Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 2S

Looking through the Lens of Gender Difference: Self-esteem and Job Satisfaction of Indian BPO Employees

Deepak Babu, Rajagiri College of Social Sciences, Ernakulam

Mani P Sam, Rajagiri Business School, Ernakulam

Imran Ahmed Khan, Rajagiri College of Social Sciences, Ernakulam

Citation Information: Babu, D., Sam, M.P., & Ahmed Khan, I. (2025). Looking through the lens of gender difference: Selfesteem

and job satisfaction of Indian bpo employees. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal,

29(S2), 1-11.

Abstract

The current global pandemic will be the catalyst to the unprecedented changes in future employment sources and location of workplace. We soon experience organizations creating feasible job locations in the post COVID era. Till now the IT enabled services and business process outsourcing (ITES/BPO) sector are at the forefront in providing employment to the less qualified, semi-skilled people cutting the gender barriers and bringing a needed change in social development of society. This sector adds their bit to the achievement of United Nations’ sustainable development goal to achieve full and productive employment and decent work for the women. The type of job and job location give one the work identity which recognizes an individual. The impact of both job location and work identity can be positive or negative. Providing job with decent work is important because it is linked to the work identity, social status and it determine the psychological state of employees in terms of their self-esteem and job satisfaction. The gender differences in self-esteem and job satisfaction among employees of Indian BPO is studied in this research work. In a mixed-effects analysis, men scored significantly higher than women on self-esteem and job satisfaction. The study also found that the women working as data entry employees in Indian BPOS actually deficient in self-esteem and job satisfaction compared to men performing the same duties. It discusses and argues about the organizational learning ability for BPOs about women workforce strategies and manpower planning based on decent work for all. This study sought to identify the antecedents and consequences of data entry job satisfaction and assess the significant relationships to their self-esteem and job satisfaction. The gender differences in job satisfaction was studied focusing on location job related self-esteem. Findings may guide employers in creating more decent jobs for less educated and semi-skilled women in small towns and rural settings especially in the post COVID era in the developing economies.

Keywords

Gender difference, Gender equality, Job satisfaction, Self-esteem.

Introduction

The Indian (IT enabled Services/BPOs) global offshore and outsourcing services industry has grown in the last four decades and from a modest $200 million in the 1980s to about $150 billion per year in the last few years (NASSCOM, 2019). This spectacular growth generate employment in India, BPO sector constitutes a tiny fraction which is 0.7 per cent of the total workforce in India. The employment through this sector has been concentrated to the socially advantaged and economically well-off sections in urban areas only. A study by (Cockburn, 1985) argues that new technology has served to reinforce the gendered division of labour; deskilling women's jobs, devaluing their position in the workforce and restricting their career prospects. A study by (Panteli et al., 1999) presents evidence that the IT industry is not gender-neutral and that it does little to promote or retain its female workforce.

Women are working in unprecedented numbers and the compensation gap between male and female pay appears to be tapering in most of the professions. According to International labour organization (ILO) women’s participation in the labour force stood at 48 per cent in 2018, compared with 75 percent for men. Around 3 in 5 of the 3.5 billion people in the labour force in 2018 were men. 2 billion workers were in informal employment in 2016, accounting for 61 per cent of the world’s workforce and there are more women (85 million) than men (55 Million) in underutilized category in the labour force. India ranked 138 globally for the labour force participation and the female worker participation is only 28.7 the gaps between men and women across all of these measures are slowly getting smaller. In 2018 the WEF report showed that 68% of the overall gap is closed, a slight rise from about 65% in 2006. Much of that has to do with educational attainment and health, where gender differences have almost vanished.

All 193 member states of the United Nations agreed in September 2015 to 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a framework of cooperation and as guideposts for national policies to achieve sustainable development around the world. The existing academic studies shows that enhancing women’s economic participation improves national economies, increases household productivity and living standards, enhances the wellbeing of children with positive long term impacts. In 1987 the Industrial Relations Research Association (The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc., Washington, D.C.) for the first time published a very important report entitled “Working Women: Past, Present, Future”. That was the milestone which endeavor addressing women issues related employment. Many studies describe how their self-esteem and satisfaction at work.

The (World Economic Forum, 2018), introduced ‘the Global Gender Gap Index’ as a framework for capturing the magnitude of gender-based disparities and tracking their progress over time. But there is still a vast gulf of available literature which explain how the type of job, location of workplace has a strong effect on the job and location related self-esteem and job satisfaction of female employees working in ITeS/BPOs in India.

Review of Literature

Self-esteem

The people’s positive view of themselves and their job may differ based on gender and location. The sociological literature provides good reason to expect that self-conceptions differ by gender. According to Lambert's "beliefs about the roles of the sexes are threads running through the fabric of society, having multiple effects upon human institutions and themselves nourished and sustained by these institutions.”

The self-esteem has been studied extensively by many social scientists and researchers in in different contexts. William James defined self-esteem in terms of competency and success in areas of life that are important to the individual (James, 1890; Mruk, 2013). In (Rosenberg, 1965) defined self-esteem as an individual’s overall sense of self-worth. Empirical evidences support the value of self-esteem. Self-esteem is generally linked with positive affect (Baumeister et al., 2003). In (Ryan, 1983) noted that high self-esteem is related to traits that are associated with humility, such as empathy, grace, contentment, honesty, and courage. In (Mruk, 2013) stressed that self-esteem functions to guide self-protection and self-expansion. Individuals with high self-esteem will seek out opportunities to grow or expand themselves and stay satisfied. In the current work we seek to establish how job location and gender are related to self-esteem. The type of job, location of job and job discretion has positive impact on performance (Cougar & Zawacki, 1980). In Morrison's view, job autonomy is also a critical success factor for women (Morrison et.al., 1987).

Many studies suggested that females have distressingly low self-esteem and it further suggest that girls and women suffer from negative self- images. Three previous meta-analyses found that the effect size for the gender difference in self-esteem was small d = 0.15; in adolescence the difference was d = 0.33, a small to medium effect size (Kling et al., 1999; Major et al.,1999; Twenge & Campbell, 2001). These previous meta-analyses examined gender differences in global context but not domain-specific self-esteem. Global self-esteem is “the positivity of the person’s self-evaluation” or “the level of global regard that one has for the self as a person” (Harter, 1993). Domain-specific self-esteem, on the other hand, describes self-satisfaction in specific areas (e.g., appearance, academics, type of employment). Self-esteem may vary considerably from one domain to another. Thus, domain-specific self-esteem may show larger gender differences than global self-esteem. The present research undertakes a comprehensive meta-analysis of gender differences in domain-specific areas of self-esteem.

In (Gentile et al., 2009) examines gender differences in 10 specific domains of self-esteem across 115 studies, including 428 effect sizes and 32,486 individuals. An influential review (Baumeister et al., 2003) found that global self-esteem was linked to happiness, but had few benefits for academic achievement, work performance, or healthy behaviors. In contrast, domain-specific measures of self-esteem are consistently correlated with performance within that domain, apparently in a reciprocal process in which each causes the other (Marsh & Craven, 2006).

Full-time housewives were hypothesized to have lower self-esteem than women in the labor force. If society devalues women generally, it assigns housewives even lower regard. If the job is socially isolated, powerless, and unpaid or less paid (Ferree, 1976).

Job Satisfaction

The job satisfaction as a positive emotional state resulting from the evaluation of one’s job experience (Okpara et al., 2005). Job satisfaction is an attitude developed by an individual towards the job and job conditions. Job satisfaction can be defined as one's affective attachment to the job viewed either in its entirety (global satisfaction) or with regard to particular aspects (facet satisfaction) (Tett & Meyer, 1993). This view supported, by defining job satisfaction as one’s reaction against his/her occupation or organization (Porter et al., 1975). There are evidences of women having lower wages, poorer job conditions, and being worse off in terms of discrimination, job content and promotion opportunities; female workers are frequently found to have equal or higher levels of job satisfaction than men (Clark, 1997; Sousa-Poza & Sousa-Poza, 2003; Kaiser, 2007, Blanchflower et al., 1999).

Most of the empirical studies probing job satisfaction based on gender recommend that women’s job satisfaction is significantly higher (Long, 2005; Clark, 1997; Bokemeier & Lacy, 1987; Hull, 1999; Kaiser, 2007). The existing studies on job satisfaction and gender offers two explanations. Firstly, it is claimed that the comparatively high level of job satisfaction of female employees may be described by their relatively low expectations of promotions or other incentives (Sloane & Williams, 2000; Sousa-Poza & Sousa-Poza, 2000). In (Long, 2005; Clark, 1997). Though better incentives and career growth opportunities may be less important for women, but they expect interesting work content and good work schedules (Bokemeier & Lacy, 1987; Clark, 1997; Bender et al., 2005). Women might be more satisfied with their jobs even when facing lower wages and having less career opportunities. We see a distinction between valence of type of job, its dimensions and job rewards. No study found which talks about job location and its effects on job satisfaction especially women job satisfaction when working in small towns.

‘How satisfied are the women with their jobs especially who work for BPOs in India?’ is a serious question because these women are not highly educated and tech savvy. Their job location, job identity and relative self-esteem plays very important role in improving their job satisfaction. Many researchers have tried to develop several types of job satisfaction scales to measure the level of job satisfaction or to improve the job satisfaction of employees in an organization. In (Greenberg & Baron, 2008), states that job satisfaction is a persons’ positive or negative feelings about their job.

Locke stated flexible timing, job sharing, shorter workweeks are quite valued by employees and the job activities such as pursuing hobbies. There are studies which prove gender is linked to commitment and job satisfaction. In (Clark, 1997) stated that ‘unless some factors were remained constant, the job satisfaction of women was higher than men’. The gender wage differential has long been considered an important research topic (Blau & Kahn 2017; Ku & Salmon 2012). Even though gender wage differentials have decreased over time, they still exist and are the subject of many studies. In (Kaiser, 2007) studies 15 EU countries and found that women have greater job satisfaction than men in labour markets that are more restrictive for women. In (Sloane & Williams, 2000), in another highly cited paper suggested that the determinants of job satisfaction for women and men differ. In (Redmond & McGuinness, 2019) found that Gender gap exists in job satisfaction because women have lower expectations than men.

Many studies confirmed that women are more satisfied than men at work (Phelan, 1994; Mueller & Wallace, 1996; Clark, 1997; Sloane & Williams, 2000). At the same time women face disadvantages on the labour market with respect to employment (Azmat et al., 2006) and wages (Weinberger, 1998).But in current study women are engaged in data entry job only and purpose of study is see how their job identity and job location affect their self-esteem and ultimately their level of job satisfaction. It was confirmed that women have higher level of job satisfaction than men because of two important factors

Method

To collect data from the employees of a firm working in online transaction processing department, prior permission was taken from firm management to conduct study based on employee self-esteem and job satisfaction. The data were collected from four different centers out of them two each are in rural and urban segment. The researcher introduced the research idea to 627 employees working in the firm during a formal event. During this event a short survey was circulated to the respondents with one inclusion question, that they were working in organization more than 2 years. The demographic analysis of the sample shows that mean age of the respondent is 27.70 (SD=8.99) with married people constitute 61.8% of the responses as 38.2% were unmarried. Among the respondents in the survey majority have completed their graduation (55.2%) followed by higher secondary (27.3%). On basis of religion majority of respondent belongs to Hindu religion 48.4% followed by Christian (29.3%).

The respondents completed a survey comprised of Macdonald and MacIntyre’s 10 item job satisfaction scale. This scale is prominently used to measure a workplace job satisfaction among the employees. For measuring self-esteem revised version of Janis and field feeling of inadequacy scale was used which comprises of 26 items. All the items are based of semantic scale from 1 to 5-point scale comprises of term such as ‘very often’, ‘fairly often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘once in a great while’ or ‘practically never’. To establish the reliability of the scale Cronbach alpha was calculated for self-esteem (0.804) and job satisfaction (0.811) which shows values are above the cutoff value of 0.7, so this result shows that instrument used for the study is reliable.

The convergent validity and discriminant validity were calculated based on the values of mean, standard deviation, composite reliability and average variance extract. The mean and standard deviation was calculated through finding average values of all items that comprise the construct under study. The confirmatory factor analysis loading values obtained provided AVE and CR values for each construct. According, the permissible limit of CR requires that all variables show satisfactorily high values (0.81). Inter-factor correlation was established to show that the constructs under study are related as per the hypothesized statements. The convergent validity of all latent variables we tested from the standardized path loading of scale items for different constructs. This showed a range of values from 0.6 to 0.91, which indicates that it is above the permissible limit of 0.5. In Table 1, standardized CFA factor loadings are provided along with Cronbach alpha values. Average extract variance estimates are also greater than the permissible limit of 0.5 and the values are shown in the diagonal position in Table 1 below.

| Table 1 Descriptive Statistics, Composite Reliability, Ave and Inter-Factor Correlation Estimates | ||||||

| Composite Reliability | Cronbach Alpha | Mean | Std. Deviation | Self-esteem | Job Satisfaction | |

| Self-esteem | 0.82 | .804 | 3.90 | 0.63 | 0.502 | |

| Job satisfaction | 0.89 | 0.811 | 4.10 | 0.20 | .424** | 0.677 |

Analysis and Finding

In this study based on the responses of 395 employees from ITeS firm tried to test hypotheses that there is a significant difference of job satisfaction and self-esteem between female and male employees. For testing this hypothesis independent sample t test was conducted and the results are depicted in the table below. The distribution of self-esteem and job satisfaction among male and female are varied considerably within sample group. For male self-esteem was in a range of 1.734 (min) to 4.82 (max) with a mean score of 3.99(SD=0.45) and in female group self-esteem was in the range of 2.37 (min) to 4.9 (max) with a mean score of 3.89(SD=0.69). Further, in case of job satisfaction in male group range varies from 1.9 (min) to 4.7 (max) with a mean score of 3.19(SD=0.67) and female group shows a range of 1.03 (min) to 4.32 (max) with a mean score of 2.6 (SD=0.65). The result here shows that there is no significant difference between male and female respondent based on perception of self-esteem and job satisfaction Table 2.

| Table 2 Group Statistics | |||||

| Gender | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

| Self-esteem | Female | 128 | 3.8906 | .45150 | .03991 |

| Male | 267 | 3.9963 | .69238 | .04237 | |

| Job satisfaction | Female | 128 | 2.6695 | .65539 | .05793 |

| Male | 267 | 3.1970 | .67081 | .04105 | |

Furthermore, based on a priori prediction that location of the people residing has a significant influence on their self-esteem and job satisfaction. Thus, a general linear model was run to find the interaction effect of location with gender on perception on job satisfaction. The table with result is provided below Table 3.

| Table 3 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Job Sat | ||||||

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

| Corrected Model | 85.619a | 3 | 28.540 | 99.013 | .000 | .432 |

| Intercept | 3021.816 | 1 | 3021.816 | 10483.633 | .000 | .964 |

| Location | 60.772 | 1 | 60.772 | 210.838 | .000 | .350 |

| Gender | 16.932 | 1 | 16.932 | 58.741 | .000 | .131 |

| Location * Gender | 4.129 | 1 | 4.129 | 14.325 | .000 | .035 |

| Error | 112.702 | 391 | .288 | |||

| Total | 3815.390 | 395 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 198.321 | 394 | ||||

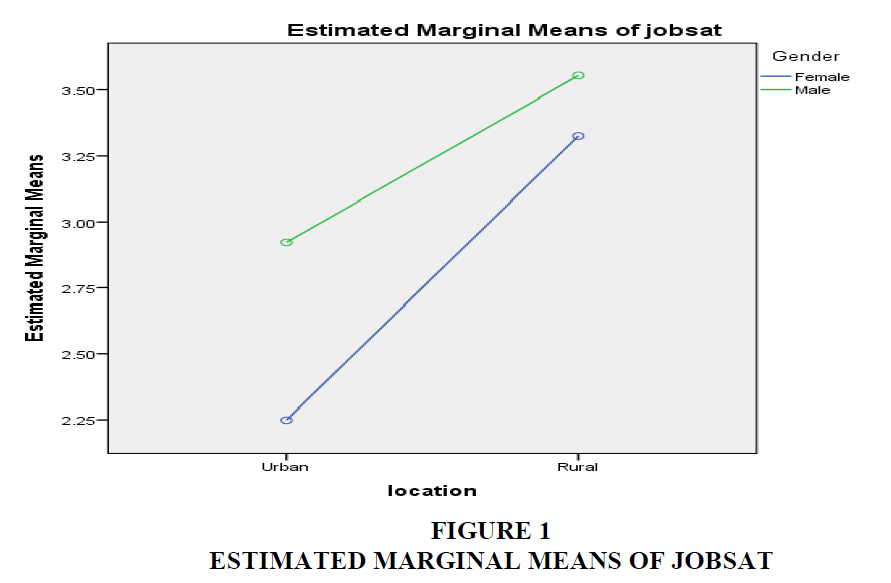

From the result, it is depicted that main effect of location is significant F (3, 391) = 60.7 at significance level of 5%. Further, it shows that main effect off gender is significant F (3, 391) = 16.9 at significant level of 5%. The interaction effect location and gender shows a significant effect on job satisfaction and the estimated marginal means plot shows that female (Mean=2,24, S.D= 0.061) in urban location are less job satisfaction as compared to male (Mean=2,92, S.D= 0.044) from urban location. This result is consistent with female (Mean=3.326, S.D= 0.076) in rural location is also showing higher satisfaction as compared to male (Mean=3.554, S.D= 0.050) in rural location. It is further shown in the data that female (Mean=3.326, S.D= 0.076) from rural location shows higher job satisfaction as compared to female (Mean=2,24, S.D= 0.061) in urban sector. Further, the result among male (Mean=3.554, S.D= 0.050) in rural sector is showing higher job satisfaction as compared to male (Mean=2,92, S.D= 0.044) in urban location Figure 1.

To estimate the influence of gender and location on self-esteem of the employees a general linear model was run to find the interaction effect of location with gender on perception on self-esteem. The table with result is provided below Table 4.

| Table 4 Tests of Between-Subjects Effects | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Self Esteem | ||||||

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

| Corrected Model | 100.376a | 3 | 33.459 | 242.290 | .000 | .650 |

| Intercept | 5347.196 | 1 | 5347.196 | 38721.564 | .000 | .990 |

| Gender | 1.466 | 1 | 1.466 | 10.617 | .001 | .026 |

| location | 56.954 | 1 | 56.954 | 412.434 | .000 | .513 |

| location * Gender | 10.920 | 1 | 10.920 | 79.077 | .000 | .168 |

| Error | 53.995 | 391 | .138 | |||

| Total | 6354.940 | 395 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 154.370 | 394 | ||||

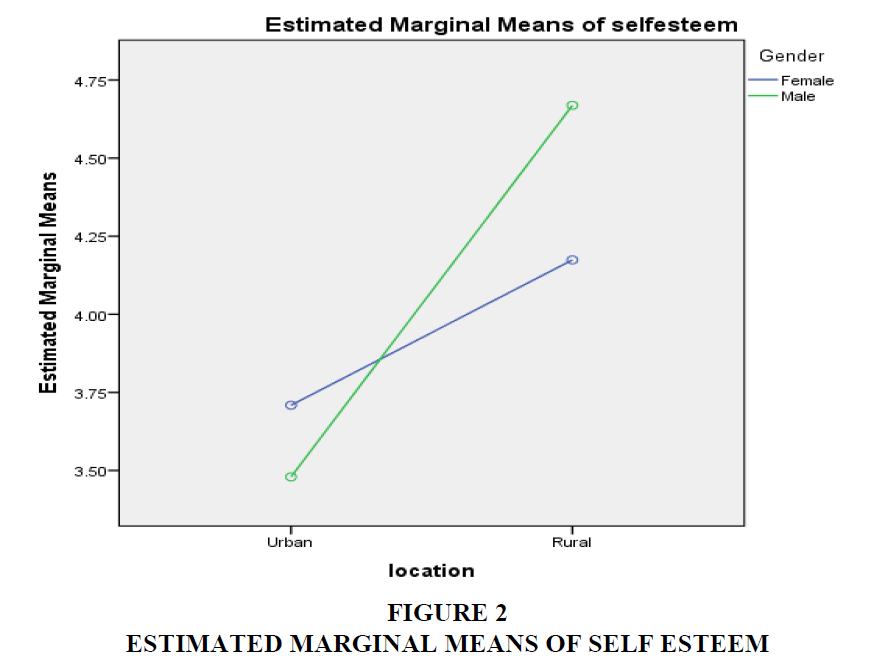

From the result, it is depicted that main effect of location on self-esteem is significant F (3, 391) = 56.9 at significance level of 5%. Further, it shows that main effect of gender on self-esteem is significant F (3, 391) = 1.46 at significant level of 5%. The interaction effect location and gender shows a significant effect on self-esteem and the estimated marginal means plot shows that female (Mean=3.7, S.D= 0.36) in urban location are higher self-esteem as compared to male (Mean=3.47, S.D= 0.39) from urban location. This result is not consistent with female (Mean=4.17, S.D= 0.42) in rural location is also showing lower self-esteem as compared to male (Mean=4.66, S.D= 0.31) in rural location. It is further shown in result that female (Mean=4.17, .D= 0.42) from rural location shows higher self-esteem as compared to female (Mean=3.7, S.D= 0.36) in urban sector. Further, the result among male (Mean=4.66, S.D= 0.31) in rural sector is showing higher self-esteem as compared to male (Mean=3.47, S.D= 0.39) in urban location Figure 2.

Discussion

The issues involved appears to be much deeper and involved than what meets the eye. Our study tried to link self-esteem and job satisfaction with the job location. It was also assumed that the rural locations offered women higher self-esteem and job satisfaction than the urban location. There are varieties of theories of Self-esteem, or instance global self-esteem which refers to the overall aggregated opinion of oneself at any one time, on a scale between negative and positive (Harter, 1993; Kling et al., 1999 ) or domain specific self-esteem which relates to one’s self-esteem in regard of a particular area, such as a white collar IT Job or defense service for a nation etc.; or trait self-esteem which described as an individual’s accumulated lifelong perception of social inclusion and exclusion.

William James is repeatedly referred to as the creator of the self-esteem movement (Kling et al., 1999) and his formula of self-esteem appears to be well respected, which is based on two elements, feeling good about ourselves (pretensions) and how well we actually do (success), are inextricably linked; we can feel better about ourselves by succeeding in the world but also by varying the levels of our hopes and expectations. In this study employees from small towns working for BPO as a white collar employees feel good about themselves and see them successful against the local hopes and expectations.

However, when we find that the self-esteem and job satisfaction is lower irrespective of the job location them the underlying root causes need careful study. It has major impact when “Work from Home” becomes essential and more and more rural women are drawn into the workforce. The Maslow’s needs hierarchy theory (1943) is based on human needs play important role in job satisfaction. Once the basic needs satisfied, the employee will seek for self-esteem needs to feel as though they are valued and appreciated by their colleagues, organization and community. The ‘Job Characteristics Model which is based on five key job characteristics: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy and feedback, influence the psychological states. In this study authors are trying to establish the relationship between job related self-esteem and job satisfaction.

Managerial Implications

COVID 19 has established that working from home is a very valid form of professional employment and it was also observed that many of the ITES and BPO employees actually moved back to their hometowns and parental homes during the pandemic. Our study conducted before the pandemic had found that the Rural Job locations had offered higher job satisfaction and self-esteem to both the genders (we did not have any one classifying as the third gender and hence the study had to limit itself to male and female genders alone.

The lower self-esteem and job satisfaction experienced by the female workers may reflect the influence of many factors. It may be possible that the female workers are less mobile when compared to their counterparts and hence it may not have been able for them to opt for better positions even if available at another location. The upward mobility of data entry operators is limited as the steep pyramidal structure of the setups and there may be a single supervisor for almost 30 workers. At entry level job positions the stress and feelings of homemakers may not be fully erased, as many of them doubled as home makers in addition to the data entry job. (One location even had a homemaker shift which started late to accommodate mothers with school going kids, and it was found that they had completed all the cooking for the day before coming to the work place.

Similar predicament was experienced by working mothers when they switched to work from home as the kids (who were also at home due to shutdown) demanded more attention and care from their mothers.

It may be true that the society need to change as mentioned in the HBR article “Gender Equity Starts in the Home.” Despite the fact that women outnumber men in the paid workforce, women still do more of the domestic work and childcare almost twice as much as their male partners.

There is another aspect which need to be considered. Since there were unmarried females in the survey, does the result indicate a continuing bias towards female participation in domestic work, which is leading to low self-esteem and job satisfaction among the female workers? The nature of job and compensation were the same and hence this seems to be one of the possible factors which caused this differential.

Work place culture should also be truly inclusive to have remove the gender bias in job satisfaction and self-esteem. An inclusive environment is essential for everyone to learn and grow.

The impact of such engagements on their wellbeing may be quite detrimental if the “official work” is just added to her domestic chores. There is a need for social sensitization of men as well as older women so that there is an earnest attempt to share the other chores of a woman working from home.

Organizations should start gender sensitization lessons for their employees at all levels to remove the straight jacketing of domestic work and childcare with a specific gender. De-gendering of office jobs is progressing rapidly but a faster adaptation at home front may be the urgent need. Last but not the least, organizations should promote an inclusive workplace culture.

References

Azmat, G., Güell, M., & Manning, A. (2006). Gender gaps in unemployment rates in OECD countries. Journal of Labor Economics, 24(1), 1-37.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological science in the public interest, 4(1), 1-44.

Bender, K. A., Donohue, S. M., & Heywood, J. S. (2005). Job satisfaction and gender segregation. Oxford economic papers, 57(3), 479-496.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1999). Well-being, insecurity and the decline of American job satisfaction. NBER working paper, 7487.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of economic literature, 55(3), 789-865.

Bokemeier, J. L., & Lacy, W. B. (1987). Job values, rewards, and work conditions as factors in job satisfaction among men and women. The Sociological Quarterly, 28(2), 189-204.Indexed at, Google Scholar

Clark, A. E. (1997). Job satisfaction and gender: why are women so happy at work?. Labour economics, 4(4), 341-372.

Cockburn, C. (1985). Machinery of dominance: Women, men and technical know-how. London; Dover, NH: Pluto Press.

Cougar, J., & Zawacki, R. (1980). Managing and Motivating Computer Personnel.

Ferree, M. M. (1976). Working-Class Jobs: Housework and Paid Work Assources of Satisfaction. Social problems, 23(4), 431-441.

Gentile, B., Grabe, S., Dolan-Pascoe, B., Twenge, J. M., Wells, B. E., & Maitino, A. (2009). Gender differences in domain-specific self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 34-45.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Greenberg, J. & Baron, R. A. (2008). Behavior in Organizations (Ninth Edition). Upper Saddle River: New Jersey, Pearson Prentice Hall.

Harter, S. (1993). Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in children and adolescents. In Self-esteem (pp. 87-116). Springer, Boston, MA.

Hull, K. E. (1999). The paradox of the contended female lawyer. Law & Soc'y Rev., 33, 687.

James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology. New York: Henry Holt.

Kaiser, L. C. (2007). Gender-job satisfaction differences across Europe: An indicator for labour market modernization. International Journal of Manpower, 28(1), 75-94.

Kling, K. C., Hyde, J. S., Showers, C. J., & Buswell, B. N. (1999). Gender differences in self-esteem: a meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 125(4), 470.

Ku, H., & Salmon, T. C. (2012). The incentive effects of inequality: An experimental investigation. Southern Economic Journal, 79(1), 46-70.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Long, A. (2005). Happily, ever after? A study of job satisfaction in Australia. Economic Record, 81(255), 303-321.

Major, B., Barr, L., Zubek, J., & Babey, S. H. (1999). Gender and self-esteem: A meta-analysis.

Marsh, H. W., & Craven, R. G. (2006). Reciprocal effects of self-concept and performance from a multidimensional perspective: Beyond seductive pleasure and unidimensional perspectives. Perspectives on psychological science, 1(2), 133-163.

Morrison, D. C., & Ryan, J. L. (1987). Endotoxins and disease mechanisms. Annual review of medicine, 38(1), 417-432.

Mruk, C. J. (2013). Self-esteem and positive psychology: Research, theory, and practice. Springer Publishing Company.

Mueller, C. W., & Wallace, J. E. (1996). Justice and the paradox of the contented female worker. Social Psychology Quarterly, 338-349.

Okpara, J. O., Squillace, M., & Erondu, E. A. (2005). Gender differences and job satisfaction: a study of university teachers in the United States. Women in management Review, 20(3), 177-190.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Panteli, A., Stack, J., Atkinson, M., & Ramsay, H. (1999). The status of women in the UK IT industry: an empirical study. European Journal of Information Systems, 8(3), 170-182.

Phelan, J. (1994). The paradox of the contented female worker: An assessment of alternative explanations. Social psychology quarterly, 95-107.

Porter, L. W., Lawler, E. E., & Hackman, J. R. (1975). Behavior in organizations.

Redmond, P., & McGuinness, S. (2019). The gender wage gap in Europe: Job preferences, gender convergence and distributional effects. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 81(3), 564-587.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures package, 61(52), 18.

Ryan, D. S. (1983). Self-esteem: An operational definition and ethical analysis. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 11(4), 295-302.

Sloane, P. J., & Williams, H. (2000). Job satisfaction, comparison earnings, and gender. Labour, 14(3), 473-502.

Sousa-Poza, A., & Sousa-Poza, A. A. (2000). Well-being at work: a cross-national analysis of the levels and determinants of job satisfaction. The journal of socio-economics, 29(6), 517-538.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sousa-Poza, A., & Sousa-Poza, A. A. (2003). Gender differences in job satisfaction in Great Britain, 1991–2000: permanent or transitory?. Applied Economics Letters, 10(11), 691-694.

Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel psychology, 46(2), 259-293.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2001). Age and birth cohort differences in self-esteem: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Personality and social psychology review, 5(4), 321-344.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Weinberger, C. J. (1998). Race and gender wage gaps in the market for recent college graduates. Industrial Relations: a journal of economy and society, 37(1), 67-84.

World Economic Forum (2018). The global gender gap report 2016. Geneva: Centre for the New Economy and Society.

Received: 25-Oct-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15370; Editor assigned: 26-Oct-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-15370(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Nov-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-15370; Revised: 26-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15370(R); Published: 19-Dec-2024