Original Articles: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

Exploring Entrepreneurs Exit Strategies in Indonesian Small And Medium-Sized Entreprises

Ayu Desi Indrawati, Udayana University

Ica Rika Candraningrat, Udayana University

I Gusti Bagus Honor Satrya, Udayana University

Abstract

Entrepreneurial exit strategy is a critical component in entrepreneurial process, where a well-prepared strategy helps entrepreneurs to reduce the potential loss of their current business, prepare them to face the post-exit era, and improve the chance of re-entering business after quitting. While such benefits might be true in the context of developed countries, we are critical of their existence in the context of less developed nations. We enrich the entrepreneurial process literature by examining entrepreneur’s exit strategy and the factors influencing it in the novel context of the South-East Asian - with a focus on Indonesia. We interviewed 21 Indonesians small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) entrepreneurs with diverse backgrounds, and our findings suggest a framework for entrepreneurial exit that constitutes four major strategies, which are resignation, asset sales, business sales, and succession. In addition, our research finds several models explaining how the entrepreneurs select each of these strategies.

Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) sector in Indonesia has been in a critical phase for the last five years. One of the indicators can be seen from the latest documents published by Indonesian Statistics Department (2014) who reported a contraction in SMEs’ production growth of minus 5.35 per cent in the fourth quarter (Q4) of 2013. Under this situation, certainly, Indonesian entrepreneurs have been facing difficulties in maintaining the company’s competitiveness and sustainability, and not a few of them have declared bankruptcy and exit from the market, or usually called as entrepreneurial exit (Collewaert, 2012; DeTienne, 2010). Without a good understanding of exit strategy and factors associated to it, entrepreneurs will struggle to organize their efforts to get back and start a new business, face difficulties to reorganize the resources they once have had, and have a big chance to repeat their failure experiences derived from the previous business (Dehlen, Zellweger, Kammerlander, & Halter, 2014; Hessels, Grilo, Thurik & Zwan, 2011; Wennberg, Wiklund, DeTienne & Cardon, 2010). Helping Indonesian entrepreneurs with the information about some practical exit strategy and the mechanisms behind the selection of exit strategy might be useful for them to reduce the negative impact of business failure. Yet, very little attention has been paid to the different methods Indonesian entrepreneurs use for exiting their company or what factors contribute to their choice of exit route, although it can be argued that designing an exit strategy would help not only the entrepreneur, but also the firm and national economies (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2014; Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014).

Entrepreneurial exit is defined as “the process by which the founders of privately held firms leave the firm they helped to create; thereby removing themselves, in varying degree, from the primary ownership and decision-making structure of the firm” (DeTienne, 2010, p. 204). This definition implies that the concept focuses on the individuals who exit from their business instead of on the firms who quit from the market. The research to date on entrepreneurial exit has found many factors that contribute to the selection of exit strategy, such as education level, work experience, understanding market experience, desire to pursue different interest, family reason, and emotional commitment to the firm (Cardon, Zietsma, Saparito, Matherne & Davis, 2005; Kammerlander, 2016; Parker, Storey & Van Witteloostuijn, 2010; Salvato, Chirico & Sharma, 2010). The main weakness of previous studies is that much of those studies have used big industry in developed countries as the context, while no studies have been identified to explore entrepreneurial exit strategy in the context of developing countries. Wennberg and DeTienne (2014) have sounded this note of caution and called researchers to react to these issues. Moreover, it is important to explore entrepreneurial exit concept in a new context, where there is a chance of finding a new exit strategy that is not only useful for the entrepreneurs itself but also for extending our understanding of exit strategy in the literature.

For these reasons, the present study addresses a fundamental research question regarding entrepreneurial exit in a developing country (i.e., Indonesia) setting: How do Indonesian entrepreneurs describe their decision and experiences to exit from the business? Using a qualitative approach, we answer this research question by identifying what entrepreneurs define by exit, what strategy is applied, and what motivations are behind the entrepreneurs to exit from their business. Our study contributes to the literature by providing new information about the exit strategy and the mechanisms through which the entrepreneurs select the specific exit strategy. This information might work as the cornerstone for the researchers who are interested to explore the entrepreneurial exit concept from relatively new perspective, and subsequently extend our insight about entrepreneurial exit.

We structure the paper as follows. First, we offer a brief description of entrepreneurial exit concept, followed by a discussion of the uniqueness and importance of entrepreneurial exit. Second, we elaborate on the current study’s methods, including those for the sampling strategies, the interview protocol, and the data analysis. Third, we elucidate our findings about entrepreneurs’ exit strategies and the factors influencing those strategies in the context of Indonesia. Finally, we propose an Indonesian model of entrepreneurs’ exit based on our findings and discuss how this model fit into and advance extant entrepreneurial exit literature.

Entrepreneurial Exit

There are many definitions of entrepreneurial exit in the literature. Hessels, Grilo, Thurik and Zwan (2011), for example, defined it straightforwardly as the act of “shutting down, discontinuing or quitting a business” (p. 448). Furthermore, Amaral, Baptista and Lima (2007), in explaining the meaning of exit, argued that the focus is not anymore in quitting, instead, the focus should be on whether it is a voluntary or involuntary decision. They continued, the term exit does not necessarily represent failure, because there is a case that the entrepreneurs leave their business when the performance deems to be sufficient. DeTienne (2010) offered a different perspective on the concept of exit. She argued that exit is about a process, a mechanism, through which the founders leave the firm completely. In this definition, she viewed exit as a broad concept, where there is a complex process works behind the screen before the entrepreneurs decide to leave the firm. Many scholars have then echoed this view and started to explore the factors that associated to the concept of entrepreneurial exit (Cefis & Marsili, 2011; Cumming, 2008; DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; Koçak, Morris, Buttar and Cifci, 2010; Mason & Harrison, 2006; Wennberg et al., 2011).

When reviewing the literature on entrepreneurial exit, there is evidence to indicate the maturity of the field. Wennberg et al. (2011), for example, argued that there are at least two strategies for executing the exit, which are sell the firm or pass it on to someone. Other scholars offered other strategies, such as liquidation, merger and acquisition, sale to a third party, employee buy-out, and a complete shutdown (Asterbo & Winter, 2012, DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; Ryan & Power, 2012). Focusing of the financial issue, Wennberg et al. (2010) argued that there is an interaction between sale factors (i.e., liquidation (or asset sale) and firm sale) and financial condition factors (i.e., financial distress and firms performing well). This interaction is proposed to result in four exit strategies, which are harvest sale, distress sale, liquidation, and distress liquidation. When understanding the process of exit strategy, scholars have argued the importance of understanding the exit intention of the entrepreneurs because exit intention is the first indicator to conclude whether the entrepreneurs decide to quit or stay in the business (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; Folta, Delmar & Wennberg, 2010). Others stated that there are divergent motives for entrepreneurs to leave the business they have, such as, for example, willingness to leave the firm, commitment to the firm, sales price expectations and personal or family reasons (Cardon et al., 2005; Kammerlander, 2016; Parker, Storey and Van Witteloostuijn, 2010; Ronstadt, 1986; Wennberg et al., 2010).

However, the abundant of research on the entrepreneurial exit still leaves a set of gaps for future research to fill. In their review paper of entrepreneurial exit, Wennberg and DeTienne (2014) argued that, although entrepreneurial exit is an old concept, there is still many unexplored outlet on the field of exit strategy, thus they call researchers to contribute in filling the gaps to extend our understanding of entrepreneurial exit. The role of intentions, investigation of the actual exit strategies of entrepreneurs, the focus on the process of exit, the use of qualitative work to explore the theory on exit, and the variations of country (or culturally) specific issue are the avenues that need to be further explored. Our work attempts to fill some of the gaps mentioned above.

Methods

Research Approach and Sample

The aim of our study is to enhance entrepreneurial process literature by answering the research question of how Indonesian entrepreneurs explain their experiences of quitting from current business, and the motivation or background behind this exit decision-making. This aim motivates us to conduct a qualitative study. We chose to study entrepreneurs in Indonesia, where the turnover rate of entrepreneurs (i.e., entrepreneurs who quit the business) is high but little evidence can be found about what exit strategy that Indonesian entrepreneurs actually use to leave the business. We sought to ensure a diverse sample to increase the validity of the interview data, and to match the fact that previous literature in the area has drawn data from various types of samples. We contacted the Department of Industry and Commerce of the Republic of Indonesia to obtain the data of SMEs and entrepreneurs who left their business recently. These data were then used as our basis to contact the entrepreneurs who had a willingness to participate in this study. We considered this approach as appropriate and necessary.

Data Collection and Interview Protocol

Four interviewers (i.e., all four authors) engaged in the data collection. All the interviews took place in dedicated and quite rooms, where one on one interviews were possible to be conducted. Interviews were conducted in Indonesian language (i.e., the mother tongue of all the entrepreneurs), lasted between 30 and 60 minutes, recorded with the participants’ permission, and transcribed verbatim within a week of the interviews.

Of the available qualitative research techniques, a semi-structured interviews technique was utilized. This technique helps the interviewers to ask participants a standard set of questions but was free to probe further on specific topics to get richer, more in-depth insight into the experiences of the informant. During the data collection process, the interviewers frequently discussed the data collection situation, analyzed the data tentatively, tweaked the interview questions when necessary, and tried to find solution if problems occurred (e.g., one participant had to quit the interview due to family matters). We relied on the concept of ‘saturation’ to decide the finish line of the data collection process (Creswell, 2009). Given that the purpose of this study is to explore informants’ experience about exit, their strategies to exit, and the background of the strategy selection, we did not provide any definition of “entrepreneurial exit strategy” to the participants.

The interview protocol was then developed, which contains two major parts. First part was set to explore a general picture of participants, their demographics, and their current environmental aspects that were meaningful to them and the interview. We asked an initial question: “What do you do after you quit your business?” Afterward, we explored further this question by asking several following questions: “What is your last business before the current one?” “When did you start the previous business?” “How long have you run the previous business?” “When did you quit from that business?” Once we obtained their responses to these questions, we then proceeded to the second part, where we grasped many aspects of participants’ background or motivations to leave their previous business. We asked questions such as, “What made you quit?” “What happened?” “Who provoked you to quit from the business?” “Could you tell me the story?” “How did you feel?” and “How did you quit from that business?” This approach helped participants cite concrete and specific situations that would help us understand the motivation or background behind their exit, while at the same time exploring their chosen exit strategy. In the final part of the protocol, we sought to help participants found their definition of entrepreneurial exit and its strategy. We asked, “What does ‘exit’ mean to you?” Typically, participants defined exit to leave the business, and mentioned many ways of exit. We then further probed the topic: “Could you further explain about those ways?” “Could you define those ways as ‘strategic options to exit’?” Finally, we asked the participants: “From those several ways, which ways that you think you choose to exit?” The final question helped us characterize and label one of the four identified exit strategies.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed by exploring themes that represented the chosen exit strategy and the factors (or motivation) that influenced the selection of that specific exit strategy. We followed Miles and Huberman’s (1994) four stages of qualitative methodology, which were data collection; data reduction; data display; and conclusion drawing/verification. Regarding data reduction and transformation of the raw interview transcripts into an analyzable form, the interview transcripts were reviewed several times and then a tally sheet was adapted to summarize the number of times a word, phrase, or statement was mentioned in each interview. In the data display stage, we did three sub-stages to answer our research question. First sub-stage was coding, where we tried to isolate those words, phrases and statements that were important for answering our research question. Afterward, in the second sub-stage, we categorized those words or phrases that carry a same meaning under one label or category. The final sub-stage had us exploring whether there was some relationship found between each category to understand the general picture.

In the conclusion drawing/verification stage the focus was on the validity and reliability of the results. In terms of validity, we used three qualitative validity approaches to ensure the data validity: (1) data triangulation; (2) rechecking participants’ transcript; and (3) involve external auditor (Creswell & Miller, 2000). We ensured that the interviews have been conducted on several resources to ensure that the data has been collected from multiple perspectives. Related to participants’ data rechecking, this study has sent the transcript back to the participants, so the participants could verify what has been said, what has been written, and what meaning each statement has conveyed. Lastly, we used one expert in management field (with Ph.D. qualification and is not related to this study) to assess the accuracy of interpretation of the qualitative data. This expert has confirmed that the conclusion drawn from this study has its logic and structure.

Qualitative data reliability is defined as the extent to which the researchers hold his consistency across the participants during several interviews (Gibbs, 2007). To ensure the reliability of the qualitative data, interviewer must document the interview procedure as detail as possible (Yin, 2003). In this research, there are four procedures to ensure its reliability. First procedure is to ensure that the interview has been conducted in a quiet and separated single room, either in English or Indonesian, has been recorded under the participant permission, conducted by the researcher, and in the duration between 30 to 60 minutes. The second is that the interview results must be written or transcribed in one place, read for several times to minimize misinterpretation, and analyzed. Third, the interview results must be verified by the participants. The fourth procedure is that each of interview results must be written and reported to the principal researcher to be finalized. These procedures are the guidelines to ensure the data reliability of this study.

Findings

Our analysis of entrepreneurial exit strategies for Indonesian entrepreneurs who work in SMEs in Indonesia revealed that the entrepreneurs in Indonesia tend to leave their business through four distinct exit ways: resignation, asset sales, business sales, and succession. Furthermore, data analysis suggested that the dominant drivers for entrepreneurs to exit from their business were, for example, perceived unethical behaviors, own background, individual capabilities, and external support. It is notable, however, that there was a great deal of overlap between these drivers in influencing the exit strategies. In the sections that follow, we discuss each type of exit strategy in turn and then describe the factors or drivers that motivate the entrepreneurs to leave the business.

Exit Strategy 1: Resignation

Three entrepreneurs indicated that they had to accept the undesirable but inevitable condition that pushes them to give up and leave the current business. We called it “resignation strategy”. This strategy can be in an informal (i.e., stating verbally in an information condition) or formal (i.e., writing a statement to the business partner) form. For example, one entrepreneur in an exported-handicraft business stated:

“My dream to this business was too big. I wished I could make this [business] as my future, [i.e.,] the source of my passive income in the future, the place where my kids rely their life on. However, there were certain mistakes that you have done and you could not avoid during the process, the mistakes that pushed you into the [exit] door. At the end, I just simply gave up and move on.”

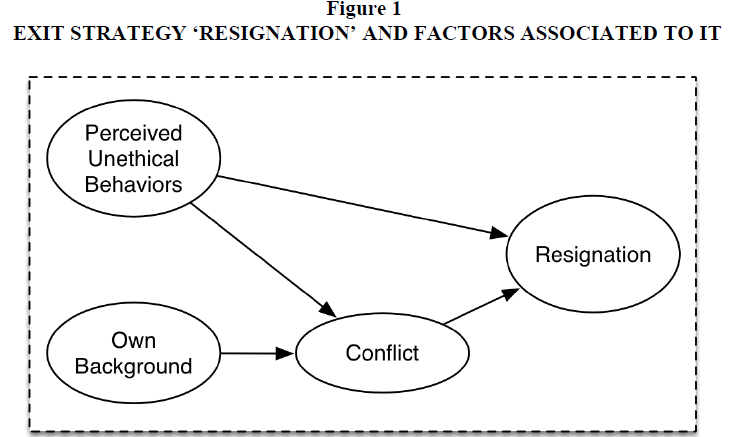

The selection of this strategy is motivated through three interconnected variables: (1) perceived unethical behaviors, (2) own background, and (3) conflict (see Figure 1). Perceived unethical behaviors were one of the factors that influenced entrepreneurs to resign from their business. Perceived unethical behavior was described as the extent to which the entrepreneurs perceive the behavior of their business partner as ethical. Several unethical behaviors that were mentioned in the interviews were unequal distribution of profit, unauthorized intervention to some activities, intention to dominate the business, and financial fraud. Another factor is called “own background”, which refers to the entrepreneur’s internal activities or situation that are not related to the business but apparently demotivate the entrepreneurs to continue their business. The obligation to complete the study degree, which happened on one entrepreneur who was still in a status of postgraduate student, and the feeling of being forced to run the business were two undesirable situations that entrepreneurs faced during the run of their business. As the postgraduate-student entrepreneur explained:

“I think, at that time, there was no chance that I could continue the business. On one side, the student life was so demanding. Abundant homework had to be completed in a week or two. On the other side, the business revenue was declining due to the lack of attention that I have put into the business. Then, at one time, there was a letter coming from the [administrative] office, asking me to submit the thesis proposal.”

Another factor that manifested from our data was conflict. Conflict could occur from the unethical behaviors of the business partner perceived by the entrepreneurs. For example, once the entrepreneurs felt cheated, he would conform or clarify the business issues directly to his partners. Unsatisfactory clarifications would tense the relationship between both, and subsequently could end the connection between these two partners. Alternatively, conflict could come from internal evaluation within the self, especially when the entrepreneurs had another responsibility to complete (e.g., running a business while developing a postgraduate thesis). Moreover, entrepreneurs who run a business against their wishes, or being forced to run a business might end up quitting their business before their business had a chance to flourish. These two factors (i.e., perceived unethical behaviors, and own background) could be the source of conflict, which subsequently motivated the entrepreneur to resign from the business they had. To illustrate:

“The situation became tense. I showed him our cash flow report and directly pointed at the trend that I thought was not usual. He tried to clarify, but the more he spoke the more my trust declined. I also reminded him his action when he spoke to the supplier behind my back; this was once approached by me. I could not accept such behaviors. I said that I could not stay in this situation any longer.”

From another interview, one entrepreneur who ran a retail business noted:

“Going back years ago, that [business] was not what I wanted. I graduated as an engineer but I ended up worked as a retailer. Deep inside, if I can be honest, I was crying but at that time, really, I did not have any options. I carried this burden for years before I finally pushed myself to be on track, matching my competence and be a real engineer.”

Exit Strategy 2: Asset Sales

The second exit strategy is called ‘asset sales’. Seven participants consistently reported that selling the asset was difficult, especially when they faced a global financial crisis at that time. However, they stated that it was an easier way to exit because they would not experience many losses, especially if they had intention to jump to another type of business that did not need any of their current resources or assets. Illustrating views about the selection of ‘asset sales’ as their exit way is the following quote from an entrepreneur who runs a culinary business:

“Time was up. The revenue was showing a stagnancy trend and no chance to grow. As the one who initiated the business, I then offered my partner to sell what we had in store, and use the money to start a new life, in a new market. Finding the buyers was the tricky task one, but that was our only choice I believe.”

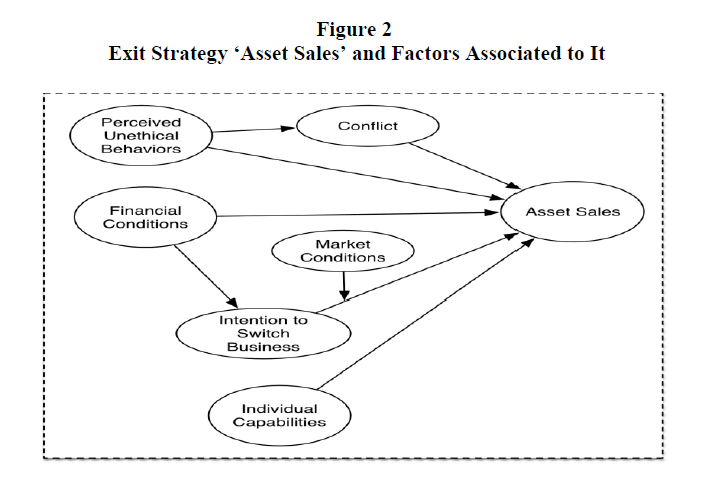

Data analysis suggested that there were at least three mechanisms through which the entrepreneurs chose to sell their asset as their exit way (see Figure 2). The first mechanism was about the interaction between the business’ financial conditions, entrepreneurs’ intention to switch business, and the market condition. The financial condition represented the profit, cash flow, income statement, and the debt level that the organization recorded to date. This became the primary condition that motivated the entrepreneurs to leave the business. Entrepreneurs would use its current financial condition to think whether the business they ran worth to be continued. If the answer was no, then at this exact point entrepreneurs had in their mind the intention to jump to another type of business and quit from their own business. However, whether this intention would be translated into action (i.e., exit the business) depended on how the market situation at that time. If the price of the assets were perceived as acceptable, then the entrepreneurs might proceed into the exit door. The following comments by a participant exemplify this situation:

“I saw other business opportunities, and apparently the second hand price for my machinery and tools was very good so I sold all my resources and started identifying what I would do next. If it would have been in a different situation [i.e., bad price for the assets], then I would not sell it and I might probably be still in the business.”

The second mechanism was the same with the mechanism that motivated entrepreneurs to simply resign from their business, which are the relationship between perceived unethical behaviors, conflict that was raised because of this unethical perception, and exit strategy. Some entrepreneurs who chose to sell the assets were also faced by the condition that their business partner was not truly truthful. The only difference between the entrepreneurs who quitted through the ‘resignation’ door with the one who exited from the ‘asset sales’ door was that the latter held more authority to decide where they wanted to direct their business. For instance, after they found that they were being cheated, they confronted the partner. Subsequently, if they did not satisfy with the explanation, they might end their relationship, took their right to sell whatever resources they had in the organization, and leave the business.

The last mechanism related to individual capabilities. Individual capabilities, such as the capability to adapt with the business changes, the conceptual knowledge of managing and organizing, and creativity, influenced entrepreneurs to end their business through specific exit way (i.e., asset sales). Specifically, one entrepreneur stated:

“I might have the brevity of the entrepreneurs, I might have the original idea about what business should be run in what situation, but I did not have the level of understanding about managing the relationship. I tell you what. One of my suppliers was always be good to me, but I understood that the price of goods they sold to me was quite higher than they sold to my friends. I tried to negotiate but failed. Before I lost to many, I sold all the equipment.”

Exit Strategy 3: Business Sales

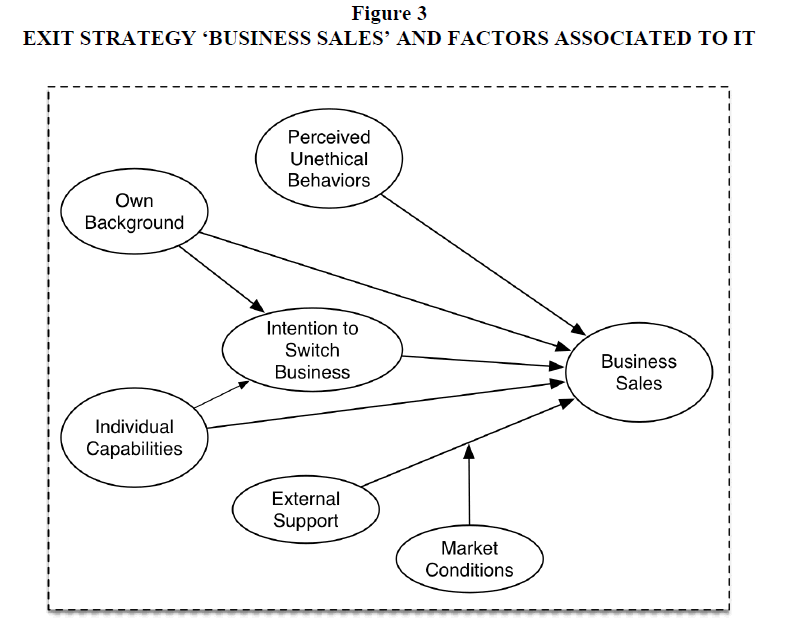

Selling the whole business, or ‘business sales’, was the third exit strategies that have been mentioned by six entrepreneurs who involved in this study. Instead liquefy the assets one by one to the market, entrepreneurs who chose this way would sell all the business they had in a package, including the resources, the business permit, the right to suppliers, and the distribution channel. From the interviews, it can be found that there were three mechanisms that could explain why the entrepreneurs sold their business (see Figure 3). First mechanism highlighted the role of entrepreneurs’ intention to switch business in mediating the relationship between the owner background or individual capabilities and exit through business sales. A feeling of bored or saturated with the business condition and seeing business opportunities in another market segment were two indicators of switching intention that was stimulated by either the feeling of being forced to run the business or entrepreneurs’ capabilities to run the business itself. For example, one entrepreneur in a studio recording business noted:

“I really did not have any interest to run it [the business] but my father asked me to do so. After several years in learning how to love it, I just could not find a way. My day-to-day activities became so mechanistic, in terms of coming to the office, control the staff, and got home. Once I had a full authority to run the business, I decided to sell it to my friend. The sales were quite good, and here I am now with the business that I love to run.”

The second mechanism suggested that the relationship between the perceived support from entrepreneurs’ entourage and market condition (e.g., investor who is willing to buy the business) was one of the key drivers in demotivating entrepreneurs’ spirit to run the business. A young female entrepreneur in the interviews stated that:

“I confess that I ran that business just to spend my spare time and also to make friends. As time goes by, I enjoyed it although the money I got was not equal with the effort I put into [the business]. Here comes the problem where I no longer had spare time and started collecting protest from my best friends because I was being too busy. I finally sold my business to one foreigner that was really looking to do his first investment here.”

Last mechanism involved one factor that apparently became one key driver to push the entrepreneurs to the exit door in many ways (e.g., resignation, asset sales, and business sales). This factor was the perceived unethical behavior. However, instead of being tricked by their business partner, the entrepreneurs found themselves being tricked by their employees. For example, one entrepreneur who ran the culinary business noted how he was being tricked by his staff:

“Fortunately it only involved small money . . . Once I found their tricks, I called it off, got them all fired, and, while waiting the appropriate time to run another business, sold that cafe.”

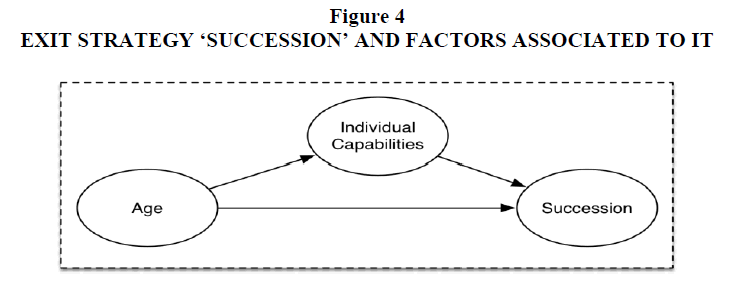

Exit Strategy 4: Succession

Succession was the last strategy that has been mentioned in interviews. In the entrepreneurial exit literature, succession was defined as the activities of giving the next individual or cadre in the rank, mostly the close family, the right to occupy the top management position or as an owner (Sharma, Chrisman and Chua, 2003). Five entrepreneurs stated that they used this strategy to ensure the continuity, stability, and sustainability of its business. Furthermore, from our interviews, we found that the succession strategy was mostly driven by age and its influence on the capability of entrepreneurs to manage the business (see Figure 4). For example, a senior businessman who has had several businesses ran at the same time discussed how he must start and prepare the next generation to be in charge in the business:

“I was not thinking to give this business to my son, because I thought I was still productive. However, age does not lie. I missed several important meetings with my retailer partners. I also lost pace with the technological issues that have played a big role in my business. And so, that was the time I decided to ask my kid to take care this freight. I believed he is ready.”

Discussion

The main objective of this study is to extend the literature of entrepreneurial exit by exploring the types of exit strategy that have been used by entrepreneurs and the factors associated with it from a novel context, which is Indonesia. Although several studies on the field of entrepreneurial exit has identified several exit strategies and its drivers, but the studies have been limited to developed countries. To date, there has not been a thorough investigation of how entrepreneurs in the context of developing countries, such as Indonesia, select their exit strategy when they decide to leave the business. Our study attempts to cover this issue by identifying a general model of exit strategy that Indonesian entrepreneurs usually use using a qualitative approach. We have found four exit strategies that Indonesian use to quit from their business, and several mechanisms that can explain why some entrepreneurs choose a specific exit strategy. In the following sections, we discuss about an Indonesian model of entrepreneur’s exit strategy, and explain how this model adds to the current entrepreneurial exit literature. The limitations of this study and agenda for future research will also be explained.

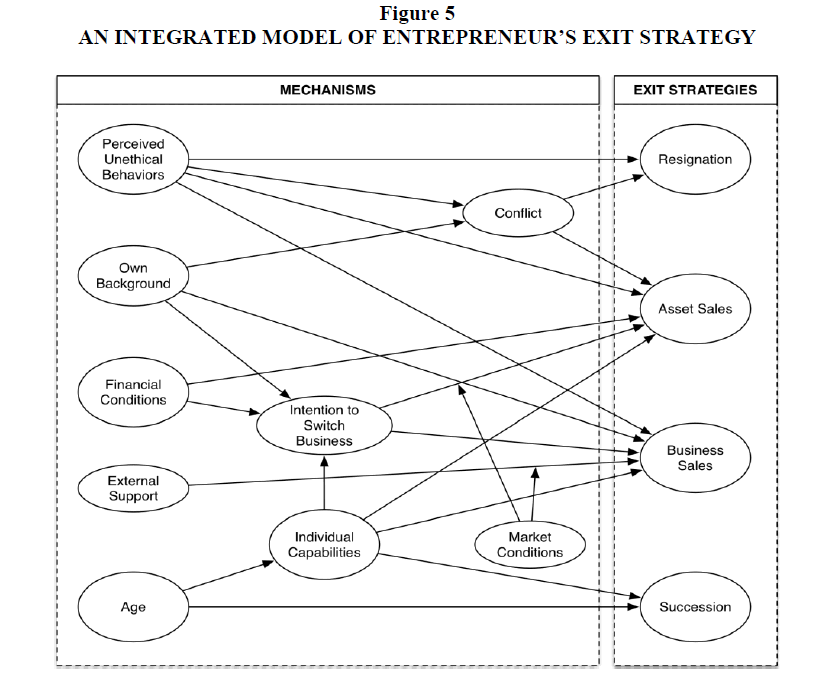

An Integrated Model of Entrepreneur’s Exit Strategy

Figure 5 clarifies an integrated model of entrepreneur’s exit strategy that is developed from the context of Indonesia. This model is developed based on the integration of four models of exit strategy that have been shown in the findings section (see Figure 1 to Figure 4). We are hopeful that this model may provide a big picture about the strategies of exit of Indonesian entrepreneurs and the factors influencing individuals’ selection out of business ownership.

We summarize three points to elucidate the model that we have developed in this study. These points are argued to be the theoretical contributions of this study to the literature. First point relates to the modes of the exit (i.e., exit strategies), where we find that there is at least four exit strategies that Indonesian entrepreneurs usually use when they decide to leave the business. These four exit strategies are resignation, asset sales, business sales and succession. This finding is in line with several studies focus on the field of entrepreneurial exit. Many scholars, for example, have pointed out that succession is one of the famous exit strategies chosen by the owner of the family firm (DeMassis, Chua & Chrisman, 2008; DeTienne & Cardon, 2010; DeTienne & Chirico, 2013; Nordqvist, Wennberg, Bau & Hellerstedt, 2013; Steier, Chrisman & Chua, 2004). Family succession is defined as the process through which the owners of a family firm transfer not only the ownership of the firm, but also the rights and obligations to manage the firm continuity and care of the firm and the employees to other family members (Sharma et al., 2003). In our study, most entrepreneurs who run family-type firms have chosen succession as their exit strategy due to having the advantage of family and organization culture transfer, willingness to put the family interests above all, and having high truthfulness to the successors.

Regarding sales, we find that there are two types of sales to be used as an exit strategy:

(1) Asset sales (2) business sales. This supports the conceptual model proposed by Wennberg et al. (2010), but has not yet been tested in an empirical context. Using expected utility and prospect theories on entrepreneurial exit, they argue that there might be two exit routes for entrepreneurs, which are through liquidation (or in our case, asset sales) and firm sale (which in our case called business sales). These two works might work under two conditions: (1) firms in financial distress; and (2) firms performing well. The interaction between the conditions and routes results in four distinct exit strategies, which are harvest sale, distress sale, liquidation, and distress liquidation. In our study, financial distress becomes key factor that motivates entrepreneurs to liquefy their assets or sell the firm, either directly or indirectly through entrepreneurs’ intention to switch business. However, we argue that financial conditions are not the only factor. Some entrepreneurs stated that they did not aware of the financial state of the firms, but if they found themselves being cheated, especially from their business partners (i.e., perceived unethical behaviors), they would like to consider quitting from the business through financial liquidation or firm sale. This type of behaviors has not yet been explored as the one of the factors that influences exit.

One exit strategy has occurred from our qualitative data, which has not yet been explored in the literature. We call it as resignation strategy. In here, we define resignation as the act of voluntary giving up to the undesirable business situation, where entrepreneurs face no options except resign from the ownership of the business. It can be planned at the beginning of the entrepreneurial process (i.e., proactive) by setting up a threshold situation as the basis of exit, or it can be a reactive action that entrepreneurs show to survive from the big loss they might have faced.

Second point that can be derived from our integrated model is that there are nine identified factors that are in some way associated with the four exit strategies we found in the Indonesian context. First factor is perceived unethical behaviors. These behaviors are represented by, for example, the intention to take over or to have a full authority of the business, financial fraud, and inappropriate interventions by the business partner. Second factor is own background, which indicates by the obligation to complete other equal responsibilities and the feeling of being forced to run the business. Third factor is the financial conditions, which represents the cash flow conditions, profit conditions, and the condition of income statements. Fourth is about the external support that entrepreneurs have when they run the business. Fifth factor that influences exit is conflict, and sixth is intention to switch to other type of businesses. The next two factors that influence the selection of exit strategies are related to the individual characteristics of the entrepreneurs, which are individual capabilities (e.g., the capabilities to adapt quickly to the business changes, the skills of managing and organizing firms, creativity) and demographic factors, such as age. Last, we found market conditions (e.g., competition level, price of the products or assets) as the key factor that strengthen or weaken entrepreneurs’ decision to exit.

Third point that we offer from our study is about the explanation of mechanisms through which the entrepreneurs choose the exit strategies that are available to them. All nine factors explain above are to some extent related to each other before they drive entrepreneurs to the exit modes. We find that five factors act as the first stimulant that is sufficient to entrepreneurs to think about leaving their business. These factors are perceived unethical behaviors, own background, financial conditions, external support, and age. These factors, however, could also indirectly influence the selection of exit strategies through three mediators, which are entrepreneurs’ intention to switch business, individual capabilities, and conflict. For example, the unethical behaviors shown to the entrepreneurs could ignite the existence of conflict between the owners, which subsequently enhance entrepreneurs’ intention to quit from the business. Previous studies have explained the relationship between perceived unethical behaviors and conflict (please see Collewaert & Fassin’s (2013) or Korsgaard, Jeong, Mahony and Pitariu’s (2008) studies), however, the action of exit as the outcome of conflict has not much been explored in the literature. Our work attempts to extend this shortage.

Another mechanism that has not yet been explored in the literature is the interaction between financial conditions, intention to switch business, and business sales. Although Wennberg et al. (2010) have pointed out that financial conditions might be the key drivers behind entrepreneurs’ exit decision they have not specifically come to the issue of behavioral intention of entrepreneurs after facing bad financial conditions. Our data shows that when entrepreneurs have faced financial distress, their first intention is not to quit the business, but to switch business. It implies that entrepreneurs might still be in their current business (i.e., not exiting the business) but create another business. This finding extends the literature on the field of entrepreneurial exit. Furthermore, based on the model, it is also argued that demographic factors such as age can influence exit strategies, either directly (e.g., succession exit strategy) or indirectly (e.g., business and asset sales) through entrepreneurs’ capabilities, their intention to switch business, and the current market conditions. These mechanisms are expected to be one of the bases to answer many questions about the factors that associated to entrepreneurs’ action of leaving the business through specific exit door, especially from the context of developing countries.

Limitations and Future Research

Although our study possesses several contributions to the literature, there are several limitations that should be noted. First, given our purpose and the nature of the variables that we examined, we only assume one type of entrepreneur. There are, however, many types of entrepreneur. Hessels et al. (2011) argued that there are at least five types of entrepreneur that are involved in the entrepreneurial process or entrepreneurship: potential, intentional, nascent, young, and established. Certainly, this assumption would limit our analysis regarding what type of entrepreneurs select what exit strategies, when and in what mechanisms. Future studies might consider testing this model to different type of entrepreneurs to understand which strategies are still available for the entrepreneurs, and what mechanisms that still works or does not works for specific types of entrepreneur.

Second, we also acknowledge that whether our findings are replicable in other developing countries or industries is an empirical question. This is due to the contextual strategy of this study, where this study only explored the issue of exit strategy in one developing country (i.e., Indonesia), using small-and-medium enterprises (SMEs) as the context. We supportively encourage future researchers to apply qualitative approach to explore other modes of exit strategy in other developing countries and all scales of business. Third, the model in Figure 5 has been developed inductively from the perspectives of entrepreneurs. Certainly, from the managerial point of view, we must be careful when we attempt to explain the exit strategy of entrepreneurs in other countries using this model due to the cultural difference that is exist in the different context. Therefore, we urge researchers to develop psychometrically sound measures for the variables involved in the model, test critical theoretical questions regarding the validity of the model, and quantitatively test the model in different context to achieve high generalization of the model. In a nutshell, future research should consider covering the limitations raised in this study to fully understand the phenomenon of entrepreneurial exit.

References

- Amaral, A.M., Baptista, R. & F. Lima (2007). Entrepreneurial exit and firm performance. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 27(5), 1-15.

- ┼sterbo, T. & J.K. Winter (2012). More than a dummy: The probability of failure, survival and acquisition of firms in financial distress. European Management Review, 9(1), 1-17.

- Cardon, M.S., Zietsma, C., Saparito, P., Matherne, B.P. & Davis, C. (2005). A tale of passion: New insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood metaphor. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 23-45.

- Cefis, E. & Marsili, O. (2011). Revolving doors: Entrepreneurial survival and exit. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21(1), 367-372.

- Collewaert, V. (2012). Angel investors? and entrepreneurs? intentions to exit their ventures: A conflict perspective.

- Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 753-779.

- Collewaert, V. & Fassin, Y. (2013). Conflicts between entrepreneurs and investors: The impact of perceived unethical behavior. Small Business Economics: An Entrepreneurship Journal, 40(3), 635-649.

- Creswell, J.W. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (Third Edition).

- London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Cumming, D. (2008). Contracts and exit in venture capital finance. Review of Financial Studies, 21(5), 1948-1982.

- Dehlen, T., Zellweger, T., Kammerlander, T. & Halter, F. (2014). The role of information asymmetry in the choice of entrepreneurial exit routes. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 193-209.

- DeMassis, A., Chua, J.H. & Chrisman, J.J. (2008). Factors preventing intra-family succession. Family Business Review, 21(1), 183-199.

- DeTienne, D.R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203-215.

- DeTienne, D.R. & Cardon, M.S. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 352-374.

- DeTienne, D.R. & Chirico, F. (2013). Exit strategies in family firms: How socioemotional wealth drives the threshold of performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1297-1318.

- DeTienne, D.R. & Wennberg, K. (2014). Small business exit: Review of past research, theoretical considerations and suggestions for future research. In S. Newbert (Eds.), Small Businesses in a Global Economy: Creating and Managing Successful Organizations. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishing.

- Folta, T.B., Delmar, F. & Wennberg, K. (2010). Hybrid entrepreneurship. Management Science, 56(2), 253?269. Gibbs, G.R. (2007). Analyzing Qualitative Data (First Edition). London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Hessels, J., Grilo, I., Thurik, R. & Zwan, P.V.D. (2011). Entrepreneurial exit and entrepreneurial engagement. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21(3), 447-471.

- Indonesia Statistics Department (2014). Statistik Indonesia 2014. Downloaded from http://www.bps.go.id/index.php/publikasi/326.

- Kammerlander, N. (2016). ?I want this firm to be in good hands?: Emotional pricing of resigning entrepreneurs. International Small Business Journal, 34(2), 189-214.

- Košak, A., Morris, M.H., Buttar, G.M. & Cifci, S. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit and reentry: An exploratory study of Turkish entrepreneurs. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15(4), 439-459.

- Korsgaard, A., Jeong, S.S., Mahony, D., & Pitariu, A. (2008). A multilevel view of intragroup conflict. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1222?1252.

- Mason, C.M. & Harrison, R.T. (2006). After the exit: Acquisitions, entrepreneurial recycling and regional economic development. Regional Studies, 40(1), 55?73.

- Miles, M. & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis (First Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Nordqvist, M., Wennberg, K., Bau, M. & Hellerstedt, K. (2013). An entrepreneurial process perspective on succession in family firms. Small Business Economics: An Entrepreneurship Journal, 40(4), 1087?1122.

- Parker, S.C., Storey, D.J. & Van Witteloostuijn, A. (2010). What happens to gazelles? The importance of dynamic management strategy. Small Business Economics, 35(2) 203-226.

- Ronstadt, R. (1986). Exit, stage left: Why entrepreneurs end their entrepreneurial careers before retirement. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(3), 323-338.

- Ryan, G. & Power, B. (2012). Small business transfer decisions: What really matters? Evidence from Ireland and Scotland. Irish Journal of Management, 31(2), 99-125.

- Salvato, C., Chirico, F. & Sharma, P. (2010). A farewell to the business: Championing exit and continuity in entrepreneurial family firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 22(3-4), 321-348.

- Sharma, P., Chrisman, J.J. & Chua, J.H. (2003). Predictors of satisfaction with the succession process in family firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 667-687.

- Steier, L.P., Chrisman, J.J. & Chua, J.H. (2004). Entrepreneurial management and governance in family firms: An introduction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 295-303.

- Wennberg, K. & DeTienne, D.R. (2014). What do we really mean when we talk about ?exit?? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. International Small Business Journal, 32(1), 4-16.

- Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., DeTienne, D.R. & Cardon, M.S. (2010). Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: Divergent exit routes and their drivers. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(4), 361-375.

- Yin, R.K. (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (First Edition). California, US: Sage Publications.