Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 5

Financial Knowledge and Entrepreneurial Intention among Iranian University Students: A Gender Analysis

Nematollah Shiri, Ilam University

Behrooz Badpa, Ilam University

Rachel S. Shinnar, Ilam University

Citation Information: Shiri, N., Badpa, B., Shinnar, SR., (2023) Financial Knowledge And Entrepreneurial Intention Amongiranian University Students: A Gender Analysis. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 27(5), 1-14

Abstract

Prior research has examined various antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions; however, the importance of financial literacy has not received much attention, especially in the context of developing economies. This study examines the role of financial literacy in shaping entrepreneurial intentions among Iranian university students majoring in accounting. More specifically, this study examines three dimensions of financial knowledge regarding spending, saving and giving. Based on the responses of 504 students, findings suggest that knowledge regarding saving matters in shaping entrepreneurial intentions among university graduates regardless of gender. In addition, knowledge regarding spending was found to impact entrepreneurial intentions among female respondents only, while the giving dimension did not impact entrepreneurial intentions for the male nor female respondents. Implications for research and practice are discussed

Keywords

Financial Literacy, Entrepreneurial Intentions, Gender.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a critical driver of economic growth and development, job creation and reduction of unemployment/underemployment, and a vehicle for alleviating poverty (Cheng et al., 2021; Hussaina et al., 2017; Shiri et al., 2016; 2017; Thurik et al., 2008; Mbhele & Qhwagi, 2023). Given high rates of unemployment among university graduates in Iran, policymakers, public officials, and planners seek to encourage graduates to start new businesses (Ahamad and Seymour, 2008; Mirzasafi et al., 2011; Shiri et al., 2021). Research findings suggest that financial literacy can help individuals develop saving habits (Sabri and MacDonald, 2010) as well as contribute to entrepreneurial financial skills such as market knowledge and understanding of the financial resources available. Thus, financial literacy may also drive entrepreneurial intentions (Li and Qian, 2020) and lead to the establishment of new businesses or the expansion of existing ones (Rikwentische et al., 2015). Indeed, some studies suggest that financial literacy and saving impact individual entrepreneurial intentions (Hasan et al., 2020; Li and Qian, 2020). Individuals with higher levels of financial literacy, are found to be more interested in entrepreneurship (Aldi et al., 2018; Song et al., 2020), better at exploiting opportunities (Glaser and Walther, 2013), and more likely to develop entrepreneurial intentions (Ahmad et al., 2019; Bilal et al., 2021).

However, research on the ways in which financial literacy contributes to entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors is limited (Ahmad et al., 2019; Shafinar et al., 2015; Li and Qian, 2020), especially in developing countries (Alshebami & Al Marri, 2022). In addition, there is a significant gap in financial literacy levels between developed and developing countries (Bilal et al., 2021; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011), especially in the Arab world (The World Bank, 2016). In Iran, (Klapper, Lusardi & Van Oudeusen, 2014) consider only 20% of the adult population to be financially literate. Because financial literacy can be developed, much value may be gained from identifying whether financial literacy matters in strengthening entrepreneurial intentions.

In this study we seek to understand the ways in which financial literacy among accounting students in Iran is related to their entrepreneurial intentions in terms of post graduation employment. Given the important role that gender plays in occupational choice, we also examine whether gender moderates the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intentions.

Theoretical Framework

The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) suggests that intention is a good predictor of behavior. Krueger, Reilly and Carsrud (2002) support the notion that intentions are the single best predictor of any planned behavior, including entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs make decisions about starting a new business in a purposeful and planned manner (Davidsson, 1995) and entrepreneurial intentions consciously direct attention, experience, and behavior among entrepreneurial minded people (Bird, 1988). Past research has identified different variables that can shape an individual’s entrepreneurial intentions such as personality (Murad et al., 2021; Jiatong et al., 2021) entrepreneurial self efficacy (Baughn et al., 2006; Bullough et al., 2014; de Bruin et al., 2007), having an entrepreneur in one’s family (Trunk and Dermol, 2015), gender (Shinnar et al., 2012), and entrepreneurship education (Boubker et al., 2021; Kolvereid and Moen, 1997; Liñan et al., 2011). An additional variable that has been identified as an antecedent to entrepreneurial intentions, but has so far received limited research attention, is financial literacy (Shi, 2012).

Ajzen’s (1991) theory of planned behavior has been frequently applied in the study of entrepreneurial intentions ( Díaz Jiménez, 2010; Liñan, 2008; Liñan Chen, 2009; Liñan et al. 2010; Moriano et al. 2011) to explain the antecedents that shape individual s intentions to pursue entrepreneurship. Three cognitive antecedents identified in the theory are considered reliable predictors of EI , explaining one third to nearly half of the variation in EI in various studies (Kolvereid, 1996; Liñan Chen, 2009; v an Gelderen et al., 2008). These include: personal attraction, subjective norm, and perceived beh avioral control . Personal attraction refers to the attitude a person holds about the behavior in question. Subjective norm is defined as the “likelihood that important referent individuals or groups approve or disapprove of performing a given behavior” (Aj zen, 1991 , 195). Finally, perceived behavioral control refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior in question as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles (Ajzen, 1991). Given that higher levels of financial literacy are l ikely to impact an individual’s perceived behavioral control, namely the perceived ease of securing financing and managing a business from the financial standpoint, we believe that financial literacy can shape entrepreneurial intentions. We discuss financial literacy next.

Financial Literacy

Financial literacy consists of an individual’s knowledge in managing economic information for decision making (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011). In the context of entrepreneurship, financial literacy consists of an individual’s “understanding of financial products, risks stemming from business initiatives as well as managing money and financial liabilities” (Trunk and Dermol, 2015, p. 2088). Individuals with higher levels of financial literacy were found to be better at paying credit cards and tracking bills (Hilgert et al., 2003), more effectively managing money (Klapper et al., 2014), and hedging risks by diversifying investment portfolios (Giuso & Jappelli, 2008). Financial literacy enables entrepreneurs to make effective decisions regarding the utilization of financial products and services (Wise, 2013) such as managing loans, savings, and investments (Brown & Graf, 2013; Rooij et al., 2011) and improves practices such as record keeping of business transations (Nama et al., 2023).

Using a Chinese data set on family economic activities, (Li & Quian, 2020) find that “with every unit increase in financial literacy, the probability of participating in entrepreneurship will increase by 1.9 percent” (Li & Quin, 2020). This suggests that a better understanding of topics like interest rates, time value of money, and investment risk are associated with a higher probability of entrepreneurial participation. Others (Yin et al., 2015; Cumurovic & Hyll, 2019) find that financial literacy and entrepreneurial entry are positively corelated. Lusardi (2009) shows that being financially informed could inspire people's financial decisions to establish a company. Financial literacy was indeed found to lead to higher interest in entrepreneurship (Aldi et al., 2018; Song et al., 2020), better ability to exploit opportunities (Glaser and Walther, 2013), higher likelihood to develop entrepreneurial intentions (Ahmad et al., 2019; Bilal et al., 2021; Suratno et al., 2021) and potential for success as an entrepreneur (Munyuki et al., 2022).

Because most entrepreneurial activities start with household assets as the initial investment (Dyer, 2003), lack of startup capital is a significant barrier to starting a new venture (Engelschion, 2014; Herrington & Kew, 2014; Li & Qian, 2020). Financial capital is regarded as a primary source required by new ventures (Brush et al., 2001). Lack of financial savvy can lead to higher borrowing costs and more debt, reducing the likelihood that an aspiring entrepreneur will be able to neither gather sufficient capital for startup nor manage it efficiently (Stago & Zinman, 2009). Indeed, (Pruett et al., 2008) identified lack of knowledge in management, accounting, and finance as significant barriers to entrepreneurship among university students in the U.S., China and Spain.

(Igbokwe, Gesinde & Adeoye, 2014) examine three different dimensions of financial literacy, what they label as financial intelligence: spending, saving, and giving. The ‘spending’ dimension consists of one’s awareness of financial resources available and spending within a budget. The ‘saving’ dimension assesses one’s awareness of controlling expenses, saving, and planning to save. The third dimension is labeled ‘giving,’ and encompasses financial resources that can be provided to others. This is especially relevant in the Iranian context, given the importance charity as a core Islamic value (Adas, 2006; Sloane White, 2011). Indeed, Adas (2006) who studied Muslim entrepreneurs in Turkey found that Muslim entrepreneurs integrate Islamic values in entrepreneurship. For example, Islam prohibits charging interest which means that many nascent entrepreneurs seek to borrow from friends and family (Adas, 2006). Based on (Igbokwe et al., 2014) identified dimensions of financial knowledge, we propose that:

H1: The spending dimension will have a significant effect on students' EI.

H2: The saving dimension will have a significant effect on students' EI.

H3: The money-giving dimension will have a significant effect on students' EI.

The Gender Gap

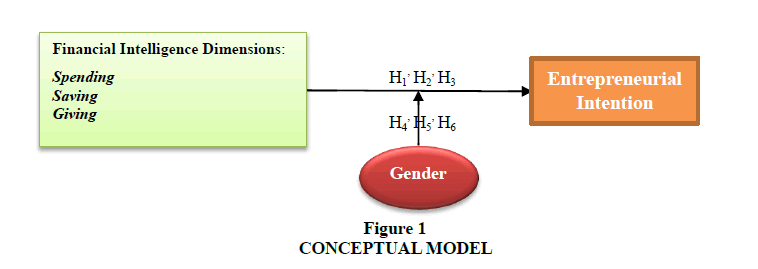

Given significant differences across genders in entrepreneurial intentions and activity (Elam et al., 2021; Jenning et al., 2022; Quigley & Patel, 2022), gender is often included as a moderating as well as a mediating variable in entrepreneurship studies (Sullivan & Meek, 2012). Furthermore, in the context of financial literacy, some studies identify gender differences in financial skills, such as saving, borrowing, trading, and risk management (Allen et al. 2016; Cull et al. 2007; Rojas Suarez, 2010) with women having lower financial literacy compared to men (Buvinic & Berger, 1990; Carter & Shaw, 2006; Kairiza et al., 2017). (Trunk & Dermol, 2015), in their study of university students in Slovenia, found that men were significantly more inclined to gather financial information compared to their female peers. Similarly, (Kairiza et al., 2017) find that female entrepreneurs take less initiative in exploiting available financial services and entering formal financial markets compared to their male counterparts. This is aligned with (Mandell’s, 2008) findings that male university students in the U.S., ranked higher on financial literacy compared to their female peers. Based on the gender differences identified in the literature, we hypothesize that in Figure 1:

H4: Gender moderates the effect of the spending dimension on students' EI.

H5: Gender moderates the effect of the saving dimension on students' EI.

H6: Gender moderates the effect of money-giving dimension on students' EI.

Sample

Mandell (2008) found that university students in business education and other quantitative fields like science and engineering, tend to rank higher on aspects of financial literacy like income management, saving, and spending. For this reason, this study surveyed accounting students in Iran. Because of limitations created by the COVID 19 pandemic, data collection was conducted via an online questionnaire, using the Aval Form software. All accounting students from all universities across Iran were invited to participate through different social networks such as Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram. This approach constitutes a simple random sampling approach, which resulted in 514 completed questionnaires. After discarding 10 questionnaires with incomplete responses, the final sample of 504 questionnaires was utilized for data analysis.

The use of student samples to examine entrepreneurial intentions has received some support because “students face an immediate career choice [and] …starting a business may be a realistic option for them” (Krueger et al., 2000, p. 425). Similarly, (Hmieleski & Corbett , 2006) , p. 59) advocate “the importance of studying the intentions of students, who, through university…programs and the increased infusion of entrepreneurship across educational curriculums, experience increasingly lower barriers in starting their own businesses.” In addition, student samples are very common in entrepreneurship research (Liñán & Chen, 2009), especially given evidence that 25 to 34 year old university graduates show the highest propensity toward starting up a firm (Reynolds et al., 2004).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire included items on respondents’ demographic characteristics as well as individual entrepreneurial intentions and financial knowledge. Entrepreneurial intention (EI) was measured using (Liñan & Chen’s, 2009) well established six item scale. The seven point Likert scale ranged from “1” being “completely disagreed” to “7” being “completely agree.” The items were: (1) “I am ready to do anything to become an entrepreneur;” (2) “My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur;” (3) “I will do whatever it takes to set up and run my own company;” (4) “I am determined to set up my own company in the future;” (5) “I have thought seriously about setting up a company;” and (6) “ I have the firm intention to set up my own company one day".

Igbokwe et al.’s (2014) 25 item financial knowledge scale was used to assess the three dimensions of saving, spending, and giving. The spending dimension included 11 items, such as: (1) “I always make a list of what I want to buy,” and “I understand I have limited resources.” The saving dimension included 9 items such as: (1) “I plan the amount to save every month,” (2) “I maintain a savings account,” and (3) “I systematically save for what I want to purchase.” The giving dimension included 5 items such as: (1) “I make an account of every amount of money I give,” and (2) I am aware of the need to give.” All items were rated on a five point Likert type scale ranging from “1” being “not at all” to “5” being “always.” Table 2 shows the scales’ convergent and diagnostic validity as well as the Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α) and composite reliability (CR) (See Table 2).

Analysis

Data analysis was completed using the SPSS (ver. 27.0) and SmartPLS (ver. 3.0) software packages. For this purpose, descriptive (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation (SD) and inferential (SEM, viz. measurement model evaluation and structural model evaluation as well as the partial least squares (PLS) regression) statistics were utilized. In the evaluation section of the measurement model, the validity, reliability, and fit of the latent variables were considered. In the evaluation section of the structural model, the hypotheses were tested in the form of the proposed research model. In addition, multigroup analysis (MGA) was used to investigate the moderating role of gender.

Findings

Descriptive Statistics

A total of 59.3% of the respondents were female and 40.7% were male. Mean age was 26.18 (SD of 6.82, ranging from 19 to 50). The age range among university students in Iran is significantly broader than in other nations given that many working adults seek to advance their educational attainement for career growth pruposes. The mean score for entrepreneurial intention was 3.12 (with a SD of 0.93), which is a moderate level. In terms of financial knowledge, the mean for the spending dimension was 3.62 (SD of 0.87), the mean for the saving dimension was 3.68 (SD of 0.89), and the mean for the money giving dimension was 4.01 (SD of 0.66). These results suggest an above average level of financial knowledge.

Model Fit

To check the fit, validity, and reliability of the measurement model of the latent variables, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed. The goodness of fit (GoF) indices (See Table 1), the summary of the results (See Table 2), and the correlation coefficients, and the root mean square (RMS) extraction (See Table 3) were all considered satisfactory. Results show that the indices of the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the normed fit index (NFI), and the root mean square residual covariance matrix of the outer model residuals (RMS theta) have good values; therefore, the fit of the measurement model of the latent variables in this study was established (See Table 1).

| Table 1 Gof Indices Of The Measurement Model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fitness index | SRMR | NFI | RMS_Theta |

| Suggested value | <0.10 | >0.80 | ≤0.12 |

| Estimated value | 0.077 | 0.94 | 0.11 |

Given that the CR value was equal to or greater than 0.7 and the average variance extracted (AVE) was equal to or greater than 0.50, reliability and convergent validity are established (Hair et al., 2017). The CR values and convergent validity (viz. AVE) for the measurement model of all the latent variables of the study are respectively greater than 0.82 and 0.53, so the measurement model of the latent variables of the research had acceptable reliability and convergent validity (See Table 2).

| Table 2 Results Of The Measurement Model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Variable | Mean (SD) | CR | AVE | α |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | 3.12 (0.93) | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.9 |

| Spending knowledge | 3.62 (0.87) | 0.87 | 0.63 | 0.83 |

| Saving knowledge | 3.68 (0.89) | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.85 |

| Giving knowledge | 4.01 (0.66) | 0.82 | 0.53 | 0.72 |

A square root of AVE for each construct greater than the estimated correlation coefficient between that construct and other constructs in the research model, confirms the discriminant validity of that variable (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Our results (See Table 3) show the square root AVE for each construct in the research model (0.73<AVE<0.84) is greater than the correlation coefficient (0.16<r<0.64) between the constructs of the research model. These demonstrate good discriminant validity for the measurement model of all the latent variables. A collinearity test was further used to check common method bias (CMB). Given that the VIF for each latent variable is less than 3.3 (See Table 3) we can determine that the model is free from CMB (Koch, 2015).

| Table 3 Root Mean Of The Extracted Variance And The Correlation Coefficients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | VIF |

| 1- Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.84 | - | |||

| 2- Spending knowledge | 0.22 | 0.8 | 1.96 | ||

| 3- Saving knowledge | 0.25 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 1.97 | |

| 4- Giving knowledge | 0.16 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.73 | 1.8 |

| Note: The numbers of the diagonal elements represent the root mean of the extracted variance and the lower elements show the correlation coefficients between the constructs. | |||||

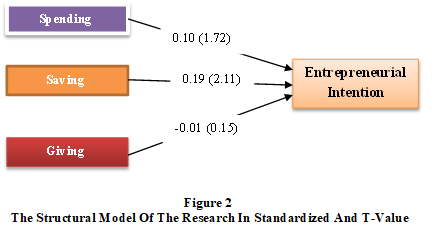

Upon verifying the measurement model of the latent research variables using CFA, the path analysis method (i.e., structural model evaluation) was used to test the hypotheses in the form of the proposed research model. The research path model was then presented by the standardized path coefficient and significance level (See Figure 2) along with the summary of the results for the structural model evaluation (See Table 4).

Results

Findings (See Table 4) show that the direct path coefficient of the latent variable of the spending dimension on EI is not statistically significant (beta=0.10, t=1.07), failing to support Hypothesis 1. The latent variable of the saving dimension, on the other hand, shows a significant positive effect on EI at the 5% error level (beta=0.198, t=2.11), supporting hypothesis 2. Finally, findings show that the effect of the latent variable of the money giving dimension on students' EI was not statistically significant ( 0.01, t=0.14) failing to support hypothesis 3.

| Table 4 Structural Model Evaluation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Variable | Path Coefficients | Conclusion | |||

| Dependent | Independent | β | t | R2 | |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | Spending knowledge | 0.1 | 1.07 | Reject H1 | 0.07 |

| Saving knowledge | 0.198 | 2.11* | Accept H2 | ||

| Giving knowledge | -0.013 | 0.14 | Reject H3 | ||

| Significant at the 5% error level | |||||

Gender Moderating Effects

The MGA was used to investigate the moderating role of gender in the relationship between the financial knowledge dimensions and entrepreneurial intentions (See Table 5). The spending and saving dimensions both show a significant positive effect on EI among the female students but not so for the money giving dimension. Meanwhile, among the male students, only the saving dimension had a significant positive effect on EI. These results show that gender moderates the effect of the spending dimension on EI among Iranian accounting students. Namely, the impact of the spending dimension on EI was greater in female students than for the male students. The MGA results did not validate the moderating role of gender in the relationship between the saving dimension and EI. Therefore, the fourth and sixth research hypotheses were confirmed, and the fifth research hypothesis was rejected.

| Table 5 Moderating Role Of Gender |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Path | Path coefficient(t-value) | Path coefficient difference | t-value | Significance level | |

| Female | Male | ||||

| Spending knowledge → EI | 0.31 (2.95**) | -0.16 (0.99) | 0.47 | 2.63** | 0.011 |

| Saving knowledge →EI | 0.26 (2.17*) | 0.31 (2.44*) | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.79 |

| Giving knowledge → EI | -0.25 (1.81) | 0.20 (1.50) | 0.45 | 2.19* | 0.029 |

| Significant at the 1% error level and *Significant at the 5% error level | |||||

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the saving dimension had a significant and positive effect on EI among accounting students regardless of gender. Considering that any entrepreneurial activity involving the creation of a new business (small, medium, or large) requires capital, this finding is not surprising. Individuals, who understand ways to save for the future and manage investments, are thus more likely to have startup capital which can impact their intentions to start a business. These findings are consistent with past research (Kamil et al., 2014; Ronald & Grable, 2010; Shi, 2012; Suratno et al., 2021). However, contrary to past research (Kamil et al., 2014; Suratno et al., 2021;), our results did not show a significant effect on EI for the spending or money giving dimensions. It is possible that students who intend to start businesses in the future are more likely to look for saving opportunities rather than focus on spending or giving money to others.

Additional insights are revealed from our examination of the moderating role of gender on the relationship between the different financial knowledge dimensions and EI. In keeping with previous research (Allen et al., 2016; Cull et al., 2007), this study’s results show gender differences in the impact of financial knowledge. First, the spending dimension had a significant and positive effect on EI among female respondents but not among male respondents. It is possible that because women are often responsible for household expenses and budgeting, this dimension matters more to them. Meanwhile, the saving dimension had an impact on EI for all respondents, regardless of gender. Finally, we did not find the giving dimension to impact entrepreneurial intentions. It is possible that university graduates, who are not yet established in their careers, are less focused on giving, and more on saving and spending. In general, these findings point out the varying effect of gender in the impact financial knowledge can have on EI and related actions. This can be informative for policy makers focused on entrepreneurship development. We discuss some of these implications next.

Limitations and Areas for Future Research

There are a number of limitations to our study, several of which present promising directions for future research. First, our study examined entrepreneurial intentions among university students in only one national context (Iran). Future research could investigate the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial intentions as well as the impact of gender on this link in other national contexts. Another limitation is our sample’s lack of variation in the field of education. All of our respondents were accounting students who, as the nature of their course work, are likely to have higher levels of financial literacy. A sample with variance in educational fields might have greater variance in EI, especially in disciplines outside business or other quantitative fields like science and engineering. Finally, while there is some support for the notion that intentions lead to actual behavior (Díaz & Jiménez, 2010; Liñan, 2008; Liñan Chen, 2009; Liñan et al. 2010; Moriano et al. 2011) longitudinal work measuring actual entrepreneurial behavior among university graduates would be invaluable. Future research could assess whether students who had access to financial literacy education actually start businesses at higher numbers.

Implications and Recommendations

Our results have several theoretical and practical implications. In terms of the theoretical implications, our findings show that financial knowledge can impact EI as well as the fact that gender matters in this relationship. Future studies examining antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions, should consider financial literacy. In addition, it is important for researchers to acknowledge that financial knowledge and implications thereof may differ between men and women.

In terms of the practical implications for policymakers, public officials, and planners in higher education, our findings suggest that financial literacy can impact entrepreneurship development among students and graduates and thus reduce unemployment. This is especially true regarding knowledge around saving. Investing in financial literacy education can potentially serve to increase entrepreneurial intentions among university graduates in Iran. This might be especially important for individuals who are hesitant to start their own business due to lack of understanding about financial management. Educational institutions like universities are well situated to offer educational programs to current students as well as working adults on basic financial concepts like budgeting, cash flow management, and investment strategies. This can be offered through continuing education workshops or online courses. Such educational opportunities may boost individuals’ confidence in their ability to make well informed financial decisions and as a result, be more likely to start their own business. Nascent entrepreneurs could equally benefit from access to financial advisors, mentors, and peer networks to further develop their financial literacy.

To address the gender gap and increase entrepreneurial intentions among women, providing access to education on funding sources, specifically for nascent female entrepreneurs could be valuable. Indeed, existing research identified some of the social benefits resulting from female entrepreneurship in terms of job creation and wages (Sanchez Riofrio et al., 2023). Expanding mentorship opportunities for aspiring female entrepreneurs as a way to boost financial literacy could thus be beneficial. To enhance financial literacy among women, universities can offer workshops, coursework or continuing education programs on business financial management targeting women.

References

Adas, E.B. (2006), “The making of entrepreneurial Islam and the Islamic spirit of capitalism”, Journal for Cultural Research, Vol.10 No. 2, pp. 113-137.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ahamad, N. and Seymour, R.G. (2008), “Defining entrepreneurial activity: Definitions supporting framework for data collection”, OECD Statistics Working Papers 2008/1. OECD Publishing.

Ahmad, N.L., Yusof, R., Ahmad, A.S. and Ismail, R. (2019), “The importance of financial literacy towards entrepreneurship intention among university students”, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 9, pp. 18-39.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ajzen, I. (1991), “The theory of planned behavior”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, Vol. 50, pp. 179-211.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Aldi, B.E., Herdjiono, I., Maulany, G. and Fitriani, B. (2018), “The influence of financial literacy on entrepreneurial intention”, Proceedings of the 3rd annual Conference on Accounting, Management and Economics.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., and Martinez-Peria, M. S. (2016), “The foundations of financial inclusion: understanding ownership and use of formal accounts”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 27, pp. 1–30.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alshebami, A.S. and Al Marri, S.H. (2022), “The impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of saving behavior”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 13, pp. 1-10

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baughn, C.C., Cao, J.R., Le, L.T.M., Lim, V.A. and Neupert, K.E. (2006), “Normative, social and cognitive predictors of entrepreneurial interest in China, Vietnam, and the Philippines”, Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 57-77.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bilal, M.A., Khan, H.H., Irfan, M., Ui Haq, S.M.N., Ali, M., Kakar, A., Ahmed, W. and Rauf, A. (2021), “Influence of financial literacy and education skills on entrepreneurial intent: Empirical evidence from you entrepreneurs in Pakistan”, Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 697-710.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bird, B. (1988), “Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: the case for intentions”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 13, pp. 442-454.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Boubker, O., Arroud, M., and Ouajdouni, A. (2021), “Entrepreneurship education versus management students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A PLS-SEM approach”, The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Vol. 19 No. 1, p. 100450.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brown, M. and Graf, R. (2013), “Financial literacy, household investment and household debt: Evidence from Switzerland. Working Paper on Finance, No. 13/1. Swiss Institute of Banking and Finance.

Brush, C., Greene, P., Hart, M. and Haller, H. (2001), “From initial idea to unique advantage: The entrepreneurial challenge of constructing a resource base”, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 64-78.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bullough, A., Renko, M., and Myatt, T. (2014), “Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 38, pp. 473-499.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Buvinic, M., and Berger, M. (1990), “Sex differences in access to a small enterprise development fund in Peru”, World Development, Vol. 18 No. 5, pp. 695–705.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carter, S., and Shaw, E. (2006), Women’s business ownership: recent research and policy development. London: DTI Small Business Service Research Project.

Cheng, C.T., Tang, Y., and Buck, T. (2021), “The interactive effective of cultural values and government regulations on firms’ entrepreneurial orientation”, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Development, Vol. 29, pp. 221-240.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cull, R., Demirgüc-Kunt, A., and Morduch, J. (2007), “Financial performance and outreach: A global analysis of leading microbanks”, Economic Journal, Vol. 117, pp. 107–133.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cumurovic, A. and Hyll, W. (2019), “Financial literacy and self-employment”, The Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 53 No. 2, pp. 455-487.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Davidsson, P. (1995), “Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions”, Paper presented at the RENT LX Workshop, Nov. 23-24, Piacenza, Italy.

de Bruin, A., Brush, C.G., and Welter, F. (2007), “Advancing a framework for coherent research on women’s entrepreneurship”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 323-339.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Díaz-García, M. and Jiménez-Moreno, J. (2010), “Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of gender”, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal,Vol. 6, pp. 261-283.

Dyer, W.G. (2003), “The family: The missing variable in organizational research”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 27 No. 4, pp. 401-416.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Engelschion, A.S. (2014), “Does increased access to financial enhance entrepreneurial activity among students? How perceived access to finance affects entrepreneurial intentions”, Theses. University of Stravaner, Norway.

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Glaser, M. and Walther, T. (2013), “Run, walk or buy? Financial literacy, dual-process theory, and investment behavior”, Technical Report, LMU, Munich. Giuso, L. and Jappelli, T. (2008), “Financial literacy and portfolio diversification”, Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance, Working paper No. 212.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hasan, M., Musa, C.I., Tahir, T., Azis, M., Rijal, S. and Ahmad, M.I.S. (2020), “How does entrepreneurial literacy and financial literacy influence entrepreneurial intention in perspective economic education?”, Talent Development and Excellence, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. 5569-5575.

Herrington, M. and Kew, J. (2014), “Global entrepreneurship monitor: South African report. Twenty years democracy, Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship”, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

Hilgert, M.A., Hogarth, J.M., and Beverly, S.G. (2003), “Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior”, Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 89 No. 7, pp. 309-322.

Hmieleski, K. M. and Corbett, A. C. (2006), “Proclivity for improvisation as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions”, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 44 No. 1, pp. 45-63.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hussaina, M.D., Bhuiyanb, A.B. Said, J., and Halim, M.S. (2017), “Entrepreneurship education is the key contrivance of poverty alleviation: An empirical review”, Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 1, pp. 32-41.

Igbokwe, D.O., Gesinde. A.M., and Adeoye. T. A. (2014), “Development and validation of indices of financial intelligence among a cross-section of Nigerian private university students”, International Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 76-81.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jiatong, W., Murad, M., Bajun, F., Tufail, M.S., Mirza, F. and Rafiq, M. (2021), “Impact of entrepreneurship education, mindset, and creativity on entrepreneurial intentions: Mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy”, Frontiers in Psychology.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kairiza, T., Kiprono, P., and Magadzire, V. (2017), “Gender differences in financial inclusion amongst entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe”, Small Business Economics, Vol. 48 No. 1, pp. 259-272.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kamil, N.S.S.N., Musa, R., and Sahak, S. Z. (2014), “Examining the role of financial intelligence quotient (FiQ) in explaining credit card usage behavior: A conceptual framework”, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 130, pp. 568-576.

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A. and Van Oudeusen, P. (2014), “Financial literacy around the world: Insights from the standard & Poor’s rating services global financial literacy surveys”.

Koch, N. (2015), “Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach”, International Journal of e-Collaboration, Vol. 11 No. 4, pp. 1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kolvereid, L. (1996), “Prediction of employment status choice intentions”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 47-61.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kolvereid, L. and Moen, O. (1997), “Entrepreneurship among business graduates: Does a major in entrepreneurship make a difference?” Journal of European Industrial Training, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 154-160.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., and Carsrud, A.L. (2002), “Competing models of entrepreneurial Intentions”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 15 No. 5-6, pp. 411-432.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, R. & Qian, Y. (2020), “Entrepreneurial participation and performance: The role of financial literacy”, Management Decision, Vol. 58 No. 3, pp. 583-599.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Liñan, F. (2008), “Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions?” International Entrepreneurship Management Journal, Vol. 4, pp. 257-272.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Liñan, F. and Chen, Y.W. (2009), “Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 33 No. 3, pp. 593-617.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Liñan, F., Rodrigues-Cohard, J. and Rueda-Cantuche, J. (2011), “Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education”, The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 195-218.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Liñan, F., Roomi, M.A. and Santos, F. (2010), “A cognitive attempt to understanding female entrepreneurial potential: The role of social norms and culture”.

Lusardi, A. (2009), “U.S. Household Savings Behavior: the role of financial literacy, information and financial education programs”, in C. Foote, L Goette, and S. Meier (eds.), Policymaking Insights from Behavioral Economics. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, pp. 109-149.

Lusardi, A. and Mitchell, O.S. (2011), “Financial literacy around the world: An overview”, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 497-508.

Mandell, L. (2008), “The financial literacy of young American adults. Results of the 2008 national Jump$tart coalition survey if high school seniors and college students”.

Mbhele, T.P. and Qhwagi, L.I. (2023), “Propernsity to engage in youth entrepreneurship in the face of Covid-19: The case of Klaarwater township”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 1-17.

Mirzasafi, A., Rajaeepour, S., and Jamshidian, A.R. (2011), “The Relationship between information literacy and entrepreneurial capabilities of graduate students of Isfahan University”, Library and Information Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 241-268.

Moriano, J.A., Gorgievski, M., Laguna, M., Stephan, U. and Zarafshani, K. (2011), “A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intentions”, Journal of Career Development, Vol. 38 No. 1, pp. 1-24.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Munyuki, T. and Coretta M.P.J. (2022), “The nexus between financial literacy and entrepreneurial success among young entrepreneurs from a low-income community in Cape Town: A mixed-methods anbalysis”, Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 137-157.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Murad, M., Li, C., Ashraf, S.F. and Arora, S. (2021), “The influence of entrepreneurial passion in the relationship between creativity and entrepreneurial intention”, International Global Business Competitiveness, Vol. 16, pp. 51-60.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nama, S., Kamga, B.F. and Beninguis, G. (2023), “Impact of training in management and agricultural techniques in Cameron: Evalutioant of the ‘Manage Your Business Better’ training tool”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Vol. 2, No. S2, pp. 1-14.

Pruett, M., Shinnar, R.S., Toney, B., Llopis, F. and Fox, J. (2008), “Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study”, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, Vol. 15 No. 6, pp. 571-594.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Quigley, N.R., and Patel, P.C. (2022), “Reexamining the gender gap in microlending funding decisions: The role of borrower culture”, Small Business Economics.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reynolds, P. D., Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B. and Greene, P. G. (2004), “The prevalence of nascent entrepreneurs in the United States: Evidence from the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics”, Small Business Economics Vol. 23 No. 4, pp. 263-284.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rikwentische, R., Musa Pulka, B., and Msheliza, S.K. (2015), “The effects of saving and saving habits on entrepreneurship development”, European Journal of Business Management, Vol. 7, pp. 111-119.

Rojas-Suarez, L. (2010), “Access to financial services in emerging powers: facts, obstacles and policy implications”, OECD Development Centre Publishing, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2559807 (accessed May 29, 2023)

Ronald, S., and Grable, J. (2010), “Financial numeracy, net worth, and financial management skills: client characteristics that differ based on financial risk tolerance”, Journal of Financial Service Professionals, Vol. 64 No. 6, pp. 57-63.

Rooij, V.M.C., Lusardi, A. and Alessie, R.J. (2011), “Financial literacy and retirement planning in the Netherlands”, Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 32 No. 4, pp. 593-608.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sabri, M. and MacDonald, M. (2010), Savings behavior and financial problems among college students: The role of financial literacy in Malaysia”, Crosscultural Communication, Vol. 6, pp. 103-110.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sanchez-Riofrio, A.M., Lupton, N.C., Camino-Mogro, S., and Acosta-Avila, A. (2023), “Gender-based characteristics of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in an emerging country: Is this a man’s world?” Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 652-673.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shafinar, I., Arnida, J., Nadiah, M.S.A., Rozana, O., Naina, M.R., Syazwani, K.N. (2015), “Determinants of savings behavior among Muslims in Malaysia: An empirical investigation”, In Omar, R., Bahrom, H., and de Mello, G. (Eds.). Islamic Perspectives Relating to Business, Arts, Culture and Communication. Springer, Singapore.

Shi, Q. (2012), “China women entrepreneurship: A survey”, Presentation at the ADB-OECD joint workshop on gender differences in education, employment, and entrepreneurship in India, Indonesia, and PRC, Manila. February.

Shinnar R.S., Giacomin, O. and Janssen, F. (2012), “Entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions: The role of gender and culture”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 435-493.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shiri, N., Mirakzadeh, A., and Zarafshani, K. (2017), “Promoting entrepreneurial behavior among agricultural students: a two-step approach to structural equation modeling”, International Journal of Agricultural Management and Development, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 211-221.

Shiri, N., Moradnezhadi, H., Mahdizadeh, H., and Seymohammadi, S. (2021), “Opportunities for Student Cooperatives Startup at Ilam University: Guidelines for the Development of Agricultural and Service Cooperatives”, Co-Operation and Agriculture, Vol. 10 No. 39, pp. 103-121.

Shiri, N., Shinnar, R.S., Mirakzadeh, A.A. and Zarafshani, K. (2017), “Cultural values and entrepreneurial intentions among agriculture students in Iran”, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Vol. 13, pp. 1157-1179.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shukla, S., Dwivedi, A.K. and Acharya S.R. (2022), “Entrepreneurship teaching in India and the region”, Journal of Entrepreneurship, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 160-184.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sloane-White, P. (2011), “Working in the Islamic economy: Sharia-ization and the Malaysian Workplace”, Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, Vol.26 No. 2, pp. 304-334.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Song, Z., Mellon, G. and Shen, Z. (2020), “Relationship between racial bias exposure,financial literacy, and entrepreneurial intention: An empirical investigation”, Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Management

Stago, V. and Zinman, J. (2009), “Exponential growth bias and household finance”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 64 No. 6, pp. 2807-2849.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sullivan, D.M. and Meek, W.R. (2012), “Gender and entrepreneurship: a review and process model”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 27 No. 5, pp. 428-458.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Suratno, S., Narmaditya, B., and Wibowo, A. (2021), “Family economic education, peer groups and students’ entrepreneurial intention: the mediating role of economic literacy”, Heliyon.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

The World Bank (2016), “Financial education in the Arab world: Strategies, implementation and impact”.

Thurik, A.R., Carree, M.A., Van Stel, A. and Audretsch, D.B. (2008), “Does self-employment reduce unemployment?”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 23 No. 6, pp. 673-686.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Trunk, A. and Dermol, V. (2015), “EU integration through financial literacy and Entrepreneurship”, Management Knowledge and Learning Conference Proceedings, Bari, Italy.

van Gelderen, M., Brand, M., van Praag, M., Bodewes, W., Poutsma, E. and van Gils, A. (2008), “Explaining entrepreneurial intentions by means of the theory of planned behavior”, Career Development International, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 538-559.

Wise, S. (2013), “The impact of financial literacy on new venture survival”, International Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 8, pp. 30-39

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 30-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-23-13763; Editor assigned: 03-Jul-2023, Pre QC No. IJE-23-13763(PQ); Reviewed: 17-Jul-2023, QC No. IJE-23-13763; Revised: 20-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-23-13763(R); Published: 27-Jul-2023