Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 3

Factors Influencing The Adoption And Implementation Of Customer Relationship Management Strategies By Small And Medium Enterprises In Kwazulu-Natal

Cletos Garatsa, Durban University of Technology

B.I Dlamini, Durban University of Technology

Citation Information: Garatsa C, Dlamini BI. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption and implementation of customer relationship management strategies by small and medium enterprises in kwazulu- natal. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(8), 1-18.

Abstract

Small to medium enterprises (SMEs) play an important role in the development of economiesboth in the developed and developing countries. SMEs face many obstacles in their path to survival and much has been discussed in terms of helping the small enterprises to survive and grow to fulfill their economic potential and derive the benefits that come with it. As such, many solutions have been proffered to ameliorate the demise of SMEs in their early stages of establishment. This paper wishes to harness customer relationship management (CRM) to help SMEs to survive and thrive in the harsh economic environment. CRM creates a competitive advantage that can be viewed as a panacea to SME failure. It is therefore the aim of this study examined the factors that influence the adoption of CRM by SMEs in Kwa-Zulu Natal (KZN).The goal is to move away from the misconception that CRM is a technology but gravitate towards treating CRM as a holistic strategy that should diffuse within the whole organisation. Organisational, environmental, technological and information culture factors should all be integrated and help the firm to make a well-informed decision when it comes to adopting CRM strategies. The scope of this paper is further motivated by the fact that there is a paucity of studies that investigate the adoption of CRM by SMEs in KZN CRM adoption and implementation are not without their problems, but the promises are too good to ignore; and, indeed, the future prosperity of SMEs may lie in CRM adoption and implementation.

Keywords

Customer Relationship Management (CRM), Small, Medium Enterprises (SMES), Kwa-Zulu Natal (KZN)

Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are an important fabric of any economy (Hassan, Mohamed Haniba and Ahmad 2019; Hasani et al., 2017; Awiagah et al., 2016 ; Sudhakar, 2015; Bahri-Ammari & Nusair, 2015) and even more paramount when it comes to their status in developing and emerging economies especially in the African context (Ayandibu & Houghton 2017). This is further supported by Fatoki (2014) who argued that new SMEs play an important role in solving challenges of joblessness, unequal income distribution and stimulating sustainable economic. The Ministry of Small Business Development (2015) noted that SMEs played a vital role in the development of the South African economy, contributing more that 45% to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 50% of employment opportunities (Lekhanya, 2015). SMEs are considered to be so important such that failure viewed as failure to the whole economy (Worku, 2013) which is why the government actively supports the growth and sustenance of SMEs (SEDA 2016).

Many eminent scholars have delved into a plethora of problems and challenges facing SMEs across the globe and in South Africa (SEDA, 2016; Abu-Dalbouh, 2013). A review of literature on SME development shows that lack of funding is one of the major reasons that curtails SME establishment and development. Arguably, a number of obstacles have an impact on the development and sustainability of SMEs on the African continent, most notably limited access to markets, poor financial resources, lack of public sector support, a static business environment that is overregulated and severe infrastructural deficits (especially power outages) (Gonsalves & Rogerson, 2019; Schmidt et al., 2016). Failure to attract and retain customers is one of the problems attributed to the failure of SMEs. Does it mean that SMEs have not attempted to customer retention strategies? Attempts have been made in this sector to use Customer Relationship Management (CRM) to avert failure. The question therefore is whether CRM is a panacea or a Pandora’s box.

CRM is not often considered a strategy for SMEs, but the truth is that owners have a close relationship with the customers which is a source competitive advantage for SMEs (Meyliana et al., 2017; Starzyczná et al., 2017). It reflects a new school of thought that takes place at the junction of CRM strategies and SMEs; that is, the scholars are trying to comprehend the boundaries of CRM. The critical question being asked is where CRM kicks in and where it ends. Garcia, Pacheco and Martinez (2012) reiterated that CRM in SMEs indicates that research is based, mainly to a large extent, on the knowledge gained from large corporates and, therefore, focuses on their characteristics. This paper endeavours to move away from the common trajectory of cloning CRM strategies from large organisations on SMEs and lead to the development so SME specific CRM strategies. CRM strategies, which are meant to propagate consumer interaction during the design, production and delivery of goods and services may determine the success or failure of new enterprises (Hasani et al., 2017). There is a paucity of research considering the adoption and implementation of CRM strategies despite the considerable benefits that SMEs in KZN can derive from CRM adoption and implementation (Cruz-Jesus et al., 2019). SMEs in KZN have been struggling for a long time and many solutions have been proffered but to no avail. This paper therefore proposes to use CRM as a solution to help SMEs to break out of the vicious cycle of extinction before their second birthday. The adoption of CRM strategies will therefore amplify the benefits that SMEs bring to the economy and the local communities (Galvão et al. 2018b) as well as consolidating the government’s policy initiative of using SMEs as a tool to eradicate poverty and underemployment (Maziriri & Chivandi, 2020).

Paraschou (2016) argued that CRM may provide numerous opportunities to SMEs as it does in large organisations. A deeper understanding of the factors that drive and influence the successful adoption and implementation of CRM strategies to enhance competitiveness within the sector is needed, thus this becomes the launch pad of this study. SMEs are different from large organisations especially their limited financial muscle which has a negative bearing on their information-seeking practices, and they do not encounter the same problems of integrating old and new technology in CRM programmes. Therefore, the adoption of CRM in SMEs should not be viewed as a shrunk version of bigger firms (Alshawi et al., 2011). The research on CRM within the academic literature has mainly focused on installation factors such as Internet Technologies (IT) rather than factors that influence when, how, and why firms adopt CRM (Sudhakar, 2015). Therefore, it is essential for this research to move away from the focus on software to internal and external factors and other technological aspects within and across the organisation. To copiously comprehend the latent ability of SMEs, the SME sector needs to be tackled with a new perspective related to the challenges that SMEs are confronted with. Therefore, the emphasis needs to be taken away from the available collateral in the enterprise to the viability of the business and the capability of the businessperson.

This research therefore endeavours to recognise and authenticate the major factors that directly or indirectly interact with the adoption and implementation of CRM strategies by SMEs. By so doing, the study seeks to provide a thorough and broader grasp of CRM concept in SMEs, which will allow other researchers to relate their experiences to the output of this study and to give guidelines to CRM practitioners responsible for adoption and implementation of CRM applications. A critical analysis of how CRM can be successfully adopted and implemented by SMEs in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) in their quest for growth and survival thus needs to be undertaken. The current research mainly investigated SMEs registered and funded by the Department of Small Business Development, supported by Durban University of Technology (DUT) at the Centre for Social Entrepreneurship (CSE).

Literature Review

Understanding the Concept of SMEs

The absence of a universal definition generates an uncertainty in the terminology used to describe small, medium and micro-enterprises as evidenced over the past 30 years (Anastasia 2015). As a result, a noticeable element in the literature is the multiplicity of terminologies used to describe enterprises that are not categorised as large firms, corporations or publicly owned enterprises (Gopaul, 2019). According to Anastasia (2015), the existence of the large variation in the definition and classification of small businesses illustrates the challenges encountered by international authorities as well as researchers in reaching a common benchmark on which to calibrate any statistics. The European Union (EU) the United Kingdom (UK) and international organisations such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the World Trade Organisation, the World Bank and the United Nations (UN) commonly use the abbreviation “SME” to refer to small and medium-sized enterprises (Gopaul, 2019). The term “small and medium businesses” or “SMBs” is mainly used in the United States of America (ILO 2013). In Africa, generally, Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) is typically used; however, South Africa uses the abbreviation “SMME” for small, medium, and micro-enterprises (South Africa NCR 2011). The acronym, SME is used in this research in preference to any of the other terms.

Defining the SME

Prior arguments have brought to the fore that fact there is plurality of definitions when it comes to SMEs. In various countries, South Africa included, multiple definitions of SMEs have been postulated, which is a concern to the academics and policy makers (Roopchund, 2019; Lekhanya, 2016; Soni et al., 2015). There is no consensus and uniformity in defining an SME (Jassim & Khawar, 2018; Berisha & Pula, 2015). The absence of a universal definition generates an uncertainty in the terminology used to describe SMEs as evidenced over the past 30 years (Anastasia, 2015). Industries are unique in nature such that one characteristic has various meanings to different industries compounding the efforts to come up with a universal definition (Soni et al., 2015).

The existence of the large variation in the definition and classification of SMEs illustrates the challenges encountered by international authorities as well as researchers in reaching a common benchmark on which to calibrate any statistics (Anastasia, 2015). The number of people in employ, sales figures, and profits are some of the factors that have been incorporated into the official definition of SMEs (Pohludka & Štverková, 2019). The common parameters used to define SMEs are factors such as size, number of employees and turnover bands (ar Jassim & Khawar, 2018). Scholars have tried to use these factors to harmonise and synthesise the definition of SMEs (ar Jassim & Khawar, 2018; Kunene, 2014). Businesses are different when it comes to capital requirements, sales volumes, and employment numbers. Hence, definitions which utilise size (net worth, profitability and employment numbers) could result in most of the business being categorised as small while a different result can be obtained when applied to another sector (Berisha & Pula, 2015). The key quantitative measure utilised by the World Bank to define SMEs are total value of assets, sales per annum measured in American dollars and number of employees (Berisha & Pula, 2015). An enterprise must therefore satisfy the standards of number of workers and either the total asset value or sales per annum for them to be classified as SMEs. The meaning considered the small enterprises sector to be uniform in their characteristics; however, businesses do not follow the same path of growth.

Khedhaouria et al. (2015) identified traits of the small enterprise other than size. The qualitative approach to defining the SME takes into cognisance the fact that SMEs have a limited clientele and product base as well as uncertainty attached to diversity of aims and objectives in comparison to big firms (Majama & Magang, 2017) they are forced to be price takers (Bharati & Chaudhury, 2015). The Bolton Committee’s economic definition entails that a firm is characterised as small if it has a comparatively diminished share of the market place, owner-managed or part owners in a personalised way (Berisha & Pula, 2015), and not through the medium of a formalised management arrangement, and not being in partnership with large firms (Pratt & Virani, 2015; Dalitso & Peter, 2000). However, the economic definition was criticised for assuming that small firms operate in a flawlessly competitive marketplace. The issue of perfect competition is not a reality for SMEs, many small enterprise occupy niches providing a highly specialised goods and service in a geographically isolated area with little or no competition (Pratt & Virani, 2015; Dalitso & Peter, 2000).

The problems that arise from the statistical and qualitative definitions of SMEs are also rampant in South Africa. The government came up with a definition that encapsulated the quantitative and qualitative definition of the small enterprise. However, the owner-manager is of paramount importance. Section 1 of the National Business Act of 1996, which was as amended in 2003 and 2004 officially defines a small business as:

A separate and distinct business entity, including cooperative enterprises and nongovernmental organizations, managed by one owner or more which, including its branches or subsidiaries, if any, is predominantly carried on in any sector or sub-sector of the economy mentioned in Column I of the Schedule 14. (Republic of South Africa 2019; Cant & Rabie, 2018; DTI, 1996).

For the purpose of this research, the author has adopted the definition that was proffered by the DTI (1996) which places the owner at the centre of the business and includes cooperatives. This is imperative because the aim of the study is to investigate SMEs that are situated in the KZN province of South Africa. This is also in line with the objectives of the research because owner characteristics play an important role in the decision to adopt CRM.

The Importance of SMEs

The importance of SMEs for the economic upturn of both developing and developed nations is widely recognised and there is abundant literature and research studies in support of the above notion (Stankovska et al., 2016; Soni et al., 2015). Indeed, SMEs have been acknowledged as engines to achieving development objectives of third world countries because they easily adapt to customer needs, mobilise idle funds, employ from local communities (Adeyele & Omorokunwa, 2017). The prospects of sub- Saharan African development are pinned on the positivity than can be generated by SMEs (Gonsalves & Rogerson, 2019). Adeyele and Omorokunwa (2017) further argued that local economies cannot effectively develop without the active role of SMEs that influence the commercial activities in any nation. Studies by Sharma (2018); Muriithi (2017); Saleem (2013) in the Middle East and North Africa found out that registered SMEs contribute up to 45% of job opportunities and up to 33% of GDP in budding economies. Research work carried out by Hendrayati and Syahidah (2018) indicated that SMEs have a very important role in the Indonesian economy. Onyenego (2018) documented that 63% of new jobs is accounted for by SMEs thus they represent 99.7% of all employers in the United States. Basing on the Kenyan experience, Osano (2019) argued that SMEs play a complementary role to large organisations as auxiliary units; they are more flexible than big business and can thus effectively meet the needs of the population.

SME failure

However, a huge number of SMEs are reported to close before the fifth year of establishment (Adeyele & Omorokunwa, 2017). Due to the important role they play any economy (Lekhanya, 2016), failure by SMEs is viewed as failure of the whole economy, and the government actively supports the growth and sustenance of SMEs (Peter et al., 2018; Leboea 2017). The high rate of failure newly established SMEs portrays hopeless images of the SME sector’s potential to meaningfully contribute to employment creation, economic development and poverty alleviation (Peter et al., 2018). The best way to reduce poverty is to promote economic growth through increasing the number of SMEs that create employment opportunities (Guzmán & Lussier, 2015). The formal economy is not creating enough jobs resulting in high rates of unemployment (Page & Shimeles, 2015). The success of SMEs could have contributed to solving the unemployment problem (Maziriri & Chivandi, 2020) thus the effect of their failure is sorely felt. Despite the documented high rate of failure, new SMEs are being registered and resources are being channeled into the new SMEs (Bruweret al., Gono et al., 2016; Jere et al., 2015). It therefore begs the question as to why resources are continuously being channeled towards SMEs (Bruwer, 2017). This strengthens the growing belief that SMEs are key propellers of economic growth (Kachlami & Yazdanfar, 2016; Nag & Das, 2014).

CRM has often been hyped as a tool to gain competitive advantage in the market (Amalnick & Zadeh, 2017) but it can also be a reason for SME failure if it is not properly implemented. There is overwhelming consensus that CRM is a strategic imperative, but scholars and CRM practitioners have noted with concern that the return on investment on CRM initiatives vary across industries and organisations (Junkala, 2017). In fact, the increase in the number of failed projects is frightening (Ali et al., 2015). However, it must be noted that this section has only highlighted the fact that CRM can be the reason for SME failure; further details are provided in the CRM section below. The researcher is encouraged by conclusions drawn from Rigby, Reichheld and Schefter (2002) who argued there is hope that, even if organisations have been unsuccessful at implementing CRM. The promises of CRM are too good to ignore.

Understanding the Concept of CRM

The earliest forms of CRM can be tracked down back to early forms of civilisation and trade (Payne & Frow, 2006). Traders had developed very close personal relationships with their customers such that they knew their buying patterns and how much they were willing to spend (Starzyczná et al., 2017). Efficient and mutually beneficial relationships were born out this thorough understanding of the customers (Garcia et al., 2012). However, understanding of customer needs was eroded by the rapid and continuous movement of people, growth of cities, industrialisation and the commercialisation scope was increased (Garcia et al., 2012). The decline in customer loyalty and an increase in competition have necessitated the need for new strategies to woo the customers and starve off competition by delivering personalised services and goods (Wolter et al., 2017). CRM therefore enables the organisation to single out profitable customers to meet and exceed their expectations to forge an enduring relationship with the firm (Amalnick & Zadeh, 2017). This win-win relationship can be achieved through the provision of cost-effective, enough products for all the customers using the most suitable means at the right time at (Garcia et al., 2012). This relationship proposition can further be strengthened by encouraging symbiotic relationships and repeat sales to the customer (Roopchund, 2019; Amalnick & Zadeh, 2017). The ultimate aim of CRM is to develop sustainable, long-term relationship with a few chosen clienteles. CRM can be viewed as a means to an end; that is, to gain an advantage over competitors, especially from the angle of managing relationships with the consumer and providing better customer service (Ahluwalia, 2017). To achieve the profit maximisation objective, target consumers are carefully selected and reached out to before the product is developed to identify the customer needs. This ensures that the product meets the needs of the clients while the firm makes profit (Chaudhry et al., 2019).

Defining CRM

CRM is widely accepted in the professional circle, however there is no unanimity when it comes to defining the concept (Amalnick & Zadeh, 2017; Askool & Nakata, 2010). Despite the phenomenal evolution, the concept of CRM is still incomplete and growing (Athanasoulias & Chountalas, 2017). The problem is exacerbated by the fact that CRM is relatively a new discipline (Elbeltagi et al., 2014; Rahimi, 2005). Scholars have claimed literature does not provide a meticulous meaning of CRM thus there is continuing debate as to what it entails (Rahimi & Gunlu, 2016; Venturini & Benito, 2015). What really constitutes a CRM programme remains elusive. Another logic for the complexity in defining CRM arises from the fact that it is multidimensional (Junkala, 2017). Even though CRM is a fairly new concept (Rahimi, 2005), several reasonable definitions were provided through the years in an effort to encapsulate the meaning of this multidisciplinary term (Cruz-Jesus et al., 2019; Athanasoulias & Chountalas, 2017; Askool & Nakata, 2010). An agreed and precise meaning of CRM is needed regardless of the raging debate.

Traditional CRM is viewed as set strategies, systems, philosophies supported by technology to efficiently and effectively manage the interactions between organisations and its customers to develop and maintain profit maximisation portfolio of consumer relationships (Bahri- Ammari & Nusair, 2015; Nguyen & Waring, 2013). In general, CRM is made up of a combination of technologies, philosophies and business practices that endeavour to ascertain the behaviour and characteristics of the customer to retain them and improve sales performance (Sota et al., 2018; Amalnick & Zadeh, 2017). CRM can also be described as a general process of creating and refining interactions between organisations and consumers with a view to maximising the overall customer satisfaction and lifetime value (Roopchund, 2019). Even though CRM has been defined in diverse ways depending on one’s point of departure, however most definitions emphasise customer-centredness, applying the Pareto-principle (Pareto, 1848- 1923) cited by Elbeltagi, et al. (2014) which is often referred to as the principle of the fundamental few and trivial many. It contents that 80% of the results is obtained from 20% of the known variables. Thus, CRM can be defined as an integrated approach that aims to develop an in-depth understanding of clients and is premised on consumer relationship development and customer retention (Marolt, 2018). This definition is very important for this research because it takes into consideration the various factors like the organisation, technology, information culture and the environment that can influence the adoption and implementation of CRM strategies. It therefore sets the parameters and context of the research.

CRM Benefits

1. Improved consumer loyalty

2. Enhanced consumer profitability

3. Reduced costs of customer acquisition

4. More effective marketing

5. Enhances consumer support and services

6. Reduced costs and increased efficiency

7. High rate of customer retention, loyalty and satisfaction enhanced by quicker resolution of customer problems

8. No need to acquire a lot of consumers to preserve a steady sales volume

9. Centralised customer contact

10. Improves return on marketing investment

11. Acquiring well-accepted outcomes of data-mining activities.

CRM models

Literature on describes two broad approaches to CRM which are operational and strategic. The former has not been extensively researched on while the later has received a lot of attention (Elbeltagi et al., 2014). However, some scholars (Cruz-Jesus et al., 2019) have argued that collaborative and analytical CRM can also be explored as the other approaches so as to fully appreciate the concept of CRM. Marolt (2018) reiterates the four dimensions: collaborative, analytical, strategic and operational. Scholars argue that the strategic approach to CRM is mainly concerned with improving or creating value for the shareholder by developing appropriate long-term relationships with selected customers (Pedron et al. 2016). It focuses on the development of customer-centred organisational culture to acquire and retain customers (Marolt, 2018). CRM can therefore not only be considered a technological tool but can also be viewed as a way of enhancing organisational profits by developing sustainable relationships with consumers.

Operational CRM, concentrates on the point of interaction with customer (Starzyczná et al., 2003). Marolt (2018), retorted that operational CRM deals with the automation of the customer interaction process to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of everyday customer touch point operations. Improvement in transactional accuracy through sales force, marketing and sales automation (Marolt, 2018) aims at reducing bureaucracy and operating costs (Elbeltagi et al., 2014). Scholars noted that analytical CRM IS an extension of operational CRM using analytical statistical tools is called analytical CRM (Marolt, 2018). Analytical CRM helps the organisation to develop a thorough understanding of customer behaviour, anticipate future buying behaviour through the utilisation of business information applications such as data mining (Cruz-Jesus et al., 2019). Accurate and current customer should be made available to all organisational employees to support their decision-making process (Starzyczná et al., 2017). The collaborative CRM on the other hand focuses on the integration of all channels of communication between the consumers and the enterprise (Marolt, 2018). It facilitates and coordinates all the business within the supply chain and departments within the organisation to work together and share valuable information about the customers (Starzyczná et al., 2017). It is the so-called management of partner relationship.

CRM components and adoption stages

Rahimi (2017) noted that the three major components of CRM are technology, people, and processes. Successful CRM implementation of CRM results from the seamless integration of these three major components. In addition, maintaining the right balance between these important organisational resources enhances the chances of CRM success (Rigo et al., 2016). Organisations can therefore achieve high levels of customer loyalty, retention, and satisfaction by effectively combining and working with the aforementioned resources. (Chen & Popovich, 2003).

According to Puklavec et al. (2018), there are various stages involved in the IT innovation adoption process. These stages maybe viewed as standalone processes but is very important to take into cognisance that they are interdependent variables. CRM literature postulate three stages of innovation adoption but there is no consensus when it comes to naming the stages (Cruz-Jesus, Pinheiro & Oliveira, 2019). The initiation stage involves the evaluation of benefits and attitudes towards or against CRM adoption are also evaluated at this stage. (Cruz-Jesus et al., 2019; Puklavec et al., 2018). The adoption stage involves the mobilisation of the necessary resources for integration and implementation, reorganization of the business processes and reconfiguration of systems once the decision to accept CRM implementation is made (Chiu, Chen and Chen 2017). The final stage called routinisation involves the actual implementation of the CRM strategy and integrating it with the existing IT within the organisation. The enterprise will have to do a trial run of the new system to test compatibility, solve the teething problems and train all staff, especially the frontline.

CRM in the SME Context

The SME sector needs to be approached with a new perspective suited to the challenges it faces to fully fathom the challenges they face and to realise its full potential. There is a need to shift the focus away from the available collateral in the business to the viability of the business and the ability of the business owner. SMEs have been perceived to be one of the fastest-growing segments of any economies, and more entrepreneurial in terms of structure and philosophy than larger enterprises (Hasani et al., 2017). Thus, their role so SMEs in any economy can never be overlooked and the differences between small and large organisations cannot be ignored (Damayanti et al., 2019; Stankovska et al., 2016). CRM can therefore be a strategic tool for SMEs. It is therefore prudent for SMEs to integrate CRM business practices into their daily business operations to gain competitive edge (Salah et al., 2019).

CRM is not often considered a strategy for SMEs, but the truth of the matter is the SMEs usually derive competitive advantage from their closeness to customers (Meyliana et al., 2017; Starzyczná et al., 2017). Galvão et al. (2018) argued that there are advantages to being small like employee loyalty, easy access to client information, flexibility and quick response, customer interface and opportunity-focus. Roopchund (2019) was of the view that SMEs carry out an informal type of CRM as opposed to the one prescribed in marketing theory. Garcia, Pacheco and Martinez (2012) reiterated that CRM in SMEs has not been widely studied, thus the study is, to a large extent predisposed on the characteristics and guided by the experiences of large organisations. Previous research on CRM has focused on big enterprises while CRM implementation in the context of SME is under-whelming and there is a limited number of scholarly work that directly addresses CRM in SME context (Hasani, Bojei and Dehghantanha 2017; Paraschou 2016). Scholars like (Galvão et al., 2018; Garcia et al., 2012) argued that CRM was developed for large firms which usually have a huge clientele database. This is not a restriction for its adoption in SMEs, because of its size (number of employees and asset value) and budget which enables them to manage a huge client base (Garcia, Pacheco and Martinez 2012). CRM projects in small companies are characteristically narrow in scope and are usually deployed in a modular fashion but they provide numerous opportunities to SMEs as it does in large organisations (Roopchund, 2019; Galvão et al. 2018).

Factors influencing the adoption and implementation by SMEs

A firm’s drive to adopt CRM technology and change the course of its marketing strategy is largely influenced by technological, organisational, and environmental factors. Just like in the corporate environment, the adoption by SMEs is largely influenced in the same way. From an administrative and strategic perspective, SMEs are ‘organic’ and are largely considered to an extension of the entrepreneur’s own personality (Stankovska et al., 2016). The Technology-Organisation-Environment (TOE) concept explains the firm’s efforts to adopt technology and change its processes (Azevedo, 2013). The TOE framework is of paramount importance because it augers well with the goal was of moving away from the misconception that CRM is a technology but gravitate towards treating CRM as a holistic strategy that should diffuse within the whole organisation. The TOE therefore allows us to investigate internal and external factors that influence the adoption and implementation process.

Critical success factors for CRM (CSFs)

CRM adoption may not yield the desired results due to a number of reasons hence it is vital to evaluate the critical success factors of CRM implementation (Ali et al., 2015). In order to appreciate critical success factors (CSFs) in a CRM implementation, it is prudent first to distinguish the success factor and its meaning (Sablan et al., 2017). Meyliana et al. (2017) identified a success factor as the limited number of areas that when satisfactory applied will considerably enhance the competitive ability of the enterprise. According to (Garcia, Pacheco and Martinez 2012), CSFs arise from a methodology that zeroes in on identifying variables that are crucial for a firm’s success, and the absence of these variables could lead to organisational failure. The success of CRM strategy depends on striking the right balance among the three fundamental enterprise resources, such as technology people, and processes (Rigo et al., 2016).

Methodology

Research design

The crux of this paper is to identify and examine the significant factors that influence the adoption and implementation of CRM strategies by SMEs by utilising the quantitative research design. The research used a quantitative approach because it made it easier and quicker to reach out to respondents (Dawson, 2007). Desai and Potter (2006) posited that the researcher can develop a clear focus on specific hypothesis and questions. Miles (2013) noted that a quantitative methodology can be utilised in exploratory studies, when dealing with complex studies than require a yes or no hypothesis. The quantitative method was therefore suitable for the purpose of this study because the research questions reflected on the factors that affect the implementation and adoption of CRM strategies by SMEs. A systematic review of similar studies showed that scholars have used quantitative research (Patole, 2019; Ali et al., 2015) also used the quantitative approach to examine the major factors influencing the adoption of CRM by SMEs in Malaysia.

Data collection methods

The research adopted quantitative research analysis to evaluate the major factors affecting KwaZulu-Natal SMEs in the process of adopting and implementing CRM programmes. To address this problem adequately, a structured questionnaire (Josiah & Nkamare, 2019) adapted from Salah et al. (2019) was designed based on the TOE framework. A questionnaire comprising 26 questions was used as the survey instrument to collect the data. The basic five-point Likert scale with scores ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree was used to gauge the responses of the participants. The administration of the questionnaire was made easy by the use of Likert scale as it is easy to understand and respondents feel at easy to provide their perception without explaining themselves too much (Subedi, 2016). The 5-point scale was also chosen because it gives the respondents the opportunity to be neutral than being forced into settling for a response which makes them uncomfortable. The questionnaires were distributed to the SMEs and it took about three months for the responses to come back. Constant reminders were sent to the participants to remind them to answer the questionnaire and its importance to the study. The questionnaires that were partially answered were discarded. The raw data was classified into numerical codes to extrapolate meaning from the data as this facilitated measurement comparisons and data conversion (Blair, 2015). This coding allowed the use of analytical software like SPSS in the analysis. The accumulated data was subjected to multiple regression and correlational analysis (Rahimi & Gunlu, 2016).

Reliability and validity

Due consideration was done in coming up with reliable and valid data collection and analytical tools to gather information. The data collection tool was circulated among industry experts, academics and peers to check if it covered all aspects of the study objectives. This led to the re-phrasing and changing the order of questions. This is in line with the assertion made by (Creswell & Creswell, 2017) that validity checks must be carried out to assess whether useful and meaningful deductions can be drawn from the research instrument. A sum total of 10% of the 384 planned population of interest (Marczyk et al., 2005) was used in a pilot study to ensure validity. The results of the pilot study showed that part of the data set that was chosen did not elicit all the information that was needed to best answer the research question, thus part of the data set was discarded, and some questions were combined. It was also noted that most of the respondents spent about 15 minutes to answer the questionnaire. It was further observed that most of the respondents did not respond to the questionnaire as soon as they got it, thus constant reminders had to be sent to get the responses from them.

It was noted by Creswell and Poth (2016) that the repeatability and consistency of a research instrument is of paramount importance. The rationale behind reliability is that any significant findings must not be once off. The same study or research carried out under the same conditions must yield the same results; thus, repeatability is vital (Kothari, 2017). The researcher made sure that all variables were adequately measured and pre-tested (Neuman, 2014) with the general population for validity and the results were not part of the actual study. The reliability coefficient of the data collection instrument was checked using the Cronbach alpha test. It is extensively used in research studies to assess reliability (Abed, 2020). Cronbach alpha is a measure of the internal reliability of consistency among various items, ratings or measurements (Bujang et al., 2018). The values range from 0-1, indicating that variables with higher numbers measured the same aspects while those with lower values mean that they did not gauge the same dimensions (Bujang et al., 2018). Variables with a statistical significance value of 0.05 or above were considered to be internally reliable for this study (Rahimi, 2017).

Data analysis

The participants’ responses gathered through the survey instrument were presented. The raw data was coded to derive meaning from the key features to facilitate measurement comparisons and data conversion (Blair 2015). This coding allows the use of analytical software like SPSS in the analysis. The statistical package, SPSS version 25, was used to analyse the accumulated data. The study ran a t-test for equality of means to check the statistical independence of variables. Descriptive, inferential statistics and logistic regression were also used to analyse and present the research findings. Conner (2017) noted that descriptive statistics provide the researcher with brief synopsis and observations about a particular set of information that are ease to digest. Descriptive statistics on their own cannot suffice to make an informed and reliable conclusion about a study; thus, other methods of analysis like inferential analysis need to be used. Inferential statistics use data from a randomly selected sample to describe and generalise for the whole population (Gibbs, Shafer and Miles 2017; Ali and Bhaskar 2016). This approach also allows inferences and comparisons to be made from research data (Simpson 2015). Bradley and Brand (2016) added that inferential statistics can be used to accept or reject a research hypothesis.

Population and sampling

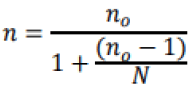

The sum total units of analysis about which the researcher wishes to use to make particular deductions was defined by Welman, Kruger and Mitchell (2005) as a population. As such, this study is guided by (SEDA 2020) report which showed that 400 967 SMEs operate within KZN. This therefore was the target population of this study. Following (Israel 1992), the sample size was calculated using Equation below:

(1)

(1)

Where, n is the sample size, N the population size and no is defined by Z2pq, here Z2 is the desired confidence interval, p is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in the population, and q is 1 - p and e is the margin of error (Israel, 1992). It must be noted that the sample size was calculated based on the proportion and not based on the mean value because the calculation of the sample size for the proportion generally will produce a more conservative sample size than will be calculated by the sample size of the mean (Israel, 1992). Given that the population of SMEs in KZN is 400 967; therefore, the sample size for the study was 384. Out of the 384 questionnaires that were sent out, 193 usable responses were received, a response rate of 50.3% usable questionnaires. This is more than the 27% response rate obtained by Gono et al. (2016) who conducted a related study on SMEs situated in Johannesburg. It must be noted that 63 responses were deleted because they were incomplete and of low quality. Rigorous checks were done to ascertain the quality of the questionnaires.

Ethical considerations

The researcher signed documentation disclosing commercial interests as a means of minimising conflict of interest prior to the commencement of the study. For the questionnaire, a consent form (Miles 2013) was developed written in simple language. The purpose of the study was explained and why the respondents were chosen to participate giving them a clear idea of what to expect, as well as any benefits to the respondents or to others. Participants were reassured of confidentiality of the findings (Snyder 2016). The researcher clarified and emphasised that the participants were at liberty to withdraw from the survey at any given time. All risks involved in this study, if any, were highlighted beforehand, be they of a financial, psychological or social nature. All necessary steps were taken to ensure that no physical harm was suffered by anyone during this research (Markwei and Tetteh 2020). The researcher was granted an ethical clearance and the gate-keepers letter part of the research process.

Limitations of the study

The research was confined to SMEs registered and funded by the Department of Small Business Development, supported by DUT at the CSE and was limited to KwaZulu-Natal. Thus, the results may not be a true reflection of all SMEs in KwaZulu-Natal and all SMEs in South Africa. The research cannot be generalised to other SMEs in other provinces. In mitigation of the above limitation, the study investigated a wide spectrum of sectors within the province. Future research can test the TOE framework on the wider KZN population including those not under incubation programmes. This study examined the whole SME sector. It would be interesting to examine one sector and post-adoption research studies can be undertaken.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics

This chapter presents the analysis of primary data that was gathered with aim of examining the factors that influence the adoption and implementation of CRM strategies by SMEs in KZN. A questionnaire that had 26 questions was used as the survey instrument to collect the data. The researcher received 193 responses out of the 384 questionnaires that were sent out, a response rate of 50.3%. Gono et al. (2016) who carried out a related study in Johannesburg had a response rate of 27%. The raw data was classified into numerical codes to derive meaning from the key features and this facilitated measurement comparisons and data conversion (Blair, 2015). This coding allowed the use of analytical software like SPSS in the analysis. Many researchers have acknowledged that descriptive statistics are a vital part of the presentation and discussion of research findings (Turner & Houle, 2019).

Inferential statistics

Inferential statistics use data from a randomly selected sample to describe and generalise the results for the whole population (Gibbs et al., 2017; Ali & Bhaskar, 2016). Inferential statistics are also used to draw conclusions and to make comparisons from the research data (Simpson, 2015). Inferential statistics were vital for this study because they helped to answer the research question, examine the design of the study and validate the measuring instrument (Simpson, 2015). The study ran a 2-tailed t-test for equality of means to check for statistical independence and that the responses were not by chance.

The technology construct had an average total alpha coefficient of 0.89 which is higher than the minimum threshold of 0.50 which was considered to be acceptable (Consonni & Bertazzi, 2017). This therefore means that the minimum standards were met for the questionnaire to be considered valid. This is in line with the results that were obtained by Rahimi and Gunlu (2016) who carried out a study on CRM adoption in the hotel industry in the UK. All the variables in this construct had a p-value < 0.05 which is within the cut-off point, meaning that the results can be generalised across all SMEs in KZN.

This organisational context construct had an average total alpha coefficient of 0.91 higher than the minimum threshold of 0.50 which was considered to be acceptable (Consonni & Bertazzi, 2017). This, therefore, means that the questionnaire met the minimum standards to be considered valid. This is in line with the results that were obtained by Rahimi and Gunlu (2016) who also obtained a coefficient that was above 0.70 meaning that the content validity was sufficient. All the variables in this construct had a p-value < 0.05 which is within the cut- off point meaning that the results can be generalised across all SMEs in KZN.

The environmental construct had an average total alpha coefficient of 0.39 which is less than the minimal accepted threshold of 0.50 suggested by Nunnally (1994). It was argued that an alpha coefficient that is less than 0.50 is too weak to be reliable (Dubey & Sangle, 2019). This therefore means that the minimum standards were not met for the construct and its variables to be considered valid. The test for independence gave a result of >0.05 meaning that the result of the study on this construct cannot be generalised for all SMEs.

Conclusion and Recommendations

A review of literature on SMEs and CRM revealed the SMEs do not have clear CRM strategies in place. It was noted the small enterprises do not have a clear CRM strategy but practise ‘implicit CRM’. The nurture of the organisational and operational structure makes it easy for SMEs to develop intimate relationships with their customers such that they know each other by name which somewhat acts as a customer data set. This, therefore, makes it easier to customise service and product offerings. The study outcomes revealed that education was one of the major drivers of CRM adoption among the SMEs that were investigated. CRM has been acknowledged to play an important role in the success of big organisations because it is a strategy that is usually customised, thus hard to replicate. CRM should therefore be viewed in the context of the SME setting not as a transplant of the corporate version of CRM. It was noted that SMEs face many obstacles in their path to survival and much has been discussed in terms of helping the small enterprises to survive and grow to fulfil their economic potential and the benefits that come with it.

CRM should be adopted in an incremental manner not as a piecemeal approach to allow integration between the new innovation and the current needs and culture of the enterprise. Simple technology can be used in the adoption and effective implementation of CRM strategies. An interesting finding from the study is that the education is one of the main drivers of CRM adoption, therefore increased awareness and educational programmes around adoption and implementation will deal with the phobia for change and technology within the small enterprises. It is also recommended that CRM practitioners from large organisations need to take a leading role in helping upcoming firms to develop an in-depth understanding of CRM. This can be initiated by incubators as part of their networking programme. Owner-managers of small enterprises can be attached to corporates so that they can get a real feel for CRM in action and twinning local SMEs with overseas firms that have succeeded with CRM can be beneficial to the local SMEs.

References

- Abed, S.S. (2020). Social commerce adoption using TOE framework: An empirical investigation of Saudi Arabian SMEs. International Journal of Information Management, 53, 102118.

- Abu-Dalbouh, H.M. (2013). A questionnaire approach based on the technology acceptance model for mobile tracking on patient progress applications. Journal of Computer Science, 9(6), 763-770.

- Adeyele, J. and Omorokunwa, O. (2017). Risk appetites and empirical survival pattern of small and medium enterprises in Nigeria. The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 18

- Ahluwalia, G.P.K. (2017). CRM–A tool for success in FMCG Sector. International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM), 3

- Ali, Z., & Bhaskar, S.B. (2016). Basic statistical tools in research and data analysis. Indian journal of anaesthesia, 60(9) 662.

- Ali, Z., Ishaya, I. and Hassan, H. (2015). The critical success factors of e-CRM implementation to small and medium enterprises. 58-62.

- Alshawi, S., Missi, F. and Irani, Z. (2011). Organisational, technical and data quality factors in CRM adoption— SMEs perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(3), 376-383.

- Amalnick, M.S. and Zadeh, S.A. (2017). Concurrent evaluation of customer relationship management and organizational excellence: an empirical study. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 30(1), 55-88.

- Anastasia, C. (2015). Exploring Definitions of Small Business and Why It Is so Difficult. Journal of Management Policy and Practice, 16(4), 88.

- ar Jassim, J. and Khawar, M. (2018). Defining micro, very small & small enterprises: moving towards a standard definition-continuum. Continuum (34)

- Askool, S. and Nakata, K. (2010). A conceptual model for acceptance of social CRM systems based on a scoping study. Ai & Society, 26 (3), 205-220.

- Athanasoulias, G. and Chountalas, P. (2017). Managing Customer Relationships: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Future Directions. International Journal of Decision Sciences, Risk and Management, 7 (1/2), 70-87.

- Awiagah, R., Kang, J. and Lim, J.I. (2016). Factors affecting e-commerce adoption among SMEs in Ghana. Information Development, 32(4), 815-836.

- Ayandibu, A.O. and Houghton, J. (2017). External forces affecting small businesses in South Africa: A case study. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR), 11, 49-64. Available: http://jbrmr.com/admin/content/pdf/i-26_c-256.pdf (Accessed Accessed 1 June 2017).

- Azevedo, A.T.d. (2013). Customer relationship management adoption: determinants of CRM adoption by firms (Doctoral dissertation).

- Bahri-Ammari, N. and Nusair, K. (2015). Key factors for a successful implementation of a customer relationship management technology in the Tunisian hotel sector. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 6(3), 271-287. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-08-2014-0042 (Accessed Accessed 15 June 2017).

- Berisha, G. and Pula, J.S. (2015). Defining Small and Medium Enterprises: a critical review. Academic Journal of Business, Administration, Law and Social Sciences, 1(1), 17-28.

- Bharati, P. and Chaudhury, A. (2015). SMEs and competitiveness: The role of information systems. Bharati, P. and Chaudhury, A.(2009),“SMEs and Competitiveness: The Role of Information Systems”, International Journal of E-Business Research, 5(1)

- Blair, E. (2015). A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 6 (1), 14-29.

- Bradley, M.T. and Brand, A. (2016). Accuracy when inferential statistics are used as measurement tools. BMC Research Notes, 9(1), 1-3.

- Bruwer, J.-P. 2017. The conduciveness of the South African economic environment and small, medium and micro enterprise sustainability.

- Bruwer, J.P., Coetzee, P. and Meiring, J. (2018). Can internal control activities and managerial conduct influence business sustainability? A South African SMME perspective. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

- Bujang, M.A., Omar, E.D. and Baharum, N.A. (2018). A review on sample size determination for Cronbach’s alpha test: a simple guide for researchers. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences: MJMS, 25(6), 85.

- Cant, M.C. and Rabie, C. (2018). Township SMME sustainability: a South African Perspective. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, 14(7)

- Chaudhry, N.I., Aftab, I., Arif, Z., Tariq, U. and Roomi, M.A. (2019). Impact of customer-oriented strategy on financial performance with mediating role of HRM and innovation capability. Personnel Review, 48(3), 631-643.

- Chen, I.J. and Popovich, K. (2003). Understanding customer relationship management (CRM) People, process and technology. Business process management journal, 9(5), 672-688.

- Chiu, C.Y., Chen, S. and Chen, C.L. (2017). An integrated perspective of TOE framework and innovation diffusion in broadband mobile applications adoption by enterprises. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences (IJMESS), 6(1), 14-39.

- Conner, B. (2017). Descriptive statistics. American Nurse Today, 12(11), 52-55.

- Consonni, D. and Bertazzi, P.A. (2017). Health significance and statistical uncertainty. The value of P-value. Med Lav, 108 (5), 327-331.

- Creswell, J.W. and Creswell, J.D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Creswell, J.W. and Poth, C.N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

- Cruz-Jesus, F., Pinheiro, A. and Oliveira, T. (2019). Understanding CRM adoption stages: empirical analysis building on the TOE framework. Computers in Industry, 109, 1-13.

- Dalitso, K. and Peter, Q. (2000). The policy environment for promoting small and medium-sized enterprises in Ghana and Malawi. University of Manchester,

- Damayanti, Warsito, Meilinda, Manurung, P. and Sembiring, S. (2019). E-crm information system for Tapis Lampung SMEs. Journal of Physics, 1-12.

- Dawson, D.C. (2007). A Practical Guid to research method. Spring Hill House, Oxford: How To Books. Desai, V. and Potter, R.. Doing development research. London: Sage.

- DTI. (1996). National Small Business Act of 1996. President's Office. Available: http://www.dti.gov.za/sme_development/docs/act.pdf (Accessed 02 October 2019).

- Dubey, N.K. and Sangle, P. (2019). Customer perception of CRM implementation in banking context. Journal of Advances in Management Research,

- Elbeltagi, I., Kempen, T. and Garcia, E. (2014). Pareto-principle application in non-IT supported CRM processes: A case study of a Dutch manufacturing SME. Business Process Management Journal, 20(1), 129-150. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-05-2012-0043 (Accessed Accessed 12 July 2019).

- Fatoki, O. (2014). The causes of the failure of new small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20): 922.

- Fjermestad, J. and Romano, N.C. (2003). Electronic customer relationship management. Business Process Management Journal,

- Galvão, M.B., de Carvalho, R.C., de Oliveira, L.A. B. and de Medeiros, D.D. (2018a). Customer loyalty approach based on CRM for SMEs. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing.

- Galvão, M.B., de Carvalho, R.C., Oliveira, L.A.B.d. and Medeiros, D.D.d. (2018b). Customer loyalty approach based on CRM for SMEs. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(5), 706-716.

- Garcia, I., Pacheco, C. and Martinez, A. (2012). Identifying critical success factors for adopting CRM in small: A framework for small and medium enterprises. In: Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications 2012. Springer, 1-15.

- Gibbs, B.G., Shafer, K. and Miles, A. (2017). Inferential statistics and the use of administrative data in US educational research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 40 (2), 214-220.

- Gono, S., Harindranath, G. and Özcan, G.B. (2016). The adoption and impact of ICT in South African SMEs. Strategic Change, 25 (6), 717-734.

- Gonsalves, M. and Rogerson, J.M. (2019). Business incubators and green technology. Urbani Izziv, 30: 212-224.

- Gopaul, R. (2019). An assessment of strategic decision-making processes in small and micro enterprises in the services sector in South Africa. DUT.

- Guzmán, J.B. and Lussier, R.N. (2015). Success factors for small businesses in Guanajuato, Mexico.

- International Journal of Business and Social Science, 6(11), 1-7. Available: https://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_6_No_11_November_2015/1.pdf (Accessed 26 September 2016).

- Hasani, T., Bojei, J. and Dehghantanha, A. (2017). Investigating the antecedents to the adoption of SCRM technologies by start-up companies. Telematics and Informatics, 34 (5): 655-675.

- Hassan, S. H., Mohamed Haniba, N.M. and Ahmad, N.H. (2019). Social customer relationship management (s- CRM) among small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 35 (2), 284-302.

- Hendrayati, H. and Syahidah, R.K. (2018). Barriers and possibilities of implementation of customer relationship management on small and Medium enterprises by womenpreneurs. Jurnal Bisnis dan Manajemen, 19 (2), 72-87.

- Israel, G.D. (1992). Determining sample size. University of Florida, IFAS Extension,

- Jere, M., Jere, A. and Aspeling, J. (2015). A study of small, medium, and micro-sized enterprise (smme) business owner and stakeholder perceptions of barriers and enablers in the South African retail sector. Journal of Governance and Regulation.

- Josiah, U.J. and Nkamare, S.E. (2019). Effect of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) on the Performance of SMES on Hospitality Industry in Cross River State. International Journal of Marketing and Communication Studies 4(2), 17-26.

- Junkala, T. (2017). Customer Relationship Management in Finnish Ice-hockey League organizations.

- Kachlami, H. and Yazdanfar, D. (2016). Determinants of SME growth: The influence of financing pattern. An empirical study based on Swedish data. Management Research Review, 39 (9), 966-986.

- Khedhaouria, A., Gurau, C. and Torrès, O. (2015). Creativity, self-efficacy, and small-firm performance: the mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Small Business Economics, 44 (3): 485-504.

- Kothari, C. (2017). research methodology methods and techniques by CR Kothari. Published by New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers, 91

- Kunene, L.N. (2014). Brand naming strategies for SMME's in Ethekwini Municipality. Master in Commerce, University of KwaZulu Natal.

- Leboea, S.T. (2017). The factors influencing SME failure in South Africa. University of Cape Town.

- Lekhanya, L.M. (2015). Public outlook on small and medium enterprises as a strategic tool for economic growth and job creation in South Africa. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 4(4), 412-418. Available: https://ir.dut.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10321/1419/Extract%20Pages%20From%20JGR_%28Volume_4_I ssue_4_2015_Continued3%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed 1 June 2017).

- Lekhanya, L.M. (2016). Determinants of survival and growth of small and medium enterprises in rural KwaZulu–Natal. Doctor of Philosophy, University of the Western Cape. Available: http://etd.uwc.ac.za/handle/11394/5569 (Accessed 26 September 2019).

- Majama, N.S. and Magang, T. I.T. (2017). Strategic planning in small and medium enterprises (SMEs): A case study of Botswana SMEs. Journal of Management and Strategy, 8 (1), 74-103.

- Marczyk, G., DeMatteo, D. and Festinger, D. (2005). Essentials of research design and methodology. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Markwei, U. and Tetteh, P. M. (2020). Unpacking the ethics of access and safety of participants and researchers of child sexual abuse in Ghana. Children's Geographies: 1-11.

- Marolt, M. (2018). Social CRM Adoption and Its Influence on Customer Relationship Performance-SMEs Perspective. Univerza v Mariboru (Slovenia).

- Maziriri, E.T. and Chivandi, A. (2020). Modelling key predictors that stimulate the entrepreneurial performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and poverty reduction: Perspectives from SME managers in an emerging economy. Acta Commercii, 20 (1), 1-15.

- Meyliana, M., Sablan, B., Hidayanto, A.N. and Budiardjo, E.K. (2017). The critical success factors (CSFs) of social CRM implementation in higher education. In: Proceedings of. 2017. Available: http://dut.summon.serialssolutions.com/2.0.0/link/0/eLvHCXMwtV3Pb9MwFLZaTkgcQAxt (Accessed 27 November 2019).

- Miles, K.J. (2013). Exploring factors required for small business success in the 21st century. Walden University.

- Ministry of Small Business Development. (2015). Development national small business policy colloquium 2014.

- Speech by Minister of Small Business Development in the Opening Session of The National Small Business Policy Colloquium 2014. Sandton: Department of Small Business. Available: http://www.gpwonline.co.za/ (Accessed 10 January 2019).

- Muriithi, S. (2017). African small and medium enterprises (SMEs) contributions, challenges and solutions. Nag, D. and Das, N. 2014. A Framework for the Development and Success of Microenterprises in India. IUP. Journal of Business Strategy, 11 (3)

- Neuman, W. L. (2014). Basics of social research. Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

- Nguyen, T.H. and Waring, T.S. (2013). The adoption of customer relationship management (CRM) technology in SMEs: An empirical study. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20 (4), 824-848.

- Onyenego, O.L. (2018). Small Business Owners' Strategies for Success.

- Osano, H.M. (2019). Global expansion of SMEs: role of global market strategy for Kenyan SMEs. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 8 (1), 1-31.

- Page, J. and Shimeles, A. (2015). Aid, employment and poverty reduction in Africa. African Development Review, 27 (S1): 17-30.

- Paraschou, K. (2016). A strategic framework for the optimization of customer relationship management in SMEs. Patole, R. 2019. How does using Salesforce CRM affect the customer satisfaction in Indian SMEs. Dublin Business School.

- Payne, A. and Frow, P. (2006). Customer relationship management: from strategy to implementation. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(1-2): 135-168. Available: https://doi.org/10.1362/026725706776022272 (Accessed 27 November 2019).

- Pedron, C.D., Picoto, W.N., Dhillon, G. and Caldeira, M. (2016). Value-focused objectives for CRM system adoption. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116 (3): 526-545.

- Peter, F., Adegbuyi, O., Olokundun, M., Peter, A.O., Amaihian, A.B. and Ibidunni, A.S. (2018). Government financial support and financial performance of SMEs. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 17

- Pohludka, M. and Štverková, H. (2019). The Best Practice of CRM Implementation for Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Administrative Sciences, 9 (1)

- Pratt, A. and Virani, T.E. (2015). The creative SME: a cautionary tale.

- Puklavec, B., Oliveira, T. and Popovic, A. (2018). Understanding the determinants of business intelligence system adoption stages: An empirical study of SMEs. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118 (1): 236- 261.

- Rahimi, I. (2005). A critical success factor model for CRM implementation. The University of Manchester (United Kingdom).

- Rahimi, R. (2017a.) Customer relationship management (people, process and technology) and organisational culture in hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management,

- Rahimi, R. (2017b). Customer relationship management (people, process and technology) and organisational culture in hotels: Which traits matter? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29 (5): 1380-1402.

- Rahimi, R. and Gunlu, E. (2016). Implementing customer relationship management (CRM) in hotel industry from organizational culture perspective: Case of a chain hotel in the UK. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(1): 89-112. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04- 2014-0176 (Accessed 1 June 2017).

- Republic of South Africa. Development, S.B. (2019). Revised Shedule 1 of the National Definition of Small Enterprise in South Africa. 42304. Pretoria: Available: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201903/423041gon (Accessed 10 January 2020).

- Rigby, D.K., Reichheld, F.F. and Schefter, P. (2002). Avoid the four perils of CRM. Harvard business review, 80 (2), 101-109.

- Rigo, G.E., Pedron, C.D., Caldeira, M. and Araújo, CC.S.d. (2016). CRM adoption in a higher education institution. JISTEM-Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management, 13 (1), 45-60.

- Roopchund, R. 2019. Exploring Social CRM for development of SMEs in Mauritius. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 27 (01), 93-109.

- Sablan, B., Hidayanto, A.N. and Budiardjo, E.K. (2017). The critical success factors (CSFs) of social CRM implementation in higher education. In: Proceedings of 2017 International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS). IEEE, 1-6.

- Salah, O.H., Yusof, Z.M. and Mohamed, H. (2019). The Adoption of CRM Initiative among Palestinian Enterprises: A Proposed Framework. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management, 14, 367-403.

- Saleem, Q. (2013). Overcoming Constraints to SME Development in MENA Countries and Enhancing Access to Finance: International Finance Corporation. Available: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/581841491392213535/pdf/113701-WP-Overcoming- constraints-IFC-Report-PUBLIC.pdf (Accessed 20 September 2019).

- Schmidt, J., Bruwer, J.P., Aspeling, J. and Mason, R. (2016). Financing for SMME start-ups, and expansion for established SMMEs, in the retail sector. Wholesale and Retail SETA and CPUT.

- SEDA. (2016). The small, medium and micro enterprise sector of South Africa. Available: http://www.seda.org.za/publications/publications/the%20small,%20medium%20and%20micro%20ente rprise%20sector%20of%20south%20africa%20commissioned%20by%20seda (Accessed 10 October 2020).

- SEDA. (2020). SMME Quarterly Update-3rd Quarter 2019. Pretoria: Available: www.seda.org.za (Accessed 10 August 2020).

- Sharma, N. (2018). Management of Innovation in Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). In: Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Springer, 611-626.

- Simpson, S.H. (2015). Creating a data analysis plan: What to consider when choosing statistics for a study. The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, 68 (4), 311.

- Snyder, L. (2016). Confidentiality and Anonymity: Promises and Practices. In: Walking the Tightrope. University of Toronto Press, 70-78.

- Soni, P., Cowden, R. and Karodia, A.M. (2015). Investigating the characteristics and challenges of SMMEs in the Ethekwini Metropolitan Municipality. Nigerian Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 62 (2469), 1-79.

- Sota, S., Chaudhry, H., Chamaria, A. and Chauhan, A. (2018). Customer relationship management research from 2007 to 2016: An academic literature review. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 17(4), 277-291. Available: 10.1080/15332667.2018.1440148 (Accessed 27 November 2019).

- Stankovska, I., Josimovski, S. and Edwards, C. (2016). Digital channels diminish SME barriers: the case of the UK. Economic research-Ekonomska istra?ivanja, 29 (1): 217-232.

- Starzyczná, H., Pellešová, P. and Stoklasa, M. (2017). The Comparison of Customer Relationship Management (Crm) in Czech Small and Medium Enterprises According to Selected Characteristics in the Years 2015, 2010 and 2005. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 65 (5): 1767-1777.

- Subedi, B.P. (2016). Using Likert type data in social science research: Confusion, issues and challenges. International journal of contemporary applied sciences, 3 (2), 36-49.

- Sudhakar, S. (2015). Adoption of CRM Initiatives among the Small and Medium Enterprises-An Analysis of Factors and its Impact on Organizational Characteristics. Journal of Contemporary Research in Management, 10 (2): 79.

- Turner, D.P. and Houle, T.T. (2019). Conducting and reporting descriptive statistics. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 59 (3): 300-305.

- Venturini, W.T. and Benito, O.G. (2015). CRM software success: a proposed performance measurement scale. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(4), 856-875. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2014- 0401 (Accessed 12 June 2017).

- Wolter, J.S., Bock, D., Smith, J.S. and Cronin Jr, J.. (2017). Creating ultimate customer loyalty through loyalty conviction and customer-company identification. Journal of Retailing, 93 (4): 458-476.

- Worku, Z. (2013). Analysis of factors that affect the long-term survival of small businesses in Pretoria, South Africa. Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing, 1, 67-84. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jdaip.2013.1400 (Accessed 01 July 2017).