Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 1

Five-Sector Model of the Circulation of Resources, Income, and Expenditure in the Sharing Economy

Natalia Shilonosova, South Ural State University

Yulia Butrina, South Ural State University

Sergei Aliukov, South Ural State University

Abstract

The purpose of our study is to develop a new model of the circulation of resources, income, and expenditure in the sharing economy. To achieve this, we solved the following four tasks: 1. when studying the key aspects of the sharing economy, we revealed that the theory, methodology, and practice of the sharing economy have not yet been formed. 2. When studying the degree of penetration of online services into the economy based on a survey of young people, we found that the penetration degree is rather high. 3. When forming the new model of the circulation of resources, income, and expenditure in the sharing economy, we added a fifth sector - sharing aggregators - to the existing four-sector model, with further analysis of the interaction of all five sectors. 4. When modeling and detailing the interaction of resources, income, and expenditure in the sharing economy, we revealed that new real and cash flows are formed in the resulting model, which should be taken into account by the existing economic sectors, from households and to the outside world, to build new balances of the microeconomic and macroeconomic interaction.

Keywords

Sharing Economy, Sharing Aggregators, Sharing Services, Circulation of Resources, Income, Expenditure.

Introduction

Currently, the sharing economy as a collaborative consumption economy is becoming more widespread. Sharing is defined as any activity related to the additional use of property held by consumers, as well as obtaining certain benefits during this use. Various online services have been created and successfully develop within the framework of the global network and platform infrastructure (Lymar, 2018; Sadovskaya, 2018, Rinne, 2019).

The concept of collaborative consumption in economic science was highlighted by Rachel Botsman and Roo Rogers, the co-authors of the book “What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption” (Botsman & Rogers, 2010) and Rachel Botsman’s presentations at the 2010 TED conference. A new socio-economic model, which should revolutionize into the consumption of goods and services, was developed.

In 2011, the sharing economy was included in Time Magazine’s List of Ideas That Will Change the World Soon (Walsh, 2011).

The idea of ??the collaborative consumption economy is reflected in the function of traditional business, which leads to its transformation and increased efficiency. The idea is implemented by two methods. The first method involves the transition of online platforms which were an e-commerce platform for the owners of any property (individuals) and customers (individuals) but did not work efficiently enough, to an online service representing the interests of a company (legal entity) owning the assets leased to the same customers. Such platforms include, for example, Lyft, Rent the Runaway, Zipcar. This method reflects the evolutionary transformation of the business and is associated with the quantitative optimization of resources.

The second method involves companies using the sharing principles and creating specialized online platforms. Such companies include, for example, large hotel chains such as Hilton, Radisson, and carmaker Ford. This method reflects the revolutionary transformation of traditional business and is associated with the qualitative optimization of resources. The difference between these two methods lies primarily in the fact that in the first method, online platforms become an addition to the existing business model, while in the second method; online platforms are the basis of a new business model, according to which a modern business is built. This transition is mainly preconditioned by the fact that consumers are more and more inclined towards the on-demand economy (Yeung, 2015). Therefore, companies from different countries are delving into this hybrid business model.

However, there is a disjointed view of the mechanisms and infrastructure of the function of the sharing economy. A holistic approach should include stable terminology, a description of the principles and socio-economic models of sharing relationships at the micro and macro levels, the psychology of sharing relationships, issues of state regulation (legislation, taxes and social contributions, benefits), operation of companies owing online platforms, insurance, technical and technological aspects of the online sharing service functioning, self-employment, ecology, logistics, transformation of the traditional business, social effects, financial literacy, pricing, transaction costs, etc.

The purpose of the work is to develop a new model of the circulation of resources, income and expenses in the conditions of the sharing economy.

Tasks to be solved.

1. Study and identification of key aspects of the sharing economy from theoretical sources.

2. Studying the degree of penetration of online services into the economy based on a survey of young people and determining the prospects for the development of the sharing economy.

3. Formation of a new methodology for the circulation of resources, income and expenses in the conditions of a shared economy by building a general model and describing real and cash flows through shared aggregators.

Methodology

Key Aspects of the Sharing Economy

We should immediately note that the practical establishment of the sharing economy is represented by the rapid development of car-sharing and rental housing, and the basis of such an economy in business is online platforms (Richardson, 2015).

We will highlight five key aspects of the sharing economy:

Scientific works show that car and housing sharing programs (overnight stop, travels) provide people with short-term access to personal property without the higher costs and responsibility which may be connected with ownership and, importantly, with a rather high level of service needs (Birdsall, 2014). Authors have considered non-traditional, non-institutionalized trends in the sphere of traveling, which undermine basic tourism, providing travelers with a wider range of alternatives, including home exchanges (Forno & Garibaldi, 2015).

1. Some authors view sharing as one of the ways to protect the environment. Reusing things can change the output and reduce the burden on nature since less non-renewable resources will be consumed (Kessler, 2015; Teubner, 2014).

2. An important aspect of sharing relations is trust, an increase in the economic importance of interpersonal aspects, and direct transactions between households (Chica et al., 2017; Hawlitschek et al, 2016). Mistrust risks are associated with insurance issues (Weber, 2014).

3. The issues of sustainability of the sharing economy, the prosperity of the entities involved in it, and social equality are important for the economy (Heinrichs, 2013).

4. It is essential that the sharing economy provides people with an additional opportunity to find temporary work, gain extra income, improve social interaction, and receive access to information resources, which are otherwise unable to be achieved (Dillahunt & Malone, 2015). Through various information channels, unemployed people or people experiencing financial difficulties will learn about the sharing economy potential, which may increase employment among these population groups.

5. The sharing economy had the tools to restore the global economy after the crisis of 2008-2010 (Pais & Provasi, 2015).

We will give a brief description of the above aspects of the sharing economy in Table 1.

| Table 1 Key Aspects of the Sharing Economy | ||

| ? | Key aspects | Benefits |

| 1 | Property | Reducing costs, reducing the importance of ownership |

| 2 | Use | An increase in the frequency, improving environmental |

| 3 | Interpersonal relationships | Increasing trust between people, increasing the importance of social ties |

| 4 | Economic growth | Increasing sustainability, improving the social environment |

| 5 | Employment | Additional income, reduced unemployment |

Table 1 shows that all five key aspects of the rank economy imply benefits, while the first three aspects relate to the level of microeconomics and the fourth and fifth aspects characterize benefits at the macroeconomic level.

The importance of the collaborative consumption economy determines the efficiency of economic development, while the legal regulation of the collaborative consumption economy is essential. This includes solving legal problems and regulating the relations between property owners and users transferred to sharing, labor relations, and other legal issues in such segments as car-sharing and ride-sharing, food sharing, home exchange, etc. (Bychkov, 2019).

The development of the digital economy in Russia is a key factor of economic growth and improving the quality of life (Sologubova, 2018). The transformation of property relations is connected with profound changes and the appearance of a network of interaction (Maryganova, 2018). The influence of the sharing economy on market relations is significant (Pykhteeva & Vinogradov, 2018), while the sharing economy undermines the competitive foundations of the market (Litvinov, 2018). At the same time, the sharing economy is a new business model (Yuldashev, 2018).

We should highlight a specific feature of the modern economy: the phenomenon of economic uberization (Tagarov, 2019). Let us highlight in particular the phenomenon of sharing economy as a new promising engine of tourism in Russia (Eremeeva et al., 2018). New marketing tools are being developed to promote online travel services (Graf & Savelieva, 2018). There is an innovative transformation of society due to the increasing role of information and knowledge and a fundamental change in the infrastructure and life in the smart cities format from the perspective of sharing economy (Komleva et al., 2016). The issues of economic socialization of an individual and the use of the value approach are becoming important in the collaborative consumption economy (Drobysheva, 2013). The economic culture of the metropolis is changing (Raskov et al., 2017).

Some features of the sharing economy development in Russia have been outlined (Gabrielyan, 2018) and the fundamentals of the collaborative consumption economy have been developed (Golovetsky & Grebenik, 2017). The sociocultural futurological phenomenon of collaborative consumption has been highlighted (Kuzmina, 2017) and several psychological and legal problems of sharing have been identified (Pykhteeva & Vinogradova, 2018).

There have been attempts to determine the parameters of the collaborative consumption economy in 2016-2019, as well as long-term forecasts. For example, McKinsey Company’s survey determines the number of people employed in this area. In 2016, 30% of the working-age population of the United States had additional part-time jobs, including those connected with sharing (Manyika et al., 2016).

It is generally very difficult to quantify the parameters of the sharing market since the necessary methodology and mechanism for recording and regulating this phenomenon does not exist. Nevertheless, the scales can be measured indirectly. According to PwC’s estimates, in 2015, there were over 300 companies in Europe established in different sectors of the collaborative consumption economy. Their total annual income amounted to over 4 billion Euros. In the United States, there were four times more such companies at that time (Yip, 2017).

The sharing economy is associated with the phenomenon of gigonomics or gig economy, which includes uber-like services representing part-time work opportunities for the unemployed (later on they fall into the category of freelancers), hearing-impaired, and other people (Adactilos et al., 2018). New digitalization contours have been formed (Revenko, 2018). The economic development sustainability is determined through the development of the collaborative consumption economy (Stavtseva, 2018). Various positive and negative aspects of the sharing economy have been determined (Ulyanova & Arzharova, 2015). The function of online platforms is determined from the standpoint of the issues of the technology, efficiency and areas for development (Sena, 2015).

The results of the private car rental development and the possible decrease in demand and job loss have been analyzed (Green, 2014). The issue of the hybrid nature of the sharing economy as an economy of interaction between the market and non-market economy, which requires appropriate approaches to the development of the collaborative consumption economy, has been investigated (Scaraboto, 2015). The relatively new network business has already been characterized as a traditional business and new models for its construction are being formed (O’Reilly, 2015).

The new facts of the economic life in the sphere of collaborative consumption have been studied, accumulated, and generalized, the research vocabulary has been developed to some extent, a special object has been crystallized, and the basic theoretical and methodological foundations of the sharing economy have been formed. However, the theory, methodology, and practice of the sharing economy have not yet been formed. That is, intensive development of the theory of sharing economy is currently underway, and this process is far from completion.

Analysis of the Degree of Penetration of Online Services into the Economy

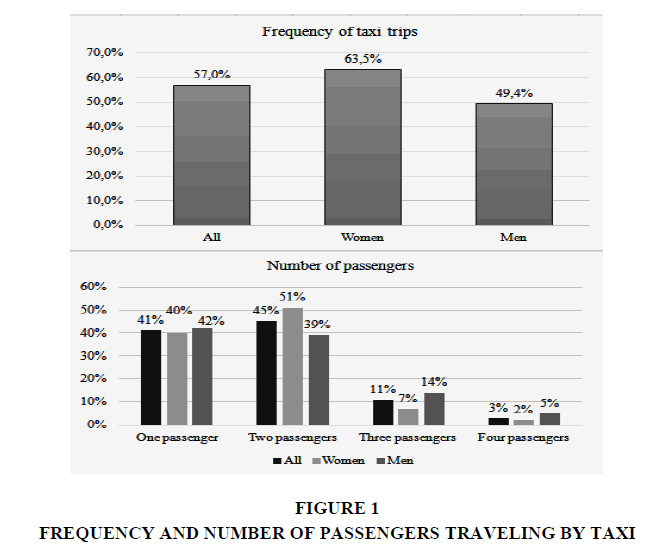

To understand the degree of penetration of online services into the economy and the development of sharing, we chose the city taxi segment, operating according to the collaborative consumption concept. The study was carried out through a survey of 179 people with an average age of 20 years old. The survey was conducted in writing among students in October 2019. The survey is called “Satisfaction with Taxis” and concerns the economic use of Uber/ Yandex taxi in the city of Chelyabinsk, Russia. The survey contains 13 questions grouped in three pools: (1) travel conditions, (2) extra charges, and (3) discounts. We proposed several answers and asked the respondents to choose one. The respondents included 83 men (46.4%) and 96 women (53.6%). Let us consider the results obtained by the polls. Figure 1 shows the answers to the two questions of the first pool “Travel Conditions”.

We can see from Figure 1 that to the first question “Do you often take a taxi using online platforms? ” 57% answered positively, which means that more than half of the respondents have already actively used the platform. Moreover, women use these platforms more (63.5%) than men (49.4%). This means that online platforms have actively entered their lives. The answers to the second question “How many passengers are usually in the taxi, including you?” showed that the usual number of passengers in the taxi is two (47%) or even one (40%). This means that economies of scale do not play a major role, the trip itself is important and, moreover, taxi trips can be considered as a living standard similar to having a car with a personal driver. Figure 2 shows the answers to the next two questions of the first pool.

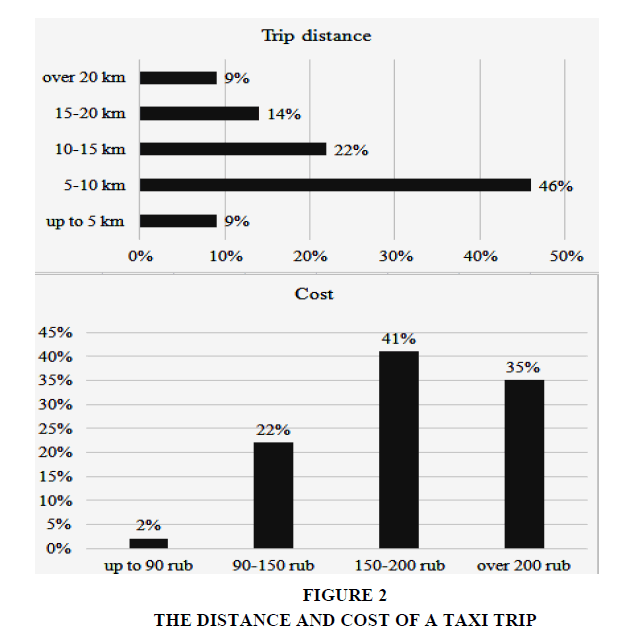

Figure 2 shows that the answers to the question “What distance do you most often need to travel by taxi?” showed that the most common trip distance is 5-10 km (46%); 48% of women and 43% of men gave such an answer. This means that it is not the speed of the trip, but the comfort of traveling that matters. The fourth question “What is the usual cost of this taxi ride?” shows that the most frequent answer is 150-200 rubles (40% of the respondents answered so), which gives us the correct economic understanding of costs in this survey. As for the fifth question “To what amount can you assess the difference in the “Economy” and “Comfort” categories?”, the most common answer is 50 rubles (39% of the respondents), but since the answer is related to the distance and the cost of the trip, there are variants of answers differing both upward and downward. This question is can be related to the next two pools by the cost estimates through the system of extra charges and discounts.

Summing up the pool “Travel Conditions”, we can note that online taxi platforms have become widespread in our lives, they are easy and convenient to use for traveling individually and for long distances.Pool 2. Extra charges. We selected the two most common extra charges and proposed two new services for which charges are expected. Table 2 shows the answers for questions 6 through 9.

| Table 2 Survey Results Covering the Second Pool Extra Charges, % | |||

| Name | Share of answers, total | Including | |

| answered by women | answered by men | ||

| How much are you ready to pay for special conditions (for example, rush hour or rain)? | |||

| ?) 0 rub | 43 | 42 | 45 |

| b) 30 rub | 28 | 30 | 25 |

| c) 50 rub | 26 | 26 | 25 |

| d) 80 rub | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| e) 110 rub | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| How much are you ready to pay for reducing the taxi waiting time from 15 minutes to 5 minutes? | |||

| ?) 0 rub | 55 | 49 | 60 |

| b) 30 rub | 36 | 46 | 25 |

| c) 50 rub | 7 | 5 | 10 |

| d) 80 rub | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| e) 110 rub | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| How much do you agree to pay extra for choosing the driver’s profile (gender, age)? | |||

| ?) 0 rub | 78 | 73 | 84 |

| b) 30 rub | 16 | 20 | 12 |

| c) 50 rub | 6 | 7 | 4 |

| d) 80 rub | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| e) 110 rub | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| How much do you agree to pay extra for additional selectable parameters (for example, a special aroma, favorite music, opening the door, etc.)? | |||

| ?) 0 rub | 69 | 67 | 71 |

| b) 30 rub | 20 | 24 | 17 |

| c) 50 rub | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| d) 80 rub | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| e) 110 rub | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 2 shows that most of the respondents do not welcome extra charges, especially for new, unknown services. However, in each question there is a cost choice of extra charges; further research can deal with the analysis of this choice made by individual respondents.

Pool 3. Discounts. As opposed to extra charges, for varieties of discounts are also considered, both by the type of the existing discount offers and new ones. Table 3 shows the answers for questions 10 through 13.

| Table 3 Survey Results Covering the Third Pool "Discounts", % | |||

| Name | Share of answers, total | Including | |

| answered by women | answered by men | ||

| What discount rate do you think is appropriate for having no luggage? | |||

| ?) 0 % | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| b) 5 % | 40 | 42 | 37 |

| c) 7 % | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| d) 10 % | 13 | 16 | 10 |

| e) 15 % | 19 | 15 | 24 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| What discount rate do you think is appropriate for the young passenger age (up to 22 years)? | |||

| ?) 0 % | 31 | 17 | 27 |

| b) 5 % | 31 | 35 | 27 |

| c) 7 % | 13 | 10 | 16 |

| d) 10 % | 13 | 18 | 7 |

| e) 15 % | 22 | 20 | 23 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| What discount rate do you think is appropriate for a form of payment convenient for the driver (for example, cash or card)? | |||

| ?) 0 % | 21 | 21 | 22 |

| b) 5 % | 41 | 42 | 41 |

| c) 7 % | 11 | 16 | 5 |

| d) 10 % | 15 | 10 | 19 |

| e) 15 % | 12 | 11 | 13 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| What discount rate do you think is appropriate for a subscription for 5 upcoming trips? | |||

| ?) 0 % | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| b) 5 % | 13 | 10 | 16 |

| c) 7 % | 16 | 23 | 8 |

| d) 10 % | 30 | 32 | 28 |

| e) 15 % | 37 | 33 | 42 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 3 shows that discounts are welcome, especially for a subscription. Where most of the respondents chose a 5-percent discount for young age, the form of payment, and lack of luggage, the majority chose a 15-percent discount for the five-trips subscription.

Summing up the survey, we can note that the degree of penetration of online services into the economy is rather high. Consumers do not only use online services but also understand them well, having their own wishes and preferences in terms of economic characteristics.

The Formation of a Five-Sector Model of the Circulation Of Resources, Income, and Expenditure

The basic idea of the sharing economy is that it is more profitable to pay for rent than for a whole purchase. Attempts have been made to build different models, such as the model of interaction between users of the sharing economy Tagarov (2018), the model of interaction through the justification of the reasons for resorting to the sharing economy Golovetsky & Grebenik (2017). Let us note some of the problems of the sharing economy that are characteristic of these models: a low level of trust in institutions in general and in social services in particular; the presence of information inequality between age groups and localities of different sizes; the lack of adaptation of existing state regulatory measures to the realities of a peer-to-peer digital economy.

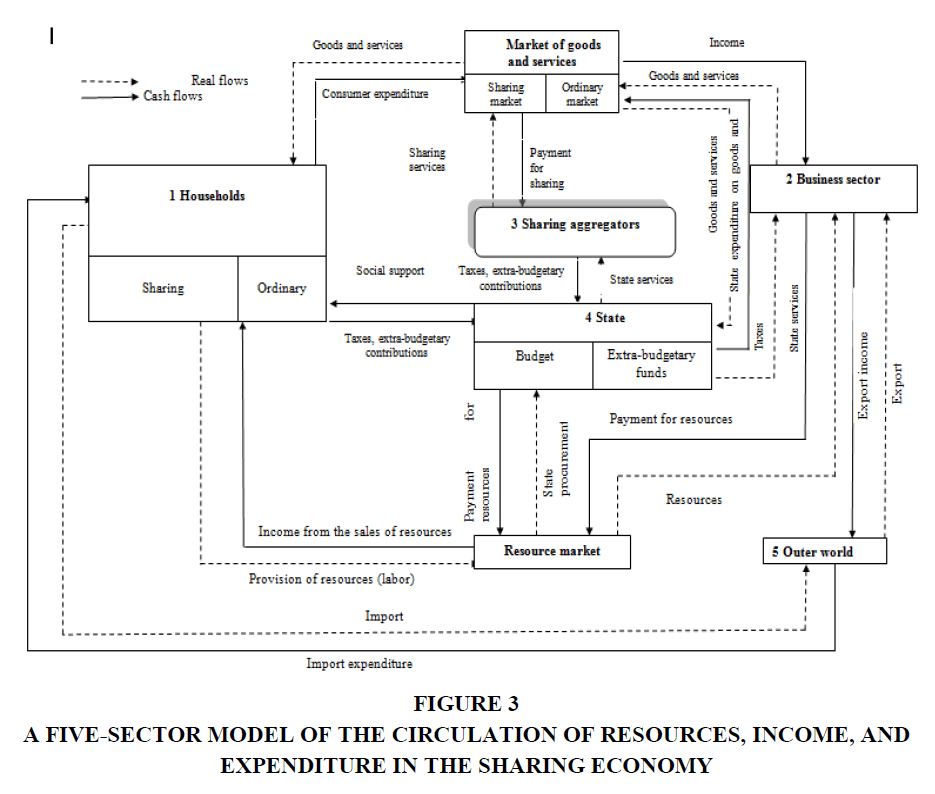

Let us consider how the sharing economy changes the circulation of resources, income, and expenditure. First of all, we should note that four significant sectors are distinguished in the well-known circulation model: households, business, state, and foreign (the outside world). This model can be considered as a two-sector (households and business), three-sector (by adding the state), four-sector (by adding the outside world). Each of the models has two markets: a resource market and a market of goods and services.

Due to the development of a new segment—the sharing economy—the market of goods and services should be divided into two types based on the availability of an information platform: the ordinary market (without a platform) and the sharing market (with a platform). Notably, these two markets will exist in the economy; a full shift to the sharing economy will not occur in the near future. In the resource market, similar to the market of goods and services, a new segment is appearing—the sharing economy. Therefore, the resource market also has to be divided into two types based on the availability of a platform: the ordinary market (without a platform) and the sharing market (with a platform). Since sharing aggregators have the information platform, they should be introduced into the model.

We propose to supplement the existing four-sector model with a fifth sector, thus making the model more complex. Let us consider the new five-sector model of the circulation of resources, income, and expenditure.

1. Households. Let us introduce a new feature in household classifications—by the availability of sharing property. Consequently, households can be divided into two types: owners of sharing property (those who have such property) and consumers of sharing property (those who do not have such property). We should say that there are households who do not own any sharing property as well as households who own several forms of sharing property (for example, a car and a tool).

2. Business sector. This is a sector of interaction. We should emphasize here that a sharing service is just a service. Goods and works are in the business sector, and the sharing service is attached to them. Business becomes the second nature of any person who begins to realize himself/herself not as a “screw” in a business environment (for example, in coal mining or manufacturing of a weaver loom), but as a person of interaction, helping other people, satisfying their needs, and at the same time gaining rewards (income) for it. This is very important when maintaining an income and expenditure balance.

3. Sharing economy aggregators. It is assumed that aggregators operate in different markets, although they can also combine them in the form of providing a “turnkey” service. For example, offering a service to find housing and a car to travel to the chosen location. When implementing the win-win strategy, a synergy effect may occur, and the sharing service becomes uniform, and, therefore, more complete. Moreover, it is very important for a chain of different necessary options from the list to appear; the service becomes complete (for example, by adding guide services to housing and transport services). We should note here that sharing economy aggregators can become tax agents for the sharing property owners. As a result, sharing aggregators can pay taxes from the sharing property income, just like they charge a fee for the provided sharing services.

4. Public sector. The state is represented in the form of both budgetary and extra-budgetary income, and expenditure.

5. Foreign economic sector.

Figure 3 shows the five-sector model of the circulation of resources, income, and expenditure in the sharing economy. The model is an economic circulation, as it shows the circular movement of resources, goods, and services (real flows are counterclockwise lines) ensured by the oncoming movement of cash flows (cash flows are clockwise lines).

Figure 3: A Five-Sector Model of the Circulation Of Resources, Income, and Expenditure in the Sharing Economy

Figure 3 shows that in the resource market, households offer their resources to the business sector, which presents a demand for these resources. Resource prices are formed as a result of the supply and demand interaction in this market. When prices are formed, households provide resources to the market. Further, the market provides the resources to the business sector, which converts them into goods and services, and then delivers them to the market of goods and services (real flow is shown by solid counterclockwise lines). The business sector, in turn, bears the expenses of paying for the resources (cash flow), which are income to the households from the sale of the resources (dashed clockwise lines). In this model, sharing aggregators appears, which interact with the sharing market, both in providing services and in paying for them.

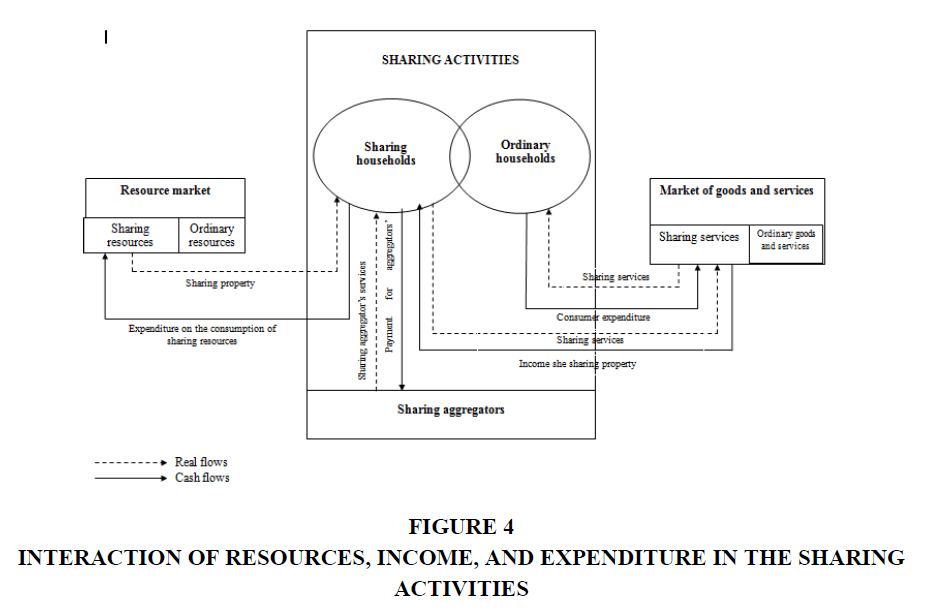

Modeling and Detailing the Interaction of Resources, Income, and Expenditure in the Sharing Economy

A more detailed diagram of the interaction of resources, income, and expenditure in the sharing activities is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows that in the resource market, the sharing segment provides the sharing property to the sharing households, which in turn provide sharing services to the market of goods and services (the sharing services segment). This segment provides sharing services to ordinary households (counterclockwise). The ordinary households bear consumer expenses and pay for them in the services market, which generates income from the sharing property to sharing households (clockwise). Sharing aggregators provide the services of a sharing aggregator to the sharing households and receive payment from the sharing households. Additionally, the sharing households incur expenses on the consumption of sharing resources (sharing property).

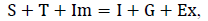

Let us present the condition of the general economic equilibrium in the well-known four-sector model in the form of an equation - formula (1), which reflects leaks (outflows) and injections (inflows).

....(1)

....(1)

where S is savings of households;

T—tax payments net of transfers;

Im—expenditure on importing goods and services;

I—investment expenditure;

G—public expenditure;

Ex—income from exporting goods and services.

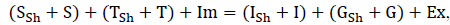

When sharing (the five-sector economy model) appears, individual elements of the economic equilibrium equation are transformed - formula (2).

.....(2)

.....(2)

where SSh is the savings of sharing households;

TSh—tax payments related to sharing activities, net of transfers;

ISh— investment expenditure related to sharing;

GSh—public expenditure on sharing.

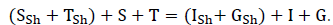

Considering the microlevel (Fig. 4), the equilibrium model can be represented in the form of formula (3), which includes sharing (arranged in brackets) and traditional outflows and inflows.

......(3)

......(3)

Thus, sharing aggregators, as interaction participants, regulate sharing activities, i.e., new flows appear and should be taken into account by all economic sectors, from households to the state and the outside world. New conditions for the macroeconomic equilibrium are being formed, which should be studied in the future. Instead of one basic macroeconomic formula, there are two (microeconomic and macroeconomic), which show how it is most efficient to balance sharing households and the state.

The scientific contribution of the research is to determine a new model of the circulation of resources, income and expenses in the conditions of the sharing economy, as well as to analyze the degree of penetration of online services into the economy.

1. A study of the key aspects of the sharing economy showed that the theory, methodology, and practice of the sharing economy have not yet been formed.

2. An analysis of the degree of penetration of online services into the economy shows a fairly high degree of penetration. Consumers don’t only use online services but are also adept at using them, having their own wishes and preferences in terms of economic characteristics.

3. The formation of the five-sector model of the circulation of resources, income, and expenditure is attributed to the development of a new fifth sector—sharing aggregators. The addition of sharing aggregators to the existing well-known four-factor model of circulation results in the appearance of a new understanding of the economic circulation of resources, goods, and services with the oncoming movement of cash flows.

4. Modeling and detailing the interaction of resources, income, and expenditure in the sharing economy characterizes the economic equilibrium condition reflecting leaks (outflows) and injections (inflows). This condition shows how it is possible to efficiently balance sharing households and the state.

5. In the current conditions of the restrictive measures related to the threat of COVID-19, the importance of the objective conditions for the penetration of online services into the economy and the development of the sharing economy is increasing, the actualization of sharing aggregators is strengthening, and the relations with all five sectors of the circulation of resources, income, and expenditure are consolidating.

References

- Adactilos, A.D. Chaus, M.S., & Moldovan, A.A. (2018). Sharing economy. Economics, 4 (36), 95-100.

- Birdsall, M. (2014). Carsharing in a sharing economy. Institute of Transportation Engineers, 84(4), 37.

- Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2010). What’s mine is yours. The rise of collaborative consumption.

- Bychkov, A.I. (2019). Legal regulation of the collaborative consumption economy: monograph. Infotropic, 136 p.

- Chica, M., Chiong, R., Adam, M. T., Damas, S., & Teubner, T. (2017). An evolutionary trust game for the sharing economy. In 2017 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) (pp. 2510-2517). IEEE.

- Dillahunt, T.R., & Malone, A.R. (2015). The promise of the sharing economy among disadvantaged communities. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2285-2294).

- Drobysheva, T.V. (2013). Economic socialization of a personality: Value approach: monograph. Social Psychology and Society, 19.

- Eremeeva, M.M., Mashyanova, D.A., & Klinskikh, A.A. (2018). The phenomenon of sharing economy as a new promising engine of tourism in Russia.

- Forno, F., & Garibaldi, R. (2015). Sharing economy in travel and tourism: The case of home-swapping in Italy. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 16(2), 202-220.

- Gabrielyan, O.R. (2018). Features of the sharing economy development in Russia. Socio-Economic Management: Theory and Practice, 4 (35), 36-37.

- Golovetsky, N.Y., & Grebenik, V.V. (2017). Fundamentals of the collaborative consumption economy. Bulletin of Moscow University, 4 (23), 21-26.

- Graf, S.V. & Savelyeva, E.A. (2018). Sharing economy and kakonomics: new marketing concepts in tourism. Green, J. (2014). How the sharing economy is changing the face of the automotive industry. Automotive Industries AI, 194 (12).

- Hawlitschek, F., Teubner, T., Adam, M.T.P., Borchers, N.S., Möhlmann, M., & Weinhardt, C. (2016). Trust in the sharing economy: An experimental framework. International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2016, December 11-14, Dublin, Ireland, pp. 1 -14.

- Heinrichs, H. (2013). Sharing economy: A potential new pathway to sustainability. GAIA, 22 (4), 228-231.

- Kessler, S. (2015). The sharing economy is dead, and we killed it. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/3050775/the-sharing-economy-is-dead-and-we-killed-it#3

- Komleva, N.V., Musatova, Z.B., & Danchenok, L.A. (2016). Smart technologies in the innovative transformation of society.

- Kuzmina, T.V. (2017). The sociocultural futurological phenomenon of collaborative consumption: Causes of occurrence, signs, effects.

- Litvinov, A.M. (2018). Sharing economy - a special kind of competition or undermining the competitive foundations of the market?. Regulatory Impact Assessment: A Strategic Partnership of the Government, Business, and Non-Profit Companies: Proceedings of the International Youth Scientific and Practical Conference, Ural State University of Economics, pp. 149-152.

- Lymar, E.N. (2018). The economy of collaborative consumption in modern Russia. Economic Sciences, 63, 67-72.

- Manyika, J., Lund S., Bughin J., Robinson K., Mischke J., & Mahajan D. (2016). Independent work: Choice, necessity, and the gig economy.

- Maryganova, E.A. (2018). Prospects for the transformation of property relations in the digital economy conditions.

- O’Reilly, ?. (2015). Networks and the nature of the firm. Aug 14 https://wtfeconomy.com/networks-and-the-nature-of-the-firm-28790b6afdcc

- Pais, I., & Provasi, G. (2015). Sharing economy: A step towards the re-embeddedness of the economy? Stato e Mercato, (105), 347-377.

- Pykhteeva, I.V., & Vinogradov, A.V. (2018). Prospects for the development of the sharing economy and its impact on market relations. Proceedings of conferences of Humanities Scientific Research Institute “Natsrazvitie”. August: a collection of selected articles. pp. 117-124.

- Raskov, D.E., Kadochnikov D.V.; Kudrin, A.L., Pogrebnyak, A.A., & Shirokorad, L.D. (2017). Economic culture of the metropolis.

- Revenko, N.S. (2018). New contours of digitalization abroad and in Russia: collaborative consumption economy.

- Richardson, L. (2015). Performing the sharing economy. Geoforum, 67, 121-129.

- Rinne, ?. (2019). 4 big trends for the sharing economy in 2019.

- Sadovskaya, A.G. (2018). Main aspects of the sharing economy functioning. Bulletin of Modern Research, 4(24), 252-254.

- Scaraboto, D. (2015). Selling, sharing, and everything in between: The hybrid economies of collaborative networks. Journal of Consumer Research, 42 (1), 152-176.

- Sena, P. (2015). How Uber is rewiring your customer’s brain and what you can do about it.

- Sologubova, G.S. (2018). The components of digital transformation. Urait, 218.

- Stavtseva, T.I. (2018). Sustainable economic development: closed-loop economy and collaborative consumption economy. Scientific and Practical Electronic Journal “Alleya Nauki”, 7 (23).

- Tagarov, B.Z. (2018). The phenomenon of business uberization and its boundaries. Creative Economy, 13(1), 93-104.

- Teubner, T. (2014). Thoughts on the sharing economy. Proceedings of the International Conferences on ICT, Society and Human Beings 2014, Web Based Communities and Social Media 2014, e-Commerce 2014, Information Systems Post-Implementation and Change Management 2014 and e-Health 2014 - Part of the Multi-Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, MCCSIS 2014, pp. 322-326.

- Ulyanova, N., & Arzharova, Y. (2015). Mr. and Mrs. sharing. Business Journal, 1, 18-23.

- Walsh, B. (2011). 10 ideas that will change the world. Retrieved from http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2059521_2059717_2059710,00.html

- Weber, T.A. (2014). Intermediation in a sharing economy: Insurance, moral hazard, and rent extraction. Journal of Management Information Systems, 31 (3), 35-71.

- Yeung, K. (2015). 3 ways brands can compete with the sharing economy. Retrieved from https://venturebeat.com/2015/10/05/3-ways-brands-can-compete-with-the-sharing-economy/

- Yip, P. (2017). How to grow a business in 190 markets: 4 Lessons from Airbnb.

- Yuldashev, O.U. (2018). Innovations of the marketing models of Russian companies in the epoch of digital transformation: a collective monograph. St. Petersburg: Publishing House of St. Petersburg State University of Economics.