Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Fear of Isolation on Social Networking Sites Regarding State Institutions in Pakistan: Attitude Strength as a Mediating Variable

Asif Arshad, University of Okara

Farahat Ali, University of Central Punjab

Muhammad Ans, University of Central Punjab

Muhammad Awais, University of Management and Technology

Andleeb Ikhlaq, University of Central Punjab

Citation Information: Arshad, A., Ali, F., Ans, M., Awais, M., & Ikhlaq, A. (2023). Fear of Isolation on Social Networking Sites Regarding State Institutions in Pakistan: Attitude Strength as a Mediating Variable. Journal of Organizational Culture Communications and Conflict, 27(2), 1-14.

Abstract

Adopting the spiral of silence framework, this study examines the association between fear of isolation on social networking sites and willingness to self-censorship. Moreover, this study investigates the mediating role of attitude strength in the relationship between contextual fear of isolation and social media users’ willingness to self-censorship. Based on a cross-sectional survey design, this study collected data through a self-administered questionnaire from 600 university students. Findings through structural equation modeling showed that dispositional fear of isolation and contextual fear of isolation regarding judiciary lead social media users towards willingness to self-censorship. A significant relationship was also observed between contextual fear of isolation and attitude strength. Attitude strength significantly predicted willingness to self-censorship in all institutions except the army. Locale and ethnicity were significant predictors of the willingness to self-censorship. The findings further revealed that attitude strength towards judiciary and religion significantly mediates between contextual fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship.

Keywords

Fear of Isolation, Willingness to Self-censorship, Spiral of Silence, Social Networking Sites, Attitude Strength, Religious Extremism, State Institutions.

Introduction

On January 4, 2017, Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) Cyber Crime Wing detained five bloggers for allegedly posting blasphemous content on Facebook. In reality, the missing bloggers were human rights activists who openly criticized religious extremism and powerful military establishment on social media. After their illegal detention, extremist elements launched a virulent social media campaign and demanded their execution. Later investigations proved that these bloggers were not involved in disseminating blasphemous content (Imran, 2017). To be certain, this incident created an atmosphere of fear and discouraged enlightened voices on social media.

Over the past decade, several incidents of enforced disappearance have taken place in Pakistan. Recently, prominent journalists and human rights activists were investigated because they protested upon the arrival of Saudi crown prince Mohammad Bin Salman by displaying pictures of Jamal Khashoggi on their social media profiles (Farmer, 2019). In the past year, FIA arrested journalist Rizwanur Rehman Razi for posting derogatory remarks against the military establishment on Twitter (Shahzad, 2019). In June 2018, a female journalist Gul Bukhari, a vocal critic of the Pakistan army on social media, was abducted in Lahore by an intelligence agency (Zulqernain, 2018).

According to Amnesty International, freedom of expression is being curbed in Pakistan by threatening social media users. Social media activists are soft targets who face harassment and threats of violence. How can we forget the lynching of Mashal Khan? In April 2017, a Pashtun student Mashal Khan was brutally killed inside Abdul Wali Khan University by an angry mob on false allegations of spreading blasphemous content on Facebook. Similarly, a crowd of 500 people attacked at the police station to lynch a Hindu person Prakash Kumar who reportedly posted an offensive image on social media (Guardian, 2017). The abovementioned incidents unveil the seriousness of the situation.

It is an undeniable fact that people who think critically, raise questions, challenge facts, and dislike the status quo suffer a lot. They have to face hostility from a loud majority. Oftentimes, their opinion is suppressed. This grave situation leads them towards fear of isolation (Neumann, 1974). It has been observed that social media activists are facing serious issues around the world. In Pakistan, they have to face adverse circumstances in case of taking a hard line contrary to state policies. A time comes when state institutions consider them a security threat and they are illegally detained under controversial cyber-crime laws. When social media users give their opinion on a controversial religious issue, religious elements issue verdicts of blasphemy against them and call them infidels. Subsequently, social media users impose selfcensorship upon them while posting something on sensitive issues.

This study aims to explore the relationship between dispositional/contextual fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship. Furthermore, this study investigates the mediating role of attitude strength in the relationship between contextual fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship. The extant literature on the spiral of silence framework showed a strong relationship between fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship (Chan, 2021; Chen, 2018; Fox & Holt, 2018; Matthes et al., 2012). Several studies have tested the spiral of silence theory in online context (Fox & Holt, 2018; Hampton et al., 2014; Ho & McLeod, 2008; Lee & Kim, 2014; Yun & Park, 2011). However, a little is known about the mediating role of attitude strength. This study bridges this gap exploring the mediating role of attitude strength in the relationship between contextual fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship. In short, this study tests the spiral of silence phenomenon in the context of new media with special reference to Pakistan.

Literature Review

After reviewing previous scholarly studies, researchers have come to know that a lot of studies have been conducted on this specific topic. In this portion, a critical review of previous scholarly work is presented. At the end of the literature, the research gap will be identified.

Noelle‐Neumann (1974) asserted that minority opinion holders fall prey to fear of isolation due to the dominancy of the majority. As a result, they refrain from expressing their views. Hayes et al. (2005) argued that willingness to self-censorship had a great influence on opinion expression. This trait-based characteristic varies from one individual to another. Before voicing opinion publicly, most of the people relied on information derived from the social environment. Hayes et al. (2011) observed that fear of social isolation leads people to get more information about the social environment. They observed the social environment before commenting on a controversial topic.

Erichsen & Bolliger (2011) tested the tenets of the spiral of silence theory among 64 international students. The results revealed that international students who were in the minority had a high level of fear of isolation. Likewise, the study of Lee et al. (2014) clearly showed that fear of isolation was one of the major factors that curbed free speech about controversial issues. Individuals who felt less fear were more likely to express their views. Lang (2014) also observed the same results in his study. Those who experienced less fear were more likely to express their views on social media. There was a significant difference in willingness to express views between members with a low and high level of attitude certainty. People felt more fear of being isolated in personnel communication. A Pew Research Center report based on the analysis of Hampton et al. (2014) identified the spiral of silence on social media regarding Edward Snowden’s 2013 leaks. The majority of respondents were less willing to express their views on this specific issue on SNS. Only 42% of Facebook and Twitter users were willing to express their views on this specific issue.

Ho and McLeod (2008) tested the spiral of silence phenomena in both offline and online contexts. The results indicated that respondents were more willing to express their views on controversial issues in online stetting. The study of McDevitt et al. (2003) resulted that participants didn’t reveal their real views in online chat room discussions on the issue of abortion. Yun & Park (2011) in their study found that respondents were more comfortable expressing their views in a friendly environment as compared to hostile conditions. Croucher et al. (2014) analyzed the spiral of silence phenomena in the US presidential election of 2008 among 569 respondents selected through convenience sampling technique. In this study, religion and religiosity were found to have a great influence on the willingness to express views. Those who were more inclined towards religion were more interested in discussing ethnicity as a voting issue.

Fox & Holt (2018) examined fear of isolation on social media concerning police discrimination among a sample of 399 respondents. The results demonstrated that dispositional and contextual fear of isolation regarding police lead towards self-censorship. However, there was a negative relationship between attitude strength towards police and self-censorship. Similarly, Chen (2018) analyzed the spiral of silence phenomenon in the context of new media. This study collected online data in two waves. The results showed a positive association between trait fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship. Moreover, the willingness to selfcensorship was found to be negatively associated with expressing views. Kushin et al. (2019) in their study found a negative relationship between fear of isolation and willingness to express views. Like most of the previous studies, Matthes et al. (2012) also observed a strong relationship between fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship. Chan (2021) also found the same results in his study. This study not only identified a positive association between fear of social isolation and willingness to self-censorship but also found the mediating effects of willingness to self-censor between fear of social isolation and express support for the party candidate.

Lee & Kim (2014) examined journalists’ willingness to express views on Twitter. The results showed that journalists who felt the difference in their opinion in both offline and online settings on controversial issues were less willing to express their views on Twitter. Conservative journalists were less willing to discuss controversial issues. The study of Neuwirth (2000) also showed that neutral respondents, who didn’t have a definite opinion, were not willing to express their views. Moreover, respondents who had views consistent with the majority were more willing to participate in political debate. Gearhart & Zhang (2014) found a negative relationship between willingness to self-censorship and opinion expression. People who were more willing to self-censor their views less commented on Facebook. The overall results demonstrated that the spiral of silence theory is still valid in the context of new media. Baldassare & Katz (1996) analyzed the impacts of attitude strength on willingness to express one’s opinion publicly. The results demonstrated that attitude strength plays a crucial role in predicting willingness to discuss opinions. People who had a great interest in politics were more willing to express their views publicly. The results further revealed that attitude strength is a dominant agent for breaking the spiral of silence.

Empirical literature showed that minority opinion holders have a high level of fear of isolation (Erichsen & Bolliger, 2011; Noelle‐Neumann, 1974; Yun & Park, 2011). Fear of social isolation leads towards willingness to self-censorship (Chan, 2021; Chen, 2018; Fox & Holt, 2018; Hayes et al., 2012). We know very little about the indirect effects of attitude strength between fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship.

Spiral of Silence

The theoretical framework of this study is based on the spiral of silence theory which was developed by a German political scientist Elizabeth Noelle-Neuman in 1974. This theory reflects a powerful effect model of the media and focuses on societal-level consequences. This theory states the reasons for disguising opinion, preference, and views of those who fall in minority groups. According to McQuail (2010), people try to hide their opinion if they feel they are in a minority and are more willing to express if they realize they are dominant. Subsequently, the dominant point of view gains more space and an alternative point of view become weaker. People’s fear of separation is the main cause of concealing views. They try to hide their true opinion in case of falling into a minority group (Baran & Davis, 2012).

According to the tenets of this theory, people fear to express their views on a controversial issue. Fear of isolation, fear of reprisal, and fear of segregation are major hurdles in the expression of views that force the public to observe the social environment before expressing views. The notion of fear of isolation was introduced by Elizabeth Noelle-Neuman in her book “The spiral of silence” in 1984. She wrote that we feel fear of being isolated because it is in human instinct to get respect and appreciation from other human beings. Now the question is when does spiral effect occur? A spiral effect occurs when minority opinion holders remain silent in front of a dominant majority opinion. The silence of the minority makes the majority opinion more powerful. Ultimately, the minority fall prey to fear of social isolation (Rosenberry & Vicker, 2017). Willingness to self-censor is an important factor of this theory that simply means to suppress a true opinion due to the disagreement of the audience (Hayes, 2005).

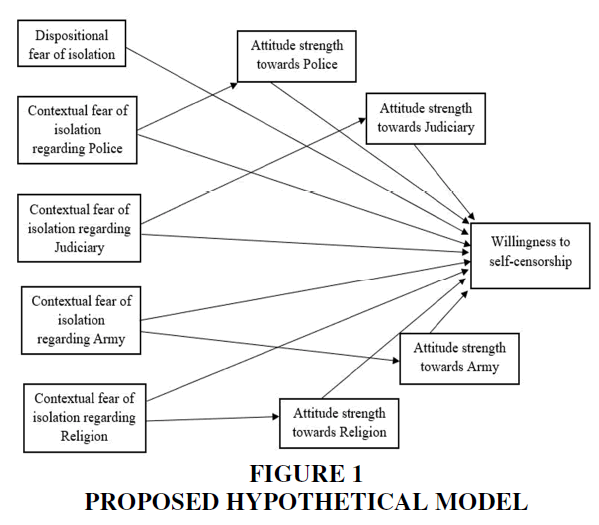

In many ways, the spiral of silence theory is in line with the present study. Social media users avoid writing critical posts due to the fear of the dominant majority and powerful state institutions, especially in third world countries. They can’t freely express their views about political and religious issues. They can neither challenge the dominance of the political elite nor promote moderate teachings of religion. In the case of sensitive and controversial issues, they fear to express their views. Minority opinion holders don’t express their views publicly due to the fear of the loud majority. As a result, the mainstream media don’t report minority opinions (Rosenberry & Vicker, 2017). Expressing views spontaneously may cause of fear of isolation. Fear of isolation is the main reason that affects the willingness to speak publicly on a controversial topic (McQuail, 2010). That’s why social media users who have minority opinions prefer silence over expression. The ultimate result of fear of isolation is that it leads users towards willingness to self-censorship. It is important to mention here that spiral of silence phenomenon mostly occurs when the topic of conversation is controversial (Neumann, 1993). In Pakistan, powerful establishment and religious elements are sacred cows. Researchers will find out whether social media users have a fear of isolation while commenting on state institutions and religious issues or freely express their views. If they feel fear, does this fear lead them towards willingness to self-censorship? Figure 1.

Hypotheses

H1: Dispositional fears of isolation lead social media users towards willingness to selfcensorship.

H2: Contextual fear of isolation regarding police on social networking sites lead social media users towards willingness to self-censorship.

H3: Contextual fear of isolation regarding the judiciary on social networking sites lead social media users towards willingness to self-censorship.

H4: Contextual fear of isolation regarding the army on social networking sites lead social media users towards willingness to self-censorship.

H5: Contextual fear of isolation regarding religion on social networking sites lead social media users towards willingness to self-censorship.

H6: Attitude strength towards police mediates between the relationship of contextual fear of isolation regarding police and willingness to self-censorship.

H7: Attitude strength towards judiciary mediates between the relationship of contextual fear of isolation regarding judiciary and willingness to self-censorship.

H8: Attitude strength towards army mediates between the relationship of contextual fear of isolation regarding army and willingness to self-censorship.

H9: Attitude strength towards religion mediates between the relationship of contextual fear of isolation regarding religion and willingness to self-censorship.

Method

Participants and Procedure

By employing a cross-sectional survey design, this study collected data through a selfadministered questionnaire from 600 university students from various public and private higher education institutes of Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan with the help of the convenience sampling technique. The questionnaire contained 61 close-ended items that covered all possible dimensions of the research topic. Overall, participants took 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Measures

Demographics

This study measured the demographic characteristics of respondents such as gender, locality, age, ethnicity, sect, qualification, and institution.

Social networking sites usage

Respondents were asked how much time they had spent on Facebook and Twitter regularly and weekends. The response options include a minimum of 30 minutes and a maximum of 240 minutes.

Fear of isolation

This study measured dispositional and contextual fear of isolation by adopting a scale from the study of Hayes et al. (2011). Dispositional (Trait) fear of isolation scale included five items such as “It is scary to think about not being invited to social gatherings by people I know.” Apart from measuring dispositional fear of isolation, this study also measured contextual fear of isolation regarding police, judiciary, army, and religion. Each sub-scale contained four items such as “I worry about being isolated if people disagree with me if I express my opinion about Police misconduct on Facebook/Twitter”, “I am afraid that others will judge me if I express my opinion about the wrong decisions of Judges on Facebook/Twitter”, “I feel I will lose friends or hurt relationships if I express my opinion about army’s role in politics and their intervention in government policies on Facebook/Twitter” and “I feel I will lose friends or hurt relationships if I express my opinion about religious institutions role in spreading extremism in the country on Facebook/Twitter.”

Attitude strength

Attitude strength towards police, judiciary, army, and religion was measured by adapting a scale developed by Fox and Holt (2018). Each sub-scale included 7 items such as “If a rich person and a poor person were under consideration for the same crime, the cops would be more likely to suspect the poor person”, “Judges who give verdict contrary to law should be charged with the same crime”, “The military relies on reports of intelligence agencies when they have to take action against militants” and “Religious scholars/institutions are more likely to discriminate if the suspect does not belong to their religion.”

Willingness to self-censorship

Willingness to self-censor scale was adapted from the study of Hayes, Glynn, and Shanahan (2005). It included eight items such as “It is difficult for me to express my opinion on Facebook/Twitter if I think others won’t agree with what I say” and “I’d feel uncomfortable if someone asked my opinion on Facebook/Twitter and I knew that he or she wouldn’t agree with me.” The responses of the above all constructs were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 2=Disagree; 3=Never; 4=Agree; 5=Strongly Agree).

Data Analysis

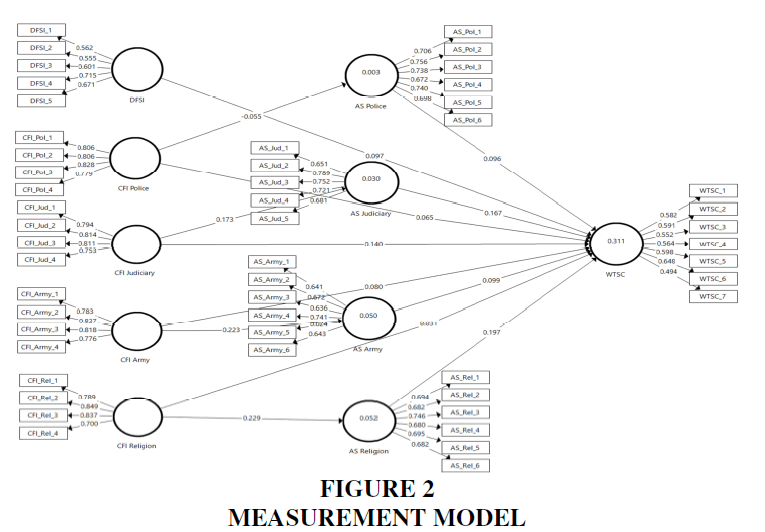

Partial least squares (PLS) based structural equation modeling (SEM) technique was used to empirically test the proposed hypothetical model. This study used a two-stage approach to assess PLS-SEM results: measurement model and structural model. Through PLS-SEM, we can test complex model that carries multiple predictors and outcome variables and above all, it works very well with smaller sample size (Hair et al., 2019). Besides, it can easily handle the reflective measurement model and provide more accurate results having the greatest statistical power (Hair et al., 2017). First of all, researchers evaluated the measurement model to examine convergent and discriminant validity (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). After analyzing the measurement model, the association and strength between latent variables were explored through structural model testing after controlling demographic variables Figure 2. PLS bootstrapping (number of bootstrap samples is 5000) was run through which each coefficient’s significance was evaluated (Streukens & Leroi-Werelds, 2016).

Results

The results of Table 1 showed the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Of the 650 questionnaires distributed, 600 were retrieved. Out of 600 respondents, there were 327 (54.50 %) males and 273 females (45.50%). Whereas 179 (29.87%) respondents belonged to rural areas and 421 (70.17%) respondents from urban areas. An overwhelming majority of respondents 467 (77.83%) were between 18-22 years old, 121 (21.17%) were 23-27 years, 28-32 aged people were 7 (1.2%), and more than 32 age 5 (.8%). The majority of the respondents were belonging to Punjabi ethnicity 513 (85.50%), Pashtun participants were 30 (5%), 17 (2.83%) respondents were Baloch and 40 respondents (6.67%) belonged to other ethnicities. Majority 464 (77.33%) were Ahle-Sunnat, 72 (12%) respondents were Ahle-Hadith, 33 (5.50%) respondents were Ahle-Tasih, 31 respondents (5.17%) belonged to other sects. So far as qualification is concerned, 426 (71%) were studying at Bachelor level, 141 (23.50%) at Master and 33 respondents (5.50%) were students of Master of Philosophy. 46 respondents (7.67%) were studying at Government College University, Lahore, 50 respondents (8.33%) at National University of Modern Languages, Lahore, 156 (26%) at Punjab University, Lahore, 222 (37%) respondents at University of Central Punjab, Lahore, 55 (9.17%) respondents at University of Management and Technology, Lahore, and 71(11.83%) respondents were studying at University of Education, Lahore.

| Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants | |||

| Demographics | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Gender | Male Female |

327 273 |

54.50 45.50 |

| Locale | Rural Urban |

179 421 |

29.87 70.17 |

| Age | 18-22 23-27 28-32 More than 32 |

467 121 7 5 |

77.83 20.17 1.2 .8 |

| Ethnicity | Punjabi Pashtun Baloch Any other |

513 30 17 40 |

85.50 5 2.83 6.67 |

| Sect | Ahle-Sunat Ahle-Hadith Ahle-Tasih Any other |

464 72 33 31 |

77.33 12 5.50 5.17 |

| Qualification | Bachelor Master M. Phil |

426 141 33 |

71 23.50 5.50 |

| Universities | GCU NUML PU UCP UMT UOE |

46 50 156 222 55 71 |

7.67 8.33 26 37 9.17 11.83 |

Table 2 indicated the results of the convergent and discriminant validity of reflective constructs. While evaluating reflective measurement models, most of the studies reported these things (Ringle, et al., 2020). Measurement models with reflective indicators require .70 reliability values for internal consistency reliability and composite reliability (Hair et al., 2019). All constructs have up to the mark reliability except dispositional fear of isolation and willingness to self-censor. Chin (1998) suggested that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be minimum .50 to attain reasonable convergent validity. As shown in the above table, four constructs attitude strength towards the army, attitude strength towards religion, dispositional fear, and willingness to self-censor don’t fulfill this criterion due to lower AVE. Besides, the researcher measured the discriminant validity through the criteria of Fornell & Larcker (1981). Diagonals (bold values) represent the square root of the AVE while the other entries represent the correlations. Beta values can be observed in the inner model, loading of items of different constructs in the outer model, and R2 values in constructs. The R2 value is helpful in evaluating the PLS-SEM measurement model Figure 2. According to Falk and Miller (1992), it should be at least 0.10. In the opinion of Chin (1998), the R2 value of 0.67, 0.33, and 0.19 are considered as powerful, moderate, and weak. The R2 value of willingness to self-censor is moderate and attitude strength has extremely lower R2 values.

| Table 2 Assessment of Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Reflective Constructs | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| AS Army | 0.66 | |||||||||

| AS Judiciary | 0.35 | 0.72 | ||||||||

| AS Police | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.71 | |||||||

| AS Religion | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.69 | ||||||

| CFI Army | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.80 | |||||

| CFI Judiciary | 0.16 | 0.17 | -0.06 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.79 | ||||

| CFI Police | 0.10 | 0.17 | -0.05 | -0.04 | 0.43 | 0.61 | 0.80 | |||

| CFI Religion | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.79 | ||

| DFSI | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.62 | |

| WTSC | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.57 |

| Cronbach's Alpha | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.63 | 0.66 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.77 |

| AVE | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.33 |

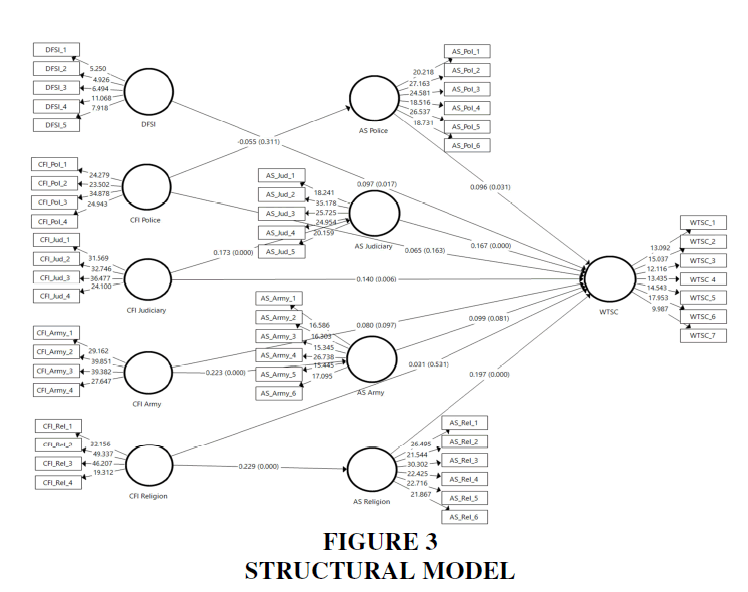

Table 3 revealed the results of this study. The results indicated a significant relationship between dispositional fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship (β=0.097, t=2.38, p= 017). H1 was supported. The relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding police and willingness to self-censorship was non-significant (β=0.065, t=1.39, p=0.163). H2 was not supported. H3 was supported as the relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding judiciary and willingness to self-censorship was significant (β=0.14, t=2.74, p=0.006). This study found no relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding army and willingness to self-censorship (β=0.08, t=1.65, p=0.09). H4 was not supported. Similarly, the association between contextual fear of isolation regarding religion and willingness to self-censorship was non-significant (β=0.031, t=0.62, p=0.53). H5 was not supported.

| Table 3 Results of the Direct and Indirect Effects | ||||

| Hypothesis Path | β | SD | t-value | p-value |

| DFSI -> WTSC | 0.097 | 0.041 | 2.38 | 0.017 |

| CFI Police -> WTSC | 0.065 | 0.047 | 1.39 | 0.163 |

| CFI Judiciary -> WTSC | 0.14 | 0.051 | 2.74 | 0.006 |

| CFI Army -> WTSC | 0.08 | 0.048 | 1.65 | 0.097 |

| CFI Religion -> WTSC | 0.031 | 0.049 | 0.62 | 0.531 |

| CFI Police -> AS Police | -0.055 | 0.054 | 1.01 | 0.311 |

| CFI Judiciary -> AS Judiciary | 0.173 | 0.048 | 3.56 | .000 |

| CFI Army -> AS Army | 0.223 | 0.043 | 5.16 | .000 |

| CFI Religion -> AS Religion | 0.229 | 0.046 | 4.95 | .000 |

| AS Police -> WTSC | 0.096 | 0.044 | 2.16 | 0.031 |

| AS Judiciary -> WTSC | 0.167 | 0.047 | 3.59 | .000 |

| AS Army -> WTSC | 0.099 | 0.057 | 1.74 | 0.081 |

| AS Religion -> WTSC | 0.197 | 0.054 | 3.66 | .000 |

| CFI Police -> AS Police -> WTSC | -0.005 | 0.006 | 0.86 | 0.386 |

| CFI Judiciary -> AS Judiciary -> WTSC | 0.029 | 0.012 | 2.47 | 0.013 |

| CFI Army -> AS Army -> WTSC | 0.022 | 0.014 | 1.56 | 0.117 |

| CFI Religion -> AS Religion -> WTSC | 0.045 | 0.015 | 3.01 | 0.003 |

The results further illustrated that there was no relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding police and attitude strength towards police (β=-0.05, t=1.01, p=0.31). Contrary to this, there was a significant relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding judiciary and attitude strength towards judiciary (β=0.173, t=3.56, p=0.000), contextual fear of isolation regarding army and attitude strength towards army (β=0.223, t=5.16, p=0.000), and contextual fear of isolation regarding religion and attitude strength towards religion (β=0.229, t=4.95, p=0.000). Moreover, a significant association was observed in the relationship between attitude strength towards police and willingness to self-censorship (β=0.096, t=2.16, p=0.03). Likewise, the relationship between attitude strength towards judiciary and willingness to self-censorship was statistically significant (β=0.167, t=3.59, p=0.000). The relationship between attitude strength towards army and willingness to self-censorship was not significant (β=0.09, t=1.74, p=0.08). However, there was a significant relationship between attitude strength towards religion and willingness to self-censorship (β=0.197, t=3.66, p=0.000).

The results of the indirect effects showed that attitude strength towards police was not a significant mediator between the relationship of contextual fear of isolation regarding police and willingness to self-censorship (β=-0.005, t=0.86, p=0.386). H6 was not supported. The results of this study supported H7 indicating the significant mediating effects of attitude strength towards judiciary on contextual fear of isolation regarding judiciary and willingness to self-censorship (β=0.029, t=2.47, p=0.01). In addition, the mediating effects of attitude strength towards the army were nonsignificant between the relationship of contextual fear of isolation regarding army and willingness to self-censorship (β=0.022, t=1.56, p=0.117). H8 was not supported. The results of this study demonstrated a significant mediating role of attitude strength towards judiciary in the relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding religion and willingness to selfcensorship (β=0.045, t=3.01, p=0.003). H9 was supported.

Apart from identifying direct and indirect relationships, this study checked the association between demographics and willingness to self-censorship. Locality (β=0.127, p=0.003) and ethnicity (β=0.082, p=0.04) were found significant predictors of the willingness to self-censorship. In the below structural model Figure 3, beta and p-values can be seen in the inner model and t-values in the outer model. A minimum of 1.96 t-values is recommended and the relationship is significant at .05 levels.

Discussion

Building on the spiral of silence theory, this study investigates the relationship between fear of isolation and willingness to self-censorship through the mediating role of attitude strength. The result derived from this study demonstrates that dispositional fear of isolation has a significant relationship with willingness to self-censorship. These results are compatible with previous studies (Chan, 2021; Chen, 2018; Fox & Holt, 2018). It is clear from these results that social media users are more willing to self-censor their views due to the fear of social isolation.

The relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding police and willingness to self-censorship is nonsignificant. This result is contrary to the study of Fox and Holt (2018). In Pakistan, social media users openly criticize ‘Thana culture’ (Traditional police culture) on social networking sites. They are even more comfortable criticizing the loopholes of police as compared to other state institutions. In 2019, Punjab Police’s Counter-Terrorism Department murdered a couple along with a Taxi driver in an encounter based on the wrong intelligence information. Social media users denounced Sahiwal killings and supported victims. So, the observed results seem compatible with ground realities.

The relationship between contextual fear of isolation regarding judiciary and willingness to self-censorship is significant. Right now, judicial activism is on the rise. Judiciary has gained a lot of power after Pakistan’s Lawyers Movement. Judges in higher courts are demonstrating their power by taking Suo Moto notices. Recently, the Supreme Court took suo moto of a video viral on social media. This video contains derogatory remarks against a judge. People fear while commenting on decisions of the judiciary because it leads them towards self-censorship. Contrary to researchers’ expectations, this study doesn’t find a direct association between contextual fear of isolation regarding army and religion and self-censorship. Future studies must take into consideration this important point and investigate this relationship in different opinion climate conditions. Powerful military establishment and religion are sacred cows in Pakistan. These two institutions are above the law. Nobody can dare to challenge the supremacy of these two institutions. Apparently, the results of military and religion seem irrational. Neuman (1974) claimed that people try to hide their true opinions when they fall into a minority group. The insignificant results may be the outcome of this proposition of a spiral framework. In addition to the loud majority and silent minority factors, researchers collected data in Lahore, the capital of Punjab. Punjabis are usually considered conservatives who have a higher inclination towards army and sympathy for militant Jihadi groups. The results will be probably different if we test this theory in other areas of Pakistan.

This study has made a little effort by investigating a psychological antecedent attitude strength that significantly predicted the willingness to self-censorship. Contextual fear has also positive effects on attitude strength. Besides, this study also observed the indirect effects of attitude strength. The results indicate that attitude strength towards judiciary and religion are significant mediators between fear of isolation and self-censorship (see Table 3). The overall results of this study have testified the authenticity of the spiral framework.

This study is limited in terms of generalizing results. This study collected data through convenience sampling technique. Due to applying a sampling technique of non-probability sampling, the results can’t be generalized to the overall population. Future studies need to generalize results by having a representative sample. Besides, it also remains for future investigations to test CFI -> AS -> WTSC under different opinion climate conditions. Future researchers should move a step forward and explore the moderating mechanism e.g. network heterogeneity. Despite limitations, this study contributes to the existing literature of the spiral of silence by investigating the mediating role of attitude strength and testing the basic proposition of the spiral of silence framework in the context of Pakistan.

Conclusion

To summarize, this study examines the fear of isolation on social networking sites regarding religious extremism and state institutions and checks its effects on willingness to selfcensorship under the framework of the spiral of silence. Furthermore, this study investigates the mediating effects of attitude strength. The results showed that dispositional fear of isolation has a positive and direct relationship with willingness to self-censorship. Furthermore, contextual fears of isolation regarding judiciary lead social media users towards self-censorship. Attitude strength significantly predicted willingness to self-censorship in all state institutions except army. This study also observed statistically significant indirect effects of contextual fear of isolation on willingness to self-censorship via attitude strength towards judiciary and religion.

References

Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Baldassare, M., & Katz, C. (1996). Measures of attitude strength as predictors of willingness to speak to the media. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73(1), 147-158.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baran, S.J., Davis, D.K., & Striby, K. (2012). Mass communication theory: Foundations, ferment, and future.

Chan, M. (2021). Reluctance to talk about politics in face-to-face and Facebook settings: Examining the impact of fear of isolation, willingness to self-censor, and peer network characteristics. In Social Media News and Its Impact (pp. 169-191). Routledge.

Chen, H.T. (2018). Spiral of silence on social media and the moderating role of disagreement and publicness in the network: Analyzing expressive and withdrawal behaviors. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3917-3936.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chin, W.W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern methods for business research, 295(2), 295-336.

Croucher, S.M., Spencer, A.T., & McKee, C. (2014). Religion, religiosity, sex, and willingness to express political opinions: A spiral of silence analysis of the 2008 US presidential election. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 22(2), 111-123.

Erichsen, E.A., & Bolliger, D.U. (2011). Towards understanding international graduate student isolation in traditional and online environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59, 309-326.

Falk, R.F., & Miller, N.B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling University of Akron Press. Akron, Ohio.

Farmer, B. (2019). Pakistan investigates journalists for online campaign to 'disrespect' Saudi Crown Prince with Khashoggi pictures. The Telegraph.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fox, J., & Holt, L.F. (2018). Fear of isolation and perceived affordances: The spiral of silence on social networking sites regarding police discrimination. Mass Communication and Society, 21(5), 533-554.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gearhart, S., & Zhang, W. (2014). Gay bullying and online opinion expression: Testing spiral of silence in the social media environment. Social science computer review, 32(1), 18-36.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Guardian. (2017). Boy, 10, killed in attempted blasphemy lynching in Pakistan. The Guardian.

Hair Jr, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

Hair, R., & JJ, S.M., & Ringle, CM (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2-24.

Hampton, K.N., Rainie, H., Lu, W., Dwyer, M., Shin, I., & Purcell, K. (2014). Social media and the'spiral of silence'(pp. 143-146). Washington, DC, USA: PewResearchCenter.

Hayes, A.F., Glynn, C.J., & Shanahan, J. (2005). Willingness to self-censor: A construct and measurement tool for public opinion research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 17(3), 298-323.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hayes, A.F., Matthes, J., & Eveland Jr, W.P. (2013). Stimulating the quasi-statistical organ: Fear of social isolation motivates the quest for knowledge of the opinion climate. Communication Research, 40(4), 439-462.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ho, S.S., & McLeod, D.M. (2008). Social-psychological influences on opinion expression in face-to-face and computer-mediated communication. Communication research, 35(2), 190-207.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Imran, M. (2017). No evidence found against bloggers accused of blasphemy, FIA tells court. The Daily Dawn.

Kushin, M. J., Yamamoto, M., & Dalisay, F. (2019). Societal majority, Facebook, and the spiral of silence in the 2016 US presidential election. Social Media+ Society, 5(2), 2056305119855139.

Lang, K. (2014). Opinion expression on social networking sites testing an adapted spiral of silence model for political discussion on Facebook. University of Miami.

Lee, H., Oshita, T., Oh, H.J., & Hove, T. (2014). When do people speak out? Integrating the spiral of silence and the situational theory of problem solving. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(3), 185-199.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, N.Y., & Kim, Y. (2014). The spiral of silence and journalists' outspokenness on Twitter. Asian Journal of Communication, 24(3), 262-278.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Matthes, J., Hayes, A.F., Rojas, H., Shen, F., Min, S.J., & Dylko, I.B. (2012). Exemplifying a dispositional approach to cross-cultural spiral of silence research: Fear of social isolation and the inclination to self-censor. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24(3), 287-305.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McDevitt, M., Kiousis, S., & Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2003). Spiral of moderation: Opinion expression in computer-mediated discussion. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 15(4), 454-470.

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail's mass communication theory. Sage publications.

Neuwirth, K. (2000). Testing the spiral of silence model: The case of Mexico. International Journal of public opinion research, 12(2), 138-159.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Noelle‐Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence a theory of public opinion. Journal of communication, 24(2), 43-51.

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The spiral of silence: Public opinion--Our social skin. University of Chicago Press.

Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S.P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617-1643.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rosenberry, J., & Vicker, L.A. (2021). Applied mass communication theory: A guide for media practitioners. Routledge.

Shahzad, M. (2019). TV anchor Rizwan Razi arrested for ‘defaming state institutions. The Express Tribune.

Streukens, S., & Leroi-Werelds, S. (2016). Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. European management journal, 34(6), 618-632.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Woong Yun, G., & Park, S.Y. (2011). Selective posting: Willingness to post a message online. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 16(2), 201-227.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zulqernain, M. (2018). Pakistani Journalist and Activist Gul Bukhari Abducted, Released in Lahore.

Received: 03-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. JOCCC-23-13413; Editor assigned: 04-Mar-2023, Pre QC No. JOCCC-23-13413(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Mar-2023, QC No. JOCCC-23-13413; Revised: 25-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. JOCCC-23-13413(R); Published: 31-Mar-2023