Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 3

Implementation of the Registers for End-of-Life Decisions: First Case Study of 118 Municipalities of Central Italy

Giovanna Ricci, University of Camerino

Filippo Gibelli, University of Camerino

Giulio Nittari, University of Camerino

Silvano Leone, University of Camerino

Anna Maria Caraffa, University of Camerino

Ascanio Sirignano, University of Camerino

Citation Information: Ricci, G., Gibelli, F., Nittari, G., Leone, S., Caraffa, A.M., & Sirignano, A. (2022). Implementation of the registers for end-of-life decisions: First case study of 118 municipalities of central Italy. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(3), 1-15.

Abstract

Although law 219 of 2017 was the first end-of-life legislation in Italy, it still struggles to take root and be fully implemented more than two years since entering into force. Our work focuses on the preliminarily analysis of this legislation and then quantifies the number of advance care planning (ACP) dispositions filed in the municipal offices of the territory examined. We focus on three provinces of central Italy, Ascoli Piceno, Fermo and Teramo, to verify the deposition of ACP dispositions. Then, we analyze how many dispositions for advance care planning are deposited in the municipal registers. The research reveals critical barriers to the full implementation of this law. Only a small percentage of the 118 municipalities monitored have opened a municipal register to deposit ACP dispositions. There are also shortcomings in the establishment of a national database for the depositing of ACP dispositions, there has been a lack of inclusion of ACP dispositions in electronic health records, and hospitals still do not have real-time access to documents that disposers have made on their end of life plans.

Keywords

End of Life, Legal Proxy, Registers, Living Will.

Introduction

Italian law n. 219/2017, “Norms on informed consent and advance care planning dispositions”, enables the patient to self-determine his end-of-life plan with the tool of advance care planning dispositions. It was the first law to regulate this matter in Italy, and it came into force on January 31, 2018. Before the law, Italy was one of the few European countries that still did not expressly provide the opportunity for a person capable of self-determination to determine the treatment to be undertaken or not at the end of life and designating, if necessary, a person to ensure compliance. This legislation had been awaited for more than 35 years (Nurra, 2019). With this new law, the legislature regulated, along with ACP dispositions, informed consent (Viola et al., 2020).

These two fundamental issues of modern medicine were not regulated in Italy before this law. The subject of informed consent was regulated by the constitutional charter and by specific laws governing particular aspects of medical practice (e.g., organ donation, procreation, and abortion). Nevertheless, organic and homogeneous legislation on informed consent alone was absent. On the other hand, the end of life was “managed” by jurisprudential pronouncements of the courts of merit and legitimacy following the appeals of users who asked to interrupt their therapies (Vergallo & Spagnolo, 2019). The law marks the evolution of norms already widely established in Italian law but especially in medical deontology.

With law 219/17, the health care world had to deal with legislation on the end of life that affects a deontological context, an area that had already been governed for years by the Code of Medical Ethics. Article 38, “Advance Directives of Treatment”, had already substantially anticipated much of the law under consideration (Vergallo et al., 2016; Cecchi, 2016). Therefore, this new normative reality regulates informed consent, advances treatment dispositions, establishes the figure of the trustee and advances care planning. By their nature, ACP dispositions are a controversial tool on which to legislate. The temporal diversity between the documents’s drafting and its implementation is the expression of a future will. However, their interpretation and concrete application still present some limitations, especially in a reality that faces this regulation for the first time. However, respecting self-determination in health care choices is a complex area. It involves many subjects, such as the patient, the caregiver, the family, the team, and the trustee, and each of these subjects has unique values (Vergallo et al., 2018).

At present, some implementation and practical aspects of ACP dispositions are not fully realized. From this, our survey focuses on verifying whether the users benefit from the end-oflife law and whether the municipalities included in our surveyed territory have opened registers to file ACP dispositions. We also verify how many dispositions for advance care planning have been delivered according to the modalities provided by the law in the surveyed territory of three provinces of central Italy: Fermo and Ascoli Piceno in the Marche region and Teramo in Abruzzo.

Acp Dispositions In The End-Of-Life Law 219/2017: Law 219/2017 establishes that the patient must be of legal age to be able to make an advance disposition of treatment. With ACP dispositions, the disposer can express their wishes regarding health treatments, investigations, and therapeutic choices (Ciliberti et al., 2018). Due to the nature of the ACP dispositions, the able subject will decide, today and tomorrow, on a future and uncertain situation. To give concrete implementation abilities to the will of the patient, the figure of the “trustee” is established and identifiable in the subject who enjoys the trust of the disposer and who is authorized by him to represent him in relations with the doctor and with health facilities when he is no longer able to do so independently (Walker et al., 1995).

The trustee must formally accept the appointment by signing the document, which will be in the same form as that chosen by the settlor. The trustee will receive a copy of the appointment containing their duties for when the settlor is in a state that prevents him or her from expressing his or her wishes. The trustee may refuse the appointment and it may be revoked by the settlor without explanation. The ACP dispositions may also not indicate a trustee or that the trustee is no longer present or has become incapacitated. In this case, ACP dispositions remain effective with regard to the will of the writer, and if other needs arise, the judge may appoint a support administrator (Di-Paolo et al., 2019). The ACP dispositions can take the form of a public act, a notarized private writing or a private writing personally delivered to the disposer at the civil status office of the municipality of residence. The municipal administration will provide for its annotation and submission to the national ACP dispositions register accessible to health facilities. The establishment of registers with which to deposit the ACP dispositions is a due act by the local government to allow citizens of the municipality of residence to deposit their wills on the end of life. According to the law, there are other ways to deposit ACP dispositions, such as at hospital, notaries, and Italian consulates for Italian citizens abroad.

The doctor is obliged to respect the ACP dispositions; he can disregard them, with adequate motivation, in agreement with the trustee, in whole or in part, if they appear clearly incongruous or not corresponding to the current clinical condition of the patient or if there are therapies not foreseeable at the time of signing capable of offering real possibilities of improving the conditions of life. In case of a conflict between the doctor and the trustee, the tutelary judge will decide. These provisions can always be revoked or modified by the disposer (Botti & Vaccari, 2019). Once drafted, all ACP dispositions are transmitted and entered into the National Database established at the Ministry of Health as required by the 2018 budget law. The ACP dispositions database, regulated by Ministerial Decree no 168 of December 10, 2019 (Official Gazette of the Italian Republic, General Series n. 13 of 17/01/2020), was activated as of February 1, 2020. Our research attempts to identify the state of the establishment of municipal registers in the municipalities of central Italy, namely, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno in the Marche region and Teramo in Abruzzo.

The Table 1 below illustrates the different types of APC dispositions that exist.

| Table 1 Types of ACP Dispositions (Source: Italian Ministry of Health) | |

| ACP dispositions without appointment of trustee | The disposer submits ACP dispositions without naming the trustee. |

| ACP dispositions with appointment and acceptance of trustee | The settlor makes ACP dispositions while also appointing a trustee who accepts the appointment at the same time. Appointment of the trustee in this manner replaces any previous trustees appointed in the system (whether they accepted or not). |

| ACP dispositions with appointment of trustee not yet accepted | The disposer makes a disposition by also indicating a trustee who does not accept the appointment at the same time. The database accepts the disposition without making the appointed trustee active, who therefore cannot consult the disposer’s ACP dispositions until he or she has accepted the appointment by specific deed. Appointment without acceptance of the trustee does not invalidate any associated and active trustees for the settlor but replaces in the system any appointments pending acceptance. |

| Appointment of trustee with acceptance | The disposer, with this act, appoints a trustee who accepts the assignment at the same time. It is necessary for the presence of at least one valid ACP disposition already be signed and present in the National Data Bank. The system, upon receipt of the disposition, will associate the newly appointed trustee with the disposer. The appointment of the trustee in this way replaces in the system any previous trustees appointed previously. |

| Appointment of trustee without acceptance | The settlor, with this act, appoints a trustee who has not yet accepted the appointment. The database accepts the appointment without, however, making the appointed trustee active, who will therefore not be able to consult the disposer’s ACP dispositions until he or she has accepted the appointment by special act. The appointment without acceptance of the trustee does not invalidate any associated and active trustees for the settlor but replaces in the system any appointments awaiting acceptance. |

| Revocation of ACP dispositions | The disposer revokes a single ACP disposition transmitted previously. To be able to cancel a single ACP disposition, the disposer must provide the “act number” assigned by the system when accepting the original disposition. When there is more than one disposition for the disposer, the links to the eventual trustee will remain valid. |

| Revocation of trustee appointment | With this type of act, the settlor revokes the previously appointed trustee and invalidates the links between himself and the same trustee in the National Data Bank. |

| Revocation of all previously transmitted ACP dispositions | This type of act includes any type of act not already provided for by the previous types. The description of the type of document must be clearly and concisely specified |

Objective of the Research

The objective of this work is to verify the state of municipal ACP dispositions registers almost three years after the enactment of the Italian law and therefore whether citizens can actually dispose of this right by depositing ACP dispositions in their municipalities of residence. Advanced treatment dispositions, drawn up in the manner of law 219/17, have been transmitted and entered into the National Database established at the Ministry of Health active since February 1, 2020.

In October 2019, the Luca Coscioni Association conducted a similar survey throughout the country to verify which municipalities had set up municipal registers and the number of ACP dispositions actually delivered. At present, this is the only survey to have been carried out since the enactment of the law. Throughout Italy in 2019, only 73 municipalities responded to the survey of the Luca Coscioni Association, among which 39,337 ACP dispositions were deposited. The survey showed an increase in the filing of ACP dispositions of 22% in the first three months of 2019 relative to the same months of the previous year. In addition, the association highlighted a lack, in all Italian regions, of the inclusion of ACP dispositions in health records, as required by Article 1 of law 219/17. In the same study, poor, if not nonexistent, information on the subject emerged, identifying this as a possible cause of citizens’ lack of success in depositing their own provisions. The study also highlighted the 20 “worst” municipalities in terms of the ratio of advance treatment instructions deposited/population (Trapani, Ragusa, Viterbo, Catanzaro, and Lamezia) and the “best” municipalities (Pesaro, Matera and Varese) for the number of advance treatment instructions deposited in relation to the population. In the province of Pesaro, 712 ACP dispositions were filed with an incidence of 1 every 133 inhabitants; in the province of Matera, 413 ACP dispositions were filed, equal to 1 in every 146 inhabitants; and in the province of Varese, 523 ACP dispositions were filed, equal to 1 in every 154 inhabitants. In the survey of the Luca Coscioni Association, the provinces of our research had not produced a response, so we thought it would be interesting to see if there had been any change in the ACP disposition municipal registers a year later.

Methodology

Our survey examines 118 municipalities of central Italy belonging to the provinces of Ascoli Piceno, Fermo and Teramo. This work represents a first analysis designed to extend the previous survey to other Italian provinces and regions. The research was carried out during a unique period of a year ravaged by the COVID-19 emergency, which severely tested municipal administrations, forcing many employees to work remotely from home and creating a backlog of work to be carried out in person, further overburdening municipal offices. The survey was conducted in multiple phases during the months of June through December 2020.

The phases of our work proceeded as follows:

1. Verification of the opening of ACP disposition registers in the studied municipalities (June-August, 2020).

2. Ascertaining the number of ACP dispositions filed (September-November, 2020).

The research was carried out personally by some of the researchers. The first phase was carried out online to check whether the institutional site of the municipality mentioned the possibility of filing ACP dispositions as required by law 219/17. After the first verification, we proceeded to contact each municipality by email, indicating the purpose of the research and asking for the number of ACP dispositions deposited on August 31, 2020. This email was answered by a small number of municipalities. This phase ran from August 2020 to the end of September 2020. Due to the limited response from the municipal offices, an additional email was sent in August, since we had received several responses that were not considered adequate.

The second phase involved telephoning the municipalities that had not responded to the email sent in September. Over the telephone, we asked for the number of ACP dispositions deposited in the municipal registers to be provided via email. After this phase, many of the administrations contacted sent the data. We considered it necessary to carry out a second subphase, concluding the survey carried out between October and November. We again telephoned municipalities requesting confirmation of the number of advance treatment agreements filed. The final and conclusive data of the survey were obtained in the first days of December 2020.

Results

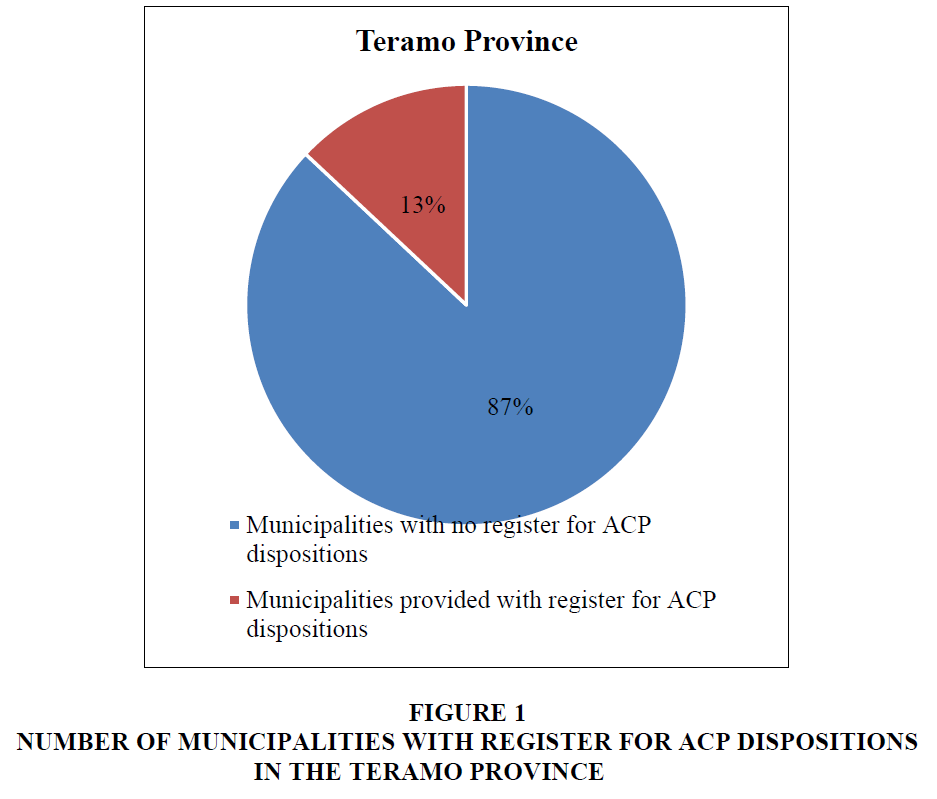

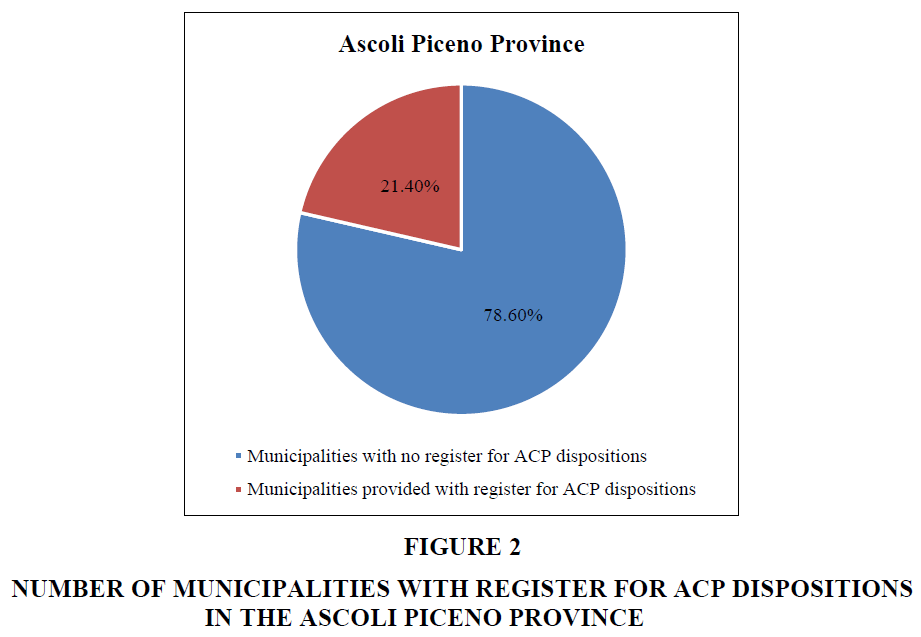

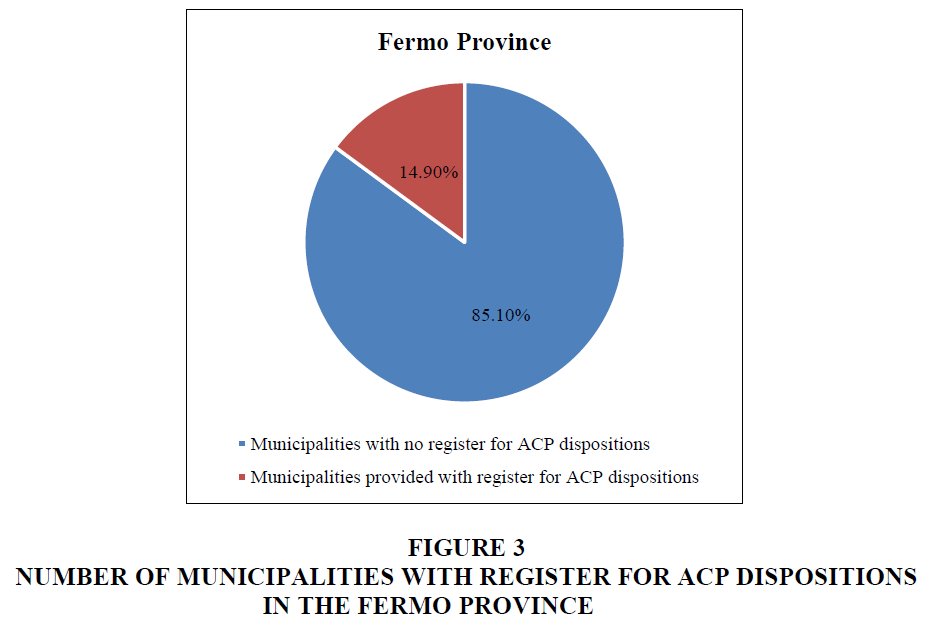

The data collected in our survey are not encouraging in terms of the number of registers set up or in terms of the number of ACP dispositions deposited. Regarding the number of municipalities that have set up municipal registers, despite the substantial number of municipalities within the provinces considered, few have set up a register for ACP dispositions (Table 2 and Figure 1, 2 & 3).

| Table 2 Number of Municipalities with Registers for ACP Provisions in the 3 Italian Provinces Examined in Our Study | |||

| Province | Total Number of Municipalities | Number of Municipalities with registers for ACP dispositions | % |

| Ascoli Piceno | 33 | 9 | 21,4 |

| Fermo | 40 | 7 | 14,9 |

| Teramo | 45 | 7 | 13 |

Of the 40 municipalities in the province of Fermo, 7 have established registries, equal to 14.9%. Among these are the most populous municipalities in the province, including Fermo, Porto Sant’Elpidio, Sant’Elpidio a mare, Porto San Giorgio, Montegranaro, Montegiorgio, and Amandola. In the province of Ascoli Piceno, of 33 municipalities, 9 have instituted the ACP dispositions registry, representing 21.4%. Additionally, in this province, the most populous municipalities have opened registers; six have populations of more than five thousand units (Ascoli Piceno, San Benedetto del Tronto, Grottammare, Monteprandone, Spinetoli, and Cupra Marittima). In the province of Ascoli, however, a town with only 922 inhabitants, Cossignano, has instituted the register.

In the province of Teramo, of 47 municipalities, including the municipality of Teramo, only 7 (13%) have established the ACP dispositions register. In this province, some small municipalities have established the register while some much larger municipalities have not, and among these, the municipality of Teramo stands out at both the provincial and municipal levels. The most populous municipalities that have instituted the registry are the coastal municipalities Roseto degli Abruzzi, Martinsicuro and Alba Adriatica, with populations of over ten thousand units, and those with populations of less than ten thousand units include Castellalto, Notaresco, Torricella Sicura, and Penna Sant’Andrea. Alba Adriatica has set up the register but has not provided the number of ACP dispositions deposited. The same applies for Porto Sant’Elpidio and Sant’Elpidio a mare.

While the municipality of Silvi was proceeding with the establishment of the register from verbal communications in June 2020, the municipality had not completed the task at the time of data verification. Regarding the number of ACP dispositions delivered by the population in the registers of the municipalities of residence, 292 documents had been delivered in Fermo, 573 had been delivered in Ascoli Piceno and 546 had been delivered in Teramo.

The Table 3, 4, & 5 below present the statistics for the municipalities. The Tables show in red those municipalities that have set up ACP disposition registers but that have not disclosed the number of ACP dispositions included in these registers.

| Table 3 Number of ACP Dispositions Deposited in the Registers of Municipalities of the Fermo Province | |

| Municipalities in the Fermo province | Number of APC dispositions |

| Amandola | 7 |

| Montegiorgio | 13 |

| Montegranaro | 37 |

| Fermo | 186 |

| Porto San Giorgio | 49 |

| Chart-1. Immune-related Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism frequencies (%) under different ICIs. | Unknown |

| Chart-1. Immune-related Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism frequencies (%) under different ICIs. | Unknown |

| Table 4 Number of ACP Dispositions Deposited in the Registers of Municipalities of the Ascoli Piceno Province | |

| Municipalities in the Ascoli Piceno province | Number of APC dispositions |

| Ascoli Piceno | Unknown |

| San Benedetto del Tronto | 276 |

| Grottammare | 131 |

| Monteprandone | 128 |

| Spinetoli | 17 |

| Cupra Marittima | Unknown |

| Cossignano | 5 |

| Maltignano | 11 |

| Castorano | 5 |

| Table 5 Number of ACP Dispositions Deposited in the Registers of Municipalities of the Teramo Province | |

| Municipalities in the Teramo province | Number of APC dispositions |

| Roseto | 347 |

| Martinsicuro | 78 |

| Alba Adriatica | Unknown |

| Notaresco | 49 |

| Torricella Sicura | Unknown |

| Penna Sant’Andrea | Unknown |

| Castellalto | 72 |

In the Tables 6, 7 & 8 below, the populations by age group for the 3 provinces included in this study are shown. The data were processed by the Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) and refer to the population as of January 1, 2020.

| Table 6 2020 Population Distribution in the Ascoli Piceno Province | ||||

| Age groups | Males | Females | Total | |

| % | ||||

| 20-24 | 5.306 52.8% |

4.748 47.2% |

10.054 | 4.9% |

| 25-29 | 5.580 52.6% |

5.034 47.4% |

10.614 | 5.1% |

| 30-34 | 5.609 50.5% |

5.488 49.5% |

11.097 | 5.4% |

| 35-39 | 5.968 50.5% |

5.857 49.5% |

11.825 | 5.7% |

| 40-44 | 6.706 48.9% |

7.019 51.1% |

13.725 | 6.7% |

| 45-49 | 7.779 49.2% |

8.029 50.8% |

15.808 | 7.7% |

| 50-54 | 8.142 48.8% |

8.546 51.2% |

16.688 | 8.1% |

| 55-59 | 7.838 48.5% |

8.317 51.5% |

16.155 | 7.8% |

| 60-64 | 6.712 46.8% |

7.644 53.2% |

14.356 | 7.0% |

| 65-69 | 6.054 47.3% |

6.736 52.7% |

12.790 | 6.2% |

| 70-74 | 5.488 46.3% |

6.373 53.7% |

11.861 | 5.7% |

| 75-79 | 4.522 46.0% |

5.299 54.0% |

9.821 | 4.8% |

| 80-84 | 3.898 42.9% |

5.180 57.1% |

9.078 | 4.4% |

| 85-89 | 2.205 38.2% |

3.563 61.8% |

5.768 | 2.8% |

| 90-94 | 869 32.4% |

1.817 67.6% |

2.686 | 1.3% |

| 95-99 | 152 22.9% |

513 77.1% |

665 | 0.3% |

| 100+ | 12 19.4% |

50 80.6% |

62 | 0.0% |

| Total | 100.056 48.5% |

106.307 51.5% |

206.363 | 100.0% |

| Table 7 2020 Population Distribution in the Fermo Province | ||||

| Age groups | Males | Females | Total | |

| % | ||||

| 20-24 | 4.571 53.1% |

4.040 46.9% |

8.611 | 5.0% |

| 25-29 | 4.443 51.3% |

4.225 48.7% |

8.668 | 5.0% |

| 30-34 | 4.748 50.5% |

4.653 49.5% |

9.401 | 5.4% |

| 35-39 | 5.070 50.3% |

5.014 49.7% |

10.084 | 5.8% |

| 40-44 | 6.023 50.0% |

6.016 50.0% |

12.039 | 7.0% |

| 45-49 | 6.362 48.9% |

6.651 51.1% |

13.013 | 7.5% |

| 50-54 | 6.679 49.0% |

6.943 51.0% |

13.622 | 7.9% |

| 55-59 | 6.583 49.4% |

6.737 50.6% |

13.320 | 7.7% |

| 60-64 | 5.844 48.2% |

6.292 51.8% |

12.136 | 7.0% |

| 65-69 | 5.171 48.6% |

5.463 51.4% |

10.634 | 6.1% |

| 70-74 | 4.641 47.6% |

5.108 52.4% |

9.749 | 5.6% |

| 75-79 | 3.426 45.0% |

4.195 55.0% |

7.621 | 4.4% |

| 80-84 | 3.403 43.2% |

4.476 56.8% |

7.879 | 4.6% |

| 85-89 | 1.854 38.1% |

3.015 61.9% |

4.869 | 2.8% |

| 90-94 | 741 32.5% |

1.536 67.5% |

2.277 | 1.3% |

| 95-99 | 126 23.8% |

404 76.2% |

530 | 0.3% |

| 100+ | 7 14.9% |

40 85.1% |

47 | 0.0% |

| Total | 84.503 48.8% |

88.501 51.2% |

173.0004 | 100.0% |

| Table 8 2020 Population Distribution in the Teramo Province | ||||

| Age groups | Males | Females | Total | |

| % | ||||

| 20-24 | 7.856 52.4% |

7.125 47.6% |

14.981 | 4.9% |

| 25-29 | 8.641 51.3% |

8.190 48.7% |

16.831 | 5.5% |

| 30-34 | 8.890 50.8% |

8.627 49.2% |

17.517 | 5.7% |

| 35-39 | 9.710 50.9% |

9.348 49.1% |

19.058 | 6.2% |

| 40-44 | 10.639 49.9% |

10.682 50.1% |

21.321 | 6.9% |

| 45-49 | 11.837 49.2% |

12.203 50.8% |

24.040 | 7.8% |

| 50-54 | 12.738 49.4% |

13.035 50.6% |

25.773 | 8.4% |

| 55-59 | 11.357 48.7% |

11.963 51.3% |

23.320 | 7.6% |

| 60-64 | 10.069 48.7% |

10.626 51.3% |

20.695 | 6.7% |

| 65-69 | 8.717 47.9% |

9.482 52.1% |

18.199 | 5.9% |

| 70-74 | 7.901 47.4% |

8.784 52.6% |

16.685 | 5.4% |

| 75-79 | 6.142 46.2% |

7.151 53.8% |

13.293 | 4.3% |

| 80-84 | 5.091 42.8% |

6.815 57.2% |

11.906 | 3.9% |

| 85-89 | 2.861 37.5% |

4.774 62.5% |

7.635 | 2.5% |

| 90-94 | 1.036 31.1% |

2.295 68.9% |

3.331 | 1.1% |

| 95-99 | 184 22.1% |

647 77.9% |

831 | 0.3% |

| 100+ | 12 14.5% |

71 85.5% |

83 | 0.0% |

| Total | 150.398 48.9% |

157.014 51.1% |

307.412 | 100.0% |

Discussion

A first piece of evidence that emerges from the data is that in the more populous municipalities, the APC dispositions register has generally been set up, while in municipalities with smaller populations, it seems that the opening of registries is not yet a priority. The more resident citizens there are, the more frequently APC disposition registers have been opened. A further finding concerns the geographic distribution: from the data, it seems that maritime municipalities are more inclined to set up registers, while inland municipalities appear less sensitive to the opening of registers. In the province of Ascoli Piceno, maritime municipalities represent three out of six of those with populations of over five thousand units, while in the Teramo area, all coastal municipalities have populations over ten thousand units. In contrast, in the Fermo area, there is substantial homogeneity between coastal and inland municipalities in the establishment of APC disposition registers. Another consideration relates to the relationship between the age of the population and the establishment of registers. Upon analysing the ages of the resident populations of the municipalities in which the registries are established, we find that where the prevailing population is between 40 and 54 years of age, more registries have been opened.

From the ISTAT Tables for the population age cohorts of the provinces, in the province of Fermo (Table 7), there is a large population ranging from forty to fifty-four years of age with the majority of the population being over 50 years of age: 7.0% of the population is 40-44 years of age, 7.5% is 45-49 years of age, and 7.9%, the largely segment, is 50-54 years of age. The situation is the same in the province of Ascoli Piceno (Table 6); while 6.7% of the population is 40-44 years of age and 7.7% is 45-49 years of age, the 50-54 year old cohort makes up the largest proportion of the population, equal to 8.1%. The province of Teramo (Table 8) has a similar situation. The 40-44 age bracket makes up 6.9% of the population, the 45-49 age bracket makes up 7.8%, and the 50-54 age bracket includes the most residents, equal to 8.4%. For the three provinces, from a demographic perspective and in terms the scarcity of the APC dispositions filed, we find a population composed mainly of persons of 50 to 54 years of age and with few APC dispositions relative to the number of inhabitants in each municipality.

The advance care planning (ACP) dispositions provided by law 219/2017 represent one of the most important milestones achieved by Italian legislative production in recent decades. However, it seems that there is still a long way to go before its full implementation. The establishment of the national database for the registration of APC dispositions (law No. 205/2017) did not determine by which subjects and in what manner the APC dispositions should be transmitted to the same bank. This was provided by a regulation of the Ministry of Health issued on December 10, 2019, which in art. 11 have provided that, within sixty days of the activation of the data bank, the names of the disposers must be transmitted to the bank along with the copy of their APC dispositions within one hundred and eighty days. Upon analysing annual reports to the Chambers of Parliament required by law 219, 62,030 DATs were found to be delivered to the civil status offices of municipalities as of March 31, 2018 according to data provided by the Ministry of the Interior. Despite this important milestone, users are still struggling to take advantage of this opportunity in large numbers.

From our investigation, we identify two impediments to the full implementation of the law: one of a normative-organizational nature at the expense of public administration and another of an informative-social nature with respect to users. Regarding regulatoryorganizational issues, it can be highlighted that the implementation of the entire procedure required a series of decrees outlining modalities of the transfer of APC dispositions from municipalities to health facilities. This is fundamental determining in real time whether the subject arriving at the hospital facility, even in an emergency, has drawn up APC dispositions. The multiyear budget law of 2018-2020 in art.1, paragraph 419 provided that within 180 days of the law’s entry into force, the Ministry of Health should issue a decree to establish procedures for the registration of APC dispositions in the national database. The same report also raised interpretative doubts about the correct application of the rule, such as in terms of investing in the advisory competence of the Council of State expressed in Opinion No. 1991 of July 31, 2018. The Council of State, stressing the complexity of the regulatory framework, provided elements for effectively implementing the legislative precepts.

On the basis of these clarifications, an outline of a ministerial decree was formulated that would regulate the procedures for registering the APC dispositions in the national database set up at the Ministry of Health and its updating in the event of renewal, modification or revocation; the functioning and information content of the national database; procedures for accessing the database by the legitimated parties (the attending physician and the trustee in the event of a case of an inability to self-determine); subjects delegated to contribute to the database (the civil status offices of municipalities of residence of the disposers; the Italian diplomatic or consular representations abroad; and notaries and heads of competent organizational units in the regions that have adopted telematic methods for managing medical records, electronic health files or other forms of computerized data management of those enrolled in the National Health Service); online technical modalities or PEC acquisition of the APC dispositions collected by the authorized subjects; the succession of declarations by the same disposer, both in the substitution of the previous ones and in terms of the modification or integration of declarations previously made; and the transitional regime concerning the declarations made prior to the creation of the national database. Otherwise, informational-social issues refer to the fact that the population should have been informed extensively about this law and right to formulate APC dispositions.

Unfortunately, as we were able to ascertain, registers for the filing of APC dispositions have still not opened in many municipalities. In some municipalities observed by our survey, there have been information campaigns and public conferences to raise awareness about the possibility of formulating APC dispositions but only for insiders and failing to disseminate the legislation. Following our survey of three provincial capitals, Ascoli Piceno, Teramo and Fermo, only two had opened municipal registers for APC dispositions (Fermo and Ascoli Piceno). Among the three provinces, the highest percentage of APC disposition register activation is in Ascoli Piceno at 21.4%, while the figures for Fermo and Teramo are 14.9% and 13%, respectively. These levels frighteningly low relative to the population. We wondered whether the failure to set up the registers is attributable solely to a mere failure on the part of the municipal administration or to substantial indifference on the part of public opinion and politics on the end of life.

Alternatively, as many believe that the end of life is a condition that affects only sick and/or elderly people, the issue is not recognised by most potential users, confirming a lack of information. It would be cynical to believe that since a certain condition does not concern someone specifically, then it is not worthy of interest, as if the APC dispositions were written only by those in pathological and serious circumstances. One could speculate that the lack of awareness of law 219/17 may be cultural in nature: for a full application of the legislation, it will be necessary to overcome the concept that death as something unrelated to life and adopt a new perspective. Regardless of what happens after death, whether mere decomposition or new existence, the human being is the holder of a quality that cannot be denied and that is the dignity of existence, and when existence itself is no longer dignified for the subject who suffers a certain disease or condition, then and only then must this subject be able to decide about his own life. The issue of law 219/2017 is much more complex than one of mere written consent or of seeing the doctor-patient relationship in a new light, as it affects a current issue and one that will become increasingly cogent with constant advances in medicine that prolong the life of the patient (Veshi & Neitzke, 2015).

Conclusion

Finally, we note a social consideration: what we seem to notice is a lack of preparation and information in the community about the possibility of drawing up APC dispositions. A few meetings and conferences have been held, especially for professionals, but it would be better for each community to provide real information on people's rights, on the possibility of expressing their wishes, on treatment arrangements and on shared care planning, which is also possible and regulated by the same law, so that people can freely determine whether to exercise a right due at the end of life or allow science and doctors to continue to exercise, in science and conscience, the art of medicine even at the end of life.

References

Botti, C., & Vaccari, A. (2019). End?of?life decision?making and advance care directives in Italy. A report and moral appraisal of recent legal provisions. Bioethics, 33(7), 842-848.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cecchi, R. (2016). Comment on the static evolution of the new Italian code of medical ethics. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 30(1), 2755-2757.

Ciliberti, R., Gulino, M., & Gorini, I. (2018). New italian law about end of life: Self-determination and shared care pathway. Recenti Progressi in Medicina, 109(5), 267-271.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Di-Paolo, M., Gori, F., Papi, L., & Turillazzi, E. (2019). A review and analysis of new Italian law 219/2017:provisions for informed consent and advance directives treatment. BMC Medical Ethics, 20(1), 1-7.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nurra A. (2019). The right to self-determination: Advance treatment dispositions. Giurisprudenza Penale Web.

Vergallo, G.M., Busardò, F.P., Berretta, P., Marinelli, E., & Zaami, S. (2018). Advance healthcare directives: moving towards a universally recognized right. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences, 22(10), 2915-2916.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vergallo, G., & Spagnolo, A. G. (2019). Informed consent and advance care directives: Cornerstones and outstanding issues in the newly enacted italian legislation. The Linacre Quarterly, 86(2-3), 188-197.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vergallo, G., Busardò, F.P., Zaami, S., & Marinelli, E. (2016). The static evolution of the new Italian code of medical ethics. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 20(3), 575-580.

Veshi, D., & Neitzke, G. (2015). Living wills in Italy: ethical and comparative law approaches. European Journal of Health Law, 22(1), 38-60.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Viola, R V., Di Fazio, N., Del Fante, Z., Fazio, V., Volonnino, G., Romano, S., & Arcangeli, M. (2020). Rules on informed consent and advance directives at the endof-life: The new Italian law. La Clinica Terapeutica, 171(2), 94-96.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Walker, R.M., Schonwetter, R.S., Kramer, D.R., & Robinson, B.E. (1995). Living wills and resuscitation preferences in an elderly population. Archives of Internal Medicine, 155(2), 171-175.

Received: 12-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-9721; Editor assigned: 15-Nov-2021, PreQC No. JLERI-21-9721(PQ); Reviewed: 29- Nov-2021, QC No. JLERI-21-9721; Revised: 14-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-9721(R); Published: 21-Feb-2022