Research Article: 2017 Vol: 16 Issue: 1

Internal Control Systems Leading to Family Business Performance in Mexico: A Framework Analysis

Keywords

Small and Medium Enterprises, Family Businesses.

Introduction

Family businesses are those that are founded, managed and/or controlled by members of a family. These members are, usually, the majority of shareholders, top management and/or sit on the board of directors. Importantly, family businesses are called as such because at least two of the family’s generations are working together at the firm, its governance is in the hands of a family member and the family or a family member (including descendants) holds the right to at least 25% of the strategic decision making (European Commission, 2009; Family Firm Institute, 2016). Further, nonfamily members may also collaborate within the firm, although they tend to hold less strategic positions.

Without a doubt, these types of organizations, usually micro, small and medium firms, are the dominating variety among businesses (Family Firm Institute, 2016). Although, the exact number of family businesses worldwide is unclear, it has been estimated that, globally, 70% to 95% of firms are family business; furthermore, they are responsible for up to 90% of the global GDP and 80% of employment within the private sector (Family Firm Institute, 2016; EFB, 2012). Approximately half of U.S. firms are family businesses, close to 90% are in the private sector. Further in such sector, over 60% in France, 70% in Argentina, 85% in China and 93% in Italy, are family businesses (Family Firm Institute, 2016). The numbers are quite similar in Mexico; for instance, according to a study held by KPMG, over 90% of the firms listed in the country’s stock exchange are represented by a family (González, 2013) and controlled and/or owned by a family (INEGI, 2014). Therefore, family businesses are essential to the achievement of economic growth not just because of their significant amount of production (Davis, 1998), but also because of their impact on the country’s social development (INEGI, 2014).

Family businesses generally do not survive more than three generations, in fact, in many cases the transition to the third generation is quiet complex (PWC, 2014). Approximately, only 10 to 13% of family firms reach the third generation (Business Families Foundation, 2014; Family Business Institute, 2016; EFB, 2012). In some cases, this can be summed up as a firm that has been founded by the grandfather, debilitated by his children and ruined by his grandchildren (Gallo & Vilaseca, 1998), thus, resulting in the perishing of the firm by the third generation. The survival and continuity of family businesses passed the third generation is essential to the achievement of family objectives (Grabinsky, 2002), specifically, keeping the firm in the family’s hands (PWC, 2014). That said, an improved firm performance is critical to the achievement of continuity.

Internal control management is essential to the effectiveness of business’ processes and, therefore, requires the design and implementation of an internal control system (Lakis and Giriunas, 2012). There are numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between family business internal control and financial reporting (Bardhan et al., 2015; Doyle et al., 2007); however, less has been done in regards to integrated frameworks that can improve the firm’s performance. According to Deshmukh (2004), there are four main causes for family businesses to not fulfil their strategic objectives, including: human errors, cost-benefit factors, collaborators that overcome the internal control system and managers that, in order to tamper with financial reporting, override said system.

The lack of effective internal control systems is particularly problematic for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Oseifuah & Gyekye, 2013) as they tend to be more vulnerable (Saha & Mondal, 2012) and less equipped to deal with the effects. As was mentioned earlier, SMEs happen to be, in the majority of cases, family businesses (European Commission, 2009; Chrisman et al., 2005); in South Africa, approximately 80% of firms are family businesses and more than half are listed in the country’s stock exchange (Maas & Diederichs, 2007; Visser & Chiloane-Tsoka, 2014). And, in 2009, Mexico accounted for 5.1 million economic units of which 99% were MSMEs and family businesses (González, 2013). Moreover, an effective internal control system not only facilitates the firm’s performance evaluation but may also limit the degree of risk (Lakis & Giriunas, 2012). Thus, for family businesses’ organizational leaders internal control systems are important tools that make the difference between success and failure, succession or expiration.

The purpose of this study is to understand the particularities of the concepts of control and internal control, as well as develop a framework for a family business’ internal control system. Special attention was placed on the critical gaps within the existing literature and an analysis of control, internal control and internal control system was carried out to determine their specific attributes. In order to do so, four steps were taken including: (1) definitions of control and internal control were collected, sorted and classified, (2) a theoretical framework was elaborated, (3) a new internal control definition was formulated, and (4) a family business internal control system’s framework was developed to identify its design and implementation scope. This study contributes by providing insights regarding the achievement of desired performance, competitiveness and, therefore, continuity, through internal control systems. In such way as to have a positive influence on objective and goal achievement, profitability, processes efficiency, growth and competitiveness, governance, disclosure and reporting, compliance and accountability.

Review Of Literature

Control

The function of controlling is a pillar in management and is usually implemented after a strategic plan has been set in motion, that is, when corresponding objectives, strategies and tactics have been designed and executed. At such point, a series of processes and procedures are performed to monitor the efficiency and efficacy of said strategic plan. Therefore, understanding the concept of control is essential to the affectivity of the organization’s productivity and performance. As such, control may be defined and categorized according to an organization’s needs and approach (i.e., to power or authority, management, direction and system controls). Table 1 includes a brief description of various definitions and types of control. By controlling a firm’s performance, organizational leaders are able to assure that the adequate actions are taken and will be taken in the future (Drury, 2011).

| Table 1: A Brief Description Of Control Definitions Based On Four Approaches | ||||

| Online Dictionary | Power - Authority | Management | System | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merriam-Webster (2016) | To have power to make decisions | To restrict, limit or manage someone or something | To make something, such as a system or machine work | To direct the course of someone or something; supervise someone or something |

| To make someone or something act | ||||

| Business (2016) | To manage or exert control over someone or something | To act with influence on the company’s management and performance | To guide or regulate the activities of system or person | |

| Oxford Advanced American (2016) | To have power over someone or something | To limit or manage someone or something | To make a system or machine work | |

| Cambridge (2016) | To have power to decide or influence how someone will behave or something will happen | To rule or set limits on something or someone | ||

Control is a concept that has numerous definitions that vary according to industry, core business, organizational needs and managerial style, among others; thus, the lack of a universal definition leads to various interpretations of the concept (Macintosh, 1995; Lakis & Giriunas, 2012). Control may be stated in reference to internal control (i.e., governance, leadership, top management, etc.) or external control (i.e., market influence, environment, regulatory authority, etc.) (Walsh & Seward, 1990; Dhillon, 2001) mechanisms executed to ensure quality decision making and desired performance. And, it may be utilized to describe the organization’s informal and formal mechanisms used to encourage employees to fulfil strategic objectives (Long et al., 2014; Kirsch et al., 2002).

Control may also be related to the function of supervising processes and procedures’ follow-through in accordance to strategic decisions (Katkus, 1997; Buškevičiūtė, 2008). As it is a process in itself, it is triggered by the determination of a policy and/or standard and completed by their successful execution (Pickett, 2010). According to Stewart (1999) there are three basic forms of control required within an organization: control by orders (i.e., based on policies, rules and standards), control by standardization (i.e., based on strict processes and procedures) and, control by behavioural influence (i.e., based on organizational culture). Moreover, strategies related to control may include “personal centralized, bureaucratic, output, electronic surveillance, human resource and cultural management” (Child, 2005). Therefore, the concept of control is not only related to the individual, but also to the organization in that it enables the firm to monitor the effective execution of tasks and functions to monitor the achievement of effective outcomes.

The different types of control within an organization may also be viewed in accordance to the firm’s approach to control as power and/or authority, management, strategy and/or direction and system. Table 2 includes a brief description of control based on four approaches to business. Further, according to Pfister (2009) there are three main types of control, these being, strategic, management and internal control. The analysis of the concept of control, therefore, is as vast as there are definitions; however, regardless of the variations in definitions, control is an important function within any organization (Scott, 1992; Sitkin et al., 2010) to ensure affectivity, desired performance and competitiveness.

| Table 2: A Brief Description Based On Four Control Approaches To Business | |||||||

| Author(s) | Power-authority | Author(s) | Management | Author(s) | Strategy-direction | Author(s) | System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katkus (1997) | Specific processe’s monitoring and supervision | Kirsch et al. (2002) | Mechanisms to motivate individuals to achieve objectives | Scott (1992) | Mechanism to align firm’s goals with employee performance | Biciulaitis (2001) | Mean to avoid, identify and fix system disruptions |

| Bu?keviciute (2008) | Execution supervision of established decisions | Drury (2011) | Ensures the firm’s performance and future actions | Jacobs et al. (2011) | Review and monitoring of established decisions | Macintosh & Quattrone (2010) | Function to ensure system effectiveness or create desired benefit |

Internal Control

The concept of internal control also has various definitions that have come forth with the constant need to achieve competitive performance. Business context is ever-changing, thus, in order to effectively continue towards the achievement of desired performance, internal controls should be adequately designed and executed. Internal controls are or should be, as detailed as possible as to limit the margin of action (Buškevičiūtė, 2008). They are, then, utilized to properly manage and, optimally, minimize the firm’s risk and produce information for strategic decision making (Giriūnienė & Giriūnas, 2012). Therefore, they encompass a series of polices, norms, standards, means and resources (Bičiulaitis, 2001) to fulfil strategic objectives.

In 1965, Robert Anthony stated that management control is the “the process by which managers ensure that resources are obtained and used effectively and efficiently in the accomplishment of the organization’s objectives (Anthony, 1965)”. Such definition remains as top of mind because of its applicability in every organizational echelon; meaning that, such controls are significant in every task (Sitkin et al., 1994), from the mundane to the highly strategic and complex. Internal control is, then, the process by which a firm manages its objectives and monitors its outcomes and performance (King, 2011). It has also been defined as a set of instructions, processes, procedures, resources, systems and structure that ensure the achievement of strategic objectives and individual and organizational affectivity and performance (COSO, 2013; Simons, 1995); that said, although controls may be reliable and verifiable, there is no guarantee that internal controls may ensure the fulfilment of all objectives (COSO, 2013).

There are various advantages to the implementation of internal controls such as, the enhancement of capabilities, adequate information collection and analysis, employee motivation (Sitkin et al., 1994), financial reliability, achievement of standardization through compliance, (Simons, 1995) and cost reduction by preventing unnecessary losses (Basoln, 2001 & 2002). Therefore, the actual improvement of a firm’s performance is well determined by the execution of internal control policies, processes and procedures (Krishnan, 2005).

| Table 3: A Brief Chronological Set Of Definitions Of Internal Control System | |

| Author(s) | Internal control as a system |

|---|---|

| Simons (1995) | Incorporates “the formal information-based routines and procedures, which managers use to maintain or alter patterns, in organizational activities”. |

| Mackevicius (2001) | Encompasses policies, norms, rules and resources that enable the firm to effectively carry out processes and achieve its objectives. |

| Biciulaitis (2001) | Coordinates efforts to manage and minimize the business environment’s risks. |

| DiNapoli (2007) | Connects performance, plans, attitudes, politics and human resources, enabling the achievement of objectives and mission. |

| Lakis (2007) | Aligns the firm’s strategies with desired performance to ensure appropriate and effective use of resources. |

| Pfister (2009) | Enables firms to avoid, identify and correct any potential discrepancy when information processing. |

| Shim (2011) | Allows the firm to detect errors and optimally mend them, monitor performance, protect assets, achieve objectives and ensure effectiveness. |

Internal control has also been defined as a system that aids in the attainment of desired performance; Table 3 includes a brief set of definitions of internal control as a system. Viewing Internal control as a system allows firms to be proactive in regards to their decision making, that is, accurately and promptly make strategic decisions; this will, certainly, avoid any setbacks and unnecessary costs and guarantee that the system is operating effectively (Bičiulaitis, 2001; Macintosh & Quattrone, 2010). Therefore, such systems should be “understandable and economical, be related to decision centers, register variations quickly, be selective, remain flexible and point to corrective action (Hicks & Gullett, 1976).

Internal control systems, today, are much more than a mechanism to ensure financial and accounting performance, rather it is fundamental for a competitive attitude; thus, it is also significant in a firm’s corporate governance (Juheno, 1999), as, overall, having a good corporate governance makes good business sense as it has a positive influence on investments, growth and performance (Claessens, 2006), amongst others. These systems vary from organization to organization and the actual means to design and execute internal controls widely depend on the firm’s capacity and resources, as well as structure, size and core business (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2007; Doyle et al., 2007); however, they should include controls that are carefully monitored and documented and the system should incorporate cost-benefit indicators (PWC, 2007).

Internal Control in Family Business

According to Danco (1980) family businesses’ failure to grow is due to their inability or procrastination, to ensure the firm’s survival in challenging environments. However, it has been found that, in the U.S., firms headed by the founder present greater growth (Jones et al., 1988). Further, family businesses tend to be focused on the long-term (Family Business Center of Excellence, 2012) as a standard for success and will even forgo the firm’s value for survival and growth (Anderson & Reeb 2003). Therefore, the lack of family businesses’ growth is not directly related to the type of business.

It is arguable that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are less likely to design and execute internal control systems because of their limited resources, capabilities and strategic alliances, amongst other factors. However, it is not a question of SMEs being able to have internal controls, they can certainly implement them and perhaps the internal controls will tend to be informal or be less structured (COSO, 2013) than those found in larger organizations. Internal control should be closely aligned with the firm’s mission and vision statements, values and the very people that work within the firm because these are all correlated. This notion ultimately aids family business firms in the effective definition, design and execution of internal controls because it responds to their natural sense of family and business.

Family businesses have a special characteristic that comes natural when a family creates a business, this is, familiness, also known as “the bundle of resources that are distinctive to a firm as a result of family involvement” (Habbershon & Williams, 1999). Thus, arguably, the greatest advantage lays in their convergence of business and family systems. It is no surprise that family businesses are “family oriented” and, as such, they transmit their values, sense of trust, personal encouragement and even control, from the family to the firm. Such nature is well associated with their influence of trust and control on firm performance (Baines & Wheelock, 1998), in fact, familiness is positively and directly associated with Mexican family firm’s performance (Baños Monroy et al., 2015). Hence:

P1: Family business’ familiness strengthens the firm’s internal control system and impacts performance.

When the business environment is presented with regulatory authorities that demand compliance and/or higher risks due to uncertainty, family businesses are more inclined to take on internal controls; in a sense, they are “forced” to rely on their resources and capabilities to ensure the firm’s prosperity (Carney et al., 2009; Klapper & Love, 2004). As uncertainty reduces, these firms have more opportunities for external resources and are more inclined to welcome nonfamily members (La Porta et al., 1998; Walsh & Seward, 1990). The latter does not mean that the need for internal controls reduces, rather, that they are not vital to survival as the increase in resources and capabilities aids in this issue.

Family businesses have several advantages; they have their own culture shared amongst family members and transmitted from the family system to the business system. They have a long-term mission and vision which is transmitted to their objectives, strategies and tactics and their managerial style is less bureaucratic with greater autonomy and speed in decision making, which provides for greater targeted marketing (Rivas, 2014). Further, they have a more personalized relationship with internal and external stakeholders (Fielder, 1999), which generates long-term relationships reflected in brand loyalty. Hence:

P2: The implementation of an internal control system in family businesses influences the firm’s strategic plan.

Internal control systems may incorporate any and all indicators that managers deem necessary to ensure goal achievement, performance and competitiveness. For instance, to reduce errors (Wallace & Kreutzfeldt, 1991), avoid discrepancies and even detect criminal intent (Nestor, 2004) and fraud (Marden & Edwards, 2005; Belloli, 2006). These would seem like large firm problems, however, these are issues that continuously arise in SMEs and family businesses, regardless of their size, in many cases because there is excessive trust in employees and no internal controls. That said, by implementing such internal controls, among other factors, family business managers are equipped with the tools to steer employee’s behaviours and add value (Carey et al., 2000; Carcello et al., 2005) to the firm.

The development of indicators is essential to the process of controlling and monitoring execution of any task, function and procedure, etcetera. The design of any indicator should be based on the firm’s core objectives, mission and vision. For such matter, it is important to know what the firm/division/department/team/employee needs to do (i.e., performance indicators), how did the firm/division/department/team/employee perform (i.e., key result indicators-KRIs) and what does the firm/division/department/team/employee need to do to significantly impact the overall performance (i.e., key performance indicators-KPIs) (Parmenter, 2007). Answering such questions leads to strategic, financial and operational effectiveness which, in turn, is reflected in the firm’s performance. Hence:

P3: The implementation of an internal control system in family businesses influences the firm’s indicators.

P4: The implementation of an internal control system in family businesses influences the firm’s strategic planning process.

P5: The implementation of an internal control system in family businesses impacts organizational performance and competitiveness.

Framework and Discussion

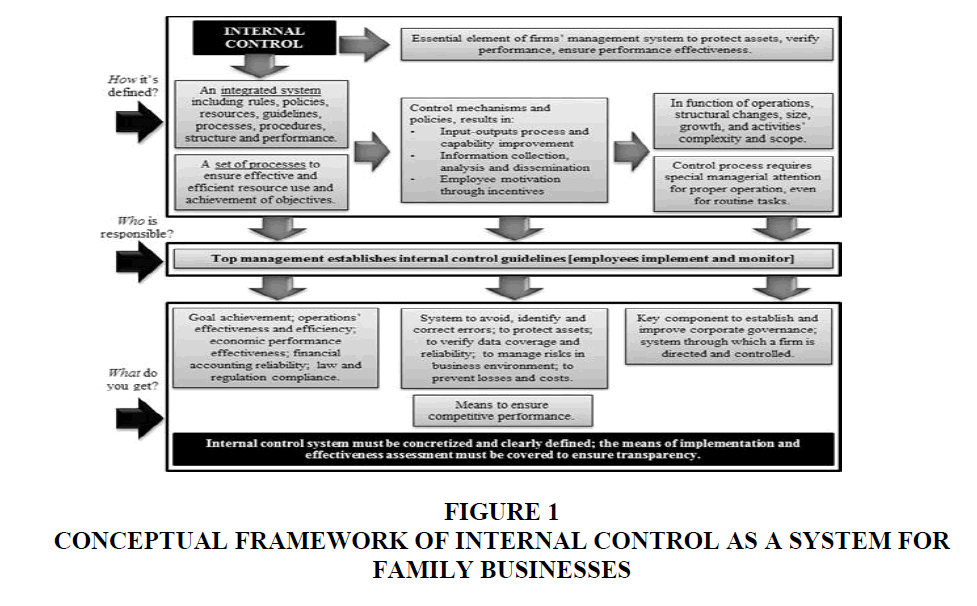

Effective internal control is essential to all firms, regardless of their category or size; therefore, family businesses are equally capable of designing and executing effective internal controls. In fact, it is a matter of how, who and what: How is internal control defined (i.e., the firm’s definition)? Who is responsible (i.e., all internal stakeholders involved in the development, execution and monitoring of internal controls)? And, what do you get (i.e., outcomes, benefits, of internal controls)? Figure 1 depicts a conceptual framework of internal control as a system for family businesses derived from the concepts of control, internal control and internal control system examined.

A thorough analysis of internal control systems may help family business managers understand their importance and also delegate efforts towards their design and execution. Therefore, it is important that family businesses ask how they are defining internal control within their system. The next step is determining the internal stakeholders that will be fulfilling the tasks and functions related to the design, execution and monitoring of the internal control system; that is, who will be delegated the responsibility of ensuring the effective outcome of the system. Finally, family businesses should be well aware of the direction they are heading in, the alignment of their vision and mission with the results of their internal control system; meaning, what benefits the firms will be obtaining by implementing and monitoring said system. These three simple questions will enable family businesses to effectively decrease disruptions, unnecessary costs and enhance performance and competitiveness.

The above examination of the concepts of control, internal control and internal control system, derived from previous literature, provided for the development of the conceptualization of internal control system; it is considered that the definition may aid small and medium family business to appreciate the attributes of controls within the organization; accordingly.

Internal control systems (ICS) are central to firms’ management systems and designed as per its mission and vision. ICS’ purpose is to protect assets, verify financial and operational performance, avoid, identify and rectify errors, prevent risks and unnecessary costs due to losses and guarantee goal accomplishment and competitive performance.

Family Businesses in Mexico

Family businesses are the vast majority in Mexico, in fact, an approximate of 95% of the firms are family owned (The Economist, 2004). It is true that a significant number of these firms are mom & pop shops and SMEs, however, many, just as around the world, are large and multinational organizations (Kachaner et al., 2012; Espinoza Aguiló & Espinoza Aguiló, 2012). Mexican families share very strong bonds that do not dissipate over time or when they take on a business. For the most part the notion is that “la sangre es la sangre”, blood is blood, meaning that, blood comes before all else. These bonds translate into a special kind of relationship or familiness as referred to in business. Familiness refers to the family’s influence in the family business (Pearson, et al., 2008). It facilitates the understanding and agreement of the convergence of managerial and family goals and objectives (Durán-Encalada et al., 2012), such as, financial and nonfinancial, strategic and operational objectives.

Family businesses perform better than nonfamily firms when unpredictable circumstances arise, that is, they are resilient and are “proficient” in withstanding shifts in the business environment (Aminoff, 2012). In such sense, these firms can present risk aversion and total resistance to change and also be willing to take on risk (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007), which largely depends on ownership, managerial style and existence and efficiency of internal controls. In many cases in Mexico, family firms survive a while longer because they endure the hard times with a winning attitude and posture; unfortunately, it remains that their lack of internal controls sooner or later impact the firm’s effectiveness.

Some issues with family businesses are the constant potential for conflict (Lee & Rogoff, 1996) caused by rivalry (Levinson, 1971) and prioritization of personal gain (i.e., the family’s gain) over the firm’s value (Shleifer & Vishny 1997), conflict of interests (i.e., those of family members and those of the firm), in some cases unprepared and/or unwilling next of kin and less access to external resources, causing grater need for self-financing (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). These issues transcend cultural barriers, as they arise in family businesses in Mexico as well. Besides the fact that there is conflict in the firm, the very presence of these issues are clear signs that internal controls are required to effectively manages the firm.

There are several firms that began operations with the family concentrated in ownership and management (Chandler, 1990) and, today, strategic positions are still traditionally occupied by family members; however, these firms have evolved towards the inclusion of nonfamily members. That is, exclusivity has decreased as they seek a more professionalized managerial structure, style and team (Thacker, 2012). Those lacking in the achievement of professionalization will most likely find it difficult, if not impossible, to procure the desired performance, sustained growth and internationalization (Fernández & Nieto, 2005). Thus, it comes to no surprise that so many family SMEs in Mexico perish after so little time in the market.

One of the major issues of corporate governance in Mexican firms is the lack of regulation and transparency of disclosure compliance (Husted & Serrano, 2002). Most family businesses in Mexico make serious efforts for the firm to remain “in family hands”, especially SMEs; however, larger family firms and/or those seeking internationalization, are less rigid on this point and have opened their doors to nonfamily members for strategic positions. That said, in Mexico, corporate governance is left in hands of the director/CEO/founder and the appointment of a board member is in the hands of the family (La Porta et al., 1999). Furthermore, members of boards of directors monitor shareholder control by means of both business and family relations and enforce control by means of contracts (Espinoza Aguiló & Espinoza Aguiló, 2012); therefore, corporate governance remains an issue in the country. Mexican family firms, therefore, will need to delegate efforts towards improving or in many cases establishing, their corporate governance (Husted & Serrano, 2002), as well as strategically design and execute internal control systems to achieve a competitive posture.

A significant issue with family business firms is that they place less attention to their performance and are more focused on the challenge of survival (Kachaner et al., 2012). In doing so, their overall performance decreases. Claessens, Djankov & Lang (2000) have stated that unsatisfactory performance in family businesses is often due to the prioritization of the family’s wealth over other stakeholders. In such case, any decrease in performance requires the design of internal controls that may guide the firm towards improvement. Mexican family businesses lack internal controls because, 1) they do not understand the concept or are unaware of them, 2) they consider them to be an unnecessary cost and, 3) implementing such controls implies making big changes.

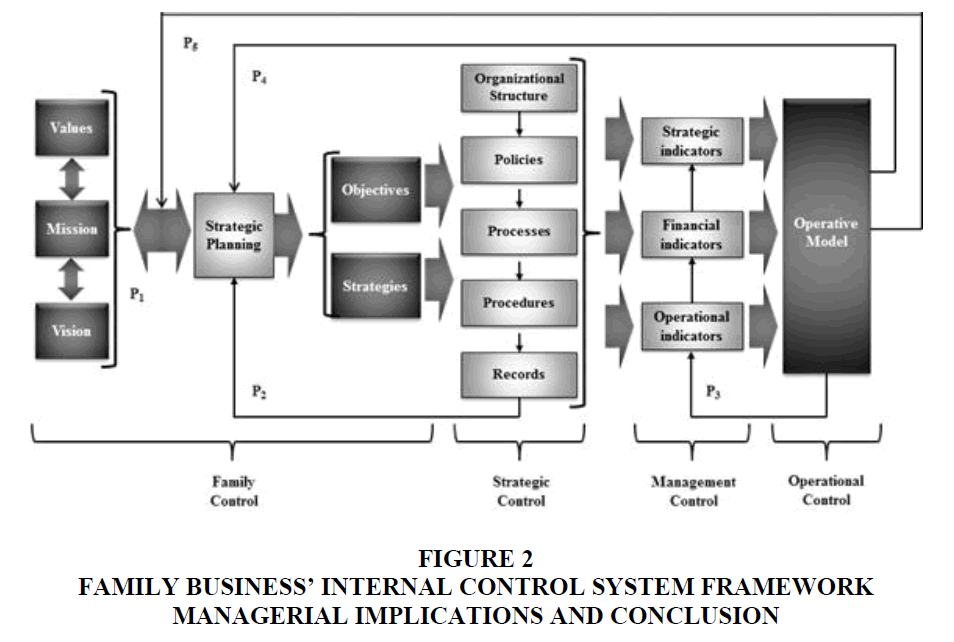

Family businesses in Mexico, as in many emerging markets, may well be benefited by the adequate and prompt design and implementation of an internal control system. Figure 2 depicts an internal control system framework for family business firms. The system was originally developed with the intention of portraying the current situation (i.e., areas of opportunity) and providing a system for family businesses operating in Mexico, however, it has been considered that the framework is also suitable for most any emerging market. Such system should facilitate the planning, organization and control of the firm’s operations (i.e., strategic, financial and operational planning, organization and control).

The framework describes the way four levels of control (i.e., family control, strategic control, management control and operational control) interact within an internal control system. Family control is the first control because it is stems from and is communicated by the family. The attributes of this control are transmitted from strategic positions within the firm (i.e., mostly family members). It is visible in the firm’s strategic long-term plan based on its familiness and is the basis of the organization’s strategies and objectives. The second control is strategic control, which resides in the firm’s tactical positions. It is visible in the firm’s goals, objectives and strategies and is the basis of the organization’s structure, policies, processes and procedures and records. At this point, objectives’ achievement and strategies’ execution are vigilantly monitored in order to detect and mend any areas of opportunity, discrepancies and mistakes, etcetera.

Management control is placed in the third position as it is a critical control. Those responsible for the implementation of said control are employees in the firm’s managerial and/or tactical positions; occasionally, some nonfamily members occupy such positions due to the considerable trust the family has in them. This control is visible in the firm’s strategic, financial and operative indicators, of quality, productivity, performance, efficiency, efficacy, etc. based on the firm’s strategic plan; furthermore, it is the basis of the firm’s operative model.

Finally, the operational control is assessed by the firm’s operational positions, in which most nonfamily members are located. It is visible in the firm’s strategic objective achievement, as well as performance and competitiveness. As such, its design ensures consistency in routine and extraordinary tasks. The outcome of every process within the system generates feedback to maintain the system’s quality. And, in case of deficiencies, corrective actions (i.e., training, motivation, leadership, discipline or termination) may be taken. Thus, it is the basis for the effective monitoring of the firm’s strategic plan and internal control system.

There are numerous definitions of the concepts of control and internal control, which leads to, at least, the same amount of analysis and perceptions. Such variations are due to different visions of what internal mechanisms should be, how they should operate, what should the outcome be and their impact on the firm’s overall standard of success, meaning, productivity, performance and competitiveness. Consequently, a particular concept of internal control system was developed by examining the concepts of control, internal control and internal control system; this was based on four approaches to business, that is: power-authority, management, strategy-direction and system. Such definition assisted in the creation of a framework of an internal control system for family businesses.

Effective internal control systems are essential to family businesses’ outcomes; additionally, the managers, who are in general responsible for internal control upkeep, not only need to understand the importance and influence of the system on their performance, but also need to effectively implement it. For such matter, the firm’s values, mission and vision, objectives and strategies, structure, policies, processes and procedures, should be arranged in line with the selected performance indicators.

Family SMEs in Mexico are very similar to those around the world. The advantages, disadvantages, problems, risks, among others, are, for the most part, the same. In Mexico, it is the familiness that sustains a family firm for a longer period of time (not necessarily beyond a second generation) and it is the utter lack of internal controls that ultimately destroys the firm. Of course, in many cases, Mexican family SMEs do not have an internal control system because the founder, owner and/or top manager(s), are unaware of its importance, are not familiar with the concept and, in general, lack know-how. For such reason, it was considered important to develop a framework that would facilitate family businesses in the fulfilment of their objectives, achievement of their desired performance and, therefore, competitiveness. There are clear advantages which range from the enabling of transparent compliance and disclosure, efficiency of resources and capabilities, discrepancy detection and avoidance, to optimal strategic decision making and sustained growth; nonetheless, in Mexico, like in many emerging markets, family business’ success well depends on the firm’s resilience and ability to respond in a changing and uncertain environment.

Future Research

Future research might study the effects of system mishaps on family firms’ performance; that is, the impact of the frequency, relation of type of task (routine or extraordinary), the performance indicators and levels of control. Further, future research could also evaluate the framework within family business firms in emerging markets to determine the specific effects on optimization, governance and strategic decision making.

References

- Aminoff, P. (2012). Built to last family businesses lead the way to sustainable growth. Building a Robust Business.

- Anderson, R. & Reeb, D. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301-1328.

- Anthony, R.N. (1965). Planning and control systems: A framework for analysis. Graduate School of Business Administration.

- Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D.W. & Kinney, W.R. (2007). The discovery and reporting of internal control deficiencies prior to sox-mandated audits. Journal of Accounting and Economic, 44(1), 166-192.

- Baines, S. & Wheelock, J. (1998). Working for each other: Gender, the household and microbusiness survival and growth. International Small Business Journal, 17(1), 16-35.

- Ba�os Monroy, V.I., Ram�rez Sol�s, E.R. & Rodr�guez-Aceves, L. (2015). Familiness and its relationship with performance in Mexican family firms. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 14(2), 1-22.

- Bardhan, I., Lin, S. & Wu, S.L. (2015). The quality of internal control over financial reporting in family firms. Accounting Horizons, 29(1), 41-60.

- Basoln, T. (2001). Internal control. Journal of Management and Training, 1.

- Belloli, P. (2006). Fraudulent overtime. International Auditor, 63(3), 91-95.

- Biciulaitis, R. (2001). Organization of the internal control system and its role in increasing the efficiency of management. Business Dictionary.

- Bu?keviciute, E. (2008). Public finances. Cambridge Dictionary Online.

- Carcello, J.V., Hermanson, D.R. & Raghunandan, K. (2005). Factors associated with U.S. public companies investment in internal auditing. Accounting Horizons, 19(2), 69-84.

- Carey, P., Simnett, R. & Tanewski, G. (2000). Voluntary demand for internal and external auditing by family businesses. A Journal of Practice and Theory, 19(1), 37-51.

- Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E. & Yang, X. (2009). Varieties of Asian capitalism: Toward an institutional theory of Asian enterprise. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(3), 361-380.

- Chandler, A. (1990). Scale and scope. MA: Harvard University Press.

- Child, J. (2005). Organization: Contemporary principles and practice. MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Chrisman, J.J., Chua, J.H. & Sharma, P. (2005). Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 555-575.

- Claessens, S. (2006). Corporate governance and development. World Bank Research Observer, 21(1), 91-122.

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S. & Lang, L. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(2), 81-112.

- COSO. (2013). Internal control. Integrated framework.

- Danco, L.A. (1980). Inside the family business. Cleveland: The University Press.

- Davis, J.A. (1998). Families in business. Harvard Business School Global Alumni Conference, 16-19.

- Deshmukh, A. (2004). A conceptual framework for online internal controls. Journal of Information Technology Management, 15(4), 23-32.

- Dhillon, G. (2001). Violation of safeguards by trusted personnel and understanding related information security concerns. Computers & Security, 20(2), 165-172.

- DiNapoli, T.P. (2007). Standards for internal control in New York state government.

- Doyle, J.T., Ge, W. & McVay, S. (2007). Accruals quality and internal control over financial reporting. The Accounting Review, 82(5), 1141-1170.

- Drury, C. (2011). Cost and management accounting. Mexico: CENGAGE Learning.

- Dur�n-Encalada, J.A., Mart�n-Reyna, J.M. & Montiel-Campos, H. (2012). A research proposal to examine entrepreneurship in family business. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 8(3), 58-77.

- EFB. (2012). European family business.

- Espinoza Aguil�, T.I. & Espinoza Aguil�, N.F. (2012). Family business performance: evidence from Mexico. Cuaderno de Administraci�n, 25(44), 39-61.

- European Commission. (2009). Overview of family?business?relevant issues: Research, networks, policy measures and existing studies. Final Report of the Expert Group, 1-33.

- Family Business Center of Excellence. (2012). Built to last family businesses lead the way to sustainable growth.

- Family Business Institute. (2016). Succession planning.

- Family Firm Institute. (2016). Global data points.

- Fern�ndez, Z. & Nieto, M.J. (2005). Internationalization strategy of small and medium-sized family businesses: Some influential factors. Family Business Review, 18(1), 77-89.

- Fielder, E. (1999). Corporate family matters. Business forms, Labels & Systems, 37(13), 8.

- Gallo, M. & Vilaseca, A. (1998). A financial perspective on structure, conduct and performance in the family firms: An empirical study. Family Business Review, 11(1), 35-47.

- Giriuniene, G. & Giriunas, L. (2012). Assessment of internal control system in Lithuania. Economics and Management, 17(4), 1240-1244.

- G�mez-Mej�a, L.R., Tak�cs Haynes, K., N��ez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socio-emotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106-137.

- Gonz�lez, J. (2013). Empresas familiares En M�xico: El Desaf�o De Crecer. Madurar Y Permanecer.

- Grabinsky, S. (2002). Din�mica Y Conflictos En Las Empresas Familiares. Mexico: Del Verbo Emprender S.A. de C.V.

- Greenhaus, J.H. & Beutell, N.J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76-88.

- Habbershon, T.G. & Williams, M.L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1-25.

- Hicks, H.G. & Gullett, C.R. (1976). The management of organizations.

- Husted, B. W. & Serrano, C. (2002). Corporate governance in Mexico. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(3), 337-348.

- INEGI. (2014). Resultados Definitivos.

- Jacobs, F.R., Berry, W.L., Whybark, D.C. & Vollmann, T.E. (2011). Manufacturing planning and control for supply chain management. McGraw-Hill.

- Jones, S., Cohen, M.B. & Coppola, V.V. (1988). The Coopers & Lybrand Guide to Growing Your Business. NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Juheno, W.F. (1999). Financial systems and development in Africa. World Bank EDI Seminor.

- Kachaner, N., Stalk G. & Bloch, A. (2012). What you can learn from family business.

- Katkus, A. (1997). State economic control. Vilnius: Mintis.

- King, A.M. (2011). Internal control of fixed assets: A controller and auditor?s guide. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Kirsch, L.J., Sambamurthy, V., Ko, D.G. & Purvis, R.L. (2002). Controlling information systems development projects: The view from the client. Management Science, 48(4), 484-498.

- Klapper, L.F. & Love, I. (2004). Corporate governance, investor protection and performance in emerging markets. Journal of Corporate Finance, 10(5), 703-728.

- Krishnan, J. (2005). Audit committee quality and internal control: An empirical analysis. The Accounting Review, 80(2), 649-675.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F. & Schielfer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. The Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471-517.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113-1155.

- Lakis, V. (2007). The court system: Development and problems monograph. Vilnius, Lithuania: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla.

- Lakis, V. & Giriunas, L. (2012). The concept of internal control system: Theoretical aspect. Ekonomika, 91(2), 142-152.

- Lee, M.S. & Rogoff, E.G. (1996). An investigation of differences in goals, attitudes and family/business conflict. Family Business Review, 9(4), 423-437.

- Levinson, H. (1971). Conflicts that plague family businesses.

- Long, C.P., Sitkin, S.B. & Cardinal, L.B. (2014). Managerial action to promote control, trust and fairness in organizations: The effect of conflict. In J.A. Miles, New Directions in Management and Organization Theory, 413-446.

- Maas, G. & Diederichs, A. (2007). Manage family in your family business. North cliff: Frontrunner.

- Macintosh, N. (1995). Management accounting and control systems: A behavioural approach. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Macintosh, N.B. & Quattrone, P. (2010). Management accounting and control systems: An organizational and sociological approach. UK: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Mackevicius, J. (2001). Audit: Theory, practice, prospects. Lithuania: Lietuvos Mokslo Centras.

- Marciariello, J. (1984). Management control systems. NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Marden, R. & Edwards, R. (2005). Employee fraud in the casino and gaming industry. International Auditing, 20(1), 21-30.

- Merriam-Webster. (2016). Control.

- Nestor, S. (2004). The impact of changing corporate governance norms on economic crime. Journal of Financial Crime, 11(4), 347-352.

- Oseifuah, E.K. & Gyekye, A.B. (2013). Internal control in small and microenterprises in the Vhembe district. European Scientific Journal, (9), 241-251.

- Oxford Advanced American Dictionary. (2016). Control.

- Parmenter, D. (2007). Developing, implementing and using winning KPIs. NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Pearson, A.W., Carr, J.C. & Shaw, J.C. (2008). Toward a theory of familiness: A social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(6), 949-969.

- Pfister, A.J. (2009). Managing organizational culture for effective internal control: From practice to theory. Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer Physica-Verlag.

- Pickett, K.H. (2010). The Internal Auditing Handbook. London: CPI Antony Rowe.

- PWC. (2007). The internal control system: A rapidly changing management instrument.

- PWC. (2014). Up close and professional: The family factor global family business survey.

- Rivas, M.R. (2014). Las 10 Ventajas Competitivas De Las Pymes Familiares. Negocios.

- Saha, A.K. & Mondal, K.C. (2012). Internal control policy in the RMG sector of Bangladesh. Asian Business Review, 1(1), 67-71.

- Scott, R. (1992). Organizations: Rational, natural and open systems. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Shim, J.K. (2011). Internal control and fraud detection. Global Professional Publishing Ltd.

- Shleifer, A. & Vishny, R.W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737-783.

- Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control: How managers use innovative control systems to drive strategic renewal. MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Sitkin, S.B., Cardinal, L.B. & Bijlsma-Frankema, K.M. (2010). Organizational control. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Sitkin, S.B., Sutcliffe, K.M. & Schroeder, R.G. (1994). Distinguishing control from learning in total quality management: A contingency perspective. Academy of Management Review, 19(3), 537-564.

- Stewart, R. (1999). The reality of management. UK: Butterworth Heinemann.

- Thacker, S.C. (2012). Big business, democracy and the politics of competition. The Oxford Handbook of Mexican Politics.

- The Economist. (2004). The family business model not only survives in Mexico. Still Keeping It in the Family.

- Visser, T. & Chiloane-Tsoka, E. (2014). An exploration into family business and SMEs in South Africa. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 12(4), 427-432.

- Wallace, W.A. & Kreutzfeldt, R.W. (1991). Distinctive characteristics of entities with an internal audit department and the association of the quality of such departments with errors. Contemporary Accounting Research, 7(2), 485-512.

- Walsh, J.P. & Seward, J.K. (1990). On the efficiency of internal and external corporate control mechanism. The Academy of Management Review, 15(3), 421-458.