Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 3

Leadership Lessons From the Diabolic Covid-19 Pandemic: Views of Utility SOE Senior Managers

Pramjeeth S, The IIE Varsity College & Graduate of UKZN

Mutambara E, Academic University of KwaZulu-Natal

Citation Information: Pramjeeth, S., & Mutambara, E. (2022). Leadership lessons from the diabolic covid-19 pandemic: Views of utility SOE senior managers. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(S3), 1-15.

Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has presented managers at both public and private organisations with an invaluable opportunity to reflect and reassess their leadership approaches as they begin to prepare to lead their team in the new world created by the pandemic. The study sought to examine the views of senior managers of a utility SoE in South Africa, Eskom, in as far as lessons learnt from the Covid-19 pandemic. Using a qualitative research design, the study surveyed 65 senior managers at Eskom using an online survey platform. The study established that the senior managers had learnt to be more empathetic, supportive towards their staff, and cared about their well-being. They had to learn to embrace the use of technology and increase their trust in their team as they worked from home. They found that they had to communicate and collaborate with their team more frequently and improved on the clarity and specificity of their communication while being more adaptable, agile, flexible and responsive as they responded to the challenges presented by the pandemic. Senior managers and their teams at SOEs need to embrace change, learn from it and adapt their leadership approaches to accommodate the changing environment.

Keywords

Covid-19, Eskom, Lessons, Leadership, Pandemic, Qualities, Senior Managers, SoE, South Africa, Traits, VUCA.

Introduction

When one thinks about state-owned enterprises (SoEs), notions of archaic entities that are complex, complicated and controlled by the government with its linear policies and regulations and conventional thinking and leadership approach that does not embrace change, neither adapt to the changing business environment easily. The covid-19 pandemic, a crisis of diabolic propor-tions, has disrupted leadership approaches, business models and crippled many public and pri-vate organisations worldwide. Although a catastrophic crisis of diabolical proportions, it can be viewed as an opportunity for senior managers to reassess their world views, their behaviours, strengths and weaknesses, business models, communication mediums and their role in society and organisations to re-strategize to embrace new thinking, business and leadership models, di-versity, engagement, presenting and the drive for excellence.

Thus, this study considers the views of senior managers at Eskom, a utility SoE on how the pandemic has changed their leadership approaches in so far as describing the lessons learnt from the Covid-19 pandemic, providing them with an opportunity to turn the possible desired future states at Eskom into reality.

In today’s climate, a crisis is inevitable. It is unknown when and how it will happen; it is threatening and requires high priority focus, limited response time, characterised by uncertainty, complexity, chaos, and ambiguity (Modise, 2020). Managing and leading through a crisis re-quires a different set of skills instead of normal day-to-day leadership practices (Modise, 2020). A crisis requires immediate action to a very volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) event that is extremely fluid as the situation and variables at play constantly change. When man-aging and leading in a crisis, it becomes very difficult to quantify responses or actions that were taken at that time, as the leader often leads based on instinct, experience, information and situa-tions presented at that particular time, as well as insights from the team. The decisions are taken very quickly and put into action at a swift pace.

In a crisis, a leader’s real strengths are tested, and their fundamental weaknesses are re-vealed. During this time, we can determine if the leader embraces the challenges and take the necessary action to address them while mobilising the team. Will the leader be in the forefront or hide at the back? Will the leader take responsibility and find out what went wrong and work to-wards fixing it, or would he play the blame game and evade responsibility? Are the organisations and its leaders prepared to handle a crisis, more specifically a chaotic prolonged crisis, and have the skills and knowledge to navigate the team through it to survive and, more importantly, recov-er from it and thrive in the future? It requires heightened decisive strategic direction to lead the team from the unknown to the known.

The covid-19 pandemic, first discovered in the latter part of 2019 in the Chinese city of Wuhan, has spread across the globe at an astronomical rate disrupting businesses, communities, healthcare, economies, and social practices. In response, governments globally, including South Africa, imposed stringent lockdown levels, including local and international travel restrictions.

The resulting lockdown restrictions and the pandemic itself had created many challenges and changes in operations for both public and private entities in South Africa. Many public enti-ties, Eskom included, were forced overnight to switch to remote working conditions for many of their staff. Staff at Eskom had to instantly become technology savvy and adopt various forms of technology as new modes of communication, engaging and performing their duties, as they sim-ultaneously had to take care of their family and household as well do home-schooling. A work-ing environment that they were very unfamiliar with. Further to this, Eskom had to speedily im-prove and upgrade its information technology to accommodate the changes in the working envi-ronment, resulting in unplanned expenditure and delays. Managers now had to engage with their staff using online meeting platforms such as Teams, Zoom, and Google Meets without having the requisite training and experience. Staff at Eskom is reliant on office computers, printers, scanners, faxing machines and Wi-Fi connections. For many staff that did not have company lap-tops, cellphone and data provisions, this did prove challenging, especially if the household had only one device. Decision-making at Eskom is very rigid, with often a top-down approach, with a minimal delegation of tasks and accountability being awarded to their subordinates. Collabora-tive decision-making and brainstorming was not the norm at Eskom. The situation was so fluid that decisions and strategies changed every day, at times, every hour.

This study examines the views of senior managers in terms of lessons learnt from the covid-19 pandemic to help inform their leadership approach as they begin to plan for the future. Following on this background, the study presents a review of the literature, followed by a discus-sion on the research methodology adopted in the study. Thereafter, a presentation of the results and a discussion is presented followed by the link to the literature. The study draws to a close by providing a summation of the results.

Literature Review

Crisis Leadership

In today’s climate, a crisis is inevitable. It is unknown when it happens and how it hap-pens; it is threatening and requires high priority focus, limited response time and is enveloped with uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (Modise, 2020). Managing and leading through a crisis requires a different set of skills as opposed to normal day to day leadership practices (Modise, 2020). A crisis requires immediate action to a very complex, ambiguous event that is extremely fluid as the situation and variables at play constantly change.

When managing and leading in a crisis, it becomes very difficult to quantify responses or actions that were taken at that time, as the leader often will lead based on instinct, experience, information and situations presented at that particular time, as well as insight from the team. These decisions are taken very quickly and put into action at a swift pace. Thus, crisis leadership can be defined as the manner in which the organisation uses strategies to deal with an event that places undue threat on the organisation’s financials, stakeholders and the ability to serve its cus-tomers. It also relates to the ability of the leaders and employees to deal with the crisis event ef-fectively. Modise (2020) asserts that crisis management deals more with the operational aspects, while crisis leadership involves oversight of the operational aspects and providing direction; however, greater focus is on providing “vision, direction and the big-picture thinking”. Thus, it is important to know what is happening on the ground level, but focus needs to be placed on plan-ning ahead and providing strategies to take the organisation through the challenge towards re-covery and post-recovery.

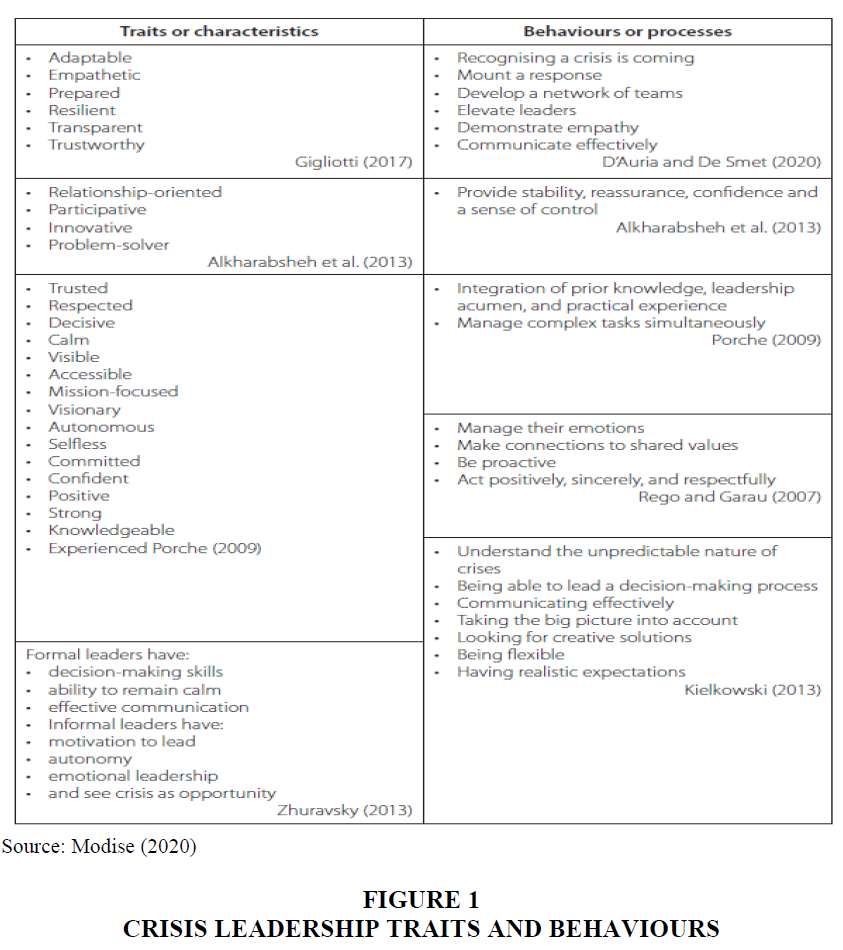

According to the Centre for Creative Leadership webinar “Government Leadership after Crisis: Reframe Your Mindset and Expand Your Tool Set”, the presenters illustrated the differ-ences between leading and managing a crisis. When leading in a crisis, the leader needs to focus on the human and mechanical side of the business. On the human side, they need to show com-passion and caring, display authenticity in their actions and empower the organisation at all lev-els while showing clarity and decisiveness in what will be done and how it will be conducted. While on the mechanical side, the leader needs to manage the systems, processes and structures, by making and taking decisive actions, being consistent and constant in their communication while being results and revenue-focused. A leader’s real strengths are tested, and their funda-mental weaknesses are revealed. Modise (2020) researched key traits and behaviours leadership should possess for managing a crisis and posits the following traits (Figure 1):

A crisis like Covid-19, which has been increasing in severity, spread and over a pro-longed period and still going strong with South Africa experiencing numerous waves of the virus outbreaks have disrupted senior managers at Eskom decision-making processes and how they lead and manage their teams. Traditional leadership approaches and decision-making were found to be redundant to navigate in this pandemic (Geerts, 2020). Scharmer (2007a&b) purported this sentiment in where it was postulated that in a crisis, due to the varying degrees of complexities and uncertainties causing immense chaos in society, organisations need leaders to “operate from the highest possible future, rather than being stuck in the patterns of our old experiences” to manage the chaos. However, leader’s current leadership behaviours depend on patterns of our past actions (Scharmer & Kaufer, 2013), which is not the best way to lead in an environment overcome with VUCA. Haedrich writes that although organisations are slowly returning to some kind of new normality, greater demands are being placed on the leaders' role post the Covid-19 crisis. The crisis has revealed much gapping weakness in leadership competencies. Competen-cies that were once successful before the crisis had proven ineffective in managing and leading through the crisis writes Haedrich. McNulty & Marcus assert that organisations often fail during a crisis as most often the situation is over-managed and lacks leadership. The reasons are three-fold: Leaders tend to take a narrow view of the situation. When faced with a threat, the brain au-tomatically defaults to taking a narrow focus and not taking a broad, holistic view. To break out of this narrow focus, leaders are required to step back and go within their mental framework.

? Leaders get caught up with day-to-day management instead of planning for the weeks and months ahead. They are reluctant to delegate and release control during this period and feel they have to do it all, micromanage or take control by creating additional layers of protocols and approval processes that delay response times instead of having faith and trust in the current system, processes and team. This actually disrupts the crisis management and recovery processes in place. They need to create clear guidelines and principles and then “let go” of the responsibility to others.

? Due to the chaos a crisis creates, leaders are focused on the business side of the organisation and for-gets about the human element – the people. People make the organisation and help realise their goals and objectives. Not everyone copes well during a crisis, and leaders need to show empathy, humility, understanding and support. They need to unite the team towards a shared vision and response. Be transparent, specific and clear to the team about what is happening and the plans in place. Assure them that all will be well. Be the glue that holds the team together..

Dileep (2020) postulates that the Covid-19 pandemic has allowed leaders to rethink their existing business, operational and leadership models. Kok & van den Heuvel (2019) asserts o remain competitive in a VUCA world, traditional leadership models and styles will not suffice as hyper-innovation, creativity and adaptability are required. It is vital for leaders to possess quali-ties of visionary, understanding, collaboration, clarity, flexibility, agility, and creativi-ty/innovation, and risk-taking. The situation demands leaders to be strong mentally, physically and emotionally. It requires leaders to continuously reflect on lessons learnt and how best to im-prove their decision making and behaviour as they move forward.

For leaders to be effective during the Covid-19 pandemic and post the pandemic, they needed to first prioritise their mental and emotional health together with that of their team mem-bers and subordinates. They can only lead if they are in the correct frame of mind. Tasks can only be completed if the leader/manager and their workers are of sound body and mind, postu-lates. During the pandemic D’Auria & De Smet (2020) acknowledge that at times on the spot/immediate action was required; however, they advise managers during a crisis to be in a cy-cle where they constantly “pause-assess-anticipate-act”.

LeMaster (2017) postulates that for leaders and organisations to succeed in the knowledge era characterised by VUCA, they need to be adaptive, innovative, change their men-tal models, be agents of change and embrace diversity. They also need to “embrace opposition and criticism with truly open minds, listen closely to our perceived adversaries, put self-interest aside, and work together to achieve “the greater good” for our organisations, our people, and our social systems” (LeMaster, 2017). A sense of collective accountability, responsibility, and leadership for the greater good seems to permeate post the crisis. The Covid-19 pandemic crisis has given leaders at Eskom an ideal opportunity to reflect on the pandemic and lessons learnt, thereby reassessing their leadership approach for the ‘new world’ that the virus has created.

Methodology

The research methodology adopted for this study was qualitative in nature. The exploratory research design was guided by the interpretivist approach (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; ?ukauskas et al., 2018; Van Slyke & Simons, 2020) and was selected for this study as it is aimed to explore lived experiences from senior managers regarding the covid-19 pandemic to help them lead post the pandemic. The target population consisted of senior managers at Eskom, a large utility SoE in South Africa. Using purposive sampling, an online open-ended questionnaire was sent by the Human Resources Department of Eskom, using MSForms to the selected participants. In total, 65 senior managers completed the open-ended questionnaire. An opened ended online questionnaire was chosen as the most suitable instrument in terms of Eskom's policy and regulation regarding research conducted by parties external to the organization. No language barriers existed as all respondents were well versed in the English language, and no special concessions were required. The qualitative data was analysed using the software Nivivo Pro12. Thematic and content analysis were performed on the data. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (HSSREC/00001143/2020) and a gatekeeper letter from Eskom. Each participant in the study had to accept informed consent before participating in the study.

Research Findings

Based on the analysis of the essential qualities and traits senior managers had learned from the pandemic to help them lead post the pandemic, the main theme that emerged was Business Success, with four sub-themes that emerged from the tree-maps analysis, and within these sub-themes, various themes had emerged, as shown in Table 1 below. The discussion below will unpack and discuss these themes. The discussion will be centered on sub-themes 1-4, taking into account elements that emerged within each sub-theme.

| Table 1 Key Themes and Subthemes – Lessons Learned from Covid-19 Pandemic | |

| KEY THEME and SUBTHEMES | Responses |

| BUSINESS SUCCESS | |

| 1. Greater Care of the Staff | 12 |

| Empathy | 7 |

| Leadership and HR Focus over Process and Management | 10 |

| Trust and Empowerment | 14 |

| 2. Improve Flexibility and Agility | 29 |

| Scan the Market, Plan, Strategies and Restrategise | 12 |

| Input and Decision-Making Power | 9 |

| Teamwork, Engagement and Collaboration | 25 |

| Up skill and Empower | 5 |

| 3. Self-care and Family Support | 4 |

| 4. Unlearning Old Ways and Being More Proactive and Innovative | 25 |

| Accountability | 5 |

| Communication | 9 |

| Transparency | 5 |

Greater Care of the Staff

One of the critical variables required for an organisation as well as a managers success is its people. A total of 12 citations indicated the importance of staff's mental and physical well-being. Within this theme, three additional sub-themes emerged from the analysis: Empathy; Leadership and HR Focus over Process and Management, and Trust and Empowerment. The importance of taking care of the organisation's human side when leading through a crisis. Managers need to have compassion, authenticity, caring and resolve. Connor states that leaders who were successful during the Covid-19 pandemic “prioritized compassion over professionalism”. These qualities of compassion, understanding, empathy and staff well-being emerged from the senior managers' responses to lessons learned from the pandemic.

Managers noted that they need to be more cognizant of their team, their emotions, and their challenges in the years ahead. Key terms used most often were “staff are your assets, put people first, safety, staff well-being, understanding and support of staff, trust, empathy, keeping in touch, listen, up-skilling, learning and change”.

During the pandemic, senior managers at Eskom put their team members needs before their as they had realised the value and contribution of their team members and will focus on this; as Respondent 9 stated,

“I put them first as I am only as good as my team are” and with Respondent 2 making a compelling statement “take care of your people if you want them to take care of your business. People first and operations will follow and be successful”. With Respondent 21 asserting that “Your staff is your assets”.

Further to this, the importance of keeping in touch was also noted,

“Touching base with the team to keep the sense of togetherness”. (Respondent 31).

Working through the pandemic, managers realised that not everyone adjusts well to change and the importance of actively listening to their team and being open to their ideas as Respondent 28 and Respondent 2 respectively cites:

“Listen twice as much as you speak. Staff wants to be heard. Do not take things for granted as change is constant and not everyone adjusts well” and “Listen more and be more open to my staff and their ideas”.

Further to this,

“Trust in your team is vital” (Respondent 10) as

“People can be trusted to work independently” (Respondent 18) and

“Work from home” (Respondent 43) as they have proven to be

“Actually more productive” (Respondent 50). Similar feelings were expressed by Respondent 35, “Trust in your team. Show empathy and listen more”.

Covid-19 has proven that managers do not need to be with their team physically to be effective in what they do.

Literature advises managers to take accountability for their actions and delegate tasks by handing out more accountability and responsibility to their team members (Palmer, 2020) while providing more of a leadership facilitator role than micro-managing. Respondent 29 advises on giving the

“Team shared goals and responsibilities and allowing them to do their job while you check-in if they require support” as being “most helpful”.

A VUCA environment is continuously changing, and the staff needs to be equipped with vital skills, as postulated by Moore (2015) and Palmer (2020). Having leaders and staff with the right skills, experiences, knowledge and training are critical for surviving in a volatile environment (Kok & van den Heuvel, 2019). Managers must learn and relearn and encourage continuous learning and create an enabling environment that allows learning to occur. These points were echoed by Respondent 2;

“Encourage up-skilling and development of my staff to equip them with skills necessary to weather unpredictable times”.

Leaders and their staff must be trained in the presenting perspective; otherwise, they will continue to repeat behaviours that are not fit for purpose and are dysfunctional. Behaviours must be relevant to the context, with strategies being created that are fit for purpose and not based on what worked best in the past. Respondent 6 stated

“Change is real, and our teams and leadership must be prepared to move out of comfort zones to learn new ways to thrive in such turbulent times”.

Respondent 44 summons up the sentiments quite eloquently and which is in alignment with literature.

Change is definite, and it is important to train our people to accept change and look for the opportunities in the challenges. Teamwork and constant engagement, and collaboration are vital. Transparency and accountability, and knowing you have trustworthy team players are vital. Change can be viewed both from a positive or negative light.

In a positive light, it opens doors to new opportunities and or improved ways of doing things. However, it can be very threatening, causing much insecurity and anxiety as many people do not adapt easily to change. The leader or the manager's role is to help ease the team's anxiety by providing a clear plan of action. Mistakes do happen, especially in complex, chaotic, challenging situations, and it must be known that it is ok as long as one can learn from it as quickly as possible and the error is rectified. Individuals who have evolved in their worldview of thinking and often self-reflect tend to view change positively. Respondent 47 alludes

“That change is not always bad and is a useful driver for fresh thinking, that flexible schedules and working from home enable people to perform at their best - one does not have to fear that outputs are compromised”.

Respondent 44 states it is important

“To embrace the new way of working and adapting it to suit everyone's needs”.

Managers found that frequent catch-up calls with the teams to check their mental well-being and do status check-ins to determine what assistance was required to complete their tasks was very helpful. These behaviours helped lessen anxiety among the team, and team members were found to be more collaborative and innovative in their thinking as they looked for new ways to complete tasks. The mentality of “we all are in this storm together, and we will weather it together” constantly came through from the data. Teamwork, support and collaboration were common sentiments for the managers as they reflected on the pandemic and what worked and did not work, with a focus on

“Results and service delivery and not micromanagement of staff” (Respondent 54).

To build trust and ensure all members are clear as to what is done, Respondent 15 states that “honesty when communicating with the team, the setting of clears goals and providing good direction to staff on achieving the goals” is vital.

Senior Managers at Eskom in their statements have corroborated with Saunder's et al. (2015) critical qualities of trust, accountability and team leadership cited in LDC on the creation of a results-oriented culture, the promotion of self-development, the creation and setting of clear guidelines, leading from the centre, provision of accurate timeous information and the adjusting of targets to the current situation as being some of the essential qualities for leading in a VUCA environment based on their experience of managing and leading through the Covid-19 pandemic.

Improve Flexibility and Agility

Four subthemes emerged within this theme: Scan the Market, Plan, strategize and Re-strategize; Input and Decision-Making Power; Teamwork, Engagement and Collaboration and Up-skill and Empower. Agility, adaptability, flexibility, proactiveness, responsiveness, alert, strategize and re-strategize, adapt to change, empowerment, up-skilling and scan the environment were the recurring terms used by the senior managers as vital lessons learned from the pandemic, with Respondent 28 eloquently stating that

“COVID has taught us that being complacent is a recipe for disaster. Leaders must be vigilant, alert and responsive to adapt quickly to changes and different situations on short notice”.

“The world is unpredictable; thus, as leaders, we need to be adaptable for different situations at short notice”, wrote Respondent 51.

It is crucial in a crisis to allow for flexibility to increase response time. During Covid-19, the situation was extremely fluid, and people had to be able to change and or adapt in a short space of time; as Respondent 3 stated,

“There is no certainty in business, and we have to be adaptable and respond quickly to change”.

Thus, decision making in a volatile environment requires proactiveness, decisiveness, creativity and innovation, with leadership being flexible, adaptable and agile in their leadership approaches. This can be achieved by having up-to-date, relevant information, by regularly and

“Constantly reviewing the market and our strategies are a must if we wish to survive and thrive”, cites Respondent 3 and soliciting input from the team and engaging in discussions to make informed decisions.

Respondents 2, 5, 7 and 15 cited the importance of

“Listening more and being open to new suggestions, ideas and innovations, and the notion of collective brainstorming and strategy creation” emerged from the data.

Respondent 5 expressed this sentiment, be

“Open to all views and shift through unnecessary clutter to allow clear thinking”.

While Respondent 13 asserted that his/her

“Team is strong, and if they are provided with a context and given the opportunity to take responsibility, they will put forth ideas”.

Respondent 39, indicated that it is important to

“Create a more conducive environment for brainstorming and innovation”.

Covid-19 has proven the flexibility of many positions as it does not require the physical presence of an individual, with remote working being effective.

“People can work virtually as long as their outputs/deliverables are clear”, stated Respondent 54.

For this to be possible senior managers indicated that “trust” in the team and the manager must prevail. Apart from being “agile”, it is also essential to be “non-fearing” and “resilient” so your team knows they have a strong leader whom they can turn to and rely upon were also expressed by the managers.

Some managers indicated the need to employ more “lean thinking skills” as it “proved to be a key success” (Respondent 59).

With Respondent 12 stating that in the future, it is important to

“Constantly be adapting and modifying the direction and the path to attain the goal”.

“Strategize and re-strategize based on the environmental stimuli” was echoed by Respondent 8 and many other managers, with Respondent 17 highlighting that “business models must not be cast in stone.”

“The disruption of leadership behaviours that build on the familiar. We need to break down old ways of thinking and doing things,” highlighted Respondent 30.

Corroborating these study findings are the findings of BDO (2020) and Baruch et al. (2021), which found that leaders who had focused on the essential tasks; strategized and re strategized, performed operation excellence, used lean tools and evaluated and reflected on the strategies implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic, were able to successfully weather the storm of the pandemic with minimal impact on their business. In a crisis, it is not easy to focus on all aspects or tasks to be completed.

“Greater teamwork, clearer communication of shared goals, vision and plans” among the team members was seen as essential in a VUCA environment. Managers across the board reiterated the importance of “constant engagement and collaboration with the team and other departments”. These engagements and boundary spanning collaborations had given rise to

“Great ideas and results” (Respondent 21) and “Teamwork=success”, noting Respondent 37.

“Engagement, reflection and collaboration” are critical components of effective strategizing; however, to do this, team members and managers must embrace change; as Respondent 37 stated,

“We have to continually adapt to the environmental changes, and our staff must be open to change. Creating an environment that enables change and ideas are vital”.

“Adapting to change is key to maintain and fostering good relations,” wrote Respondent 38.

Covid-19 has proven to many that “we are much more adaptable than what we realise. Change under pressure takes place very quickly and works” (Respondent 42).

Thus, it is important for leaders and managers “to be able to rapidly embrace change at any given time as to proactively manage challenging situations that are unforeseen such as Covid-19” (Respondent 56).

“Consolidation, Co-operation and Collaboration are vital going forward”, cited Respondent 26.

To successfully embrace change, managers, leaders, and staff must have the required and sufficient skills for a crisis. One may be required to multitask, work across functions remotely, adopt new technology, think out of the box and provide creative, innovative strategies and solutions. To do this, Respondent 56 states I will

“Encourage up-skilling and development of my staff to equip them with skills necessary to weather unpredictable times” and the “new world” (Respondent 19).

Training and development has taken into account the changes in Covid-19 will help broaden one's practical skills and conceptual knowledge, with Respondent 63 stating,

“We work in very unpredictable times. To survive, we must be able to adapt quickly; thus, it is important to be knowledgeable, skilled and alert”.

Senior managers at Eskom stated that to “survive and thrive”, it is essential to be “alert” by “constantly adapting and modifying the direction and the path to attain the goal. Strategize and re-strategize based on the environmental stimuli” (Respondent 12) by “constantly reviewing the market and our strategies” (Respondent 3) to “make informed decisions under difficult situations” (Respondent 63).

While Respondent 62 believed “strategic thinking, innovation, agility and adaptability is critical for surviving turbulent times.”

Managers noted that people are “strong, resilient and committed” with the “ability to adapt to extreme situations, to still collaborate and make plans to resolve issues and provide solutions” (Respondent 31).

Covid-19 has proven to the managers at Eskom how strong and committed their teams are.

Unlearning Old Ways and Being More Proactive and Innovative

Being habitual and routine in a VUCA environment exposes one to significant risk. With globalisation and the rapid advancement of technology, the dynamic nature of the markets, the way we do business, customer needs, and the political and natural environment are continually changing, making business models redundant in a very short period of time. Adding a black swan event like Covid-19 to an already tumultuous environment has proven to be catastrophic for businesses, society and governments globally.

“Covid-19 has taught us that being complacent is a recipe for disaster”, cites Respondent 28.

Covid-19 has led to “the disruption of leadership behaviours that build on the familiar. We need to break down old ways of thinking and doing things” (Respondent 30). “Covid-19 has proven that mindsets operating on archaic models will not suffice” (Respondent 65).

Leaders, managers and employees that were able to reflect, assess the situation, abandon their old mental models of thinking and doing, come together as a team, brainstorm and collaborate to finding new ways relevant for the current situation were found to be successful in navigating the organisation through the difficult period. “Change being constant” was a recurring sentiment among managers; thus, as Respondent 7 cites, it is essential to

“think holistically and to the future also planning for the unexpected,” as “change is real and our teams and leadership must be prepared to move out of comfort zones to learn new ways to thrive in such turbulent times” (Respondent 6).

To do this, it is essential to “continuously learn and unlearn and relearn the ways we do things” (Respondent 7) and be “be more proactive, strategic and innovative in my thinking” (Respondent 41) and “embrace the new way of working and adapting it to suit everyone's needs” (Respondent 43).

Respondent 29 goes on to say that “leaders must be vigilant, alert and responsive to adapt quickly to changes and different situations in a short notice” while also learning to be “be more flexible in my thinking and actions. Being agile, responsive and adaptable is the ingredients of the new normal” (Respondent 2).

Respondent 8 advises to “engage, reflect, and collaborate. strategize and re-strategize all time. Do not be complacent. Look for new innovative ways to ensure excellence,” with Respondent 25 highlighting the “need to be more aware of the environmental changes and plan more proactively.”

Moore (2015) propagates the vital-ness of visionary and out of the box thinking to succeed in a VUCA environment. Respondent 52 corroborates “the importance of getting people to think beyond the horizon and to adapt to change”.

At the same time, Respondent 65 spoke about removing “complacency in thinking and actions”, citing “innovation, creativity and proactive strategic critical thinking” as essential.

In addition to these qualities, managers also cited the qualities of “accountability, adaptability, transparency, and trustworthiness”. For some managers, as cited by Respondent 22, Covid-19 had “brought out the best” in their Teams while it revealed their “areas of weaknesses”. Moreover, it helped him/her identify areas of self-improvement: “I need to change from my old way of managing and thinking to a new collaborative, inclusive manner. I need to be more alert, flexible and communicate better”.

Failure of interventions often arises due to poor communication. Managers can create the perfect plans on paper; however, if they do not communicate them clearly and in a manner that is easily understood by the team, confusion, anxiety and conflict sets in, causing the perfect plan to become ineffective, costly and time-consuming. Respondent 18 alludes to the importance of communication by stating, “Communication is key. You must be able to articulate what is required and then step back to allow others to follow through”.

Furthermore, “frequency of communication, honesty when communicating, and the use of different communication mediums” recurrently emerged from the data. Failure to communicate honestly, clearly, timeously and in the language and terms that are easily understood by the team in the appropriate format and sizeable amounts can easily overwhelm the team members, especially when faced with a crisis.

Self-Care and Family Support

One of the key points that emerged from the data and literature was the importance of “self-care, mental and emotional well-being, and safety”. Managers at Eskom prioritized the mental and emotional health of their Team as well as their own. Further to this, focus on the safety of the team members was critical as well.

Respondent 41 states the importance of “family support during tough times and focus more on personal safety, self-management and personal discipline are key and very important”.

Similar sentiments were expressed by Respondent 56 and Respondent 20, further highlighting safety and well-being and the importance of staff to the organization “Focus of safety and well-being of staff. Your staff is your assets”. Change is inevitable, and how managers and leaders respond to the changes will determine if the organisation succeeds or fails. As Respondent 49 states,

“Our History can be an impediment to our progress if we ONLY depend on it as radar for our future,” with Respondent 48 highlighting that “Change is constant and the importance to constantly learn, unlearn and relearn as we adapt to new situations”. Thus, “teamwork, collaboration and creative, strategic thinking sessions are important. Remove complacency in thinking and actions. Covid-19 has proven that mind-sets operating on archaic models will not suffice. Innovation, creativity and proactive strategic critical thinking are essential” (Respondent 65).

Summation of the Findings

The thematic analysis has established that the lessons managers have learned from the pandemic to help them lead post the pandemic are that they need to:

1. Be more empathetic, supportive, caring and understanding towards their staff and create a safe working environment for them. They also need to show honesty, humility and trust towards their team.

2. Build and strengthen on their leadership qualities of accountability, responsibility, agility, proactive-ness, decisiveness, flexibility, responsiveness and speed to action.

3. Communicate more and ensure that communication is clear and specific, and timeous.

4. Embrace collaboration, engagement and be open to ideas within and across teams and stakeholders.

5. Develop their innovation and creativity skills and encourage creativity within the team.

6. Be accommodating, adaptive, inclusive in their leadership approach and decision-making.

7. Listen more attentively to their team members and be open to change and new ways.

8. Promote more teamwork, brainstorming and scenario planning among the team. The empowerment of the team is very important.

9. Be clear and transparent when setting goals and communicating their vision as they direct the team thereof.

10. Lead more and focus on being results-oriented and the teams' well-being and development. This ulti-mately leads to service delivery, customer satisfaction and sustainability.

11. Self-management; Self-care and Self-reflection.

12. Adopt a more strategic analytical holistic thinking mind-set.

13. Understand that change is constant, and learning must never stop as well as the adoption of new sys-tems and technology. It is important to learn, unlearn and relearn new ways of thinking and doing. Cross-skilling and up-skilling is vital.

14. A change in mental models is required to survive and thrive in the VUCA environment. Be a solution seeker.

15. Plans are not cast in stone; thus, they need to learn to strategize and re-strategize at all times.

16. Conduct more environmental scanning and embrace the qualities of sensing, probing and awareness decision-making.

These essential qualities and traits that had emerged from the qualitative data corroborate with literature findings for leading in a complex, volatile, crisis environment (such as: Moore, 2015; Van Velsor et al., 2016; Daigle, 2017; Donkor & Zhou, 2019; Towler, 2019; D'Auria & De Smet, 2020; Dileep, 2020; Geerts, 2020; Proches, 2020; Rahi, 2017; Modise, 2020) and based on the key qualities displayed by leaders who had successfully managed to lead their teams dur-ing the pandemic, (Deloitte, 2020; Palmer, 2020; Pitstick, 2020; The Rebuilders, 2020; USB-ED, 2020)

1. Empathy, compassion, composure & support

2. Self-reflection & mindful work

3. Communication, collaboration, open to new ideas & learning

4. Health & positivity

5. Flexibility, adaptability, agility & decisiveness

6. Transparency, authenticity, trustworthiness & accountability

7. Strategic, visionary & anticipatory

8. Being mentally, emotionally and physically present

9. Re-prioritising of targets/projects & setting achievable goals

Based on the results, senior managers behaviour change had aligned with the leadership traits and qualities required for leading in a VUCA environment, and the theoretical framework of Theory U. Managers found them being more empathetic, understanding, supportive, collabo-rative and engaging. They reflected more and found themselves doing more deep thinking and understanding their weaknesses. Amidst the chaos, challenges, and anxiety, they realised their team's importance and that they could trust and depend on them, with many team members showing greater productivity due to remote working. The situation forced them to relinquish var-ying degrees of control and increase delegation, accountability, which allowed the emergence of ideas and innovative solutions from their team members. Managers had to abandon their old ways and adopt new ways relevant to the situation and realised the significance of continuous learning, unlearning, and relearning to survive and thrive.

Senior managers acknowledged that change is inevitable. It is essential for them and their team to embrace change and create a culture of evaluation and re-strategizing to manage situa-tions better as disruptions occur. To ensure better preparedness for the unknown, scenario plan-ning and reflexivity is required. Building resilience within the team and themselves and learning to be more accommodating to others’ viewpoints by creating an enabling environment and set-ting time aside for employees to do more brainstorming as they explore their creative/innovative abilities is required. Further to this, they felt it is essential to sharpen their strategic, analytical, holistic thinking and planning skills while leading more, listening more and being results-oriented.

Conclusion

The study concludes that the senior managers were equipped with the right qualities and traits to lead their team during the crisis and have extracted lessons from this experience to turn adversity such as the Covid-19 pandemic into an advantage where Eskom begins to thrive. To succeed post the pandemic and ensure better preparedness for future black swan events and cri-ses, senior managers need to have high levels of emotional intelligence, better self-management and self-care skills, and the ability to learn to abandon old rigid ways of doing and thinking by embracing the principles of Theory U and being more adaptable, agile, flexible, responsive and collaborative. Frequent communications that are clear and specific play a vital role in the team's effectiveness and efficiency. To build trust in a team, they need to show accountability, trust-worthiness, honesty, clarity, and transparency in setting goals and vision. Areas they need to work on were innovation, creativity, problem-solving skills, greater relinquishing of control, and empowering their team. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the team had proven they could work unsupervised, and they are productive, able to multitask and are insightful novel strategy devel-opers if given the opportunity. Policymakers and leaders fail to consider and factor in elements of uncertainty and contingency plans when making decisions. Post-crisis analysis reveals salient factors that were found to be the triggers in the crisis were omitted in the planning and effective-ness phase. Thus, highlighting the importance of scenario planning, contingency activities and collective thinking during strategic decision making

Leadership in the 'new world' created by the pandemic requires senior managers to ask uncomfortable questions, disrupt their thinking, attack their current mental models and reconfig-ure them by learning to address the ambiguous challenges with somewhat indeterminate solu-tions. Senior managers need to be challenged to reassess and reconfigure how they lead and do business to serve all stakeholders' needs. They are required now to be more of an influencer, change agents, motivators, mentor, guide and coach.

References

Creswell, J.W., & Creswell, J.D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

D’Auria, G., & De Smet, A. (2020). Leadership in a crisis: Responding to the coronavirus outbreak and future challenges. Psychology, 22(2), 273-287.

Daigle, J.L., & Matthews, B.L. (2017). An evaluation and application of complex adaptive leadership: A fuzzy logic and neural network approach. The Journal of International Management Studies, 12(2).

Deloitte. (2020). The heart of resilient leadership: Responding to Covid-19 A guide for senior executives.

Dileep, K.M. (2020). Reflective Leadership in Crisis. Horizon Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, 2(1), 11-18.

Donkor, F., & Zhou, D. (2019). Complexity Leadership Theory: A Perspective for State-Owned Enterprises in Ghana. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 7(2), 139-170.

Geerts, J. (2020). Leadership lessons and hope for a post-crisis world. BMJ Leader.

Kok, J., & Van Den Heuvel, S. C. (2019). Leading in a VUCA world: Integrating leadership, discernment and spirituality (p. 209). Springer Nature.

LeMaster, C. F. (2017). Leading change in complex systems: A paradigm shift.

Modise, K. (2020). SA’S Electricity Problems 25 Years in the Making – Expert. What will it take for Eskom to be able to supply the entire South Africa with power? EyeWitness News.

Moore, D. L. (2015). Leadership in the 21st century environment; A proposed framework. Department of the Navy Leadership Essays.

Palmer, W.J. (2020). 10 Traits of Highly Effective COVID-19 Leaders. Diagonstic Imaging.

Pitstick, H. (2020). 4 key leadership skills for a post-COVID-19 workplace. FM Magazine.

Pramjeeth, S. (2021). Leadership of state-owned-enterprises in a volatile environment: A case study of Eskom.

Proches, C.G. (2020). Order in disorder (opinion piece of how the global pandemic, Covid-19 had impacted the job of the leader and the workforce).

Rahi, S. (2017). Research design and methods: A systematic review of research paradigms, sampling issues and instruments development. International Journal of Economics & Management Sciences, 6(2), 1-5.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Saunders, M. N., Lewis, P., Thornhill, A., & Bristow, A. (2015). Understanding research philosophy and approaches to theory development. In Research Methods for Business Students (8th Edn.). Pearson Education Limited, Harlow.

Scharmer, C. O. (2007). Addressing the blind spot of our time: an executive summary of the new book by Otto Scharmer "Theory U: leading from the future as it emerges". Social Technology of Presencing.

Scharmer, C. O. (2007a). Theory U: Leading the Future at it Emerges. Cambridge, MA: The Society for Organizational Learning. Inc.(SoL).

Scharmer, C.O., & Kaufer, K. (2013). Leading from the emerging future: From ego-system to eco-system economies. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

The Rebuilders. (2020). This is the most essential skill leaders need to work through the COVID-19 crisis. Fast Company.

Towler, A. (2019). Complexity leadership: Understanding organizations as dynamic and complex systems of social interactions.

USB-ED (2020). 6 leadership qualities that matter during a pandemic. University of Stellenbosch Business School.

Van Slyke, S., & Simons, A. (2020). Leadership in the COVID-19 crisis: The importance of building personal resilience. Control Risks.

Van Velsor, E., Turregano, C., Adams, B., & Fleenor, J. (2016). Creating tomorrow’s government leaders an overview of top leadership challenges and how they can be addressed. Center for Creative Leadership.

?ukauskas, P., Vveinhardt, J., & Andriukaitien?, R. (2018). Philosophy and paradigm of scientific research. Management Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility, 121.

Received: 12-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. ASMJ-21-9775; Editor assigned: 15-Nov-2021, PreQC No. ASMJ-21-9775(PQ); Reviewed: 6-Dec-2021, QC No. ASMJ-21-9775; Revised: 23-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. ASMJ-21-9775(R); Published: 02-Jan-2022