Research Article: 2020 Vol: 19 Issue: 4

Investigating the Influence of SCs and PCs on Existence of Human Capital of Rural Entrepreneurial Activities and Small Businesses: Managerial Implications

Albert Tchey Agbenyegah, Durban University of Technology (DUT)

Abstract

Human capital represents one of the primary essentials to successful entrepreneurial activities. As such, there is the need to determine the relationships between specific and personal challenges and the existence of human capital towards rural entrepreneurial activities. This study seeks to empirically investigate the influence of specific and personal challenges on the existence of human capital of entrepreneurial activities. A quantitative approach was adopted aided by a 7 Likert-scale questionnaire to solicit primary data for theory testing in order to either accept or reject the formulated hypotheses. A total of 300 owner-managers were selected through the simple random sampling approach. The main reasons for using this approach are to avoid bias during the sample selection process and for more representation of research participants.

The author employed different analytical tools namely descriptive statistics, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient to test the relationship between specific (SCs) and personal challenges (PCs) on existence of human capital (EHC).

Empirically this study found that SCs in terms of marketing challenges experienced a weak negative correlation on EHC, in terms of environmental challenges SCs there is negligible positive correlation with EHC. Besides, the study found that SCs in terms of managerial challenges lack correlation with EHC. Also the study found that PCs regarding human resources challenges shows weak negative correlation with EHC. However, PCs in terms of record keeping shows negligible positive correlation with EHC. The study recommends that more training should be offer to owner-managers through the establishment of local entrepreneurial hubs. There is the need to provide tailored-made role models to help` rural owner-managers of small businesses.

Keywords

Owner-Managers, Entrepreneurial Activities, Human Capital, Specific and Personal Challenges.

Introduction and Research Objective

As research in entrepreneurship grows so is the unceasing interest and endless global recognition for entrepreneurship (Lin et al., 2012). Small businesses are highly valued as profitable sources of financial establishments (Agyapong et al., 2011). Accordingly, they constitute critical tools in developed and developing countries (Kongolo, 2010); its positive impact on job creation and other socio-economic activities cannot be ignored (Bosma & Levie, 2010). Yet, owner-managers of small businesses frequently points to varying challenges when asked to identify some inhibitors of business operations. At present, the existing small business environment especially in developing countries are overwhelmed by numerous challenges and growth inconsistency (Ahmad & Xavier, 2012; Nabi & Linan, 2011). These challenge broadly operations of small businesses. As a result, entrepreneurial activities in South Africa are largely confronted with high failure rates (Olawale & Garwe, 2010; Willemse, 2010). Several extant literatures support strings of small businesses in South Africa over the years (Chimucheka & Rungani, 2011; Tlhomola, 2010; Weeks & Benade, 2008). Given these challenges, the primary objective of this study is to empirically investigate the influence of SCs and PCs on the EHC.

Throughout this study, “owner-managers” means an individual who owns and manages small businesses as a family unit. Business decision-making is the sole responsibilities of owner-managers referred in this study as self-employed individuals who pursue entrepreneurial activities within industry sectors of transportation, retail and wholesale, fruits and vegetables, beauty salons, accommodation, cell phones repair services and providers of internet services to rural communities. The study defines “small businesses” as independent establishments owned and managed by individuals with employment volume of over 5 and less than 50 persons. This study further operationalised “small businesses” as business entities in rural settings that offers potential business opportunities. On the other hand, “entrepreneurial activities” throughout this study are the means through which individuals operate small businesses across industry sectors with the view to minimise rising unemployment. For clarity and to ensure that the stated objectives are realised, small businesses and entrepreneurial activities are used interchangeably throughout this empirical study.

The significance of rural entrepreneurial activities cannot be left unnoticed since it fills the unemployment gaps that continue to exist in rural settings. It is therefore important to understand the barriers that impede existence of human capital. Over the years, owner-managers have been threatened by challenges of not being able to engage skilled manpower and retain them. Other challenges include lack of entrepreneurial education and the general lack of skills training.

The current research outcomes will contribute positively to scientific body of rural entrepreneurship research. Besides, this research has the potential to guide owner-managers of small businesses and to steer rural entrepreneurial activities to become successful.

This study is structured as follows: initially, the study present literature overview of small business environment, the challenges and theory on human capital and entrepreneurship. Next a framework that underlined the study with supporting hypotheses was presented. Thereafter, a detailed account of the research methodology is outlined. In conclusion, the empirical findings are detailed after the section on data analyses. Discussions of the final results, conclusion, recommendations, management implications, limitations and future study are provided to conclude the empirical study.

Overview of Literature Studies

Given the high failure rates of entrepreneurial activities in South Africa, this study is designed to investigate the influences of challenges as stated in the conceptual framework. These challenges are briefly outlined and discussed in the next section. The following section discusses the small business and the nature of entrepreneurial environment of South Africa in a rural context.

Small Businesses and Entrepreneurial Environment

In a country such as South Africa where employment is dismally low (OECD, 2013), with roughly 27% rate of unemployment (Statistics South Africa, 2012), young economically active population still face the mounting issues of unemployment. The best means to address the challenges of unemployment in South Africa is to stimulate employment opportunities through small businesses development (Fin Mark Trust, 2006). However, in the area of early-stage entrepreneurial activities, there are glaring indications that South Africa lags behind (GEM, 2011). Despite some improvement in 2009, the TEA rate of 5.9% to 8.9% in 2010 and the country’s average for efficiency-driven economies stands at 11.7% in contrast to other developing countries.

In 2008, South African TEA ratings showed10.6% below the average expectations which translates to a position of 23rd out of 43rd participating countries in the research (Herrington et al., 2009). Given these high failure statistics regarding entrepreneurship and small businesses in South Africa, new venture formation serves as the best replacement to the high rates of small businesses failures (Gree & Thurnik, 2003). Supporting this notion, available literature suggests that globally, South Africa experience significantly high rate of small businesses failures. Von Broembsen et al. (2005) agreed that an estimate of 75% newly established small businesses failed. Brink et al. (2003) affirm that roughly, between 70% and 80% small businesses failed in South Africa. As such, it is unlikely that new small businesses to survive beyond 42 months in South Africa as compared to various sampled countries as participants in the Gem study. Further Gem study indicates that start-ups in South Africa hardly survive and that the opportunity for entrepreneurial activities is at its lowest in contrast to other developing countries Department of Trade and Industry (DTI, 2008).

Researchers, Ligthelm & Cant (2002) stated that some of the underlying causes of high business failure rates as managerial, financial, marketing and human resource challenges. Sha (2006) in another study pointed to obstacles of environmental, financial and managerial issues as contributors. On the other hand, Noor et al. (2012) mentioned lack of critical resources such as knowledge, experience and educational skills as primary causes to small businesses and entrepreneurship failure. According to Marshall & Oliver (2005), lack of knowledge, skills and inadequate social network contribute to the persistent failures.

Entrepreneurship drives and enhances economic processes in developing countries to shift potential ideas into commercial opportunities (Melicher, 2009). Thus, entrepreneurship is an action-driven phenomenon that promotes opportunities (Sikalieh et al., 2012). In spite of its socio-economic benefits, entrepreneurial activities struggle to survive especially in rural areas. Entrepreneurial activities as defined, lack enough social networks and information flow to remain competitive (Brand, Du Preez & Schutte, 2007). As stated by researchers, Janse van Rensburg (2011) supported by a recent SME Survey (2010), growing crime rates and lack of shift in technology by owner-managers severely impedes entrepreneurial activities. Recent survey commissioned by the Centre for Development Enterprise (CDE) (CDE, 2007) and the DTI (2008) postulates several impediments including high crime rates, lack of infrastructure, unstable regulatory framework, and negative perception towards entrepreneurial activities as vital drawbacks to small businesses and entrepreneurial activities.

Several scientific works were on record that the general lack of owner-manager’s ability to prepare credible business plans in exchange for financial support equally hampers entrepreneurial activities (Ehlers & Lazenby, 2007; Rwigema, 2004). In most emerging countries including South Africa, entrepreneurial activities and business operations becomes impossible due to the harsh realities of bureaucratic issues and market limitations (Rankhumise, 2010; Bennett, 2008). It is generally agreed that small businesses are unable to access basic infrastructure such as water and energy supplies as well as lack the support of service providers (Fatoki & Garwe, 2010; Bowen et al., 2009).

Entrepreneurial activities in the global context cannot be successful in weak legal environments. Recent World Bank (2007) study indicates that the regulatory environment including the South African labour laws continue to be highly unfriendly in contrast to existing OECD labour legislations. Chilone & Mayhew (2010) agree that the severity of South Africa’s regulatory system represents unfair labour practices; hence posing serious challenges to owner-managers. Several authors including Adcor (2012) and Naqvi (2011) add that entrepreneurial activities are marred by various challenges. For instance, for decades, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) reports revealed poor managerial skills among owner-managers because of reduction in skills training being the critical contributors to small business challenges.

The growing lack of organisational knowledge by owner-managers is seen as vital challenges to entrepreneurial activities (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). Furthermore, Lau & Busenitz (2001) add that unpreparedness by owner-managers add to limitations of small business operations. Other researchers are of the view that owner-managers lack financial and accounting skills to smoothly operate small businesses (Herrington et al., 2008; Fourie et al., 2004). Empirical studies have shown that owner-managers of small businesses are not knowledgeable of government services (Herrington et al., 2010). Prior researchers Berlin et al. (2010) support the views that owner-managers are unable to source “seed capital” as equity from friends and family members, lack managerial skills and inadequate training (Shejavali, 2007). Given the general literature review regarding the challenges, the study put forward the following alternative hypotheses:

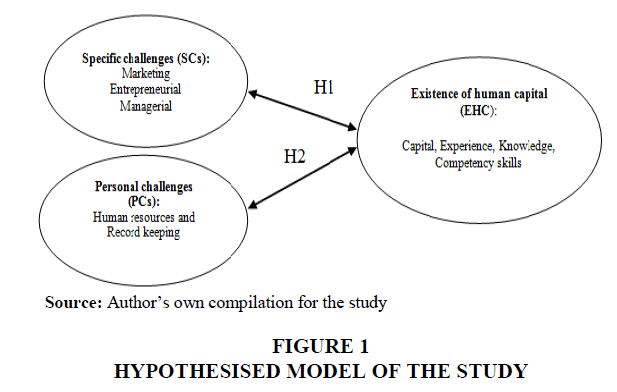

H1A Specific challenges (SCs) (marketing, environmental and managerial) are correlated with the existence of human capital (EHC).

H2A Personal challenges (PCs) (human resources and record keeping) are correlated with the existing of human capital (EHC).

Human Capital and Entrepreneurship

Several studies have been used to explain human capital and entrepreneurship. By definition, human capital entails acquiring potential skills such as individuals’ knowledge, and experiences applicable during entrepreneurial activities for developmental benefits (Hessels & Terjesen, 2008). Drawing from the Resource Based Theory (RBT), human capital represents vital source of competitive advantages during entrepreneurial activities. As indicated by Ganotakis (2012), the knowledge and skills acquired by individuals represent varying forms of investment capital. Investments opportunities in human capital according to Schultz (1970), leads to productivity and higher returns. This implies that any society with high entrepreneurial activities have the potential to establish significant economic growth (Ahmad et al., 2010; Noor et al., 2012).

The theory of Human capital advances key resource base on different forms of employment opportunities including entrepreneurship. This adds to the existing notion that individuals who are gifted with higher stock of human capital in terms of knowledge and skills easily add to economic potentials and values (Nahapiet, 2011). Acquiring the right resources in combination is only possible through skills training, education as well as the wealth of experience (Jones et al., 2010; Mosey & Wright, 2007; Shrader & Siegel, 2007; Serneels, 2008). Recent study by Smith & Perks (2006) confirms the significance of human capital in enabling owner-managers to obtain several interpersonal skills. This further implies that more can be achieved through human capital as individuals invest largely in education and training. According to Von Krogh & William (2011), there is relationship between time spent during the period of education and earnings. Researchers are of the opinion that formal education creates employment for individuals; as such qualifications through formal education is regarded as investment in individuals to secure employment (Blundell et al., 2005; Currie & Almond, 2009). However, Nahapiet (2011) argued that formal education creates limitations.

For decades, owner-managers of small businesses are able to portray high entrepreneurial qualities because of built in resources due to education and the dearth of individual experiences (Gibb, 1996). This notion support Schumpeter’s theory of “creative destruction” which stems from activities of education and economic restructuring. The theory emphases that there is strong association between entrepreneurial activities and human capital (Teece, 2011). Individuals’ talent of creativity or to make sense of available opportunities within the environment largely depends on human capital. The stock of human capital in the form of previous business experiences is of highly significant as it permits the general creation of tangible assets that links owner-managers with several stakeholders (Shaw, Lam & Carter, 2008; De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; Delmar & Shane, 2004). In essence therefore, Monks (2010) argued that access to financial reserves create severe impediments to entrepreneurial activities in both the developed and developing countries.

Research Framework and Applicable Variables

The research framework that underpins this study is based on several national and international studies in the context of rural entrepreneurial challenges. The framework is used to formulate hypotheses to be tested based on independent variables. Furthermore, EFA was performed to divide the constructs of SCs and PCs. However, it was not applied in relations to human capital since it entails only the related questionnaire items (statements). As far as the two constructs of SCs and PCs are concerned, the KMO tests as shown in Tables 4 and 6 (p-values=0.000) demonstrated that it was plausible to represent set of questions by few constructs (latent factors) index. Based on Cronbach alpha results, the author the variables or research items that loaded sufficient ranging from 0.60 to 0.70 (Hair et al., 2006). In the survey, only items (statements) that conform to the rule above constituted part of the study. Besides other analytical tools of BTS and KMO, the Verimax rotation was also utilised to lessen the number of factors per item since it becomes desirable that each item belongs to exactly one factor.

Figure 1 on the following page illustrates key variables that this study investigated. The model constitutes two main independent dimensions, namely the SCs and PCs and how they influence the main dependent dimension; the EHC. In order to analyse the challenges that are faced by owner-managers, the independent variables SCS and PCs are explained in detail.

The measurement constructs for SCs, PCs and EHC formed part of the questionnaire for this study. Every construct had several items (statements) which were summarised into an index (latent factor) to represent the intended variable. The construct of EHC focuses on individual descriptor-items such as “Knowledge, Capital, Experience, Competency and skills”. These items (statements) were sourced from extant literature of human capital theory. Ten questionnaire items (statements) were extracted from knowledge whilst the rest had five items each. Equally, the construct of SCs had fifteen questionnaire items (statements) which were subdivided into four sub-constructs using EFA (Table 4). The construct of PCs on the other hand constitutes ten items of the questionnaires (statements). These items were subdivided into two sub-constructs through the EFA as depicted in Table 6 below. The preceding sections provide sufficient explanations of the two primary constructs of SCs and PCs respectively.

Operationalizing the Primary Constructs

A Table 4 below depicts varimax-rotated factor loadings of SCs. The analysis generated four factors considered representative enough to be used in analysing SCs to ensure adequate outcomes. Four factors namely marketing, entrepreneurial, managerial and financial challenges with eigenvalues greater than one accounted for 75.6% of the total variation of SCs. Taking the eigenvalue rule into account, only the factor “financial challenges” with factor loadings greater than 0.35 on a particular factor were significant and deemed to belong to the particular factor (sub-construct). Items of financial challenges with factor loadings less than 0.35 were excluded (Leech et al., 2005; Field, 2013).

Likewise, Table 6 shows compilation through the rotated component matrix of PCs. From the analysis thus far, two factors namely “management”, “education and training” have emerged. These factors were considered by the author to be representative enough during the analyses stages for stated scientific outcomes and in line with descriptions of literature. Based on eigenvalue account, the two factors “management”, education and training showed high factor loadings more than 0.35 (Leech et al., 2005; Field, 2013).

To ensure maximum clarifications, this study operationalised EHC as investment in employees’ education and training, competency, previous knowledge, learning experiences, availability of social skills, collaboration with others, motivation and resourcefulness, business experience and family background.

As shown in Figure 1 below, two primary constructs of SCs and PCs were shown in the schematic model of the conceptual framework to determine influences on EHC. This model illustrates the linkages of the variables namely SCs and PCs in rural settings; thus, the model provides the primary tool to develop the alternate hypotheses to be tested.

As indicated in the schematic model of the conceptual framework, two variables were used to determine the influence of EHC. This schematic model illustrates the linkages among the challenges of SCs and PCs in rural settings. Thus, the schematic model (Figure 1) provides the core basis to develop the research hypotheses.

Methodology

Sample and Sampling Method

In order to empirically achieve the study objectives, 300 owner-managers of small businesses were initially identified to gather primary data through the simple random sampling approach. This approach enable the author to achieve the desired sampling frame, easy to use, avoid bias during the selection process and to attain enough sample representations (Van Vuuren & Maree, 1999; Strydom & Delport, 2011). In order to construct reliable research sample, the author utilised the lottery approach to select owner-managers based on the sample frame. To ensure accurate selection of 300 owner-managers, their names from the research settings were written on cards, placed in a plastic bowl and hand-picked through the lottery approach. Owner-managers who took part in the study were individuals who currently operate entrepreneurial activities. However, the educational qualifications and skill levels remain very low. Two criteria were used; only owner-managers who operate entrepreneurial activities in the study areas were allowed to provide data for the study. Secondly, only owner-managers of small businesses who operate in the study areas for over 2 years with employment capacity of between 5-50 persons are allowed to participate in the study. Out of the total research instrument of 300 questionnaires, 282 were completed and returned for analysis with a response rate of 94%. The remaining owner-managers were unable to provide data citing specific personal issues that contributes to their inability to fully participate in providing data.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

In this study, SCs and PCs were recorded and assessed on a 7 Likert-scale in order to determine owner-‘managers’ perceptions regarding the challenges. Employing the Likert-scale in this study is justified since it measures high levels of internal reliability of applicable constructs throughout the study (Ho & Koh, 1992). Higher scores by owner-managers on the Likert-scale in this study meant higher level of agreement to each questionnaire items (statement). The 7 Likert-scale allow responses to questionnaires items (statements) to be measured as follows: 1 “strongly disagree” through to 7 “strongly agree” (Maree, 2007).

The measuring instrument for this study is divided into different sections. Section A consisted of 15 related items (statements) which were carefully selected from literature to describe SCs. Through the 7 Likert-scale, owner-managers of small businesses were asked to rate each statement either as 1=strongly disagree through to 7=strongly agree. Section B on the other hand, is designed as measurement for 10 items (statements) relating to PCs. Owner-managers of small businesses were asked to rate these items (statements) according to individual perceptions and as interpreted on the 7 Likert –scale (1=strongly disagree through to 7=strongly agree). Included in the measuring instrument were demographic variables such as age, sex, marital status, gender, race and educational qualifications of owner-managers. As part of the 7 Likert-scale was the section on business and operational information with options from which owner-managers were required to select most suitable options. Business information includes business locations in the municipality, daily average business hours per week, number of full/part-time employees, age classification of small businesses, market location of products/services among others.

Completed questionnaires that were received went through varying analytical strengths including descriptive analysis; the means and standard deviation to determine the general levels of agreement or disagreement to pose specific questions. Further inferential statistics were conducted to evaluate the model demonstrated in figure 1 below for hypothetical assessment.

Data for the study was statistically analysed by means of IBM-SPSS Version 23. The analyses were based on 282 usable questionnaires from owner-managers. The measuring instrument of the study was subjected to EFA and the Cronbach-alpha Coefficient in order to assess validity and reliability of the study. Besides, the Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient was calculated to determine the relationships between SCs, PCs and the EHC. The descriptive statistics aided by the mean and standard deviation were employed to summarise the sample distribution.

Throughout the analytical phase, owner-managers were asked to state their responses based on values on a 7-point Likert-Scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”. This means that lower scores represent relative minimal challenges while higher scores on the scale represent high level of challenges. Higher mean scores by owner-managers mean that the overwhelming majority agreed that either SCs or PCs impede negatively on entrepreneurial activities and small businesses.

Sample Profile

This study took place in the NCP of South Africa, precisely in two rural district municipalities of FB and JTG. The population of the study include owner-managers of small businesses from the two municipalities. However, due to lack of credible database, the author decided to use a sampling frame of 300 owner-managers through the simple random sampling approach (Van Vuuren & Maree, 1999).

Results from demographic profile of the sample showed that majority (53.90%) of participating owner-managers were Black South Africans. The Coloured South Africans consisted of 10.99%; while the Indian owner-managers were 9.92%. In this study, only 5.3% of participating owner-managers were Whites. Out of the study, 179 were male and 100 were female participants. As far as age distribution is concerned the majority (40.07%) were in the 40-49 years age group while the second largest (33.33%) age group of owner-managers were between the 30-39 years grouping. Regarding education, 23.05% of owner-managers received matric certificates as the highest educational qualifications in the two district municipalities; 22.70% attained below matric certificates only few (0.57%) owner-managers were able to receive trade skills training. However, a sizeable number of 7.09% owner-managers were university graduates. Majority (51.77%) of the owner-managers were in a steady relationship across the district municipalities.

Validity and Reliability of Measuring Instrument

Throughout every scientific study, it is essential to validate the measuring instrument. During this study key statistical tools such as EFA supported by BTS and KMO formed part of the main extraction and rotation methods. A total of seven different factors including SCs, PCs and EHC were loaded through the EFA. These factors explained altogether are made up of 46% variance as indicated in the data. Through the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, reliability of measurement instrument was tested. According to Haron (2010), in line with social science standard, the cut-off point is set at .70 or more for questionnaire items to form part of the scale. In this study, the Cronbach-alpha Coefficients with values greater than 0.70 were calculated for all construct indicating significant reliability of the measuring scales (Nunnally, 1994). However, in this study not all the factors have attained the stated values as required by the rules.

Empirical Results

Data summary was conducted in this section. Descriptive statistics as stated in Tables 1-3 aided by mean scores and standard deviations were applied in analysing the data based mainly on SCs and PCs of entrepreneurial activities and small businesses. Besides, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the relationship between the independent variables of SCs and the PCs on the dependent variable; the EHC. Earlier in this study, the EFA was applied to determine excerpt of relevant factors that were considered representative enough to be analysed based on the dependent and independent variables in line with the BTS and KMO as explained.

| Table 1 Descriptive Statistics Of SCS | ||||

| Variables | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| Poor education system | 6.014 | 1.577 | -2.161 | 3.772 |

| Lack of skilled employees | 5.881 | 1.466 | -1.815 | 2.744 |

| Problem of start-up capital | 6.388 | 0.869 | -2.919 | 13.739 |

| Inadequate basic infrastructure (roads, transportation, electricity) | 4.039 | 2.212 | -0.056 | -1.619 |

| Difficult regulatory and policy measures | 5.011 | 1.589 | -0.591 | -0.543 |

| Insufficient marketing information and opportunities | 5.642 | 1.539 | -1.495 | 1.481 |

| Local economic development does not focus on small businesses | 6.335 | 1.091 | -2.693 | 8.381 |

| Absence of small business education | 6.366 | 0.891 | -2.570 | 10.086 |

| Lack of general small business support by government | 6.434 | 0.810 | -2.501 | 9.930 |

| Too much costs of doing business | 6.348 | 0.896 | -2.072 | 5.671 |

| Lack of support from the local district municipality | 6.460 | 0.970 | -2.816 | 9.353 |

| High crime rates | 5.584 | 1.740 | -1.324 | 0.719 |

| Lack of competition | 3.478 | 2.283 | 0.280 | -1.569 |

| Problems with suppliers | 4.000 | 2.323 | -0.100 | -1.629 |

| Inability to prepare credible business plans for bank loans | 5.444 | 1.619 | -0.847 | -0.252 |

| Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of PCS | ||||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Lack of self-confidence | 2.809 | 2.134 | 0.838 | -0.996 |

| Great fear of business failure | 4.727 | 2.229 | -0.573 | -1.327 |

| Pressure due to extended family responsibility | 4.239 | 2.149 | -0.095 | -1.615 |

| Lack of education and general training | 5.879 | 1.437 | -1.999 | 3.720 |

| Lack of small business success stories and role models | 4.854 | 1.936 | -0.527 | -1.067 |

| Time pressures because of work and family issues | 4.550 | 2.030 | -0.348 | -1.439 |

| Lack of permanent business office | 4.580 | 2.232 | -0.393 | -1.557 |

| Problem of running the business alone (no family support) | 4.264 | 2.239 | -0.070 | -1.662 |

| Unable to understand existing tax policies | 4.943 | 2.200 | -0.618 | -1.236 |

| Not able to use internet services for marketing opportunities | 5.638 | 1.765 | -1.559 | 1.268 |

| Table 3 Descriptive Statistics of the EHC | ||||

| Existence of Human Capital (EHC) | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| The business has experienced growth in employees (we employed more people) over the past few years |

3.582 | 2.029 | 0.145 | -1.674 |

| People working in the business (employees, but also the owner-manager) are highly committed to make a success of the business | 5.687 | 1.496 | -2.237 | 4.233 |

| People working in the business (employees) are viewed as the most valuable asset of the business | 5.309 | 1.814 | -1.510 | 0.913 |

| The morale (job satisfaction) of our employees (included the owner-manager) has improved over the past few years | 4.911 | 1.963 | -1.060 | -0.393 |

| The business keeps most of the employees over the years (they are working many years for the business) | 4.090 | 2.054 | -0.345 | -1.544 |

| Employees do not want to leave the business and work for another business | 4.171 | 2.123 | -0.340 | -1.561 |

Table 1 above depicts the mean scores of SCs as perceived and ranked by owner-managers of small businesses. The overall results according to the Table 1 have shown that seven out of the fifteen SCs were ranked with the mean scores above 6.00. Five were ranked a little above the mean of 5.00; only three of the SCs were perceived by owner-managers below the mean of 5.00. These imply that majority of owner-managers perceived stated items significantly influenced entrepreneurial activities and small business operations in a negative way. Given these mean scores, the standard deviation of the bulk questionnaire items on SCs revealed fairly high values from 0.869 to 2.323 on the scale.

The above Table 2 shows the mean scores of PCs according to owner-managers’ level of responses to the items on the questionnaire. From the table, two items out of 10 were ranked with mean scores slightly above 5.000. Only one item “lack of self-confidence” was ranked at a mean score of 2.809. However, majority were scored by owner-managers above 4.000; indicating that there was overwhelming agreement by most of the owner-managers that the bulk of PCs items as defined influence negatively on level of entrepreneurial activities and small businesses operations. Based on the mean scores, the standard deviation of the items on the questionnaires show fairly high values ranging from 1.437 to 2.239.

Six items of EHC as indicated on the questionnaires were designed to determine the significance of EHC in operating small businesses as part of the entrepreneurial activities. Owner-managers were required to rank each item as in line with the scale descriptions. From the total items (Table 3), one item “the business has experienced growth in employees (we employed more people over the past few years)” was scored below the mean of 4.000. Two similar items were scored above the mean of 5.000 in contrast to the remaining scored more than mean of 4.000. Given from the overall fairly high mean scores by owner-managers, it can be firmly stated that EHC influence owner-managers. As such, EHC impact on entrepreneurial activities and small business operations.

As shown in the model (Figure 1), the study is designed to determine correlation between SCs regarding marketing, managerial challenges and EHC. Further focus was to determine the correlation between PCs namely human capital, record keeping and EHC. The primary was to determine whether EHC increase or decrease as SCs (Tables 4 & 5; managerial and marketing challenges) increases. Also to determine whether increase in PCs (human resources and record keeping challenges) increases or decreases in EHC.

| Table 4 Rotated Component Matrix of SCS | ||||

| Marketing | Entrepreneurial | Managerial | Financial | |

| Inadequate basic infrastructure (roads, transportation, electricity) |

0.827 | |||

| Difficult regulatory and policy measures | 0.734 | |||

| Lack of competition | 0.758 | |||

| Problems with suppliers | 0.761 | |||

| Inability to prepare credible business plans for bank loans | 0.707 | |||

| Local economic development does not focus on small businesses | ` | 0.704 | ||

| Absence of small business education | 0.676 | |||

| Lack of general small business support by government | 0.729 | |||

| Lack of support from the local district municipality | 0.741 | |||

| Poor education system | 0.765 | |||

| Lack of skilled employees | 0.803 | |||

| Insufficient marketing information and opportunities | 0.454 | |||

| Problem of start-up capital | 0.689 | |||

| Too much costs of doing business | -0.422 | |||

| High crime rates | -0.584 | |||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.825 | 0.695 | 0.524 | -0.036 |

Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

| Table 5 KMO and Bartlett's test for SC | ||

| Kiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.778 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 995.017 |

| df | 105 | |

| P-value | 0 | |

Personal Challenges Factors (PCs)

From Table 6 below, PCs depicts latent factors and questionnaire items with loadings greater than 0.35 on either of the two factors that were deemed to belong to specific factor. Majority of the factor loadings accounted for by the two PCs factors were greater than 0.7; this is evidence of an excellent factor structure with well-defined factors. The Bartlett test of Sphericity (BTS) and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test (Tables 5 & 7: p-value=0.000) shows that it is appropriate to provide detailed summary of the questionnaire items (statements) that are under PCs into the two listed factors.

| Table 6 Rotated Component Matrix of PCS | ||

| Management | Education and Training | |

| Lack of self-confidence | 0.597 | |

| Great fear of business failure | 0.757 | |

| Pressure due to extended family responsibility | 0.717 | |

| Lack of small business success stories and role models | 0.690 | |

| Time pressures because of work and family issues | 0.707 | |

| Lack of permanent business office | 0.783 | |

| Problem of running the business alone (no family support) | 0.709 | |

| Unable to understand existing tax policies | 0.788 | |

| Lack of education and general training | 0.789 | |

| Not able to use internet services for marketing opportunities | 0.770 | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.873 | 0.490 |

Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

| Table 7 KMO and Bartlett's test for PC | ||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.832 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. chi-Square | 1066.268 |

| Df | 45 | |

| p-value | 0.000 | |

Composition of EHC Factors

The EHC factors are composed of one factor with six items (statements) as shown in Table 8. The loadings of this factor are fairly high with only one item (statement). However, the factor “people working in the business are highly committed to create successful business” was dismally low with factor loading of 0.474. The Barlett test of Sphericity (BTS) and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test (Table 9: p-value=0.000) shows that it is proper to summarise this construct with one latent factor.

| Table 8 Rotated Component Matrix of EHC | |

| Existence of Human Capital | Human Factor |

| The business has experienced growth in employees (we employed more people) over the past few years | 0.746 |

| People working in the business (employees, but also the owner manager) are highly committed to create successful businesses. | 0.474 |

| People working in the business are viewed as the most valuable assets. | 0.752 |

| The morale (job satisfaction) of our employees (included the owner manager) has improved over the past few years | 0.833 |

| The business keeps most of the employees over the years (they are working many years for the business) | 0.877 |

| Employees do not want to leave the business and work for another business | 0.810 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.852 |

| Table 9 KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.837 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 739.410 |

| Df | 15 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

Relationships between SCs and Human capital

Based on the results in Table 10 below, the following observations were made. The Pearson correlation examined the relationship between SCs in terms of marketing challenges and EHC. Results showed negative correlation, weak and significant (r (260) = -0.330, p-value=0.000). It seems there was an increase in marketing challenges has a slight decrease in EHC. The result implies a slight negative relationship on EHC. The Pearson correlation was used to examine the relationship between SCs in terms of environmental challenges and EHC. The correlation revealed positive, negligible and not significant (r (261) = -0.074, p=0.237. The result showed SCs in terms of environmental challenges appear to show no significant relationship between EHC. Thus, it seems an increase in environmental challenges have no relationships of EHC. The Pearson correlation examined the relationship between SCs in terms of managerial challenges and EHC. The correlation showed positive negligible not significant (r (260) =0.045, p-value=0.467). Thus, it seems an increase in managerial challenges has no effect on EHC. Accordingly, managerial challenges have no impact on EHC.

| Table 10 Correlations Between SCS and EHC | ||||

| Marketing | Environmental | Managerial | ||

| Environmental | Correlation | -0.191** | ||

| p-value | 0.002 | - | ||

| N | 265 | |||

| Managerial | Correlation | 0.080 | 0.266** | |

| p-value | 0.195 | 0.000 | - | |

| N | 266 | 269 | ||

| Human Capital | Correlation | -0.330** | -0.074 | 0.045 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.237 | 0.467 | |

| N | 260 | 261 | 264 | |

Relationships between PCs and the EHC

The Pearson correlation is used to examine relationship between Pcs in terms of human resource challenges and EHC. The relationship was negative, weak in strength and statistically (r (264)=-0.365, p-value=0.000). It seems an increase in Pc in terms of record keeping thus resulting in a slight decrease in the EHC. Thus, PCs in terms of human resource challenges has a slight negative impact on EHC. A Pearson correlation examined the relationship between record keeping (PC) challenges and EHC. The relationship was negative, weak in strength and statistically significant (r (268) =-0.231, p-value =0.000). It seems that an increase in PC in terms of record keeping results in a small decrease in the EHC. Hence record keeping has a slight negative impact on the EHC (Table 11).

| Table 11 Relationships Between PCS and EHC | |||

| Human resources | Record Keeping | ||

| Record keeping | Correlation | 0.282** | |

| p-value | 0.000 | - | |

| N | 273 | ||

| Human Capital | Correlation | -0.365** | -0.231** |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 264 | 268 | |

Discussion

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the influence of SCs and PCs on EHC of entrepreneurial activities and small businesses. Besides, the study aims to test the relationships between SCs and PCs on EHC of entrepreneurial activities. The final outcomes of this empirical survey confirmed that key challenges of different dimension continue to impede entrepreneurial activities in the research settings. In general, the findings revealed that owner-managers experience severity of SCs as well as PCs. Though owner-managers scored high a number of individual challenges to have significant influence on entrepreneurial activities and small business operations, this empirical survey found diverse number of growing challenges that surfaced throughout the study no matter the existing operational environment.

From the onset, descriptive statistics were conducted in search of solutions in line with the stated objectives. Regarding SCs, majority of owner-managers scored significantly high some of the challenges through the Likert-Scale. Once more these findings were another clear demonstration of inability of owner-managers of small businesses to obtain adequate form of education which hinder owner-managers’ level of competencies (Kondowe, 2013). Out of 15 items that defined SCs only one was scored below the mean value of 4.000. This implies that the remaining items were not only scored significantly high through the mean statistics but also indications that majority of owner-managers agreed that SCs constraint small business operations. These findings are consistent with previous scientific literature by Loué & Baronet (2012) and Wasdani & Mathew (2014) found that specific challenges such as opportunity search, business recognition and exploitation impede small businesses. Chua et al. (2011) confirmed that due to their small sizes, owner-managers are unable to utilise specific tools such as social capital for business success. Another scientific literature by Piperopoulos (2010) support the present findings that rural communities find it very difficult to operate small businesses since they only make use of scarce social resources. Rogerson (2006) in an earlier study confirmed that SCs such as the markets and marketing information largely influence in negative ways business operations of owner-managers.

The Pearson correlation was employed to determine the relationship between the variables (Figure 1). The final outcomes revealed several yet related challenges. Regarding the SCs and EHC, the study indicated that EHC does not depend on SCs or on managerial challenges. This implies that expectations of EHC are less substantial that could be anticipated through the influence of other variables. In contrast, the Pearson correlation found marketing challenges to have influence on EHC of entrepreneurial activities. This finding is consistent with previous study by Rogerson (2006) that outlined the significant influences of market and marketing information on operations of small businesses and entrepreneurial activities. Considering owner-managers responses, the outcomes of Pearson correlation suggests that there is the need for more focus on education (Fatoki & Garwe, 2010). This revelation further suggests that for entrepreneurial activities to be successful, investment in rural education must be prioritised and intensified.

Similar to findings on SCs, this empirical study revealed varying challenges in terms of PCs’ negative influence on small business operations and entrepreneurial activities. Further revelations through the Pearson’s correlation results found two dominant variables. These variables include “human resource challenges” and “record keeping”. Reasons that underscore the findings could be due to the minimal level of education and training by owner-managers across the research settings. This is consistent with past scientific studies that show over the years, the essential of education and training to generally enhance small business operations (Schachtebeck, 2018; Lekhanya, 2015; Mazanai & Fatoki, 2012; Herrington et al., 2010).

Management Implications

Data for this study is empirically gathered to reflect the SCs and PC. The findings are expected to add value to existing field of rural entrepreneurial activities and small businesses. Thus, the outcomes suggest rural-based strategies to curb these challenges and craft workable and applicable rural-based management actions. The empirical study was a thinly pursued area within the context of the sample size of small businesses; the final outcomes are most likely to be useful to local management practitioners.

This study outlines the following basic management implications:

? Theoretically, this study provides and assesses a hypothesised model to investigate the influence of SCs and PCs on EHC of entrepreneurial activities and small businesses.

? The influence of SCs and PCs and EHC of the entrepreneurial activities and small businesses.

? The present empirical findings add value to extant literature by providing enough information regarding rural entrepreneurship and small businesses.

Given the empirical outcomes, specific management actions should be taken to address specifically the marketing and record keeping challenges as revealed by the study. Others include the provision of management skills to support owner-managers (ILO, 2009).

Limitations and Future Research

There is no scientific study without limitations. The current empirical study was limited to few small businesses in two local municipalities in the NCP of South Africa. As such, this study provides sufficient opportunities to conduct future study. In view of these, the author caution that a more cautious approach be taken during stages of application and interpretations of the empirical-based outcomes. Furthermore, additional care should be applied in generalisation the empirical findings across provinces or country-wide. Given the outcomes of this study, future scientific work should be undertaken in qualitative terms to understand how SCs and PCs can create positive influences on small business operation and enhance entrepreneurial activities in rural settings. In addition, more research should be conducted to determine how EHC can be used to curtail negative influences of PCs on small businesses and entrepreneurial activities. Applying descriptive statistics in this empirical study provides enough understanding of key challenges. However, the level of statistical evaluations is limited to pronounce the causes of the challenges. Given these limitations, future empirical study should focus on causation.

Conclusion

This study which was founded on the theme “Investigating the influence of SCs and PCs on existence of human capital of rural entrepreneurial activities and small businesses: managerial implications”, sort to determine the degree of challenges faced by owner-managers. In conclusion, this empirical survey revealed that in terms of SCs, few outstanding variables emerged as critical impediments. These include poor education system; local economic development does not focus on small businesses, absence of small business education, no priority for small businesses, lack of support for small businesses by government, too much costs of doing business, lack of support from local district municipality, high crime rates and inability to prepare credible business plans for bank loans.

In terms of PCs, the study concluded that key influential variables such as lack of education and general training, not able to use internet services for marketing opportunities, unable to understand existing tax services, great fear of business failure, lack of small business success stories and role models, lack of permanent business office and time pressures because of work and family issues play critical roles in influencing small business operations and entrepreneurial activities. The EHC is scientifically proven to enhance business operations. Supporting this claim, owner-managers indicated through their responses that key variables of poor working in the business (employees but also owner-managers) are highly committed to make the business to be successful, people working in the business (employees) are viewed as the most valuable assets of the business, the moral (job satisfaction) of our employees (including owner-managers) has improved over the past few years and employees do not want to leave the business and work for another business.

For further realisation of stated objectives, the author formulated alternate hypotheses that were tested through the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Based on owner-managers’ responses to questionnaire items on SCs, PCs and EHC, the study found that owner-managers are faced with various challenges involving the two variables. Besides, majority of the owner-mangers stated that for small businesses to be successful, it is fundamental that there is adequate human capital. These findings emerged from the mean scores of owner-mangers. However, further analysis revealed that PCs are more influential in contrast to SCs. Regarding the existence of EHC, the outcomes showed that majority of owner-managers strongly perceived availability of human capital very critical in small businesses successful operations and an enhancement to entrepreneurial activities. To ensure that stated hypotheses were tested, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient is applied. Though the study revealed that SCs and PCs are very influential on the EHC of entrepreneurial activities, further revelation showed that PCs exert more negative influence than SCs.

References

- Adcor, P. (2012). New business start-ups slump to all-time low.

- Agyapong, D., Agyapong, G.K., & Darfor, K.N. (2011). Criteria for assessing small and medium enterprises’ borrowers in Ghana. International Business Research, 4(4), 132-138.

- Ahmad, N.H., Halim, H.A., & Zainal, S.R.M. (2010). Is entrepreneurial competency the silver bullet for SME success in a developing nation. International Business Management, 4(2), 67-75.

- Ahmad, S.Z., & Xavier, S.R. (2012). Entrepreneurial environments and growth: evidence from Malaysia GEM data. Journal of Chinese Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 50-64.

- Aldrich, H.E., & Fiol, C.M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of management review, 19(4), 645-670.

- Bennett, R. (2008). SME policy support in Britain since the 1990s: what have we learnt?. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 26(2), 375-397.

- Berlin, A., Doherty, F., Garmise, S., Ghosh, S. A., Moorman, N., Sowders, J., & Texter, M. (2010). International Economic Development Council (IEDC). Unlocking entrepreneurship: a primer for economic developers.

- Blundell, R., Dearden, L., & Sianesi, B. (2005). Evaluating the effect of education on earnings: models, methods and results from the national child development survey. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 168(3), 473-512.

- Bosma, N., & Levie, J. (2010). Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2009 global report.

- Bowen, M., Morara, M., & Mureithi, M. (2009). Management of business challenges among small and micro enterprises in Nairobi-Kenya. KCA Journal of Business Management, 2(1), 16-31.

- Brink, A., Cant, M., & Ligthelm, A. (2003). Problems experienced by small businesses in South Africa. In 16th Annual Conference of Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand.

- CDE. (2007). Young Soweto entrepreneurs. Retrieved from https://www.cde.org.za/young-soweto-entrepeneurs-organising-for-small-business-advocacy/

- Chimucheka, T., & Rungani, E.C. (2011). The impact of inaccessibility to bank finance and lack of financial management knowledge to small, medium and micro enterprises in Buffalo City Municipality, South Africa. African Journal of Business Management, 5(14), 5509-5517.

- Chua, J.H., Chrisman, J.J., Kellermanns, F., & Wu, Z. (2011). Family involvement and new venture debt financing. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), 472-488.

- Currie, J., & Almond, D. (2011). Human capital development before age five. In Handbook of labor economics. Elsevier.

- De Carolis, D.M., & Saparito, P. (2006). Social capital, cognition, and entrepreneurial opportunities: A theoretical framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 41-56.

- Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2004). Legitimating first: Organizing activities and the survival of new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(3), 385-410.

- DTI-Department of Trade and Industry. (2008). Annual review of small business in South Africa - 2005-2007. Enterprise development unit. Pretoria: Department of Trade and Industry. Retrieved from https://pdf4pro.com/file/82f53/sme_development_docs_3_Annual_Review_Final_Report_11_Aug_08.pdf.pdf

- Ehlers T. & Lazenby, K. (2007). Strategic Management. South African and Cases, 2nd edition, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. sage.

- Fin Mark Trust. (2006). Fin scope small business survey report. Retrieved from http://www.finmark.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/FS-Small-Business_-reportFNL2.pdf

- Fourie, L., Mohr, P., & Fourie, L. (2004). Economics for South African students. Van Schaik Publishers.

- Ganotakis, P. (2012). Founders’ human capital and the performance of UK new technology based firms. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 495-515.

- GEM. (2011). Global entrepreneurship monitor. Retrieved April 20, 2019, from http://www.gemconsortium.org

- Gibb, A.A. (1996). Entrepreneurship and small business management: can we afford to neglect them in the twenty?first century business school?. British Journal of Management, 7(4), 309-321.

- Gree, A., & Thurnik, C. (2003). Firm selection and industry evolution: the post country performance of new firm. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 4(4), 243-264.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Uppersaddle River.

- Haron, H. (2010). Research Methodology. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia.

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., & Kew, P. (2008). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2008 South African Report. Cape Town: Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town.

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., & Kew, P. (2009). Global entrepreneurship monitor, South African report. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., Kew, P., & Monitor, G.E. (2010). Tracking entrepreneurship in South Africa: A GEM perspective. South Africa: Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town.

- Hessels, J., & Terjesen, S. (2008). Entrepreneurial career capital, innovation and new venture export orientation. Scientific Analysis of Entrepreneurship and SMEs, SMEs and Entrepreneurship Programme financed by the Netherlands Ministry of Economic Affairs, The Hague.

- ILO (International Labour Organisation). (2009). The informal economy in Africa: Promoting transition to formality: Challenges and strategies. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/emppolicy/pubs/WCMS_127814/lang--en/index.htm

- Janse van Rensburg, Y. (2011). Labour provides the greatest hindrance to SME growth.

- Jones, O., Macpherson, A., & Thorpe, R. (2010). Learning in owner-managed small firms: Mediating artefacts and strategic space. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(7-8), 649-673.

- Kondowe, C. (2013). Exploring the circumstances and experiences of youth immigrants when establishing and running a successful informal micro-business. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town.

- Kongolo, M. (2010). Job creation versus job shedding and the role of SMEs in economic development. African journal of business management, 4(11), 2288-2295.

- Lau, C.M., & Busenitz, L.W. (2001). Growth intentions of entrepreneurs in a transitional economy: The People's Republic of China. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(1), 5-20.

- Leech, N.L., Barrett, K.C., & Morgan, G.A. (2005). SPSS for intermediate statistics: Use and interpretation. Psychology Press.

- Lekhanya, L.M. (2015). Public outlook on small and medium enterprises as a strategic tool for economic growth and job creation in South Africa. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 4(4), 412 - 418

- Ligthelm, A.A., & Cant, M.C. (2002). Business success factors of SMEs in Gauteng. Pretoria: University of South Africa.

- Lin, S.F., Miao, Q., & Nie, K. (2012). A case study on entrepreneurship for sustained innovation. African Journal of Business Management, 6(2), 493-500.

- Loué, C., & Baronet, J. (2012). Toward a new entrepreneurial skills and competencies framework: a qualitative and quantitative study. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 17(4), 455-477.

- Maree, K. (2007). First steps in research. Van Schaik Publishers.

- Marshal, M.L., & Oliver, W.N. (2005). The effect of human financial and social on entrepreneurial process for entrepreneurs in India. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Purdue University.

- Mazanai, M., & Fatoki, O. (2012). Access to finance in the SME sector: A South African perspective. Asian Journal of Business Management, 4(1), 58-67.

- Melicher, L. 2009. Entrepreneurship finance. 4th Ed. London: South-Western Centage Learning.

- Monks, P.G.S. (2010). Sustainable growth of SME's. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University.

- Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2007). From human capital to social capital: A longitudinal study of technology–based academic entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 31(6), 909-935.

- Nabi, G., & Liñán, F. (2011). Graduate entrepreneurship in the developing world: intentions, education and development. Education and Training, 53(5), 325-334.

- Nahapiet, J. (2011). A social perspective: Exploring the links between human capital and social capital. The Oxford handbook of human capital, 71-95.

- Naqvi, S.W.H. (2011). Critical success and failure factors of entrepreneurial organizations: Study of SMEs in Bahawalpur. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, 1(2), 17-22.

- Noor, H.M., & Ramin, A.K. (2012). Preliminary study of rural entrepreneruship development program in Malaysia. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship.

- Nunnally, J.C. (1994). Psychometric theory 3E. Tata McGraw-hill education.

- OECD-Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2013). List of OECD member countries ratification of the convention on the OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org

- Olawale, F., & Garwe, D. (2010). Obstacles to the growth of new SMEs in South Africa: A principal component analysis approach. African Journal of Business Management, 4(5), 729-738.

- Piperopoulos, P. (2010). Ethnic minority businesses and immigrant entrepreneurship in Greece. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

- Rankhumise, E.M. (2010). Lessons and challenges faced by small business owners in running their businesses in: Proceedings of the IAMB conference, 25-27 January 2010. Las Vegas, California.

- Rogerson, C.M. (2006). Creative industries and urban tourism: South African perspectives. In Urban Forum. Springer Netherlands.

- Rwigema, H. (2004). Advanced entrepreneurship. Oxford University Press.

- Schachtebeck, C. (2018). Individual-level intrapreneurial orientation and organisational growth in small and medium enterprises (Doctoral dissertation, University of Johannesburg

- Schultz, T.W. (1970). The reckoning of education as human capital. In Education, income, and human capital .

- Serneels, P. (2008). Human capital revisited: The role of experience and education when controlling for performance and cognitive skills. Labour Economics, 15(6), 1143-1161.

- Schutte, C., Brand, R.P., & Du Preez, N.D. (2007). A business framework to network small South African enterprises for sustainability. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 18(2), 187-201.

- Sha, S. (2008). An Investigation into Problems Facing Small-to-Medium Sized Enterprises in Achieving Growth in the Eastern Cape.Shaw, E., Lam, W., & Carter, S. (2008). The role of entrepreneurial capital in building service reputation. The Service Industries Journal, 28(7), 899-917.

- Shejavali, N. (2007). SMEs in Namibia: Recommendations to address the challenges and constraints faced by small and medium enterprises in the Namibian economy. Institute for Public Policy Research, Windhoek.

- Shrader, R., & Siegel, D.S. (2007). Assessing the relationship between human capital and firm performance: Evidence from technology–based new ventures. Entrepreneurship theory and Practice, 31(6), 893-908.

- Sikalieh, D., Mokaya, S.O., & Namusonge, M. (2012). The concept of entrepreneurship; in pursuit of a universally acceptable definition. International Journal of Arts and Commerce, 1(6), 128-135.

- Smith, E.E., & Perks, S. (2006). Training interventions needed for developing black micro-entrepreneurial skills in the informal sector: A qualitative perspective. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 4(1), 17-26.

- Statistics South Africa. 2012. Quarterly labour force survey: Quarter 2. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.statssa.gov.za

- Strydom, H., & Delport, C.S.L. (2011). Sampling and pilot study in qualitative research. Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human service professions, 4, 390-396.

- Teece, D.J. (2011). Human capital, capabilities, and the firm: Literati, numerati, and entrepreneurs in the twenty-first century enterprise. The Oxford Handbook of Human Capital, OUP, Oxford.

- Tlhomola, S.J. (2010). Failure of Small Medium & Micro Enterprises in the Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Tshwane University of Technology.

- Van Vuuren, D., & Maree, A. (1999). Survey methods in market and media research. Research in Practice: Applied Methods for the Social Sciences, 269-286.

- Von Broembsen, M., Wood, E., & Herrington, M. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: South African report 2005. The UCT Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14-27.

- Von Krogh, G., & Wallin, M.W. (2011). The firm, human capital, and knowledge creation. In The Oxford handbook of human capital.

- Wasdani, K.P., & Mathew, M. (2014). Potential for opportunity recognition along the stages of entrepreneurship. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 4(1), 7.

- Weeks, R., & Benade, S. (2008). Managing a South African organisation within a dual manufacturing and services economy. Professional Accountant, 8(1), 208-218.

- Willemse, J. (2010). The forum sa. SME failure statistics. Retrieved on September 21, 2019 from https://www.theforumsa.co.za/forums/showthread.php/7808-SME-Failure-Statistics

- World Bank. (2007). Social capital. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/663341468174869302/pdf/multi-page.pdf