Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 2

Indonesia SMES′ Internationalization Performance: The Roles of Institutional Context and Dynamic Capabilities

Apung Sumengkar, Universitas Indonesia

Lily Sudhartio, Universitas Indonesia

Setyo Hari W, Universitas Indonesia

Amiruddin Ahamat, Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka

Citation Information: Sumengkar, A., Kasali, R., Sudhartio, L., Hari, W.S., & Ahamat, A. (2023). Indonesia SMES' internationalization performance: The roles of institutional context and dynamic capabilities. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 26(2), 1-12.

Abstract

This study aims to assess the impact and interplay of Institutional Context, Dynamic Capabilities, both Owner Specific (Managerial) and Organizational Capabilities, and the performance of Indonesian exporting SMEs. We used quantitative techniques to collect data from the key analysis unit, which is Indonesia Small Medium Enterprises that are already exporting. We distributed structured questionnaires to more than 500 exporting Small Medium Enterprises from East Java, West Java, and Jakarta, Indonesia, and 135 SMEs responded. The important findings revealed that institutional environment, particularly government rules and network support, had a considerable impact on dynamic capacities. It has also been scientifically proved that the owner's ability to plan well and manage risk is critical in establishing dynamic organisational capabilities. Finally, the business performance of exporting SMEs has been shown to be directly influenced by institutional framework and intermediated by organisational dynamic capacities.

Keywords

Institutional Context, Government Regulation, Dynamic Capabilities, Entrepreneurial Orientation, International Entrepreneurship.

Introduction

Prior to the globalization era, the world's companies and marketplaces were divided into two categories: major (multinational) companies that focused on worldwide/regional markets and small medium enterprises (SMEs) that competed only on the home market (Etemad, 2004). However, the advancement of information technology (particularly the internet) has removed the barrier dividing foreign and domestic markets, allowing major (multinational) corporations and small businesses to compete in the same international arena (Levitt, 1983; Fraser & Oppenheim, 1997). SMEs can no longer hide behind government protection of their native market (Etemad, 2004; Fraser & Oppenheim, 1997; Levitt, 1983), requiring them to compete directly with huge (multinational) corporations not only in their home country, but also in other nations. We are interested in doing research on the impact of institutional environment and dynamic capacities on the performance of exporting SMEs in Indonesia, given the importance of internationalization of SMEs to ASEAN nations.

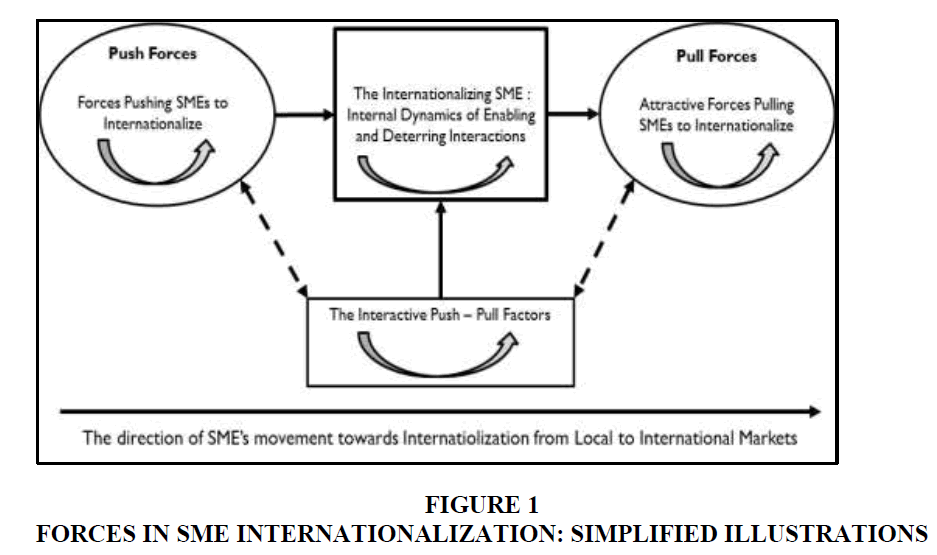

International Entrepreneurship

Johnson defined entrepreneurship as "the process of creating or seizing an opportunity and pursuing it regardless of the resources currently controlled," echoing Timmons et al. (2004) definition of entrepreneurship as "the process of creating or seizing an opportunity and pursuing it regardless of the resources currently controlled". Meanwhile, some important experts, such as Covin & Sleven (1989), appear to be combining entrepreneurship into three (3) major dimensions: invention, proactive conduct, and risk-taking action. Taking into account the aforementioned evolution, McDougall & Oviatt (1997) described international entrepreneurship as a “combination of inventive, proactive, and risk-seeking behaviour that crosses national borders and is meant to create value in organisations”. As a result, most studies of international entrepreneurship focus on essential entrepreneurial behaviours and comparisons of those behaviours across countries. Etemad (2004) created a comprehensive, yet easy framework for understanding the different fundamental elements that influence international entrepreneurship. The framework (Figure 1) comprised of three (three) important components that are thought to have an impact on SMEs' internationalisation.

The “Pushing Forces of Internationalization” the “Attractive Pulling Incentives of Internationalization and the “Mediating Forces of Internationalization” are the three (three) major components of Etemad's paradigm. The three (three) elements are thought to push, pull, and interact with SME's foreign business activity. The firm's perspective on (a) the external situation, (b) the firm's competitive landscape, (c) internal competencies related to the external environment requirements, (d) the impact of external forces on the firm's available strategic options, and (e) the feasibility of strategy formulation and implementation moderate the interaction of these 3 (three) forces.

Institutional Context

Institutions are defined by North (1990) as "the humanly constructed limitations that structure human interaction". Similarly, Scott (1995) described institutions as "regulative, normative, and cognitive structures and activities that provide social behaviour with stability and meaning". We can deduce institutions as formal and informal ways of doing things in the realms of politics (such as bribery, transparency), law (e.g., free commerce, controlling administration), and society by combining the two arguments (e.g., business ethics, entrepreneurial orientation). Many academics have identified a country's political environment as a major source of political risk (Butler & Joaquin, 1998; Kobrin, 1981; Nigh, 1985).

In light of this, international business research has developed a stronger link between institutional background/context and organisations, resulting in a new stream of research known as institution-based view, which focuses on the dynamic interface between institutions and organisations, treats institutions as independent variables, and considers key strategic decisions as the primary output (Peng, 2003). Key strategic decisions are driven not just by industry trends and corporate competencies, but also by the formal and informal environment in which the business and management team operates (Bruton et al., 2007; Carney, 2005; Lee et al., 2007; Lu & Yao, 2006; Meyer & Nguyen, 2005; Teegen et al., 2004; Wan, 2005; Zhou et al., 2006). To put it another way, institutional backdrop encompasses more than just the setting.

Instead, institutional background can have a big impact on a company's ability to create and execute essential initiatives, which can ultimately lead to a competitive advantage (Ingram & Silverman, 2002). A claim supported by key research on political strategies (Clougherty, 2005), the character of nation-states influencing key strategic initiatives on change and innovation (Lewin & Kim, 2004), and the impact that institutional background can have on a company's decision to diversify (Ring et al., 2005; Peng et al., 2005; Wan, 2005).

Dynamic Capabilities

One of the key drivers of durable competitive advantage, according to Barney (1991), is firm internal resources. In line with this viewpoint, Teece (2007) suggested that in a rapidly evolving global ecosystem defined by important geographical dispersion and a diversified network of innovation and manufacturing, organisations must possess critical capabilities, competencies, and assets that are difficult to duplicate. These important capabilities, competencies, and assets should be able to be generated, extended, enhanced, protected, and relevant to the company's current competitive landscape and critical issues on a constant basis.

Organization Dynamic Capabilities

Dynamic capabilities, according to Teece (2007), are “the company's ability to (1) sense and shape opportunities and threats, (2) seize key opportunities, and (3) maintain competitiveness by enhancing, combining, protecting, and, as necessary, reconfiguring the company's intangible and tangible competences and assets”. Teece (2007) further suggested that having these talents is particularly important for multinational corporations that compete in a highly competitive or international business environment with specific critical characteristics.

Owner Specific Dynamic Capabilities

Castanias & Helfat (1991) stressed the importance of cognitive capacity and talents, particularly among top executives. In a similar vein, Adner & Helfat (2003) stated that senior managers may have "dynamic managerial competencies" that include "building, integrating, reconfiguring, and competitively repositioning organizational resources and capacities". Bertrand & Schoar (2003) observed a significant impact of numerous top managers on the company's performance, which supports this argument. Managerial capacity and capacities were critical variables in making decisions on corporate action, cost-cutting measures, R&D expenditure, diversification, and mergers and acquisitions, all of which are important activities that might lead to strategic change.

We also discovered other research that claimed that CEO attributes (such as age, tenure, and level of education) are decisive variables in major firm transformations (Datta et al., 2003). Holbrook et al. (2000) also discovered that strategic decisions made by the senior management team in the early years of the semiconductor sector produced significant disparities in business results between large players. Rosenbloom (2000), for example, found that top management's attitudes to critical change at NCR, particularly the CEO's, changed dramatically over time. Due to the lethargy of their top management, NCR initially had a poor performance. When a new CEO, with a different viewpoint and experience than the previous one, was appointed to run the company, he proved to be instrumental in NCR's late but successful entry into the computing business.

Adner & Helfat (2003), on the other hand, contend that top management effects might be beneficial or bad, with varying consequences. However, because of differences in managerial cognitive capacity and talents, the paybacks given by particular dynamic capabilities are likely to be variable among important managers who possess these capabilities. Several studies have demonstrated increased empirical support for top management's impact on corporate outcomes. For example, Quigley & Hambrick (1950) discovered that the CEO has a significant impact on business performance variance, which grew from 12.7 percent on average between 1950 and 1969 to 25 percent on average between 1990 and 2009. Although the previous study showed that the CEO has a significant impact on the variation of business results, there has been little research on the relationship between institutional support, firm dynamic capabilities, owner particular dynamic capabilities, and firm performance. To better understand this issue, we began this research to look at the impact of institutional support, firm dynamic capabilities, and owner particular dynamic capabilities on Indonesian SMEs' internationalisation performance.

Key Hypotheses

H1 Institutional Context (IC) positively affects Owner Specific Dynamic Capabilities (OSDC).

Institutions matter and strategy scholars are increasingly recognizing this and factoring it into their study. According to Martin (2014), institutions can provide firms with more than just generic or comparative advantage; they can also be a source of competitive advantage, and firms with institutional competitive advantage can create idiosyncratic resources through interaction with their institutional environment. Home country institutions, for example, may provide enterprises with exclusive access to location-based resources such as financial, human, and social capital that are essential for internationalisation (Dunning, 2015; Xu & Meyer, 2013). Firms can internalize domestic environment benefits and turn them into firm-based ownership advantages (Hymer, 1960). Although location-based, such advantages might also result in firm-specific institutional advantages. Firms can use such benefits to compensate for their shortcomings as foreigners in new international marketplaces (Dunning, 2015; Hymer, 1960; Zaheer, 1995).

Institutional context, according to Ingram & Silverman (2002), can be formed by public or private entities in a centralized or decentralized manner, and can contain a wide range of organisations and procedures that enable transactions (Dhanaraj & Khanna, 2011). Countries' institutional frameworks, which consist of a combination of their political, community, and regulatory structures that form the foundation for trade and industry, vary in composition and quality (Robinson & Acemoglu, 2012; Davis & North, 2011). For example, a country's research and educational condition, as well as the availability of a financing medium and a well-trained workforce, all influence how innovation and entrepreneurship arise (Bartholomew, 1997; Bowen & De Clercq, 2008; Busenitz et al., 2000; Nelson, 1996).

H2 Institutional Context (IC) positively affects Organization Dynamic Capabilities (DC).

Li stated in 2013 that institutional context has an impact on how international entrepreneurship is shaped. The institutional framework will influence three (three) aspects of entrepreneurs' thinking: how they see business possibilities, what qualities (internal competencies) they possess, and the strategic decisions they make. Li (2013) identified three types of internationalisation strategy archetypes used by new businesses coming from emerging markets: (1) network-based strategies emphasizing the entrepreneurs' network, such as personal ties and the company's inter-organizational relationships with other parties; (2) price or volumebased strategies emphasizing the company's ability to compete on price and (3) price or volumebased strategies emphasising the company's ability to compete on price (Barney, 1991).

If we look at it more closely, the three (three) factors that Li was emphasising in the internationalisation process align with Teece (2007) three building blocks of dynamic capabilities, which are sensing (capabilities to sense, filter, shape, and calibrate business opportunities), seizing (structure, procedures, design, and incentive to seize the opportunities), and reconfiguring (structure, procedures, design, and incentive to reconfigure the opportunities) (configure alignment and realignment of specific tangible and intangible assets). The key argument of this study's hypothesis is that institutional environment has an impact on company dynamic capacities.

H3 Owner Specific Dynamic Capabilities (OSDC) positively affects Organization Dynamic Capabilities (DC).

Several scholars claimed that dynamic capacities existed at the person, firm, and network levels, with dynamic interaction occurring in the middle (Carlos, 2011; MacLean et al., 2015; Rothaermel & Hess 2007). Previous study has proven that individual and company qualities are inextricably linked (Felicio et al., 2015; Fernandez-Mesa & Alegre, 2015). Fisher (2012) claims that in competitive marketplaces such as international trade, when the target consumer can only be clearly defined, the entrepreneurs' goal becomes changeable.

In this situation, entrepreneurs should shift their focus away from achieving their business goals and toward maximising control of internal assets and resources such as knowledge, capability, skills, and social relationships; a process that can lead to new breakthroughs in all areas and is known as "effectuation" (Kalinic et al., 2014). This circumstance forces entrepreneurs, particularly in international economic activities, to rely more on their internal skills than on rational goal-setting and decision-making processes. As a result, evaluating organisational dynamic capabilities while disregarding entrepreneur capabilities is impracticable in the context of SME (Mudalige et al., 2019). Entrepreneur dynamic talents play a significant role in producing organizational-level dynamic capabilities, according to the study and thesis presented above.

H4 Organization Dynamic Capabilities (DC) positively affects Performance of Exporting SMEs (PER).

Dynamic capabilities, according to Eisenhardt & Martin (2000), are the company's main processes and activities that leverage important assets and resources-such as the integration, reconfiguration, gaining, and releasing process-to match and even drive strategic change in the market. Teece et al. (1997), in support of Eisenhardt and Martin, argued that dynamic capabilities are made up of three (three) clusters of key processes and activities carried out by key managers: (1) opportunity identification and assessment in the domestic and foreign markets, (2) resource mobilisation to seize key opportunities and capture value creations, and (3) continuous renewal of current capabilities (reconfiguration). Sensing is the most entrepreneurial of the three competencies, whereas seizing is more driven by basic managerial activities and concerns.

Borch and Madsen conducted an empirical study in 2007 to determine the impact of five (five) dynamic capabilities, namely (1) internal flexibility, (2) external reconfiguration/integration, (3) resource acquisition, (4) learning network, and (5) strategic path aligning capabilities, on innovative strategies, which were defined as proactive-creative and risktaking behaviour with a growth-oriented mind-set. Except for the relationship between strategic path aligning capabilities and SMEs, their research found a beneficial impact of dynamic capabilities on innovative (entrepreneurial) strategies.

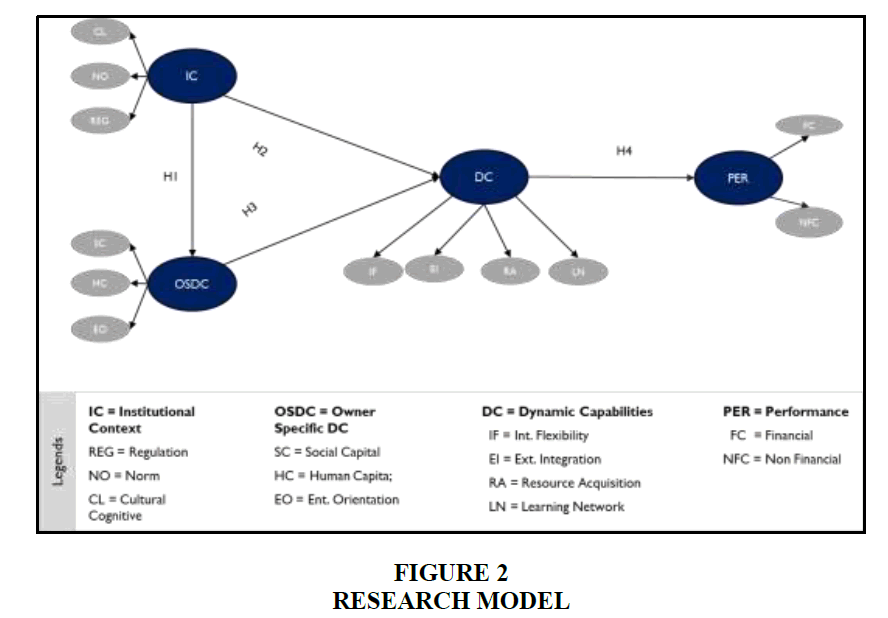

Internationalization is an entrepreneurial endeavour in and of itself, as it involves activities to protect growth potential by expanding to markets outside of the firm's native country. Internationalization is a dangerous move for SMEs, especially those with little resources to deal with serious commercial issues. Internationalization presents a firm with not only market obstacles, but also political, legal, and cultural ones, requiring it to adapt many of its business practises (McDougall & Oviatt, 1997). Al-Aali & Teece (2014) also suggested that successful internationalisation projects require the presence of certain critical criteria. The ability of the entrepreneur to identify key opportunities in the target international market, as well as the understanding of the suitability of the firm's product and/or service, as well as the calculation of the pre-work that needs to be done to educate potential new customers from the target international market, are the first two factors (Table 1 & Figure 2).

| Table 1 Key Hypothesis |

| Research Hypotheses |

| H1: Institutional Context (IC) positively affects Owner Specific Dynamic Capability (OSDC) |

| H2: Institutional Context (IC)positively affects Dynamic Capabilities (DC) |

| H3: Owner Specific Dynamic Capability (OSDC) positively affects Dynamic Capabilities (DC) |

| H4: Institutional Context (IC) positively affects Performance (PER) |

Research Methodology

The dynamic capacities questions were developed by Bolton & Lane (2012); Mudalige et al. (2019), Teece et al. (1997), and Teece (2007), while the institutional background questions were developed by Busenitz et al. (2000). After that, we ran a pre-test to validate the model's reliability and validity for each of the questionnaire's item indicators. As a result, we improved the questionnaire content before conducting the survey according to the agreed-upon technique. More than 500 exporting Small Medium Enterprises from East Java, West Java, and Jakarta, Indonesia, received the questionnaire, with 135 responding. We found 128 questionnaires from 128 SMEs after revising the questionnaire to ensure data completeness. The final data analysis was collected and processed with SPSS 23 and Lisrel 8.8 in two steps: analysis to evaluate the measurement model and structural model (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

Measurement Model Analysis

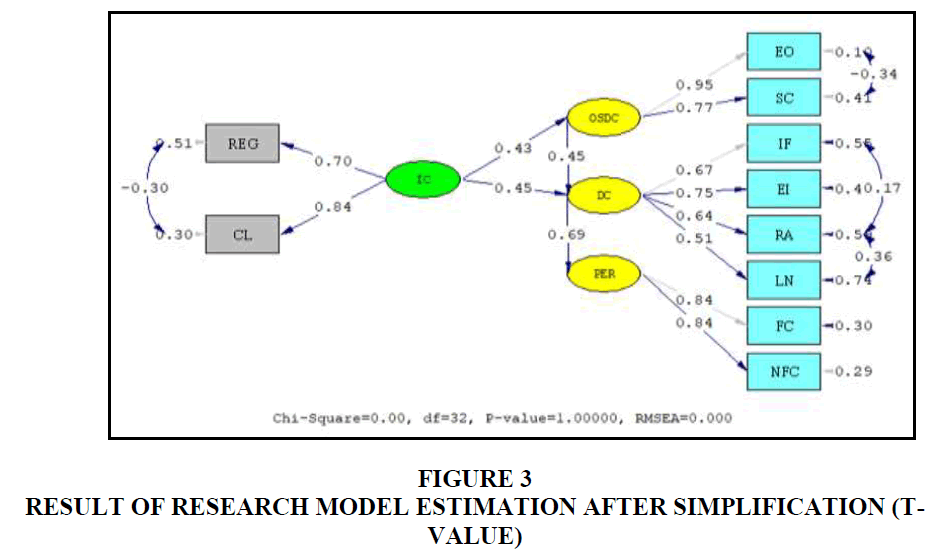

The measurement model analysis began with the measurement of each dimension (1st Order CFA), then the dimension's LVS calculation, and finally the measurement model analysis of the study variables using LVS indicators of the relevant dimensions (Hair et al., 2013; Wijanto, 2015). Human Capital in Owner Specific Dynamic Capabilities and Norms in Institutional Context are two latent variables that are not valid and should be deleted to assure model validity. As a result, Figure 3 shows the completed research model along with its t value.

Structural Model Analysis

The structural and measurement models have a strong fit, as evidenced by the GOFI score and significance test for each latent variable, making the overall research model of this study legitimate and good. The significance test in Table 2 shows that all four (four) important hypotheses are accepted; the four latent variables have positive correlations.

| Table 2 Result of Statistical Test of Research Model | ||||

| Hypotheses | t-Value* | Coefficient | Significant | Conclusions |

| H1: IC → (+) OSDC | 4,91 | 0,43 | Positive Significant | H1 supported |

| H2: IC → (+) DC | 3,54 | 0,36 | Positive Significant | H2 supported |

| H3: OSDC → (+) DC | 4,39 | 0,42 | Positive Significant | H3 supported |

| H4: DC → (+) PER | 0,67 | 0,36 | Positive Significant | H4 supported |

| GOFI : RMSEA (≤0,08**) = 0,00; NNFI (≥0,90**) = 1,06; CFI (≥0,90**) = 1,00 IFI (≥0,90**) = 1,04; SRMR(≤0,05**) = 0,05; GFI(≥0,90**) = 0,94; Norm χ2 (≤ 2) = 0,00 |

||||

Discussion

The findings of an empirical study of 128 exporting SMEs in Indonesia revealed that institutional environment influenced both owner specific dynamic capabilities (OSDC) and organisational dynamic capabilities considerably (DC). The findings support Landau et al. (2016)'s hypothesis that institutional context enhances a firm's competitive advantage from both a micro (managers) and an organisational perspective. It also backs up results from previous researchers that institutional support shapes corporate strategy and performance in emerging nations like Indonesia, which frequently have less mature SMEs than industrialized economies (Hoskisson et al., 2000; Wright et al., 2005). Furthermore, Crespo et al. (2022) contend that three business capabilities (entrepreneurial orientation, foreign market knowledge, and absorptive capacity) have a considerable impact on the level of entrepreneurial alertness, which has an impact on the company's international performance. Their research shows that the ability to detect and capture specific international business opportunities is critical to encouraging higher success in international new ventures (INVs). Entrepreneurial awareness, on the other hand, was rated as a capability shared by the management team and dispersed by the firm rather than as an individual assessment. This is consistent with earlier theoretical considerations in the literature (Rezvani et al., 2019; Sharma, 2018).

Our findings support Adner & Helfat (2003) findings that some managers may possess certain "dynamic managerial capabilities" with which to build, integrate, reconfigure, and competitively reposition organisational resources and capabilities. Our findings further support recent research by Mudalige et al. (2019), which found a strong link between owner-specific dynamic capabilities and organisation dynamic capabilities and internationalisation performance. Our findings also revealed that an organization's dynamic capabilities have a substantial impact on the performance of exporting SMEs in Indonesia, which supports Al-Aali & Teece (2014) claim that dynamic capabilities are critical for successful internationalisation. This further extends to the recent study by Chidlow et al. (2021) given that institutional forces not only shape organizational behavior but also affect emerging economy multinational enterprises’ (EMNEs’) internationalization strategies and organizational outcomes.

Conclusion

The construction of an empirical model that can be utilized to explain the dynamic interaction between institutional environment/background and dynamic capabilities to the performance of exporting SMEs in Indonesia is one of our research's main achievements. Our research found that the institutional backdrop, particularly government laws, has a substantial impact on the dynamic capabilities of exporting SMEs, both for individual owners and for the entire company. The cognitive ability of the exporting SME has a significant impact on the dynamic capabilities of the exporting SME (e.g. knowledge on how to monitor key risks in their business such as production cost, competitor movement, et al). Our findings also revealed that firm-wide dynamic capabilities are important mediators between owner-specific dynamic skills and business performance, implying that individual knowledge and experience may not be important elements for the success of exporting SMEs in Indonesia. Argument that runs counter to popular belief that the success of SMEs exporting is completely dependent on their owners' ability.

References

Adner, R., & Helfat, C.E. (2003). Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 1011-1025.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Al-Aali, A., & Teece, D.J. (2014). International entrepreneurship and the theory of the (Long–Lived) international firm: a capabilities perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 95-116.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Bartholomew, S. (1997). National systems of biotechnology innovation: Complex interdependence in the global system. Journal of International Business Studies, 28, 241-266.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2003). Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1169-1208.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Bolton, D.L., & Lane, M.D. (2012). Individual entrepreneurial orientation: Development of a measurement instrument. Education Training, 54(2/3), 219-233.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Bowen, H.P., & De Clercq, D. (2008). Institutional context and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort. Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 747-767.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Bruton, G.D., Dess, G.G., & Janney, J.J. (2007). Knowledge management in technology-focused firms in emerging economies: Caveats on capabilities, networks, and real options. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24, 115-130.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Busenitz, L.W., Gomez, C., & Spencer, J.W. (2000). Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Academy of Management journal, 43(5), 994-1003.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Butler, K.C., & Joaquin, D.C. (1998). A note on political risk and the required return on foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 29, 599-607.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Carlos M.J. (2011). Social capital and dynamic capabilities in international performance of SMEs. Journal of Strategy and Management, 4(4), 404-421.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249-265.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Castanias, R.P., & Helfat, C.E. (1991). Managerial resources and rents. Journal of Management, 17(1), 155-171.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Chidlow, A., Wang, J., Liu, X., & Wei, Y. (2021). A co-evolution perspective of EMNE internationalization and institutions: An integrative framework of 5Cs. International Business Review, 30(4), 101843.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Clougherty, J.A. (2005). Antitrust holdup source, cross?national institutional variation, and corporate political strategy implications for domestic mergers in a global context. Strategic Management Journal, 26(8), 769-790.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Covin, J.G., & Slevin, D.P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75-87.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Crespo, N.F., Simoes, V.C., & Fontes, M. (2022). Uncovering the factors behind new ventures’ international performance: Capabilities, alertness and technological turbulence. European Management Journal, 40(3), 344-359.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Datta, D.K., Rajagopalan, N., & Zhang, Y. (2003). New CEO openness to change and strategic persistence: The moderating role of industry characteristics. British Journal of Management, 14(2), 101-114.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Davis, L., & North, D. (2011). Institutional change and American economic growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dhanaraj, C., & Khanna, T. (2011). Transforming mental models on emerging markets. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(4), 684-701.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Dunning, J.H. (2015). Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some empirical tests. The Eclectic Paradigm: A Framework for Synthesizing and Comparing Theories of International Business from Different Disciplines or Perspectives, 23-49.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Eisenhardt, K.M., & Martin, J.A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they?. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10?11), 1105-1121.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Etemad, H. (2004). Internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises: A grounded theoretical framework and an overview. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 21(1), 1.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Felicio, J.A., Caldeirinha, V.R., & Ribeiro-Navarrete, B. (2015). Corporate and individual global mind-set and internationalization of European SMEs. Journal of Business Research, 68(4), 797-802.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Fernandez-Mesa, A., & Alegre, J. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation and export intensity: Examining the interplay of organizational learning and innovation. International Business Review, 24(1), 148-156.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019-1051.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Fraser, J., & Oppenheim, J. (1997). What's new about globalization?. The McKinsey Quarterly, (2), 168.

Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1-2), 1-12.

Holbrook, D., Cohen, W.M., Hounshell, D.A., & Klepper, S. (2000). The nature, sources, and consequences of firm differences in the early history of the semiconductor industry. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10?11), 1017-1041.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Hoskisson, R.E., Eden, L., Lau, C.M., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249-267.

Hymer, S.H. (1960). The international operations of national firms, a study of direct foreign investment. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Ingram, P., & Silverman, B. (2002). The new institutionalism in strategic management. Elsevier.

Kalinic, I., Sarasvathy, S.D., & Forza, C. (2014). Expect the unexpected: Implications of effectual logic on the internationalization process. International Business Review, 23(3), 635-647.

Kobrin, S.J. (1981). Political assessment by international firms: models or methodologies? Journal of Policy Modeling, 3(2), 251-270.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Lee, S.H., Peng, M.W., & Barney, J.B. (2007). Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship development: A real options perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 257-272.

Levitt, T. (1983). The Globalization of Market: A Framework. Harvard Business Review.

Lewin, A.Y., & Kim, J. (2004). The nation state and culture as influences on organizational change and innovation. In Handbook of organizational change and development, 324-353.

Li, J. (2013). The internationalization of entrepreneurial firms from emerging economies: The roles of institutional transitions and market opportunities. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 11, 158-171.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Lu, Y., & Yao, J. (2006). Impact of state ownership and control mechanisms on the performance of group affiliated companies in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23, 485-503.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

MacLean, D., MacIntosh, R., & Seidl, D. (2015). Rethinking dynamic capabilities from a creative action perspective. Strategic Organization, 13(4), 340-352.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Martin, X. (2014). Institutional advantage. Global Strategy Journal, 4(1), 55-69.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

McDougall, P.P., & Oviatt, B.M. (1997). International Entrepreneurship Literature in the 1990s and Directions for Future Research. In D.L. Sexton, & R.W. Smilor (Eds.), Entrepreneurship 2000 Chicago.

Meyer, K.E., & Nguyen, H.V. (2005). Foreign investment strategies and sub?national institutions in emerging markets: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Management Studies, 42(1), 63-93.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Mudalige, D., Ismail, N.A., & Malek, M.A. (2019). Exploring the role of individual level and firm level dynamic capabilities in SMEs’ internationalization. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 17, 41-74.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Nelson, R.R. (1996). National innovation systems: a retrospective on a study. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Nigh, D. (1985). The effect of political events on United States direct foreign investment: A pooled time-series cross-sectional analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 1-17.

North, D.C. (1990). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5, 97-112.

Peng, M.W. (2003). Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 275-296.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Peng, M.W., Lee, S.H., & Wang, D.Y. (2005). What determines the scope of the firm over time? A focus on institutional relatedness. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 622-633.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Quigley, T., & Hambrick, D. (1950). Macrosocietal changes and executive effects on firm performance: A new explanation for the great rise in attributions of CEO significance.

Rezvani, M., Lashgari, M., & Yadolahi Farsi, J. (2019). International entrepreneurial alertness in opportunity discovery for market entry. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 21(2), 76-102.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Ring, P.S., Bigley, G.A., D'aunno, T., & Khanna, T. (2005). Introduction to special topic forum: Perspectives on how goverments matter. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 308-320.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Robinson, J.A., & Acemoglu, D. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty. London: Profile, 45-47.

Rosenbloom, R.S. (2000). Leadership, capabilities, and technological change: The transformation of NCR in the electronic era. Strategic Management Journal, 21(10?11), 1083-1103.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Rothaermel, F.T., & Hess, A.M. (2007). Building dynamic capabilities: Innovation driven by individual-, firm-, and network-level effects. Organization Science, 18(6), 898-921.

Scott, W.R. (1995). Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks. Cal: Sage Publications.

Sharma, L. (2018). A systematic review of the concept of entrepreneurial alertness. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 11(2), 217-233.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Teece, D.J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319-1350.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Teece, D.J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Teegen, H., Doh, J.P., & Vachani, S. (2004). The importance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in global governance and value creation: An international business research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 463-483.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Timmons, J.A., Spinelli, S., & Tan, Y. (2004). New venture creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st century. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Wan, W.P. (2005). Country resource environments, firm capabilities, and corporate diversification strategies. Journal of Management studies, 42(1), 161-182.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Wijanto, S.H. (2015). Metode penelitian menggunakan structural equation modeling dengan lisrel 9. Jakarta: Lembaga Penerbit Fakultas Ekonomi UI.

Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., Hoskisson, R.E., & Peng, M.W. (2005). Strategy research in emerging economies: Challenging the conventional wisdom. Journal of Management Studies, 42(1), 1-33.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Xu, D., & Meyer, K.E. (2013). Linking theory and context:‘Strategy research in emerging economies’ after Wright et al.(2005). Journal of Management Studies, 50(7), 1322-1346.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341-363.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Zhou, K.Z., Tse, D.K., & Li, J.J. (2006). Organizational changes in emerging economies: Drivers and consequences. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 248-263.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Received: 11-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. JLERI-23-5306; Editor assigned: 12-Jan-2023, PreQC No. JLERI-23-5306(PQ); Reviewed: 24-Jan- 2023, QC No. JLERI-23-5306; Published: 31-Jan-2023