Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Issues of Subsidy on International Trade: A Case Study Between the United States and Canada

Le Van Dung, Thu Dau Mot University

Keywords

Trade Disputes, The United States, Canada, Subsidy, FTA

Abstract

The U.S. and Canada have been trading partners for as long as they both exist. Despite such intimacy, disputes persisted throughout their history. Most notable of all those cases in their dispute over subsidies and countervailing measures concerning softwood lumber products. This case revolves around the claim of The U.S. that Canada subsidized their lumber trade and Canada’s opposition against the countervailing duty imposed. This dispute lasted over 25 years and took form of four different phases. Yet, this case has recently risen again, but for matters of continuity, this paper will only look into the events before.

Introduction

Due to demands exceeded the supply of U.S. mills, Canadian softwood lumber entered the U.S. market. With great production capabilities and long-term business settings, Canadian exporters nourished a prosperous affair of lumber trade. Thus, many jobs were created and consumers were able to enjoy a variety of high quality products. However, beneficial they may be, the U.S. have sought to impose duties on Canadian lumber, time from time again. Canada, regardless, challenged the U.S. before the WTO and came out victorious, as well as scathed and injured (Foster, 2008).

Lumber I: in 1982, some provinces of Canada were under investigation by the U.S.’s Department of Commerce (DOC). Next year, they concluded that the stumpage was not for any specific industry, which is inconsistent with the definition of Article 24 under WTO’s agreement. Hence, the imposing of duties did not take place.

Lumber II started in 1986, the DOC, now was cracking down on similar cases and lobbied to push the claim once more. This time the specificity test checked out. Consequently, a 15% duty was imposed. NAFTA favored the U.S. trade law and WTO failed to reach a final decision. In the end, both parties signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) as Canada imposed a 15% charge on their lumber exports.

Lumber III happened 1991 as Canada terminated the MOU, forcing the U.S. to once again performed investigations. As a result, a new rate of tariff was introduced, at 6.51%. Canada successfully appealed the findings to the panels under the FTA. However, the U.S. challenged the decision, but failed as the duty was revoked later in 1994.

In 1996, on terms that the U.S. reimburses Canada with the duties charged during Lumber III, the parties entered consultation of the 1996 softwood lumber agreement. This time around, the U.S. had amended its trade laws and expected for Canada’s defeat. Despite many efforts, in 2001, the arbitral panel ruled that the U.S. had compromised the agreement as their Customs authority changed classification designated identification numbers of the products.

After the 1996 Softwood Lumber Agreement had been out of date, the U.S. Coalition for Fair Lumber Imports filed petitions regarding countervailing and anti-dumping duties against Canadian softwood lumber. In august 2001, the DOC determined that Canadian softwood lumber had been subsidized, in comparison with Washington’s stumpage. They also found a “critical circumstance”, when exports surged after the expiration of the SLA. Thus, bonds were posted so as to cover the duties. The final determination of countervailing and anti-dumping linkage case was revealed in March 2002. Consequently, British Colombia, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec exporters suffered both duties. Other exporters were free due to claim of private properties constituting production. July 2003 witnessed the capping of Canada’s softwood lumber exports. Later, NAFTA deemed the duties were higher than necessary and the WTO decided that U.S.’s claim of subsidizing was irrelevant. In 2005, the NAFTA ruled out U.S.’s claim of Canada’s violation. In March 2006, the WTO, in Canada’s favor, finalized that there had been no subsidy. Also in 2006, Canada and the U.S. informed the DSB that they had reached an agreement.

Later on, another conflict erupted, again, the U.S. claims that that they rightfully deserve Anti-dumping and Countervailing duties from Canada. This transgression has yet to fully elope, but both parties are determined to win the other over.

As on previous studies concerning the matter, there have been many articles, books by researchers and by the governments. However, accesses to books are limited, leaving entry to available articles and studies already used as materials for this compilation.

Aims

Through investigating the mentioned case, this study is expected to illustrate the history of the case, its core problem, how the Canadians won, and what we can learn from this experience.

Methods

This study was the product of a series of secondary researches of materials available online and consultation of readily available documents related to the subject.

Results

The U.S. has two specific standards to determine the levying of countervailing duties, which are the existence of subsidy and the injury in relation (Global Affairs Canada, 2017). Thus, through conducting the investigation, the U.S. was able to calculate the injury. However, the claim made on grounds that Canada was subsidizing its lumber industry is still controversial. Canada, in some states specifically, was setting low stumpage fees to its supporter (WTO – DS257, 2019). Subsequently, this type of performance could be considered as an actionable subsidy, as stumpage fee is supposedly collected by the government. In the times contemporary of this case, the government was providing the close to nothing of such fee. The Panel’s findings, again, supported the U.S.’s claim on grounds that governmental influence was substantial within the industry (WTO – DS257, 2019). Regardless, it was proven to be greatly amiss. To support those claims, the Canadian government had proven that the providence program was available in general and cover all industries, which is not complying to the specificity of Article 2 of the Agreement of Subsidy and Countervailing Measures. To illustrate, in Lumber I, Canada had multiple programs that encouraged businesses through tax incentives (Global Affairs Canada, 2013), which were made public, and did not give prices at a more favorable level. For example, to name some of these programs, there are Deductible Inventory Allowance, Capital Cost Allowance, Export Development Corporation, Similarly, the Key Panel also decided that the research conducted by the U.S. was not wholly extensive as the duty targeted finished products and failed to realize the benefit that moved from one producer to another. Despite the U.S.’s claim, Canada was not explicitly tied to provisioning the products with preferential prices. To add more, Canada, as well as the Panel and Appellate Body pointed out that the DOC was consistently changing their method to calculate the injury as it deemed such method was correct. Such conduct was condoned, yet, it failed to account for the fact that Canadian exporters were superior to their rivals in the U.S. In the end, the NAFTA insisted that the U.S. overtaxed its partner. In addition, the WTO denied the claim that Canada was subsidizing its produce. Ultimately, Canada was reimbursed with compensation by the U.S., and a new agreement came into action.

Discussion

Although the subject of trade was not a product of critical importance, it did turn out to be significant lesson for future endeavors. First of all, the U.S. is a formidable trade partner, who is willing to change internal laws and has great influence over other nations. Secondly, many agreements, despite their members, are still largely based upon the WTO agreements. However, the panels and the DSB, regardless of finding inconsistencies in the U.S.’s handling its obligations, was unable to enforce anything upon the entities. Canada fought until the end, and coerced the change of thought, allowing further negotiations. Ultimately, the nations agreed on another agreement, same as they did.

Recommendations

From the case between the U.S. and Canada, we suspect a great deal to be learned from the endeavour. It would be advisable for nations to peruse their agreements and consult thoroughly that of the WTO. Definitions should be carefully adopted and clarified for in this case, some findings were reversed due to lack of clarity, and the missing of common understanding. Debatable claims should be countered and challenged. Specificity is detrimental to establishing subsidy. Thus, it is dire for a claim to be valid. Injury accounting can produce inaccurate outcomes. Hence, once investigation starts, claims are likely to be valid. On the other hand, there are many things we can learn from Canada’s response. First of all, they handled the problem in a civil and complying way, abiding to agreements. Secondly, Canada was very cooperative during the investigation and the carrying out duties imposement. Thirdly, success was possible due to the ability to reason in accord and exploit the agreements. In this case, Canada had had wide-range programs that covered multiple fields and that made it impossible for the U.S to countervail. Also, Canada’s incentive was much too small to have substantial effect enough so that the Panels involved would consider the U.S.’s duties to be fair.

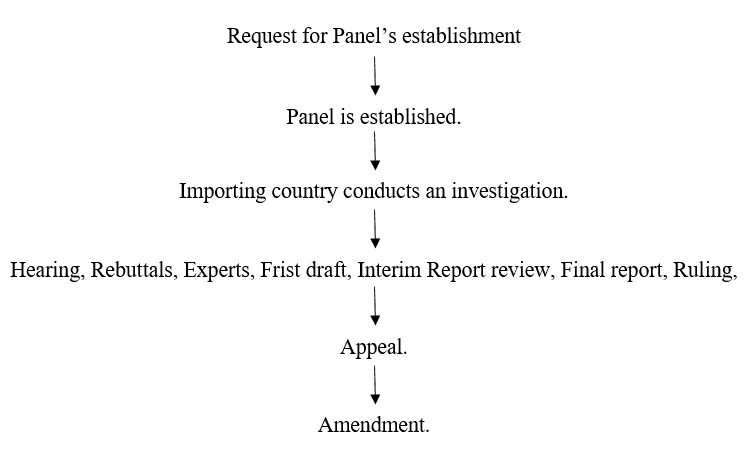

As for how the WTO would settle the case, the hurt country is lead through the following process, in light that the subsidy is an actionable one. Firstly, the two countries go through consultations. Next, if not settled, the dispute is brought before a panel, and goes under a long and Arduous process. Lastly, the panels gives a ruling or a recommendation, and allow some time for the parties to appeal before amendments are carried out. The process would be similar to the sketch below.

Not only did the parties present their dispute under the WTO, they also tried it under NAFTA first. NAFTA’s method is similar to this description. At the start, an industry can request a binational panel to be established, comprising of authorities. In Canada, it is the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), which makes dumping and subsidy determinations, while the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (CITT) conducts injury inquiries as whether or not the dumping or subsidy has caused injury or retardation (material retardation of the establishment of a domestic industry) or is threatening to cause injury to the domestic industry. In the United States of America, it is the Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, which makes dumping and subsidy determinations, while the United States International Trade Commission conducts injury inquiries.

Conclusion

Overall Conclusion

This research has provided us with a deeper understanding of how to determine a subsidy and knowledge about its definition, classification, and effectiveness under the WTO Agreement. The research also pointed out the outline of the investigation process on imported goods, said to be subsidized. It clarified one of three requirements to impose countervailing duties and how how to calculate the rate of subsidy by WTO’s standards. In addition, the research made known the authorities that are directly involved in the process of investigating subsidy and levying countervailing measures in the U.S. and Canada. A notorious case has been studied as well, regarding the dispute over subsidy between the great powers, the U.S. and Canada.

Limitations

Nevertheless, this research has its own limitations. Specifically, it was not done on grounds of full coverage of all articles and terms of the agreement. In retrospect, it can be derived that in order for actual appliance, more intensive research is required.

Recommendations

In the state of globalization and fierce competition, many countries, especially developing ones, subsidize their exports in one way or another since they consider subsidies as an important factor to their socio-economic growth. Subject to Article 27(a) of Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, many members acknowledge this persistence. Therefore, it is advisable that countries adopting this method should provide general, rather than specific, incentives to their industries, so as to avoid the terms of Specificity.

In reality, member countries need countervailing measures to fight off unfair trade practices, specifically subsidy, that may cause damage to their industry. As many developing countries still adopt this practice, confrontation is inevitable. Despite that fact, in some cases, the advantage is the result of location endowments of a country, allowing comparatively cheaper inputs. Hence, businesses, not to mention industries, should not only seek legal but also managerial solutions to their incompetency.

End Notes

Article 2 of Agreement of Subsidies and Countervailing Measures

U.S. Trade Remedy Law: The Canadian Experience, 1.5 Programs Determined Not to Confer Subsidies,

1.5.1 Federal and Provincial Stumpage Programs, paras. 1-2

U.S. Trade Remedy Law: The Canadian Experience, 1.5 Programs Determined Not to Confer Subsidies,

1.5.2 Federal Programs

US – SOFTWOOD LUMBER IV (ARTICLE 21.5 – CANADA), ASCM Arts. 10 and 32.1/GATT Art. VI:3 (pass-through)

US – SOFTWOOD LUMBER IV, GATT Art. VI:3/ASCM Arts. 10 and 32.1 (pass-through of benefit)

Refer to the findings of US – SOFTWOOD LUMBER IV by WTO

North American Free Trade Agreement, Chapter Nineteen: Review and Dispute Settlement in Antidumping/Countervailing Duty Matters, PART SEVEN: ADMINISTRATIVE AND INSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, Article 1904: Review of Final Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Determinations

Article 2. Specificity in ASCM

References

- Agreement of Subsidies and Countervailing Measures of WTO

- Abby, C.F. (2008). Summary and Explanation of the U.S.-Canada Lumber Dispute, accessed 7.

- Global Affairs Canada (2013). U.S. Trade Remedy Law: The Canadian Experience

- Global Affairs Canada (2017). Background - Canada-United States Softwood Lumber Trade.

- WTO – DS257 (2019). US – SOFTWOOD LUMBER IV.