Research Article: 2017 Vol: 9 Issue: 1

Foreign Direct Investment Attractiveness Policy Empirical Study Applied To Tunisian Territory

Awatef Gdairia, University of Tunis El Manar

Fethi Sellaouti, University of Tunis El Manar

Keywords

FDI Attraction, Dunning's Eclectic Paradigm, PLS Modelling.

Introduction

Today, territorial attractiveness has become an important component of economic policies and seducing potential investors is now a major objective for all states, seen the positive impact of FDI inflows on the host countries (Krugman & Obstefld, 1999). In addition, studying of territorial attractiveness as a concept entails two approaches that can be taken into consideration: A theoretical approach based on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) determinants and a strategic one based on territory promotion policies.

First, the Dunning’s eclectic theory provides an important theoretical framework in explaining how competitive advantages of the firm are in concordance with the comparative advantages of the host country. The Dunning’s paradigm, often called by the OLI paradigm, explains that multinational firms decide to undertake FDI abroad in the presence of variables related to the Ownership specific advantages, Location-specific advantages and internalization advantages. A rich empirical literature on OLI factors were examined as determinants of FDI (Buckley et al., 2018; Anarfo, Agoba & Abebreseh, 2017; Myna, 2017; Gorynia et al., 2016; Makoni, 2015. They included several aspects of variables: economic, political and cultural which influence on FDI decision.

Secondly Good attractiveness may be built by a state deciding to launch FDI promotion policies (Giuseppina, 2016; Lv & Spigarelli, 2016; Dadzie et al., 2016) to create a good territory image Wells et Wint (1990) to provide services aiming at reducing potential investors’ transaction costs and providing financial incentives to invest in the country (Andreff, 2013).

The attraction of FDI is a major concern for most developing countries, including Tunisia. Then, successive governments have started territorial promotion policies for several years (in 1995 l’agence de promotion de l’investissement extérieur or Foreign Investment Promotion Agency FIPA-Tunisia was created in addition to the Code on Foreign Investment Incentives and fiscal policies in order to attract FDI that can be potential development sources and can form a good competitiveness challenge). Despite the deployed efforts, the results are insufficient and national competitiveness is falling in comparison with competitors. In this respect, it is worth studying the tools used by governments to motivate foreign investors on the one hand and to examine the impacts of these policies on FDI flows on the other. The present article fits within this context and aims to study territorial attractiveness in the Tunisian context. The determinants of attractiveness are analysed empirically based on the eclectic theory of dunning. A conceptual model corresponding to the interaction of the OLI variables and the strategies followed by Tunisia will be empirically tested.

The present paper will be divided as follows: introduction, theoretical literature review and conceptual model, followed by methodology and data sources, presentation of the econometric modelling and the results. The latter are linked to territorial attractiveness factors as well as issues related to the efficiency of the host country’s policies.

Theoretical Axes And Conceptual Model

Literature Review

The Dunning’s eclectic paradigm (1998, 2001b, 1995, 2004) has become a good starting point for analysing the most important determinants on FDI decision. It considers that foreign firms decide to undertake FDI in the presence of three advantages. Ownership-specific advantages (that can be linked to specialized knowledge, innovations, technological development, economies of size and competition); location-specific advantages (concerning the economic, political and cultural variable’s specific to the host countries); and internalization advantages (which are concerned with reducing the costs of transactions) (Cantwell & Narula, 2001; Dunning, 2004). It suggests that variables related to OLI factors are related to each other: The ownership-specific advantages depend on the advantages that the host country brings to them and the mode of penetration chosen to gain market share. The specific advantages of a country are influenced, first, by the specific benefits that firms bring, such as in research and development and secondly, by the ways in which they penetrate, as if they are establishing a seat in the country. The choice of the internalization process depends on the advantages that a country provides and also on the specific advantage that the firm wants to relocate to a new host country.

Ownership-Specific Advantages

Empirical literature offers evidence on the links between the company’s advantages and FDI input. Several studies such as those of Lien & Filatotchev (2014) and Strange & Buckley (2009) have highlighted the impact of company criteria (such as size) on FDI. Other empirical studies examined the company’s advantages under the intensity of R/D (used as an alternative measure to technology and knowledge) showing its impact on FDI.

Cui, Meyer & Hu (2013) cite the works of Kim, Kim & Kim (2012) and that of Ray who found a positive correlation between the level of Research and Development (R/D) in the industrial sector and in FDI. The works of Chen, Chang & Zhang (1995), Tan & Vertinsky (1995) conclude the existence of a positive relation between R/D intensity and international expansion. Tan & Vertinsky (1995) grouped the empirical studies on intellectual property and FDI showing that several surveys confirm the positive relation between R/D and companies' inclination to do business abroad. This relationship was specifically confirmed in the case of Japanese companies by Chen, Chang & Zhang, (1995) in the period of 1980.

In other studies, people’s know-how is measured by their capacity for international management of the company which can be acquired through international experiences in foreign markets. The latter are able to reduce FDI-related uncertainties as well as transaction costs (Tallman, 1991). In addition, the organization’s efficiency is used as managerial know-how and is used by Prahalad & Doz (1987); Siripaisalpipat & Hoshino (2000); As a proxy to evaluate the way in which the firm’s specific advantages affect the subsidiary’s performance. Tan & Vertinsky (1995) assert that the size of the company was identified by theoretical as well as empirical studies on FDI as the most important source bringing forth a strategic advantage. Starting from the conclusions of Tallman (1991) and Tan & Vertinsky (1995), who consider that encouraging companies to invest abroad can be influenced by their position in the domestic market.

Besides, in other studies, the mother company’s size reflects its capacity to absorb high marketing costs through patents and contracts and through realization of scale economies on foreign markets (Ogasavara & Hoshino 2007). Other studies such as those of have concluded that the size of the company has a positive impact on FDI.

In addition, the search for strategic assets has become an important strategic incentive that motivates FDI (Cui, Meyer & Hu, 2013). As such, the recent works of Rui & Yip (2008) and Cui, Meyer & Hu (2013) suggest that due to their lack of specific advantages and weak local assets available, National Implementing Measures (or MNE in French) usually resort to FDI to acquire strategic assets. Based on the above arguments, we hypothesize that Ownership-specific advantages influence FDI decision.

Location-Specific Advantage (L)

There is relatively extended empirical literature on the characteristics of destinations that seem to attract foreign investors. Although it may be possible those investors are attracted by regions characterized by favourable infrastructure and governance, most of the empirical literature highlighted the economic determinants. There is abundant literature review on the link between the location’s advantages and the decision to invest abroad. In addition, research on this question (FDI determinants) was corroborated by statistical analyses, as such, economic, political and institutional factors seem to have a causal link with FDI flows.

Asiedu (2002) collected subsequent studies that have used the variable (market size, cost of labour, political instability, infrastructure quality, launching and taxes). On the one hand, this author shows that these factors cannot have the same effect depending on the country. On the other hand, the results concluded by this study show that a good infrastructure has a positive and significant impact on FDI in developed countries; yet this factor is not significant in Sub-Saharan Africa.

More recently, Alaya, Nicet-Chenaf & Rougier (2007), by referring to the works of collected and classified the literature existing on location determinants as economic, political, institutional and motivational determinants.

Other studies examine the role of political and institutional factors with results that confirm the solidity of these factors as important determinants in FDI location. Stein & Daude (2001); Kinoshita & Campos (2004); Link the impacts of agglomeration to the variable Governance as FDI determinant.

Additionally, Ghemawat (2001) posits that cultural distance is attributed to the way people interact with one another, with companies and institutions, religion, language and cultural norms. These determinants can make the difference between two countries and can discourage commerce and investment between countries. As such cultural proximity will help reduce transaction costs and risks of foreign market penetration considering similarities of business laws, customs, the way business is done and eventually family links (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977).

Empirical justification of the role of human resources in FDI attraction was proved by Bouoiyour, Hanchani & Mouhoud (2009) who attribute FDI increase in some countries to the availability of human capital that becomes an attraction factor especially to multinational companies.

Ragozzino & Reuer (2011) studied the impact of geographical distance on the companies’ acquisition strategies taking into consideration the adverse selection risk and signals sent during the introduction to the stock exchange. However, the influence of the geographical distance as an important determinant in the decision to acquire abroad was also relativized, Métais, Véry & Hourquet (2010).

As it is the case with political, geographical and institutional factors, an abundant literature review was interested in the impact of economic factors on FDI attraction Blonigen, (2005). Based on the above arguments, we hypothesize that location-specific advantages influence FDI decision.

Internalization-Advantages

According to the internalization hypothesis, FDI springs from efforts deployed by companies in replacing transactions on the internal transactions market. This idea is an extension of the initial argument. In fact, the main motive behind internalization is the presence of externalities in production and factors markets.

The works of Morisset & Olivier (2002) fit within this scope. They show that corruption and bad governance increase administrative costs and consequently discourage the entry of FDI. Within this context, FDI’s establishment of foreign firms helps reduce transaction costs (Strange & Buckley (2009). Facilitates business exchanges increases market power, acquires competitive advantages and has access to competences and resources, Calipha, Tarba & Brock (2010). Based on the above arguments, we hypothesize that Internalization advantages influence FDI decision.

Strategic Approach

In addition, a good attractiveness can be created by a state deciding to have a FDI promotion policy. The construction of a good territory image, the provision of services to reduce potential investors’ transaction costs and financial incentives to invest in the country (Andreff, 2013). The main justification for the promotion of investments in FDI attraction aims at showing these positive results: there is evidence over long periods showing that countries that adopt FDI promotion policies have managed to attract foreign companies more than those who do not. Lim (2008) examines the investment promotion effort of the host government. The empirical results show that the efficiency of FDI promotion measured by (age of the IPA (Investment Promotion Agency), intensity of IPA staff abroad and the number of staff abroad (IPA)…positively affects FDI attraction. As such, financial incentives are wrongly considered by the host country as the most efficient instrument in encouraging a company to invest.

Morisset & Pernia (2000) have studied the impact of taxation policies in FDI composition, in order to know whether the taxation policy (fiscal incentives) concerns all FDI types or just FDI that have environmental protection policies or those that create jobs or those that allow the transfer of technology. Dunning et Narula (1998) propose the (cycle) model or that of the foreign direct investment development path. The gist is that FDI entering and exiting a country depends on its development level. On the other hand, Dunning (2000) suggests that according to the development level, the government can intervene in order to reduce some of the market weakness impeding development by committing to a variety of economic and social policies that will affect the market’s structure.

In order to benefit from spill overs, host countries are competing to attract foreign investors. This competition is explained by the contribution of these to production and therefore to growth. Theories of economic growth and development focus on increasing per capita real income and relate this increase to some important factors such as capital accumulation, population growth, technological progress and new discovery of natural resources. Also, FDI is considered a "substitute for trade" Fontagné & Pajot. The effect of FDI on the economy of the host country may have other impacts including, capital inflow, advanced technology transfer of know-how and new production and management methods, learning effect, direct job creation, training of staff, development of relationships with local suppliers and subcontractors, and indirect job creation.

The economic literature recognized that technology transfer is the main mechanism by which the presence of foreign firms can have positive externalities in the host country Blomström, Kokko & Globerman. On the other hand, FDI can have the effect of crowding out local investment. Some works such as those of Agosin & Mayer find such an effect, while other works, such as those by De Mello show, in a study of OECD member countries, the existence of a complementarity relationship between FDI and domestic investment. Chen, Yao & Malizard (2017), expose an extensive literature review on the relationship between FDI and domestic investment and, from an empirical study of the Chines economy, they conclude that there is a neutral relationship between FDI and domestic investment.

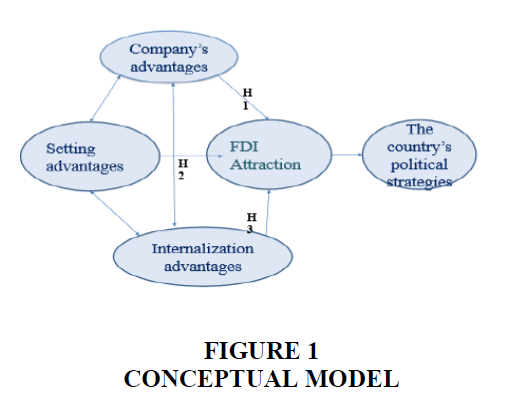

Taking into consideration the literature discussed above, the following conceptual model summarizes the OLI factors and FDI attraction policies.

Conceptual Model

Affected by its various approaches, we have opted for a conceptual model.

In this context, territorial attractiveness is created from a set of complex factors that are tightly inter-related. Within such a perspective, Dunning’s eclectic paradigm (1998) identifies the variables that are susceptible to influence FDI such as the ownership-specific advantages (O), the location-specific advantages (L) and the internalization advantages (I)(Figure 1).

Methodological Approach

From the literature review of our qualitative study, our conceptual model has three interactive sets of variables: variables linked to the location’s advantages and variables linked to the internalization advantages. Our research hypotheses spur from the set of defined relations in our research model numbering three main hypotheses.

H1: FDI in Tunisia are attracted by the Ownership-specific advantages.

H2: FDI in Tunisia are attracted by location advantages.

H3: FDI in Tunisia are attracted by internalization advantages.

Data

In order to ensure a better generalization of results and to examine the factors of attractiveness of the Tunisian territory, we have opted for a sample of 40 foreign companies established in Tunisia belonging to various sectors of activity. We have interviewed foreign investors installed in Tunisia over their degree of satisfaction with regards to OLI factors as well as the strategies followed by the host country. From Table 1 Appendix), we can see the specific items of each construct, as well as foreign investor’s satisfaction rate with respect to its items. The questionnaire survey is the collection method that we have selected. We have used the method of closed questions in which the surveyed individual (foreign investor) has to choose between several proposed answers following LIKERT scale that requires the interrogated person to express a certain degree of approval or disapproval following the proposed options.

Data Analysis Method

The retained data analysis method is that of structural equations modelling and the selected technique is the estimation by Partial Least Squares: PLS-SEM that we have treated with Smart PLS 2 software. We can attribute this choice to: the sample’s size, the presence of a nominal variable and a test of the partial model which attributes an exploratory aspect to the study. The evaluation of the measurement model corresponds to the verification of the unidimensionality of constructs as well as that of credibility criteria and measures’ validity. In order to verify the dimensionality of the measurement scale constructed in the questionnaire, we verify the credibility of the measurement scale of each construct separately. Cronbach alpha represents the most used index in measuring credibility. This coefficient helps verify the coherence in answers concerning a number of items serving to measure a construct. Then a principal component analysis (ACP) was carried out.

Principal component analysis (ACP) allowed us to conclude from the unidimensionality of the four constructs, except that of localization which seems to be bi-dimensional. This result was based while referring to the criterion of Kaiser according to which only the components having “initial eigenvalues” exceeding the unit (1), must be retained (Table 2 Appendix).

According to the indicators in (Table 3 Appendix), Rhô de Jöreskog indicators calculated for all constructs are superior to the threshold (0.5) recommended by Roussel et al. (2002). The three factors (O, L, I) have reached a Rhô de Jöreskog coefficient that is superior to (0.8).

Good credibility and internal coherence evaluated by Cronbach alpha’s test and Rhô de Joreskog prove that the homogeneity of the scales of three measurement constructs is sufficient and confirmed.

The convergent validity: evaluated using two measures: indicators’ individual credibility (the link between the latent variable and each of its indicators has to be significant) and internal coherence of the constructs. Credibility is evaluated by examining the Loadings (correlations) of indicators, in (Table 4 Appendix), with their respective constructs. All the indicators’ loadings used in this study were above the minimum that is required (0.5) (Hair et al., 2006). They suggest using an average variance extracted (AVE) in order to determine the convergent validity (Table 4 Appendix).

Discriminant validity indicates the extent to which each research model’s construct is at the same time unique and different from other constructs. We deem that discriminant validity is in conformity when the shared variance between a construct and another one in the model is inferior to the variance shared by the construct and its indicators.

As such, the square roots of the AVE and the correlations between the constructs inform us that the discriminant validity has been demonstrated concluding that the various constructs are theoretically and empirically distinct.

After purifications and the elimination of several ITEMS, we have obtained the results that are collected in (Table 1 Appendix) and that serve to verify the three criteria.

Estimation And Discussion Of Results

After validation of different measures that were purified using the PLS model, the estimation of the conceptual model comprises mainly 2 steps: evaluation of the internal model (structural), evaluation of the external model and validation of hypotheses.

The evaluation of the structural model helps verify its predictive quality. The analysis of the explained variance and the redundancy index generally give acceptable results.

The estimation of various relations represented in the model is done by examination of the path coefficients or standardized correlation coefficients or student’s-t values after bootstrapping.

Validation of the External Model

This step consists in estimating various relations represented in the model by examination of correlation coefficients and student’s-t after bootstrapping. As is shown by (Table 4 Appendix), the variable relative to company factors is a variable constructed from a set of qualitative variables such as capacity of international management, intensity of R&D, efficiency of organization and search for new capital.

Concerning the second constructed variable, it comprises the factors of location: (1) political stability, economic stability, quality of infrastructure and qualified work force, In addition to another location variable (2), constructed by factors reflecting the internal market’s functioning such as acquisition of existing assets, double taxation treaty, presence of co-company partners and specific investment projects. However, the fourth variable is constructed by internalization factors including corruption, imperfection of markets and power over the market, in other words, factors representing the modality of penetration of foreign firms in the host country’s market.

Finally, the constructed variable linked to FDI attraction factors groups factors linked to strategies and policies adopted by Tunisia to promote the Tunisian territory such as taxation, spending on R&D, market intervention and FDI support. The five constructed variables are significant at a threshold of 5%; this proves that for each variable the united factors constitute important attractions to measure.

Evaluation of the Internal Model and Verification of the Hypotheses Credibility

We here mean specification of the relations between latent variables (constructed) in which each relation is supported by a hypothesis based on a theoretical framework. The conceptual model was evaluated without an interaction effect between the OLI variables.

Table 5 Appendix groups the validity criteria of the model. It indicates the R2=0,437713 values respect the minimum (0.10) limit which indicates that (43.77)% of the use of the FDI attraction indicator can be explained by the constructs used in the model. The other criteria respect the suggested minimum.

Table 6 Appendix summarizes the results of PLS modelling (by examining the le coefficient de correlation) showing the credibility of the hypothesis stipulating that the attraction of FDI in Tunisia is influenced by the location advantages (1) (T Statistics=4.985464>1.96 and coefficient=0.373316), reflecting that the Tunisian territory enjoys economic and political stability, infrastructure and qualified work force.

Our results show that FDI attraction is influenced by internalization advantages (T Statistics=4.120083>1.96 and coefficient=0.422313); however, results show non credibility of the hypothesis stipulating that FDI attraction is influenced by Ownership specific advantages (T Statistics=0.232430) and those of location (2) (T-Statistics=1.513603<1.96). In reference to Dunning, this result can be interpreted by a limited internal market and national companies with little advantages in terms of R&D, know-how, technology to compete with foreign companies with the same advantages in addition to an inappropriate governmental policy.

Conclusion

This study analysed the determinants of FDI’ attraction in Tunisia. Based on survey results and PLS regression, the empirical study applied to Tunisian economy indicates that traditional determinants (location factors) as well as the host country’s adopted strategies are not enough to attract FDI. Therefore, our results show that FDI attracted by Tunisia are based on incentives (support to FDI and taxation) that attract companies looking for cost reduction and risking to relocate from the Tunisian territory.

The government has therefore to launch a new strategy axed on the improvement of the investment climate and to put in place institutions that are able to value the advantages that the country has. FDI promotion policy in Tunisia rests on various bodies such as FIPA and the Institute of Competitiveness and Quantitative Studies. However, despite the significant deployed efforts, the government has to maintain the reforms’ dynamics. These institutions can put policies and strategies that aim at attracting FDI with new technology and direct FDI flows towards strategic sectors. In addition, the state can put in place an upgrading program for national companies to enable them to compete with foreign ones.

Appendix

| Table 1: Summary Of Information Collected By The Survey |

||||

| Latent variables | Manifest variables | Satisfaction | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not important | Very important | |||

| Ownership advantages | Intellectual property right | 15.4% | 23.1% | 0.74 |

| research and development | 23% | 46% | ||

| size of the main company | 61.5% | 15.4% | ||

| International Management Capacity | 0% | 15.4% | ||

| organizational effectiveness | 15.4% | 46.2% | ||

| New capital Search | 46.2% | 30.8% | ||

| Localisation advantages | political Stability | 0% | 47.5% | 0.86 |

| economic stability | 2.5% | 42.5% | ||

| quality infrastructure | 2.5% | 17.5% | ||

| Government support service | 2.5% | 20.5% | ||

| Country's legal framework | 0% | 50.0% | ||

| Transparent investment climate | 2.5% | 42.5% | ||

| Quality of life | 2.5% | 25.5% | ||

| physical security | 0.0% | 40.0% | ||

| Existence of foreign investors | 12.5% | 32.5% | ||

| Double taxation agreement | 5% | 37.5% | ||

| Cost of labor | 7.5% | 42.5% | ||

| Availability of qualified work hand | 5% | 37.5% | ||

| Raw material availability | 15% | 22.5% | ||

| local suppliers | 12.5% | 30.0% | ||

| Pr?sence de partenaire de co entreprise | 45% | 5% | ||

| Existing assets acquisition | 30% | 10% | ||

| Project specific investments | 40% | 2.5% | ||

| Currency exchange rate | 15% | 50% | ||

| Level of education | 12.5% | 57.5% | 0.63 | |

| Consumer protection | 17.5% | 32.5% | ||

| Internalisation advantages | Corruption poor governance | 15% | 37.5% | |

| Market imperfection | 20% | 32.5% | ||

| Market power | 25% | 30.0% | ||

| FDI attraction | Innovations protection policy | 7.5% | 37.5% | 0.73 |

| Research and development expenses | 10% | 37.5% | ||

| Help FDI | 5% | 52.5% | ||

| Free zone settings | 15% | 32.5% | ||

| Taxation | 2.5% | 32.5% | ||

| Market intervention | 7.5% | 30% | ||

| Table 2: Analysis Of Variance | |||||||

| Factors | Component | Initial values | Extraction Sums of squares of selected factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owneship avantages | Total | % of the variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of the variance | Cumulative% | |

| 1 | 2.774 | 55.474 | 55.474 | 2.774 | 55.474 | 55.474 | |

| 2 | 0.908 | 18.159 | 73.634 | ||||

| Location avantages | 1 | 2.742 | 34.272 | 34.272 | 2.434 | 30.427 | 30.427 |

| 2 | 2.062 | 25.773 | 60.145 | 2.369 | 29.618 | 60.045 | |

| 3 | 0.893 | 11.168 | 71.213 | ||||

| Internalisation avantages | 1 | 1.793 | 59.779 | 59.779 | 1.793 | 59.779 | 59.779 |

| 2 | 0.951 | 31.692 | 91.470 | ||||

| FDI attraction | 1 | 2.063 | 51.587 | 51.587 | 2.063 | 51.587 | 51.587 |

| 2 | 0.992 | 24.792 | 76.379 | ||||

| Table 3: Results Of The Pls Model: Demonstration Model | ||||||

| Internalisation | Manifest variables | Coefficient | AVE | Composite Reliability | R Square | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Ownership | International Management Capacity | 0.743060** | 0.570945 | 0.841055 | 0.769856 | |

| Organizational effectiveness | 0.704568** | |||||

| Research and development | 0.715095** | |||||

| New capital Search | 0.850803** | |||||

| Location L1 | Availability of qualified work hand | 0.653019** | 0.602412 | 0.856630 | 0.777775 | |

| Quality infrastructure | 0.709041** | |||||

| Economic stability | 0.846549** | |||||

| Political Stability | 0.873974** | |||||

| Location L2 | Existing assets acquisition | 0.703332** | 0.566962 | 0.836049 | 0.737809 | |

| Double taxation agreement | 0.561264** | |||||

| Pr?sence de partenaire de co entreprise | 0.837781** | |||||

| Project specific investments | 0.869642** | |||||

| Internalisation | Corruption poor governance | 0.450163** | 0.604652 | 0.604652 | 0.636899 | |

| Market imperfection | 0.941018** | |||||

| Market power | 0.851935** | |||||

| FDI | aide_ide | 0.720328** | 0.430230 | 0.430230 | 0.437713 | 0.733245 |

| Research and development expenses | 0.731010** | |||||

| Free zone settings | 0.470442** | |||||

| intervent_march | 0.678309** | |||||

| Innovations protection policy | 0.624563** | |||||

| Taxation | 0.675745** | |||||

| Table 4: Bootstrapping Results | |||||||

| Variables latentes | Variables manifestes | Coefficient | T student | AVE | Discriminant validity | Composite Reliability | R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La variable O | International Management Capacity | 0.74 | 4.93** | 0.577165 | 0.7596 | 0.84 | |

| organizational effectiveness | 0.70 | 5.23** | |||||

| research and development | 0.71 | 5.88** | |||||

| New capital Search | 0.85 | 7.11** | |||||

| La variable L1 | Availability of qualified work hand | 0.65 | 13.21** | 0.602098 | 0.7758 | 0.85 | |

| quality infrastructure | 0.70 | 12.35** | |||||

| economic stability | 0.84 | 15.11** | |||||

| political Stability | 0.87 | 18.95** | |||||

| Variable L 2 | aquisitio Existing assets acquisition | 0.70 | 5.70** | 0.569096 | 0.7543 | 0.83 | |

| Double taxation agreement | 0.56 | 3.59** | |||||

| joint venture Partner presence | 0.83 | 6.59** | |||||

| Project specific investments | 0.86 | 9.21** | |||||

| Variable I | Corruption poor governance | 0.45 | 0.602856 | 0.7764 | 0.60 | ||

| Market imperfection | 0.94 | 60.63*** | |||||

| Market power | 0.85 | 36.33** | |||||

| FDI | aide_ide | 0.72 | 10.77** | 0.525587 | 0.7249 | 0.43 | 0.437 |

| Research and development expenses | 0.73 | 9.67** | |||||

| Free zone settings | 0.47 | ||||||

| intervent_march? | 0.67 | 11.45** | |||||

| Innovations protection policy | 0.62 | ||||||

| taxation | 0.67 | 12.83** | |||||

| Table 5: Quality Criteria Of The Model | ||||

| AVE | Composite Reliability | R Square | Cronbachs Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDI Attraction | 0.490230 | 0.816516 | 0.437713 | 0.733245 |

| Internalization Advantages | 0.604652 | 0.809245 | 0.636899 | |

| Location 1 | 0.602412 | 0.856630 | 0.777775 | |

| Location 2 | 0.566962 | 0.836049 | 0.737809 | |

| Ownership Specific Advantages | 0.570945 | 0.841055 | 0.769856 | |

| Table 6: Validation Of The Internal Model | |||||

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | Standard Error (STERR) | T Statistics (|O/STERR|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avantages d’internalisation attraction des IDE | 0.422313 | 0.423570 | 0.102501 | 0.102501 | 4.120083 |

| Avantage de localisation1 attraction des IDE | 0.373316 | 0.381506 | 0.074881 | 0.074881 | 4.985464 |

| Avantage de localisation2 attraction des IDE | 0.118665 | 0.121253 | 0.078399 | 0.078399 | 1.513603 |

| Les avantages propres ? l’entreprise? attraction des IDE | 0.020523 | 0.034538 | 0.088300 | 0.088300 | 0.232430 |

References

Alaya, M., Nicet-Chenaf, D. & Rougier, E. (2007). Politique d’attractivité des IDE et dynamique de croissance et de convergence dans les Pays du Sud Est de la Méditerranée. Cahiers du GREThA n° 2007-06 Juin. 2007.

Anarfo, E.B., Agoba, A.M. & Abebreseh, R. (2017). Foreign direct investment in Ghana: The role of infrastructural development and natural resources. African Development Review, 29(4), 575-588.

Andreff, W. (2013). L’Etat mondialisateur survivra à la crise de la mondialisation, dans W. Andreff, dir., La mondialisation, stade suprême du capitalisme? Presses Universitaires de Paris Ouest, Nanterre, 295-313.

Asiedu, E. (2002). On the determinants of foreign direct investment to developing countries: Is Africa different? World development, 30(1), 107-119.

Blonigen, B.A. (2005). A review of the empirical literature on fdi determinants, Working Paper, NBER, n° 11299.

Bouoiyour. J., Hanchane, H. & Mouhoud, E. (2009). Investissements directs étrangers et productivité Quelles interactions dans le cas des pays du Moyen Orient et d’Afrique du Nord ? Revue économique, 60 (2009/1).

Buckley, P.J., Chen, L., Clegg, L.J. & Voss, H. (2018). Risk propensity in the foreign direct investment location decision of emerging multinationals. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(2), 153-171.

Calipha R., Tarba S. & Brock D. (2010). Mergers and acquisitions: A review of phases, motives and success factors. In: Cooper C. L. Et Finkelstein S. (coord.) Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, 9, Elsevier JAI, 1-24.

Cantwell, J. & Narula, R. (2001). The eclectic paradigm in the global economy. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 8(2), 155-172.

Chen C., Chang, L. & Zhang Y. (1995). The role of foreign direct investment in China’s post-1978 economic development. World Development, 23(4), 691-703.

Chen, G.S., Yao, Y. & Malizard, J. (2017). Does foreign direct investment crowd in or crowd out private domestic investment in China? The effect of entry mode. Economic Modelling, 61, 409-419.

Cui, L., Meyer, K.E. & Hu, H.W. (2013). What drives firms’ intent to seek strategic assets by foreign direct investment? A study of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.12.003

Dadzie, S.A., Owusu, R.A., Amoako, K. & Aklamanu, A. (2016). Do strategic motives affect ownership mode of foreign direct investments (FDIs) in emerging African markets? Evidence from Ghana. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60(3), 279-294.

Dunning et Narula. (1998). Multinationals and industrial competitiveness. Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK Northampton, MA, USA.

Dunning, J.H. (1995). Reappraising the eclectic paradigm in an age of alliance capitalism. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3), 461-491. http://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490183

Dunning, J.H. (1998). Location and the multinational enterprise: A neglected factor? Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1), 45-66.

Dunning, J.H. (2000). The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. International Business Review, 9(2), 163-190.

Dunning, J.H. (2001b). The Eclectic (OLI) Paradigm of international production: Past, present and future. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 8(2), 173-190.

Dunning, J.H. (2004). An evolving paradigm of the economic determinants of international business activity. In: J. L.C. Cheng & A. Hitt (Eds.), Managing multinationals in a global economy: Economics, culture, and human resources. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

Ghemawat, P. (2001). Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review, 79(8), 137-147.

Giuseppina, T. (2016). Foreign direct investment flows and the global economic crisis. Corporate Ownership and Control, 1 (4 Continued 1), 266-274.

Gorynia, M., Nowak, J., Tr?pczy?ski, P. & Wolniak, R. (2016). Determinants of FDI establishment mode choice of polish firms. The oli paradigm perspective. Argumenta Oeconomica, 37(2), 67-92.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R. & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Uppersaddle River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Johanson, J. & Vahlne, J.E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23-32.

Kim, S.K., Kim, M. & Kim, Y.H. (2012). The impacts of PTA formation on small economies’ tax competition for FDI inflows. Economic Modelling, 29(6), 2734-2743. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.08.003

Kinoshita & Campos, F. (2004). Estimating the determinants of direct investment inflow: How important are sampling and omitted variable biases, Williamson Institute Working Paper, 1-33.

Krugman, P. & Obstfeld, M. (1999). International economics, theory and policy. 4th edn.

Lien, Y.C. & Filatotchev, I. (2014). Ownership characteristics as determinants of FDI location decisions in emerging economies. Journal of World Business, 50(4), 637-650. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2014.09.002

Lim, S.H. (2008). How investment promotion affects attracting foreign direct investment: Analytical argument and empirical analyses. International Business Review, 17(1), 39-53. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2007.09.001

Lv, P. & Spigarelli, F. (2016) .The determinants of location choice: Chinese foreign direct investments in the European renewable energy sector. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 11(3), 333-356.

Makoni, P.L. (2015). An extensive exploration of theories of foreign direct investment. Risk governance and control. Financial Markets and Institutions, 5(2), (2CONT1), 77-84.

Métais E., Véry P. & Hourquet P. (2010). Le paradigme d’Uppsala: la distance géographique et l’effet de réseau comme déterminants des décisions d’acquisitions internationales (1990-2009) », Management International, 15(1), 47-58.

Morisset, J. & Olivier, L. (2002). Administrative costs to foreign investment in developing countries. Policy Research Working Paper, World Bank,Washington, DC.

Morisset, J. & Pernia, N. (2000). How tax policy and incentive affect foreign direct investment, working paper (2000).

Myna, A. (2017). Too small or too big to survive: Foreign direct investment and divestment in breweries. Journal of East-West Business, 23(4), 367-387.

Ogasavara, M.H. & Hoshino, Y. (2007). The impact of ownership, internalization, and entry mode on Japanese subsidiaries’ performance in Brazil. Japan and the World Economy, 19(1), 1-25. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2005.06.001

Prahalad, C.K. & Doz, Y. (1987). The multinational mission: Balancing local demands and global vision.

Ragozzino, R. & Reuer, J.J. (2011). Geographic distance and corporate acquisitions: signals from IPO firms. Strategic Management Journal, 32(8), 876-894.

Roussel, P., Durieu, F., Campoy, E. & Akremi, A. (2002). Méthodes d’équations structurelles: Recherche et applications en gestion, Paris: Economica, 21(2), 250-274.

Rui, H. & Yip, G.S. (2008). Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms: A strategic intent perspective. Journal of World Business, 43(2), 213-226. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2007.11.006

Siripaisalpipat, P. & Hoshino, Y. (2000). Firm-specific advantages, entry modes, and performance of Japanese FDI in Thailand. Japan and the World Economy, 12(1), 33-48. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0922-1425(99)00025-0

Stein, E. & Daude. C. (2001). Institutions, integration and the location of foreign direct investment. Washington, DC, United States: Inter-American Development Bank, Research Department. Mimeographed document, New York: The Free Press.

Strange, R. & Buckley, P.J. (2009). International diversification and the governance of multinational enterprises. Mimeo.

Tallman, S. (1991). Strategic management models and resource-based strategies among MNEs in a host market. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 69-83.

Tan, B. & Vertinsky, I. (1995). Strategic advantages of Japanese electronics firms and the scale of their subsidiaries in the US and Canada. International Business Review, 4(3), 373-386. http://doi.org/10.1016/0969-5931(95)00015-R

Wells et Wint. (1990). Marketing a country, promotion as a tool for attracting foreign investment. Foreign Investment Advisory Service Occasional Paper 1.