Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 6

Impact of Branding of Otc Skincare Products on Indian Consumers Market

Nandini Rastogi, NMIMS School of Law

Citation Information: Rastogi, N. (2022). Impact of branding of otc skincare products on indian consumers market. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(6), 1-8.

Abstract

Factors This paper focuses on the impact of the independent variable, Branding of Skincare, on the dependent variable, the Indian Consumer Market. Purpose The purpose of this paper is to prove that some brands greenwash consumers to believe that their product is virtuous and effective by avoiding silicones, preservatives and chemicals, however, they tend to use harsh chemicals and irritants which may cause skin sensitivity instead. This paper strives to elaborate on the facts and evidence that such ingredients are scientifically safe. Research Methodology This paper is a summarization of the most recent literature reviews, consisting of marketing journals and medical journals. The research is qualitative instead of quantitative, and concepts are comprehensively explained. The researcher also uses primary research to find evidence of greenwashing in the Indian consumer market. Findings This paper discusses the evolution of the myths that demonize parabens, silicones and sulphates by citing papers and research that lead to such allegations. Further, this paper discusses how Indian consumers do not cater to their skin needs due to the spread of misinformation by such brands. Research Implications This paper urges dermatologists and cosmetologists with big audiences to verify facts and debunk such myths, so these brands do not profit from false marketing. Additionally, this paper can be used as a multidisciplinary study for further research. Originality This paper is backed up with Scopus indexed and ABDC journals.

Keywords

Skin Care, Branding, Consumer Behaviour.

Introduction

Branding is the process of establishing and moulding a brand in the eyes of consumers to bring meaning to a specific organisation, commodities, or facilities. All brands have their set of goals, visions and missions, and having a consumer market like India gives them a bigger platform to justify and increase the sale of their products.

Skincare is one of the biggest Industries in India and is continuously growing. The two main types of cosmetics are OTC and prescription skincare. OTC skincare is skincare that can be purchased without a prescription and can be sold by brands after being clinically tested. Several Indian firms have made significant inroads into the global markets. Some well-known brands include “Himalaya, Lotus Herbal and Khadi Herbal”. However, some brands “greenwash” their consumers and use labels such as “paraben free, sulphate free, organic” to portray some safe ingredients as unsafe, but end up using harsher ingredients instead.

Brands use influencer marketing to market and sell their products to the followers of the particular influencer. However, in most cases, the consumers do not cater to their skincare needs and use the product because their preferred influencer advertises it. This causes side effects on the skin and consumers are manipulated to think that something is working for them when it is making it worse for them.

This paper talks about the phenomenon of greenwashing used by the brands and how they influence people to buy the product by creating fear in their minds regarding certain ingredients.

Research Objectives

The objectives of this paper are:

1. To understand the concept of greenwashing.

2. To analyse the branding of skincare products and its impact on Indian consumers

3. To prove that all ingredients shunned by brands are not harmful to the skin.

Research Questions

This paper aims to answer the following questions:

1. How do brands convince consumers to buy their products by their labels?

2. How misinformation is spread to the consumers?

3. What are some of the safe ingredients feared by consumers due to false branding?

Research Hypothesis

H0 Branding of skincare products does not influence Indian consumers.

H1 Branding of skincare products influences Indian consumers.

Research Limitations

The limitation faced by the researcher was the content available was either about branding and marketing or about the skincare industry and dermatology. There is a lack of interdisciplinary study involving researchers from business and medical majors, thus the researcher had to study and include both marketing and medical journals to give justice to the topic.

Literature Review

Studied the impact of the dependant variable, pandemic, on the independent variable, purchase and consumption of cosmetics among women of Gurugram, India. The researcher surveyed 159 cosmetic product users of different age groups and found that body care cosmetics like face care and hair care were stocked more than makeup products.(Scieszko et al., 2021) further studied that 33% women of a total of 412 women located in Poland, who invested more time in their skin, noticed little improvement and 14% noticed a huge difference. 76% of dermatologists, cosmetologists and other women with cosmetic education noticed considerable improvement due to more time investment and knowledge.

(Talwar et al., 2020) researched on viral spread of fake news through the honeycomb method. Various brands publish fake news which negatively influences consumers about certain products. When such news goes viral, they end up demonizing some safe products and ingredients, which causes a change in consumer buying behaviour. In various conditions, people are misled by fake comments under reviews. This process of sharing misinformation on online sites is termed “online forgery” studied the fear-mongering around Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS), parabens and preservatives. The ingredients used in cosmetic and skincare products are clinically verified before being launched to the public. The researcher appreciated that the public is proactive in their research, however, it is important that cosmetologists and dermatologists eradicate fear-mongering amongst the public regarding safe ingredients. The brands should explicitly announce that not all chemical substances are harmful, and not all natural substances are good for skin, hair and body. (van der Schyff et al., 2022) studied “green” personal care products where he found that mostly unregulated and unstandardized expressions like “natural, organic, no artificial preservatives” were printed on products to influence consumers to buy the products, even though they contained a higher concentration of much harmful ingredients. This process of false labelling as “natural” is known as “greenwashing”

Findings

On March 11th, 2020, the Pandemic was officially declared which came with a set of rules where people couldn’t leave home due to lockdowns and quarantine (WHO, 2020). Many of them used this time to invest in their well-being, which included healthy food consumption, exploring new hobbies, and taking care of body and skin. During this time, the Indian market noticed a surge in sales of OTC skincare products. The purchase and consumption of makeup decreased by a noticeable percentage, while the purchase pattern of face care and lip care products increased (Gupta & Kala, 2021).

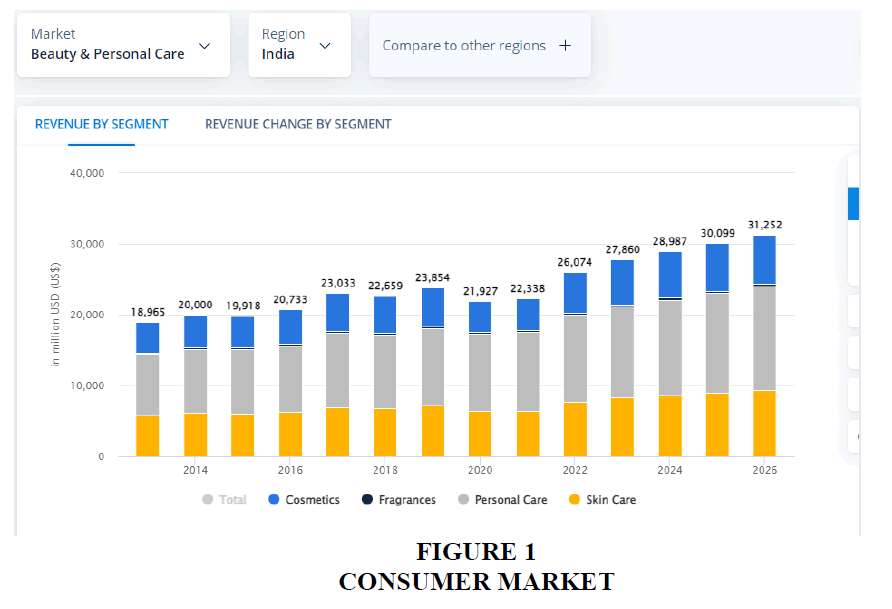

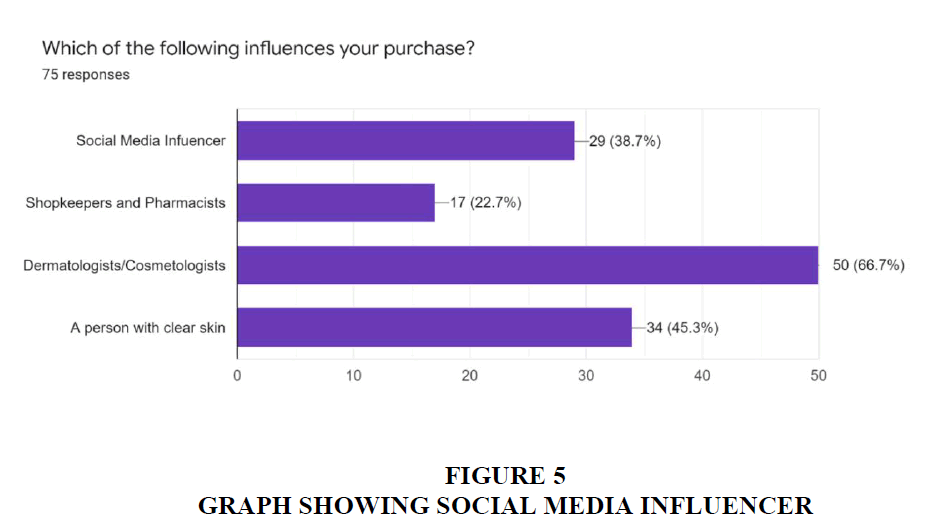

In recent years, beauty and personal care consumption in the Indian market have risen and various new brands have entered the Indian market (Pal et al., 2020). Some brands that have gained comparatively more attention are - Cosrx, True Frog, One Thing, The Formularx, Supergoop, and many more Figures 1-5.

With the increase in the cosmetic market, brands analysed the consumer market and saw an increase in environmentally-woke consumers, which lead to brands greenwashing customers using terms like “natural” and “organic” on their labels, and concealing the much harmful ingredients to increase their sales (Arouri et al., 2021).

In order to prove the certain branding styles of beauty and personal care products, the researcher has conducted primary research via survey method.

Primary Research

Participants’ Data

The researcher conducted primary research which included 75 participants residing in India. 53.3% (40 respondents) were female, while 46.7% (35 respondents) were male. The majority of respondents (77.3%, 58 respondents) were between the age groups 20-30, and 17.3% (13 respondents) belonged to the age group 13-19. Only 4 respondents belonged to the 41+ age group. 70.7% (53 respondents) were doing UG, 21.3% (16 respondents) completed and were in 12th grade, 6.7% (5 respondents) completed PG and only 1.3% (1 respondent) had a PhD.

Survey

Analysis

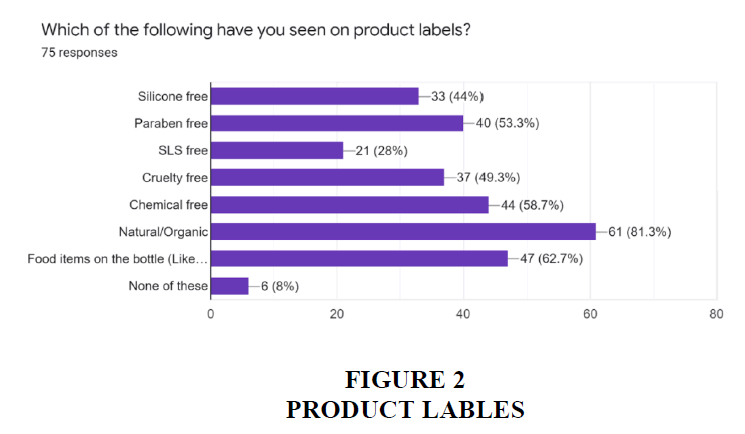

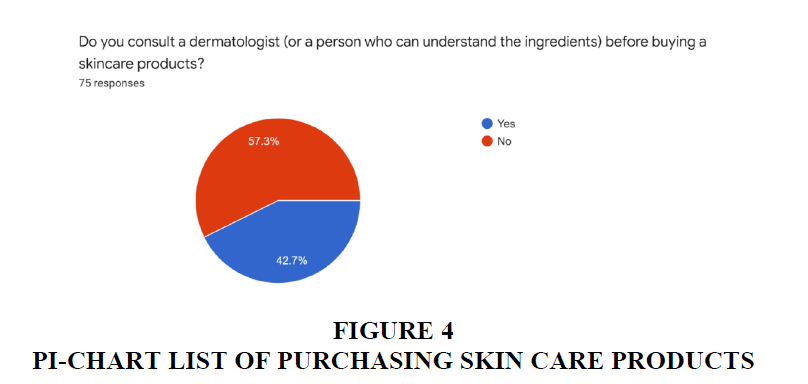

The result of the survey is concise and easy to understand. Clearly, a lot of brands greenwash their consumers with labels such as “silicone free, sulphate free, paraben and preservatives free”, however, they fail to see the impact it has on the Indian consumer market. Indian consumers like to be associated with “natural” and “environmental-friendly” titles given the history of India in Ayurveda, (Malik et al., 2022) however, these brands create fear regarding safe products, and showcase few ingredients as potent and injurious.

Brands prefer to market and advertise their products by sending their products to social media influencers who already have the skin goals the brands claim. Due to this, consumers do not cater to their skin needs and believe that what works for somebody else would work for them too.

Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

Sulfates, mainly Sodium Lauryl Sulfate, also popularly known as SLS, have become notorious since various unscientific and unverified articles and sites declared SLS as a scalp irritant and accused it form a cataract, i.e., injurious to the tissue of the eye’s lens. The rumour began after a study published by Green where a chemically damaged cornea of an animal was exposed to a high concentration of SLS, i.e., 20% SLS for 14 days in a laboratory. The outcome of the experiment was a “slowed healing process” (Green et al., 1989). However, the outcome was wrongly quoted as “SLS containing products lead to blindness or severe corneal damage.”

In practice, Sulfates are affordable ingredients in cosmetic and cleaning products which increase lather formation (Freitas et al., 2020). SLS is a water-soluble, non-volatile and biodegradable compound that can be derived from synthetic and environmental resources, such as coconut oil, petrolatum, and so on. Sulfates are used to remove dirt and excess sebum produced from hair and scalp, which makes hair dry. Additionally, SLS is used in skincare and hair care products to decrease the greasy effect and is also the main ingredient for makeup removal (Cline et al., 2018)

Preservatives

Preservatives are chemicals that prevent the rotting of food and cosmetics, which, in the past, have caused various “contact allergy epidemics”, such as the widespread of formaldehyde. Formaldehyde is an odourless and colourless gas used in nail paints, clothing and hygiene products which have decreased over time due to negative public opinion. Eventually, Formaldehyde-releasing preservatives (FRPs) were developed and used since the percentage used isn’t sufficient to cause a skin reaction. FRPs eventually were used as a replacement in personal care, cosmetic and cleaning products (Dubey & Das, 2021).

Parabens are affordable, odourless and colourless preservatives used in food and cosmetics. Individuals who cannot tolerate parabens can mostly tolerate paraben-containing products. This phenomenon is termed the “paraben paradox” (Milam & Cohen, 2019). Parabens can act like estrogen in bodies and thus the media and press labelled paraben as “endocrine disruptors” claiming that it could lead to breast cancer. However, studies and research has failed to validate the claims.

Products are now being branded as “paraben free” and are sold to customers to pacify them. The brands are not adding parabens to their ingredients list anymore and branding their products as “natural”.

Silicone

Silicones are synthetic, and even though their derivation in various cases may be through natural resources, the process of creating silicone leads to the production of microplastics. In recent studies, when the skin barrier is compromised, or if the skin is irritated, silicone-based ingredients like methicone and dimethicone are used to calm the skin and recover the skin barrier (Lichterfeld-Kottner et al., 2020). Dimethicone forms an artificial barrier above the skin, improves water retention and limits exposure to free radicals. (Sounouvou et al., 2021). Dimethicone is used in products to give a silky, smooth texture and it spreads easily, thus is enjoyed by a vast percentage of consumers. It is used in skincare and cosmetic products to gain a matte finish. It is observed that dimethicone is good for people with eczema since it reduces inflammation, PIE (Post Inflammatory Erythema), itching, dryness and roughness within fourteen days of consistent use (Arora et al., 2022).

However, various reports describe that due to the extreme stability of silicones, they do not biodegrade, and when released into the environment, they remain there for years, causing harm to the aquatic environment (Bom et al., 2019).

But brands shun silicon in their products by claiming that it causes acne and leads to rough patches on the skin.

Discussion

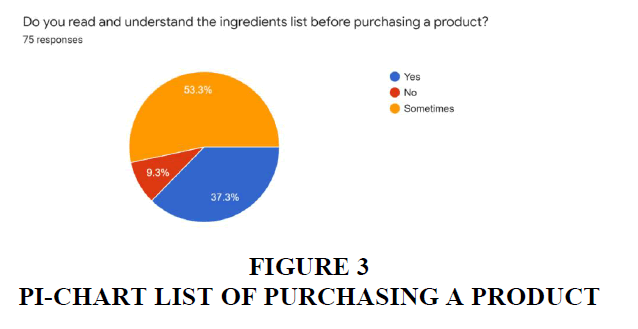

Various authors cited in this paper talk about the phenomenon of false marketing, greenwashing and influencer marketing. In previous literature, authors have shown concern regarding demonizing safe ingredients such as sulphates and various chemicals. This paper takes the study a step further and talks about the origination of fear-mongering around certain safe ingredients and how they impact consumer buying behaviour in the Indian market. Overall, the studies can easily conclude that consumers want to know what they use and thus they believe in the claims of the brands instead of researching and knowing about the ingredients before completely avoiding them.

Conclusion

Fear mongering is a common phenomenon seen in the business industry where brands create fear against certain things which leads to incorrect consumer knowledge and fear against using that thing. In the beauty industry, fear-mongering has existed for a long time and brands build profits on it. Sulphates are a must in cleansers and shampoos since they lead to lather creation and they are the main ingredient used for removing dirt and pollution. Parabens are the safest form of preservatives, and preservatives are essential in skin care because they help in avoiding the build-up of fungus and are responsible for maintaining the long shelf life of products. Silicones are silky ingredients that increase hydration in the skin and help in the wound healing process of the skin, however, they are bad for the environment. When brands spread fear against skin-safe ingredients, then dermatologists and cosmetologists with a large audience should debunk these myths and make people aware of these ingredients.

References

Arora, P., Shiveena, B., Garg, M., Kumari, S., & Goyal, A. (2022). Curative Potency of Medicinal Plants in Management of Eczema: A Conservative Approach. Phytomedicine Plus, 100256.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arouri, M., El Ghoul, S., & Gomes, M. (2021). Greenwashing and product market competition. Finance Research Letters, 42, 101927.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bom, S., Jorge, J., Ribeiro, H.M., & Marto, J. (2019). A step forward on sustainability in the cosmetics industry: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 225, 270-290.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cline, A., Uwakwe, L.N., & McMichael, A.J. (2018). No sulfates, no parabens, and the “no-poo” method: a new patient perspective on common shampoo ingredients. Cutis, 101(1), 22-6.

Dubey, S.K., & Das, P. (2021). Formaldehyde: Risk assessment, environmental, and health hazard. In Hazardous Gases (pp. 169-182). Academic Press.

Freitas, R., Silvestro, S., Coppola, F., Costa, S., Meucci, V., Battaglia, F., ... & Faggio, C. (2020). Toxic impacts induced by Sodium lauryl sulfate in Mytilus galloprovincialis. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 242, 110656.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Green, K., Johnson, R.E., Chapman, J.M., Nelson, E., & Cheeks, L. (1989). Preservative effects on the healing rate of rabbit corneal epithelium. Lens and eye Toxicity Research, 6(1-2), 37-41.

Gupta, A., & Kala, P. (2021). Impact of covid-19 pandemic on purchase and usage patterns of cosmetics among women of gurugram (india). International Journal of Management (IJM), 12(6), 250-259.

Lichterfeld-Kottner, A., El Genedy, M., Lahmann, N., Blume-Peytavi, U., Büscher, A., & Kottner, J. (2020). Maintaining skin integrity in the aged: a systematic review. International journal of nursing studies, 103, 103509.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Malik, A., Pereira, V., Budhwar, P., Varma, A., & Del Giudice, M. (2022). Sustainable innovations in an indigenous Indian Ayurvedic MNE. Journal of Business Research, 145, 402-413.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Milam, E.C., & Cohen, D.E. (2019). Contact dermatitis: emerging trends. Dermatologic Clinics, 37(1), 21-28.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pal, A., Panda, P., & Mukkamala, S. (2020). Recent Trends of Cosmetics in India: A Review on Marketing Strategies and Consumer Behaviour. International Journal of Management (IJM), 11(7).

Scieszko, E., Budny, E., Rotsztejn, H., & Erkiert?Polguj, A. (2021). How has the pandemic lockdown changed our daily facial skincare habits?. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 20(12), 3722-3726.

Sounouvou, H. T., Defourny, C., Gbaguidi, F., Ziemons, E., Piel, G., Quetin-Leclercq, J., & Evrard, B. (2021). Development of a highly persistent silicone-based sprayable emulsion containing essential oils for treatment of skin infections. International journal of pharmaceutics, 596, 120214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Talwar, S., Dhir, A., Singh, D., Virk, G. S., & Salo, J. (2020). Sharing of fake news on social media: Application of the honeycomb framework and the third-person effect hypothesis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102197.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

van der Schyff, V., Suchánková, L., Kademoglou, K., Melymuk, L., & Klánová, J. (2022). Parabens and antimicrobial compounds in conventional and “green” personal care products. Chemosphere, 297, 134019.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 14-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12330; Editor assigned: 18-Jul-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-12330(PQ); Reviewed: 01-Aug-2022, QC No. AMSJ-22-12330; Revised: 26-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12330(R); Published: 05-Sep-2022