported the growth of ethical consumerism.

Culturally, it is seen that consumers have a clearer focus on ethical values and that more and more consumers are not only interested with the intrinsic properties of a product, but also on the production and supply chain issues (Jones et al., 2003). The main driver of this cultural shift has been the growth on the amount of easily accessible information about global social issues, accompanied by an increase in media engagement, Internet forums and activities from not-for-profit organisations. The result of this greater consumer interest has been a considerable rising demand for fair trade products and a larger range to satisfy this.

In other words, the growth of ethical consumerism over the last thirty years and the mass-market associated with it provide the main driver behind the development of the fair trade market in the UK (Strong, 1996, 1997; Nicholls, 2002). The marketing literature has commonly used the terms “green consumer”, “ethical consumer” and “voluntary simplicity” as typologies for consumers concerned by ethical issues (Connolly & Shaw, 2006). The study of the ethical consumers, and how the fair trade consumers fits within this larger grouping (Nicholls & Opal; 2005), thus forms the second section of the literature review.

The Ethical and Fair Trade Customers: Between Myth and Reality

According to Nicholls and Opal (2005), and Dragusannu et al. (2014), the strategic questions for the fair trade movement are: (1) when choosing products, who are the people influenced by ethical considerations (2) how can they be segmented to generate future growth opportunities. There is currently a limited amount of research on the profile of the typical fair trade consumer. At first, the study of the ethical consumer therefore represents a smarter approach.

Who are The Ethical Consumers?

Ethical consumers support one of the four ethical themes suggested by Cowe and Williams (2000; cited by Nicholls and Opal, 2005): ethical banking, responsible tourism, recyclable or “green” goods and developmental aid/poverty reduction through fair trade. Several surveys (e.g., Freestone & McGoldrick, 2008) have tried to identify socially responsible or ethical consumers in terms of their demographic characteristics. While some of them deduced that demographics are not significant to define the ethical consumer (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005a, 2006); others studies concluded that the ethical consumer is a person with a relatively high income, education and social status.

Furthermore, Cowe and Williams (2000; cited by Nicholls & Opal, 2005) explored the profile of the ethical consumer through research that combined qualitative data from four focus groups and quantitative data from a survey of 2,000 people in the UK. Often quoted in most of the studies about ethical consumerism, this survey still constitutes the most complete to date. It revealed five consumer segments; three of them offer major opportunities for ethical products and fair trade (see Table 1). The two most promising segments for future growth are Global Watchdogs and Conscientious Consumers, accounting for 23 per cent of the total sample (Nicholls & Opal, 2005).

| Table 1 Who are the Ethical Consumers? | ||

| Segment | Characteristics | Total market share (%) |

| Global watchdogs | Ethical hardliners. Affluent professionals typically 35-55 years old, well educated, metropolitan and South East based (particularly London), feel powerful as consumers. |

|

| 5 | ||

| Brand generation | Ethical issues secondary to brand, but can augment brand value. Young (one third under 25), often students, tend to rent housing. Midlands/North based, aware of their power as consumers, but only occasionally use it. |

|

| 6 | ||

| Conscientious consumers | Driven primarily by value and quality. Relatively up-market, not brand aware, conservative. Midlands and South East based (not London), feel some power as consumers. |

|

| 18 | ||

| “Look after my own” | Little ethical motivation. Young, on low incomes, typically live in the North and Scotland, high percentage of unemployed, often feel powerless as consumers. |

22 |

| “Do what I can” | Weak ethical motivation (but still present). Older (a quarter over 65), homeowners, typically live outside London, sometimes feel powerless as consumers. | |

| 49 | ||

The Fair Trade Consumer

De Pelsmacker et al., (2005a) found that the three main reasons for buying fair trade products were: (1) Fair price to farmers and manufacturers in developing countries; (2) Safe and honest production process and; (3) Retention of dignity and autonomy of producers. The profile of the idealised fair trade consumer appears to be a middle-aged, affluent and degree-educated woman, and fits closely with the characteristics of Cowe and Williams’s (2000; cited by Nicholls & Opal, 2005) “Global Watchdogs” segment (see Table 1).

Moreover, the Fair Trade Foundation identified four levels of target consumer: core supporters; partial adopters; occasional conscience buyers and well-wishing bystanders (Nicholls & Opal, 2005). These correspond to three of Cowe and Williams’s (2000; cited by Nicholls & Opal, 2005) segments, suggesting three major points. Firstly, there is a possible ethical market of up to 72 per cent of the population in the UK. Secondly, there will be a group amounting to approximately 30 per cent of the population who may never be prepared to engage with fair trade. Thirdly, approximately 30 per cent of the population is particularly motivated to buy ethical goods, but such products typically account for less than 1-3% of their individual markets. Consequently, “an ‘ethical gap’ may be discerned between consumer preference and action” (Nicholls & Opal, 2005:187). The remainder of the literature review critically examines the drivers behind this gap.

The Drivers Behind the ‘Ethical Purchase GAP’

Consumer goodwill and knowledge of fair trade does not necessarily translate into increased purchase of products. An investigation of the literature reveals that a short number of papers have been written on the issue of the ethical purchase gap and its origin. Here we assess the contribution of the most relevant papers.

One of the earliest studies in this area is the work entitled “The problems of translating fair trade principles into consumer purchase behaviour” by Strong (1997). She identifies three specific dimensions underlying the apparent discrepancy between expressed purchase intent and actual purchase behaviour. The author finds that the emphasis on green marketing has tended to stress the importance of the environmental dimensions of sustainability and underplay the human side, which is actually the focus of the fair trade concept. The second issue is the difficulties in establishing consumer commitment to fair trade. Strong (1997) establishes that fair trade consumers are rarely ethically consistent. More specifically, she finds that fair trade consumption is more a lifestyle attribute or an episodic phenomena rather than a real adhesion to fight social issues. The obstacles in getting more fair trade products on to supermarkets shelves are the last issue.

“Whilst these dimensions set a useful marketing agenda, in order to set out strategic solutions to these issues, it is necessary to redefine them in operational terms” (Nicholls, 2002:13). Nicholls (2002) detailed this argument in the paper “Strategic options in fair trade retailing”. According to the author, the explanation of the ethical gap begins by the lack of consumer awareness and understanding of fair trade. Consumers do not have a clear idea of what it actually means. He reported for example that in 2000, 16 per cent of consumers understood the meaning of the Fairtrade Foundation mark and only 14 per cent claimed to seek fair trade products as a result. Wright and Heaton (2006) agree with Nicholls (2002) and confirm a lack of awareness and a superficial understanding of the fair trade concept. The authors claim it will be difficult “to attain real growth in the mainstream market while the public’s ‘ignorance and apathy’ are obstacles” (Wright & Heaton, 2006:416). For instance, only one respondent in their entire focus group recognised and understood the fair trade certification mark while half of the consumers surveyed by De Pelsmacker et al. (2005a) felt they did not have enough information to be convinced to buy fair trade products.

In this sense, some studies have suggested the importance of exploring attitudes to information on fair trade issues. As Wright and Heaton (2006:420) noted, “There appears to be a conflict whereby consumers say they want to be informed but are so driven by time pressures and the need for convenience that they are not motivated to uncover the meaning of fair trade for themselves”. This statement concurs in some measure with the investigation “The myth of the ethical consumer – do ethics matter in purchase behaviour?” from Carrigan and Attalla (2001). On one hand, the latter found that if consumers were made aware of any unethical or irresponsible corporate behaviour through media exposure, this would affect their purchase decision. They argued that most consumers paid little attention to ethical considerations and for that reason, those who act on ethical intentions and sought out product-related information represented a minority. This was demonstrated by the fact that no respondent surveyed had enquired about the production of any product. Furthermore, Nicholls and Lee (2006) considered the concept of ‘moral intensity’ as an important driver of the ethical gap. Specifically, the fact that fair trade products are designed to reduce problems mainly caused by the developed world may lead to unpleasant feelings of guilt that can be minimised by rejecting the information given as true (“scepticism”) or ignoring the information (“not my problem”) given to consumers.

On the other hand, time pressures seem to reduce the search activity as well, as consumers do not wish to be inconvenienced by having to shop in different places to buy ethical products (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005b). Consumers prefer when ethical products are put on the same shelves as non-ethical products, but in a separate group. Consumers simply do not have time to take into account the ethical aspects of their purchases as they are rushing around a supermarket. This view is parallel to that of Shaw and Clarke (1999) who demonstrated that the issue of availability was pertinent to consumer purchasing behaviour.

Equally, Nicholls (2002) proposed a lack of coherence, width and depth in the available fair trade offer as a fundamental issue. Hence, Nicholls (2002) underlined the difficulty of imagining this limited and anonymous range of products being able to capture the majority of the public’s purchasing interest. De Pelsmacker et al. (2005a) confirmed this statement in their survey on attitudes towards fair trade. The respondents surveyed held that they would buy (more) products if distribution were improved. They saw the ability to buy fair trade products in an ordinary supermarket and the offering of a wider assortment as the two most important measures to incite them to buy. At the same time, these respondents would like to be better informed about fair trade issues and products; and considered point-of-sale information (such as indications in the store and the use of labels) as the most effective way to do so.

According to Nicholls (2002), another key influence on the ethical decision process would reside in the difficulty of establishing the direct benefit of fair trade to the consumer. As noted by an Asda spokesperson in Nicholls (2002:13), “the differentiation is lost on many people. It is a criticism of the people giving the message…the Fairtrade Foundation needs to be really clear about communicating the benefits of fairly traded products”. The problem is that the main point of differentiation of fair trade products lies in the development and support of producers. Consequently, this aspect can never be as tangible to the consumer as that of organic products, since the latter are commonly associated with personal health and environmental protection (Padel & Foster, 2005).

Carrigan and Attala (2001) also noted a propensity to be selectively ethical as previously observed by Strong (1997) and confirmed later by Nicholls and Lee (2006). The level of interest for an ethical issue is characterised by its direct impact on the consumer and exploitation of animals seems to engender more indignation than human exploitation. Consequently, consumers are not sufficiently compassionate about unethical work practices to pay a premium price and actively seek out such products (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005a). This is dissimilar from Shaw and Clarke (1999), and from the Co-operative Group/MORI survey (2004; cited by Nicholls & Opal, 2005), who perceived fair trade as the most important ethical issue of concern to consumers in the UK.

Furthermore, some others studies implicitly assume that the consumer needs to feel a sense of ‘making a difference’ in order secure a commitment to regular purchase behaviour and brand loyalty. In this sense, Show and Clarke (1999) identified the importance of belief formation in ethical purchasing. Their work, which followed from the research of Strong (1996), suggested that the ‘perceived consumer effectiveness’ – the extent to which consumers are convinced that their personal action will lead to a desired outcome – is one of the most influencing factors on ethical purchase behaviour. People may have positive attitudes to fair trade products, but for this particular reason, may believe that the issue cannot be solved through their own buying behaviour. Wright and Heaton (2006) also noted the need by consumers to feel that their individual contribution could really make a difference in order to make ethical choices. These arguments are consistent with Cowe and Williams (2000; cited by Nicholls & Opal, 2005:187) who proposed that the main reason behind the ethical gap is “a ‘pervading sense of powerlessness’, felt by consumers, in terms of making a real difference to the world through their consumption choices”.

However, Nicholls and Lee (2006) argued that these findings, notably from Strong (1996, 1997) and Show and Clarke (1999), may explain the formation of attitudes and beliefs regarding ethical purchasing, but do not close the gap between attitudes and purchase intentions. The two authors therefore suggested that the right question would instead be: “Why do those who have positive attitudes towards ethical products and their social benefit not actually purchase ethical products in preference to their usual brands?” (Nicholls & Lee, 2006:381). Hence, their results led to the revelation of two pieces of essential information. First, brand awareness may influence the awareness of the products, but did not appear to influence the intent to purchase or actual purchase behaviour. Second, the main reason consumers did not purchase fair trade products was that they preferred the branded alternatives. The problem is that fair trade products are competing with well-established brands, but extensive marketing communications rarely support them and as result often fail to build any competitive brand presence (Nicholls & Opal, 2005). This led Nicholls and Lee (2006) to observe that “without an influential brand, the respondents simply did not understand why they should purchase a fair trade product in preference to their usual branded item” (2006:382- 383). Consequently, they considered the lack of brand building as the strategic factor explaining the ethical purchase gap in fair trade.

In summary, a review of relevant literature established several reasons in the explanation of the ethical purchase gap. Some authors observed that consumers do not have a clear idea of what fair trade actually means (Nicholls, 2002; Wright & Heaton, 2006). Other studies reminded us that most consumers pay little attention to social issues when making a purchase; while price, quality, value, convenience for shopping and brand image remain the most important factors influencing the buying decision (Strong, 1997; Show & Clarke, 1999; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Nicholls, 2002; De Pelsmacker et al., 2005a; Nicholls & Lee, 2006).

This study investigates the attitudes held by students towards fair trade product consumption. Do students share the same attitude-behaviour gap as other Portuguese consumers? Are there any other explanations which have not yet been mentioned? The research design and methodology section explains how this paper attempts to answer those questions.

Research Design and Methodology

Research Design

The purpose of the primary research was to collect data that would result in working knowledge in order to understand and close the apparent attitude-behaviour gap between intention and actual ethical purchasing behaviour in the context of fair trade. Specifically, the objective was to explore this among a student audience and the literature review highlighted the importance of investigating the students’ perception of fair trade as a concept and product.

This research reflects the principles of ‘interpretivism’, where the researcher attempts “to show the purpose of the action, the patterns and rules being followed by the individual in that action” (Carrigan et al., 2004:406). An interpretive approach assumes that knowledge comes from the study of people’ behaviours and that the results of the analysis would allow the formulation of a theory. The need to generalise this theory is not important since “there is no ultimate proof of what is true” (Jankowicz, 2005:116) and that this approach places emphasis on the collection of qualitative data (Saunders et al., 2003).

This research is exploratory in nature given the objectives previously stated and assuming that no prior knowledge existed about students’ attitudes towards fair trade in general and to fair trade products in particular. Exploratory research is commonly regarded by the methodology literature as “ a valuable means of finding out ‘what is happening; to seek new insights; to ask questions and to assess phenomena in a new light’” (Robson, 2002:59, cited by Saunders et al., 2003:96).

Three different techniques (questionnaire, focus group and in-depth interviews) were carried out for the collection of data. For instance, qualitative research was helpful because little was known about the research problem; but also for the reason that purchasing behaviour involved complex and evolving phenomena that needed to be fully understood (Hair et al., 2007). The focus group and in-depth interviews provided in this manner “the opportunity to ‘probe’ answers, where you want your interviewees to explain, or build on, their responses” (Saunders et al., 2003:250). These two qualitative techniques, plus the questionnaire, are described in detail in the next section.

Questionnaires

Saunders et al., (2003:280) defines questionnaires as a general term that includes “all techniques of data collection in which each person is asked to respond to the same set of questions in a predetermined order”. Although questionnaires were not particularly recommended for the exploratory nature of this study (Saunders et al., 2003), the purpose of this technique here was triple. Firstly, to discover students’ attitudes to fair trade consumption. Secondly, to establish a broad basis for identifying the key themes and issues to be investigated later by focus groups and in-depth interviews. Thirdly, to use the results from the questionnaire to cross-check the results from the focus group and in-depth interviews (Jankowicz, 2005).

Self-administered questionnaires were personally distributed to every respondent and collected some minutes later. This type of questionnaire had three advantages. First, it reached a significant sample more rapidly than structured interviews and with a greater response rate than on-line questionnaires. Second, it allowed the verification of answers and thus the assurance that the respondent did not omit any question. Third, it reduced the possibility of bias towards more socially desirable answers (Saunders et al., 2003). Questionnaires were submitted over the month of December 2021 in the libraries of University of Coimbra to a convenience sample of 100 students. Accordingly, the results from the small scale of this non-probability sample were not generalised across the whole of the target population (Wright & Heaton, 2006). Nevertheless, respondents were selected in different areas to ensure a certain diversity of students in terms of year and subject of studies and thus to avoid any bias. To be sure, respondents were not influenced and did not discuss their answers with each other; questionnaires were only given in individual study places.

The questionnaire was constructed around four main parts based on the literature review and derived from the survey of Pelsmacker et al. (2005a). This survey aimed to investigate the relationship between the personal values of Belgian consumers and their attitudes and buying behaviour with respect to fair trade.

The first part of the questionnaire used closed questions to measure the level of awareness by respondents of the term “fair trade”. Then category questions were used to determine to what extent respondents were already purchasing fair trade products. In the second part, respondents were asked to rate 17 statements on a five-point Likert scale (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, with a middle “neither agree nor disagree” point of scale). These statements measured respondents’ attitudes towards fair trade in general (e.g. concern about fair trade issues, level of understanding of the concept and perceived effectiveness) and to fair trade products (e.g. product quality, appearance, availability and visibility in stores, price acceptability and buying intention). Both positive and negative statements were included “to ensure that the respondent reads each one carefully and thinks about which box to tick” (Saunders et al., 2003:296).

In the third part of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to rate 25 statements on a six-point Likert scale (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, with a middle “neither agree nor disagree” point of scale, but also with a “no answer” category). The aim of this “no answer category” was to avoid that students who had no opinion about a statement influenced the results by haphazardly selecting a scale. It was particularly relevant regarding the nature of the issues addressed by these statements (Crowe & c, W, 2000).. Indeed, six statements measured the extent to which fair trade issues were important in respondents’ purchasing behaviour. Then respondents were asked about the arguments that would convince them to buy these products (10 statements) and about the ways in which they would like to be informed about fair trade issues and products (9 statements).

In the fourth part, respondents answered questions with respect to their age, gender, place of residence, nationality and education (see Table 2). The results were analysed with the help of computer software.

| Table 2 Respondent Profiles (%) | ||

| Variable | Results | |

| Gender | Male | 39 |

| Female | 61 | |

| Age (years) | 17 | 1 |

| 18-21 | 61 | |

| 22-25 | 29 | |

| 26-30 | 6 | |

| 30+ | 3 | |

| Residency | Parent’s home | 60 |

| Private flat | 39 | |

| Own home | 1 | |

| Nationality | Portuguese | 94 |

| Other European | 5 | |

| Africa | 1 | |

| Asian | 0 | |

| American | 0 | |

| Education (year of study) | 1st year | 18 |

| 2nd year | 21 | |

| 3rd year | 25 | |

| Master year | 36 | |

| Total | N = 100 | |

Focus group

“Focus groups are semi-structured interviews that use an exploratory research approach and are considered a type of qualitative research” (Hair et al., 2007:197). They represent one of the most widely used techniques in market research and combine the advantages of speed, flexibility, economy and richness of qualitative data (Saunders et al., 2003). One focus group was conducted for this study. It aimed to validate and explore the variety of data that had emerged from the use of the previous questionnaire (Saunders et al., 2003). It was a deliberate choice to select a group of non-fair trade consumers since one specific objective of this study was to understand the barriers to fair trade consumption.

The focus group took place the 5th of January 2022 in the University of Coimbra. It lasted approximately 40 minutes and was recorded by note-taking. The idea here was more to record the arguments voiced by the participants rather than to make extensive notes. Six male participants were recruited through an acquaintance. They were a group of 19 and 23 years old, and first year Economics students at the University of Coimbra. They were native to Portugal (6), and for that reason they were also a good testing ground for fair trade awareness and understanding levels in Portugal.

Three focus groups were planned but only one was conducted because of the difficulty to manage this type of discussion.

Due to the difficulty to exploit the potential of focus groups in terms of wealth of data, it has therefore been decided to conduct five in-depth interviews more than the eight ones scheduled.

In-depth interviews

In-depth interviews are “used in qualitative research in order to conduct discussions not only to reveal and understand the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ but also to place more emphasis on exploring the ‘why’” (Saunders et al., 2003:248). In this study, in-depth interviews were used to discuss the findings from the questionnaire and the focus group; and thus to seek new aspects, issues and answers in the study of students’ attitudes towards fair trade purchase behaviour. They also aimed to investigate in detail the issues derived from the literature review, such as price perception, time pressure, product quality, availability in store and mistrust of the concept of fair trade.

Since this research is about consumer behaviour, in-depth interviews were particularly appropriate to cope with the complex nature of the questions necessary to obtain the required data (Saunders et al., 2003). In all, 13 interviews were undertaken over a period of three days in January 2022. Every interview was recorded by note-taking and lasted between 25 and 35 minutes. Participants were recruited among students (9 participants, including 6 non-consumers of fair trade) and in the University of Coimbra (4 participants, including 2 non-consumers).

A larger sample of non-fair trade consumers was selected on purpose as this study particularly explores the barriers to buying fair trade products. Both the focus group and in-depth interviews contained different types of question: open (e.g. What do you think about the promotion of fair trade products in supermarkets?), probing (e.g. How do you perceive the price of fair trade products?) and closed questions (e.g. Do you actually purchase fair trade products?). Word-for-word quotations were captured during the interviews. The answers were categorised in accordance with the three objectives of this study. Table 3 establishes the demographic profile of each interviewee.

| Table 3 Demographic Profiles of the Different Interviewees | ||||

| Interview number | Gender | Age | Education | Buyer of fair trade products |

| 1 | Female | 23 | BA Economics, 2nd year | No |

| 2 | Female | 29 | MA Biology | No |

| 3 | Female | 22 | MA Economics | No |

| 4 | Male | 20 | BA Management, 1st year | No |

| 5 | Male | 22 | BA Management, 1st year | No |

| 6 | Female | 20 | BA Mathematics, 3rd year | No |

| 7 | Male | 26 | MA Medicine, 2nd year | No |

| 8 | Male | 23 | BA Law, 3rd year | Yes |

| 9 | Female | 22 | BA Mechanical Engineering, 2nd year | Yes |

| 10 | Male | 22 | BA Mechanical Engineering, 2nd year | No |

| 11 | Male | 24 | BA Psychology, 3rd year | Yes |

| 12 | Female | 23 | MA Law | Yes |

| 13 | Male | 27 | BA Economics, 3rd year | Yes |

Results

In this section, the results of questionnaires, focus group and in-depth interviews are compared and structured around the three research objectives of the study. The first part portrays the attitudes of students towards fair trade. Then the second part gives an idea about the sources of the ethical purchase gap for this segment. Last of all the third part presents the measures which would stimulate students to buy (more) products, and how they would like to be informed about fair trade issues and products. Representative and extensive quotations, but also charts and tables, illustrate the responses of the different participants.

Objective

Attitudes Towards The Concept Of Fair Trade And To Products

The entire focus group, all individual interview participants and 98% of questionnaire respondents were familiar with the term “fair trade”. Questionnaire respondents were also asked to indicate to what extent they knew what fair trade means. Findings revealed a good understanding of the concept for 89% of them, 4% had no opinion and 7% did not clearly know what it means (see Table 4). The focus group and in-depth interviewees also had a fine understanding of fair trade, as demonstrated by the five definitions below:

| Table 4 Do you Agree or Disagree with These Statements (%)? | |||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither…nor | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

| I don’t know what fair trade means | 2 | 5 | 4 | 46 | 43 |

| I don’t know what types of products are available | 1 | 13 | 14 | 54 | 18 |

| I don’t trust these products | 0 | 0 | 17 | 40 | 43 |

| I cant find them in store | 1 | 17 | 30 | 36 | 16 |

| Supermarkets promote fair trade products in stores | 5 | 47 | 25 | 22 | 1 |

| Fair trade products are high-priced | 7 | 53 | 25 | 13 | 2 |

| They have poor appearance | 0 | 6 | 38 | 47 | 9 |

| They are not available in my store | 2 | 16 | 23 | 46 | 13 |

| They have a better quality than traditional items | 2 | 18 | 66 | 13 | 1 |

| They don’t have anything to offer | 2 | 7 | 21 | 51 | 19 |

| I am satisfied with the non fair trade products | 7 | 55 | 28 | 9 | 1 |

| My friends or my family buy fair trade products | 6 | 48 | 19 | 21 | 6 |

| I don’t care about ethical issues | 1 | 5 | 15 | 45 | 34 |

| Fair trade products offer fair prices to farmers of developing countries | 21 | 56 | 18 | 5 | 0 |

| Fair trade products come from safe and honest production processes | 16 | 47 | 33 | 4 | 0 |

| Fair trade products help the retention of dignity and autonomy of producers | 14 | 43 | 39 | 2 | 0 |

| I would buy them if I was sure they improve the life of disadvantaged producers | 25 | 45 | 23 | 5 | 2 |

| N = 100 | |||||

“Making sure that producers in poor countries get a fair price for their products.” (Interview 1)

“Fair trade is a way of doing business that allows a fair price for the producers.” (Interview 8)

“Fair trade is a process that helps the local people of a country to earn a fair living economically.”

(Interview 11)

Only one interviewee was unable to provide a clear definition:

“I think I know what fair trade means but I don’t have a clear definition in mind […]

Do you know if fair trade is environmentally friendly?”(Interview 2)

Another interviewee had, according to his own words, a provocative idea of the fair trade concept:

“I think that fair trade is a label that is attached to a product; almost as a brand; in order to justify

an increased price for the product, which gives you a well- being feeling that the product has

been fairly produced, and which may or may not be necessarily true.” (Interview 7)

Furthermore, questionnaire respondents demonstrated knowledge of the principles of fair trade and generally believed in its benefits. For instance:

• 77% agreed and strongly agreed with the statement “Fair trade products offer fair prices to farmers in developing countries”;

• 63% judged that “Fair trade products come from safe and honest production processes”;

• 57% considered that “Fair trade products help the retention of dignity and autonomy of producers”;

• 70% disagreed and strongly disagreed with the fact that “They don’t have anything to offer”; and ultimately,

• 0% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I don’t trust these products” (Table 4).

A majority of in-depth interviewees supported this view, both fair trade and non-fair trade consumer, and comments included:

“I trust fair trade in the sense that there is nothing wrong with the quality.”

(Interview 7)

“I think fair trade is effective. I believe it gives producers a fair income.”

(Interview 8)

In other respects, two fair trade consumers were unable to show evidence of its effectiveness:

“I think fair trade is effective but I don’t know obviously.” (Interviewee 12)

“If it is done properly it would be effective. Although with some of the fair trade product organisations,

I don't know if the wealth is truly filtered down in the right way.” (Interview 13)

One fair trade consumer also highlighted the need to reach the mainstream market to be truly effective:

“I think it is effective but it is a small market. So it is probably an effective idea but the fact that it is not

a big market will not hold huge effects on developing economies.” (Interviewee 11)

Additionally, one non-fair trade consumer who expressed a large interest in ethical behaviour had doubts about the transparency of the concept:

“I don’t know if I can trust fair trade. For example, how can big brands like Nescafe sell fair

trade products and non-fair trade products? It is not logical.” (Interview 1)

What is more, the entire focus group and the individual interviewees who had little interest in ethical behaviour did exhibit a negative attitude towards this type of commerce. For instance, they had important reservations about its effectiveness:

“I don’t trust fair trade products because I am not entirely sure if the money goes to these

people.” (Interview 3)

“I don’t think fair trade is effective so I consider it useless to buy these products.

(Interview 4)

“Fair trade is just a tool to make money.” (Interview 5)

Fair trade did not seem close to the members of the focus group, as highlighted by one of them:

“It is difficult to know if fair trade is effective and to appreciate its benefits. Producers are so distant

from where we live.” (Focus group)

Another member of the focus group spontaneously added:

“I know a story about Starbucks which made people pay extra money for a fair trade coffee.

But the scandal was that this money did not go to poor farmers and producers at all.” (Focus group)

In other respects, 75% of questionnaire respondents revealed they knew how to identify a fair trade product (Table 4). 72% also demonstrated good awareness of fair trade product categories; even though 14% did not know what types of products were available (Table 5). Again, these results were confirmed by the focus group and individual interviews. All the interviewees recognised the fair trade certification mark and also demonstrated good awareness of fair trade products, including awareness of where to buy them. For instance, coffee, tea, bananas and chocolate were the most frequently mentioned goods. Fair trade consumers bought such products mostly in supermarkets, but also in coffee shops, as confirmed by the quotations below:

| Table 5 Do you Agree or Disagree with These Statements (%)? | ||||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither…nor | Disagree | Strongly disagree | No answer | |

| Fair trade are important to me | 1 | 20 | 56 | 19 | 4 | 0 |

| I would be interested in knowing how fair trade products are produced |

7 | 65 | 16 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| Before buying, I compare them with conventional products |

5 | 37 | 28 | 25 | 4 | 1 |

| The way a product is produced influences my buying decision | 6 | 32 | 39 | 17 | 6 | 0 |

| I know how to identify a fair trade product | 17 | 58 | 11 | 11 | 3 | 0 |

| N=100 | ||||||

“I buy many types of products, like bananas, coffee, tea, chocolate bars…but also clothes via on-line.

I often go to “Baixa “. But I prefer big shopping malls because it is more convenient.

The products I want are always available and there is more choice.” (Interview 8)

“My dad buys chocolates from the local Lidle store.” (Interview 9)

“I sometimes buy fair trade coffee. This may be on any other major coffee franchise.” (Interview 11)

Moreover, only three participants were able to cite a fair trade brand. Responses included only Body shop. With regard to the issue of branding, another participant remarked:

“I don’t know any fair trade brand but I think that fair trade operates as a brand by itself.

When I see a product, I only notice the certification mark.” (Interview 7)

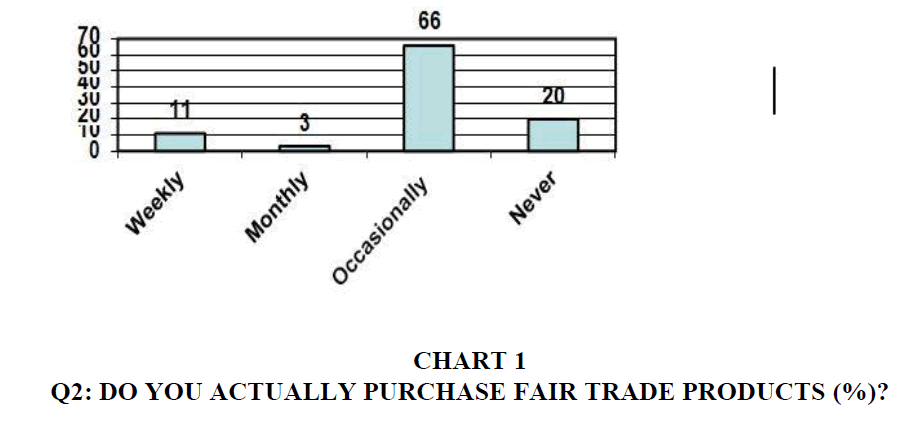

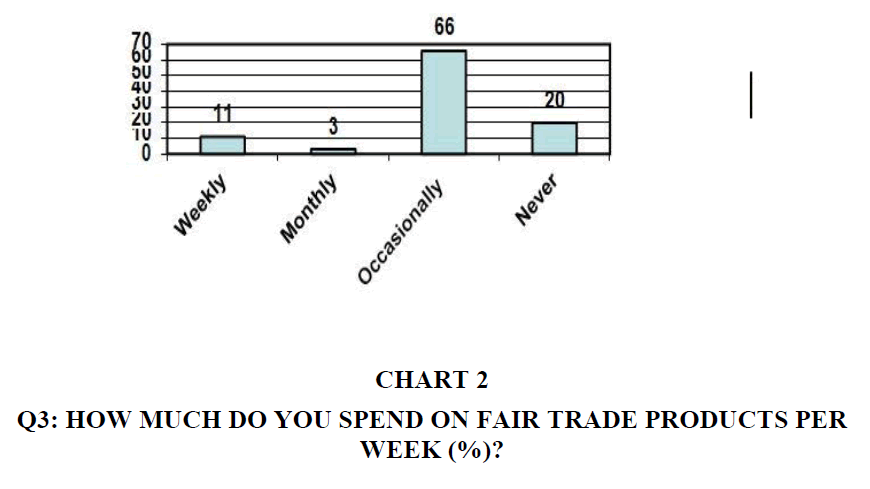

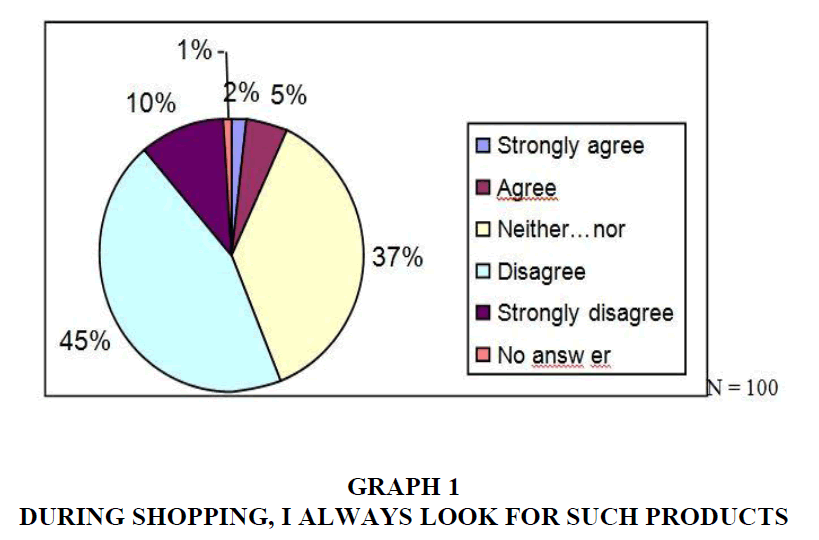

The buying frequency – the number of times a respondent has made a purchase of one or more fair trade items – and the amount of money spent on fair trade products is showed respectively, in Chart 1 and Chart 2. The spending patterns were significantly different between participants of questionnaires, focus group and in-depth interviews. For instance, 80% of questionnaire respondents (Chart 1) and five in-depth interviewees had already bought fair trade products and 54% affirmed that their friends or family were already buying these products (Table 4). Moreover, only 7% of questionnaire respondents had always shopped for fair trade products (Graph 1); while 72% claimed to be satisfied with the non-fair trade products (Table 1). Another remarkable result appears when it comes to investigating how much students spent per week (Chart 2). Indeed, findings from questionnaires revealed that “32% of respondents” did not spend any money on fair trade, despite the fact that “only 20%” admitted to having never bought such products.

The main motives for buying fair trade products that were cited in the interviews were both the belief in the effectiveness of fair trade to resolve ethical issues and the superior quality of the products, as commented by these two interviewees:

“I don’t like how Western Economies are doing business with the developing world.

I think fair trade is effective and useful. I just believe it is the right thing to do […]

I really like the products. Sometimes they are of better quality than many other products.

Coffee is nicer but the wine is not.”(Interview 8)

“I want to help the farmers in poor countries.

I believe in ethics and I think it is a good idea […] I like the taste of the tea.

I think it is of better quality than the others brands of tea.” (Interviewee 12)

Interestingly, the other three fair trade consumers did not express more than one motive for buying such products:

“Of course fair trade products are of better quality. It is like organic.

They are much wealthier.” (Interview 9)

“When I buy these products I buy them for the charity factor.” (Interview 11)

“I buy because I feel strongly toward wealth being evenly distributes” (Interviewee 13)

In addition, 20% of questionnaire respondents perceived fair trade products as being of higher quality than others (Table 4). One non-fair trade buyer who argued that the quality was just made-up by the consumer commented this result:

“Buying fair trade makes you enjoy the product more. It’s like the perceived effect theory.

Fair trade tea doesn’t taste any better than normal tea.

You feel happier buying these products so you make them tastier.” (Interview 7)

Surprisingly, a fair trade consumer put into perspective the importance of product quality for fair trade:

“I think the whole idea is to help people financially - not for the product to be of a higher quality than

other products.” (Interview 11)

The questionnaire respondents seemed to care about ethical issues as well. Respectively 45% and 34% of respondents disagreed and strongly disagreed with the statement “I don’t care about ethical issues”, while only 6% agreed and strongly agreed with it (Table 4). Finally, 21% viewed fair trade products as important to them; 42% compared fair trade products with conventional ones; and only 38% stated that the way a product is produced influences their buying decision (Table 5).

Barriers to Purchase

Questionnaires, focus group and in-depth interviews also discussed the potential issues of price, price perception, time pressure, availability and visibility in store, product appearance and mistrust of supermarkets. According to the questionnaire results, price was the main barrier for buying fair trade products. For instance, 60% of them agreed and strongly agreed that these products are high priced, while only 15% disagreed and strongly disagreed with this statement (Table 4). The focus group and all the in-depth interviewees shared this opinion. When asked for their first association with the term “fair trade”, they associated it in relation to the high price (“expensive”, but also “over- priced”). Accordingly, non-fair trade consumers saw in the combination of a high price and a low food budget the main barrier for buying such products:

“I don’t buy fair trade products often because I don’t usually have the money to

spend on such products.” (Focus group)

“I feel guilty but my budget is limited so I go for the cheapest goods.” (Interview 1)

“I’m not willing to pay for fair trade products if their price is double.”

(Interview 2)

“I don’t buy fair trade because it is expensive.” (Interview 6)

“What is the point in buying fair trade apricot jam when it costs 10cents more

than Lidle ‘the best range’ and the quality is probably the same?”(Interview 7)

“I can’t afford to buy them. I’m used to buying the cheapest food” (Interview 10)

The non-fair trade consumers who had little interest in ethical behaviour were particularly sceptics about the premium price of fair trade products (Loureiro et al., 2002). As example, one interviewee believed that the high price is not justified and supermarkets appeared to have a negative connotation as a result:

“I see no reason why fair trade products should be more expensive than normal products.

Does that mean that producers of normal products are badly threatened or that the

supermarketsmaking more money?

I am interested to know what is the profit margin of these products. […].

It is only the way supermarkets are discriminating between rich and poor customers.

So supermarkets put a high price on these products by the lone justification that they are ethical and

that the other products are not.” (Interview 7)

In other respects, product appearance, quality, availability and promotion in supermarkets seemed to be a major issue for fair trade consumers and non-consumers sympathetic to fair trade. Conversely, a remarkable result is that availability of fair trade products were considered as a minor issue by the focus group and the others interviewees who expressed a negative attitude towards fair trade:

“I don’t buy fair trade, and even if there were more fair trade products in my store

I would not purchase them.” (Interview 6)

“No matter how many types of products are available, if they are still higher priced than

normal products, I will not buy them.” (Interview 7)

More to the point, respectively 56% and 59% of questionnaire respondents disagreed and strongly disagreed with the statements “Fair trade products have poor appearance” and “Fair trade products are not available in my store” (Table 4). With regard the promotion of these products, 52% agreed and strongly agreed that “Supermarkets promote fair trade products in store”. Meanwhile, 18% agreed and strongly agreed with the statement “I cannot find them in store”.

Making Recommendations

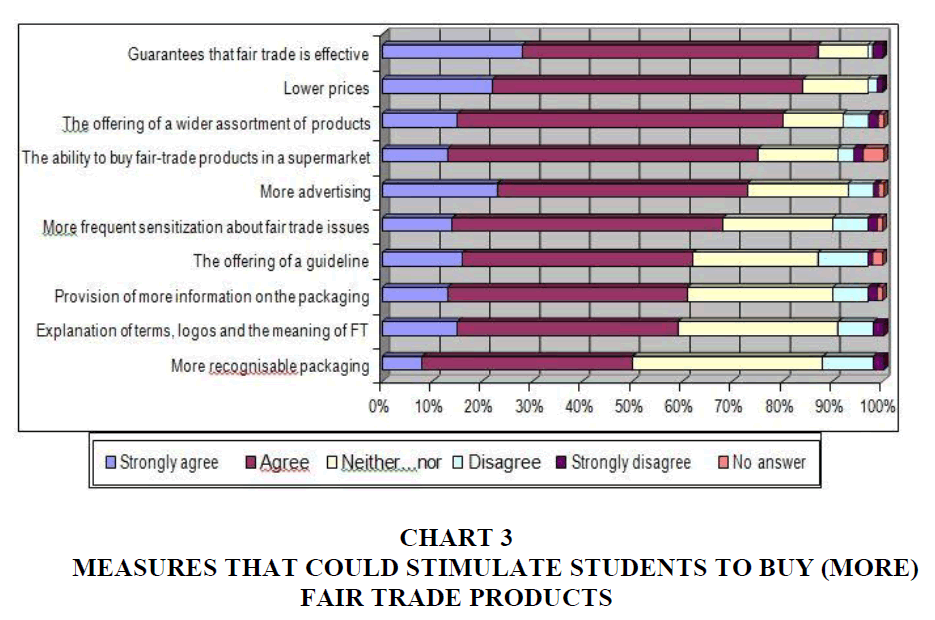

Then questionnaires respondents were asked to indicate to what extent a number of measures would stimulate them to buy (more) fair trade products. Scores were noticeably different between all the proposed measures. For instance, the guarantee that fair trade is effective, lower prices and the offering of a wider assortment of products were by far the most popular measures (Chart 3), as illustrated by these two fair trade consumers:

“Lower price would make me purchase more fair trade products as I would find them more affordable.

If there was a wider range of products this might influence me to buy more.” (Interview 11)

“I think the offer is ok but I would buy more if there were more products available. For example,

I can’t find any fair trade honey in supermarkets.” (Interviewee 12)

Meanwhile, fair trade consumers defended the high price of these products, as illustrated by the three comments below:

“I disagree. I think that the price is fair. It is fair to pay more for a good cause.”

(Interview 8)

“I think the price of these products is to be expected. I don’t think they are overpriced

when considering the

concept behind the product.” (Interview 11)

“Price is not a problem. It is a little more expensive but it is fine.

I am willing to pay more for fair trade”(Interviewee 12)

On the other hand, all the non-buyers of fair trade goods saw a lower price as the most important reason to think about fair trade. Product quality was also mentioned:

“I will buy fair trade if it was the same price and the same quality.” (Interview 4)

“To be convinced to buy fair trade, the price needs to be the same because

I am a price-conscious consumer. I think that the majority of students are like me.

It is all about value for money isn’t it?” (Interview 5) “Why not if there is a special offer.

The price has to be interesting.” (Interview 6)

“When I go shopping, price is the first thing I look at.

The second thing is quality and the third one is the service of the shop.

People are satisfied since they can find cheap goods. It is the sad truth of life.

People are egocentric when they go shopping, and that includes myself.”(Interview 7)

Interestingly, one non-fair trade buyer confirmed that the ethical aspect of a product does not influence his buying behaviour:

“I buy the product I like. It does not matter if it is fair trade or not. (Interview 4)”

Another interviewee commented:

“If every product was fair trade, what is the point of buying fair trade? Fair trade products will

loose their value. Fair trade is a symbol implying a high price and this high price implies high value.

If you say that the cheaper product on the shelves is from fair trade, people will be asking:

How can it possibly be fair? The high price protects the value of fair trade.” (Interview 7)

In addition, when asked if they would buy fair trade products if they were sure that such products improved the life of disadvantaged producers, questionnaire respondents agreed by 70%, 23% had no opinion, and 7% disagreed and strongly disagreed (see Table 4). Another result was that the provision of more information on the packaging, the explanation of fair trade and a more recognizable packaging seemed to be less desirable. Furthermore, when contrasting the individual interviews of non-consumers sympathetic to fair trade and those of non-consumers who were doubtful about it, it appeared that the latter would not be convinced to purchase such products even if they had the assurance that it was effective and even if a wider assortment was available.

Finally, questionnaire respondents were also demanded how they would like to be informed about fair trade issues and products. There were noticeable differences between the proposed promotional tools. For instance, while respondents preferred product labels, indications in stores and mass media advertising; promotion at the university and distribution of brochures were not particularly welcomed. It also worth noting that almost 15% of respondents were not interested in being informed (see Chart 4). The focus group and in-depth interviews participants confirmed this reality as they did not receptive to more information about fair trade:

“I don’t care about what my university says.” (Interview 3)

“More advertising will not influence my choice. Why spend more money on advertising if this

money could go to farmers instead?” (Interview 4)

“Why be informed if we know everything about it?” (Interview 5)

“People are brainwashed by advertising so I don’t think it will be useful.”

(Interview 7)

“I know what that means so why should I get more information.” (Focus group)

With regard to promotion in stores, one fair trade consumer argued:

“Fair trade organisations should do more promotion because people don’t know they can buy fair

trade products in supermarkets. To promote the ethical message is a good idea.” (Interviewee 12)

Discussion and Conclusions

This research aims to investigate students’ attitudes concerning fair trade. The general picture that emerges from the findings is that the recognition of fair trade is very high among students. They are also able to define the term with accuracy, meaning that fair trade is no longer a vague concept. Moreover, this research does not reveal any evidence of a lack of knowledge about the certification mark. All these results thus demonstrate a much higher level of knowledge than in previous studies (Nicholls, 2002; Wright & Heaton, 2006; Pharr, 2011).

Results also indicate that the majority of students show a positive attitude towards fair trade and judge this type of commerce as important and effective. Besides, there is an observable link between the perceived effectiveness of fair trade and their buying behaviour, thus confirming prior research (Strong, 1997; Shaw & Clarke, 1999; Wright & Heaton, 2006). The more students were convinced by the fair trade message, the more they bought these products or were predisposed to act as a result. The fact that some students believe in fair trade and are willing to purchase fair trade products, but do not, highlights the fundamental problem that positive attitudes are not always translated into buying behaviour. In this sense, the identification of the main motives and barriers to purchase is therefore primordial.

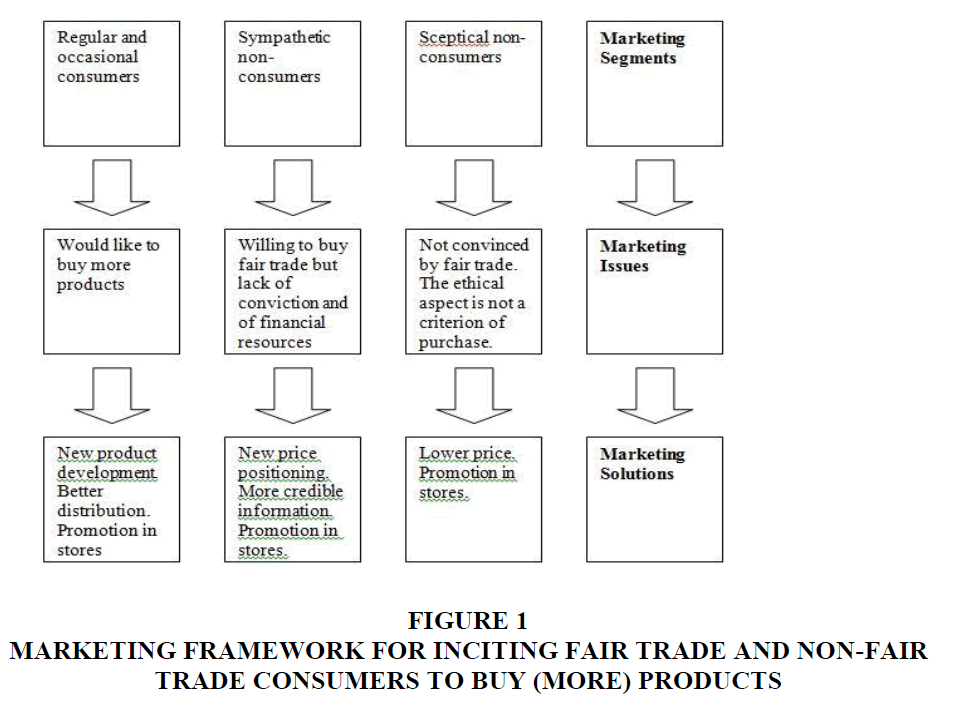

A remarkable result is that students as consumers can be differentiated into three specific segments according to their buying behaviour. Firstly, this study discerns the regular and occasional consumers of fair trade products; secondly, the sympathetic non- consumers; and finally, the sceptical non-consumers. Padel and Foster (2005) proposed a similar development in their research of buying behaviour in organic food. For instance, the two authors separated consumers into three specific groups. The first group was composed of regular consumers; the second group was composed of occasional consumers; and the last one included sceptical non-consumers. After this introduction, we now explore the attitudes of the three student segments, detail their different motives and barriers to purchase, and explain how they can be reached through marketing (Figure 1).

Figure 5 Marketing Framework for Inciting Fair Trade and Non-Fair Trade Consumers to buy (more) Products.

The regular and occasional consumers have a very positive attitude towards fair trade in general and to fair trade products. They feel well informed and strongly believe in the effectiveness of the concept to resolve ethical issues. As a result, they are willing to pay a premium price in exchange for high-quality products (Loureiro et al., 2002). This study confirms the will to help producers in developing countries, the higher quality and the taste of the products as the major motives for buying fair trade (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005; Pharr, 2011; Ladhari & Tchetgna, 2015). Findings clearly indicate that these consumers would buy more fair trade products if distribution was improved. For instance, three obstacles restrict the amount of money they can spend on them.

Firstly, there is the inconvenience of shopping in different places to find current products. The selection of the point of sale may vary from product category to product category. Although supermarkets are the prevailing place for purchasing fair trade goods, specific items like honey and flowers tend to be purchased in dedicated shops where availability is superior. Some interviewees, for example, complained they had to go on-line to buy fair trade clothes.

Secondly, the limited offer of products represents an issue. It is noticeable that these consumers expect a wider range of products. These results confirm previous studies (Strong, 1996; Shaw & Clarke, 1999; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Nicholls, 2002; De Pelsmacker et al., 2005b) that showed that availability and time pressure were critical to ethical purchase behaviour. As a third and final obstacle, it has to be noted that a limited food budget often constraints occasional consumers in their purchase intention.

The key to making regular and occasional consumers spend more on fair trade would therefore lie in the launching, primarily in supermarkets, of new high-quality products. Supermarkets combine the advantages of being the most convenient and the most visited place of purchase for fair trade products. As a result, current fair trade consumers would no longer be inconvenienced by the need to shop in different places.

Along with this suggestion, priorities must be to secure the best shelf positioning and to make sure that products are well promoted inside the store. Fair trade products should be presented separately on the same shelves that non-fair trade products; and not mixed with other brands of the same product category, or hidden away on shelves, as is commonly the case in supermarkets (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005b). The idea here would be to make them visible to both fair trade and non-fair trade consumers, and therefore to reduce the time they may spend to find such products.

Furthermore, communication should also reinforce the brand messaging through fair trade’s association with quality, as previously argued by Nicholls and Opal (2005). The purpose would be twofold. First, to ensure that a product coming from fair trade continues to be something one wants to buy rather than something one should buy; and second, to keep a coherent positioning with the high price of the products.

Finally, we think that reducing prices does not represent a major concern for marketers since these consumers are willing to pay a premium price. Nevertheless, price oriented sales promotions should incline occasional consumers to buy more regularly.

The sympathetic non-consumers express a positive attitude to fair trade as well as the wish to buy fair trade products, but the premium price has a demoralising effect. Besides, some interviewees expressed a feeling of guilt for the reason that they could not afford these products. The students included in this segment are not willing to pay a premium price because they are not always convinced that products coming from fair trade need to be more expensive than non-fair trade products; but also because they consider the premium price in the context of a low food budget. Therefore, they need more credible information and want cheaper fair trade products, as revealed by the findings of this study. Following on from this observation, this research suggests two solutions that could make them pay for fair trade products.

The first solution would consist of providing more credible information at the point of sale and on packaging. Findings suggest they are the two most desirable tactics to communicate about fair trade. The desired outcome here would be to convince the sympathetic non-consumers that the premium price is justified. The packaging could thus be the means of providing extra information (e.g. how fair trade works, who is involved…). ‘Producers ’stories’, for example, could describe how buying fair trade products influences the lives of farmers and their families. It is already possible to find this type of story on certain products, but this measure should become widespread.

The second solution would be to adapt the price positioning of the fair trade ranges. It is observable that the current premium positioning of products limits the size of market share which fair trade can address. In view of that, this research aligns itself with a strategy anticipated by Nicholls and Opal (2005). The purpose of this strategy “would be to develop the fair trade equivalent of Tesco’s Value lines that are of lower, but still quite acceptable, quality but lack any cachet or exclusivity” (Nicholls & Opal, 2005:241). Concretely, these value lines would offer poorer students who have positive attitudes towards fair trade the opportunity to buy such products without added costs and significant loss of quality.

A result of great consequence is that the lack of brand building is an important, but not the principal reason that explains the ethical purchase gap. This contrasts Nicholls and Lee’s (2006) conclusion that the lack of brand building is the key driver to explain why those who have positive attitudes towards ethical products do not buy them in preference to their usual brands. For instance, findings clearly show that these consumers prefer branded alternatives because they are distributed everywhere and are better promoted, but above all because branded alternatives are cheaper. Although this research argues that fair trade organisations should launch new products, improve their distribution, and promote the fair trade certification label as a brand; it is above all time for these organisations to consider another marketing tool, price, if they aspire to attract the segment of sympathetic non-consumers, and thus to close the ethical purchase gap suggested by Cowe and Williams (2000; cited by Nicholls & Opal, 2005). Brand image also appears to be of minor importance for ethical consumers.

Several drivers of the ethical purchase gap reviewed earlier in the literature do not appear influencing the buying behaviour of sympathetic non-consumers. However, they explain the behaviour of students who express negative attitudes towards fair trade. This aspect is discussed in detail below.

The sceptical non-consumers do not consider buying fair trade products for three reasons. Firstly, they do not perceive fair trade issues as close to them. They do not wish to be “engaged by issues that do not directly affect them, or with which they feel no sympathy” (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001:571). As example, these consumers do not see any personal benefits in buying fair trade. This also supports the work of Nicholls and Lee (2006) that described the notion of proximity as a key influence on the ethical decision process.

Secondly, the sceptical non-consumers are not convinced that this type of commerce is truthful and effective. Despite the fact that they understand the meaning and objectives of fair trade, they still argue that the premium price is pointless and only furthers supermarkets. The fundamental problem lies in the disbelief that their purchasing behaviour can make a difference to the lives of producers in developing countries, which is in line with earlier studies (Shaw & Clarke, 1999; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Nicholls, 2002; Wright & Heaton, 2006).

Thirdly, the findings prove that the sceptical non-consumers primarily expect value for money products, which is not compatible with the price premium of fair trade products. This confirms the literature reviewed herein (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; DePelsmacker et al., 2005a) that presented product price, value, and quality as the most important factors influencing the buying decision, thus ignoring the ethical aspect.

Moreover, what has emerged from the findings is that the students who are sceptics to fair trade believe that they have enough information, and that more information could not influence their purchasing decisions. Clearly, this study shows that they are not ready to be convinced by the fair trade message, and even if they were convinced, it is debatable whether or not this would make them change their buying behaviour (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001). Consequently, marketers should give them other reasons to buy fair trade products than social responsibility (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001).

This could be achieved if fair trade products were to satisfy certain criteria that are crucial for meeting the needs of these consumers. Value for money appears to be the first of them. Accordingly, this research proposes that the first measure that marketers should adopt to increase sales in the student market is the launching of a cheaper range of fair trade products in order to tackle the barrier of price. In addition, this range of products should be widely available in supermarkets, but it should also be extensive in order to meet the most common needs. Additionally, non-price oriented sales promotions in stores, like free samples, would support the launching of this new range of fair trade products.

Following on from this proposal, it is of interest to question the feasibility of all the measures discussed previously. In fact, these measures could face several challenges of growth. The following questions, among others, should therefore be addressed in order to guarantee their success:

• Where can the resources required to develop and market new products be found?

• Is the supply chain suited to fast growth? How can the reliability and regularity of supplies in this case be guaranteed? (Nicholls and Opal, 2005)

• To what extent will major retailers be keen to introduce more fair trade products in their portfolio and to promote them actively in a more and more competitive retail food market? (Jones et al., 2003)

• What will be the reactions of the regular and occasional fair trade consumers to the introduction of a cheaper range of products into the market? Will that change their attitude to current fair trade products? Will these consumers still be willing to pay for the high-priced range?

The overall aim of this exploratory research has been to understand why a specific segment of consumers – students – buy or do not fair trade products. This study has demonstrated that the student segment could be divided into three sub-segments: the regular and occasional buyers; the sympathetic non-buyers; and the sceptical non- buyers. Findings from questionnaire, focus group and in-depth interviews have stated that students shares the motives and barriers to fair trade consumption as the rest of consumers. They buy fair trade to make a difference in the lives of disadvantaged producers in developing countries, and for the quality and the taste of the products. Nevertheless, fair trade consumers are constrained by a weak offer of products and a low availability in supermarkets. This research has therefore argued the need to make more products widely available in supermarkets, to strengthen the image of the fair trade certification mark as a brand, and to encourage sales promotion in stores in order to increase sales and thus to avoid the fatigue of the movement.