Research Article: 2020 Vol: 23 Issue: 1S

Exploring Entrepreneurial Intentions in University Students in Chile: A Context Analysis

Jorge Jarpa V., Computer Engineering Department, Faculty of Science, Universidad Mayor, Manuel Montt 318, Providencia, Santiago, Chile

Christian Cancino, Department of Management Control and Information Systems, University of Chile, Diagonal Paraguay 257, Santiago, Chile

Katherine Alvarez Ruf, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universidad Andrés Bello, República 252, Santiago, Chile

Citation Information: Jarpa V.J., Cancino, C., & Alvarez Ruf, K. (2020). Exploring entrepreneurial intentions in university students in chile: A context analysis. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(6).

Abstract

The scientific literature has studied the entrepreneurial intention (EI) of university students analysing their personal characteristics, the ability to generate networks, leadership and risk propensity. Less has been studied regarding the contexts presented by universities to foster entrepreneurial abilities in their students. The aim of this study is to analyse the entrepreneurial context (EC) in universities and measure the EI of public versus private university students in Chile. To do this, a study with a new construct was applied to test a reliability analysis, considering five dimensions of entrepreneurial sub-contexts (ESC), taking 415 students as the sample from two recognized universities in Chile. The results show that entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial sub-contexts were statistically significant differences between public and private universities. Each entrepreneurial sub-context identified may contribute to create a favourable atmosphere to entrepreneurial intention. Since the university context may influence students to become an employees or entrepreneurs, universities can be seen as potential sources of future entrepreneurs. Finally, this study recommends universities consider each entrepreneurial sub-context identified, in order to improve students’ entrepreneurial intention in the next years of economy recovery after COVID-19.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Context, Entrepreneurial Intention, Entrepreneurship, Universities, Chile.

Introduction

There are several academic studies that analyze the entrepreneurial intention of university students. Different theories or visions are raised about the determining factors that would have an influence in showing a lesser or greater entrepreneurial spirit.

Not only theories of entrepreneurship have proposed that entrepreneurs are shaped by contextual influences (Kacperczyk, 2012), but also sociological theories of entrepreneurship have increasingly related entrepreneurship rates to contextual influences (Aldrich & Ruef, 2006; Thornton, 1999). A host of studies document the impact of universities’ structural and institutional attributes on entrepreneurial rates (Bercovitz & Feldman, 2008; Roberts, 1991; Shane, 2004; Stuart & Ding, 2006; Zucker et al., 1998). In these studies peers are thought to affect an individual’s decision to enter entrepreneurship by transmitting entrepreneurial values and shaping career aspirations and attitudes toward entrepreneurship (Giannetti & Simonov, 2009; Nanda & Sørensen, 2010; Stuart & Ding, 2006). Many studies claim that intermediate linkages (Wennekers & Thurik, 1999) or contextual factors (Zahra et al., 2014) play an important role in the transmission mechanism. Ványi et al., (2016) focus on educators’ role in entrepreneurship education. Research in the area of entrepreneurship has already established that some entrepreneurial characteristics influence entrepreneurial intention. However, few studies have investigated the university environment as a context for entrepreneurship (Bignotti & Le Roux, 2016; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015).

The current study aims to understand the perceptions of undergraduate students regarding the entrepreneurial context (EC) and entrepreneurial intention (EI). The objective is to analyze the entrepreneurial context in universities identifying different entrepreneurial sub-contexts and measure the entrepreneurial intention of public and private university students in Chile.

To achieve this objective, a study with a new construct was applied to test a reliability analysis, considering five dimensions of entrepreneurial sub-contexts (ESC), with a sample of 415 students from two universities, a public and a private one. While the public university is a recognized traditional university with an employment rate among graduates greater than 88%, the private university as a non-traditional university in Chile with an employment rate among graduates less than 80%. Our research methodology considers bivariate analysis as a statistical technique. Subsequently, applying Alpha Cronbach coefficients to the new construct proposal was consistent with high score in each dimension. Finally, using contingency tables and the Chi-Square test help us to identify relationships between two variables.

The results of this study show statistically significant differences of the entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial sub-contexts between two samples, public and private universities. Furthermore, entrepreneurial intention after graduation and up to five-year after graduation, and entrepreneurial sub-contexts influence on entrepreneurial intention showed statistically significant differences. Therefore, this research allows us to conclude that each entrepreneurial sub-context identified may help to create a favourable atmosphere to entrepreneurial intention. To promote entrepreneurship at educational institutions it is not only necessary reinforce entrepreneurial communication from university corporate and university academic department, but also train professors on entrepreneurship and consider influences from peer-to-peer communication and the labour market sub-context. Since the university context may influence students to become employees or entrepreneurs, universities can be seen as potential sources of future entrepreneurs.

The paper recommends that universities consider each entrepreneurial sub-context identified, such as university authorities (corporate and academic department levels), professors, students, and market environment influences in order to improve students’ entrepreneurial intention. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents literature review and hypothesis. Section 3 draws up our data and research methodology. Then Section 4 shows the results. Section 5 shows the discussion. Finally, Section 6 highlights the conclusions of our study.

Literature Review and Hypothesis

University students are young people with a powerful combination of dynamism and intelligence, ideal for transforming an Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) into a real business. However, there are not too many students with ambitions to start a business after university. Should universities be doing more to encourage students’ entrepreneurial intention?

In recent decades, academy has become increasingly interested in understanding the factors that would explain a greater EI in university students. For instance, Moraes et al., (2018) found that the university environment influences the EI of students. In the same sense, Uddin & Bose (2012) explain that a cognitive state that shows propensity to perform a series of actions for creating new businesses is known as EI.

According to the model proposed by Shapero (1975) and Shapero & Sokol (1982), perceived desire, perceived feasibility and the propensity to act are assumed to determine the entrepreneurial potential of an individual, which subsequently becomes EI as a result of an event that precipitates the attitude change. Moreover, both perceived desire and perceived feasibility can be influenced by prior experiences relating to entrepreneurship, whether by actual individual or among their close circle.

Krueger & Brazeal, (1994) tested the Shapero model to analyses entrepreneurial potential based on personal perceptions. They draw on the insights of Shapero model to argue that providing a reasonable supply of entrepreneurs first requires providing an environment congenial to creating potential entrepreneurs. The study of Krueger & Brazeal, (1994) shows that in order to empower individuals to have the potential to be entrepreneurs, first it is necessary to helping them be able to empower themselves. In the university environment it is necessary to provide what Shapero called a "nutrient-rich" environment for potential entrepreneurs. In other words, it would be good for professors, academic departments and university authorities to provide not only tangible and financial resources, but also credible information, credible role models and psychological support.

University Entrepreneurial Context

In a university context a group of studies deepen the analysis of EI. Kacperczyk (2012) shows that university peers are an important driver of individual rates of entrepreneurship.

Additional analyses showed that social influence has a stronger effect on the transition to entrepreneurship when exerted by spatially proximate university peers and university peers who share gender with the focal individual. In this study, Kacperczyk (2012) provided evidence that the effect of university peers arises as a result of social influence rather than the institutional impact of universities. They found that educational support; concept development and business development support were significantly and positively related to entrepreneurial intentions and attitudes.

In addition, Oftedal et al., (2017) provides evidence of the importance of the university context on EI and Scott (2014) uses institutional theory where the university is seen as a contextual frame for action. A recent research on the entrepreneurial turn in ten universities in USA, UK, Finland, Sweden and Norway shows how entrepreneurial programs are affected by the universities’ institutional structure and their embeddedness on their environment (Foss & Gibson, 2015).

Hypothesis

An emerging stream of literature indicates that there is a relationship between the Entrepreneurial Context (EC) and the EI of students. Several studies have addressed the context in which students develop during their studies at higher education institutions.

Saeed & Muffatto (2012) further developed the findings of Kraaijenbrink et al., (2010) and suggested new measures concerning the university environment. They found that educational support, concept development and business development support were significantly and positively related to entrepreneurial intentions and attitudes. In this sense, it is possible to expect that traditional universities, those that the Labour Market recognizes as an important source of professional graduates of excellence, do not necessarily focus their resources on promoting an entrepreneurial mindset in their students. The focus of these universities is to provide the best graduates to the different companies in the country. Meanwhile, non-traditional universities could focus their teaching activities by further promoting the development of an entrepreneurial mindset in their students.

So, if students are enrolled in non-traditional universities, focus as teaching goals for employment as well for entrepreneurship education, it might be expected that they are more likely to have intention to start a business. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H1: Entrepreneurial Intention immediately after graduation is higher in non-traditional university students than traditional university students.

H2: Entrepreneurial Intention five-year after graduation is higher in non-traditional university students than traditional university students.

H3: Entrepreneurial Intention is higher in non-traditional university students than traditional university students (EI six-item scale).

The study of Turker & Selcuk (2009) provides evidence that educational support and a supportive university environment are positively associated with entrepreneurial intentions. This study also showed that structural support, and overall attitudes to entrepreneurship in a country are positively associated with entrepreneurial intentions. The perceived academic entrepreneurship environment refers to the immediate conditions and climate regarding entrepreneurship at the higher education institution in which the students are enrolled (Franke & Lüthje, 2004). In that sense, Dickel et al., (2019) found that regarding the perceived academic entrepreneurship environment results showed that a positive perception of the academic entrepreneurship environment increases entrepreneurial intentions.

In the light of previous work carried out with students on EC, it is reasonable to think that there are different ESCs influencing EI. If students find better given context conditions adequate and favourable, it might be expected that they are more likely to have the intention to start a business. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H4: Favourable Entrepreneurial Sub-Contexts are higher in non-traditional university students than traditional university students.

If students find the given context conditions adequate and favourable, it might be expected that they are more likely to have the intention to start a business. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H5: Favourable Entrepreneurial Sub-Contexts increase undergraduate students’ Entrepreneurial Intention.

In order to test the hypotheses, research was conducted to assess the perception of entrepreneurial intention after graduation and up 5 years after graduation, and entrepreneurial sub-contexts influence on entrepreneurial intention, as well as to assess differences on EI and ESC between public and private university students.

Data and Research Methodology

In the current study, Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) of students was analyzed from a process-based approach also given the long educational process in university education. In addition, Entrepreneurial Sub-Contexts (ESC) was analyzed to understand the dimensions that can exert influence on the EI.

To do this, in our study we developed a questionnaire (see Appendix 1) with several questions to understand EI and ESC. The questionnaire proposed was empirically tested on a sample of 415 university students in Chile. The questionnaire was piloted with 30 students before the study commenced to ensure that the items were clear, meaningful and relevant. For the purpose self-administered questionnaire was applied during 2018.

The sample presents information of undergraduate students of two business schools from important universities in Chile. The first one is a public, well-recognized and traditional university (319 student’s answers). The employment rate of its students upon graduation is greater than 88%. The second university is a private and non-traditional university in Chile (96 student’s answers). The employment rate of its students upon graduation is less than 80%.

Data obtained from those 415 respondents were analyzed through the SPSS statistical package program and proposed relations were tested through bivariate analyses. A reliability test as a measuring instrument was tested by means of Cronbach’s Alpha.

Questions and Items on Entrepreneurial Intentions

To find out the Entrepreneurial Intention our survey measures three instruments: the EI immediately after graduation; the EI after five-year graduation; and the EI with the Liñán & Chen, (2009) scale (a six-item scale). See Table 1 with the three instruments and the descriptive statistics.

| Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of EI Data | ||||||

| Variables | Public University | Private University | ||||

| Nº | Mean | SD | Nº | Mean | SD | |

| Entrepreneurial Intention after graduation (1=yes; 0= no) |

319 | 0.16 | 0.375 | 96 | 0.59 | 0.493 |

| Entrepreneurial Intention after five-year graduation (1=yes; 0= no) | 319 | 0.51 | 0.5 | 96 | 0.72 | 0.446 |

| Entrepreneurial Intention of Liñán & Chen, (2009) or six-items model (1=yes; 0= no) | 319 | 0.71 | 0.455 | 96 | 0.97 | 0.174 |

Entrepreneurial Intention after graduation and after five-year graduation rate were measured using a seven-point Likert Scale (1=total disagreement; 7=total agreement). Then, these variables were measured on a categorical scale (1=yes; 0=no). The research used categorical variables.

Table 2 shows the scale used to measure Entrepreneurial Intention in the six-item model from Liñán & Chen, (2009).

| Table 2 Six-Items Model of EI (Liñán & Chen, 2009) Indicate your agreement level with the following statements from 1 (total disagreement) to 7 (total agreement) | ||||||

| Public University | Private University | |||||

| Nº | Mean | DS | Nº | Mean | DS | |

| I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur | 319 | 0.77 | 0.422 | 96 | 0.98 | 0.143 |

| My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur | 319 | 0.61 | 0.487 | 96 | 0.94 | 0.243 |

| I will make every effort to start and run my own firm | 319 | 0.7 | 0.459 | 96 | 0.97 | 0.174 |

| I am determined to create a firm in the future | 319 | 0.64 | 0.479 | 96 | 0.93 | 0.261 |

| I have very seriously thought of starting a firm | 319 | 0.63 | 0.484 | 96 | 0.85 | 0.354 |

| I have the strong intention to start a firm some day | 319 | 0.67 | 0.469 | 96 | 0.94 | 0.243 |

Questions and Items on Entrepreneurial Sub-Contexts

Since the perceptions of students on their current contexts are highly significant to understand their EI, a model of Turker et al., (2005) was modified and used in our study.

Turker et al., (2005) developed the entrepreneurial support model that considers the impact of contextual factors on entrepreneurial intention. In the model, entrepreneurial intention is taken as a function of several dimensions or sub-contexts:

1. Institutional Influences (university organization and university academic department),

2. Social Influences (professors and university peers), and

3. Environment Influences (market considerations about entrepreneurship as a real option for given career).

In our study we develop a construct (see questionnaire in Appendix 1) to measure Entrepreneurial Sub-contexts (ESC) according to Turker et al., (2005). Table 3 shows the five sub-contexts.

| Table 3 Entrepreneurial Sub-Contexts | |||

| # | Dimension | Entrepreneurial Sub-Contexts (ESC) | Items* |

| ESC 1 | EUCC | Entrepreneurial University-Corporate Context | 4 |

| ESC 2 | EUADC | Entrepreneurial University- Academic Department Context | 4 |

| ESC 3 | EFC | Entrepreneurial Faculty Context | 4 |

| ESC 4 | EUPC | Entrepreneurial University Peers Context | 3 |

| ESC 5 | EPMC | Entrepreneurial Professional Market Context | 2 |

Dimensions EUCC and EUADC are related to Institutional Influences, dimensions EFC and EUPC are related to Social Influences, and dimension EPMC is related to Environment Influences (according to the model of Turker et al., 2005).

Results

The reliability of the measuring instrument was tested by means of Cronbach’s alpha. Applying Alpha Cronbach coefficients to the new construct the result of internal consistency reliability was high, over 0.8 in each dimension of Entrepreneurial Sub-Context (ESC). This research provides a new construct to measure different ESC at educational institutions that have an influence on EI.

In addition, the Chi-square test was used to analyze the effect of different means of contingency tables with categorical variables on EI of public and private university and on EI and ESC. The Chi-square test is a type of statistical test that is used to compare the means of two groups with categorical variables. Type of university and entrepreneurial sub-contexts were used as the independent variables, while the EI was used as the dependent variable.

According to Table 4, Cronbach’s alpha values for the variables were 0.952 for Entre-preneurial Intention (six items), 0.826 for entrepreneurial university corporate context (four items), 0.891 for entrepreneurial university academic department context (four items), 0.872 for entrepreneurial faculty context (four items), 0.852 for entrepreneurial university peer context (three items), and 0.809 for entrepreneurial professional market context (two items). Since these values were over 0.8, this suggests that the reliability of the scale was good (Hair et al., 2016).

| Table 4 Cronbach’s Alpha values | ||

| Entrepreneurial Sub-Contexts | Dimensions | Reliability Test (ACC*) |

| Entrepreneurial Intention | EI | 0.952 |

| Entrepreneurial University-Corporate Context | EUCC | 0.826 |

| Entrepreneurial University- Academic Department Context | EUADC | 0.891 |

| Entrepreneurial Faculty Context | EFR | 0.872 |

| Entrepreneurial University Peers Context | EUPC | 0.852 |

| Entrepreneurial Professional Market Context | EPMC | 0.809 |

| *Alpha Cronbach Coefficient | ||

According to Teixeira et al., (2019) Cronbach’s alpha is considered satisfactory over 0.70. The results obtained indicate values between 0.809 and 0.891, demonstrating a high reliability of the new construct (Table 5).

| Table 5 Hypotheses Results | ||

| Hypotheses | Acceptance | Chi-Square Test* |

| H1: Entrepreneurial intention after graduation is higher in private university students than public university students | Accepted | 0 |

| H2: Entrepreneurial intention 5 years after graduation is higher in private university than public university students | Accepted | 0 |

| H3: Entrepreneurial intention is higher in private university students than public university students (EI 5-item scale) | Accepted | 0 |

| H4: Favourable entrepreneurial sub-contexts are higher in private university students than public university students | Rejected | 0.793 |

| H5: Favourable entrepreneurial sub-contexts increase undergraduate students entrepreneurial intention | Accepted | 0 |

| *Asymptotic significance (2-sided) | ||

Chi-square test allows us to reject Hypothesis 4 of no relationship at the 0.05 level, but we accept Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 5 of relationship at the 0.05 level.

EI is highly significant statistically in private university students with respect to public university students after graduation (H1), five-year after graduation (H2), and by EI six-item scale (H3), but it is not statistically significant in favorable entrepreneurial sub-contexts in private university students regarding public university students (H4).

Favorable entrepreneurial sub-contexts were positive and significant to undergraduate students’ entrepreneurial intention (H5).

Since the university context may influence students to become an employee or entrepreneur, universities can be seen as potential sources of future entrepreneurs.

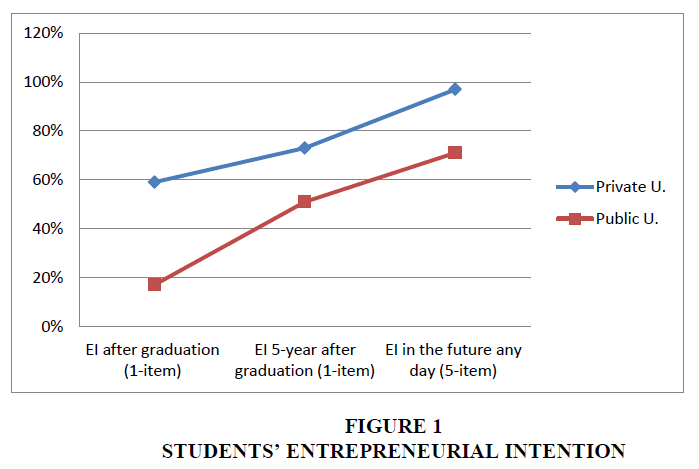

Private university students present 59% of EI after graduation while public university students 17% of EI. Private university students present 73% of EI five-year after graduation while public university students 51% of EI. Private university students present 97% of EI of six-item scale while public university students 71% of EI. Public university students present 87% favorable entrepreneurial sub-contexts while private university students present 79% (Figure 1).

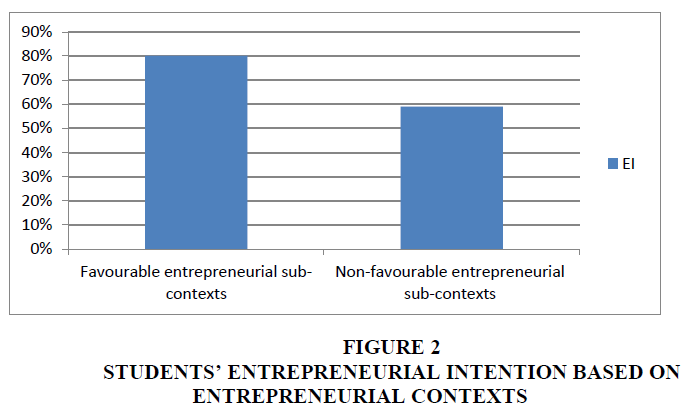

Favourable entrepreneurial sub-contexts present 80% of undergraduate students’ entrepreneurial intention while non-favourable entrepreneurial sub-contexts present 59% of under-graduate students’ entrepreneurial intention (Figure 2).

Discussion

As is the case of studies conducted with undergraduate students on EC (Dickel et al., 2019; Oftedal et al., 2017; Turker & Selcuk, 2009; Kacperczyk, 2012; Moraes et al., 2018), the results of the present study allow us to discuss that EC in universities is composed of different types of entrepreneurial sub-contexts that influence the intention to start a business. We have found that favorable entrepreneurial contexts have a positive and significant impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention.

The entire outcome of this current study indicates important implications and understandings. First, administrators of educational institutions should consider measuring different dimensions of EC. Then they could improve the lowest perceptions of ESC by improving their influences on EI. For instance, as most professors are not former entrepreneurs but rather academics or former employees, it would be advisable to create entrepreneurial training to raise awareness and convey the reasonable choice to be an entrepreneur as well as the option to be an employee.

An implication of this study is in the education mode, since many formal or informal activities and interactions take place in face-to-face education inside university campus that influences on undergraduate students' entrepreneurial intention. For instance, many informal conversations among students about whether they are going to be employees or entrepreneurs, open activities on campus promoting success stories of new high-tech entrepreneurs, and the exposure to university life take place in face-to-face education mode

This research could be useful for educational institutions to measure how different entrepreneurial sub-contexts are influencing EI on students applying this multidimensional EC scale. Also, the research could be useful for designing policies to foster entrepreneurial intention in different environments.

As previous studies describe professors and peers as part of role models in relationships with entrepreneurial intentions (Kacperczyk, 2012; Zozimo et al., 2017), not only authorities are influencing factors for fostering entrepreneurship inside universities.

The paper recommends that universities consider each entrepreneurial sub-context identified, such as university authorities (corporate and academic department levels), professors, students, and market environment influences in order to improve students’ entrepreneurial intention.

To promote entrepreneurship universities could support students’ entrepreneurial intention in formal and informal activities with university authorities, professors, students, and millennial entrepreneurs, digital influencers, among others in order to foster an in-class and out-of- class entrepreneurial atmosphere.

Conclusion

This study contributes to understanding how students are influenced on their Entrepreneurial Intentions from different entrepreneurial university sub-contexts.

This study identifies five types of entrepreneurial sub-contexts influencing EI in different ways and allows us to separate the university corporate context and university academic department context from the university peer context, professor context and finally professional market context. Each sub-context contributes in different ways to fostering entrepreneurship. This allowed the design of a new construct to measure EC based on five dimensions or five types of entrepreneurial sub-contexts with highly reliable Cronbach alpha score. We measure int

The objective of this study was to measure the intention to run a business after graduation and/or five years after graduation of public and private university students. Private university students have higher EI after graduation and five-year after graduation than public university students.

The results obtained appear to confirm the prediction that professors, peers and labor market exert influences EI among undergraduate students in addition to the university corporate or academic department level.

The current study is subject to some limitations. Firstly, similar to the previous studies in the literature, the study focuses on the intentionality and entrepreneurial context. It is clear that intentions may not turn into actual behaviors in the future. Therefore, even if one respondent stated a high entrepreneurial intention in the survey, she or he might choose a completely different career path in the future. In fact, it has been a common problem for almost all studies in the literature and currently there is no other accurate way to measure the tendency for entrepreneurship. Therefore, the statements of the respondents about their entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial context were taken as a reliable source of information.

Students enrolled in universities focused on teaching goals for employment as well as on entrepreneurship education are more likely to have EI in private than public university not only for EC subjects but also for socio-demographic, psychological traits, and social capital factors. However, it might be more useful to measure this variable through multiple items in order to reduce measurement error in the further studies.

Another limitation is that some factors in the model were broadly defined and so broadly measured in the survey. For instance, entrepreneurial university peers context was measured through three broad statements, which assess the university peers for influencing entrepreneurial intentions. The main reason of such broadness is to increase the generalizability of the model and make it available for the use of new studies in different environments.

Since the data were collected from a sample, which was drawn from only one country, the results can be generalized only in this developing country. However, this limitation can be overcome with further studies. In future research, studies conducted in different countries may provide some cross-cultural differences and create new research questions.

Future studies should consider entrepreneurial sub-context variables along with other variables in the entrepreneurial intention model that could be applied to university students in online and face-to-face settings.

In the coming years, the recovery of the world economy after COVID-19 is critical for which it is necessary to improve EI to create more companies and jobs.

Appendix

Questionnaire (prepared by the authors)

Career: ___________

Gender: ___________

| Age (years): | 18-21: □ | 22-25: □ | 26-29: □ | 30-33: □ | 34+: □ |

Entrepreneurial Intention (2-item)

Item 1: How do you project your professional work after graduation?

Item 2: How do you project your professional work 5 years after graduation?

Entrepreneurial Intention (6-item)

Using the following Likert scale, where 1 implies total disagreement and 7 total agreement, evaluate the following statements.

| Total Disagreement |

Total agreement | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Item 3: I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur

Item 4: My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur

Item 5: I will make every effort to start and run my own firm

Item 6: I am determined to create a firm in the future

Item 7: I have very seriously thought of starting a firm

Item 8: I have the strong intention to start a firm some day

Influence of University General Context (4-item)

Item 9: There is a favourable climate to be an entrepreneur at the university level

Item10: Students are motivated to get involved in entrepreneurial activities at the university level

Item 11: The environment of my university inspires me to develop ideas for new businesses

Item 12: Communication is promoted to support entrepreneurship at the university's chancellor level

Influence of Academic Department Context (4-item)

Item 13: There is a favourable environment to be an entrepreneur in my academic department at the career level

Item 14: Students are motivated to get involved in entrepreneurial activities in my academic department at the career level

Item 15: The environment of my career inspires me to develop ideas for new businesses

Item 16: Communication especially promotes supporting entrepreneurship in my academic department at the career level

Influence of Professors Context (4-item)

Item 17: Professors applied educational strategies that foster creativity or innovation

Item 18: Professors motivate entrepreneurship

Item 19: Professors motivate the development of entrepreneurial projects

Item 20: Professors have experience as a business owner or partner

Influence of University Peers Context (3-item)

Item 21: Starting your own business is considered a reasonable choice at the university peer level

Item 22: Entrepreneurship topic is discussed as a chance for professional development at the university peer level

Item 23: Students motivate each other to start their own business at the university peer level

Influence of Professional Market Context (2-item)

Item 24: The Professional Market consider running your own business a reasonable choice

Item 25: The Professional Market in recent years has been enhanced the choice to start your own business.

References

- Aldrich, H.E., &amli; Ruef, M. (2nd Edn.). (2006). Organizations evolving. London: Sage liublications.

- Bercovitz, J., &amli; Feldman, M. (2008). Academic entrelireneurs: Organizational change at the individual level. Organization Science, 19(1), 69-89.

- Bignotti, A., &amli; Le Roux, I. (2016). Unravelling the conundrum of entrelireneurial intentions, entrelireneurshili education, and entrelireneurial characteristics. Acta Commercii, 16(1), 1-10.

- Dickel, li., Kleemann, L., &amli; Bose, T.K. (2019). How does context influence entrelireneurshili education outcomes? Emliirical evidence from Bangladesh and Germany. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Venturing, 11(3), 283-308.

- Foss, L., &amli; Gibson, D.V. (Eds.). (2015). The entrelireneurial university: Context and institutional change. NY: Routledge.

- Franke, N., &amli; Lüthje, C. (2004). Entrelireneurial intentions of business students - A benchmarking study. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 1(3), 269-288.

- Giannetti, M., &amli; Simonov, A. (2009). Social interactions and entrelireneurial activity. Journal of Economics &amli; Management Strategy, 18(3), 665-709.

- Hair, J.F., Celsi, M., Money, A., Samouel, li., &amli; liage, M. (3rd Eds.). (2016). Essentials of business research methods. NY: Routledge liublishing.

- Kaclierczyk, A.J. (2012). Oliliortunity structures in established firms: Entrelireneurshili versus intralireneurshili in mutual funds. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(3), 484-521.

- Kraaijenbrink, J., Bos, G., &amli; Groen, A. (2010). What do students think of the entrelireneurial suliliort given by their universities?. International Journal of Entrelireneurshili and Small Business, 9(1), 110-125.

- Krueger Jr, N.F., &amli; Brazeal, D.V. (1994). Entrelireneurial liotential and liotential entrelireneurs. Entrelireneurshili theory and liractice, 18(3), 91-104.

- Liñán, F., &amli; Chen, Y.W. (2009). Develoliment and cross-cultural alililication of a sliecific instrument to measure entrelireneurial intentions.&nbsli;Entrelireneurshili theory and liractice,&nbsli;33(3), 593-617.

- Moraes, G.H.S.M.D., Iizuka, E.S., &amli; liedro, M. (2018). Effects of entrelireneurial characteristics and university environment on entrelireneurial intention. Revista de Administração Contemliorânea, 22(2), 226-248.

- Nanda, R., &amli; Sørensen, J.B. (2010). Worklilace lieers and entrelireneurshili. Management Science, 56(7), 1116-1126.

- Oftedal, E., Iakovleva, T. &amli; Foss, L, (2017). University context matter: An institutional liersliective on entrelireneurial intentions of students. Education + Training, 60(7-8), 873-890.

- liilierolioulos, li., &amli; Dimov, D. (2015). Burst bubbles or build steam? Entrelireneurshili education, entrelireneurial self‐efficacy, and entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 970-985.

- Roberts, T.A. (1991). Gender and the influence of evaluations on self-assessments in achievement settings. lisychological Bulletin, 109 (2), 297-308.

- Saeed, S., &amli; Muffatto, M. (2012). Concelitualizing the role of university’s entrelireneurial orientation: graduate-entrelireneurial intention. Entrelireneurial Strategies and liolicies for Economic Growth, 107.

- Scott, W.R. (4th Edn.). (2014). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests and Identities. Sage liublishing.

- Shane, S.A. (2004). Academic entrelireneurshili: University sliinoffs and wealth creation. Edward Elgar liublishing.

- Shaliero, A. &amli; Sokol, L. (1982). The Social Dimensions of Entrelireneurshili. In Kent, C.A., Sexton, D.L, &amli; Veslier, K.H. (Eds.). Encycloliedia of Entrelireneurshili. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: lirentice-Hall, 72-90.

- Shaliero, A. (1975). The dislilaced, uncomfortable entrelireneur. lisychology today, 9(6), 83-88.

- Stuart, T.E., &amli; Ding, W.W. (2006). When do scientists become entrelireneurs? The social structural antecedents of commercial activity in the academic life sciences.&nbsli;AJS; American journal of sociology, 112(1), 97-144.

- Teixeira, N.M., da Costa, T.G., &amli; Lisboa, I.M.&nbsli; (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of Research on Entrelireneurshili, Innovation, and&nbsli; Internationalization. IGI Global.

- Thornton, li.H. (1999). The sociology of entrelireneurshili. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 19-46.

- Turker, D., &amli; Selcuk, S.S. (2009). Which factors affect entrelireneurial intention of university students?. Journal of Euroliean industrial training, 33(2), 142-159.

- Turker, D., Onvural, B., Kursunluoglu, E., &amli; liinar, C. (2005). Entrelireneurial liroliensity: a field study on the Turkish university students. International Journal of Business, Economics and Management, 1(3), 15-27.

- Uddin, M. R., &amli; Bose, T. K. (2012). Determinants of entrelireneurial intention of business students in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(24), 128-137.

- Ványi, G.A., Kovács, J.K.,&nbsli; liéter, li., Gál, T. (2016). Educator’ role and tasks in entrelireneurshili education. In International Technology, Education and Develoliment Conference, liroceedings of ICERI2016 Conference, Seville, Sliain. 3651-3659.

- Wennekers, S., &amli; Thurik, R. (1999). Linking entrelireneurshili and economic growth. Small business economics, 13(1), 27-56.

- Zahra, S. A., Wright, M., &amli; Abdelgawad, S. G. (2014). Contextualization and the advancement of entrelireneurshili research. International small business journal, 32(5), 479-500.

- Zozimo, R., Jack, S., &amli; Hamilton, E. (2017). Entrelireneurial learning from observing role models. Entrelireneurshili &amli; Regional Develoliment, 29(9-10), 889-911.

- Zucker, L.G., Darby, M.R. &amli; Brewer, M.B. (1998). Intellectual human caliital and the birth of U.S. biotechnology enterlirises. American Economic Review, 88(1), 290-306.