Research Article: 2024 Vol: 27 Issue: 3

Impact of Government Policies on the Growth of SMEs in the Nigerian Economy

Kehinde Segun, Covenant University

Bankole Oluseun Ayodele, Federal Polytechnic Ilaro

Busola Simon-Ilogo, Covenant University

Kehinde Kemi, Anchor University

Citation Information: Segun, K., Ayodele, B.O., Simon-Ilogo, B., & Kemi, k. (2024). Impact of government policies on the growth of smes in the nigerian economy. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 27(3), 1-11.

Abstract

The growth of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) is pivotal to the economic development of Nigeria. This study examines the impact of government policies on the growth trajectory of SMEs within the Nigerian economy. Through a comprehensive review of existing literature and analysis of relevant empirical data, the research evaluates the effectiveness of various government interventions, regulations, and support mechanisms aimed at fostering the development of SMEs. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for policymakers, business leaders, and stakeholders seeking to formulate and implement policies that promote the robust growth of SMEs, thereby driving economic diversification, job creation, and inclusive growth in Nigeria

Keywords

SMEs, Government policies, Economic growth, Nigeria, Entrepreneurship.

Introduction

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) have been recognized as driving force for economic growth in any nation. Empirical evidences have shown that they contribute to employment, alleviate poverty and increase productivity level in a nation. In recognition of the role of SMEs in the economic growth process of Nigeria, government has taken concerted efforts to foster the growth of SMEs and also develop entrepreneurship. SMEs are of necessity to a nation’s industrialization process. One foremost way of promoting SMEs is by having easy access to finance. Finance is of high importance to the growth of SMEs. Afolabi (2013) noted that a major gap in Nigeria’s industrial development process in the past years has been the absence of a strong and virile SMEs sector attributable to the reluctance of banks especially commercial banks to lend to the sector. Commercial banks through their intermediation role are meant to provide financial succor to SMEs. Prior researchers have identified lack of finance as a threat to the performance of SMEs (Aernold, 1998).

For SMEs to perform their role in the economy, they need adequate funds in terms of short and long-term loans. Adequate financing of SMEs is paramount to their survival, as it has been recorded in literature that financial constraint is one of the main reasons SMEs fail in Nigeria (Ayeni-Agbaje et al., 2015). Osoba argued that financing strength is the main determinant of small and medium enterprises growth in developing countries. There is no gainsaying that finance would boost the performance of SMEs if adequate and optimally utilized. The dearth of funds in these businesses is capable of crippling their operations. Lack of funding for SMEs creates obstacles in allowing them contribute to economic growth and development. Onugu ranked access to finance as the second problem faced by SMEs in Nigeria. Commercial banks are often reluctant to lend to SMEs because of the perceived risky nature of SMEs by them. Analysis of the annual trend in the share of commercial bank credit to small-scale industries indicates a decline from about 7.5 per cent in 2003 to less than 1% in 2006 and a further decline in 2012 to 0.14 percent. The decline shows that commercial banks have less preference to lend to SMEs. The main identified gap that necessitated this study is the perceived problem of inadequate financing from commercial banks in Nigeria to SMEs. Therefore, this study aims at investigating the effect of commercial banks in financing SMEs in Nigeria (Aremu, 2004).

In spite of continuous policy strategies to attract credits to the SMEs, most Nigerian SMEs have remained unattractive for bank credits supply (Aremu et al., 2011). For instance, as indicated in Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) reports, almost throughout the regulatory era, commercial bank’s loans and advances to the SMEs sector deviated persistently from prescribed minimum. Furthermore, the enhanced financial intermediation in the economy following the financial reforms of the 1986, credits to SMEs as a proportion of total banking credits has not improved significantly (Evbuomwan et al., 2012). Afolabi asserted that one of the problems faced by SMEs operators in Nigeria is that government does not give chance or consider them when making policy in which priority is given to large organizations. This makes financing the main constraining factor to SMEs growth and hinders their potentials for enhancing economic growth in Nigeria. Available information from CBN,2012 shows that, as at 1992 commercial bank loan to SMEs as Percentage of total credit was 27.04% in 1997 and decreases to 8.68%, 0.85% and 0.14% in 2002, 2007 and 2010 while 2012 recorded 0.15%. Consequently, many SMEs in the country have continued to rely heavily on internally generated funds, which have tended to limit their scope of operation.

Literature Review

The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) identified fifty definitions of small scale business in seventy-five different countries based on parameters such as installed capacity utilization, output, employment, capital, type of country or other criteria, which have more relevance to the industrial policies of the specific country. However, it has been suggested that the SMEs sub-sector may comprise about 87 per cent of all firms operating in Nigeria, excluding informal - enterprises. USAID defined enterprises as informal businesses employing five or fewer workers including unpaid family labour; small enterprises as those operating in the formal sector with five to twenty employees; and medium enterprises as those employing 21 to 50 employees. Egbuogu noted that definitions of SMEs vary both between countries and between continents (Rasak, 2012). The major criteria use in the definitions according to Carpenter could include various combinations of the following: Number of employees, financial strength, Sales value, Relative size, Initial capital outlay and Types of industry however, stressed the indicators prominent in most definitions namely, size of capital investment (fixed assets), value of annual turnover (gross output) and number of paid employees (Akingunola, 2011).

The Nigerian Government has used various definitions and criteria in identifying what is referred to as micro and small sized enterprises. At certain point in time, it used investment in machinery and equipment and working capital. At another time, the capital cost and turnover were used. However, the Federal Ministry of Industry, under whose jurisdiction the micro and small sized enterprises are, has adopted a somewhat flexible definition especially as to the values of installed fixed cost. Amidst several definitions provided by the Government and its attendant agency, the National Council on Industry defined micro enterprises as an industry whose total project cost excluding cost of land but including working capital is not more than N500,000:00 (i.e. US$50,000). Small scale enterprises on the other hand is defined by the council as an industry whose total project cost excluding cost of land and including working capital does not exceed N5m (i.e. US$500,000).

Furthermore, the National Council on Industry of Nigeria at its 9th Meeting adopted the report of its Sub-Committee on Classification of Industrial Enterprises in Nigeria and approved a new set of classifications and definitions of the cottage/micro and small scale enterprises. According to the Council, cottage/micro industry is an industry whose total cost, including working capital but excluding cost of land, is not more than N1 million and a labour size of not more than 10 workers; while small scale enterprises is an industry whose total cost, including working capital but excluding cost of land, is over N1 million but mot more than N40 million and a labour size of between 11 and 35 workers. Stanley and Morse classified industries into eight by size. They adopted the functional approach, and emphasized how small and medium sized industries differ from larger industries by bringing out clearly the differing characteristics which include little specialization, close personal contact of management with production workers and lack of access to capital. They argued that establishments employing not less than 100 workers should be defined as medium sized whereas those with less than 100 employees be defined as small sized. The UNDP/UNIDO Report, 2000 noted that while the limit of 10 workers for Micro/Cottage Industries was flexible enough to capture about 95% of rural industries and micro enterprises in this category, the ceiling of N1.0 million may however exclude about 40% of such entrepreneurs with modest factory buildings and basic infrastructures which they require (e.g. access road, generator, bore-hole wells, storage facilities etc). In addition, while the ceilings of N40 million for Small Scale Industries and N150 million for Medium Industries are still substantially captive for these categories, the limits of 35 and 100 workers respectively were not based on the actual structure of manufacturing enterprises in the country (Afonja, 1999).

The Nigeria bank for commerce and industries (NBCI) adopted a definition for the period 1985-1990 (current valid) in which it defined small scale industry as “an industry with capital not exceeding N750, 000 including working capital but excluding cost of land. Also Central Bank of Nigeria maintains that small scale enterprises shall include cottage industries and defined them as enterprises whose total cost excluding cost of land but including working capital does not exceed N10 million. Okorie observes that small scale business is any business whose total assets in capital equipment plant and employing fewer than 50 employers and must be wholly indigenously owned. Ihenetu considered business they fall within the category of business with paid up capital of N750, 000 expect those businesses owned by the government or shareholders which in some cases are very few (Etim, 2010). Small forms range from the sole trader, small partnership to the privately owned industrial company. Ezeigbe defines a small scale business as one that operates under strict amount of capital that which its assets and liabilities cannot enable it obtain loan a assistance from any other financial institution. This may be its inability to mortgage its assets or having a reasonable asset that would guiltily it for a loan within the laid down rules for loan granting.

Importance of SMEs to Nigeria Economic Development

It is important to note that the development of entrepreneurs cannot be overemphasized and the role they play in economic development and how they are financed through both formal and informal sources. The development experience of many countries indicates that SMEs can meaningfully contribute to the attainment of many development objectives. These include output expansion, employment generation, even location of industries among regions of the countries, income redistribution, promotion of indigenous entrepreneurship and technology as well as production of intermediate goods to strengthen inter and intra industrial leakages.

Never the less, the extent to which the opportunities offered by SMEs are exploited and their contributions maximize in any economy depends on the enabling environment created through the provision of requisite infrastructures facilities such as roads, telecommunication, power etc. and pursuit of policies such as concretionary financing that encourage and strengthen the growth of the sector. Although the recognition of the economic importance of SMEs to the Nigerian economy is only a recent development, today the contributions of the sector to the economy are no longer contestable. The contribution of SMEs to manufacturing output and gross domestic product (GDP) is appreciable. In the area of employment generation, SMEs accounted for about 70 per cent of the industrial employment in 1987 and the situation has remained largely the same, the same is the case in other developing economy as it is estimated that SMEs employ 22 per cent of the adult population in those countries, specifically, the sector employs about 15.5 per cent and 13.9 per cent of the labour force, which is higher employment growth than micro and large scale enterprises (5 per cent and 11 per cent) in Ghana and Malawi respectively (Gunu, 2004).

However, importance of SMEs as catalyst to economic growth and national development has been long recognized and is obviously a basic reason for their promotion in developed economy. For instance, the Bolton committee of inquiry established in United Kingdom in 1968 to examine the role of small scale enterprise in the British economy ideally describes two important roles of these enterprises as breeding ground of new industries and source of dynamic competition, even in the most buoyant economy, such as the United states of America, SMEs have played an important role in the country's transition from the industrial age to the post- industrial technology era. SMEs are divided into Medium Scale Enterprise (MSE), Small Scale Enterprise (SSE) and Micro Enterprises (ME).The federal ministry of industries defines a Medium Scale Enterprise as any company with operating assets less than 200 million and employing less than 200 persons. A Small Scale Enterprise on the other hand, is one that has total assets less than 50 million, with less than 100 employees. Annual turnover is not considered in its definition of a SME. The National Economic Reconstruction Fund(NERFUND) defines a SSE as one whose total assets is less than 10 million but made no reference to either its annual turnover or the number of employee(WORLD BANK,2010. Two fundamental financing concepts in the development of SMEs, the formal and informal forms of financing have been identified by the previous researcher, scholars and practitioners. The findings were that among the most popular of the formal sources of financing, the commercial banks and the development banks remains the formal sources of finance for enterprises (Gujarati, 2003).

The informal source comprising personal savings, borrowing from friends and relatives and comparative credits has also been identified as potential sources of financing SMEs. Research works have been conducted on SME financing policies and strategies for its development and SME credit delivery strategies in Nigeria. The World Bank conducted research survey on SME access to formal financing institutions credits and found that 85 per cent of Nigerian firms had relationship with banks, not all of them had access to external credit. Schneider- Bartholdi and others have on the hand confirmed the significant contribution of SMEs to macro-economic development of nations (Udechukwu, 2003).

The problem of SME financing has received the most tremendous research efforts from researchers. The research gap that still exists in spite of these research efforts is the capacity of other financing options to fill the vacuum created by the failure of the formal financial institutions to supply the financial needs of SMEs in Nigeria. Aruwa notes that since the banks have demonstrated their inability to assume and manage the interest of SMEs, the informal savings schemes not only do they fill the vacuum created but they also constitute a new form of capital accumulation based on solidarity and co-operation between communities and businesses. Golis identified financing opportunities in ventures capital for SMEs. The Small and Medium Industries Equity Investment Scheme (SMIEIS) designed by the federal government of Nigeria in 2001, is also an attempt at expanding the financing spectrum for SMEs in Nigeria.

Types of Loan Facilities Granted

However, it is common knowledge that getting financial support from commercial banks has been grossly inadequate for budding indigenous entrepreneurs and even for those who have been in the manufacturing business for a long term. Three types of credit are usually required by small scale enterprises. They include:

1. Short Term Loan: This type of credit is used to finance yearly operation until the product or proceeds from the industry are sold. The amount which is involved in this type of credit is usually small but lack of this type of credit is most accurately felt by small scale entrepreneurs who have little or no saving upon which to withdraw as they are mostly beginners.

2. Medium Term Loan: This type of loan is for more than one year maturity period but not exceeding three to five years. This loan is mostly required for acquisition of inexpensive equipment with relatively short life span.

3. Long Term Loan: This type of credit is necessary for acquisition of major industrial machines, improvement in industrial equipment, building and land: It is a type of loan that the maturity period is for quite a longer duration.

Benefits of Small Scale Enterprises

According to Ojo (1992) the benefits of small scale industry include:

• Stimulation of indigenous entrepreneurship.

• Greater employment creation per unit of capital invested.

• Development of local technology.

• Enhancement of regional economic balance through industrial dispersal.

• Production of intermediate products for use in large scale enterprises.

• Facilitation of managerial training for unskilled than large enterprises at making specialized goods such as embroidery. Mobilization and utilization of demos tic savings

The Role of Banking Sector in Financing SMEs

The banking sector- specifically commercial banks and specialized banks- have several ways to get involved in SMEs finance, ranging from the creation or participation in SMEs finance investment funds, to the creation of a special unit for financing SMEs within the bank. Banking Sector services provided to SMEs, take various from, such as:

• Short term loans compatible with SMEs business and income patterns

• Repeated loans, where full repayment of one loan brings access to another, and where the size of the loan depends on the client’s cash flow

• Very small loans or bank overdraft facilities are also appropriate for meeting the day-to-day financial requirements of small businesses

• Factoring and invoice discounting, asset finance (including commercial mortgages), and equity finance, all being within the framework of a customer-friendly approach. In providing all these services, it is recommended that banks take into consideration

• That outlet is located close to entrepreneurs.

• To use extremely simple loan applications.

• To limit the time between application and disbursement to a few days

• As well as to develop a public image of being approachable to low-income people.

Development strategists have advocated the progressive use of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to accelerate the pace of economic growth especially in the developing countries of the world. Most African countries are basically agrarian societies with the majority of the populace engaging in agro-related activities such as farming, livestock rearing, agro forestry and fishing. With little capital to invest, it seems obvious that the process of industrialization should be based on the development of the SMEs to link agricultural production with manufacturing activities. This requires specific incentives to assist in the development of the SMEs sub-sector, which include among others easy accessibility to credit, provision of infrastructural facilities, industrial extension services and development of production capacity based on locally developed or adapted technology and locally designed equipment and spares. The need to promote a vibrant industrial sector has continued to be a major concern of most governments worldwide especially the developing countries like Nigeria. The reasons for this are centered on the prospects that a developed industrial sector will boost manufacturing production, increase employment generation and efficiency in the sector. Similarly, modern manufacturing processes are characterized by high technological innovations, the development of managerial and entrepreneurial talents and improvement in technical skills which normally promote productivity and better living conditions of the people. The effect of this is that productivity level will be enhanced, a sustainable level of economic growth will be achieved with the prospect of economic diversification and increased exports. The economy will have the potential of being competitive in the global market (Osotimehin et al., 2012)

In recognition of these potential role of the sector, successive governments in Nigeria have continued to articulate policy measures and programs to achieve industrial growth and development, including direct participation, alone or jointly with the private sector, interest groups, assistance from external agencies, provision of industrial incentives and adequate finance as stated in the 1988 industrial policy of Nigeria. However, the poor performance of the industrial sector, especially when emphasis was on medium and large scale enterprises in the course of implementing the import substitution strategy of the Nigerian government, led to the renewed emphasis or focus on the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as the driving force in the industrial sector. The Small and Medium Enterprises play a critical role in both developing and developed countries.

Stiglitz and Marilou argued that the East Asian countries miracle was partly as a result of a vibrant SMEs sub-sector, which triggered the up-surge in exports and subsequent development of the industrial sector. For example, the New Industrialized Countries (NICs) like Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia and China among others, were able to achieve economic growth through the activities of SMEs which later contributed to the transformation of the Large-Scale enterprises. The Republic of China over the years, despite her large population, has been able to generate employment and income for her teeming population through the activities of the SMEs.

The importance of SMEs sub-sector cannot be overemphasized. The sub-sector contributes significantly in achieving various socioeconomic objectives, which include employment generation, contribution to national output and exports, fostering new entrepreneurship and providing a foundation for the industrial base of the economy. In low income countries with Gross National Product (GNP) per capita of between US$100 and US$500, SMEs account for over 60 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 70 percent of total employment; in middle income countries, the SMEs produced close to 70 percent of GDP and 95 percent of total employment; and in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, SMEs constitute the majority of firms and contribute over 55 percent of GDP and 65 percent of total employment. In most developed countries, efforts to support SMEs growth are over a century and have helped to create an enabling environment for their operations.

The Lifecycle Approach

This approach according to Weston and Brigham was conceived around the platform of speedy growth and poor access to capital market. SMEs are perceived to be starting out by exploring only the owners’ resources. Whether or not the firms could make it subsequently, the threat of insufficient capital would later surface, and then the tendency to resort to other sources of funds would emerge. The dynamic small firm prefer to choose between curtailing its growth to keep in line with its minimally generated funds, get an expensive stock market quotation, or desire an almost impossible volume venture capital according to Weston, J. and E. Brigham, Mgt Finance, Hindgale: Dryden Press, 1981. For the purpose of this study, The study population is made up of all selected small scale businesses owners in Ado-Odo, Ota numbering into over 300 registered small business. However, only few of these many small and medium scale enterprises were sampled among them.

Results

Test of Hypotheses

Hypothesis One

H0: There is no significant relationship between policies formulation and implementations in business organizations in Nigeria.

H1: There is a significant relationship between policies formulation and implementations in business organizations in Nigeria.

To test these hypotheses, responses to items 4 and 14 in the questionnaires as analyzed above in Table 1.

| Table 1 Contingency Table One | ||

| Table | Item 4 | Item 14 |

| Strongly Agreed | 17 | 22 |

| Agreed | 22 | 28 |

| Undecided | 5 | 1 |

| Disagreed | 19 | 13 |

| Strongly Disagreed | 7 | 6 |

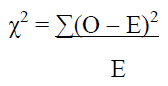

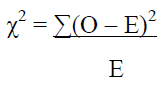

From the formula:

Where, χ2 = Chi- Square O = Observed Value/Orchal data E = Expected Value

The Level of Significance is taken to be 5% or confidence interval of 0.05. Policies formulations and implementations in business organizations in Nigeria, Using Linkert’s scale of 1 to 5 to multiply the responses then, we have the table 2 below.

| Table 2 Contingency Table Two | |||

| Table | Item 4 | Item 14 | Total |

| Strongly Agreed | 85 | 110 | 195 |

| Agreed | 88 | 112 | 200 |

| Undecided | 15 | 5 | 20 |

| Disagreed | 38 | 26 | 64 |

| Strongly Disagreed | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Total | 233 | 259 | 492 |

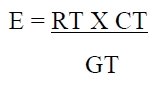

Expected Frequency value is calculated thus;

For correspondent observed cell value

χ Calculated = 12.08

Degree of freedom = (c - 1) (r - 1)

= (2 - 1) (5 - 1)

= (1) (4)

= 4

Level of significance = 0.05 or 5%

χ tabulated = 9.488 approximately 9.49

From the above, the χ Calculated value is 12.08 and the χ Tabulated value is 9.49. From the decision criteria, that is accept H1 (Alternative) hypotheses if the calculated chi square is greater that the tabulated chi square otherwise accept H0 (Null) hypotheses. Given that the calculated chi square is greater than the tabulated chi square, we therefore accept the alternative hypothesis and reject the null hypothesis that there is a significant relationship between policies formulation and implementations in business organizations in Nigeria. This is in line with Barrett and Fudge (2005) whose work revealed that formulating policies is nothing but a paper work if modalities are not set to implement the policies. To the duo, policies implementation is basically dependent on the following as revealed by this research work Table 3.

| Table 3 Contingency Table Three | |||||

| Cell | O | E | O – E | (O – E)2 | (O – E)2/E |

| 1.1 | 85 | 92.35 | -7.35 | 54.02 | 0.59 |

| 1.2 | 110 | 102.65 | 7.35 | 54.02 | 0.53 |

| 2.1 | 88 | 94.72 | -6.72 | 45.16 | 0.48 |

| 2.2 | 112 | 105.28 | 6.72 | 45.16 | 0.43 |

| 3.1 | 15 | 9.47 | 5.53 | 30.58 | 3.23 |

| 3.2 | 5 | 10.53 | -5.53 | 30.58 | 2.90 |

| 4.1 | 38 | 30.31 | 7.69 | 59.14 | 1.95 |

| 4.2 | 26 | 33.69 | -7.69 | 59.14 | 1.76 |

| 5.1 | 7 | 6.16 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.11 |

| 5.2 | 6 | 6.84 | -0.84 | 0.71 | 0.10 |

| χ Calculated | 12.08 | ||||

1. Knowing what to do.

2. The availability of the required resources.

3. The ability to marshal and control these resources to achieve the desired end.

4. If others are to carry out the task, communicating what is wanted and controlling their performance

Hypothesis Two

H0: There is no significant relationship between policies procedures, compliance and implementations in business organizations in Nigeria.

H1: There is a significant relationship between policies procedures, compliance and implementations in business organizations in Nigeria.

To test these hypotheses, responses to items 13 and 14 in the questionnaires as analyzed above Table 4.

| Table 4 Contingency Table Four | ||

| Table | Item 13 | Item 14 |

| Strongly Agreed | 16 | 22 |

| Agreed | 29 | 28 |

| Undecided | 2 | 1 |

| Disagreed | 15 | 13 |

| Strongly Disagreed | 8 | 6 |

From the formula:

Where, χ2 = Chi- Square O = Observed Value/Orchal data E = Expected Value

The Level of Significance is taken to be 5% or confidence interval of 0.05. Policies formulation and implementation in business organization in Nigeria. Using Linkert’s scale of 1 to 5 to multiply the responses then, we have the table 5 below.

| Table 5 Contingency Table Five | |||

| Table | Item 13 | Item 14 | Total |

| Strongly Agreed | 80 | 110 | 190 |

| Agreed | 116 | 112 | 228 |

| Undecided | 6 | 3 | 11 |

| Disagreed | 30 | 26 | 56 |

| Strongly Disagreed | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Total | 240 | 257 | 497 |

Expected Frequency value is calculated thus;

For correspondent observed cell value

χ Calculated = 4.76

Degree of freedom = (c - 1) (r - 1)

= (2 - 1) (5 - 1)

= (1) (4)

= 4

Level of significance = 0.05 or 5%

χ tabulated = 9.488 approximately 9.49

From the above, the χ Calculated value is 4.76 and the χ Tabulated value is 9.49. From the decision criteria, that is accept H1 (Alternative) hypotheses if the calculated chi square is greater that the tabulated chi square otherwise accept H0 (Null) hypotheses. Given that the tabulated chi square is greater than the calculated chi square, we therefore accept the null hypothesis and reject the alternative hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between policies procedures, compliance and implementations in business organizations in Nigeria. As odd that the result of the analysis may look, the result is not new that what is entailed in the developing and developed world is not obtainable here in Nigeria. Regarding theis type of results, Nnamdi (2001) noted that development policies has, in contemporary times, assumed complex and sophisticated dimension that require highly skilled and experienced bureaucrats for their effective implementation. It is worthy of note that the inadequacy of personnel, particularly as it relates to expertise and skilled manpower, results in part, from the personnel recruitment policies into the Nigerian public bureaucracy which are essentially based on non-bureaucratic criteria such as the state of origin or ethnic group against objectively measurable criteria like qualification and professional competence (Amucheazi, 1980; Anikeze, 2011). The application of the principle, popularly known as Quota System or Federal Character results by putting people in job positions where they do not have the basic competencies and skill ultimately, is affecting the ability of the Nigerian public bureaucracy to effectively implement policies Table 6.

| Table 6 Contingency Table Six | |||||

| Cell | O | E | O – E | (O – E)2 | (O – E)2/E |

| 1.1 | 80 | 91.75 | -11.75 | 138.06 | 1.50 |

| 1.2 | 110 | 98.25 | 11.75 | 138.06 | 1.41 |

| 2.1 | 116 | 110.10 | 5.90 | 34.81 | 0.32 |

| 2.2 | 112 | 117.90 | -5.90 | 34.81 | 0.30 |

| 3.1 | 6 | 5.31 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.09 |

| 3.2 | 5 | 5.69 | -0.69 | 0.48 | 0.08 |

| 4.1 | 30 | 27.04 | 2.96 | 8.76 | 0.32 |

| 4.2 | 26 | 28.96 | -2.96 | 8.76 | 0.30 |

| 5.1 | 8 | 6.76 | 1.24 | 1.54 | 0.23 |

| 5.2 | 6 | 7.24 | -1.24 | 1.54 | 0.21 |

| χ Calculated | 4.76 | ||||

Conclusion

This study has made various relevant data available regarding the subject topic.

• For effective policy formulations, businesses must be abreast of what is going on in there environment both internal and external and for policy implementations, all hands must be on deck to see to it that procedures for implementations are reviewed at every stages of the implementation process

• In terms of compliance to procedures, competent hands especially the professionals should be allowed to work on policies that required professionals such that rhe implementation process could not only be effective but also help achieve the goals and the objectives of the organization.

• Lack of monitoring teams, review committees and other bodies that are concern with the effective implementation of policies and procedures in the Nigerian business sector.

Recommendations

Having carefully analysed the central topic of this research work, the following recommendations were made:

a. That companies who find it difficult to comply with the recommended policies of its regulatory body should either go out of business or put in all modalities for the effective implementations of such policies to continually be in business.

b. The staff and customers alike should also be carried along with the internal policies formulations such that their contributions could enhance their adherence to the formulated policies especially when they are done with staff and customers interest at heart.

c. The relevant strategy and synergy should be put in place to aids effective policies and procedure implementations in the Nigeria business sector.

Finally, it is the hope of this researcher that these suggestions will go a long way at reducing the problems associated with the implementation of policies and procedures in the Nigeria business sector as it was seen in this study that implementations of policies in the banking sector has indeed help in the checking the excesses of the management of those banks thus, giving a little sanity and reliability to the Nigerian banking industry.

References

Aernold, R. (1998). Round table discussion on recommendations for best practice in financial intermediaries for SMEs. In Final Report of Expert Meeting on Best Practice in Financing SMEs. United Nations/ECE, Geneva, Switzerland.

Afonja, A. A. (1999). Entrepreneurship Education and Enterprise Culture: Lessons from other Countries”, Paper presented an National Conference on Entrepreneurship Education in Nigeria Tertiary Institutions, Abuja, Nigeria, March 30-April 1, 1999.

Akingunola, R. O. (2011). Small and medium scale enterprises and economic growth in Nigeria: An assessment of financing options. Pakistan journal of business and economic review, 2(1).

Aremu, M. A. (2004). Small scale enterprises: Panacea to poverty problem in Nigeria. Journal of Enterprises Development, 1(1), 1-8.

Aremu, M. A., & Adeyemi, S. L. (2011). Small and medium scale enterprises as a survival strategy for employment generation in Nigeria. Journal of sustainable development, 4(1), 200.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ayeni-Agbaje, A. R., & Osho, A. E. (2015). Commercial banks role in financing small scale industries in Nigeria (A study of first bank, ado-ekiti, ekiti state). European Journal of Accounting. Auditing and Finance Research, 3(8), 52-69.

Etim, E. O. (2010). Promoting small and medium scale enterprises in nigeria: a panacea for realization of financial systems strategy (fss) 2020. International Journal of Economic Development Research and Investment, 1(2), 3.

Evbuomwan, G. O., Ikpi, A. E., Okoruwa, V. O., & Akinyosoye, V. O. (2012). Preferences of micro, small and medium scale enterprises to financial products in Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development, 1(4), 80-98.

Gujarati, D. N. (2003). Basic Econometrics, 4th edition, New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Gunu, U. (2004). Small scale enterprises in Nigeria: Their start up, characteristics, sources of finance and importance. Ilorin Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 9(1), 36-43.

Imafidon, K., & Itoya, J. (2014). An analysis of the contribution of commercial banks to small scale enterprises on the growth of the Nigeria economy. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(9).

Osotimehin, K. O., Jegede, C. A., Akinlabi, B. H., & Olajide, O. T. (2012). An evaluation of the challenges and prospects of micro and small scale enterprises development in Nigeria. American international journal of contemporary research, 2(4), 174-185.

Rasak, B. (2012). Small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs): A panacea for economic growth in Nigeria. Journal of Management and Corporate Governance, 4(6), 86-98.

Udechukwu, F. N. (2003). CBN Seminar on Small and Medium Industries Equity

Received: 02-Mar-2024, Manuscript No. jmids-24-14706; Editor assigned: 06-Mar-2024, Pre QC No. jmids-24-14706(PQ); Reviewed: 19- Mar-2024, QC No. jmids-24-14706; Published: 28-Mar-2024