Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 6

Impact of Global Financial Crisis 2008-09 and Global Oil Prices on the Economic Growth of Asean Countries: An Evidence from Driscoll-Kraay Standard Errors Regression

Ali Burhan Khan, Finance and Banking University Utara Malaysia

Thathira Siriphan, Songkhla Rajabhat University

Rarina Mookda, Songkhla Rajabhat University

Tunwarat Kongnun, Pibulsongkram Rajabhat University

Sudarat Rattanapong, Pibulsongkram Rajabhat University

Yusraw Omanee, Phuket Rajabhat University

Pinsuda Thonghom, University Utara Malaysia

Citation Information: Khan, A.B., Siriphan, T., Mookda, R., Kongnun, T., Rattanapong, S., Omanee, Y., & Thonghom, P. (2021). Impact of Global Financial Crisis 2008-09 and Global Oil Prices on the Economic Growth of Asean Countries: An Evidence from Driscoll-Kraay Standard Errors Regression. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 25(6), 1-11.

Abstract

The origin of the global financial crisis was advanced economies, but it put severe consequences on emerging economies. Therefore, in this paper, we attempt to analyze the impact of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) 2008-09 on the economic growth of ASEAN countries. Besides, the current study also captured the impact of global oil prices on economic growth. An empirical investigation was performed with the help of Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression. The study sample consists of 5-ASEAN countries (Indonesia, Malasia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand) and covers the period 2001-2019. According to the results, GFC proved to be harmful to the economic growth of selected ASEAN countries. Notwithstanding, change in oil prices does not explain the economic growth. The current study has implications for policymakers of ASEAN that by considering the negative consequences of GFC, they should adopt an effective policy to tackle any such type of crisis in the future.

Keywords

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Exports, Global Financial Crisis, Global Stock Index Performance, Oil Prices.

Introduction

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC), which resulted from the US subprime crisis in 2007, created a lack of trust among investors and dried up the global market (Merrouche & Nier, 2010). Due to such development, GFC translated into a liquidity crisis (Kawai, 2009). In 2008, this crisis spill-over the global economy and resulted in regulatory failures in many countries. The impact of GFC was felt by the whole world (Trihadmini & Falianty, 2020), and its consequences are still alive. These consequences also resulted in the sudden deterioration of wealth (Aamir & Shah, 2018).

Even the group of ASEAN-4 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand) is homogeneous, the impact of GFC on them was not uniform (Sangsubhan & Basri, 2012). There are various reasons for such varying effects. First, more open economies such as Malaysia and Thailand faced more significant trade shocks. Second, in Indonesia and the Philippines, countercyclical fiscal stimulus was more powerful and sustained for a more extended time. Third, idiosyncratic factors pushed output down in Thailand and up in extended time. Third, idiosyncratic factors pushed output down in Thailand and up in Indonesia. For Thailand, these factors were natural disasters and political instability. In contrast, in Indonesia, these factors were fortuitously timed election spending and investment-friendly structural reforms. According to International Monetary Fund (2010), the total output of ASEAN-5 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam) plummeted to 1.7 percent in 2009 from 4.5 percent in 2008. Among these countries, Indonesia’s economy showed much resilience against GFC and kept growing at around 4.5 percent during 2009. The credit goes to less dependence on trade and solid domestic demand.

Before the GFC, ASEAN nations grew at an annual rate of about 5 percent. As the GFC start, Thailand and Malaysia became the principal victim of GFC by having -7.2 percent and -6.4 percent change in real GDP from the third quarter of 2008 to the first quarter of 2009. The growth rate of the Philippines declined for just one quarter, whereas Indonesia’s did not face any decline. After the GFC, the growth rate difference among ASEAN countries become wider. As opposed to Indonesia’s 6.5 percent growth rate, Thailand just attained a 3 percent. By 2012, the Philippines managed to sustain pre GFC growth rate. Finally, Thailand faced the slowest growth rate after GFC. the overall trade growth of ASEAN nations during post covid period was below than expected (Kabir et al., 2018).

During the post GFC period, various factors played a crucial role in such wider difference in growth among ASEAN countries. The main factor was the size of external shocks (Isnawangsih et al., 2013). These shocks and magnitude of trade were different for different ASEAN countries. The transmission of these shocks to the domestic economy depended on the degree of financial development, the composition of exports, degree of trade openness, corporate and household balance sheets, and the banking sector’s strength. Notwithstanding, the role played by policymakers during the post-GFC period was also a matter of great importance. Notwithstanding, the ASEAN countries with more robust monetary and fiscal policies performed better after GFC.

Energy plays a vital role in the global economic system. Although there is an increase in debate related to the use of alternate renewable sources such as solar, water, and nuclear, oil is still a significant energy source for the global economy (Abdelsalam, 2020). Change in oil prices could have implications for oil exporting and importing countries. For the former category, it determines the production cost, and for later, it is a significant source of revenue for a country (Abdelsalam, 2020). For oil-exporting countries, an increase in oil prices can increase their available funding for development projects. Therefore, these countries’ fiscal and monetary policies are influenced by oil prices (Saddiqui et al., 2018).

Fluctuation in oil prices can also impact transportation cost, production cost and heating bills (Abdelsalam, 2020). More specifically, it affects the prices of goods made with petroleum products. Oil prices spikes also create uncertainty about the future; as a result, households and firms delay the purchase and investment decisions. An increase in oil prices also shifts labour and capital from the energy-intensive sector to a non-energy intensive sector. Due to these reasons, an increase in oil prices significantly reduces economic growth (Sill, 2007). During the last two decades, oil prices exhibited greater swings. The fluctuations of oil prices were due to shortage or oversupply of oil in the global market. The changes in oil supply to the global market were motivated by diverse economic and political factors. Such changes also created oil-price volatility and shocks.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study in previous literature addressed the impact of the Global Financial Crisis 2008-09 and global oil prices on the economic growth of ASEAN countries. Therefore, this study empirically fills this gap. Additionally, current research relies on the most advanced and robust technique, named Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression, to analyze such impact. In line with the identified empirical gap, this research contributes to the ASEAN region’s economy by exploring the role played by the Global Financial Crisis 2008-09 and global oil prices.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the relevant literature review. Section 3 explains the research methodology. Section 4 provides a discussion of the results. The last section concludes the research by highlighting major findings and providing policy implications.

Literature Review

Global Financial Crisis (GFC)

The economic or financial crisis could have serious consequence for investors. Therefore, this topic has attracted academic researchers’ considerable attention (Kotkatvuori-Örnberg et al., 2013). For instance, the crash of 1987 (Forbes & Rigobon, 2002), the Latin American Crisis of 1994-1995 (Fratzscher, 1998), Asian crises of 1997 (Berg & Pattillo, 1999; Fratzscher, 1998; McKenzie, 2007), Brazilian crisis 1997–1998 (Kenourgios et al., 2011), Russian crisis 1998 (Pinto & Ulatov, 2010), technology bubble collapse of 2000 (Perez, 2009), the terrorist attacks of 9.11 (Hon et al., 2004) and Brazilian crisis 2002 (Grigera et al., 2019) have been widely investigated. Besides these crises, the Global financial crisis was the worst (Wang et al., 2017) and the second major hit to the global economy after the 1930’s great depression (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2020). More recently, studies have addressed the relationship of GFC 2008-09 with economic growth (R. Ahmad et al., 2016; Blundell-Wignall & Roulet, 2014; Dao, 2017; Raza & Abd Karim, 2017; Schoenbaum, 2012; Tabata, 2009).

At the start of October 2007, the equity market of the world was standing at an all-time high by having a market capitalization of more than USD 51 trillion. The things which happened in the upcoming 17 months proved to be the most extensive destruction of market capitalization in history. By February 2009, the global equity market capitalization was standing at about USD 22 trillion. This drop was more than 56 percent and was equivalent to 50 percent of the GDP of the world for 2007. At the time of the GFC, the whole economy of the world was facing a fear of total collapse (Merrouche & Nier, 2010).

On September 15, 2008, as the Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, everything fell rapidly (Bartram & Bodnar, 2009), and a severe global financial crisis took place (Chen & Yeh, 2021). Afterwards, this crisis started to control the rest of the world (Grout & Zalewska, 2016). The intensity of this crisis was so hard as it left no place for an equity investor to hide (Bartram & Bodnar, 2009). Moreover, a Study by Bekhet and Yasmin (2014) in the market of Malaysia reported a significant negative impact of GFC on export and economic growth. Accordingly, Chen and Yeh (2021) established a negative relationship between the global financial crisis of 2008 with the financial market.In the context of developing countries, Ahmad et al. (2016) concluded that GFC reduced the positive effect of stock market development and banking sector development on economic growth in selected developing countries. In addition, Voskoboynikov (2017) reported that labour productivity growth declined after the global financial crisis period in Russia.

Oil Prices

Oil is a significant source to fulfil energy demand since the last century (Brini et al., 2016), specifically after World War II (Basnet & Upadhyaya, 2015). In 2008, it covered one-third of the total energy needs of the world. Due to such heavy dependence on oil, most of the world’s countries are affected by crude oil prices movement; either consumers, producers, or both (Brini et al., 2016).

Oil price is an essential factor that influences domestic economies (Cuñado & Gracia, 2003; Hamilton, 1983, 2011). It was stated by Razmi et al. (2016) that oil prices during the period of the global financial crisis significantly impacted the ASEAN countries. A study by Cuñado & Gracia (2003) found the short run asymmetric impact of oil prices on economic growth in European countries. Inline, Hamilton (2011) also found the non-linear relationship between oil prices and GDP growth rate. According to Hamilton (1983), oil price shocks were a contributer to the US recession before 1972. They also claimed that an increase in energy prices could also impact the post-OPEC macroeconomic performance. Abdelsalam (2020) research found that an increase in oil prices positively impacts oil exporting countries. On the contrary, the impact on oil-importing countries was negative. Their sample consisted of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries over 1970–2018.

Control Variables

Global Index Performance (measured by MSCI global index return) and exports were selected as control variables in this study. The change in global stock prices causes uncertainty for the global economic policy (Hall & Bentley, 2018). Such uncertainty can impact the economic growth of a country. As reported by Harvey (1991), the world returns significantly influenced the economy of Japan. A similar conclusion was also drawn by Møller and Rangvid (2018). Their sample consists of 12 developed economies and covered the period 1970-2013. Additionally, MSCI Barra Research (2010) Found that trends in the global equity index and GDP follow the same direction in the long term.

Exports are the engine of the economic growth of a country. In addition, export-led economic growth is becoming the focus of theoretical and empirical work (Pan & Nguyen, 2018). Furthermore, the relationship between export and economic growth also has central importance in development policy (Ahmad & Harnhirun, 1996). An increase in exports can be a positive contributor to GDP as it is an essential component of GDP (Pan & Nguyen, 2018).

ASEAN, a regional security concerned organization in the past, is now becoming economic growth-oriented. It is also realizing that it can promote regional development with the help of exports and global trade. Therefore, ASEAN countries continuously exploring ways to increase their exports. It was recommended by Pan and Nguyen (2018) that to promote economic development, ASEAN countries should get benefit by increasing their exports to western industrialized nations.

The economic success of Asian Newly Industrializing Countries (NICs) encouraged other Asian countries to adopt aggressive export promotion strategies, and some countries managed to achieve it (Ahmad & Harnhirun, 1996). The 5-ASEAN countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand), selected in this study, set a good example of economic success by finding their reasonable share in the global economy. Although these countries’ economies are export-based, there is still a difference in the export commodity of each country. For instance, Singapore mainly exports the manufactured goods. Indonesia’s export is based on primary commodities such as rubber, petroleum and plywood. The main exports of Thailand are rice, electronic parts and automobiles. Malaysia is an exporter of palm oil, petroleum, electronics components and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). The Philippines is the main exporter of labour and heavily depends on the remittances sent by the labour working abroad. In the ASEAN, Furuoka (2009) study reported the significant impact of exports on selected ASEAN countries. On the contrary, Ahmad and Harnhirun (1996) did not find any such relationship.

Research Methodology

Data and Measurement

In this study, yearly data of selected variables was collected from 2001-2019. Economic growth was chosen as a dependent variable, global financial crisis and global oil prices as independent variables whereas, global stock index performance and exports were taken as control variables. Each variable consists of 95 observations. The sample of this study consists of ASEAN-5 countries, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. The same sample of the ASEAN region was also targeted by Furuoka (2009) and Ahmad & Harnhirun (1996) study while analyzing the relationship between exports and economic growth. The summary view of selected variables, measurement, support of previous literature and data sources is provided in Table 1.

| Table 1 Selected Variables’ Names, Notations, Measurement and Source | ||||

| Variable | Variable Type | Measurement | Literature Support | Source |

| Economic Growth (EG) | Dependent | GDP growth (annual %) | (Nkusu, 2011; Staehr & Uusküla, 2021; Umar & Sun, 2018) | Bloomberg Data Terminal |

| Global Financial Crisis (GFC) | Independent | Dummy variable “1” for crisis period 2008-09, “0” otherwise | Studies considered 2008-09 as Global Financial Crisis period include: Isnawangsih et al. (2013); Bartram and Bodnar (2009), and Kotkatvuori-Örnberg et al. (2013) | Bloomberg Data Terminal |

| Global Oil Prices (GOP) | Independent | Change in Brent crude oil prices | (Novotný, 2012) | Bloomberg Data Terminal |

| Global Stock Index Performance (GSI) | Control | MSCI global index return | (Assefa & Mollick, 2014; Graham et al., 2016; Khamlichi et al., 2014) | Bloomberg Data Terminal |

| Exports (EXP) | Control | Nominal Value (percentage) | (Celebi & Hönig, 2019) | Bloomberg Data Terminal |

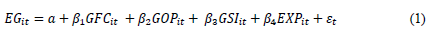

The econometric form of relationship between independent, dependent and control variables is reported in equation 1:

Where EG represents economic growth, GFC stands for the global financial crisis, GOP exhibits global oil prices, GSI indicates global stock index performance, and EXP shows exports.

For empirical investigation, current research adopted Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression approach developed by (Driscoll & Kraay, 1998). This approach is a nonparametric covariance matrix estimator. This estimator produces such heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation-consistent standard errors which are robust to common forms of spatial and temporal dependence. The original contribution of Driscoll and Kraay considers only balanced panels (Hoechle, 2007).

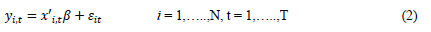

The use of robust standard errors is common in case some assumptions of the underlying regression model are violated. In this scenario, the application of robust standard errors also ensures the validity of statistical inference. Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression approach removes the inefficiencies of other large-T consistent covariance matrix estimators like the PCSE approach and Parks Kmenta. These estimators are inappropriate when cross-sectional dimension N becomes larger (Hoechle, 2007). Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression is an advanced and robust technique for heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation and cross-sectional dependence. This technique is widely applied by previous research (Al-Gamrh et al., 2020; Baloch et al., 2019; Erden et al., 2015; Khasawneh & Dasouqi, 2017; Pazienza, 2015). The equation of the current study by using Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression is shown in equation 2:

In the above equation, yi,t is the dependent variable (Economic Growth) and a scaler. xi,t represents the independent (global financial crisis and global oil prices) and control variables (global stock index performance and exports).

Results and Interpretations

The descriptive statistics and correlation are reported in the Table A1 and A2 of the appendix. The results of Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression are presented in Table 2.

| Table 2 Driscoll-Kraay Standard Errors Regression Results | |||

| Variable | Coefficient | Drisc/Kraay Standard Error | P-value |

| C | 7.841 | 2.990 | 0.017 |

| GFC | -3.061*** | .992 | 0.006 |

| OP | -.930 | .959 | 0.345 |

| GSI | -1.819 | 2.264 | 0.432 |

| EXP | .058** | .025 | 0.034 |

** Significant at the 0.05 level

*** Significant at the 0.01 level

According to the results reported in Table 2, the highly significant and negative impact (at the level of 0.05) of GFC on the economic growth of ASEAN is observed. At the same time, oil prices do not influence the economic growth of selected ASEAN countries. In terms of control variables, exports are significant positive contributors to ASEAN nations’ economic growth.

The negative impact of GFC on the ASEAN countries indicate that as the GFC impacted the whole world (Aamir & Shah, 2018; Trihadmini & Falianty, 2020), the ASEAN region is not an exception. Similar founding was reported in the case of the Malaysian economy, where GFC put its significant and negative impact on economic growth (Bekhet & Yasmin, 2014). The spill-over effect of the global financial crisis also had a damaging effect on ASEAN economic growth. As it was stated by Blanchard et al. (2010), when the GFC intensified, it transmitted to Europe, than in 2008, it took control of emerging markets. These results also reflect the claim of Isnawangsih et al. (2013) that the distortion due to GFC put ASEAN country’s development on different trajectories. Such trajectories were almost the same before the GFC period.

In terms of control variables, a significant and positive impact of exports on ASEAN economic growth was found in this study. These results are supported by Furuoka (2009) research, which reported the significant influence on export on economic growth. This study’s findings are also consistent with (Pan & Nguyen, 2018) claim that the ASEAN region can increase regional development with the increase in exports. It is because the nature of the ASEAN economy is export-based (Furuoka, 2009).

Conclusion

This paper examines the effect of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) 2008-09 and global oil prices on the economic growth of 5-ASEAN countries, including Indonesia, Malasia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. This research relied on an advanced and robust econometric technique named; Driscoll-Kraay standard errors regression for empirical investigation. According to the results, GFC was a significant negative contributor to the economic growth of ASEAN countries. In contrast, economic growth remains unaffected by the change in oil prices. Moreover, in the context of control variables, an increase in exports proved to be favourable for the economic growth of the ASEAN region. In terms of future implications of this research, it can be used as a decision-support tool for the policymakers of ASEAN countries while considering the impact of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) on the ASEAN economy.

Appendix

| Table A1 Descriptive Statistics | |||||

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| EG | 95 | 4.906 | 2.333 | -1.513 | 14.525 |

| GFC | 95 | - | - | 0 | 1 |

| OP | 95 | 64.133 | 27.785 | 19.9 | 111.11 |

| GSI | 95 | 1439.578 | 405.973 | 792.21 | 2358.47 |

| EXP | 95 | 5.795 | 14.919 | -40.3 | 50.04 |

| Table A2 Multicollinearity Results | ||||||

| Variable | GFC | OP | GIP | EXP | VIF | Tolerance Factor (1/VIF) |

| GFC | 1 | 1.08 | 0.924 | |||

| OP | -0.017 | 1 | 1.85 | 0.541 | ||

| GSI | -0.242 | 0.439 | 1 | 1.77 | 0.563 | |

| EXP | -0.055 | 0.676 | 0.626 | 1 | 2.46 | 0.405 |

References

- Aamir, M., & Shah, S.Z.A. (2018). Determinants of stock market co-movements between Pakistan and Asian emerging economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 11(3), 1–14.

- Abdelsalam, M.A.M. (2020). Oil price fluctuations and economic growth: the case of MENA countries. Review of Economics and Political Science. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/REPS-12-2019-0162

- Ahmad, J., & Harnhirun, S. (1996). Cointegration and causality between exports and economic growth: evidence from the ASEAN countries. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 29, 413–416.

- Ahmad, R., Etudaiye-Muhtar, O.F., Matemilola, B.T., & Bany-Ariffin, A.N. (2016). Financial market development, global financial crisis and economic growth: evidence from developing nations. Portuguese Economic Journal, 15(3), 199–214.

- Al-Gamrh, B., Ismail, K.N.I.K., Ahsan, T., & Alquhaif, A. (2020). Investment opportunities, corporate governance quality, and firm performance in the UAE. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 10(2), 261–276.

- Assefa, T.A., & Mollick, A.V. (2014). African stock market returns and liquidity premia. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 32, 325–342.

- Baloch, M.A., Zhang, J., Iqbal, K., & Iqbal, Z. (2019). The effect of financial development on ecological footprint in BRI countries: evidence from panel data estimation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(6), 6199–6208.

- Bartram, S.M., & Bodnar, G.M. (2009). No place to hide: The global crisis in equity markets in 2008/2009. Journal of International Money and Finance, 28(8), 1246–1292.

- Basnet, H.C., & Upadhyaya, K.P. (2015). Impact of oil price shocks on output, inflation and the real exchange rate: evidence from selected ASEAN countries. Applied Economics, 47(29), 3078–3091.

- Bekhet, H.A., & Yasmin, T. (2014). Assessment of the global financial crisis effects on energy consumption and economic growth in Malaysia: An input–output analysis. International Economics, 140, 49–70.

- Berg, A., & Pattillo, C. (1999). What caused the Asian crises: An early warning system approach. Economic Notes, 28(3), 285–334.

- Blanchard, O.J., Faruqee, H., Das, M., Forbes, K.J., & Tesar, L.L. (2010). The initial impact of the crisis on emerging market countries [with comments and discussion]. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 263–323.

- Blundell-Wignall, A., & Roulet, C. (2014). Capital controls on inflows, the global financial crisis and economic growth: Evidence for emerging economies. OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, 2013(2), 29–42.

- Brini, R., Jemmali, H., & Farroukh, A. (2016). Macroeconomic impacts of oil price shocks on inflation and real exchange rates: evidence from MENA economies. Topics in Middle Eastern and African Economies, 18(2), 170–185.

- Celebi, K., & Hönig, M. (2019). The impact of macroeconomic factors on the German stock market: Evidence for the crisis, pre-and post-crisis periods. International Journal of Financial Studies, 7(18).

- Chen, H.C., & Yeh, C.W. (2021). Global financial crisis and COVID-19: Industrial reactions. Finance Research Letters, 101940.

- Cuñado, J., & Gracia, F.P. de. (2003). Do oil price shocks matter? Evidence for some European countries. Energy Economics, 25(2), 137–154.

- Dao, M.Q. (2017). Determinants of the global financial crisis recovery: an empirical assessment. Journal of Economic Studies, 44(1), 36–46.

- Driscoll, J.C., & Kraay, A.C. (1998). Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(4), 549–560.

- Erden, Z., Klang, D., Sydler, R., & von Krogh, G. (2015). “How can we signal the value of our knowledge?” Knowledge-based peputation and its impact on firm performance in science-based industries. Long Range Planning, 48(4), 252–264.

- Forbes, K.J., & Rigobon, R. (2002). No contagion, only interdependence: measuring stock market comovements. The Journal of Finance, 57(5), 2223–2261.

- Fratzscher, M. (1998). Why are currency crises contagious? A comparison of the Latin American crisis of 1994–1995 and the Asian crisis of 1997–1998. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 134(4), 664–691.

- Furuoka, F. (2009). Exports and economic growth in ASEAN countries: Evidence from panel data analysis. Journal of Applied Economics, 3, 7–16.

- Graham, M., Peltomäki, J., & Piljak, V. (2016). Global economic activity as an explicator of emerging market equity returns. Research in International Business and Finance, 36, 424–435.

- Grigera, J., Webber, J.R., Abilio, L., Antunes, R., Mattos, M.B., Fernandes, S., Nunes, R., Paulani, L., & Purdy, S. (2019). The Long Brazilian Crisis: A Forum. Historical Materialism, 27(2), 59–121.

- Grout, P.A., & Zalewska, A. (2016). Stock market risk in the financial crisis. International Review of Financial Analysis, 46, 326–345.

- Hall, A.M., & Bentley, R.A. (2018). Changes in global equity prices precede changes in global expressions of economic policy uncertainty. The Journal of Behavioral Finance & Economics, 6(1&2), 33–57.

- Hamilton, J.D. (1983). Oil and the macroeconomy since World War II. Journal of Political Economy, 91(2), 228–248.

- Hamilton, J.D. (2011). Nonlinearities and the macroeconomic effects of oil prices. In Macroeconomic dynamics (No. 16186). Cambridge University Press.

- Harvey, C.R. (1991). The world price of covariance risk. The Journal of Finance, 46(1), 111–157.

- Hoechle, D. (2007). Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. The Stata Journal, 7(3), 281–312.

- Hon, M.T., Strauss, J., & Yong, S. (2004). Contagion in financial markets after September 11: myth or reality? Journal of Financial Research, 27(1), 95–114.

- International Monetary Fund. (2010). World Economic Outlook (WEO) - Rebalancing Growth. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/01/

- Isnawangsih, A., Klyuev, M.V., & Zhang, M.L. (2013). The Big Split: Why Did Output Trajectories in the ASEAN-4 Diverge after the Global Financial Crisis? (WP/13/222). International Monetary Fund.

- Kabir, S., Bloch, H., & Salim, R.A. (2018). Global financial crisis and Southeast Asian trade performance: Empirical evidence. Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies, 30(2), 114–144.

- Kawai, M. (2009). Global Financial Crisis and Implications for ASEAN. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Publishing.

- Kenourgios, D., Samitas, A., & Paltalidis, N. (2011). Financial crises and stock market contagion in a multivariate time-varying asymmetric framework. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 21(1), 92–106.

- Khamlichi, A., Sarkar, K., Arouri, M., & Teulon, F. (2014). Are Islamic equity indices more efficient than their conventional counterparts? Evidence from major global index families. Journal of Applied Business Research, 30(4), 1137–1150.

- Khasawneh, A.Y., & Dasouqi, Q.A. (2017). Sales nationality and debt financing impact on firm’s performance and risk. EuroMed Journal of Business, 12(1), 103–126.

- Kotkatvuori-Örnberg, J., Nikkinen, J., & Äijö, J. (2013). Stock market correlations during the financial crisis of 2008–2009: Evidence from 50 equity markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 28, 70–78.

- McKenzie, M.D. (2007). Technical trading rules in emerging markets and the 1997 Asian currency crises. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 43(4), 46–73.

- Merrouche, O., & Nier, E. (2010). What caused the Global Financial Crisis? Evidence on the drivers of financial imbalances 1999–2007 (Working Paper No. 10/65).

- Møller, S.V, & Rangvid, J. (2018). Global economic growth and expected returns around the world: The end-of-the-year effect. Management Science, 64(2), 573–591.

- MSCI Barra Research. (2010). Is There a Link Between GDP Growth and Equity Returns? https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/a134c5d5-dca0-420d-875d-06adb948f578

- Nkusu, M. (2011). Nonperforming loans and macrofinancial vulnerabilities in advanced economies (WP/11/161).

- Novotný, F. (2012). The link between the Brent crude oil price and the US dollar exchange rate. Prague Economic Papers, 21(2), 220–232.

- Pan, M., & Nguyen, H. (2018). Export and growth in ASEAN: does export destination matter? Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies, 11(2), 122–131.

- Pazienza, P. (2015). The relationship between CO2 and Foreign Direct Investment in the agriculture and fishing sector of OECD countries: Evidence and policy considerations. Intelektin? Ekonomika, 9(1), 55–66.

- Perez, C. (2009). The double bubble at the turn of the century: technological roots and structural implications. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(4), 779–805.

- Pinto, B., & Ulatov, S. (2010). Financial globalization and the Russian crisis of 1998 (Working Paper No. 5312).

- Raza, S.A., & Abd Karim, M.Z. (2017). Influence of systemic banking crisis and currency crisis on the relationship of export and economic growth. Journal of Chinese Economic and Foreign Trade Studies, 10(1), 82–110.

- Razmi, F., Azali, M., Chin, L., & Habibullah, M.S. (2016). The role of monetary transmission channels in transmitting oil price shocks to prices in ASEAN-4 countries during pre-and post-global financial crisis. Energy, 101, 581–591.

- Reserve Bank of Australia. (2020). The Global Financial Crisis. https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/pdf/the-global-financial-crisis.pdf?v=2020-05-27-15-56-21

- Saddiqui, S.A., Jawad, M., Naz, M., & Niazi, G.S.K. (2018). Exchange rate, fiscal policy and international oil prices impact on oil prices in Pakistan: A volatility and granger causality analysis. Review of Innovation and Competitiveness: A Journal of Economic and Social Research, 4(1), 27–46.

- Sangsubhan, K., & Basri, M.C. (2012). Global Financial Crisis and ASEAN: Fiscal Policy Response in the Case of T hailand and I ndonesia. Asian Economic Policy Review, 7(2), 248–269.

- Schoenbaum, T.J. (2012). The age of austerity: The global financial crisis and the return to economic growth. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sill, K. (2007). The macroeconomics of oil shocks. Business Review, 1(1), 21–31.

- Staehr, K., & Uusküla, L. (2021). Macroeconomic and macro-financial factors as leading indicators of non-performing loans. Journal of Economic Studies, 48(3), 720–740.

- Tabata, S. (2009). The impact of global financial crisis on the mechanism of economic growth in Russia. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50(6), 682–698.

- Trihadmini, N., & Falianty, T.A. (2020). Stock market contagion and spillover effects of the Global Financial Crisis on five ASEAN countries. Institutions and Economies, 12(3), 91–119.

- Umar, M., & Sun, G. (2018). Determinants of non-performing loans in Chinese banks. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 12(3), 273–289.

- Voskoboynikov, I.B. (2017). Sources of long run economic growth in Russia before and after the global financial crisis. Russian Journal of Economics, 3(4), 348–365.

- Wang, G.J., Xie, C., Lin, M., & Stanley, H.E. (2017). Stock market contagion during the global financial crisis: A multiscale approach. Finance Research Letters, 22, 163–168.