Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 2

Intercultural Issues in International Tourism Negotiations

Dorsaf Dellech, IHEC Carthage

Abstract

This research showed that the conduct and success of international trade negotiations are directly affected by intercultural variables. Our aim then is twofold. First, we try to identify the attributes of international negotiation by tourism and hotel managers. Second, we explore these managers’ sensitivity to consider the intercultural factor in negotiations with stakeholders in their target markets. Our results show that negotiators, despite their ongoing involvement in international negotiations, fail to fully understand the importance of intercultural attributes in the current context of a globalized economy.

Keywords

Negotiation, Intercultural, Culture and Tourism.

Introduction

All companies implement a set of exchange and communication practices and dynamics that are not culturally neutral, because

"The silent language of culture colors all human actions to some degree or another" (Faure et al., 2000).

Culture determines the functioning of the organization. It therefore has a measurable effect on its structure, strategic orientations and the attitudes and behavior of its stakeholders. In the field of tourism, the intercultural problem takes on its full meaning. Then, it would not be to think that globalization leads to a standardization of cultures. When it comes to doing business across borders - from the first contact to the effective implementation of a partnership - everything is "culture". Integrating the intercultural dimension into one's internationalization strategy is not only common sense to respect others in order to promote an exchange, but also to avoid misunderstandings, pitfalls and errors of judgment: a valuable saving of time and money.

Theory-wise, for the human sciences in particular, the literature on culture as a "system of values and beliefs" is remarkably abundant. On the other hand, in the managerial context, the cultural perspective must be approached differently. Indeed, the final goal of such a trend of research is not to take on culture as such, nor its status, but to study some corporate modes and practices and the different cultural factors that can affect them. Of the authors who have tried to integrate culture as a relevant variable in their organizational research, we can mention Adler (1986), Bond (1986), Hall & Hall (1990), Hofstede (1991), Saidi & Debabi (2016) and Dellech & Debabi (2017). Admittedly, their studies, thus oriented towards a revaluation of the cultural variable, which had long been rejected and considered as a "residual variable" in the organization's contingent theories, not only reinforced the tendency towards interdisciplinary complementarity, but also a gradual transformation in the very attitude of management.

Nevertheless, some glaring limitations (theoretical, conceptual and methodological) are still persist, proving that culturally-based managerial theoretical approaches are scientifically frail. However, we are beginning to witness a conceptual and methodological evolution in cultural research. Such an evolution is manifested in particular in the transition from normative to relative and descriptive conceptions, the enhancement of the role of the individual in the cultural context, the distinction between the cultural system and the social system and the enhancement of the "cultural unconscious". Thus, if we consider a line of research conducted on the effect of culture on company strategies, specifically international sales strategies, we notice that international trade negotiations are directly affected by cultural factors in contexts involving people from different cultural backgrounds. Despite this, it has not aroused the specific interest of researchers in this very important organizational component, namely intercultural negotiation. Indeed, research in this field is "limited" as

"It puts negotiation processes at the forefront and highlights other issues in the background (such as cultural differences between negotiators, the formal or informal nature of negotiation, the importance of the means of communication as a medium of exchange, etc.) even if they remain otherwise fundamental" (Faure et al., 2000).

Despite this theoretical and thematic deficiency, some researchers, aware of the importance of this approach, have insufficiently tried to explain the multiple impacts of culture on international trade negotiations. Exporters, business men, managers of exporting companies and tourism service providers negotiate almost daily with their respective partners and customers from different cultures. The intercultural is therefore always at the heart of their negotiations. One of the areas where intercultural negotiation is omnipresent is tourism and hotels. Intercultural encounter is the cornerstone of the tourism relationship. We cannot ignore the fact that tourism officials, sales representatives and decision-makers have to manage international meetings on a regular basis and that their respective affairs require negotiations whose process is difficult to conduct if we do not understand cultural influences, since the parties often apply negotiation strategies related to their respective cultures (Khakhar & Rammel, 2013).

Indeed, in order to successfully conclude their negotiations at the international level, it is essential for them to have "cultural references and orientations". The development of tourism on a global scale is now giving rise to a system of collaboration between groups, partners, correspondents, hotel chains, etc. based on multiculturality. The presence of a diversified clientele in the hotel sector, for example, combined with high employee mobility, has resulted in the emergence of multicultural teams. Management-wise, this calls for a closer collaboration between employees of different beliefs, values and attitudes (Leroux & Pupion, 2014).

Research on interculturality is extensive and covered all aspects of human activities. However, an interest in international trade negotiations and the interaction of its variables with interculturality, particularly in a managerial context such as tourism and hotel business, remains a path that attracts too few researchers in this field. Our research question therefore is whether tourism stakeholders are aware of the main attributes of intercultural negotiation and to what extent are they able to identify and decipher the cultural imperatives of their foreign target market in order to succeed in their negotiations?

Our paper is organized as follows. The first section reviews the literature on the concept of interculturality by highlighting its influence on the conduct of international negotiations. The second section reports on an empirical study that allowed us to check the degree of knowledge of the attributes of negotiation by tourism and hotel industry actors and their ability to take this knowledge into account in their international negotiations.

Interculturality and International Negotiation

Having emerged a few years ago, "intercultural" still raises multiple questions, because at one point this term was belittled and used in heterogeneous ways. Thus, it was common to use, for example, intercultural instead of cultural to refer to any activity in which the cultural variable is involved, or to replace and recycle the term "international".

Diversity in Defining Interculturality

Before presenting the definitions of "intercultural", we will try to plot some examples which show that this term has been used in different ways, from the most indeterminate to the most accurate (Camilleri, 1995):

1. Indifferent to the prefix "inter", some apply it to all contexts where the cultural variable is involved: cultural for intercultural.

2. This term is used for contexts where there are at least two different cultures.

3. The term is also used in the study of communication barriers in order to indirectly improve exchanges between the systems and involved partners. Thus, the prefix "inter" begins to be taken into account.

4. It is a project that tends to deliberately manage the relationship between culturally different groups or individuals in such a way as to avoid at least the dysfunction of their cohabitation.

5. Grouping these definitions together, we will try to show that interculturality has a specific and a distinct meaning. Indeed, and as we have already pointed out, it is interdisciplinarity in the humanities and social sciences that initially inspired intercultural research. This interdisciplinarity has developed a very relevant logic, which paved the way for the reinterpretation of intercultural relationships.

Under this line of research, the main premise assumes that

"Once socialized in one culture, the human being has the ability to appropriate the system of norms of another culture and to behave appropriately when the cultural norms of the system are different" (Niklas, 1995).

Consequently, interculturality is understood as

"The set of interactions and interrelationships, with the status of negotiated equality, that occur between groups or between individuals with different cultural systems in order to transform and overcome belonging in order to create new identities. From an interactionist point of view, we can speak of intercultural when subjects with different cultural systems interact effectively" (Henriquez, 2000).

The above definitions to interculturality therefore clearly refer to diversity, complex problems and the resulting greyish solutions. In short, it is a set of behaviors, attitudes, methods of analysis and understanding of problems arising from pluralistic contexts. Interculturality, as defined in this way, is the explanation of differences in meaning and behavior resulting from diverse cultural systems. In fact, our reasoning rests essentially on the assumption that a system of cultural norms lends itself to its coherent nature. However, in modern societies this principle is not always checked. Indeed,

"These societies reveal considerable cultural differences between various sectors and social planes, horizontal differences (between regions of a country's North and South), and vertical differences (differences between sub-cultures). These differences may be greater than those between cultures" (Nicklas, 1995).

This last assumption therefore leads us to question the essence of the intercultural problem, regardless of the context in which it is understood (regional, national, international, etc.). Indeed, and bearing on the above, it is clear that this problem does not lie in the observation of cultural differences, but rather in the institution of these differences insofar as these supposed differences support representations that individuals use idiosyncratically as a support to project their limited vision of other cultures.

This latter idea is in line with Lenclud's (1991) position that the problem lies not in differences, but in the countless ways in which people here and elsewhere institute differences as objects of thought and as a pretext for action. In intercultural contexts, cultural differences as studied and specified by researchers do not tell us about the dynamics of intercultural interaction. They are specific, both for its actors and in its particular context, as well as specific in the behavior that manifests itself as a result. Cultural differences only provide us with limited information about the structure of interactions. It is clear that such obstacles explain the fact that the intercultural approach has been unproductive in analyzing the impact of cultural variables on the different aspects of corporate life, particularly in terms of its relationship with its market.

In general, the literature is reluctant to address the concept of interculturality in management and marketing, as it is difficult to manipulate and as it is often taken in tautological or caricatural terms. Despite these difficulties, the inevitability of the intercultural problem during international negotiations now requires a reflective and then a scientific treatment: the notions of the intercultural perspective are gradually being refined and represent very important future challenges.

The Influence of Interculturality on the Conduct of Negotiations

Intercultural negotiation is an interaction, i.e. the alignment of two perspectives expressed through a strategic and a tactical approach. This approach is implemented under a system of legal, organizational, institutional and cultural constraints (Faure, 1999). Intercultural negotiations are complex and uncertain, follow a long and "non-linear" process and are generally conducted by teams with multiple and complementary skills (lawyers, economists, financiers, sales representatives, etc.). Context and situation are very important in intercultural negotiations. These become much more complicated when cultural differences are added to them (Lavissière, 2017).

In the managerial context, integrating interculturality into the concerns of management researchers is all the more justified since economic exchanges no longer take place within the limited framework of local markets; they take place now in broader and wider contexts (regional, international, etc.). Thus, for multinational companies, some researchers believe that in a different culture than their own, economic actors find themselves powerless. There is the language factor, but there are also social values, customs, time, space, non-verbal communication, cognitive and affective integration modes, etc. In an increasingly global economy, negotiation is a unique trade prelude, which tends to be more and more international, recasting its multipolar nature (Dupont, 2003). Several companies that regularly negotiate abroad use international negotiation specialists. These third parties may be consultants, traders, businessmen, etc. (Reynolds et al., 2003).

In reality, the impact of cultural differences can be identified in a negotiation at several levels. Referring to Debabi's (1997) work, we can retain the following four axes: The negotiation situation (time, space, etc.), its conduct (slowness, rigidity, patience, rhythm, flexibility, etc.), its process (multiplication of sequences, variation of stakes according to the phases pursued, retroactive movements, etc.) and its results (sincere or flouted compromises, accepted oral contract, mutual agreement translated into a written contract, etc.).

From all the above, it is clear that the study of intercultural negotiation is not an easy task, partly because this issue has always been approached in an indirect way, and partly because of the complexity of the issues and challenges involved in negotiations. Indeed, this is where all the complexity lies, but also the validity of the research perspective taken. Although most researchers and professionals defend the view that interculturality is an important factor in international negotiations, they are unanimous in admitting that there is still no consensus on the to-be-used research methods and that the taken approaches remain competitive and different with a wide variety of paradigms. Indeed, opinions and views range from a minority of skeptics to a majority of defenders.

In his work on interculturality and negotiation, Dupont (1994) provided a fairly in-depth analysis of the divergence between these two positions. From this analysis, we learn that skeptics assume that the effect of culture on the negotiation process is a peripheral effect and that it has too often been overestimated by researchers. Culture affects the negotiation process but its influence is less important than other factors that Zartman (2004) describes as central, such as the division of resources, exchanges, power, etc.

The two main arguments put forward by the sceptics to question the explanatory power of culture on negotiation are:

1. The ambiguity and imprecision of culture as a concept. Indeed, the number and complexity of the dimensions of culture make it an inadequate concept to explain the conduct and outcome of the negotiation.

2. Adequacy of negotiation to the analysis. The main interest in analyzing negotiation is to find ways and methods to improve its process and reach better results. The focus on the negative effects must be reconsidered, and researchers' efforts must be directed towards understanding the reasons for success. This is something that has not yet been claimed by the proponents.

As for the defenders, they are positively united around the effect of culture on international trade negotiations. However, their opinions and points of view tend to diverge, allowing Dupont (2003) to classify them into two subgroups, pure partisans and moderate or pragmatic partisans. Pure supporters strongly support the impact of culture on international negotiations. Indeed, they recognize that culture is an integral part of international negotiations. Moderate supporters agree that culture has a major influence on negotiations, but they believe that it is within certain limits and under certain pre-established conditions.

Cultural Variables and Negotiator Behavior

Culture is an invisible variable (Brett & Gelfand, 2004) and through its external manifestations, it affects the different dimensions of negotiation (Faure, 2004). Understanding how culture influences negotiation not only helps the negotiator to conclude the deal but also helps the negotiator to expand his or her repertoire of negotiation strategies (Brett & Gelfand, 2004). Behavioral dimensions of negotiation that bear on cultural differences are often referred to as "negotiation styles" (Faure, 2004), as each culture has its own negotiation style (Simintiras & Thomas, 1998). Indeed, at the cultural level, shared values create a social environment that guides members in choosing their negotiating behavior and that should lead to socially accepted outcomes (Tinsley & Madan, 1998). For example, a negotiator belonging to a collectivist culture tends to adopt a cooperative behavior while an individualist tends to be more competitive (Volkema, 2004). Culturalists have always stressed the importance of the human factor in negotiation. Negotiation, of course, is a set of techniques and methods, but it is above all a human adventure (Cervera & Kosma, 2016).

Despite the growth in international trade, globalization of the economy and the increase in international negotiations, research on intercultural negotiation remains normative and largely fragmented (Simintiras & Thomas, 1998). Most studies on culture-specific negotiator behavior and style agree that the cultural variable plays an explanatory role in understanding negotiator behavior and negotiation outcomes (Jolibert & Valsquez, 1989; Simintiras & Thomas, 1998; Chang, 2003; Faure, 2004; Brett & Gelfand, 2004; Volkema, 2004; Lim & Yang, 2007). Culture sets the boundary between an acceptable and unacceptable behavior. This boundary varies from one culture to another and means of action such as threats, lies, fait accompli, treason or corruption may or may not be considered legitimate (Faure, 2004). For example, the perception of ethical behavior differs according to the cultural characteristics of each negotiator (Volkema, 2004) and can thus positively or negatively affect the outcome of the negotiation. Thus, the perception and interpretation of an international context is influenced by stereotypes, historical memory and past personal experiences (Faure, 2004). This stereotype problem is so prevailing in international negotiations and needs to be studied (Lasrochas, 2004).

Research Methodology

Empirical Study

In view of determining Tunisian tourism and hotel industry stakeholders’ awareness of the attributes of negotiation and interculturality and their ability to take them into account in international negotiations, we conducted two empirical studies with a sample of officials in this sector. In the first study, a survey was carried out among 102 Tunisian tourism and hotel management officials who have experience in negotiation with foreign partners and customers. These managers work in travel agencies, tour operators, congress and travel agencies, and hotels. Representatives and correspondents of Tunisian tourism abroad were also included in this sample.

A two-section questionnaire was presented to them for completion in the presence of the researcher:

1. The first section of the questionnaire contains 20 items, 5 of which target the basics of negotiations, 5 the perception of power relationships in negotiations, 5 negotiation strategies and tactics and 5 the perception of the negotiation outcomes (Table 1).

2. The second section consists of 40 items (Table 2), which will inform us about the Tunisian negotiator's knowledge of intercultural rituals and behaviors and negotiation styles of five regions in the world, namely Western Europe (France, Italy and England), Africa, the United States of America, Eastern Europe and Asia (China and Japan).

The second study focuses on the European market, specifically Western Europe, since it is the main target of Tunisian tourism. A questionnaire with 35 items (Table 3) was completed by 80 professionals. The results should inform us about the ability of Tunisian negotiators to take into account the cultural factors of their main target market in the conduct of negotiations.

Since the survey used two questionnaires as investigation tools, the formulation of these questionnaires required a very thorough research in order to identify items that represent both negotiation and intercultural issues. As a result, a theoretical assessment of all the attributes of negotiation and interculturality, supposed to have an impact on the conduct and outcome of intercultural negotiations, has been conducted, by specifically referring to the work of (Hall,1976; Hofstede, 1991; Dupont,1994; Salacuse, 1999; Jolibert, 2001; Lasrochas, 2004; Usunier, 2006; Bobot, 2009).

To validate this questionnaire, it was tested by six experts in the field. The saturation effect was observed at the end of the sixth questionnaire. At this level, some modifications and corrections have been made, in particular with regard to the replacement of some theoretical concepts (distributive negotiation, integrative negotiation and interest-based negotiation) by practical concepts (Power relations in negotiation, cooperative negotiation, soft with people and firm on the problem, etc.) which are the negotiator's professional language.

Analysis, Results and Discussion

Negotiation Attributes

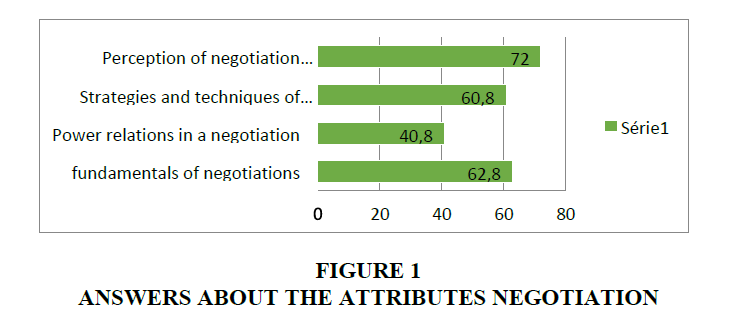

The results of the first study on negotiation attributes are reported in percentages in Table 1. They show that, in general, Tunisian negotiators are familiar with negotiation attributes. Indeed, the average score for correct answers is 62.8%. (To get an overview of the values obtained, we calculated the average scores of each negotiation attribute. The aim was to calculate the average of the five percentages of correct answers for each attribute.

| Table 1: Answers about the Attributes Negotiation | ||||||

| N° | Items | Right answer | Right answer in % | Incorrect answer in % | Average score of correct answers in % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamentals of negotiations | 1 | All negotiations are the same. | No | 91 | 9 | 62,8 |

| 2 | Negotiating and selling is the same | No | 74 | 26 | ||

| 3 | Negotiation is innate, it is not learned. | No | 71 | 29 | ||

| 4 | Negotiation is centered on price. | No | 40 | 60 | ||

| 5 | A good negotiation is to know how to sell. | No | 38 | 62 | ||

| Power relations in a negotiation | 6 | In a negotiation, involved parties always use balance of power. | Yes | 36 | 64 | 40,8 |

| 7 | Today, we do not negotiate anymore because the "Tour operators" have become too powerful. | No | 25 | 75 | ||

| 8 | In a negotiation, there is always a winner and a loser. | No | 47 | 53 | ||

| 9 | The asymmetry of power plays in favor of compromise. | No | 44 | 56 | ||

| 10 | In a negotiation, involved parties always use balance of power. | No | 52 | 48 | ||

| Strategies and techniques of negotiation | 11 | In a negotiation, it is always necessary to provide a fallback solution. | Yes | 79 | 21 | 60,8 |

| 12 | In a negotiation, you have to be lean on people and firm on the problem. | Yes | 75 | 25 | ||

| 13 | The expansion and openness technique contributes to a better compromise. |

No | 60 | 40 | ||

| 14 | When negotiating, we must always maximize our own interests. | Yes | 48 | 52 | ||

| 15 | The purpose of negotiation is always to do better than the partner. | Yes | 42 | 58 | ||

| Perception of negotiation results | 16 | To negotiate well, you have to know how to put yourself in the shoes of the other party. | Yes | 90 | 10 | 72 |

| 17 | A cooperation-based negotiation satisfies both parties. | Yes | 86 | 14 | ||

| 18 | The results of negotiations must be fair. | Yes | 51 | 49 | ||

| 19 | A good negotiation leads to a "win / win" outcome. | Yes | 82 | 18 | ||

| 20 | The results of a negotiation can forge relationships. |

Yes | 51 | 49 | ||

For example, for the fundamentals of negotiation, we add 91+74+71+40+38 and divide by five to obtain an average score of 62.8%). We can conclude that more than half of the negotiators know the fundamentals of negotiations. In addition, most of them gave incorrect answers for 2 attributes, which made us realize that the respondents showed confusion between negotiation and contract and between negotiation and bargaining.

The negotiators showed unawareness of the extent to which power relations could have a positive or negative effect on the conduct of a trade negotiation, since the average score of correct answers to the attributes of power relations in a negotiation is 40.8% (Table 1). For example, 75% no longer believe in negotiating with tour operators and consider them to have the last word because they have absolute power in the tourism market.

Negotiators are convinced that the conduct of a negotiation requires the use of an appropriate strategy. These strategies report to techniques and tactics that every professional negotiator should be aware of. This finding is observed in the average score of 60.8% of correct answers. Negotiations should normally lead to results that are satisfactory to the negotiating parties and that are fair and mutually beneficial with a win-win compromise. These conditions for the success of a trade negotiation are approved by Tunisian negotiators, as indicated by the 72% average score of correct answers in Figure 1.

Knowledge of Rituals and Behavioral Factors

As for respondents’ knowledge of negotiators' rituals and behavior, we note that out of 40 responses to intercultural behavior in negotiations, only seven obtained correct percentages (attributes n°1, 3, 6, 9, 10, 16 and 18: Table 2). They represent some attributes of European culture. This finding shows that the respondents are unaware of cultural imperatives and of how to behave during intercultural negotiations. Even more surprisingly, they ignore cultural imperatives of the regions that represent Tunisia's main target markets, like Western Europe. The different average scores show this well since they are all below the average of 50%.

| Table 2: Answers on Knowledge of Rituals and Behavioral Factors | |||||

| N° | Items | Right answer | Right answer in % |

Incorrect answer in % |

Average score of correct answers in% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Argue and contradict are both well-developed behaviors in French negotiators. | No | 52 | 48 | |

| 2 | French negotiators approach negotiations in power terms. | No | 36 | 64 | |

| 3 | French negotiators refuse to be subject to strict rules. | Yes | 58 | 42 | |

| 4 | French negotiators include in the schedule a lateness margin. | Yes | 43 | 57 | |

| 5 | French negotiators are more superfluous than experts (superficial knowledge). | Yes | 48 | 52 | 47,4 |

| 6 | You must send documentation to Italian negotiators. | Yes | 57 | 43 | |

| 7 | We need to force the conclusion of a contract with the Italians. | No | 26 | 74 | |

| 8 | Italians are emotional. | Yes | 44 | 56 | |

| 9 | Italians like to be informal when addressing people. | Yes | 51 | 49 | 46 |

| 10 | Italians ask for more in order to make concessions after. | Yes | 52 | 48 | |

| 11 | In case of disputes, the British will go to justice immediately. | No | 26 | 74 | |

| 12 | The British do not like to joke. | No | 28 | 72 | |

| 13 | The British like to make concessions. | No | 23 | 77 | |

| 14 | The British give considerable preference to women’s values. | Yes | 39 | 61 | 33 |

| 15 | The introductory phase is rather short with the British. | Yes | 49 | 51 | |

| 16 | Scheduling a tasting and a presentation of the product / service is essential to negotiate with African partners. | Yes | 50 | 50 | |

| 17 | An informal atmosphere is desirable during negotiations with West Africans (Senegal, Mali, Niger, Ivory Coast, etc.). | Yes | 39 | 61 | |

| 18 | The African partner is very sensitive at reception. | Yes | 65 | 35 | |

| 19 | Get straight to the business at hand with Africans. | No | 36 | 64 | |

| 20 | In Africa, staring at someone's eyes is a lack of respect. | Yes | 35 | 65 | 45 |

| 21 | In the USA, short negotiations are appreciated. | Yes | 47 | 53 | |

| 22 | Americans appreciate a gift before the negotiation. | No | 20 | 80 | |

| 23 | In the USA, do not discard women from the negotiation. | Yes | 49 | 51 | |

| 24 | Americans love to push through while doing business. | Yes | 17 | 83 | 29,6 |

| 25 | Americans negotiate in Group. | No | 15 | 85 | |

| 26 | Russians may lack punctuality. | Yes | 39 | 61 | |

| 27 | Russians like to bargain. | No | 19 | 81 | |

| 28 | Russians are patient and hard during negotiations. | Yes | 21 | 79 | |

| 29 | Personal connections determine negotiations with Russians. | Yes | 8 | 92 | |

| 30 | Gifts to Russians during negotiations are seen as attempts at corruption. | No | 27 | 73 | 22,8 |

| 31 | The Chinese are individualistic | No | 21 | 79 | |

| 32 | Be in a hurry to conclude the deal with the Chinese | No | 24 | 76 | |

| 33 | The Chinese use bargaining. | Yes | 11 | 89 | |

| 34 | For Chinese, the business may be concluded on a simple verbal agreement. | Yes | 7 | 93 | 15,4 |

| 35 | The Chinese do not hesitate to reject an agreement even if it is mutually concluded. | Yes | 14 | 86 | |

| 36 | In Japan, decision-making is done in groups | Yes | 47 | 53 | |

| 37 | The Japanese use balance of power. | No | 10 | 90 | |

| 38 | In Japan, we do not shake hands. | Yes | 38 | 62 | |

| 39 | The business card is presented with two hands to Japanese partners. | Yes | 35 | 65 | 32,4 |

| 40 | Gifts are appreciated in Japan | Yes | 32 | 68 | |

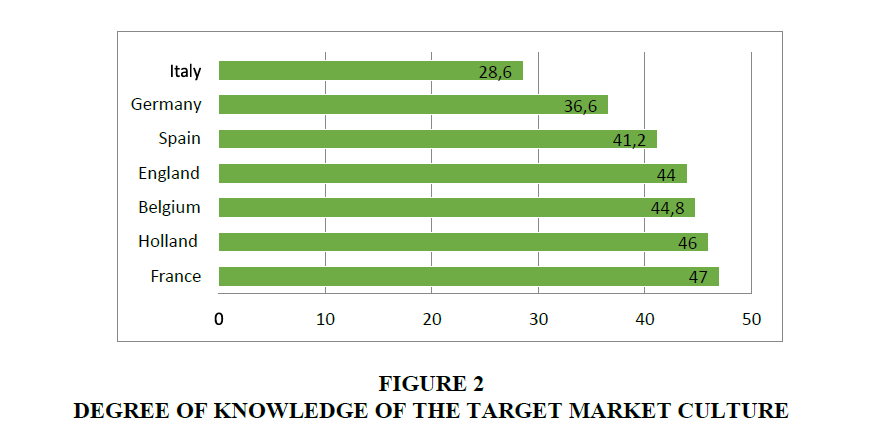

These unexpected results led us to survey a group of professionals who are used to negotiating with their partners and customers in Western Europe, as the main target market for Tunisian tourism. In this second study, we interviewed a group of officials with Western Europe as their main partners. This group consists of 80 individuals. Seven countries are selected, France, Italy, Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands. Thirty-five items (five items per country) representing the country’s respective culture made up the questionnaire for the eighty interviewees. These items have been selected from studies conducted on culture by experts in the field (Hofstede, 1991; Dupont, 1994; Lasrochas, 2004; Usunier, 2006; Bobot, 2009; Lavissière, 2017). The results of this second study are reported in Table 3.

| Table 3: Knowledge of Rituals and Behaviors of the Negotiators of the Target Market (Western Europe) | ||||

| N° | Items | Right answer | Right answer in % | Average score of correct answers in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The French negotiate for the cheapest outcome. | Yes | 75 | 47 |

| 2 | The French are very interested in thematic tourism. | Yes | 23 | |

| 3 | The French like to feel slightly superior to others. | Yes | 75 | |

| 4 | Argue and contradict are two well-developed attributes in the French negotiator. | Yes | 44 | |

| 5 | The French do not like the "all-inclusive" package. | No | 18 | |

| 6 | Italians are emotional. | Yes | 13 | 28,6 |

| 7 | We must force the conclusion of a contract with the Italians. | No | 19 | |

| 8 | We must send documentation to Italian partners. | Yes | 56 | |

| 9 | Italians appreciate being welcomed in their native language | Yes | 37 | |

| 10 | Italians appreciate nighttime entertainment. | Yes | 18 | |

| 11 | The British do not like to joke. | No | 41 | 44 |

| 12 | The British love heavy drinking evenings. | Yes | 37 | |

| 13 | Ecology-wise, the British attach great importance to recycling. | Yes | 25 | |

| 14 | The English do not attach importance to their dress. | No | 30 | |

| 15 | The British are discreet and pragmatic. | Yes | 87 | |

| 16 | Humor is tolerated during the first meetings with the Germans. | No | 41 | 36,6 |

| 17 | The Germans give accurate answers. | Yes | 90 | |

| 18 | Germans are sensitive to be welcomed in their language. | Yes | 15 | |

| 19 | The handshake is usual in German. | Yes | 12 | |

| 20 | Germans appreciate comfort. | Yes | 25 | |

| 21 | The meaning of hospitality is important in Belgium. | Yes | 14 | 44,8 |

| 22 | Belgians seek individualized answers. | Yes | 35 | |

| 23 | The weekend is not sacred in Belgium. | No | 50 | |

| 24 | Belgians are cheerful and friendly. | Yes | 50 | |

| 25 | Belgians are very demanding as to the quality of the offered services. | Yes | 75 | |

| 26 | The Spanish are generous. | Yes | 87 | 41,2 |

| 27 | The Spanish like to be addressed in formal terms. | No | 25 | |

| 28 | The Spanish are punctual for meals. | No | 15 | |

| 29 | The Spanish are sensitive to a personalized welcome. | Yes | 52 | |

| 30 | The Spanish like to discover their destination alone. | Yes | 27 | |

| 31 | The Dutch respect commitments. | Yes | 88 | 46 |

| 32 | The Dutch do not accept speaking to them in English. | No | 24 | |

| 33 | In the Netherlands, there is a strong preference for women's values. | Yes | 38 | |

| 34 | The Dutch prefer to be welcomed in their language. | Yes | 63 | |

| 35 | The Dutch always negotiate for the lowest costs. | No | 17 | |

The analysis of the results of the second survey reveals inadequacies in the respondents' knowledge of the partners' culture. Out of 35 items, only twelve are acceptable percentages, greater than or equal to the average: 50% (items 1, 3, 8, 15, 17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 29, 31 and 34: Table 3). Europe is in fact the main market for Tunisian tourism, in addition, it is a continent that is quite geographically close. This leads us to assume that, normally, the intercultural dimension in trade negotiations between Tunisian and European tourism professionals should not pose any problem. The results of this survey show the opposite.

Not all scores reached the average of 50%. Italy, despite its geographical proximity to Tunisia, and especially with the large flow of Italian tourists in recent years, comes in last place with an average score of 28.6%. France is in first place with a score very close to that of the Netherlands, which is in third place. These results are reported in Figure 2.

Conclusion

The literature on international negotiation and interculturality is abundant, but problems on the interaction between their respective variables seem very rare. An exception is the few studies that focused on a few topics in an attempt to highlight the importance of cultural factors in the conduct and success of intercultural negotiations. We also note that studies with professionals (negotiators, businessmen, tourism service providers, exporters, hoteliers, etc.), who could inform us about the practice of intercultural negotiation, in particular the difficulties and failures encountered in this field, are rare to understand the scope and importance of each cultural variable in international negotiations, and thus establish a negotiation model that includes all the cultural factors that have an impact on the conduct and success of negotiations.

The literature review in this paper showed that research on negotiations and interculturality is evolving. In particular, the methodological sphere is gaining tandem with the introduction of quantitative studies, particularly comparative and transcultural research designs. In addition, this is true at the conceptual level, with the shift from ideological and polemical perspectives on negotiations to pragmatic ones. Our study of Tunisian tourism and hotel professionals have enabled us to highlight three main observations. The first relates to knowledge of negotiation attributes in general, i.e. the attributes that characterize all forms of negotiations (commercial, international, collective, business, etc.). At this level, Tunisians have shown themselves to be experts about most of the attributes - the fundamentals of negotiations, the balance of power in a negotiation, negotiation strategies and techniques and the perceptions of the negotiation outcomes.

Then, we can conclude that, in general, they do not have any problems in conducting an international negotiation. The second observation is the ritual and behavioral factors in international negotiations, too few factors have had correct answers. It therefore seems that interculturalism is not a priority in the minds of Tunisian tourism professionals. The third observation relates to a dimension that we consider important in international trade negotiations. This is knowledge of the cultural imperatives of the main partner, i.e. the target market, with which we regularly negotiate and with which we have very important trade and business relations. In our study, this is the European market for which too few factors have had correct answers.

The results of our study also showed that intercultural issues, despite their importance in international trade relations and their impact on negotiations, do not seem to find their rightful place in the minds of Tunisian tourism professionals. Further work is needed to show that the success or failure of international negotiations may depend to a large extent on the knowledge, or respectively neglect, of the cultural factors of the partner. Our results have shown that professionals and researchers should show an interest in collaborating with each other to work on subjects and themes related to international negotiation. Nowadays, this interest represents a legitimate emotive to bring academic research and actors in the tourism sector closer together. Intercultural tourism negotiations should now favor the integrative nature and reasoned modes of Fisher and Ury (Chamoun et al., 2018).

As for future research, two directions can be signaled. The first is to work on a specific culture and try to identify as many cultural attributes as possible. These attributes can represent both negotiators' rituals and their behavior during intercultural negotiations. The second relates to the methodology to be used to survey managers of the tourism and hotel sector. It would be interesting to use qualitative techniques with in-depth interviews that allow respondents to express their views on the theme addressed and to give their views on the difficulties encountered while conducting intercultural negotiations and to share anecdotes on negotiations with foreign partners to learn from them.

However, two main limitations are worth noting. The first relates to the sample size of the target market. Indeed, 80 interviewees from 5 countries are considered quite limited in an international study. The main reason for this limitation is the difficulty of finding an opportunity or event (symposium, fair, congress, etc.) to get closer to foreign interviewees and convince them to be involved in a survey. The second relates to the ritual and behavioral dimensions of the negotiators of the target market. Indeed, in order to simplify the questionnaire (already consisting of 40 questions), we have limited ourselves to five items per country. This number is small enough to determine a culture. We should work on a more complete and exhaustive list of items likely to provide us with more information on the cultures of the considered countries.

References

- Adler, N. (1986). International Dimensions of Organisational Behaviour. Kent Publishing.

- Bond, M.H. (1986). The Psychology of the Chinese People. Hong Kong, Oxford University Press.

- Bobot, L. (2009). Méthodes d’enseignement de la négociation. Négociations, 12, 257-273.

- Brett, J. & Gelfand, M. (2004). Effet de la culture sur le style de négociation: trois cas insp irés d’ailleurs. Revue Française de Gestion, 153, 201- 210.

- Camilleri, C. (1995). Relations et apprentissages interculturels: réflexion d’ensemble. Relations et apprentissages interculturels. Paris: Armand Collin, 135-144.

- Cervera, G. & Kosma C. (2016). La négociation internationale et interculturelle, de la connaissance de soie à la rencontre de l’autre, Editeur Genie Des Glaciers, collection les Mementos.

- Chamoun, N.H., Rabadán, F., Hazlett, R.D., & Alonso, R.I. (2018). From distributive & integrative to trans-generational negotiations. A statistical approach. Négociations, (1), 75-100.

- Chang, L.C. (2003). An examination of Cross-Cultural Negotiation: Using Hofstede Framework. Journal of American Academy of Business, 2, 567.

- Debabi, M. (1997). L’impact des variables culturelles sur le déroulement et la conduite d’une négociation commercial. Cahier de recherche, E.S.C Lille.

- Dellech, D. & Debabi, M. (2017). La négociation interculturelle: défi des approches concurrentes et diversité des paradigmes. Question(s) De Management, 19, 73-82.

- Dupont, C. (1994). La négociation: Théories, pratiques et applications, Dalloz, Paris.

- Dupont, C. (2003). Le risque dans la négociation, Cahier de recherche, 3, Laboratoire d’études appliquées et de recherche sur la négociation, ESC Lille.

- Faure, G.O. (1999). L’approche chinoise de la négociation: stratégies et stratagèmes, Gérer et Comprendre, Annales des Mines, juin, 36-48.

- Faure, G., Laurent, M., Touzard, H. & Dupont, C. (2000). Négociation: Situations, problématiques et applications, Edition Nathan, Dunod, Paris.

- Faure, G.O. (2004). Approcher la dimension interculturelle en négociation internationale. Revue Française De Gestion, 6, 187-199.

- Hall, E.T. & Hall, M.R. (1990). Understanding cultural differences. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural.

- Hall, E.T. (1976). Beyond Culture. Anchor Press/Doubleday, Garden City, NY.

- Henriquez, S. (2000). La communication interculturelle: entre ethnocentrisme et relativisme. Europe Plurilangues, 19-30.

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Culture and organizations: Software of the mind, McGraw Hill, London. Jolibert, A. (2001). Pratique de négociation en Malaisie. Décision Marketing, 24, 49-57.

- Jolibert, A. & Velazquez M. (1989). La négociation commerciale, Cadre théorique et Synthèse. Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 4, 51- 72.

- Khakhar, P. & Rammal, H. (2013). Culture and business networks: international business negotiations with Arab managers. International Business Review, June, 578-59

- Lasrochas, P.A. (2004). Les techniques et tactiques en négociation. Congrès de Vienne.

- Lavissière, A. (2017). Négocier en Afrique aujourd’hui: ce qu’on ne sait pas…. The conversation, Academic rigour, journalistic flair, March 19.

- Lenclud, G. (1991). L’universel et le relatif, A propos de l’ouvrage de Tzetan Todorov, 17, 53- 62.

- Leroux, E. & Pupion, P.C. (2014). Management du tourisme et des loisirs. Vuibert, Paris.

- Lim, J. & Yang, Y.P. (2007). Enhancing Negotiators' Performance with Computer Support for Pre-Negotiation Preparation and Negotiation: An Experimental Investigation in an East Asian Context. Journal of Global Information Management, Hershey, 1, 18- 25.

- Nicklas, H. (1995). Identité culturelle et conflits entre les cultures, In Abdallah-Pretceille M. et Thomas A. (Eds.). Relations et apprentissages interculturels. Armand Colin, Paris. 35-46.

- Reynolds, N., Simintiras, A. & Vlachou, E. (2003). Present knowledge and direction for future research.

- Saidi, K. & Debabi, M. (2016). Le bluff et la déformation de information dans la négociation commerciale.

- Salacuse, J.W. (1999). Intercultural negotiation in international business.Group Decision and Negotiation, 8, 217- 36.

- Simintiras, A.C & Thomas, A.H. (1998). Cross‐cultural sales negotiations: A literature review and research propositions. International Marketing Review, 15(1), 10-28.

- Tinsley, C. & Madan, M.P. (1998). Negotiating in the United States and Hong Kong. Journal of International Business Studies Washington, 4, 711.

- Usunier, J.C. (2006). Relevance in business research: the case of country-of-origin research in Marketing.

- Volkema, R. (2004). Demographic, cultural, and economic predictors of perceived ethicality of negotiation behaviour, A nine-country analysis. Journal of Business Research, 57, 69- 78.

- Zartman, W.I. (2004). Concevoir la théorie de la négociation en tant qu’approche de résolution de conflits économiques. Revue Française de Gestion, 153.