Review Article: 2020 Vol: 19 Issue: 1

Gateway Theory of Internationalization: The Case Of OBOR/BRI in Zambia

Natasha Mwila, De Montfort University

Abstract

There has been growing interest in the continued increase of Chinese foreign direct investment across the globe. At worst, Chinese investment in Africa has been viewed with suspicion and likened to an era of neo-colonization. China’s foreign direct investment has been amplified by the “one-belt-one-road” or “belt and road initiative”. This has opened an academic debate on what internationalization practices are at play in the context of Chinese foreign direct investment under the “one-belt-one-road” or “belt and road” initiative. This paper seeks to contribute to the academic discussion by investigating whether there is merit to the neo-colonial argument based on the case of current Chinese internationalization practices in Zambia, a country included in ‘one-belt-one-road’ or “belt and road” initiative. The investigation finds that there is merit for a contrasting theory, a gateway theory of internationalization, which casts a different perspective on the intentions of China in “one-belt-one-road” or “belt and road” countries.

Keywords

OBOR, BRI, Internationalization, China, Zambia.

Introduction

Background to OBOR in Africa

“One Belt One Road” (OBOR), also known as “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) is popularly regarded as a Chinese infrastructure project. What comes to many a mind is the Chinese construction of roads, bridges, railways and ports to increase China’s geographical connectivity to the rest of the world. As the initiative has unfolded, it has proved to be more than that. As presented in several action plans, OBOR is also about education, maritime, culture, environment, sports and tourism. This brings into question what the “real” agenda is for China with this initiative. Critics have touted it as a pathway to overtaking “the west” as the world’s superpower (Ohashi, 2018) whereas China has declared more reserved intentions than that to only increase global trade and economic development (Dunford & Liu, 2019). China has in recent times become one of the main trading partners of African countries. This significant role of China in African economies is presented in Table 1 which summarizes the African countries (26 out of 54, very well nearly half) that have China as their biggest importer, exporter or overall trade partner.

| Table 1 Major Trade Partnerships of African Countries with China | ||

| Country | China Imports | China Exports |

| Algeria* | X | |

| Angola* | X | X |

| Burkina Faso | X | |

| Cameroon* | X | |

| Chad* | X | |

| Congo, Democratic Republic | X | |

| Congo, Republic* | X | |

| Egypt* | X | |

| Equatorial Guinea* | X | |

| Ethiopia* | X | |

| Ghana* | X | |

| Guinea* | X | |

| Kenya* | X | |

| Madagascar* | X | |

| Mauritania* | X | |

| Mauritius | X | |

| Nigeria* | X | |

| Rwanda* | X | |

| Sierra Leone* | X | |

| Somalia* | X | |

| South Africa* | X | X |

| South Sudan* | X | |

| Sudan (North)* | X | X |

| Tanzania* | X | |

| Togo* | X | |

| Uganda* | X | |

Africa cannot be overlooked if OBOR is to be a success as it has, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in China, “indispensable and important historical and geographic links to China” (Africa Times, 2019). Although not the principle matter of this study, this fact is worthwhile considering in determining China’s motives for OBOR in Africa and theoretically mapping out its internationalization strategy. On the official website of the Belt and Road initiative, China lists 40 African countries, including those in Table 1 with asterisks as well as Burundi, Côte d'Ivoire, Cape Verde, Djibouti, Gambia, Gabon, Liberia, Libya, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Senegal, Seychelles, Tunisia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. These countries all have a part to play in the belt and road and in providing access to key resources and linkages necessary for the initiative.

Agriculture in One Belt One Road

Although not a prominent feature of OBOR publications, there have been suggestions that OBOR may also be a project geared towards improving China’s food security position (Arsecati, 2018). This study commenced with this view in trying to understand what if any interest there may be in agriculture in relation to OBOR. This interest was informed by the fact that aside from copper mining, Zambia remains a largely agrarian economy. The food security argument has been challenged because in China, like in many countries across the globe, food security is largely the responsibility of the country’s small-scale farmers. As part of OBOR, large commercial agribusinesses are supported in their operations by the government of China in a range of areas including farm production outside China and encouraging more imports (Belt and Road News, 2019). This contrasts with the view that the primary support is for small scale farmers. Furthermore, evidence points to the fact that China exports more food to Africa than it imports (Brautigam, 2009). This then presents an alternative hypothesis for China’s engagement on the African continent in the agricultural sector - it may simply be business and a potential gateway to other industries.

With food in Africa being a highly politicized topic perhaps the silence around China’s relationships in this area on the continent is deliberate. In 2017, the Ministry of Agriculture in China released its “Vision and Action on Jointly Promoting Agricultural Cooperation on the Belt and Road”. It posits that agriculture is a vehicle for cooperation and building common interests for countries in OBOR (Ministry of Agriculture, 2017). This paper supports the position that cooperation may be enhanced through agriculture but contends that there is limited benefit for OBOR countries in the way agricultural initiatives have been implemented in Africa, especially bearing in mind that it may simply business and a gateway for China.

This paper examines one of four positions presented in the “Vision and Action on Jointly Promoting Agricultural Cooperation on the Belt and Road”. The prominent issue of contention has been the question of ‘mutual benefit’. Examining this position will establish whether there is merit to the proposed hypothesis of this study being that China’s interest in African agriculture is simply as a business gateway. The positions of the “Vision and Action on Jointly Promoting Agricultural Cooperation on the Belt and Road” are:

1. Favorable conditions are laid for countries to achieve complementarities in agriculture and share development opportunities.

2. China is ready to contribute its wisdom to the global governance on food and agriculture and share experience with Belt and Road countries so as to contribute more to agricultural and economic growth in the world.

3. Concerted efforts are solicited to realize agricultural modernization with high efficiency, product safety, resource conservation and environmental consciousness.

4. Mutual benefit. Interests and concerns of all parties will be accommodated, advantages in agriculture of all countries be synergized, and cooperative potentials tapped.

OBOR has enabled agricultural market access for China through the privileges of OBOR countries such as Senegal -whose partnership allows China access to the United States (US) and European Union (EU) markets. Senegal has quota and duty-free privileges in the US and everything but arms trade arrangement with the EU which China benefits from (Belt and Road News, 2019). This relationship supports the proposed gateway theory as China has been able to extend its activity from agriculture to manufacturing and exporting goods from the special economic zone it has established in Dakar.

The Case of China in Zambian Agriculture

China has a long-established relationship with Zambia dating from its historical involvement in the construction of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway (TAZARA) in 1976. China has also increased its foreign direct investment in Zambia’s energy and copper mining sectors (Lubinda & Jian, 2018). China has brought to Zambia financial and technical assistance in many of these projects. China has had a continuous interest in these projects, presently reviving TAZARA as part of the OBOR initiative. Although most reports of China in Zambia tend to focus on the rail, energy, mining and construction sectors, a notable area of growth is China’s interest in agriculture which this study seeks to explore further.

China National Agricultural Development Group Corporation was the earliest Chinese investment in Zambian agriculture in 1990 through the ownership and operation of Jonken farm (Lubinda & Jian, 2018). Farm ownership has evolved from exclusively state ownership to include private Chinese farmers. The areas of activity include wheat, maize, soya beans, eggs, chickens, animal produce, cabbage and cattle.

According to Chatelard (2014), the pattern of Chinese interest in Zambian agriculture has evolved. Prior to the 1990s, the focus of Chinese activity in Zambian agriculture was the facilitation of agriculture at a subsistence level and building up local capacity through voluntary Chinese experts who would be subjected to a strict code of conduct and expected to return to China upon completion of their services; whereas by 1990, more commercial arrangements were commonplace and Chinese interest could be seen in Zambian commercial farms (Chatelard, 2014).

In 2009, China Nonferrous Mining Company (CNMC) launched a food and tobacco processing special economic zone in Lusaka, the country’s capital city. It has been consistently reported that there are 2 state owned and 30 private Chinese firms invested in the Zambian agricultural sector. Although historical entrants from China into Zambia’s agriculture were large scale, reports by Chatelard & Chu (2015) suggest that in more recent times this profile has changed. Many of the Chinese farmers in Zambia produce at a small scale with no indication that they are supported by the Chinese government. Their research (Chatelard & Chu, 2015) found that most of the Chinese farmers in Zambia have no prior background in farming and in fact learn to farm whilst in Zambia. This implies that there is less potential for technological transfer to local Zambian farmers in comparison to the potential from their larger scale counterparts. There is further concern about what practices are being transferred from China to Zambia when it has exacerbated environmental degradation in its own country because of overusing chemicals which in turn has displaced many farmers out of the market (Arsecati, 2018). These issues presented undermine the four positions claimed in the “Vision and Action on Jointly Promoting Agricultural Cooperation on the Belt and Road” and on the face of it, support the gateway theory hypothesis.

It is suggested that one of the gateways sought through Zambia’s agriculture is access to transport networks and land resources. Zambia’s agriculture presents a gateway opportunity. According to Alden (2013), “China’s role in African agriculture has expanded to include a growing trade relationship which itself has been tied to provisions for project financing of agricultural infrastructure”. The need to develop agriculture related transport infrastructure is directly correlated to accessing and creating transport networks. Furthermore, there have been indications that China seeks to use agricultural programs in Africa to resettle its displaced farmers (Li, 2007). Agriculture gives access to land and this in turn is correlated to access to land outside China for China’s population. This desire for land access is evident in the desire for long term leases of agricultural land in Zambia (Hairong & Sautman, 2010).

It is worth noting however that there are numerous Chinese private efforts in Zambian agriculture that are a result of individual entrepreneurial interests and that are not necessarily driven or supported by the Chinese government (Alden, 2013). The private Chinese farmers have not, to date, been involved in exporting but have been active in supplying produce to the local Zambian market. The gateway is different for this cohort of farmers given that Zambia, and perhaps the broader context of Africa, offers the prospect of new markets with reduced levels of competition from their fellow Chinese counterparts.

Theories of Internationalization in the Case of China in Zambian Agriculture

Alden (2013) observed that “the approach of China in African agriculture has been an eclectic one, rooted in technical cooperation aimed at achieving development goals but branching out into commercially motivated projects and market-based trading arrangements”. This theoretical analysis builds on this observation.

The gateway hypothesis of this paper is further built on the work of Brautigam (2009) and Foad (2011) who identified the drivers of Chinese investment in Zambia as follows:

1. The need to find new export markets to fuel further expansion of domestic production, and now, with the rising labor costs in China, there is need to secure opportunities for Chinese enterprises under the going global strategy as the Chinese economy transitions into the ‘new normal’ phase of development.

2. The need for allies among developing countries to counterbalance the predominance of the developed countries in international organizations like the UN and IMF.

Dudhia (2012) surmises that the model of Chinese investment in Zambia has progressed during different periods of time and this has been conceptualized for this paper as follows:

• Pre 1990- Investment carried out largely by either state-owned enterprises or joint ventures.

• From 1990 onwards-Wholly owned enterprises established through mergers and acquisitions replace joint ventures, some state backed.

• From 2000 onwards-Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) adopts aid provision especially in infrastructure development.

From the outset, this work dismisses neocolonialism as a theoretical explanation for China’s involvement in Zambian Agriculture. This is in support of earlier analyses by other scholars including Chen, Dollar & Tang (2015) as well as Junbo & Frasheri (2014). Neocolonialism has been rarely defined in scholarly works reviewed for this study. However, this study argues that it ought to have demonstrable features as laid out by Loomba (2005). These features are all the features of colonialism but for the direct political rule of one nation over another. There is an absence of a formal colony but direct control over economic, social and labor relations. China may have influences in these areas in Zambia, but such influence has been generated on the basis of mutual agreement between the countries rather than force.

Outward FDI from China

China has a China Africa Policy in which Chinese enterprises that are willing to invest in Zambia have been encouraged and pledged support to. In this policy China explicitly expresses its desire to negotiate Free Trade Agreements with African Countries to gain access to the Zambian and other markets. Linked to this policy, China has been encouraging investment activity in Zambia through its "Going Out" strategy. Under this strategy, financial support can be rendered to Chinese companies from a host of state backed institutions including the Export-Import (EXIM) Bank of China, the China Development Bank, and more directly, the Ministry of Commerce.

FDI has overall positive effects but not for all sectors as noted by Hirschman who argued that the positive effects are limited in agriculture. The nature of the effects is largely determined by whether the primary purpose of FDI is to seek resources or to seek markets. The pattern of Chinese investments in Zambia has been in the initial stages to seek resources, then seek markets and finally when the businesses are fully functional and operational, use the country’s central landlocked position to gain access to its neighboring countries.

Although China is clearly engaging in outward FDI in Zambia, it appears that the rationale for this is market creation rather than market seeking or resource seeking. This is to further refute the neo-colonialist position of seeking markets or otherwise and, seeking resources.

Phoenix Nests: Chinese Special Economic Zones

Part of China’s global strategy is the establishment of special economic zones in selected countries. Zambia is one of these selected countries and to this end the China Cooperation Council submitted its plan for cooperation with the country in the areas of agriculture, construction of infrastructure, tourism, energy and the training and development of human resources. Following Zambia’s acceptance of the plan, Zambia hosts 2 of China’s Special Economic Zones.

The first is the Lusaka East Multi Facility Economic Zone which is also called the Zambia-China Economic & Trade Cooperation Zone (ZCCZ). Notably ZCCZ was the first Chinese overseas economic & trade cooperation zone established in Africa in 2006 (Zeng, 2016). The target sectors for the zone includes agriculture.

The second is the Chambishi Multi Facility Economic Zone (CMFEZ) established in 2007. Its priority sectors also include agriculture. Additionally, this zone taps into mining and construction.

Lin Yifu (as cited by Pairault, 2019) theorizes that these zones exist to minimize host government direct economic involvement and optimize the creation of a free and well-functioning market for a sector under gradual transformation. Using one sector to access another is the gateway hypothesis of this paper.

Pairault (2019) argues that the primary (more extremely, only) beneficiary of these zones is China. These zones support the “going out” strategy by creating a conducive environment for the Chinese enterprises to go to. The zones are a gateway to the broader OBOR initiative and agriculture has been adopted as a key facilitation of their establishment.

Chinese Zones of Influence

In 2015, Maswana published work on the trade intensity index of China relative to African countries and found that Zambia was one of ten with “a high relative trade intensity index with respect to China, implying that they are now locked into a relationship of dependency on China”, (Maswana, 2015). Maswana went on to argue that China, in these ten countries, had created zones it could influence economically and perhaps beyond. Although this finding appears to support the neocolonialism theoretical argument, this study rather views it as a finding supporting the gateway theory presented herein. The creation of economic dependency is indeed a method of neocolonialism but without a history of previous influence (as in the case of historical colonialism) and clear mutual agreement on the areas and conditions of trade (no force as in the case of historical colonialism that waters down to neocolonialism), this study finds that there is insufficient support for this theoretical position. The Chinese Zones of Influence may be positioned as hubs for resource extraction or markets for Chinese exports, both in support of the gateway hypothesis.

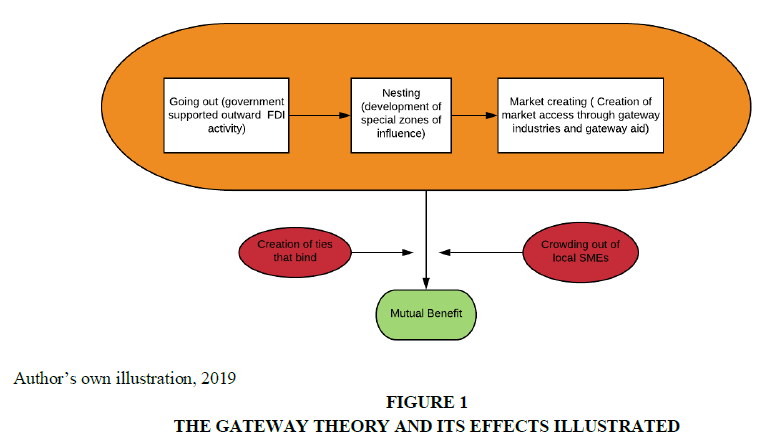

Figure 1 summarizes the proposition of this paper in that the Chinese OBOR initiatives follow the presented gateway model. This model consists of ‘going out’ which is Chinese government supported activities of outward FDI. ‘Going out’ is then followed by ‘nesting’ which is the development of special zones of influence in targeted OBOR countries. The influence may be generated through specific industries (like agriculture in Zambia) or through aid projects. Once the zones are established, desired markets can be created.

Current Effects of China in Zambia- the Position of Mutual Benefit Tested

Ties that Bind

Abdelghaffar et al. (2016) found that Zambia entered a pattern of business cycle synchronization due to a high dependence on Chinese FDI. This implies that there is an increased level of interconnectivity which may be of benefit to Zambia during prosperous times but on the flipside increases Zambia’s vulnerability during times of slowdown in China. Position 4 of mutual benefit is undermined by this effect.

Crowding Out of Local Small and Medium Enterprises

From the perspective of Zambian agriculture, there is a negative perception of Chinese firms because they are seen to be crowding out domestic SMEs. The public discontent warranted some government attention to the matter in 2015. The Zambian government response has been to introduce Reservation Schemes under the Citizens Economic Empowerment Act. These reservation schemes promote Zambian ownership in four sectors; block making, quarrying, poultry, and domestic haulage. To promote Zambian ownership, The Act prohibits fully foreign owned firms in these sectors but supports and encourages joint venture creation for foreign and domestic investors. The policy allows existing firms to continue their operations, except for the poultry sector which is perhaps the most controversial sector. In this sector, The Act (Citizens Economic Empowerment Commission, 2020) has permitted existing foreign owned enterprises to produce and sell live birds to wholesale buyers but are prohibited from selling live birds in markets.

Although the Zambian government has tried to encourage partnerships and joint ventures between foreign and domestic firms, their success remains difficult to establish. Based on data from the Zambia Development Agency, between 2007 and 2015, 330 investment certificates were issued to Chinese nationals and only 16 of these (less than 5%) were for joint ventures with Zambian partners (Mutale, 2015). It is unclear whether the low number of joint ventures is due to difficulties in procedure or reluctance from either foreign or Zambian nationals. In either case, position 4 of mutual benefit is undermined by this effect. After 2015, the reporting of investment data by the Zambian Development Agency changed to report on the value of certificates rather than the number of certificates issued. This has made it difficult to track the number and nature of investments between 2015 and 2020. As the primary source of data as a statutory body, it has influenced the reporting of these vital statistics by the Ministry of Trade, Commerce and Industry, Zambia Statistics Agency and the Bank of Zambia. Other international sources of this data like the International Trade Center and World Bank also only report up to 2015 for Zambia. Between 2016 and 2019, US$ 707 million of Joint Venture investment was reported (Zambia Development Agency, 2019).

The joint venture argument is that they increase the prospects of mutual benefit much more than cases of full foreign ownership. This argument is stated in a World Bank report of empirical studies on foreign ownership which found more positive spillover effects of joint ventures than fully foreign-owned firms (Farole & Winkler, 2014).

Conclusion

Chinese companies adapt their business models according to the context (Calabrese & Weng, 2018). Consequently, there are different outcomes of Chinese investments in different countries depending on the Chinese state-owned companies involved, their Chinese province of origin and outcomes of negotiations with the said countries (Scoones, 2019).

To reiterate, the four positions of the vision in agriculture for OBOR are as follows:

1. Favorable conditions are laid for countries to achieve complementarities in agriculture and share development opportunities.

2. China is ready to contribute its wisdom to the global governance on food and agriculture and share experience with Belt and Road countries so as to contribute more to agricultural and economic growth in the world.

3. Concerted efforts are solicited to realize agricultural modernization with high efficiency, product safety, resource conservation and environmental consciousness.

4. Mutual benefit. Interests and concerns of all parties will be accommodated, advantages in agriculture of all countries be synergized, and cooperative potentials tapped.

The first three positions are largely supported by the model presented in this study at various points of the model as follows:

1. “Favorable conditions are laid for countries to achieve complementarities in agriculture and share development opportunities”: This is a necessity for nesting and the development of special zones of influence.

2. “China is ready to contribute its wisdom to the global governance on food and agriculture, and share experience with Belt and Road countries so as to contribute more to agricultural and economic growth in the world”: This is compatible with both encouraging ‘going out’ and enabling ‘nesting’.

3. “Concerted efforts are solicited to realize agricultural modernization with high efficiency, product safety, resource conservation and environmental consciousness”: This too is a necessity for nesting and the development of special zones of influence.

China’s position is that its ‘going out’ policy is intended for mutual benefit of China and OBOR countries. However, this study has shown that the extent of mutual benefit is greatly diminished by the moderating effects of the creation of bonded business cycles and the effect of crowding out of local SMEs in gateway and target industries. There is a scope for further investigation into the measures of these effects.

References

- Abdelghaffar, N., Bryant, K., Bu, C.S., Campbell, M., Lewis, B., Low, R., Namit, K., Paredes, D., Silva, A., & Yu, C. (2016). Leveraging Chinese FDI for diversified growth in Zambia. In the Woodrow Wilson School Graduate Policy Workshop.

- Africa Times. (2019). China notes Africa’s key BRI role ahead of forum in Beijing.

- Alden, C. (2013). China and the long march into African agriculture. Cah Agric, 22(1), 16-21.

- Arsecati, S. (2018). Is the Belt and Road a Food Security Plan? Belt & Road Advisory.

- Belt & Road News. (2019). The Belt and Road Initiative: Chinese Agribusiness going Global.

- Brautigam, D. (2009). The dragon's gift: the real story of China in Africa. Oxford University Press.

- Calabrese, L., & Weng, X. (2018). Chinese investment and small-scale commodity producers in Africa. Growth Research Programme.

- Chatelard, S.G. (2014). Chinese agricultural investments in Zambia. Great Insights, 3(4).

- Chatelard, S.G., & Chu, J.M. (2015). Chinese agricultural engagements in Zambia: A grassroots analysis. SAIS China Africa Research Initiative.

- Chen, W., Dollar, D., & Tang, H. (2015). China’s direct investment in Africa: Reality versus myth.

- Citizens Economic Empowerment Commission. (2020). Reservation Schemes.

- Dudhia, A., & Dudhia, M. (2012). Silk Road or Dragon Path? The Impact of Chinese Investment in Zambia.

- Dunford, M., & Liu, W. (2019). Chinese perspectives on the Belt and Road Initiative. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12(1), 145-167.

- Farole, T., & Winkler, D. (2014). Making foreign direct investment work for Sub-Saharan Africa: Local spillovers and competitiveness in global value chains. The World Bank.

- Foad, H.S. (2011). China's Trade with Africa and the Middle East: A Tale of Markets, Politics, and Resources. Politics, and Resources.

- Hairong, Y., & Sautman, B. (2010). Chinese farms in Zambia: from socialist to “agro-imperialist” engagement? African and Asian Studies, 9(3): 307-333.

- Junbo, J., & Frasheri, D. (2014). Neo-colonialism or De-colonialism? China’s economic engagement in Africa and the implications for world order. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 8(7): 185-201.

- Li, C. (2007). South China Morning Post.

- Loomba, A. (2005). Colonialism/postcolonialism. 2nd edn. Routledge. London.

- Lubinda, M.C., & Jian, C. (2018). China-Zambia Economic Relations: Current Developments, Challenges and Future Prospects for Regional Integrations. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 6(1): 205-223.

- Maswana, J.C. (2015). Colonial patterns in the growing Africa and China interaction: dependency and trade intensity perspectives. Journal of Pan African Studies, 8(7): 95-112.

- Ministry of Agriculture, P. R. China. (2017). Vision and Action on Jointly Promoting Agricultural Cooperation on the Belt and Road.

- Mutale, C. (2015). Chinese investments in Africa’s SME sector: A case study of Zambia.

- Ohashi, H. (2018). The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the context of China’s opening-up policy. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 7(2): 85-103.

- Pairault, T. (2019). China in Africa: Phoenix nests versus Special Economic Zones.

- Scoones, I. (2019). The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative: What’s in it for Africa?

- Zeng, D.Z. (2016). Multi-Facility Economic Zones in Zambia: Progress, Challenges and Possible Interventions. Centre of Structural Economics Peking University.