Review Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 2

Influencer Marketing: Role of Paid Communication and Product Congruency

Smitha Siji, Rajagiri Business School, Kerala

Citation Information: Siji, S. (2025). Influencer marketing: role of paid communication and product congruency. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(2), 1-15.

Abstract

Though influencer marketing is gaining massive popularity as a marketing tool with the digital revolution that is seen all around, many facets of this strategy still need to be studied. This study attempts to learn more about how Instagram influencers influence their followers and how they may improve their relationships with them. The study was conducted among 260 followers of three Instagram influencers from the field of food, fashion and travelling. Questionnaires were mailed to 250 followers of these 3 popular Instagram influencers from different parts of India, and 260 usable responses were received. The results reveal that the influencer’s credibility is positively influenced by influencer-product congruity, whereas this negatively influences the perception of paid communication. The influencer's credibility and positive attitude foster positive behavioural responses from the followers. Marketing managers must ensure influencer-product congruity while choosing suitable product influencers. Influencers should carefully choose the products for endorsement.

Keywords

Influencer Marketing, Product Congruity, Paid Communication, Behavioural Intention, Influencer Credibility, Attitude.

JEL Article Classification

M31.

Introduction

Influencer marketing is gaining massive popularity as a marketing tool with the digital revolution that is seen all around (Kadekova & Holiencinov, 2018). In three years, from 2019 to 2021, the value of influencer marketing worldwide has more than doubled to $13.8 billion. Whereas, the expansion has been even more explosive in the South-east Asian region where the worth of influencer marketing industry is estimated to be worth $638 million in 2019. The figures are expected to quadruple by 2024 to $2.59 billion (Gross, impact.com). The individuals or groups who aggregate followers of their social media profiles are called social media influencers (De Jans et al 2018; Gross & Wangenheim 2018). Advertisers choose these influencers for sponsored advertising based on their social media engagement (Hughes, Swaminathan, & Brooks 2019). These sponsored posts or paid promotions have a clear advertising message and are uploaded on the influencer’s social media profile (De Veirman et al 2017). Social media influencers who work as brand ambassadors on social media can be christened as today’s opinion leaders (Fakhreddin & Foroudi, 2022; Sokolova & Kefi, 2020; Yerasani et al., 2019). Influencer marketing is a marketing method in which influencers assist brands in persuading customers (Ki et al., 2020; Djafarova & Bowes, 2021). Collaboration with influencers, on the other hand, would be pointless if they can’t influence. Influencers maintain their own social media images as part of their job to maximise the number of their engaged followers (Tafesse & Wood, 2021).

This study attempts to learn more about how Instagram influencers influence their followers and how they may improve their relationships with them. The followers’ intentions are intimately tied to their subsequent actions vis-a-vis the influencer such as their desire to follow/imitate/recommend the influencer to other users (Casalo ´ et al., 2020). For influencers also, it is important to please their followers and satisfy their expectations in terms of what the followers demand as the growth in their audience base depends on how they manage their image (Hu et al., 2020; Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019). As a result, as a fundamental part of the influencer marketing phenomena, this research focused on the characteristics that influence influencers' trustworthiness from the viewpoint of followers.

The influence of the digital revolution can be seen in all aspects of people’s lives. Every other activity which was done on offline mode now happens online, over the phone. For example, news and social media updates, purchasing groceries online, cab booking etc, happens through their smartphones. Prompts and alerts are forms of online advertisement and are considered as noise in the virtual world. The media landscape is also changing tremendously with the advent of over the top (OTT) platforms like Amazon Prime and Netflix. All this adds to the challenge faced by the marketer to get the ever-distracted consumer to notice the advertising content and brand message (Chopra et al., 2021). Poor recollection of advertisements (Talaverna, 2015), and usage of ad blocker tools (Dogtiev, 2016) adds to the marketer’s woes. It is in this context that marketers are realizing that brand stories have better chances at consumer engagement which can be done through social media presence. Marketers are realising that along with the official Instagram page, engaging with influencers might be more rewarding as these influencers are ‘everyday’ people and have a huge follower base (Chopra et al., 2021). Customers believe influencers have more credibility and knowledge and hence they are willing to abide by the recommendations of the influencers (Casalo et al., 2017a; Berger & Keller, 2016). However, it remains a challenge to identify the right influencer who would significantly influence the intended audience (Wong, 2014). The number of influencers on Instagram has increased exponentially (InfluencerMarketingHub, 2020). According to the blogger Taher (2019), more than 110 million Instagram users reside in the United States of America (USA), 66 million in Brazil, 64 million in India and 56 million in Indonesia. It is in this context that this topic becomes worthy of research. There’s a dearth of studies analysing the effect of influencers on various facets of buyer behaviour.

The study is being done to find the impact of paid communication and product congruency on influencer marketing. The study aims to determine the relationship amongst these variables and how influencer credibility and attitude towards the influencer affect follower’s tendency to follow, imitate and/or recommend the influencer.

The study aims to bring forth how influencers on Instagram may improve their engagement with their audience. Study was conducted among 260 followers of three Instagram influencers who have several followers.

Literature Review

Influencer marketing is a mode of communication in which influencers help firms persuade buyers (Ki et al., 2020; Djafarova & Bowes, 2021). Collaboration between brand and influencers is very common today (Tafesse & Wood, 2021; Ibáñez Sánchez et al, 2021). Previous researches have defined influencer marketing and the various aspects of using influencer marketing as a promotional tool. The influencer can be a celebrity or a commoner and the primary differentiation between traditional promotions and Instagram promotions is the collaborations between businesses and influencers (Geyser, 2021). Influencers who have a large follower base are classified as macro-influencers and those with smaller follower size are christened as micro-influencers (Voorveld 2019). However, Brewster & Lyu (2020) found that micro-influencers with lower follower sizes can maintain higher parasocial relationships and interactions. Though macro-influencers have higher public reach and exposure (De Veirman et al 2017), micro-influencers were also seen to be positively engaged with their followers (Marques et al 2021). This reinforces the significance and influence of all kinds of influencers in social media. Traditional celebrities generally are people from movies, sports, music etc however the social media activities of the influencers make them celebrities (Tafesse & Wood, 2021; Schouten et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2020). As per reports, 93% of current firms use influencer marketing (SocialPubli, 2019) and 66% of them intend to boost their budget for influencer marketing in the coming year (InfluencerMarketingHub, 2020). The annual revenue from the influencer sector is almost US$10 billion (InfluencerMarketingHub, 2020). It is crucial for influencers to retain and upgrade their expertise in the subjects as that is the reason for followers to follow them (De Veirman et al., 2017). Eventually it is seen that influencers develop deep emotional bonds with their followers which becomes the basis for setting up long-term relationships (Tafesse & Wood, 2021). Lemon & Verhoef, (2016) report that the relationship between influencers and followers can be considered as similar to that between firms and customers and this is in turn formed over a period of time by the various touchpoints that happen between the influencers and their followers. As followers continue to make judgements about the influencers based on basic click-based behaviours, the influencer's reputation is constantly evolving. As a result, every episode by the influencer becomes important as that would determine the intention of the followers to continue following their influencers (Casalo ´ et al., 2020). In this context, commercial collaborations become more crucial as the association between the influencer and brand may be short-term but the association between influencer and follower as well as the brand and the customer need to be long-term (Ibáñez Sánchez et al, 2021; Kim & Kim, 2021). Previous studies have examined various facets of influencer marketing but haven’t examined the relationship between the influencer and the follower. This study, thus, strives to fill this gap in existing literature by examining how the relationship between influencers and their followers can be strengthened. Previous research has primarily been concerned with followers' responses to the promoted product or brand. This study is designed to examine the followers' responses to the influencer. In terms of intent to follow, followers' intents are highly correlated with their future behaviour (follow, imitate, recommend) in relation to the influencer. Conick (2018) reports that influencers are seen to win more consumer trust compared to other online sources. Companies employed influencers to develop two-way marketing communication across digital platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, etc. in order to alter the perceptions of their online followers regarding specific businesses (Markethub, 2016). Almost all marketers now recognise the significance of establishing genuine relationships between influencers and consumers. In 2017, over 58 percent of companies had affiliations with approximately 25 influencers (Association of National Advertisers, 2018), indicating the preference of marketers to nurture intimate relationships between customers and influencers (Conick, 2018).

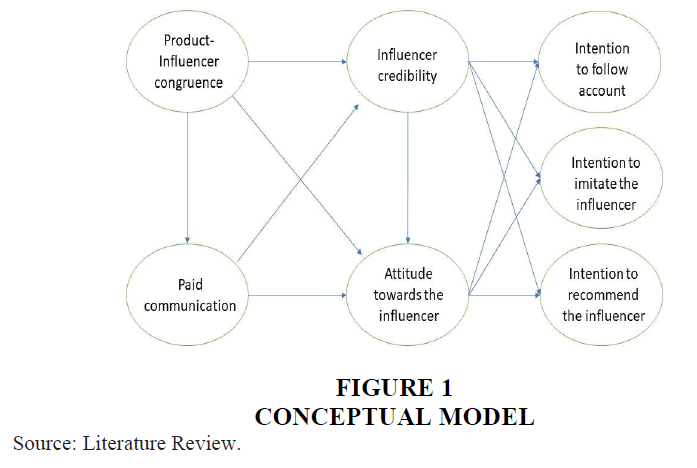

The theory of planned behaviour proposes that intentions to perform a behaviour can be strongly predicted by attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control (Azjen, 1991). This is the theoretical framework based on which the present study is being conducted. The behaviour in the context of this study is operationalised as intent to follow or imitate the influencer and/or to recommend the influencer to others (Algesheimer et al., 2005; Belanche et al., 2014; Casalo ´ et al., 2011; Casalo ´ et al., 2017b). Attitude is one of the strong antecedents of behaviour. A perusal of existing literature points out three important factors influencing attitude towards the influencer. The first among them is product-influencer congruence which means there has to be a fit between the influencer and the product promoted by the influencer (Kim & Kim, 2020). The second factor is influencer credibility. Only if the influencer is perceived as credible, the followers will have a positive attitude towards the influencer (Yoo & Jim, 2015). The third factor being considered is paid communication. The perception of the content being uploaded by the influencer to be paid promotion may form a negative attitude towards the influencer (Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019).

Influencers build up their market value by regularly uploading content and increasing their follower base (Lou & Yuan, 2019). They upload both sponsored and non-sponsored content. Sponsored content or paid promotion contains promotional messages about products and brands (Boerman et al 2017). There will be an integration of brands into the editorial content and the influencer is aptly compensated by the advertiser (Eisend et al. 2020; van Reijmersdal et al. 2020). The non-sponsored content is not particularly related to any specific company or brand (Tafesse & Wood, 2021). It is already known that there must be a fit between the product and the influencer to ensure the promotion is effective (Kim & Kim, 2021; Breves et al., 2019, Belanche et al, 2017). The followers may get surprised or confused if the influencer is seen diverting from the regular topics that they usually deal with (Stubb et al., 2019). Such instances may lead to the followers thinking that the influencer may be receiving material gains from the marketer and the campaign may be perceived as a sponsored program reducing the brand credibility (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020; Stubb et al., 2019; De Veirman et al., 2017). Thus the first hypothesis is framed as:

H1: Perceived influencer-product congruity negatively affects perceptions of paid communications.

Influencers on digital platforms have evolved into credible and reliable digital sources. (Freberg et al., 2011). The relationship between the source credibility and product fit was earlier examined in the context of celebrity endorsement (Mishra et al., 2015; Yoo & Jim, 2015; Park & Lin, 2020). The source's credibility increased whenever a high fit was found between the endorser and the promoted product (Yoo & Jim, 2015). Influencer-product congruity increases the influencer's credibility (Belanche et al, 2021). The credibility of the influencer largely depends upon the expertise and trustworthiness of the influencer (Schouten et al., 2021). Very early studies have reported that the absence of fit between the endorser and the product reduces the endorser’s credibility and leads to negative emotions towards th e endorser (Jacks & Cameron, 2003). Hence, influencers must maintain consistent content consistency (Breves et al., 2019; Casal´o et al., 2020). Thus the 2nd hypothesis is framed as:

H2: Perceived influencer-product congruity has a positive effect on the perception of the influencer’s credibility.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour by Azjen (1991) proposes attitude as one of the main antecedents of behavioural intentions. The attitude of the followers towards the influencers, thus, becomes important. The reason for following an influencer is generally the interest in the content shared by the influencer or the affinity towards the values and lifestyles propagated by the influencer (Sokolova & Perez, 2021). To maintain this interest, the influencer must choose brands that connect with the content of the influencer’s posts (Casalo ´ et al., 2020; Breves et al., 2019). This may help in maintaining a positive attitude towards the influencer. The inconsistency between the regular content uploaded by the influencer and the products being endorsed may affect the attitude of the followers towards the influencers (Stubb et al, 2019). The 3rd hypothesis is:

H3: Perceived influencer-product congruity has a positive effect on attitude of followers towards the influencer.

There are instances where influencers acknowledge that they are paid for the promotion e.g., “Sponsored” (Evans et al., 2017) and sometimes they do not (van Reijmersdal et al., 2020; Stubb & Colliander, 2019). If the influencer’s evaluation of the product is not sufficiently objective or the followers think that the influencer is paid because the content is biased, it may negatively affect the credibility of the influencer (Djafarova & Bowes, 2021; De Veirman & Hudders, 2020). When the influencer justified receiving compensation from the sponsor, it increased the credibility of the message and source compared to a simple disclosure about the sponsorship (Stubb et al., 2019). De Veirman and Hudders (2020) found that this leads to negative perception about the influencer’s credibility. Thus the 4th hypothesis is:

H4: Influencer’s post being perceived as a paid communication negatively affects the perception of the influencer’s credibility.

Using ad blockers, consumers avoid adverts as much as possible. In this situation, influencer marketing is believed to be less intrusive and more engaging than conventional web advertisements like pop-ups and banners. Additionally, marketers are utilising influencers to engage the segment of consumers that often skip or avoid commercials (Conick, 2018). In such a scenario, if the followers get to know that the content of the influencer is actually an ad, their attitude towards the influencer can worsen and even have detrimental effects when the credibility of the source is affected (Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019; Stubb et al., 2019; Evans et al., 2017). Thus, the 5th hypothesis is stated as:

H5: The influencer’s post being perceived as a paid communication has a negative effect on followers’ attitudes towards the influencer.

It is important for influencers to retain their followers and add new ones, as that is how they establish a huge community that forms the foundation of their influence (Hu et al., 2020; Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019). The growth of their follower base depends upon the credibility they have in the minds of the followers. When influencers maintain their credibility, it should favourably affect the attitude of followers towards them (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017). Along with promoting products or brands, the influencers must ensure that they are maintaining congruency with their usual content, as this will help in the continuance of their followers (Ki et al 2020). Hence, the 6th hypothesis is:

H6: The perceived credibility of an influencer has a positive effect on the followers’ attitude towards the influencer.

The behavioural response of the customers is very important for the marketers and credibility of the influencer is an important factor in shaping the behavioural response (Argyris et al., 2021; Sokolova & Kefi, 2020; Belanche et al., 2020; Schouten et al., 2021; Cosenza et al., 2015) The response expected from influencer marketing if the influencer is found credible, consists of continuing to follow the influencer, imitating the influencer, or recommending the influencer to others (Casalo ´ et al., 2020; Ki & Kim, 2019; Casalo ´et al., 2017b). Hence, if the customers are influenced by the influencer, they should be sharing the brand information endorsed by the influencer with their contacts. Its known from the Theory of Planned behaviour that attitude is an antecedent of behavioural response (Ajzen, 1991). Hence, the behavioural response to follow, imitate or recommend the influencer will also depend upon the attitude of the followers towards the influencer (Sokolova & Kefi, 2020; Ki & Kim, 2019). Thus the 7th & 8th hypothesis is:

H7: The perceived credibility of the Influencer mediates Product-Influencer congruence and intention to follow account.

H7a: The perceived credibility of the influencer has a positive effect on followers’ intention to continue following the influencer.

H7b: The perceived credibility of the influencer has a positive effect on followers’ intention to imitate the influencer.

H7c: The perceived credibility of the influencer has a positive effect on followers’ intention to recommend the influencer.

H8: Attitude towards the influencer mediates the relationship between Paid Communication and Intention to recommend the influencer.

H8a: The followers’ attitude towards the influencer has a positive effect on their intention to continue following the influencer.

H8b: The followers’ attitude towards the influencer has a positive effect on their intention to imitate the influencer.

H8c: The followers’ attitude towards the influencer has a positive effect on their intention to recommend the influencer.

Thus, based on the literature review, the study aims to test the research model given in Figure 1.

Research Methodology

The present study seeks to find out whether influencer-product congruence affect followers’ attitude towards the influencer. Will paid communications harm the credibility of the influencer? Does influencer marketing have an impact on followers? Do influencers’ promotional actions affect their credibility? A descriptive research design was used to conduct the study. A focus group discussion was carried out with marketing faculty and practising digital marketing experts. This group viewed the Instagram posts of several influencers. Three different influencers were selected from three different product categories (fashion, food and travelling). These three product categories happen to be the ones having the most influencers. The influencers were selected based on their follower strength. Questionnaires were mailed to the followers of these three well-known influencers. The followers belonged to the state of Kerala in India. Questionnaires were mailed to 250 followers of each influencer. However, only 260 usable responses were received. The data was collected between December 2021 and January 2022. The survey instrument was a questionnaire on the variables of the research model. The items were adopted from different sources and the details are provided in Table 1.

| Table 1 Source of Scale Items | |

| Variables | Source |

| Paid communication | De Veirman and Hudders, (2020) |

| Influencer-product congruence | Xu & Pratt, (2018), |

| Perceived credibility of the influencer | Müller et al., (2018); Ohanian (1990) |

| Attitude toward the influencer | Silvera & Austad, (2004) |

| Intention to follow the influencer’s account | Algesheimer et al., (2005); Belanche et al., (2014) |

| Intention to imitate the influencer | Casalo ´ et al., (2011) |

| Intention to recommend the influencer | Algesheimer et al., (2005); Casalo ´ et al., (2017b). |

On a 7-point scale, where 1 meant "strongly disagree" and 7 indicated "strongly agree," each item was measured. The sample consisted of 72% women and 28% men. 53% respondents were aged between 20 and 30 and 42% respondents were aged between 31 and 40. Hence, age-wise also it can be seen that the respondents belonged to the prime age category for the products selected for the study.

The Cronbach’s alpha values can be seen from Table 2. All the variables of this study are reliable, since their respective reliability coefficients exceed 0.70.

| Table 2 Reliability | |

| CONSTRUCTS | CRONBACH’S a |

| Product-Influencer Congruence | 0.729 |

| Paid Communication | 0.719 |

| Influencer Credibility | 0.795 |

| Attitude towards the influencer | 0.820 |

| Intention to follow | 0.756 |

| Intention to imitate | 0.788 |

| Intention to recommend | 0.779 |

From Table 3 it can be seen that discriminant validity is ensured as the square roots of the AVE (Average variance extracted) for each latent variable is higher than any other latent variables above, below, left or to its right.

| Table 3 Discriminant Validity | |||||||

| Product-Influencer Congruence | Paid Communication | Influencer Credibility | Attitude towards the influencer | Intention to follow account | Intention to imitate the influencer | Intention to recommend the influence | |

| Product-Influencer Congruence | -0.781 | 0.12 | 0.744 | 0.697 | 0.707 | 0.676 | 0.686 |

| Paid Communication | 0.12 | -0.802 | 0.069 | 0.1 | 0.084 | 0.143 | 0.225 |

| Influencer Credibility | 0.781 | 0.069 | -0.828 | 0.82 | 0.787 | 0.737 | 0.774 |

| Attitude towards the influencer | 0.697 | 0.1 | 0.82 | -0.834 | 0.806 | 0.619 | 0.734 |

| Intention to follow | 0.707 | 0.084 | 0.828 | 0.822 | -0.834 | 0.711 | 0.734 |

| Intention to imitate | 0.676 | 0.143 | 0.737 | 0.619 | 0.711 | -0.783 | 0.781 |

| Intention to recommend | 0.686 | 0.225 | 0.774 | 0.734 | 0.734 | 0.78 | -0.783 |

Convergent validity can be established only if the constructs are proven to be related in reality. This would establish whether answers from different individuals are correlated with latent variables.

From Table 4, it can be seen that the values for respective latent variables are 0.5 or above. Since the criteria for accepting convergent validity is satisfied, convergent validity is established for the scale.

| Table 4 Convergent Validity | |

| Constructs | AVE values |

| Product-Influencer Congruence | 0.553 |

| Paid Communication | 0.643 |

| Influencer Credibility | 0.619 |

| Attitude towards the influencer | 0.649 |

| Intention to follow | 0.675 |

| Intention to imitate | 0.611 |

| Intention to recommend | 0.608 |

The descriptive statistics are mentioned in Table 5. It can be seen that mean values range between 4.7 to 5.4 on a scale of 1 to 7. Hence most of the respondents agreed with the scale items.

| Table 5 Descriptive Statistics | ||||||

| Construct | Mean | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Skewness Statistic | Kurtosis Statistic |

| Product-Influencer Congruence 1 | 5.496 | 0.05857 | 2 | 7 | -1.00052 | 1.7135 |

| Product-Influencer Congruence 2 | 4.776 | 0.06664 | 2 | 7 | -0.05322 | -0.25236 |

| Product-Influencer Congruence 3 | 5.373 | 0.057 | 2 | 7 | -0.74861 | 0.96316 |

| Product-Influencer Congruence 4 | 4.876 | 0.06697 | 1 | 7 | -0.29035 | 0.11476 |

| Paid Communication 1 | 5.173 | 0.06485 | 2 | 7 | -0.71935 | 0.5414 |

| Paid Communication 2 | 4.715 | 0.07812 | 1 | 7 | -0.46555 | 0.15815 |

| Paid Communication 3 | 5.019 | 0.08146 | 1 | 7 | -1.02447 | 1.15343 |

| Influencer Credibility 1 | 5.173 | 0.06992 | 2 | 7 | -0.19898 | -0.55916 |

| Influencer Credibility 2 | 5.338 | 0.06677 | 2 | 7 | -0.46429 | -0.00629 |

| Influencer Credibility 3 | 5.180 | 0.06747 | 2 | 7 | -0.23803 | -0.36143 |

| Influencer Credibility 4 | 5.261 | 0.06542 | 2 | 7 | -0.46003 | -0.21521 |

| Attitude towards the influencer 1 | 5.261 | 0.06721 | 3 | 7 | 0.01423 | -0.83808 |

| Attitude towards the influencer 2 | 5.373 | 0.07009 | 2 | 7 | -0.43331 | 0.04976 |

| Attitude towards the influencer 3 | 5.338 | 0.06743 | 3 | 7 | -0.19675 | -0.54141 |

| Attitude towards the influencer 4 | 5.330 | 0.0658 | 2 | 7 | -0.30206 | -0.09081 |

| Intention to follow account 1 | 5.288 | 0.06843 | 3 | 7 | -0.26107 | -0.52503 |

| Intention to follow account 2 | 5.315 | 0.06519 | 2 | 7 | -0.45867 | 0.53701 |

| Intention to follow account 3 | 5.134 | 0.06566 | 3 | 7 | -0.09466 | -0.53465 |

| Intention to imitate the influencer 1 | 5.065 | 0.06538 | 1 | 7 | -0.45003 | 0.28171 |

| Intention to imitate the influencer 2 | 5.042 | 0.06523 | 1 | 7 | -0.46608 | 0.32104 |

| Intention to imitate the influencer 3 | 5.142 | 0.06211 | 1 | 7 | -0.54489 | 0.78954 |

| Intention to imitate the influencer 4 | 5.096 | 0.06125 | 2 | 7 | -0.38821 | -0.18546 |

| Intention to recommend the influence 1 | 5.242 | 0.06468 | 2 | 7 | -0.43727 | 0.15893 |

| Intention to recommend the influence 2 | 5.253 | 0.06486 | 2 | 7 | -0.42172 | 0.26648 |

| Intention to recommend the influence 3 | 5.253 | 0.06733 | 2 | 7 | -0.35492 | 0.09829 |

| Intention to recommend the influence 4 | 5.126 | 0.06458 | 2 | 7 | -0.58748 | 0.05861 |

Results

The model fit and quality indices are: Average path coefficient (APC)=0.382, P<0.001, Average R-squared (ARS)=0.554, P<0.001, Average adjusted R-squared (AARS)=0.551, P<0.001, Average block VIF (AVIF)=2.538, acceptable if <=5, ideally <=3.3, Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF)=3.594, acceptable if <=5, ideally <=3.3, Tenenhaus GoF (GoF)=0.587, small >=0.1, medium >=0.25, large >=0.36, Sympson’s paradox ratio (SPR)=0.917, acceptable if >0.7, ideally = 1, R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR)=0.991, acceptable if >=0.9, ideally = 1, Statistical suppression ratio (SSR)=1.000, acceptable if >=0.7, Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR)=0.917, acceptable if >=0.7.

It is evident that all the values are in the acceptable range.

Figure 2 depicts the structural model run using WARP PLS software. This application includes a graphical user interface for variance-based and factor-based structural equation modelling (SEM) employing the partial least squares and factor-based approaches. Figure 2 shows the beta values and P values also.

The beta values and p values of each of the hypothesis and the result whether the hypothesis is accepted or rejected can be seen in Table 6. H1 stated as perceived influencer-product congruity negatively affects perceptions of paid communications is accepted. H2 framed as perceived influencer-product congruity has a positive effect on the perception of the influencer’s credibility is also accepted. This relationship has the highest beta value as well hence reaffirming that influencer-product congruity and credibility are related. The 3rd hypothesis - perceived influencer-product congruity has a positive effect on attitude of followers towards the influencer is also accepted but the beta value is low which signifies that the strength of the relationship is weak. The 4th hypothesis stated as the influencer’s post being perceived as a paid communication negatively affects the perception of the influencer’s credibility is rejected. Future studies can explore this relationship to establish whether the perception of Paid Communication has an influence on the credibility of the influencer. H5 is stated as the influencer’s post being perceived as a paid communication has a negative effect on followers’ attitudes towards the influencer is accepted but the beta value is low. The 6th hypothesis which is framed as the perceived credibility of an influencer has a positive effect on the followers’ attitude towards the influencer is accepted and has a beta value of 0.66 which signifies the strength of this relationship. Thus, attitude and credibility are very strongly correlated. The 7a, 7b and 7c hypotheses that the perceived credibility of the influencer has a positive effect on followers’ intention to continue following, imitate and recommend is accepted. The 8a, 8b and 8c hypotheses that the followers’ attitude towards the influencer has a positive effect on their intention to continue following, imitate and recommend is also accepted. However, the test of mediation did not yield fruitful results and hence mediation could not be proved.

| Table 6 Hypotheses Testing Results | |||

| Hypothesis | Beta | P-Value | Results |

| H1 | 0.24 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H2 | 0.76 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H3 | 0.16 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H4 | 0.09 | =0.07 | Rejected |

| H5 | 0.16 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H6 | 0.66 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H7a | 0.42 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H7b | 0.58 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H7c | 0.48 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H8a | 0.48 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H8b | 0.20 | <0.01 | Accepted |

| H8c | 0.35 | <0.01 | Accepted |

Discussion and Implications

Based on the results obtained after the structural equation model was tested, the first three hypotheses were accepted. It means that influencer-product congruity and credibility are strongly correlated however, it negatively influences the perception of paid communication. Hence if the product and influencer is in congruence, the perception of paid communication will be subdued. The beta value of H3 is low which may mean that the attitude towards the influencer has been formed even before the influencer starts endorsing a specific brand and hence the influencer-product congruity is not a strong factor for the attitude towards the influencer. This result is in congruence with the Theory of Planned Behaviour, which proposes that attitude is a strong antecedent of behaviour. If the followers have a positive attitude towards the influencer, they will continue to demonstrate the behaviour in terms of following, imitating and recommending to others. H4 is not supported and probably future studies can explore this relationship further. It is important for marketers to ascertain the impact of the perception of ‘paid communication’ on the credibility of the influencer. If few more studies could test the relationship, a valid conclusion can be drawn. H5 is also accepted which means the perception of paid communication negatively affects the attitude towards the influencer. It can be inferred as when there is influencer-product congruity, credibility and positive attitude towards an influencer, then the perception of paid communication doesn’t seem to matter much. As influencer marketing is being used in a big way by marketers, customers now seem to be conditioned to the fact that brand promotions by influencers is an acceptable norm. According to the 6th hypothesis, credibility had a favourable effect on attitude towards the influencer and the beta value is also high. Marketers need to make a note of this finding. The influencer must be carefully chosen. The credibility of the influencer is very crucial and it should never be compromised. The hypotheses related to behavioural responses, H7 & H8 are also aptly supported. Thus, credibility and a positive attitude towards the influencers will create the desired behavioural response (to follow, imitate and recommend the influencer). The results of this study are in congruence with the findings of earlier studies done on the same area (De Veirman & Hudders, 2020; Casalo ´ et al., 2020; Ki et al., 2020; Jimenez-Castillo & Sanchez-Fern ´ andez, ´ 2019). Belanche et al (2021) conducted this study with one influencer in fashion & beauty segment. The present study extended it further by examining 3 different influencers from 3 different product categories related to fashion, food and travelling. The findings from this study imply that credibility, positive attitude and influencer-product congruity are very crucial when it comes to influencer marketing and this finding is in corroboration with earlier studies (Park & Lin, 2020; Yoo & Jim, 2015; Mishra et al., 2015). Thus, influencers need to ensure that the products that they are endorsing is in congruence with the contents that they post in their Instagram pages (Breves et al., 2019). If there is inconsistency between their usual content and their promotional content, followers may become suspicious and the influencer may be perceived as biased (De Veirman & Hudders, 2020). It has been found that customers believe negative reviews and it reduces their intention to purchase (Popy & Bappy, 2022) Gamage & Ashill (2023) report that if the content by the influencer has a commercial orientation, it reduces the trustworthiness of the content as well as the influencer. This will neither be in the interest of the influencer nor the marketer. Again, credibility and attitude have a bearing on the behavioural response in terms of following, imitating and recommending the influencer (Ki & Kim, 2019; Cosenza et al., 2015). However, credibility is more significant than attitude as attitude may have been formed from the time the followers start following the influencer. In contrast, credibility is seen once the influencer starts doing promotional content.

Influencer marketing is an innovative approach to traditional media's issues. Managers must ensure that the influencers they choose to promote their brands must have congruity. This implication applies to influencers as well. While deciding on which brands to endorse, they should also ascertain that the brand matches with the usual content done by the influencer. This will help further enhance the credibility and attitude towards the influencer and elicit positive responses in terms of following, imitating and recommending the influencers. This will lead to a mutually beneficial relationship for the influencer and the marketer.

The current research collected data from the followers of three different influencers from three different product categories: food, fashion and travelling. However, data was not categorised separately to compare the responses between the followers of the different influencers. Future studies can investigate whether the behavioural responses differ between the different product categories.

Conclusion

The study findings revealed that the influencer’s credibility and attitude towards the influencer has direct favourable effects on the responses of followers. In particular, the influencer's credibility and attitude greatly influenced behavioural intentions to emulate and endorse the influencer. The idea that the post of the influencer is actually a sponsored advertisement has no detrimental effect on followers' judgments of the credibility of the influencer. The fundamental explanation for this may be that followers continue to follow an influencer's posts because they find them entertaining and/or soothing; hence, in this case, they give less weight to the credibility factor of the influencer. When the total effects are looked upon, however, the perceived credibility of the influencer brings forth more favourable behavioural responses towards the influencer.

Statements and Declaration

• The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

• The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

• The author certifies that I have no affiliation with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

• The author has no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledges the help received from the PGDM student Merlin Shaji for data collection and analysis.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes.

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of marketing, 69(3), 19-34.

Argyris, Y. A., Muqaddam, A., & Miller, S. (2021). The effects of the visual presentation of an Influencer's Extroversion on perceived credibility and purchase intentions—moderated by personality matching with the audience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102347.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Flavián, C. (2014). The role of place identity in smart card adoption. Public Management Review, 16(8), 1205-1228.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., Flavián, M., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2021). Building influencers' credibility on Instagram: Effects on followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses toward the influencer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102585.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Belanche, D., Flavián, C., & Pérez-Rueda, A. (2017). Understanding interactive online advertising: Congruence and product involvement in highly and lowly arousing, skippable video ads. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 37(1), 75-88.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Belanche, D., Flavián, M., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Followers’ reactions to influencers’ Instagram posts. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 24(1), 37-54.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Berger, J., & Keller, F. (2016). Research shows Micro-Influencers have more impact than average consumers. Research Shows Micro Influencers Have More Impact than Average Consumers, 1(3).

Boerman, S. C., Willemsen, L. M., & Van Der Aa, E. P. (2017). “This post is sponsored” effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of Facebook. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38(1), 82-92.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Breves, P. L., Liebers, N., Abt, M., & Kunze, A. (2019). The perceived fit between instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: How influencer–brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research, 59(4), 440-454.

Brewster, M. L., & Lyu, J. (2020, December). Exploring the parasocial impact of nano, micro and macro influencers. In International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings (Vol. 77, No. 1). Iowa State University Digital Press.

Chopra, A., Avhad, V., & Jaju, A. S. (2021). Influencer marketing: An exploratory study to identify antecedents of consumer behavior of millennial. Business Perspectives and Research, 9(1), 77-91.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Conick, H. (2018). How to win friends and influence millions: The rules of influencer marketing. Marketing News, 52(7), 36-45.

Cosenza, T. R., Solomon, M. R., & Kwon, W. S. (2015). Credibility in the blogosphere: A study of measurement and influence of wine blogs as an information source. Journal of consumer behaviour, 14(2), 71-91.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

De Jans, S., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2018). How an advertising disclosure alerts young adolescents to sponsored vlogs: The moderating role of a peer-based advertising literacy intervention through an informational vlog. Journal of Advertising, 47(4), 309-325.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

De Veirman, M., & Hudders, L. (2020). Disclosing sponsored Instagram posts: the role of material connection with the brand and message-sidedness when disclosing covert advertising. International journal of advertising, 39(1), 94-130.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: the impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International journal of advertising, 36(5), 798-828.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dhanesh, G. S., & Duthler, G. (2019). Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness of paid endorsement. Public relations review, 45(3), 101765.

Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities' Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in human behavior, 68, 1-7.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dogtiev, A. (2016). Ad blockers popularity boom–Why is it happening.

Eisend, M., Van Reijmersdal, E. A., Boerman, S. C., & Tarrahi, F. (2020). A meta-analysis of the effects of disclosing sponsored content. Journal of Advertising, 49(3), 344-366.

Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of interactive advertising, 17(2), 138-149.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fakhreddin, F., & Foroudi, P. (2022). Instagram influencers: The role of opinion leadership in consumers’ purchase behavior. Journal of promotion management, 28(6), 795-825.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. A. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public relations review, 37(1), 90-92.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gamage, T. C., & Ashill, N. J. (2023). # Sponsored-influencer marketing: effects of the commercial orientation of influencer-created content on followers’ willingness to search for information. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 32(2), 316-329.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gross, J., & Wangenheim, F. V. (2018). The Big four of influencer marketing. a typology of influencers. Marketing Review St. Gallen, 2, 30-38.

Hu, L., Min, Q., Han, S., & Liu, Z. (2020). Understanding followers’ stickiness to digital influencers: The effect of psychological responses. International Journal of Information Management, 54, 102169.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of marketing, 83(5), 78-96.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ki, C. W. C., & Kim, Y. K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & marketing, 36(10), 905-922.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ki, C. W. C., Cuevas, L. M., Chong, S. M., & Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102133.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H. Y. (2021). Influencer advertising on social media: The multiple inference model on influencer-product congruence and sponsorship disclosure. Journal of Business Research, 130, 405-415.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of marketing, 80(6), 69-96.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of interactive advertising, 19(1), 58-73.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Marques, I. R., Casais, B., & Camilleri, M. A. (2021). The effect of macrocelebrity and microinfluencer endorsements on consumer–brand engagement in instagram. In Strategic corporate communication in the digital age (pp. 131-143). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mishra, A. S., Roy, S., & Bailey, A. A. (2015). Exploring brand personality–celebrity endorser personality congruence in celebrity endorsements in the Indian context. Psychology & Marketing, 32(12), 1158-1174.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Müller, L., Mattke, J., & Maier, C. (2018). # Sponsored# ad: exploring the effect of influencer marketing on purchase intention.

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers' perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of advertising, 19(3), 39-52.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Park, H. J., & Lin, L. M. (2020). The effects of match-ups on the consumer attitudes toward internet celebrities and their live streaming contents in the context of product endorsement. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 52, 101934.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Popy, N. N., & Bappy, T. A. (2022). Attitude toward social media reviews and restaurant visit intention: a Bangladeshi perspective. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 11(1), 20-44.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2021). Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: the role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. In Leveraged marketing communications (pp. 208-231). Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Silvera, D. H., & Austad, B. (2004). Factors predicting the effectiveness of celebrity endorsement advertisements. European Journal of marketing, 38(11/12), 1509-1526.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sokolova, K., & Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 53, 101742.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stubb, C., & Colliander, J. (2019). “This is not sponsored content”–The effects of impartiality disclosure and e-commerce landing pages on consumer responses to social media influencer posts. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 210-222.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stubb, C., Nyström, A. G., & Colliander, J. (2019). Influencer marketing: The impact of disclosing sponsorship compensation justification on sponsored content effectiveness. Journal of Communication Management, 23(2), 109-122.

Tafesse, W., & Wood, B. P. (2021). Followers' engagement with instagram influencers: The role of influencers’ content and engagement strategy. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 58, 102303.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Van Reijmersdal, E. A., Rozendaal, E., Hudders, L., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Cauberghe, V., & Van Berlo, Z. M. (2020). Effects of disclosing influencer marketing in videos: An eye tracking study among children in early adolescence. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 49(1), 94-106.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Voorveld, H. A. (2019). Brand communication in social media: A research agenda. Journal of advertising, 48(1), 14-26.

Wong, K. (2014). The explosive growth of influencer marketing and what it means for you. Diakses pada February, 16, 2018.

Xu, X., & Pratt, S. (2018). Social media influencers as endorsers to promote travel destinations: an application of self-congruence theory to the Chinese Generation Y. Journal of travel & tourism marketing, 35(7), 958-972.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yerasani, S., Appam, D., Sarma, M., & Tiwari, M. K. (2019). Estimation and maximization of user influence in social networks. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 44-51.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yoo, J. W., & Jin, Y. J. (2015). Reverse transfer effect of celebrity-product congruence on the celebrity's perceived credibility. Journal of Promotion Management, 21(6), 666-684.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 05-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15424; Editor assigned: 26-Nov-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-15424(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Dec-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-15424; Revised: 26-Dec-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15424(R); Published: 24-Jan-2025