Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

Legal Challenges of Musharakah Mutanaqisah as an Alternative for Property Financing in Malaysia

Mohd Zakhiri Md Nor, School of Law, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Ani Munirah Mohamad, School of Law, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Alias Azhar, School of Law, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Hairuddin Megat Latif, School of Law, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Al-Hanisham Mohd Khalid, School of Law, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Yuhanif Yusof, School of Law, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abstract

Diminishing partnership or Musharakah Mutanaqisah (MM) is one of the underlying contracts adopted by Islamic financial institutions particularly for its property financing instruments. However, the implementation of MM in Malaysia has been surrounded with numerous legal challenges. Engaging in socio-legal approach, this study embarked upon the main objective of identifying the legal challenges surrounding the implementation of MM in Malaysia. Investigation was conducted involving three units of analysis: an Islamic bank, a legal firm, and an educational institution. Relevant parties were identified to be interviewed: a Shariah committee of the Islamic bank, a solicitor attending to the MM legal documentation and an academician teaching Islamic finance courses at the educational institution. The instrument employed was semi-structured interviews particularly to investigate the legal challenges of MM as an alternative for property financing in Malaysia. The findings revealed that there are numerous legal issues in the implementation of the MM in Malaysia, such as legal ownership of the MM property, major maintenance and repairs, restrictions imposed by the Malaysian laws and the duties and responsibilities of the MM partners i.e. the bank and the customer. In essence, the study is expected to contribute to the body of knowledge and serve as a guide for the policy makers in refining and improving the current process and procedure of MM contract as one of the preferred property finance products in Malaysia.

Keywords

Legal Challenges, Musharakah Mutanaqisah, Property Financing, Islamic Finance.

Introduction

The property development sector is one of the leading wealth management sectors in the world. Waqf and Islamic financing plays a crucial role towards this property development. Over the years, Islamic banking and finance products develop robustly in many parts of the world as the preferred method of financing the property development and acquisition. Islamic finance booms in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Pakistan, Sudan and United Kingdom (Samers & Lai, 2016). In Malaysia, one of the Islamic contracts used for property financing products is diminishing partnership or Musharakah Mutanaqisah (MM) which was first introduced by Kuwait Finance House Malaysia Berhad in the year 2005, followed by other financial institutions such as Maybank Islamic and RHB Islamic Bank.

Although MM theoretically seems to be a great alternative for property financing in Malaysia, for both retail and commercial contexts, its implementation has been quite problematic. At least two legal issues could be derived from the above practices. The first major problem in the implementation of MM in Malaysia is the legal restrictions imposed by the laws of Malaysia (Subky et al., 2017). Some of the restrictions are the National Land Code 1965 with regards to foreign ownership of properties, or the legal requirement to obtain the state authority’s consent for dealings involving specified properties, as well as the Foreign Investment Committee’s recommendation with regards to foreign ownership in corporations (in this case, the MM partnerships) or the investment by the bank of the customer, in cases where the bank and/or the customer is foreign within the meanings of the Malaysian laws (Asadov et al., 2018).

Secondly, the problem concerns the financing of properties under construction (Sabri & Ahmad, 2014). Because property financing for uncompleted assets are subject to legal and operation risks, such as the determination of rights and obligations of the parties, the transfer of property from the developer to the MM partnership, the commencement of the ‘diminishing’ portion of the shares from the bank to be acquired by the customer, also the risk of the projects being uncompleted and the like (Abdul-Razak & Amin, 2013). Hence, this is highly pertinent to be examined because of the legal issues and risks which might arise from the signing of MM arrangement between the bank and the customer for properties under construction. Accordingly, this study seeks to examine the legal challenges surrounding the implementation of MM as an alternative for property financing in Malaysia. Hopefully, this paper would provide insights to the legal problems and issues facing the implementation of MM in Malaysia.

Conceptualizing MM as an Alternative for Property Financing in Selected Jurisdictions

According to the MM operational terms, the bank and the customer participate either in the joint ownership of a property or an equipment, or in a joint commercial enterprise. The share of the bank is further divided into a number of units and it is understood that the customer will purchase the units of the share of the bank one by one periodically, thus increasing his own share till all the units of the bank are purchased by him so as to make him the sole owner of the property, or the MM venture, as the case may be (Shahwan et al., 2013; Arshad & Ismail, 2010).

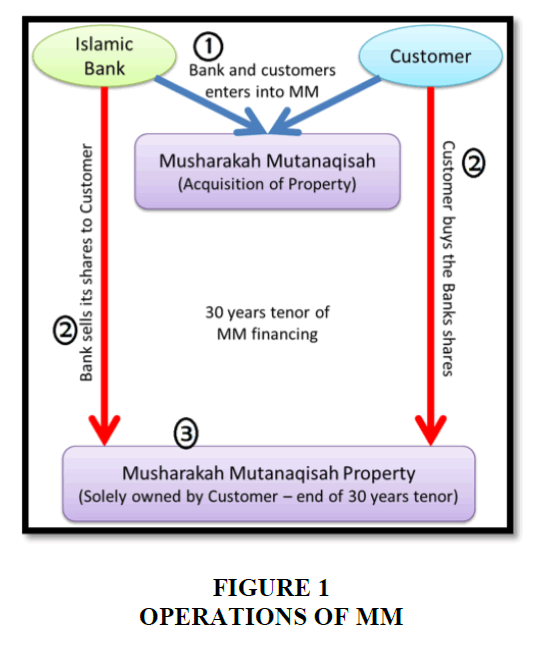

Accordingly, there are three major steps of MM operations, as produced in Figure 1:

1. Step 1: First, the Bank and the Customer enter into MM venture for the acquisition of the Property. At this stage, the MM legal documentation is executed between the Bank and the Customer to establish the MM venture, setting out the terms and conditions of the MM

2. Step 2: Throughout the tenor of the MM financing, the Customer gradually buys the Bank’s shares thus increasing his shares, while the Bank’s share diminishes.

3. Step 3: At this step, at the end of the tenor of the financing, the Customer would have completely purchased all the shares of the Bank in the MM venture, hence solely owning 100% of the MM Property.

In this regard, the position in Malaysia is that a number of local and foreign banks and financial institutions in Malaysia offer MM as one of their respective property financing products to attract a wide array of customers, both locally and internationally, and both Muslims and non-Muslims (Osmani & Abdullah, 2010).

Perhaps one of the earliest jurisdictions in the world to offer MM property financing is Pakistan. The operations of MM by Meezan Bank was elaborated by Usmani (2002) covering the MM characteristics in few Islamic banks in Pakistan. This product is called “Easy” home financing and the financing amount is 85% as equity party participation on behalf of the bank. Further comparison indicates that its modus operandi is close to Malaysian practices of MM (Meera et al., 2005). Additionally, Usmani (2002) also explained the MM financing for property as well as commercial banking.

Apart from that, profit and loss sharing financing strategies such as MM is also used as the underlying contract for Islamic property financing in various other jurisdictions such as Sudan (Saad & Razak, 2013). MM attracts quite a large portfolio for both retail and commercial financing by the Islamic banks in Sudan (Mikail & Rani, 2016).

Research Approach And Data Analysis

This research engaged upon socio-legal approach, hence the scope of the research largely involved examination of legal sources, both primary and secondary sources of written laws and decided cases, as well as journal articles, legal textbooks, reference materials and reports from respective banks which offer MM as one of its property financing products. As for the scope, the jurisdictional setting of this research was predominantly Malaysian context, with reference to other countries as a benchmark on the implementation of MM by its banks and financial institutions, such as Pakistan and Sudan. The purpose of setting this benchmark was for learning lessons from their experience in implementing MM in their respective countries and for suggesting improvements to the Malaysian context.

This research embarked upon two stages of research, the first stage was the formulation of the conceptual and theoretical understanding of the implementation of MM in Malaysia and other selected jurisdictions. The data sources for this stage was entirely library-based, which consisted both primary and secondary sources, such as laws and cases, academic articles, textbooks. The second stage of the research involved primary data collection from fieldwork in the form of case study design. Three units of analysis were involved in the data collection stage: a bank which offers MM as one of its property financing products, a legal firm which prepares the MM legal documentation and an academic institution of Islamic finance. The instrument employed for the data collection was semi-structured interviews involving respondents from each unit of analysis, being individuals who are knowledgeable and familiar with the legal provisions and the operations of MM as a property financing mechanism., being a Shariah committee of the Islamic bank, a solicitor attending to the MM legal documentation and an academician teaching Islamic finance courses at the educational institution.

The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed for analysis purposes. The interviews largely focused on the sample legal documentation for MM for property financing by the chosen Islamic bank for the study. The analysis method employed in this study was thematic analysis based on the predetermined themes of the study, engaging in both deductive and inductive approaches (Aronson, 1995; Guest et al., 2011). By adopting this approach, the researcher was able to witness the pattern of discussion by the interview respondents guided upon the themes relevant for the study. The finding of the analysis is produced in the following section.

Legal Challenges Surrounding the Implementation of MM as an Alternative for Property Financing in Malaysia

This part deliberates the empirical data generated from the examination of the legal documents as well as the interviews data pertaining the various legal challenges surrounding the implementation of MM as an alternative for property financing in Malaysia.

Building the Blocks of the Legal Documentation

Probably the most important aspect of MM arrangement would be the legal documentation which essentially encapsulates the intention of the MM parties’ right from the formation of the MM, through the continuation of the MM venture up until the dissolution of the arrangement. However, the challenge comes when it was actually the term sheet drafted by the bank and accepted by the customers, but the legal agreements are drafted by the solicitors attending to the MM contract (Haneef, 2011). Very often, these solicitors are panel lawyers of the bank. With the increasing demands of the MM financing facility by Islamic banks in Malaysia, various legal firms are engaged by the banks to actually draw up these agreements; each and every one of them is expected to attend to the building blocks of the legal documentation properly in order to capture the true and accurate intention of the MM parties. In cases where the bank has a set of standard legal documents, then the solicitors would be required to adopt these standards, leaving little room for improvisation based on the needs of each case.

Legal Ownership of the MM Property

Another legal issue would be the determination of the legal ownership of the MM property. It is a truism that the MM partners actually own the property, and this is known as beneficial ownership of the property. This essentially means that the MM partners are the ones who own the benefits under the property. However, the issue now arises as who should hold the legal ownership of the property, i.e., the person who is registered on the title of the property. This inherently becomes an issue because the Malaysian land law adopts the “torrens system”, which means “system by registration”. Accordingly, the name who is registered on the title as owner is the actual owner of the property and no one else.

The study found that there are various approaches used by the Islamic banks in order to record the names of the registered owner at the land offices in Malaysia. Some banks would prefer to have their own names registered on the title as the owner, whilst some other banks would prefer to maintain the names of the customers on the title. In any event, this in fact does not capture the true intention of the MM that the property is actually co-owned by the MM partners (Nor et al., 2017). To make things even more complicated, the diminishing nature of an MM contract would actually cause the percentage of the ownership of shares in the property fluctuate upwards and downwards, which would make the legal ownership of the property even more difficult to be captured into the land registration system.

Properties under Construction

Properties under construction would be accepted to be financed under MM financing facility. However, its implementation raises a number of legal issues, particularly to the diminishing part of the MM arrangement, which sale and purchase of shares in the property can only be affected once the property is completed. The Shariah prohibits the sale and purchase of shares in property if the property is still not existence, or shall we say, if the property is still under construction. Even bigger complication would arise in cases of abandoned housing projects, or problematic projects, where the construction could not be completed within the agreed duration. In such cases, MM would fail as no sale and purchase of shares can take place if the said property is not complete (Hanafi, 2012).

Data from the interviews revealed that in order to overcome this situation, the Islamic banks would execute a particular contract during the construction of the property, called contract for forward lease “Ijarah mausufah bil-zimmah”, which essentially means lease on the benefits of the property, and normally executed when the construction of the property is not yet completed. During the continuation of the lease contract, the customer would only be servicing the profit element under the financing facility, until the completion of the property.

MM Partner who is Foreign Entity/Individual

In some situations, the MM partner would be a foreign entity or an individual, for instance an Islamic bank in Malaysia which offers MM financing, or a foreign customer in need of property financing from a local Islamic bank. According to the Malaysian land laws, foreign interest in the form of foreign entity or individuals are restricted under Part 433B of the National Land Code 1956 from holding any interest in a local land, subject to the consent by the State Land Authority in the respective State. Therefore, it has become a legal obstacle for foreign Islamic banks or customers to deal with property intended to be financed under an MM arrangement.

The interview respondents reported that in such situations, the Bank would submit individual applications to the State Land Authority seeking consent to the foreign interest in the property. This legal problem, albeit not generalized to the entire population of the MM cases in Malaysia, still poses as a legal risk in the implementation of MM in Malaysia. Since this legal problem is localized to the Malaysian context, no lesson could be learned from the legal position in other jurisdictions.

MM Property is subjected to Malay-Reserved Status

Sometimes, the property intended to be used under the MM arrangement is subjected to Malay-reserved status. This means that the property can only be owned, and therefore registered, in the name of Malay. This is provided under the Malay-Reserved Enactments of each and individual states in Malaysia. Therefore, a problem will arise particularly because the MM venture itself is the beneficial owner of the property, even though the property is registered solely in the name of the Malay customer.

The legal position in Malaysia is that, the Banks would apply to the State authority to add their organizational status be recorded as a ‘Malay’ under the respective Malay-Reserved Enactments. At the moment, most States in Malaysia recognize a few Islamic banks as being Malay within the definition of the enactments, such as Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad, Bank Muamalat and a few other Islamic banks. And this is seen as an improvement to the problem of having MM property which is subjected to Malay-reserved status.

Maintenance and Major Repairs to the MM Property

Another legal issue arising surrounding the MM financing facility is the maintenance and major repairs to the MM property. Minor repairs are clearly within the responsibilities of the occupant of the property i.e. the customer, however, under the Shariah, the maintenance and major repairs should be borne by the MM partners together, as they are co-owners of the MM property. It is not right for the bank, albeit a financier from the perspective of MM being a financing facility, to pass on all the maintenance and major repairs to the customer alone (Azli et al., 2011).

In this situation, data from the study highlighted that some banks would clearly state in its legal documentation that the maintenance and major repairs would be borne by the MM partners instead of the customer alone. However, at the moment, this is not the case for many other Islamic bank which still treats MM as a financing facility hence still impose upon the customer to bear all the costs.

Conclusion And Way Forward For Implementing Mm As A Property Financing Product In Malaysia

The study found numerous legal concerns in the implementation of MM as a property financing product in Malaysia. Among others, legal concerns relate to the legal documentation of the MM arrangement, the issue of legal ownership of the MM property, legal concerns of properties under construction, legal restrictions in cases where one or both of the MM partners is a foreign legal/entity, the issue of MM property being subjected to Malays-reserved status, and finally the legal issue concerning maintenance and major repairs to the MM property.

Consequentially, it is here by submitted that the relevant authorities should improve the legal framework in terms of the Islamic finance implementation generally, and particularly on the issues of ownership of the MM property under Malay-reserved statuses as well as foreign ownership of the MM properties. The legal hiccups elaborated in the earlier sections of this paper indicate the urgent need to reform the various laws which hamper the smooth implementation of MM as an alternative for property financing in Malaysia. Apart from that, it is also suggested that improvements be made to the legal documentation pertaining to maintenance and major repairs to the MM property so that it would shed clarity to the rights and liabilities of the MM partners.

Based on the above, it could be concluded that this study is significant in the sense that the findings of this research would contribute to the body of literature on Islamic finance governance in general, and the implementation of MM in Malaysia particularly. It is suggested that MM Model could be adopted in waqf and property development. These possibilities need to be explored as a direction for future research.

Acknowledgment

This research is funded by Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) of the Ministry of Education, Malaysia. S/O Code: 14211.

References

- Abdul-Razak, D., & Amin, H. (2013). Application of musharakah mutanaqisah home financing as an alternative to traditional debt financing: Lessons learned from the US 2007 subprime crisis.Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance,9(3), 115-130.

- Aronson, J. (1995). A pragmatic view of thematic analysis.The qualitative report,2(1), 1-3.

- Arshad, N.C., & Ismail, A.G. (2010). Shariah parameters for Musharakah Contract: A comment.International Journal of Business and Social Science,1(1), 145-162.

- Asadov, A., Muhamad, S.Z.B., Ramadilli, S., Anwer, Z., & Shamsudheen, S.V. (2018). Musharakah Mutanaqisah home financing: issues in practice.Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research,9(1), 91-103.

- Azli, R.M., Othman, R., Sahri, M., Aris, N.A., Arshad, R., & Yaakob, A.R. (2011). Implementation of Maqasid Shari’ah in Islamic house financing: A study of the rights and responsibilities of contracting parties in Bai’Bithaman Ajil and Musharakah Mutanaqisah.Journal of Applied Business Research,27(5), 85-96.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M., & Namey, E.E. (2011).Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications.

- Hanafi, H. (2012).Critical perspectives on Musharakah Mutanaqisah home financing in Malaysia: Exploring legal, regulative and financial challenges. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Durham University.

- Haneef, R. (2011). Musharakah Mutanaqisah and legal issues: Case study of Malaysia.ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance,3(1), 93-124.

- Meera, M., Ahmad, K., & Razak, D. (2005). Islamic home financing through musharakah mutanaqisah and bay bithaman ajil contracts: A comparative analysis. Review of Islamic Economics, 9(2), 5-30

- Mikail, S.A., & Rani, M.S.M. (2016). Shar??ah contracts underpinning Mush?rakah Mutan?qi?ah financing: A conceptual analysis. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance, 8(1), 35-52.

- Nor, M.Z., Dahlan, N.H.M., Azhar, A., Khalid, A.H.M., & Mohamad, A.M. (2017). Challenges affecting the adjudication of Islamic finance cases in the Malaysian courts.Advanced Science Letters,23(8), 7923-7926.

- Osmani, N.M., & Abdullah, M.F. (2010). Musharakah mutanaqisah home financing: A review of literatures and practices of Islamic banks in Malaysia.International Review of Business Research Papers,6(2), 272-282.

- Saad, N.M., & Razak, D.A. (2013). Towards an application of Musharakah Mutanaqisah principle in Islamic microfinance.International Journal of Business & Society,14(2), 48-63.

- Sabri, S.R.M., & Ahmad, F.S. (2014). The behaviour of profit of Musharakah Mutanaqisah partnership home ownership by the case of abandoned housing project. InAIP Conference Proceedings(pp. 1067-1072).

- Samers, M., & Lai, K. (2016). Conceptualizing Islamic banking and finance in Malaysia and Singapore: Conventional rule regimes, National forms of governance and Islamic financial architectures. Retrieved August 10, from, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2767357

- Shahwan, S., Mohammad, M.O., & Rahman, Z.A. (2013). Home financing pricing issues in the Bay’Bithaman Ajil (BBA) and Musharakah Mutanaqisah (MMP).Global Journal Al-Thaqafah,3(2), 23-36.

- Subky, K.H.M., Liu, J.Y., Abdullah, M.M., Mokhtar, Z.F., & Faizrakhman, A. (2017). The implication of Musharakah Mutanaqisah in Malaysian Islamic Banking Arena: A perspective on legal documentation.International Journal of Management and Applied Research,4(1), 17-30.