Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

Learning Orientation, Access to Debt Finance, Organizational Capability and Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises: A Proposed Model

Samson Waibe Bature, Federal College of Education Gusau, Universiti Utara, Malaysia

Mohd Sallehuddin Rasdan, Universiti Utara, Malaysia

Cheng Wei Hin, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abstract

In the 21th century’s business environment, no business firm takes a lackadaisical approach to the marketplace and expect to succeed given the increasing global complexity and stiff competition among firms. The purpose of this study is to come up with some strategic action plans that may equip small and medium enterprises (SMEs) with the required broad capabilities to cope in the marketplace. Based on extant literature, and dynamic capability view, we propose that availability of external finance will enhance the positive relationship between learning orientation and organizational capability which may in turn lead to superior performance of SMEs in emerging economies. Empirical investigation on the proposed framework may give an in-depth insight pertains to the role of learning orientation in firm performance. Also, it will benefit SME owners/managers to imbibe the spirit of continuous learning to develop a broad base capability to keep abreast with rapid changes in the business environment.

Keywords

Learning Orientation, Access to Debt Finance, Organizational Capability, SME Performance.

Introduction

Today’s business environment is characterized by rapid technological changes and stiff competition. This means that no business enterprise takes an ad-hoc approach to the marketplace and expects to outperform others. Thus, to perform excellently in a dynamic business environment, firms must update their technical know-how in accordance with the changing business environment. Specifically, business firms in the category of small and medium enterprise whose role in promoting the development of local technology is pronounced must rise to the occasion to deliver well in the market (Rua et al., 2018). Although small and medium enterprises (SMEs) constitute majority of business establishments worldwide, evidence indicates that SMEs in some parts of the world perform better while in others they do not. For instance, SMEs in developed economies such as UK and US are regarded as the strong pillar for economic growth because they constitute about 99 percent of business establishments, employ an average of 70 percent of workforce as well as roughly generate between 50 and 60 percent of value added to various economies Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2017. Also, the report states that SMEs contribute about 45 and 33 percent to total employment and GDP, respectively in countries like India, Colombia, and Viet Nam which are regarded as emerging economies.

It is evident that the contribution of SMEs with reference to jobs creation and GDP in emerging economies is low compared to their counterparts in developed economies. In the literature, prominent among the reasons for low contribution of SMEs to national growth in emerging economies, is gross inadequacy of infrastructural facilities (Selomon, et al., 2016; Vij & Bedi, 2016), as well as resource constraint features of SMEs (Lechner & Gudmunsson, 2014; OECD, 2017; Mikalef et al., 2015; Rua et al., 2018). For instance, resource challenges include poor managerial skills, inability to adapt to technological sophistication (OECD, 2017), and inadequate access to finance (Mikalef et al., 2015).

Against this backdrop, Maes and Sels (2014), as well as OECD (2017) suggested that SME owners/managers, employees or firms in general must develop ability to update their knowledge, skills or know-how to keep abreast with technology advancement in their business environment to enhance sustainable superior performance. Therefore, we advocate that learning orientation (LO) might offer business firm’s ability to create required knowledge, skills or knowhow to adapt easily to technological changes in their business environment because Barkat and Beh (2018) found that intellectual capital has strong influence on organizational capability of knowledge creation and firm performance. Also, Lee et al. (2014) argue that LO is one of the most important components of strategic orientations in strategic management literature that permits firms to create and use knowledge.

LO is described as a firm’s predisposition to knowledge creation and utilization with the aim of gaining competitive advantage (Sinkula et al., 1997). In other words, Hakala (2013) viewed LO as courses of action that influence the behaviour of members of organization through knowledge creation or acquisition to change processes and job descriptions that is probably supportive to the firm’s objectives of delivering superior value. Given the definitions of LO, it is not only important, but it is necessary for business firms to invest significantly in learning orientation to acquire organizational capability and succeed in the marketplace. However, to develop the required abilities that could warrant SMEs to acquire the needed knowledge, skills or know-how may be costly because several studies have observed that SMEs suffer huge resource limitations (OECD, 2017; Mikalef et al., 2015; Rua et al., 2018). Thus, drawing from dynamic capability theory (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997), we argue that a configuration and integration of LO with access to debt finance as an external factor from the economic domain would build organizational capability to allow SMEs perform well in the face of rapid changes in technology.

Although LO study is mostly associated with firm performance as a main dependent variable (Wolff et al., 2015; Kaya and Patton, 2011) view LO as a strategic posture used by firms to alter long time held process, procedure, and practice to embrace novel techniques, processes and methods to create knowledge. From the afore-mentioned, we argue that LO is a veritable resource that brings about organizational capability which in turn affects firm performance. However, there is dearth of research on LO as a dimension of strategic orientation compared to others like entrepreneurial orientation in the literature. Despite that, majority of the existing studies on LO, concentrate mostly on LO-firm performance relationship. Thereby ignoring the role of LO in developing organizational capability which in turn serve as key determinant of superior firm performance. Consequently, we proposed that organizational capability would serve as a mechanism through which LO impact firm performance. Also, we envisaged that access to debt finance would enhance the role of LO in building diverse organizational capability to enable SMEs face the rapidly changing business environment. To cap it all, the presumptions are premised on the theory of dynamic capability which implies that SMEs need to effectively scout, integrate and reconfigure resources with strategies and capabilities to develop diverse capabilities that could lead to superior performance in a dynamic business environment (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997).

The section that follows is theoretical background and conceptual framework which linked LO and access to debt finance with organizational capability, as well as the relationship between organizational capability and firm performance. This is then followed by a description of the methodological process to achieve the objectives of the study and lastly, conclusion.

Theoretical Background And Conceptual Framework

Dynamic Capabilities Theory

DCV supposes that in a rapidly dynamic business environment, excellent business performance relies on strength of the firm to constantly alter resources, strategies and capabilities in way and manner that best suits the changing business environment (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997). The significance of DCV perspective in the proposed study, is that since today’s business environment is highly competitive and dynamic, it is required of business firms to acquire, deploy and continuously upgrade their knowledge-base, skills, know-how or capabilities to secure competitive edge and better performance in the market. Besides, Li and Liu (2014) observed that the DCV perspective is still emerging thus strongly suggested its application in developing economies. Furthermore, the theory portrays the notion that respective resource of an enterprise constitutes a variety of assets for such enterprise (Grant, 2002), but these assets may not add significant value to the enterprise without broad capabilities to skilfully alter them towards achieving competitive advantage of quality products/services.

Consequently, we state that the capacity of enterprise to reconfigure/transform resources to address or cope with challenges of dynamic market environment largely depend on the ability of such enterprise to create knowledge or acquire knowledge and use knowledge to further boost its skills and technical know-how in the direction that could support the firm’s activities to deliver superior value.

Firm Performance

Firm performance is often referred to the overall health of the enterprise expressed in relative to the output of efforts or activities carried out to meet the expectation of stakeholders as well as its general objectives (Agwu, 2018). It is the yardstick to evaluate the level of resource utilization, achieved results as compared to stated business goals (Vij & Farooq, 2015). Extant literature shows that the debate as to the best approach to measure business performance is still far from been conclusive (Odumeru, 2013; Gupta & Wales, 2017; Rauch et al., 2009). Scholars such as Gupta and Batra (2016) argue that objective measures of business performance are mostly seen by SMEs owners/managers as private information, as such are treated as confidential information. Against this background, they suggested that subjective measurement approach is most appropriate to measure business performance of SMEs. On the contrary, Gupta and Wales (2017) contend that the suitable method to assess business performance is objective measurement approach which relies on published data about the enterprise.

Notwithstanding, Gnizy et al. (2014) postulate that in terms of dependability or reliability, both objective and subjective measures of business performance are almost the same. As stated earlier, researcher often faced challenges to collate data for objective performance measurement most especially when the study involves performance of small businesses (Gupta & Batra, 2016). In addition, most business enterprises tend to be more pleased and willing to express their subjective perception concerning their performance than to provide objective data (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). Therefore, it may be appropriate to adopt subjective measures of performance to empirically test this proposed framework.

Learning Orientation

The concept of LO is often associated with Sinkula et al. (1997) as pioneers. They view LO as organizational philosophy that create and use knowledge to promote competitiveness. According to Wolff et al. (2015), LO entails a set of ideals that are designed toward learning. To Kaya and Patton (2011), LO is viewed as a culture that enable firms to continuously question long term held beliefs, practices, principles or traditions about the way and manner which firm is operated, promote the firm’s knowledge base which in turn abet the firm to create understanding, competences to respond better to changing business environment. Thus, a strategic posture toward learning philosophy gives the ability to create new knowledge that allow for effective coordination, combination and configuration of the entire firm’s resources to achieve business objectives.

LO as one of the basic components of organizational learning, has been widely conceptualized to comprise of three dimensions namely, commitment to learning, openmindedness, and shared vision or purpose (Sinkula et al., 1997). Commitment to learning indicates the readiness or willingness of the organization to emphasize and encourage activities that promote learning within and outside of its premises. Open-mindedness entails the firm’s policy, principle or regulation in relation to receptiveness to novel ideas or initiatives. While shared vision is a behavioural concept, which emphasizes a common front to spread information that could have positive impact on the firm’s knowledge base and subsequently renew the routine operational system and capabilities to address changing market needs. Although Calantone et al. (2002) advocated for inclusion of intra-organizational knowledge sharing (i.e., learning among varied functional units within an enterprise) as a component of LO, Nhon, Thong, and Van Phuong (2018) observed that organizational structure of SMEs is less hierarchical in nature. In the light of this observation, intra-organizational knowledge sharing may not be suitably applicable in this context. Therefore, it may be appropriate to measure LO as a composite construct in terms of firm’s commitment to learning, open-mindedness, and shared vision. This parameter might clearly show how SMEs create and use skills, knowledge, and technical knowhow to wield robust capabilities to deliver superior performance.

Access to Debt Finance

Access to debt finance as described by Ganbold (2008) means the situation where financial and non-financial hitches create a little or no significant threat to the acquisition of financial resources and services. Put differently, Kelley et al. (2012) viewed access to debt finance as the sufficiency of externally sourced financial resources which could include capital and other form of financial services to business enterprises. Having access to finance is crucial to the growth and development of any form of business establishment (Kasseeah et al., 2013). However, it is obvious in the literature that financial accessibility is one of the major challenges confronting SMEs across several national boundaries, especially in emerging economies (OECD, 2017; Singer et al., 2015). The implication is that access to financial resources might have significant influence on the firm’s effort to build diverse capabilities to deliver superior performance. This notion lends support to the views of Tang et al. (2008) that business firms may not successfully implement their strategic intentions or action plans without adequate financial resources.

In addition, Elsenhardt and Martin (2000), and Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) stress that the capacity to grasp and utilize any opportunities in the marketplace largely depends on the financial strength of business enterprises to purchase both tangible and intangible resources. Nevertheless, Fatoki (2012) opined that business firms with relatively high level of financial leverage might be in better position to deliver superior value in the marketplace. Thus, access to debt finance is seen as a dependable factor which business enterprises rely upon to support their capabilities to identify and seize opportunities to deliver value in the marketplace. Consistent with Kelley et al. (2012), access to debt finance may be gauged on the availability and accessibility of loan from financial institutions, friends/family; trade credit from suppliers or other business partners/associates; equipment leasing by either government or its agencies, suppliers, and other SME supporting agencies.

Organizational capability

Organizational capability involves a whole range of business activities that could permit a firm to achieve competitive edge over rivals to perform better in the marketplace (Winter, 2003). In other words, organizational capability is the capacity of an enterprise to develop a befitting structure with respect to administrative, operational or routine procedures and activities tilted toward achieving a common goal (Guan & Ma, 2003). To Ho et al. (2016), organizational capability expresses the ability of an enterprise to assemble and integrate resources from various sources for optimal usage to deliver superior performance. This implies that capabilities are pivotal not only to business enterprises but to the success of all forms of establishment because in the end, organizational capability serve as mechanism that bridges the gap between a firm’s present and future performance.

The term organizational capability can be seen from different view point probably based on contextual meaning or purpose to be achieved (Rodríguez-Gutiérrez et al., 2015). For instance, at one point or the other different studies had categorized organizational capability as innovation capability, managerial capability, marketing capability, business collaboration capability, production capability, research and development capability, technology capability, distribution capability, strategic capability (Acquaah & Agyapang, 2015). Not surprising Day (1994), as well as O'Regan, and Ghobadian (2004) viewed organizational capability as a complex concept, the list of which can go on continuously without end. Despite the categorization of organizational capability, it is important to recall that small enterprises particularly in emerging economies, are characterized by a very simple administrative structural setting (National Bureau for Statistics, 2013). Therefore, in its simplest meaning, organizational capability entails the capacity of small and medium enterprises to commit the scarce resources within their reach to deliver a value that is in line the prevailing market needs (McKelvie and Davidsson, 2009). In view of the above, the proposed study seeks to explore the extent to which organizational capability can be influenced by SMEs’ commitment to learning, receptiveness to initiatives or ideas (open-mindedness), and vision for dissemination of meaningful information (shared vision policy).

Learning Orientation and Organizational Capability

Extant literature argues that LO boosts organizational capabilities (Aragón-Correa et al., 2007; Calantone et al., 2002; Dulger et al., 2014, 2016). For instance, Aragón-Correa et al. (2007) reveal that learning stimulates deep thinking which generates novel ideas, thereby plays a central role in developing capabilities. Calantone et al. (2002) suggest LO implies the creation and utilization of new ideas and knowledge to improve organization’s practices, and processes/procedures which can bring about organizational capabilities to further synchronize firm’s resources to address market needs. Like Calantone et al. (2002), the studies conducted by Dulger et al. (2014, 2016) demonstrate positive effect of learning orientation on firms’ capability to innovate, which in turn had positive influence on firm performance. Similarly, the findings of Denford (2013) revealed that existing and renewed firm knowledge contributed in great amount to the integration and utilization of organizational capability that impacted superior performance.

Based on the foregoing arguments and postulations, it implies that business enterprises that emphasize much on learning orientation by way of showing commitment to learning, openmindedness, as well as shared vision, might accumulate, codify and articulate a wealth of knowledge resulting to diverse organizational capabilities to seize opportunity to serve divergent market demands better than other rivals in the market. This is much more in line with the postulations of Dynamic Capability View (DCV) which implies that constant integration, reconfiguration, renewal, as well as recreation of knowledge, skills or know-how in line with changing market environment will bring about competitive advantage and subsequently superior performance in the marketplace. Therefore, drawing from extant literature, as well as DCV perspective, a formidable learning philosophy in a business enterprise seems to be a critical factor to the development of organizational capability to cope with changes in the business environment. Thus, we make the following proposition:

Proposition 1: Learning orientation will relate positively with organizational capability.

The Potential Moderating Role of Access to Debt Finance on the Relationship between LO and SME Performance

The process of LO undertaken by firms for improved capabilities requires some financial commitments. However, given the resource constraints of SMEs as widely reported in the literature (Lechner & Gudmunsson, 2014; Rua et al., 2018), to be able to create the required organizational capability, SMEs might depend on external finance to effectively and efficiently integrate and reconfigure resources to accomplish their business goals (Helfat et al., 2007). Elsenhardt and Martin (2000), Tang et al. (2008), and Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) have stressed the relevance of access to financial resources in the implementation of any strategic postures. Moreover, Adomako et al. (2016) demonstrated that access to external finance is essential resource for building robust organizational capabilities which are prerequisite for indulging into various business undertakings to achieve superb performance. Therefore, it suggests that access to debt finance as an external essential resource, can complement LO in developing diverse capabilities for the firm to perform well in the marketplace. This view point finds support in DCV perspective which stressed that frequent configuration and/or reconfiguration of firm’s resources (both internal and external) and capabilities creates renewed capabilities to efficiently pursue and deliver a value that adequately addresses market needs arising from rapidly changing business environment. Hence, Within the rubric of DCV perspective, we develop a proposed framework to predict the interaction of access to debt finance with LO as a major source of organizational capability that is needed to keep abreast with technological changes in the business environment. Hence, the following research proposition is drawn:

Proposition 2: Access to debt finance will moderate the relationship between learning orientation and organizational capability. Specifically, the relationship will be stronger (more positive) when SMEs have better access to debt finance.

Organizational Capability and Firm Performance

Prior studies have acknowledged the influence of organizational capability on firm performance (Fong & Chang, 2012; O'Regan & Ghobadian, 2004; Rehman and Saeed, 2015; Tzokas et al., 2015; Yung & Tsai, 2016). For example, O'Regan and Ghobadian (2004) argue that firms who adopt effective strategic postures and effectively match such strategic postures with organizational resources and capabilities may experience superb performance. Fong and Chang (2012) modelled the link between proactive environmental innovation capability and firm performance. Empirical evidence revealed that innovation capability positively influenced firm performance. Also, the study conducted by Goh et al. (2012) report that high organizational learning capability which means high knowledge base, boost firm performance.

Tzokas et al. (2015) examine the effect of absorptive capability on performance of firms in South Korea. The report indicates that firm’s performance is largely determined by features of absorptive capability. Similarly, in a study of 473 industrial technology firms in Taiwan et al. (2016) indicate that organizational capabilities had significant influence on business performance. Furthermore, Rehman and Saeed (2015) find that superb and sustainable firm performance is dependent on dynamic capabilities. Indeed, this is in line with Teece et al. (1997) sustainable competitive advantage and brilliant performance in a dynamic environment might only be achieved via effective and efficient integration of strategic intentions, resources and capabilities, which is the central view point of dynamic capability theory. Therefore, we make the following proposition:

Proposition 3: Organizational capability will positively influence firms’ performance.

Organizational Capability as A Potential Mediator between LO and SME Performance

According to dynamic capability theory superior business performance comes from the proper integration and reconfiguration of strategies, resources, and capabilities to address target market’s needs or demands in a competitive and dynamic environment (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997). This implies that good alignment of strategic action plans with resources serves as a veritable source of organizational capabilities and capabilities in turn utilize strategic intentions and resources to achieve desired outcomes. In other words, strategic intentions and resources require organizational capability to generate significance for any business establishment and reconfiguration of all provides superior performance.

Learning orientation is regarded as one of the major sources of organizational knowledge-based, as well as key to organizational capabilities (Neill et al., 2014). Organizational capabilities are often associated with organizational knowledge-based to provide superior performance (Lin & Wu, 2014). The implication is that the mechanism by which learning orientation influence firm performance is that, initially learning orientation is transformed into organizational capability before it can impact on performance (Niell et al., 2014). Based on the tenets of DCV and prior studies, it is logical to suppose that organizational capability may serve as a potential mechanism through which LO indirectly improves SME performance. Hence, the following proposition:

Proposition 4: Organizational capability mediates the relationship between LO and SME performance.

Proposed Conceptual Framework

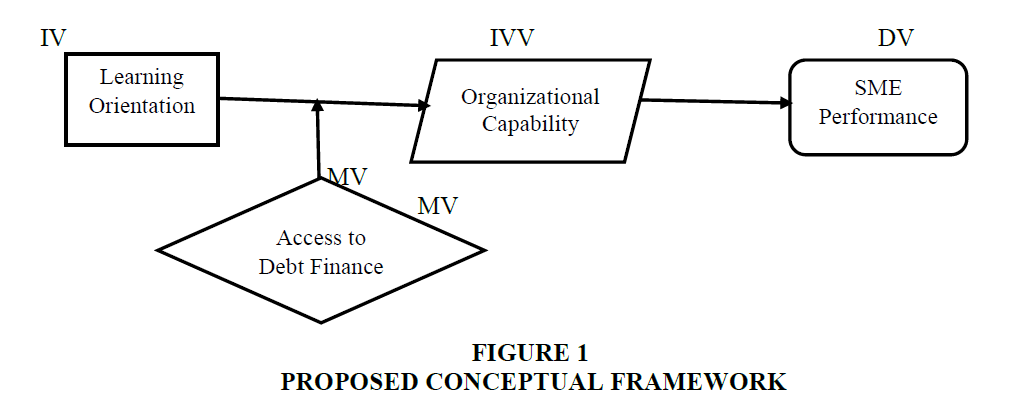

Drawing from the four research propositions made in this study, a proposed conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1 to depict the expected flow of relationships among the variables under study.

As shown in Figure 1:, learning orientation is regarded as independent variable (IV) and SME performance as dependent variable (DV). Also, access to debt finance is considered a potential moderating variable (MV) that may facilitate the implementation of learning activities in developing organizational capability which in turn might serve as intervening variable (IVV) in the relationship between learning orientation and SME performance. By so doing, the proposed model agrees with the dynamic capabilities view (DCV) of the firm.

Research Methodology

Basically, this study relied on extant literature and DCV to propose the relationship shown in Figure 1. Indeed, extant literature from varied scholarly data sources was sourced to make propositional statements subject to future empirical investigations.

Conclusion

It is pertinent to note that the researchers draw inspiration from the rubric of dynamic capability theory to propose the conceptual framework which seeks to evaluate the links among LO, access to debt finance, organizational capability, and SME performance. Specifically, we proposed that the relationship between LO and SME performance is better understood when it is viewed through an intervening mechanism such as organizational capability. Nonetheless, considering resource constraints of SMEs, especially financial resources, we equally suggest that if SMEs can raise or access substantial external financial resources, the impact of LO in building organizational capability might be higher and consequently lead to better firm performance. Therefore, this proposed conceptual framework would not only provide deeper understanding about the indirect role of LO in firm performance but would also reveal the eminence of availability of external financial resources in implementing firm’s strategic actions, as well as provide a practical illustration of dynamic capability theory in terms of its applications when it is empirically tested in emerging economies.

References

- Acquaah, M., & Agyapong, A. (2015). The relationship between competitive strategy and firm performance in micro and small businesses in Ghana: The moderating role of managerial and marketing capabilities.Africa Journal of Management,1(2), 172-193.

- Adomako, S., Danso, A., & Ofori Damoah, J. (2016). The moderating influence of financial literacy on the relationship between access to finance and firm growth in Ghana.Venture Capital, An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance,18(1), 43-61.

- Agwu, M.E. (2018). Analysis of the impact of strategic management on the business performance of SMEs in Nigeria.Academy of Strategic Management Journal,17(1), 1-20.

- Aragón-Correa, J.A., García-Morales, V.J., & Cordón-Pozo, E. (2007). Leadership and organizational learning's role on innovation and performance: Lessons from Spain.Industrial marketing management,36(3), 349-359.

- Barkat, W., & Beh, L.S. (2018). Impact of intellectual capital on organizational performance: evidence from a developing country.Academy of Strategic Management Journal,17(2), 1-8.

- Calantone, R.J., Cavusgil, S.T., & Zhao, Y. (2002). Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance.Industrial marketing management,31(6), 515-524.

- Day, G.S. (1994). The capabilities of market-driven organizations.Journal of marketing: A quarterly publication of the american marketing association,58(4), 37-52.

- Denford, J.S. (2013). Building knowledge: developing a knowledge-based dynamic capabilities typology. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(2), 175-194.

- Dulger, M., Alpay, G., Bodur, M., & Yilmaz, C. (2014). How do learning orientation and strategy yield innovativeness and superior firm performance?.South African Journal of Business Management,45(2), 35-50.

- Dulger, M., Alpay, G., Yilmaz, C., & Bodur, M. (2016). How does learning orientation generate product innovativeness and superior firm performance? The Business and Management Review,7(3), 68-77.

- Eisenhardt, K.M., & Martin, J.A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they?.Strategic management journal,21(10-11), 1105-1121.

- Fatoki, O. (2012). The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on access to debt finance and performance of small and medium enterprises in South Africa.Journal of social science,32(2), 121-131.

- Fong, C. M., & Chang, N. J. (2012). The impact of green learning orientation on proactive environmental innovation capability and firm performance.African Journal of Business Management,6(3), 727-735.

- Ganbold, B. (2008).Improving access to finance for SME: International good experiences and lessons for Mongolia(Vol. 438). Institute of Developing Economies.

- Gnizy, I., Baker, W.E., & Grinstein, A. (2014). Proactive learning culture: A dynamic capability and key success factor for SMEs entering foreign markets.International Marketing Review,31(5), 477-505.

- Goh, S.C., Elliott, C., & Quon, T.K. (2012). The relationship between learning capability and organizational performance: a meta-analytic examination.The learning organization,19(2), 92-108.

- Grant, R.M. (2002). Contemporary strategy analysis (4th Ediion). Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

- Guan, J., & Ma, N. (2003). Innovative capability and export performance of Chinese firms.Technovation,23(9), 737-747.

- Gupta, V.K., & Batra, S. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in Indian SMEs: Universal and contingency perspectives.International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship,34(5), 660-682.

- Gupta, V.K., & Wales, W.J. (2017). Assessing organisational performance within entrepreneurial orientation research: Where have we been and where can we go from here?The Journal of Entrepreneurship,26(1), 51-76.

- Hakala, H. (2013). Entrepreneurial and learning orientation: Effects on growth and profitability in the software sector.Baltic Journal of Management,8(1), 102-118.

- Helfat, C.E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D. & Winter, S. (2007). Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organisations. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Ho, T.C.F., Ahmad, N.H., & Ramayah, T. (2016). Competitive capabilities and business performance among manufacturing SMEs: Evidence from an emerging economy, Malaysia.Journal of Asia-Pacific Business,17(1), 37-58.

- Kasseeah, H., Ancharaz, V.D., & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V. (2013). Access to Financing as a Barrier to Trade: Evidence from Mauritius.Journal of African Business,14(3), 171-185.

- Kaya, N., & Patton, J. (2011). The effects of knowledge?based resources, market orientation and learning orientation on innovation performance: An empirical study of Turkish firms.Journal of International Development,23(2), 204-219.

- Kelley, D.J., Singer, S., & Herrington, M. (2012). The global entrepreneurship monitor.2011 Global Report, GEM 2011,7.

- Kumar, A. (2005). Measuring financial access through users’ surveys core concepts, questions and indicators. Washington DC and London.

- Lechner, C., & Gudmundsson, S.V. (2014). Entrepreneurial orientation, firm strategy and small firm performance.International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship,32(1), 36-60.

- Lee, D.H., Choi, S.B., & Kwak, W.J. (2014). The effects of four dimensions of strategic orientation on firm innovativeness and performance in emerging market small-and medium-size enterprises.Emerging Markets Finance and Trade,50(5), 78-96.

- Li, D.Y., & Liu, J. (2014). Dynamic capabilities, environmental dynamism, and competitive advantage: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2793-2799.

- Lin, Y., & Wu, L.Y. (2014). Exploring the role of dynamic capabilities in firm performance under the resource-based view framework.Journal of business research,67(3), 407-413.

- Maes, J., & Sels, L. (2014). SMEs' radical product innovation: the role of internally and externally oriented knowledge capabilities.Journal of Small Business Management,52(1), 141-163.

- McKelvie, A., & Davidsson, P. (2009). From resource base to dynamic capabilities: an investigation of new firms.British Journal of Management, 20(1), 63-80.

- Mikalef, P., Pateli, A., Batenburg, R.S., & van de Wetering, R. (2015). Purchasing alignment under multiple contingencies: a configuration theory approach.Industrial Management & Data Systems,115(4), 625-645.

- National Bureau for Statistics (2013). Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise National Survey 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/pdfuploads/MSME%20Presentation.pdf

- Neill, S., Singh, G., & Pathak, R.D. (2014). Technology and marketing capabilities in a developing economic context: Assessing the resource-based view within a boundary condition.International Journal of Business and Economics,13(1), 75-92.

- Nhon, H.T., Thong, B.Q., & Van Phuong, N. (2018). The Impact of Intellectual Capital Dimensions on Vietnamese Information Communication Technology Firm Performance: A Mediation Analysis of Human and Social Capital.Academy of Strategic Management Journal,17(1), 1-15.

- Odumeru, J. A. (2013). Innovation and organisational performance. Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 2(12), 1 8-22.

- OECD (2017) Enhancing the contributions of SMEs in a global and digitalised economy Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-8-EN.pdf

- O'Regan, N., & Ghobadian, A. (2004). The importance of capabilities for strategic direction and performance.Management Decision,42(2), 292-313.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G.T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future.Entrepreneurship theory and practice,33(3), 761-787.

- Rehman, K.U., & Saeed, Z. (2015). Impact of dynamic capabilities on firm performance: Moderating role of organizational competencies.Sukkur IBA Journal of Management and Business,2(2), 18-40.

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, M.J., Moreno, P., & Tejada, P. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation and performance of SMEs in the services industry.Journal of Organizational Change Management,28(2), 194-212.

- Rua, O., França, A., & Fernández Ortiz, R. (2018). Key drivers of SMEs export performance: the mediating effect of competitive advantage.Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(2), 257-279.

- Selomon, T.T., Urassa, G.C., & Allan, I.S. (2016). The effects of organisational capabilities on firm success: Evidence from Eritrean wood-and-metal-manufacturing firms.African Journal of Economic and Management Studies,7(3), 314-327.

- Singer, S., Amorós, J.E., & Arreola, D. M. (2015). Global entrepreneurship monitors 2014 global report.Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 1-116. Retrieved on March 27, 2018, from http://www.babson.edu/Academics/centers/blank-center/globalresearch/gem/Documents/GEM%202014% 20Global%20Report.pdf.

- Sinkula, J.M., Baker, W.E., & Noordewier, T. (1997). A framework for market-based organizational learning: Linking values, knowledge, and behavior.Journal of the academy of Marketing Science,25(4), 305-318.

- Tang, J., Tang, Z., Marino, L.D., Zhang, Y., & Li, Q. (2008). Exploring an inverted U?Shape relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance in Chinese ventures.Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 32(1), 219-239.

- Teece, D.J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management.Strategic Management Journal,18(7), 509-533.

- Tzokas, N., Kim, Y. A., Akbar, H., & Al-Dajani, H. (2015). Absorptive capacity and performance: The role of customer relationship and technological capabilities in high-tech SMEs.Industrial Marketing Management,47(1), 134-142.

- Vij, S., & Bedi, H.S. (2016). Effect of organisational and environmental factors on innovativeness and business performance relationship.International Journal of Innovation Management,20(03), 1-28.

- Vij, S., & Farooq, R. (2015). The Relationship Between Learning Orientation and Business Performance: Do Smaller Firms Gain More from Learning Orientation?IUP Journal of Knowledge Management,13(4), 7-28.

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach.Journal of business venturing,20(1), 71-91.

- Winter, S.G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities.Strategic management journal,24(10), 991-995.

- Wolff, J.A., Pett, T.L., & Ring, J.K. (2015). Small firm growth as a function of both learning orientation and entrepreneurial orientation: An empirical analysis.International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 21(5), 709-730.

- Yung, I.S., & Tsai, C.F. (2016). Product architecture and organisational capabilities' impact on performance: Taiwan's IT industry.International Journal of Information Technology and Management,15(3), 227-250.