Research Article: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 1

Innovative Leadership Preparation: Enhancing Legal Literacy to Create 21st Century Ready Principals

Kristen A Gilbert, Augusta University

Keywords

Preparing 21st Century-Ready Educational Leaders, School Law, Legal Literacy, Immersive Simulation, Augmented Reality, Situated Learning, Critical Pedagogy.

Introduction

The signing into law of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) 2001 reauthorized the longstanding Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA, Jorgensen & Hoffman, 2003) and immensely changed the educational landscape. This landmark event ushered in an era of accountability for students, teachers and administrators and notably caused the job of principals to increase in complexity and pressures (Boyland, Lehman & Sriver, 2015). Growing evidence suggesting that principals both directly and indirectly affect academic achievement, combined with these increasing accountability measures, translate to potentially serious consequences for principals if they fail to find a way to adeptly address the multi-faceted demands of their jobs (Davis et al., 2005; Voelkel, Johnson & Gilbert, 2016). The most recent re-authorization of ESEA, the Every Student Succeeds Act, affords flexibility to state and local districts to decide how to raise student achievement – a move that may unwittingly place more accountability and pressures on educational leaders (Voelkel et al., 2016) and calls for heightened awareness to enhancing their preparation.

Legal literacy, a term used to describe competence in school law knowledge and the ability to use deliberative tools to properly apply it (Militello, Schimmel & Eberwein, 2009) is both central and essential to meeting the demands of accountability legislation (Painter, 2001). Strong legal literacy in principals is recognized as a powerful fulcrum in leading large-magnitude reform and necessary in effective day-to-day transactions of schools (Davis et al., 2005; Pauken, 2012). However, principals typically do not demonstrate proficiency in this realm (Milittelo et al., 2009; Painter, 2001; Pauken, 2012). When principals are non-conversant in school law and are faced with perplexing problems, they frequently default to a less nuanced, piecemeal approach to applying law in search of formulaic answers to complex challenges. These approaches do little to challenge the status quo and deconstruct the structural inequities that perpetuate the achievement gap. Furthermore, steady increases in litigation against schools shift principals’ focus away from important work and overall school improvement efforts and yet, avoiding litigation is challenging. School law is not static and policy and law development often lag behind contemporary issues. Adding to these challenges, education is fraught with tensions that exist between competing interests. While most principals may be capable of identifying major cornerstones of school law, many are not prepared adequately to use their legal literacy to support school improvement through both in-the-moment and deliberate decision-making (Painter, 2001; Pauken, 2012). This lack of strong legal literacy hampers their efforts to fulfil schools’ missions (Painter, 2001) and invites increased scholarly attention to the conversation of how to improve the effects of school law courses.

While better preparation in the realm of school law would be one approach to increasing legal literacy and consequently school improvement efforts, institutions struggle in this endeavour (Hoff, personal communication, 2015). In general, producing principals who are prepared to take on the task of leading in the 21st century is fraught with persistent and pervasive problems (Levine, 2005). This lack of proper preparation promotes turnover and makes it challenging to improve schools (Jensen, 2014). Arming principals with strong legal literacy would provide them with a broader foundation of the tools necessary to avoid attrition and challenge the dominant cultures that perpetuate structures, policies and practices that promote unearned privilege and widen the achievement gap. Immersive simulation is posited by many prominent scholars to be a possible solution to challenges of adequately preparing educational leaders (Johnson et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2016). Immersive simulation in this context refers to a technology enhanced role play that makes use of augmented reality. In immersive simulation, aspiring and current educational leaders interact with an avatar or avatars and role-play common and yet challenging scenarios that one could encounter in school settings. This type of role play allows for a transfer of theory to practice and the honing skills in real-to-life scenarios in a risk-free manner. While many studies on the use of immersive simulations exist with pre-service teachers, there are very few regarding its use with educational leadership preparation and none in the area of its use with school law. The purpose of this multiple-methods study is to examine: a) if the use of technology enhanced simulations, (heretofore referred to as immersive simulation) can change aspiring principals’ knowledge and b) how principals’ value learning through immersive simulation. This study measured aspiring principals’ level of legal literacy before and after participation in immersive simulation and asked an open-ended question regarding the on the use of immersive simulation as an adult pedagogical tool.

Literature Review and Conceptual Model

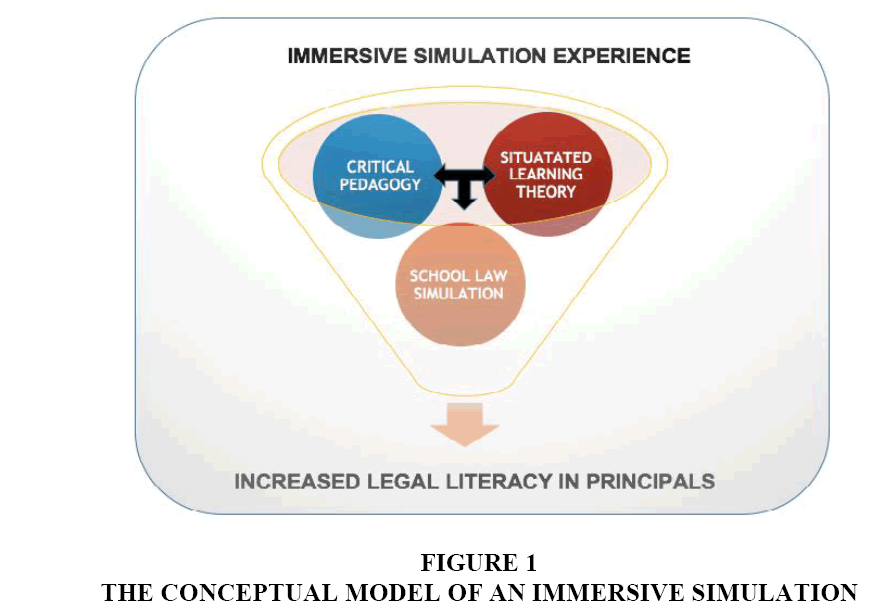

This literature review explored three constructs: the importance of effective 21st century principals and pervasive challenges in adequately training them, the importance of strong legal literacy to promote school reform and the use of simulation as a training and professional development tool in education. The intersection of these constructs makes a compelling case for increasing legal literacy through the use of immersive simulations as one piece of the school reform puzzle particularly when viewed through the lens of situated learning theory and critical pedagogy.

Effective 21st Century Principals

A comprehensive meta-analysis of over 5,000 studies, covering a nearly thirty-year period, concluded “that there is, in fact, a substantial relationship between leadership and student achievement...[With] the average-effect size between leadership and student achievement of 0.25” (Waters et al., 2003). Equally important, Waters et al. (2003) concluded that principals who are not effective also have a corollary and opposite effect on academic achievement. This claim was bolstered in a landmark report for the Wallace Foundation with researchers stating, “school leadership is second only to classroom teaching as an influence on pupil learning” (Leithwood, Louis, Anderson & Wahlstrom 2004, p. 4). Subsequent research has been consistent in underscoring the importance of principals in affecting academic achievement (e.g. Davis et al., 2005; Davis, Leon & Fulz, 2013; Darling-Hammond, LaPointe, Meyerson, Orr & Cohen, 2007; Darling-Hammond, Meyerson, LaPointe & Orr, 2010) and the inability for schools to improve in their absence (Waters et al., 2003). To effectively promote academic achievement and meet the demands of leading in the 21st-century, strong legal literacy – knowledge plus their ability to apply it – is necessary (Davis et al., 2005; Pauken, 2012). Unfortunately, it is widely acknowledged that the training principals receive is often inadequate to prepare them for this daunting task (e.g. Darling-Hammond et al., 2007; Farkas, Johnson, Duffett, Foleno & Foley, 2001; Levine 2005). In a report prepared for the Wallace Foundation on the effectiveness of principal preparation programs, principals and scholars alike deemed traditional programs “out of touch” (Farkas et al., 2001, p. 31) with the day-to-day challenges of leading 21st-century schools. These challenges demand diverse skill sets grounded in content knowledge (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007; Davis et al., 2005). This is necessary for analyzing complex situations, making judicious and effective decisions at a rapid pace and transforming schools into learning organizations capable of yielding competent, well-informed citizens (Davis et al., 2005). However, principals enter the field ill-equipped to transfer their theoretical learning to the rapid pace of the decision-making and the ability to solve the complex problems they face (Oplatka, 2009). In discussing the knowledge and skill set needed of 21st-century-educational leaders, Levine (2005) stated that “few of today’s 250,000 school leaders are prepared to carry out this agenda” (p. 12). In addition, Darling-Hammond and her colleagues (2007) reported 80% of superintendents and 69% of principals believe university programs produce principals who are ill-prepared. In part, the criticism has been directed at a lack of authentic learning opportunities in which to apply content knowledge and develop and hone skills (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007; Darling-Hammond et al., 2010; Farkas et al., 2001).

In reaction to the stated failure of traditional principal preparation programs and with the development of highly effective principals as one of the top priorities of Race to the Top legislation (Wei, Darling-Hammond & Adamson 2010), institutions have adjusted their programming to include the performance-based and job-embedded opportunities that marry knowledge and action with real-world experiences (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007). Theoretically, these sustained and in-depth field experiences allow for exposure across a vast domain of necessary skills and content knowledge; however, quality control and consistency in exposure have been identified as weaknesses of these performance-based models (Darling-Hammond et al., 2010).

Despite this scrutiny, scholars and practitioners do not dispute the need for authentic learning opportunities that facilitate transfer of knowledge and skills to real-world applications without a great deal of elapsed time between the actual learning and application – a term Dede (2009) calls the “near-transfer” (p. 67) of skills. Consequently, the current trend is still toward preparation that allows aspiring leaders to apply content knowledge and engage in skill development through the participation in authentic leadership opportunities. However, inconsistent quality control and the limitation of uniform exposure to content taught in favour of more heuristic methods provide inadequate preparation of the necessary skills to use legal literacy as a tool for school reform (Nixon, personal communication, February 4, 2015). Given these persistent and pervasive challenges in preparing principals, even with performance-based, job-embedded models, many scholars have called for the use of pedagogical tools such as simulation to provide authentic, risk-free opportunities to practice execution of complex and nuanced decision-making (Anderson, 2014; Johnson et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2016).

Legal Literacy in School Law

In school systems, although a variety of educational leaders are responsible for sound legal decision-making that promotes the efficient operation of schools, principals are central to these day-to-day transactional processes, as well as large-magnitude reform efforts. Possessing a high degree of legal literacy not only supports the proper oversight of these transactional processes (Gary, 2015), it aids in the deconstruction of the status quo, thereby promoting 21st-century principals who are effective as change agents (Pauken, 2012).

Principals make both deliberate and in-the-moment decisions daily that, at best, may interfere with their ability to focus on leading schools and at worst, could have far-reaching ramifications on their employability (Pauken, 2012). This may explain why school law courses are generally most valued by principals, with 80% of those surveyed indicating a high level of value and relevance to their practice – a rating nearly 20 percentage points higher than their average ratings of value of all other principal preparation coursework (Levine, 2005). In an introductory letter to a report for the Wallace Foundation on preparation of school leaders, President Christina DeVita stated that, among other things, principals are expected to be “expert overseers” (Davis et al., 2005, p. 1) of legal and policy matters. With approximately 60% of principals facing lawsuits in the 21st century (Gary, 2015), not only is attention shifted away from important work, the fear of lawsuits gives principals reason for pause. This interferes with their ability to provide the best possible education to students and can result in a loss of programming, hesitancy to mete out discipline and turnover of principals (Militello et al., 2009). While there is no research correlating the degree and quality of the training to frequency of litigation (Militello et al., 2009), scholars posit that risk of possible culpability in a lawsuit can be reduced through increased legal literacy aimed at challenging structures, policies and practices that further disadvantage the very students for whom schools struggle to serve well (Militello et al., 2009; Painter, 2001; Pauken, 2012).

Principals want to behave in an ethical manner and desire to be prepared to address issues of school law, particularly those which do not readily lend themselves to clear and formulaic responses (Painter, 2001). Given that it is impossible to define a definitive body of knowledge for school leaders, teaching them to think critically and to rely on their legal literacy as a fulcrum for school reform (Pauken, 2012), may be the best strategy for producing more adept 21st century principals. As such, developing principals who are capable of using legal literacy to improve schools deserves more attention. University preparation programs can achieve the aim of increasing legal literacy by teaching principals to think critically when accessing school law knowledge (Pauken, 2012).

Use of Immersive Simulations

The proliferation of affordable and user friendly technology has encouraged the use immersive simulation in virtually every aspect of American life. Schools are no exception as they have turned to technology to address a variety of challenges including adequately preparing educators for the needs of 21st century schools (Bradley & Kendall, 2015; Johnson et al., 2011). For example, immersive simulation, when properly designed, adds value to a variety of learning situations, particularly leadership (Aldrich, 2009) as it has “potential for all fields where rapid information transfer is critical” (Yuen, Yaoyuneyong & Johnson, 2011, p.124). When designed to combine feedback with deliberate practice in educational and professional settings, immersive simulation supports the transfer of content knowledge, skill acquisition and maintenance of knowledge; heightens decision-making skills; and promotes practice in and mastery of sequencing procedures (Dede, 2009). As such, technologies based in augmented and virtual realities were ranked the highest among the panel of experts as a pedagogical tool in higher education by the Horizon Report in 2011 (Johnson et al., 2011) with the most current report (2016) identifying trends for educational applications of technology and their potential impact on universities’ core missions.

Increasingly, immersive simulations are seen not only as appropriate teaching and learning tools, but essential in the field of teacher preparation with the literature supporting and underscoring their potential benefits (Badiee & Kaufman, 2015; Bradley & Kendall, 2015, Johnson et al., 2016). The concept of using immersive simulation to provide authentic learning opportunities specifically for aspiring educational leaders has also begun to appear in the literature (Storey & Cox, 2015; Voelkel et al., 2016). Immersive simulation may be a possible solution to identified shortcomings of traditional educational leadership programs and the variable exposure and range of quality experienced in current performance-based programming (Levine, 2005; Storey & Cox, 2015; Voelkel et al., 2016). In Levine’s (2005) critique of the university leadership preparation programs, he noted:

Alumni and students favoured active learning pedagogies that knitted together the clinical and academic strands of their education. Especially popular were simulations and case studies, which are employed more frequently in educational leadership than in any other education school subject area, but which are still not as common as they could be. (p. 41). In this quote, Levine highlights the noted effectiveness of pedagogies such as simulations to prepare educational leaders and notes the need for increased usage of such pedagogies.

Most recently, a review of the literature was conducted which outlined the uses of immersive simulation through one of the most widely used platforms for training pre-service educators in a broad range of scenarios (Bradley & Kendall, 2015). This review revealed the clear majority of use to be in pre-service teaching applications, although at the time of this publication, a few studies had been conducted using immersive simulations to train educational leaders. However, no results for the use of immersive simulation to provide training or professional development in the realm of school law were indicated in this platform or any others reviewed in the literature.

Conceptual Model

Situated learning theory and critical pedagogy serve as the theoretical foundations for this study. An underlying tenet of situated learning theory asserts that separating tasks of learning and doing fragments the learning process and hinders transfer of knowledge and skills (Dede, 2009). For this reason, situated learning theory is commonly drawn on when examining or attempting to narrow the gap between knowledge and practice (Brown, Collins & Duguid, 1989). Situated learning theory is educative in this study because immersive simulations, when properly designed and executed, join the act of learning and doing to mimic real-world experiences effectively and thus promote transfer of knowledge and skill acquisition (Dede, 2009; Yuen et al., 2011). Critical pedagogy, which grows from Freire’s (2000) ideas of learner-centered theory and the Frankfurt school of critical social theory, prompts educators to be mindful of the social structures which sometimes interfere with action regardless of content knowledge and ability to apply it. Following from Giroux’s (1991) read on Freire’s learner centred theory, critical pedagogy is instructive in the design of this study as learning is not simply situated but also grounded in the context of social power structures. Learning is thus political, which influences action or lack thereof, in the application of knowledge (Giroux, 1991). Since principals’ application of school law is frequently influenced by the status quo or dominant values of a culture (Gray & Streshly, 2008), it is important to afford opportunities for communities of learning, much like PLCs, to engage in meaning making that allows cohort learners opportunities both to deconstruct and challenge the status quo. This is accomplished through the design of immersive simulation guided by common elements of situated learning-grappling, scaffolding, coaching and reflection and critical pedagogy that enables multiple perspectives created by learning communities, who together can deconstruct dominant cultures of behaviours and practice the necessary skills to deconstructing the status quo (Storey & Cox, 2015). Figure 1 presents the conceptual model, of an immersive simulation designed in this manner.

Darling-Hammond et al. (2007), when examining how to train educational leaders effectively, remind us of the importance of constructing learning environments that allow for communities of practice who support grappling with ideas and meaning making through the process applying theory to practice. This includes learning which incorporates opportunities to: learn with and from one another; grapple with ideas to make meaning; be exposed to complex, integrated and realistic, problem-solving scenarios that are scaffolded to individual’s needs; receive coaching to promote learning in the zone of proximal development; and promote near-transfer of skills. Properly designed immersive simulations can create this ideal learning environment. The primary aims of this study were to test the hypothesis that participation in immersive simulation can change principals’ knowledge of school law regardless of the type of school law preparation and determine if immersive simulation is perceived as a valuable pedagogical tool by participants. The overarching research questions and hypotheses that guided this study are as follows:

1. Regardless of the type of school law preparation, to what degree, if any, does participation in immersive simulation change aspiring principals’ knowledge of school law in high-rate litigation areas?

H1: Legal literacy of aspiring principals will increase after participation in immersive simulation designed with major tenets of situated learning theory and critical pedagogy.

Ho: Legal literacy of aspiring principals will not change after participation in immersive simulation designed with major tenets of situated learning theory and critical pedagogy.

2. How do aspiring principals value the effect of immersive simulation on their school law content knowledge?

Methods

Data Collection Procedures and Analysis

Using a quasi-experimental pre-post survey research design, data were gathered to determine if there was a change from pre- to post-test in the legal literacy of aspiring principals after participation in immersive simulation for research question one. Dependent samples t tests were used to test the null hypotheses that legal literacy of aspiring principals would not change after participation in immersive simulation. Because this study lacks sufficient sample size to conduct a multivariate analysis (Mertler & Vannatta, 2005), pair-wise comparisons were employed and the Bonferroni correction applied to the p values to correct for the inflated family-wise error rate. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to calculate dependent sample t tests statistics and p values. Effect sizes were calculated using an online calculator to ascertain Cohen’s d (http://www.uccs.edu/~lbecker/).

A questionnaire consisting of one open-ended item was administered to ascertain the value participants assign immersive simulations’ effect on their learning. Data were analysed using open, axial and selective coding scheme. This method was used to develop and connect categories that allowed me to theorize about the experiences of research participants’ perceptions in immersive simulation. While coding data gathered a constant comparative method served as an internal reliability measure since the process allowed me to continuously re-examine the data and consciously be aware of and bracket biases at each step. Credibility in the process was promoted through: prolonged engagement with the data through a constant comparative method, mitigation of interpretative bias by making sure the data reflect the findings and the use of quotations from the research participants which reflect support for emerging themes.

Sample

Georgia has undergone significant changes in their educational leadership programs and has been acknowledged as being innovative in their approach (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007). As such, this study relied on a purposive sample drawn from a pool of participants who were enrolled in graduate programs at two small institutions in Georgia. Similar to other institutions in Georgia and in the United States, these institutions require a law class for aspiring principals and devote a component of their programming to job-embedded, performance-based experiences. The sample consisted of graduate students who met one or more of the following three criteria: 1) students entering an educational leadership program at the university, 2) those who had completed a course in school law, or 3) those who were currently participating in (or had participated in) job-embedded leadership training (n=43). Because the study aimed to investigate value added to aspiring principals’ school law knowledge, it was desirable to exclude participants who may have already developed a high degree of legal literacy through several years of experience (3 or more), serving as an assistant principal or principal.

Procedure Recruitment

Participants were recruited from each university through educational leadership and school improvement courses. News posts for online courses, emails to students and when possible, in-class visits served as recruitment efforts. While participation in the immersive simulation was not anonymous, data gathered were anonymized. To promote anonymity, data were reported in aggregate form only.

Instrumentation

The instrument used in this study was a modified version of the Principals’ Education Law Survey (Militello et al., 2009). This instrument was modified to include only items relevant to legal literacy in the three high-rate litigation areas of student rights, employee rights and the separation of church and state. High-rate litigation areas were determined by litigation topics current in the literature review that was susceptible to much higher rates of litigation than others. A review of Georgia’s largest and most comprehensive newspaper, the Atlanta Journal Constitution (AJC) was also conducted using a keyword search of the archives from 2007 through 2015. Combinations of the keywords litigation, schools, lawsuits and education revealed similar trends. One hundred and thirty-four separate lawsuits against school districts were reported on by the AJC in the last eight years. Of the 102 cases regarding Pre-K-12 education, litigation against schools fell primarily into three clusters. Student rights and other issues concerning students comprised 53% of the cases, while employee rights and disputes accounted for 13% and religion 7% of the cases. The remaining 27% of cases were disparate in nature (e.g. school board committee members suing the governor over his decision to remove them from their seats, sex abuse by coaches and teachers, charter school legislation, parental rights to carry weapons in schools, etc.).

Because this survey was intended to assess aspiring leader’s knowledge, questions also were reworded to reflect the behaviours of administrators with a focus on the ways in which they have the legal rights to act. Validity of the content of the modified version of the survey was determined through review by an expert panel of three assistant principals, one principal, two central office personnel with experience in school law and two school law professors at nearby universities. Cognitive interviews were performed following concurrent and retrospective think-alouds, probing and paraphrasing, after which each participant was asked to provide feedback about how well the instrument measured the content it was designed to measure. Adjustments were made accordingly before administration to research participants.

Results

Demographic data were gathered through a set of survey questions. Frequency statistics were calculated to summarize the demographic data (Table 1). Of the 43 research participants, 67.4% identified as women; 39% reported they were general education teachers, 4.7% special education teachers, 14% instructional coaches, 9.3% athletic directors, 30.2% current assistant principals and 4.7% as office personnel.

| Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N=43) |

|||||

| Characteristics | n | % | Characteristics | n | % |

| Sex | School Law Training | ||||

| Female | 29 | 67.4% | Course 19 |

44.2% | |

| Male | 14 | 32.6% | Job-Embedded | 5 | 11.6% |

| None Reported | 19 | 44.2% | |||

| Roles in Schools | |||||

| Teachers | 17 | 39.5% | Rating of School Law Training | ||

| Special Educators | 2 | 4.7% | Course | ||

| Instructional Coaches | 6 | 14% | Outstanding & Very Good | 16 | 37.2% |

| Athletic Directors | 4 | 9.3% | Good & Fair | 12 | 29.7% |

| Assistant Principals | 13 | 30.2% | Less than Adequate | 0 | 0.0% |

| Central Office | 2 | 4.7% | Job-Embedded | ||

| AP / AD | 3 | 7.0% | Outstanding | 0 | 0.0% |

| Teacher & Special Ed | 1 | 2.3% | Very Good & Good | 10 | 23.2% |

| Other | 3 | 7.0% | Fair & Less than Adequate | 3 | 7.0% |

In school law training, 44.2% indicated they had received training in school law through a course at a university. Of those who had taken a university course in school law, 57.1% rated their course as outstanding or very good and 42.8% assigned a rating of good or fair. In the job-embedded area of school law training, 11.6% of participants reported this as their only school law training. Of those who had participated in job-embedded training, 76.9% of this group rated their job-embedded experience as very good or good, with 23.1% assigning a rating of fair or less than adequate.

Research Question One

Data were collected using the Modified Version of the Principals’ Education Law Survey to answer the first research question: Regardless of the type of school law preparation, to what degree, if any, does participation in immersive simulation change aspiring principals’ knowledge of school law in high-rate litigation areas? Overall knowledge scores were calculated using a ratio of correct answers to total number of questions. Research participants were instructed that if they felt that they had no basis for an educated guess on the knowledge subtests, they should choose “unsure.” Those marked as “unsure” were coded as incorrect answers. The Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for the family-wise error rate and resulted in a critical value of p<0.01. Overall knowledge ranged from 0.33 to 0.83 on the pre-test and from 0.37 to 0.90 on the post-test. A dependent samples t test indicated a significant increase from pre- to post-test (t (42)=7.865, p<0.01), as the mean increased from M=0.52 (SD=0.14) to M=0.72 (SD=0.12). This change is qualified by a very strong effect size, d=1.58 and indicates that the legal literacy of aspiring principals increased after participation in immersive simulation. To develop a deeper understanding of the observed differences and aid in the interpretation of overall knowledge increases, further analyses were conducted to determine if there were differences in the changes in the subtests of school law knowledge in the three high-rate litigation areas of student rights, employee rights and separation of church and state. The mean pre- and post-test scores for each subtest are presented in Table 2.

| Table 2 Changes in Overall Knowledge and Self-Efficacy |

||||||

| Overall Changes | Pre | Post | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | d | |

| Overall Knowledge | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.12 | 7.865 | 1.58 |

| Student Rights | 0.48 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.14 | 6.413 | 1.17 |

| Employee Rights | 0.59 | 0.15 | 0.68 | 0.14 | 2.925 | 0.66 |

| Separation of Church and State | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.77 | 0.14 | 8.591 | 1.80 |

Dependent samples t tests were calculated and indicated a significant increase in knowledge in each area, student rights: (t (42)=6.413, p<0.01, d=1.17), teacher rights: (t (42)=2.925, p<0.01, d=0.66) and separation of church and state: (t (42)=8.591, p<0.01, d=1.8). When taken together, these results indicate that the observed change in overall knowledge between pre- and post-tests is both statistically significant and practically significant. This implies that participation in a simulated experience may be an effective way to increase principals’ legal knowledge.

Research Question Two

Qualitative data analysis of open-ended survey questions was employed to answer the second research question: How do aspiring principals value the effect of immersive simulation on their content knowledge and ability to apply school law? Research participants were asked to describe their overall experience with immersive simulation. Nineteen codes were collapsed into four categories regarding participant’s overall experience. These were analysed for commonalities with three themes emerging from data analysis (Table 3). First, research participants strongly stated that immersive simulation supported adult learning needs. Second, they were clear in suggesting that the experience promoted increased legal knowledge and reasoning regardless of initial content knowledge. Third, they viewed this immersive simulation experience as an effective means by which to improve practice. These themes regarding overall experience are verified through myriad comments made by research participants throughout the open-ended survey. All research participants reported “real value” in involvement in the immersive simulation. Real value was represented throughout responses by words and phrases such as: “transferable” (participants:1, 3, 4, 7, 12 & 17), “insightful” (participants: 4, 5, 27 & 32), “engaging” (participants:5, 6, 9, 11,18, 23, 26 & 33), “authentic (participants: 22, 42 & 40),” “relevant” (participants:5, 10, 25, 31), “very effective” (participants:1, 4, 18, 26, 27, 35, 39 & 40), “powerful” (participants: 13, 39 & 44), “real-life” (participants:2, 15, 16, 28, 34, 35, 36, 39, 42 & 43) and “high value” (participants:8, 14 & 26). Regardless of the word used, however, research participants’ view of the experience of immersive simulation, as seen in the data, support the themes of immersive simulation as a powerful pedagogical tool to support adult learning, increase legal literacy and improve practice.

| Table 3 Themes for Research Question #2 |

||

| Themes of Overall Value of Immersive Simulation | ||

| Supports adult learning needs | Promotes increased legal knowledge and reasoning regardless of initial content knowledge. | Improves practice |

Adult Learning. Research participants unequivocally indicated that immersive simulation is an appropriate pedagogical tool to support adult learners. This theme is substantiated by comments such as the following: “This was absolutely wonderful!!” (Participant 22), “I learned a lot from the simulation” (participant 42) and “This was such an awesome experience!” (Participant 23). The position that immersive simulation is an appropriate pedagogical tool for adults was further supported by comments that expressed a ready desire to do more. For example, in the survey and per field notes from every session, several comments mirrored the following sentiments: “I would require this in class” (participant 10) and “I would love to do more simulations in the future” (participant 11). Research participants also expressed that the experience provided a great environment for their learning needs because of the responsiveness of the immersive simulation experience. Many made statements similar to those made by participants 33 and 24, respectively, who stated, [this is] “extremely engaging... and required me to think quickly and accurately,” and this was “very helpful in understanding legal situations. [I] would highly recommend such activity.” Analysis of these data strongly supported scholars’ positions on the potential power of immersive simulation as a pedagogical tool in higher education.

Increased Legal Literacy. Several participants expressed that they had learned a significant amount in a short period. Participant 12 stated “I am beyond blown away with how much I learned from the simulation!” while participant 44 suggested, “I learned more in the 2 hours I was here, than I have in my 3.5 years of teaching.” Quantitative data supported these perceptions of significant learning. In addition, this learning was specifically reported in relation to participants’ understanding of school law knowledge and their perceived ability to apply it–legal literacy. As participant 14 stated, “I was forced to have a conversation using facts and it helped me to retain the laws learned for future application.” Other comments related to legal literacy and reasoning can be seen in remarks such as: “[This was v]ery important as it helped me understand the situation and how to apply the laws better” (participant 31), “[It] was effective and allowed me to think more critically” (participant 26), “I learned a lot about school law and its application through the immersive simulations and collaborating with my peers”(participant 13) and “[This was an a]wesome strategy to assist with clarification of the law(s) and a chance to put them into practice” (participant 22). Equally important to the gains in legal literacy when using immersive simulation, were indications that given the experience, participants would retain their learning due to the near-transfer of knowledge in an authentic learning experience. This can be seen in the following comment by participant 38, “It was very educational and I will absolutely remember this information.” Several echoed this sentiment highlighting the overall value of the experience by making the claim that immersive simulation was a very effective tool by which to learn.

Improved practice. Based on research participants’ perceptions that the experiences increased their legal literacy, they further indicated that the manner in which they had learned would support a transfer skills and knowledge to the workplace. In this regard, participants explicitly commented on their increased understanding and awareness of the application of legal principles. For example, participant 4 stated, “The interaction prepared me to think deeply about the laws regarding students’ rights to freedom of speech.” These types of revelations were followed by comments of how immersive simulation would help them to be better leaders. Participant 16 suggested, “I really enjoyed it. I think that it can help administrators and future administrators learn the process of dealing with difficult situations.” The many comments following this line of thinking suggest that increased ability to apply a more critical and reflective lens around the law would support principals’ practice as an administrator. This idea is perhaps summed up best by participant 12 who stated, “I think EVERY student in a leadership program should have ample opportunities to participate in the simulation. I know administrators would benefit from the practice.” Two others, participants 5 and 26 respectively, stated, “I loved the ability to actually be involved with a simulation. I think that this process was advantageous since I have the ability to practice these actual issues that I currently see in my school environment,” and “I think the experience provided me with an opportunity to address a really difficult situation. I was surprised at how realistic the situation was. I enjoyed it and I wished that I would have additional opportunities to engage in this kind of activity.” These comments highlight the realities of challenging situations that are routinely faced by administrators and the desire for opportunities to continue to build and hone skills. Participants highly valued their experiences in a risk-free environment as they could focus on the transfer of knowledge to skills pertinent to being successful as 21st century principals. Furthermore, immersive simulation was seen as a tool that could be used by administrators to improve the practice of their teachers. For example, participant 29 stated, “I wish I had this at my school to help my staff grow. It was great. I would definitely be interested in participating again.” The combination of these data suggests that immersive simulation was viewed as a revolutionary tool to improve practice in a variety of settings and capacities.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate the assertion that immersive simulation might be a valued pedagogical tool in preparing educational leaders, specifically in the realm of school law. Previous findings present efficacy of immersive simulation in enhancing preparation of pre-service teachers (e.g. Evans, 2013; Dieker, Hynes, Stapleton & Hughes, 2007; Mehlig & Shumow, 2013), but there is a gap in the literature on its efficacy in preparing educational leaders. My findings address this gap and show (a) immersive simulation can be used to increase school law content knowledge; and (b) the value of immersive simulation in adult learning was reported to promote perceptions of increased legal literacy regardless of initial content knowledge and improve practice. It was also viewed as an appropriate and effective tool for adult learning.

The first research question addressed whether participation in immersive simulation designed on tenets of situated learning theory and critical pedagogy would change aspiring principals’ overall knowledge of school law. A significant increase in knowledge was observed in each high-rate litigation areas. This finding supports the literature that indicates immersive simulation is a strong pedagogical tool for reinforcing knowledge in a variety of content areas and supports the “near transfer” of knowledge to skills (Johnson et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Dede, 2009). The largest gains made by participants were in the area of legal knowledge pertaining to the separation of church and state, followed by student rights and then employee rights. Initially, participants scored the lowest on the separation of church and state portion of the pre-test, making the biggest gains seen in the area about which educational leaders appeared to know the least. This may mean that participation in immersive simulation has the greatest impact in realms where educational leaders struggle the most. Because participants of this study were located in the south-eastern Bible belt region of the United States, many practices regarding the separation of church and state are more rooted in dominant culture and the status quo than in school law. To adeptly navigate these types of challenges, principals must possess strong knowledge of school law and be skilled in application of it (Bateman & Bateman, 2015; Davis et al., 2005; Pauken, 2012), enabling them to adroitly avoid litigation prominent in today’s culture (Gary, 2015). Given the social context in which these data were gathered this exposure may be effective in dissuading participants of entrenched beliefs and practices. Leveraging this type legal literacy in challenging the status quo also is shown to support efforts of large-magnitude reform (Bateman & Bateman, 2015; Davis et al., 2005; Pauken, 2012), suggesting that immersive simulation could aid principals in school improvement efforts.

Given that two of the three immersive simulation scenarios had elements of separation of church and state woven into them, these findings additionally suggest that repeated exposure to a concept in immersive simulation might also be key to increasing overall impact on learning. This finding, therefore, suggests that immersive simulation could be a powerful tool in addressing regional idiosyncrasies in thinking among educational leaders. For example, in the southeast, many educational leaders struggle with proper application of legal concepts regarding the separation of church and state, because the status quo is often in conflict with these legal concepts. In California, however, educational leaders may struggle with proper application of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act because many parents are hyper-vigilant about what they believe a school should have to provide. Regardless of school law knowledge, leaders develop thinking reflective of the way in which their region approaches legal issues, sometimes, even if it the reasoning conflicts with the law. Immersive simulation may be a tool to help ensure flexibility in thinking (Aldrich, 2009; Dede, 2009 and therefore, mobility for educational leaders.

The second research question addressed how aspiring principals value the effect of immersive simulation as adult learners. The value of immersive simulation in adult learning was reported to promote increased legal knowledge and reasoning, regardless of initial content knowledge; improve practice; and was found to be an appropriate and effective tool for adult learning. Universities have struggled to provide training that adequately supports the necessary transfer of knowledge acquisition to skill development of aspiring principals (Levine, 2005; Murphy, 2003). Redesign of courses to include job-embedded leadership opportunities, intended to address this, have surfaced different challenges with lack of quality and rigor due to difficulties in oversight (Darling-Hammond et al., 2010; Ravitch, 2015). Including immersive simulation experiences in educational leadership programs attends to the transfer of theory to practice while controlling for quality and rigor. These findings support what Dede’s (2009) research calls for–a near transfer of skills through an opportunity of moving from the theoretical realm to the practical realm in very close proximity to knowledge acquisition – and reinforces previous assertions that emerging technologies, including immersive simulations, could prove to be powerful tools for addressing pedagogical challenges of adequately preparing aspiring principals for leading in the 21st century (e.g. Dede, 2009; Johnson et al., 2011; McGaghie et al., 2010). Furthermore, given that there was a mix of experience levels of the participants (0-3 years), immersive simulation is not only an appropriate modality for adult learners, it also adequately meets the needs of both pre- and in-service principals in promoting increased legal literacy.

Conclusion

Analysis of these results indicates that immersive simulation adds a layer of complexity and richness to traditional pedagogical methods as it provides an experience unparalleled to those provided in more traditional learning opportunities. Simulations in the traditional sense (use of role-playing or scenarios to present opportunities for students to evaluate and react to authentic problems) are a staple of teaching school law, both in face-to-face and online settings. In an effort to bring authenticity to these tasks, some professors overlay these scenario discussions with opportunities to role-play the event. Much like in immersive simulation scenarios, these traditional methods ask learners to deal with facts of the case, make in-the-moment decisions and react to the consequences of them. However, empirical data from this study suggest that immersive simulation provides a layer absent from these traditional pedagogical methods. Experiencing scenarios through immersive simulation allows for an interaction with avatars that, by their nature, support a suspension of disbelief hard to maintain in traditional role-plays and thereby effectively embody the human condition (emotionality, aspiration, conflict, etc.). Because the avatars are not classroom peers, the participant cannot predict what the response may be, providing a learning opportunity that is hard to distinguish from real-life consequential experiences, despite being offered in a risk-free environment. And, while these responses may be imagined in traditional pedagogical methods, the suspension of disbelief cultivated by immersive simulation provides experiences laden with truly authentic human emotion. No longer is the learner simply dealing with the facts of the case, she is dealing with the facts as seen through the complexities of the human condition. This complicates the learner’s responses to the scenario as it overlays the black and white of the problems as they often appear on paper or in role-plays. This is critical to the learning process and skill development of educational leaders because rarely are situations that confront them simply a matter of applying a policy to black and white situation. If they were, we would not need highly trained and skilled professionals to make decisions. This is particularly true in the case of principals’ application of school law. Immersive simulation experiences move the learner beyond the type of black and white, right and wrong type of decision-making experienced in tradition learning experiences, to the “it depends” type of critical thinking necessary to be an effective 21st century educational leader. And, when educational leaders switch from this type of right and wrong decision making, to critical thinking, it is then that they can transform school law knowledge to an effective tool in challenging the status quo and to a powerful fulcrum for leading large magnitude reform. Immersive simulation provides for this iterative and creative process that gives opportunities to educational leaders to understood school law through a critical thinking process.

Implications for Practice

Analysis across all findings led to two implications. First, use of immersive simulations in training educational leaders could expose them to a range of topics in a risk-free environment while bridging the theory to practice gap. Universities and other institutions that prepare educational leaders are charged with equipping them with critical thinking. To be successful in this endeavour, they are increasingly integrating and relying on a variety of technologies which afford more real-world experiences (Johnson et al., 2016). While research in this area is limited, exploring the use of immersive simulation to close this gap is promising (Aldrich, 2009; Storey & Cox, 2015; Gilbert, Voelkel & Johnson, 2017). More research is needed, however, to determine if these perceptions of improved practice bears out in the field. Second, the use of immersive simulation may be helpful in providing on-going professional development to those already in educational leadership positions. Early studies have suggested this type of professional development is effective for and desired by, sitting principals (Gilbert, 2017). Leveraging legal literacy, particularly to address structures, policies and practices that perpetuate unearned privilege requires principals to be abreast of changes and nuances in the law.

Limitations

Due to limited access to immersive technology and the time needed to complete a module in an immersive simulation, this study was limited to a small, purposive sample of participants at two previously described institutions (n=43) in Georgia. Limiting the study to small sample decreased generalizability and limited the ability to observe statistical significance. Further limiting generalizability, this sample is only representative of aspiring principals at a certain point in their study – those who were just entering an educational leadership program or recently new to a principal’s position; have recently completed coursework in school law; or who are or have been, involved in job-embedded, performance-based components of their programming.

Another factor to be considered is the design of this particular platform. Immersive simulation experiences are unique in that they are reactive to each individual’s actions and reactions. This is possible because this particular platform is not fully software driven; there is a human in the loop–a simulation specialist who plays the avatar. While this study revealed that the responsiveness of the immersive simulation to each participant was part of what made it a valuable pedagogical tool, to account for differences in the human simulation specialists (the avatars), the experience was standardized through the consistent use of a scenario planner indicating a “moderate behavioural level.” The simulation specialist was instructed to ask several questions and be persistent in arguing myriad legal angles in an effort to prevail in his/her perceived rights. This allowed the research participants to fully explore various legal realms of each scenario. All necessary legal arguments were provided to the simulation specialist prior to the scenarios. To further support a standardized experience, I completed two training sessions per scenario with the simulation specialist. Given these factors, the exact replication of any one simulation experience could be difficult without attention to the aforementioned factors.

Areas for Future Research

This study lays the groundwork for future and broader studies in the use of immersive simulations to prepare aspiring principals. Additional research could examine discrete factors such as geographic locations to determine if proximity to the Bible belt has an impact on changes in frequencies of correct answers in the subtest of separation of church and state, gender, type of previous training and current educational role to determine if they play significant role in the outcome of the research questions.

Future research is also indicated in how institutions choose to teach school law to future educational leaders. Of the participants who had taken a university course in school law, 37.2% rated their course as outstanding or very good and 27.9% assigning a rating of good or fair. There were no ratings of “less than adequate.” However, of those who had received school law training through the job-embedded experiences, there were no ratings of "outstanding." Twenty-three percent rated their experience as very good or good and 7% assigned a rating of fair or less than adequate. If research participants’ perceptions of how well they learn school law are valid, then preliminary results seem to indicate job-embedded training is perhaps not as effective as taking a course. Future research would be necessary to validate this finding.

References

- Aldrich, C. (2009). Virtual worlds, simulations and games for education a unifying view. Journal of Online Education, 5(5), 1-4.

- Anderson, J. (2014). Simulating the litigation experience: How mentoring law students in local cases can enrich training for the twenty-first century lawyer. The Review of Litigation, 33(4), 799-836.

- Badiee, F. & Kaufman, D. (2015). Design evaluation of a simulation for teacher education. Sage Open, 5(2), 1-10.

- Boyland, L.G., Lehman, L.E. & Sriver, S.K. (2015). How effective are Indiana’s new principals? Implications for preparation and practice. Journal of Leadership Education, 14(11), 72-91.

- Bradley, E.G. & Kendall, B. (2015). A review of computer simulations in teacher education. Educational Technology Systems, 43(1), 3-12.

- Brown, J. S., Collins, A. & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

- Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D., Orr. M.T. & Cohen, C. (2007). Preparing school leaders for a changing world: Lessons from exemplary leadership development programs. Stanford, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Meyerson, D.L., LaPointe, M. & Orr. M.T. (2010). Preparing school leaders for a changing world: Lessons from effective school leadership programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Davis, S., Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M. & Meyerson, D. (2005). School leadership study developing successful principals. Educational Leadership, 17(6), 1-32.

- Davis, S., Leon, R. & Fultz, M. (2013). How principals learn to lead: The comparative influence of on-the-job experiences, administrative credential programs and the ISLLC Standards in the development of leadership expertise among urban public school principals. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 8(1), 1-33.

- Dede, C. (2009). Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning [Online Magazine]. Science Mag, 323, 66-69.

- Dieker,L., Hynes, M., Stapleton, C. & Hughes, C. (2007). Virtual Classrooms STAR simulator building virtual environments for teacher training in effective classroom management. New Learning Technology SALT, 4, 1-22.

- Evans, R. (2013). Educating pre-service teachers for family, school and community engagement. Teaching Education, 24(2), 123-33.

- Farkas, S., Johnson, J., Duffett, A., Foleno, T. & Foley, P. (2001). Trying to stay ahead of the game: Superintendents and principals talk about school leadership. Washington, DC: Public Agenda.

- Gary, H. (2015). Has the threat of lawsuits changed our schools? Education World [Online magazine].

- Gilbert, K.A. (2017) Investigating the use and design of immersive simulation to improve self-efficacy for aspiring principals. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, 16, 127-169.

- Gilbert, K.A., Voelkel, R.H. & Johnson, C.W. (2017). The power of immersive simulations to increase self-efficacy in leading professional learning communities. Journal of Leadership Education. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Jensen, D. (2014). Churn the high cost of principal turnover [Online magazine].

- Johnson, L., Adams-Becker, S., Cummins, M., Estrada, V., Freeman, A. & Hall, C. (2016). NMC Horizon Report 2016 Higher Education Edition. Austin, Texas, The New Media Consortium.

- Johnson, L., Smith, R., Willis, H., Levine, A. & Haywood, K., (2011). The 2011 Horizon Report Higher Education Edition. Austin, TX, The New Media Consortium.

- Jorgensen, M.A. & Hoffmann, J. (2003). History of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB). (Person Report of Assessment History.)

- Leithwood, K., Louis, S.K., Anderson, S. & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation.

- Levine, A. (2005). Educating school leaders. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Mehlig, L.M. & Shumow, L. (2013). How is my child doing? Preparing pre-service teachers to engage parents through assessment. Teaching Education, 24(2), 181-194. doi:10.1080/10476210.2013.786892

- Mertler, C.A. & Vannatta, R.A. (2005). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing.

- Militello, M., Schimmel, D. & Eberwein, H.J. (2009). If they knew, they would change: How legal knowledge impacts principal’s practice. NASSP Bulletin, 93(1), 27-52. doi:10.1177/0192636509332691

- Oplatka, I. (2009). Learning the principal's future internal career experiences in a principal preparation program. International Journal of Educational Management, 23(2), 129-144.

- Painter, S.R. (2001). Improving the teaching of school law: A call for dialogue. Brigham Young University Education & Law Journal, 2001(1), 213-230.

- Pauken, P. (2012). Are you prepared to defend the decisions you’ve made? Reflective equilibrium, situational appreciation and the legal and moral decisions of school leaders. Journal of School Leadership, 22(2), 350-384.

- Storey, V.J. & Cox, T.D. (2015). Utilizing TeachLivETM to build educational leadership capacity: The development and application of virtual simulations. American Research Institute for Policy Development, 4(2), 41-49. doi:10.15640/jehd.v4n2a5

- Voelkel, R., Johnson, C. & Gilbert, K. (2016). Use of immersive simulations to enhance graduate student learning: implications for educational leadership programs. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 19(2), 1-7.

- Waters, T., Marzano, R.J. & McNulty, B. (2003). Balanced leadership: What 30 years of research tells us about the effect of leadership on student achievement. A Working Paper. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED481972).

- Wei, R.C., Darling-Hammond, L. & Adamson, F. (2010). Professional development in the United States: Trends and challenges. Dallas, TX National Staff Development Council.

- Yuen, S., Yaoyuneyong, G. & Johnson, E. (2011). Augmented reality: An overview and five directions for AR in education. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 4(1), 119-140.