Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 1S

Exploratory Research Semiotics & Globalization - Exploring the marketing landscape of Kuwait

Saud Buhamdi, Kuwait Technical College

Farah Al Saeed, Kuwait Technical College

Randa Diab-Bahman, Kuwait Technical College

Anwaar Alkandari, Kuwait Technical College

Citation Information: Buhamdi, S., Al Saeed, F., Diab-Bahman, R., & Alkandari, A. (2023). Exploratory research semiotics& globalization - exploring the marketing landscape of kuw ait. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 26(S1), 1-14.

Abstract

Synopsis: This investigative research explores the language landscape and semiotics used throughout the country in advertising. The research probes into the language visibility and contact with the intended audience and breaks down the basics of marketing dynamics at play. Though there is a plethora of information on the topic of semiotics and advertisement outcomes in general, there is a dearth of information available from the MENA region âÂÂ?ÂÂ? particularly Kuwait. Given that the area is a melting pot of different ethnicities and social norms, language preferences are not as easily defined or understood. Aim: The purpose of the research is to explore ways in which semiotic analysis is applied in the marketplace, particularly in advertising on billboards. The aim is to have a better understanding of the different semiotics strategies used throughout the local marketing arena. Though the official language of the country is Arabic, there are many aspects of marketing which cater to the broader local audience. Thus, plenty of semiotic strategies are employed to tackle the needs of the local market. The key focus of this study is to briefly analyze these advertisements using a semiotics analysis to formulate an understanding of the different strategies that advertisers use to communicate to their target customers in a multi-cultural society. Research Significance: This research will be one of the first to investigate the local marketing landscape from a semiotics lens. The findings will be important to practitioner and policy makers as they will help further determine the pros and cons of the different methods presented to the local stakeholders. Methodology: The data collection included a walk is used to assess the differences of the conventional billboard advertisements within different regions of Kuwait. The data is quantified, presented and discussed to better understand the practices and needs of the target audience at hand. Throughout the six Kuwaiti governorates, more than 2000 outdoor billboards were analyzed for variances in semiotics and language uses. Findings: The findings conclude that the majority of the LL in Kuwait included bilingual advertisements, with the majority using the English language, and that there were differences amongst the six different governorates. We interpret these findings in the LL of Kuwait as a reflection of the steady changes that are happening locally and regionally

Keywords

Semiotics, Linguistic Landscape, Marketing, Advertising, Kuwait.

Introduction

With ever-changing and expanding consumer bases, marketing strategies need ongoing assessment of marketing communications intending to sensitize marketing approaches to the cultural norms. This approach of utilizing multicultural perspectives in the curation and advertising of marketing communication is known as cross-cultural marketing. Going global no longer means physically expanding into various locations; with digitalization, consumer bases extend beyond the physical borders of a brick-and-mortar location as cross-cultural marketing can be defined as the art of taking one culture and connecting it to other cultures by sharing their commonalities, rather than focusing on or erasing their differences. In today’s globalization era toppled by digitalization, efforts to employ a cross-cultural marketing strategy have become crucial (Kivenzor, 2018). Employing various forms of semiotics is an effective tool for developing cross-cultural strategies. Visual identities, for example, companies’ logos, can evoke the same meaning across diverse cultures. “From a research point of view, semiotics is just about stepping back from the consumer and looking at the culture” (Stephen Gossett, 2022).

Moreover, consumer profiling is one of the most critical stages in the formation of any marketing strategy. Consumers from diverse cultures experience different sensory worlds and use different criteria to interpret behavior (Lee & Lopetcharat, 2017). According to a study that utilized a visual rhetorical approach to interpretations, pictures are not universal; visual interpretations vary as viewers use culturally-sited advertising knowledge and visual signs to interpret commercials (Bulmer & Buchanan-Oliver, 2006). The revelation of understanding the effects that differences in culture have on interpretation has sparked marketing research to focus on the power of commonalities between cultures. Today, with digital transformation and the era of big data, consumer profiling approaches have revolutionized (Verdenhofs & Tambovceva, 2019). A deeper understanding of consumers follows a deeper understanding of the utilization and effectiveness of semiotics in marketing. For instance, employing one of the considerably basic tools of visual semiotics, color, can vary based on your consumer segmentation. The impact of color selection in marketing communication is powerful. Colors can shape people’s gut reaction to brands without being explicitly recalled (DharmaKeerthi & Ranjan, 2010). Moreover, according to Angermeyer advertising, in general, may be seen as seeking to appeal to a specific group of potential addressees by invoking a common social, cultural and linguistic identity. Thus, it is critical to identify who is meant to receive the marketing communication to assess the LL. One can go further and examine the virtual LL, which has been argued to reflect the physical location relevant to it (Kellerman, 2010). Furthermore, according to Hiippala et al. (2019), qualities associated with the physical place may be carried over to the corresponding virtual space.

Moreover, a significant amount of research has been dedicated to understanding factors that influence consumer purchase intent. Also, many of those factors, such as brand image, apply the use of semiotics. One of the most fundamental yet revealing cases of semiotics on consumer purchase intent is product packaging. A study that examined packaged food products found that product packaging significantly affects consumers' purchase intentions. It was revealed that “packaging material has the strongest influence on consumer purchase intentions followed by packaging color, font style, packaging design, and printed information.” According to DharmaKeerthi & Ranjan (2010), the recent integrative approach to developing brand images employs a range of semiotics symbols and signs. Research conducted in the industry of hospitality concluded that there is a direct influence between brand image and purchase intent. Purchase intent increases when a consumer resonates with a brand’s image (Lee & Lopetcharat, 2017).

Literature Review

History of Linguistic Landscape Research

As the field has massively grown within the last twenty years, this expansion has enabled researchers to investigate the Linguistic Landscape (LL) of many unique and interesting topics. Discussing topics such as schools (Dressler, 2015; Gorter, 2006), private home signs (Laihonen, 2016), tourism (Bruyel-Olmedo & Juan-Garan, 2015) prints on T-shirts Caldwell (2017), and even underwater diving sites (Nash, 2013). The broad range of productive topics and discussions that LL are now offering to the world of linguistics, semiotics, and ethnography has shaped the field into a much broader concept than the documentation of signs (Blommaert, 2013).

The period between 1997 and 2006 enjoyed a noticeable growth in LL studies and was vital to the development of the field. The three most prominent contributions during this time period includes: naming the field Landry & Bourhis (1997) establishing the units of data Landry & Bourhis (1997); Gorter (2006) and the formation of some of the theoretical frameworks for these studies (Scollon & Scollon, 2003). Scollon & Scollon (2003) conducted an LL study that contributed a significant theoretical view in their multi-city research. Although they peculiarly named their field of study geosemiotics, their study still had a substantial impact on the theoretical LL underpinnings. They explored language use on signs in several locations around the world in what they called ‘semiotic aggregate.' Scollon &Scollon (2003) claimed that any given cityscape is formed from a variety of unique discourses called semiotic aggregate. They were able to emphasize the dynamic relationship between language and space with the way they interact and affect each other to provide different meanings in different contexts.

Use of Semiotics in Marketing

One of the major studies conducted and published during this period was Backhaus (2007) study of multilingualism in the city of Tokyo. Backhaus (2007) pursued to analyze Tokyo's LL using a simple framework of three questions that contained nine analytical categories. The first two analytical categories of languages contained and the combination of languages helps to understand the essential multilingual nature of Tokyo's LL. The first research question deals with who contributes to the making of the LL and includes analytical categories: top-down vs. bottom-up, geographic distribution, and code preference. The second question addresses the problem of whom the LL will serve and includes: part-writing and visibility. The final question deals with the diachronic language situation and focuses on idiosyncrasies and layering. Backhaus (2007) well-defined three-point methodological system was an efficient way of collecting the data needed for the study. In this system, he first determined the survey areas by selecting the circular Yamanote railway line of 29 stations that connect Tokyo's main city centers. Backhaus (2007) then determined the countable items found in the signs that he collected, and then made the multilingual and monolingual sign distinctions. He found in his results that the non-official bottom-up signs constitute 70% of the 2444 multilingual signs collected vs. the 30% of the total number of official signs. Some differences noticed between the two types of signs, mainly in the limited number of languages displayed (Japanese, English, Chinese and Korean) and the prominence of Japanese in the official signs. Much like other LL studies conducted previously, the non-official signs tended to include a wider variety of languages and did not have the same code preference that favored Japanese. Backhaus (2007) inferred that this was the consequence of the notable increase in the linguistic minority groups had made Tokyo their home. Most notably, the Chinese and Korean communities that have started to make their presence felt, especially within the western and northwestern parts of the Yamanote Line.

Furthermore, Backhaus (2007) found that multilingual signs were divided into two groups. On the one hand, multilingual signs that included translations and transliterations of Japanese and they are intended for the non-Japanese reader. On the other hand, he has found the other group of signs for the Japanese reader that contained both Japanese and English in a complementary way rather than a direct translation of each other. The layout of these Japanese reader signs has allowed Backhaus (2007) to determine the local linguistic profile of these readers. English is mostly commissioning to the titles, slogans, and business names, and Japanese for additional information of a specific nature. This arrangement implies that the typical Japanese reader had at least a minimal degree of English proficiency to be able to read and understand a Japanese sign at the time. Additionally, Backhaus (2007) has found that the majority of non-official multilingual signs to have their multilingual nature visible, with added translated foreign text in many languages to make the sign appear less monolingual. Armed with his complete results and the previous findings of Someya (2002) and Inoue (2005), he concluded that the increase of visibility of languages and scripts other than Japanese in Tokyo is the result of three factors. First, the Japanese people's welcoming attitude and hospitably towards foreign languages, and especially English. Second, the relaxed government language policies aimed at the internationalization of Tokyo. Third, the growing share of non-Japanese residents in some parts of the city. Although Backhaus (2007) used a wide-ranging set of methodologies to analyze the quantitative data, however, his lack of qualitative outlook on the signs in this survey may have limited his results and claims.

Moreover, outside of Tokyo in the urban city of Fukuoka, Kallen & Ni Dhonnacha (2010) have found that the Japanese language is still the prominent language of culture and national unity. However, English was present in a large number of signs across Fukuoka, most of which do not intend to cater to English language speakers. Kallen & Ni Dhonnacha's (2010) findings are similar to the findings of Aristova (2016), Backhaus (2007) & Inoue (2005), and revealed that in most cases the presence of English was merely a signifier of modernity and embracing globalization. In fact, most of the English found on these signs was unusual and sometimes even incomprehensible. Their findings in Fukuoka, as well as their investigation of the Irish language in Galway and Dublin, suggest that we cannot interpret language use. Instead, their use is often indexical and offers a metaphorical reference to their language choice, writing style, and font. In Japan, the use of English is often "indexical to modernity and post-modern hybridity..." (Kallen & Ni Dhonnacha, 2010). Similarly, Lou (2010) had witnessed that the visual and material prominence of Chinese in Chinatown is being gradually diminished in the place of larger corporate logos. Many of these corporate signs now no longer contain Chinese characters and the Chinatown color scheme as their central theme, but have significant English characters and corporate color schemes with much smaller Chinese characters "added on." Moreover, most of these signs do not contain a translation of the name to Chinese, but a vague description of what they sell in those stores. This semiotic marginalization continues in the community approval meetings, where the Chinese language seemed to be devalued resource as a result of second and third generation American-Chinese community members with low attachment to the language.

Impact of Globalization

The impact of English as an international communication agent and its effects on the development of the LL of cities seem to stretch to all corners of the globe. For Takhtarova et al. (2015), they set out to find the role of English as an international language in three European cities: Paris, Berlin, and Kazan. Moreover, they sought to find the efforts of each city of preserving their language and culture in the face of imminent globalization. It goes without saying that in this modern era of globalization that commitment to native languages and culture struggles to compete with the appeals of English as a global communication language and financial tool for joining the international market. Their research has found abundant English usage in advertising, trade, business and everyday life in three of the cities. They deemed the results unavoidable and potentially explained by the necessity to meet the requirement and expectations of the population, especially that of the younger generations. Similarly, a study conducted in Athens by Nikolaou (2017) that investigates multilingualism on shop signs saw similar findings to Takhtarova et al. (2015). Nikolaou (2017) found English to be of high prominence in the LL of Athens and is commonly used as the primary marker in signs as a symbolic language. The investigation of its functions revealed that English usage in Athens is not principally aimed at foreign visitors or English speakers but as a symbolic expression of values and ideologies. Greek was the language of choice a secondary marker, which fulfills a more utilitarian and functional purpose. These findings are similar to the findings of Al-Athwary (2017) in Yemen, where the name, logo, and slogan of the business are placed using English, and additional information about the product is communicated using the local language. Kachru (1982) explains that English in many parts of the world is slowly transforming from a performance language into a quasi-institutional variety.

Local Landscape – Kuwait

Kuwait is divided into six governorates. Each governorate has its unique population and nationality distributions, as well as its unique style. They include Farwaniya Governorate, Ahmadi governorate, Hawalli governorate, Capital governorate, Jahra governorate, and finally Mubarak Al-Kabeer governorate as shown in detail below Table 1.

| Table 1 Population Distribution By Governorate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Governorate | Kuwaiti Population | Non-Kuwaiti Population | Total |

| Farawaniya | 236,433 | 932,879 | 1,169,312 |

| Ahmadi | 286,707 | 672,302 | 959,009 |

| Hawalli | 230,759 | 709,033 | 939,792 |

| Capital | 255,540 | 313,027 | 568,567 |

| Jahra | 185,819 | 355,091 | 540,910 |

| Mubarak Al-Kabeer | 156,451 | 98,458 | 254,999 |

Official governing bodies are wary of the threat of Arab identity in Kuwait, and thus create their language policies and configurations implemented on government-issued signs. Government issued signs involve the use of Arabic names, occasionally supplemented by the transliterated English text below the Arabic text The popularity of Western imported goods is witnessed in many corporate shops, advertisements, and billboards, and are clearly contributing in driving the visible prominence of English usage in signs all over Kuwait. More significantly in the Capital and Hawalli governorates that represent the cosmopolitan centers of Kuwait. The non-Arabic speaking residents of Kuwait that represent almost half of the population are not adequately expressed in the linguistic landscape. The visibility of these languages is mostly limited to specific shopping areas that cater to these nationalities. The expectation is that these expatriates are able to read and write English may contribute to increasing the visibility of English in Kuwait further. Thus business owners and advertisement agencies can target all non-Arabic speaking expatriates by using English in their signs. Favorable use of English as the main language of branding, Arabic as the main language of code preference, and the borrowing of English expressions and words that have made their way into the local signs and speech supports the implication that English is highly valued for its symbolic use. The value of English is especially prominent in the commercial sector where we observe high English usage in branding, advertisement posters and billboards. This high value that is attached to English, however, is not necessarily accurate in Kuwait’s communicative setting. Finding out differences in communicative patterns and language use could be uncovered in another future research (Stephen Gossett, 2022).

The six different governorates of Kuwait that follow three distinct characteristics that can affect its LL. The three characteristics are identified as cosmopolitan, metropolitan and suburban governorates, and they appear more global and multinational respectively. Capital and Hawalli governorates are perceived as cosmopolitan, which can influence the linguistic behavior of its residents and business owners to adopt international global languages like English more regularly. Jahra and Mubarak Al-Kabeer appear to be very suburban with large populations of Kuwaitis compared to other governorates. This feature may restrict the linguistic behaviors of its residents and business owners from using multilingual signs and to appear more traditional with substantial use of Arabic in signs, coding preferences, and branding. A number of examples indicate that the presence of English suggests a depiction of internationalism and quality. Edelman 2007 describes that advertisers and branding experts incorporate English and other global languages not necessarily to be understood but to appeal to emotions and the anticipation of the reader through the connotations of language. Additional studies such as Piller (2001) and Edelman 2007 prove that the use of English and other foreign languages in mass media around the world does not necessarily reflect the everyday language use of its people. This concept is termed ‘impersonal multilingualism,' where the use of foreign languages is not proposed as a means of communication but rather to appeal to people's emotions towards the product.

Most importantly, is the high number of English speaking expatriates that reside and work in the Kuwait, which imposes the bilingualism that has appeared in the local LL. The role of Arabic as the official national language and its sociopolitical role in advocating Arab nationalism now face extreme pressure from both the people of Kuwait who are embracing the globalized market and from the power of English as a global communication world language and as a vital commercial tool. The English language is associated with values such as international orientation, modernity, success or sophistication (Piller, 2001). In the same context, Aristova (2016) and Cenoz & Gorter both note the use of English is tied to economic motives as businesses use highly prestigious languages have a direct impact on their profit and success. Other scholars attribute the commercial use of the English language on signs to its role as a symbol of internationalism, westernization, modernity, success, and attractiveness (Aristova, 2016; Gorter & Cenoz, 2018). Due to the different dynamics are play, it is important to explore the local LL diversity. Languages contained and their combinations are both factors which will enable the identification of not only the appearance of languages and their combinations in the LL of Kuwait, but also provide an overall impression of the monolingual, bilingual or multilingual nature of the signs as well as language varieties.

Methodology

The framework was applied by analyzing a collected sample of 2204 signs throughout the six governorates of Kuwait. It was natural, therefore, to decide to use the official six governorates as a basis for comparing and contrasting the data. As each governorate has its unique population and nationality distributions, as well as its unique style. However, the method by Backhaus (2007) to choose the railway lines as geographical markers were out of the question as Kuwait's metro system is still in its early development. The alternative was similar to what Huebner 2006 had used in his LL study in Bangkok by selecting the main sections of the shopping streets. In the case of Kuwait, the decision is to pick the main shopping streets in each of the six governorates. After careful consideration, studying the areas and asking friends and family about the primary locations in each of the governorates, the locations were chosen.

For this study, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies is used to analyze the data. However, the data is primarily quantitative, with a few examples of signs selected to be qualitatively analyzed. Recently there have been a growing number of researchers such as Coluzzi (2016), and Troyer et al. (2017) that are using quantitative and qualitative approaches to combine the strengths of both methods for a more comprehensive analysis of the LL. As each governorate has its unique population and nationality distributions, as well as its unique style, the main shopping streets were chosen in each of the six governorates. One disadvantage of choosing the main shopping streets, however, is that the appearance of languages can alter towards being more diverse. Outside of these main busy shopping streets it would be harder to find foreign languages such as French, Hindi and Bengali as they are not represented as heavily outside these areas.

The count of languages is based strictly on the appearance of language characters rather than meaning. Simplicity and time consumption were the two justifications for counting languages based on characters, as spotting language characters is easy compared to reading other than Arabic and English. Additionally, there were a high number of phrases that had elements of two or more languages; therefore it would have taken a significantly longer time to break down and assign to the different languages. An Example of this phenomena would be the phrase "MARWAN SHOPPING CENTRE LIL SAYIDAAT" where it would count as English for containing English scripture, rather than Arabic and English for containing Arabic "LIL SAYIDAAT" (meaning for women) and English "SHOPPING CENTRE." Consequently, the signs were categorized, distinguished and grouped based on the visual appearance of languages and their combinations.

Findings

Qualitative Examination

The aim of this study is to scope the local LL of Kuwait on a macro level and present some unique cases of monolingual, bilingual and multilingual signs found. The results disclosed that the majority of signs were bilingual signs, appearing in just over 50% of the sample size. Monolingual signs appeared in almost 47% of the total signs, leaving the remaining multilingual signs to be found in just over 2% of the sample size. As for the languages found in these signs, Arabic is observed in 77% of the total signs collected. Similarly, English is found in just over 70% of the sample, and other languages such as Hindi (3%), Bengali (2%) and Tagalog (1%) are found in much smaller percentages as seen in the 2A & 2B:

| Table 2A Semiotics Variances In Kuwait Ll (By Governorate) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SignsIn Governorate | Count | Mono | Bi | 3 Lang | 4 Lang | 5 Lang | Multi |

| Farwaniya | 297 | 144 | 149 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Ahmadi | 400 | 180 | 208 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Hawalli | 400 | 127 | 270 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Capital | 500 | 214 | 263 | 15 | 5 | 3 | 23 |

| Jahra | 349 | 211 | 134 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Mubarak Al-Kabeer | 258 | 156 | 97 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Total | 2204 | 1032 | 1121 | 42 | 6 | 3 | 51 |

| Table 2B Semiotics Variances In Kuwait Ll (By Method) |

|

|---|---|

| Number of languages | Percentage |

| Mono | 46.8% |

| Bi | 50.8% |

| Multi | 2.3% |

Romanized Arabic Vs Arabized English

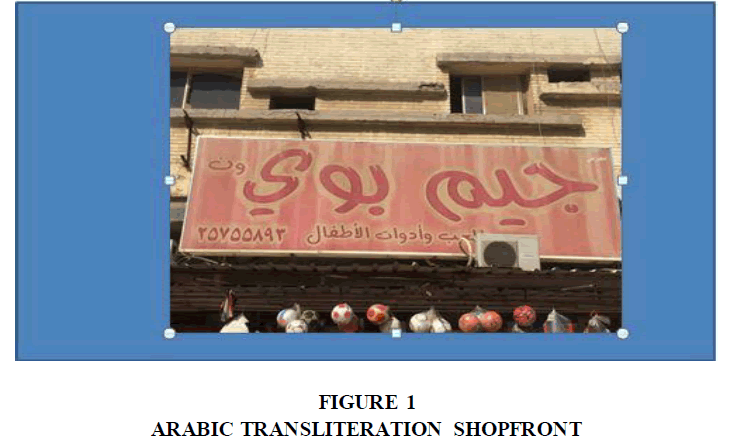

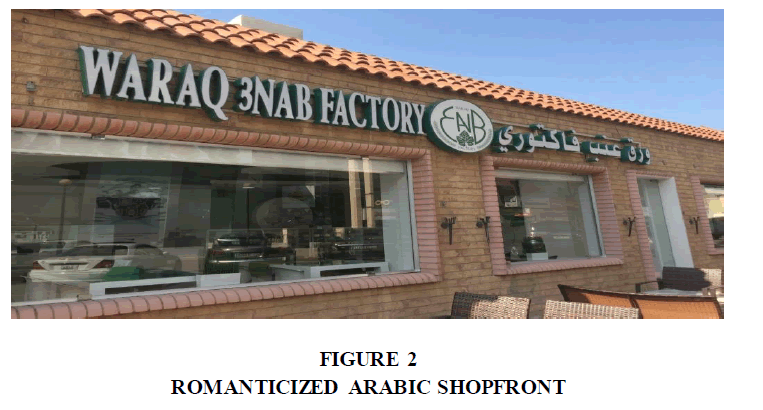

Furthermore, by observation and field notes table 3, it seems that two of the most common language varieties found in the LL of Kuwait are Romanized Arabic (RA) and Arabized English (AE). Al-Athwary (2017) clarifies RA as Arabic text written in Roman script, while AE involves English words inscribed in Arabic script. According to Alomoush (2016), the use of these varieties of language in the LL provides three key benefits: first in advocating linguistic tolerance and local identity, second in promoting local names and cultural references, and third in creating new functions, including reformed lexical needs and synonyms. The use of AE and RA is designed to emphasize the importance of modernism, high quality, and compromise by using AE in Arabic characters. These language varieties, and especially AE, are found abundantly in the LL of Kuwait. The popularity of written English (whether as Arabized English or traditional English) has altered them into popular mediums for marketing success, modernity and the embracing Western culture (Al-Athwary, 2017). This concept is especially valid for higher social classes in Kuwait, and the Middle East (Alomoush, 2016). Figure 1 and Figure 2 offer two typical examples of AE usage in Kuwait. In Figure1, the AE appears alongside English text as a window graphics sign on a beauty shop. The AE is a direct Arabic transliteration of the name of the shop "Faces." The lack of Arabic translation of the name, replaced by the transliterated Arabic version of the word "Faces" hints that the business owners wanted to convey global brand flair. Inspecting the shop and searching it on the Internet reveals that the shop is a local business selling international beauty products. A similar branding strategy is spotted for certain types of businesses, and more specifically stores that sold international products. Shops such as beauty stores, fast food restaurants, gyms, clinics, clothes and mobile phone stores typically use English branding accompanied by the Arabic transliteration as seen in the figures below:

| Table 3 Language Combinations (Multilingual Signs) |

|

|---|---|

| Language Combinations in bilingual and multilingual tokens | Count |

| Arabic, English | 1033 |

| English, Hindi | 30 |

| English, Tagalog | 17 |

| Arabic, English, Hindi | 15 |

| Arabic, English, Bengali | 12 |

| English, Bengali | 9 |

| English, Sinhalese | 8 |

| Arabic, French | 4 |

| Arabic, English, Farsi | 4 |

| English, Urdu, Bengali, Hindi | 3 |

| Arabic, English, French | 3 |

| Arabic, Bengali | 2 |

| Arabic, English, Urdu, Bengali, Hindi | 2 |

| English, Nepali | 2 |

Discussion

It is no surprise that the combination of Arabic-English was the most popular language combination among bilingual and multilingual signs. In fact, this combination is witnessed in 92% of the bilingual signs and around 47% of the total signs. Other combinations such as English-Hindi, English-Tagalog, Arabic-English-Hindi, and Arabic-English-Bengali are occasionally observed. However, they are far less visible compared to the combination of Arabic-English signs accounting for less than 7% of the total bilingual and multilingual signs of the sample. The results suggest that Kuwait is chiefly a bilingual landscape consisting primarily of signs that use Arabic, English, or a combination of both. Other expatriate languages appear irregularly often displayed on the sign alongside Arabic or English.

Consequently, the value and influence of English are playing a significant role in increasing its visibility in the LL of Kuwait. This manifestation is observed in its prominence in the collected sample of signs, appearing in more than 70% of the signs in monolingual, bilingual and multilingual forms. Other languages in the LL of Kuwait, usually catering to some of the most prominent groups of foreign expatriate nationalities such as Indians, Bangladeshis, Filipinos, Sri Lankans, and Pakistanis appear occasionally. However, since these non-Arab expatriate groups constitute almost half of Kuwait's population, they appear to be weakly represented in the LL appearing in just over 7% of the sample size.

The study further examines the main shopping streets in the six governorates of Kuwait as a geographic marker to determine differences of language use in signs in each location. The results indicated a higher presence of bilingual signs in comparison to monolingual signs in Hawalli and Capital governorates while showing the contrary in Jahra and Mubarak Al-Kabeer. Farwaniya and Ahmadi governorates had similar numbers of monolingual and bilingual signs. Concerning monolingual signs, the use of Arabic is perceived more frequently than English in Farwaniya, Jahra and Mubarak Al-Kabeer governorates.

In Ahmadi and Hawalli governorates, on the other hand, the use of both Arabic and English monolingual signs is regarded in practically identical numbers. Appearance of English monolingual signs is higher compared to Arabic monolingual in the Capital governorate. Moreover, it appears that the majority of signs containing languages other than Arabic and English appear in the Capital and Farwaniya governorates. Contrarily, higher number of Arabic monolingual signs is spotted to the expense of other sign types in Jahra and Mubarak Al-Kabeer. Consequently, the results correlate with the general characteristics of these governorates. The Capital and Hawalli governorates both have a distinct cosmopolitan and global flair, specifically in their main shopping areas. Thus higher English and expatriate language presence is perceived compared to other governorates. Farwaniya and Ahmadi governorates are urban metropolitan areas, densely populated by a large number of multinational and Arab expatriates. These characteristics may explain the even distribution of Arabic and English signs in those governorates. Jahra and Mubarak Al-Kabeer on the other hand, are typically suburban with many of their main shopping areas being close to suburban Kuwaiti houses. The expected assumption is that many of the sign posters in those areas create their signs based on similar signs in the same area. Much like the findings of Wenzel sign makers frequently resort to following the general habits and customs of the area by imitating the presentation of other local signs.

Conclusion & Limitations

Overall, the findings conclude that the majority of the LL in Kuwait included bilingual advertisements, with the majority using the English language, and that there were differences amongst the six different governorates. We interpret these findings in the LL of Kuwait as a reflection of the steady changes that are happening locally and regionally. The study was initially approached with the impression that English will feature significantly in the LL of Kuwait.

English has colonial, political, and business connections that began more than a century ago, and its significance in Kuwait is continually growing. The growth of English usage is seen in education, culture, and business, and its visual presence in the findings had exceeded any initial expectations for the study. Researchers who are considering conducting research in the field of linguistic landscapes can struggle to find a set of standardized set of established research tools. Differing goals and locations can present a setback in selecting appropriate methodologies that is successful in every LL research. For this study, the chosen framework and methodologies are a combination of borrowed, modified and newly developed approaches. While caution and careful consideration in selecting these methods, they can be tricky and problematic to apply in the real world. They produce a host of situations and conditions that require sacrifices, particularly those related to the primary language of branding and code preference. Moreover, the size of the sample of signs collected (2204 signs) reminds us that the findings of the study are generalizations based on a limited sample size. Additionally, the lack of any LL studies in Kuwait, or anywhere in the Gulf countries, for that matter, deny the ability for a direct comparison of results with other similar studies (Kaynak & Herbig, 2014).

Future Research

Researchers who are considering conducting research in the field of linguistic landscapes can struggle to find a set of standardized set of established research tools. Differing goals and locations can present a setback in selecting appropriate methodologies that is successful in every LL research. For this study, the chosen framework and methodologies are a combination of borrowed, modified and newly developed approaches. While caution and careful consideration in selecting these methods, they can be tricky and problematic to apply in the real world. They produce a host of situations and conditions that require sacrifices, particularly those related to the primary language of branding and code preference. Moreover, the size of the sample of signs collected (2204 signs) reminds us that the findings of the study are generalizations based on a limited sample size. Additionally, the lack of any LL studies in Kuwait, or anywhere in the Gulf countries, for that matter, deny the ability for a direct comparison of results with other similar studies.

In fact, with the exception of Israel, Jordan, and Yemen, there is a clear lack of linguistic landscape studies in the Middle East. Accordingly, the significance of this study is to contribute to the development of the LL field in a vastly unexplored region. Future LL research in Kuwait may be further investigated from a diachronic or layering perspective. These methods would allow comparisons and analysis of how the LL is changing in the future. Additionally, exploring indoor locations such as malls, universities, ministries, and hospitals, as well as movable signs all represent a fertile area of LL research that is not covered in this study. The potential of LL research in Kuwait and the rest of the Middle East permit an open door for pursuing a further investigation in this growing area of research.

References

Al-Athwary, A.A. (2017). English and Arabic inscriptions in the linguistic landscape of Yemen: A multilingual writing approach.International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature,6(4), 149-162.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alomoush, O.I.S. (2016, May). Top-Down and Bottom-Up Linguistic Layering in The Linguistic Landscape: The Case of Jordan. In5th International Conference on Language Education and Innovation.

Aristova, N. (2016). Rethinking Cultural Identities in the Context of Globalization: Linguistic Landscape of Kazan, Russia, as an Emerging Global City. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 236.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Backhaus, P. (2007). Linguistic landscapes. InLinguistic Landscapes. Multilingual Matters.

Blommaert, J. (2013).Ethnography, superdiversity and linguistic landscapes: Chronicles of complexity. Multilingual Matters, 18.

Bruyel-Olmedo, A., & Juan-Garau, M. (2015). Minority languages in the linguistic landscape of tourism: the case of Catalan in Mallorca.Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development,36(6), 598-619.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bulmer, S., & Buchanan-Oliver, M. (2006). Advertising across cultures: Interpretations of visually complex advertising.Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising,28(1), 57-71.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Caldwell, D. (2017). Printed t-shirts in the linguistic landscape: A reading from functional linguistics.Linguistic Landscape,3(2), 122-148.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Coluzzi, P. (2016). The linguistic landscape of Brunei.World Englishes,35(4), 497-508.

Dharma Keerthi, G.D., & Ranjan, S. (2010). Science of Semiotic Usage in Advertisements and Consumer’s Perception. Journal of American Science, 6(2), 6–11.

Dressler, R. (2015). Sign geist: Promoting bilingualism through the linguistic landscape of school signage.International Journal of Multilingualism,12(1), 128-145.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gorter, D. (2006). Introduction: The study of the linguistic landscape as a new approach to multilingualism.International Journal of Multilingualism,3(1), 1-6.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gorter, D. (2018). Linguistic landscapes and trends in the study of schoolscapes.Linguistics and Education,44, 80-85.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hiippala, T., Hausmann, A., Tenkanen, H., & Toivonen, T. (2019). Exploring the linguistic landscape of geotagged social media content in urban environments.Digital Scholarship in the Humanities,34(2), 290-309.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Inoue, F. (2005). Econolinguistic aspects of multilingual signs in Japan.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kachru, B.B. (1982). The bilingual’s linguistic repertoire. Issues in International Bilingual Education. 25-52.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kallen, J.L., & Ní Dhonnacha, E. (2010). Language and inter-language in urban Irish and Japanese linguistic landscapes.Linguistic Landscape in the City, 19-36.

Kaynak, E., & Herbig, P. (2014).Handbook of cross-cultural marketing. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kellerman, A. (2010). Mobile broad band services and the availability of instant access to cyberspace.Environment and Planning A,42(12), 2990-3005.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kivenzor, G.J. (2018). Why cross-cultural issues in management and marketing are that important and worth our undivided attention?.Journal of Management and Training for Industries,5(3), 1-12.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Laihonen, P. (2016). Beware of the dog! Private linguistic landscapes in two ‘Hungarian’villages in South-West Slovakia.Language Policy,15(4), 373-391.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Landry, R., & Bourhis, R.Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality: An empirical study.Journal of Language and Social Psychology,16(1), 23-49.

Lee, H.S., & Lopetcharat, K. (2017). Effect of culture on sensory and consumer research: Asian perspectives.Current Opinion in Food Science,15, 22-29.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lou, J.J. (2010). Chinese on the side: The marginalization of Chinese in the linguistic and social landscapes of Chinatown in Washington, DC.Linguistic Landscape in the City, 96-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nash, D. (2013). Wind direction words in the Sydney language: A case study in semantic reconstitution.Australian Journal of Linguistics,33(1), 51-75.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nikolaou, A. (2017). Mapping the linguistic landscape of Athens: The case of shop signs.International Journal of Multilingualism,14(2), 160-182.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Piller, I. (2001). Identity constructions in multilingual advertising.Language in Society,30(2), 153-186.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Scollon, R., & Scollon, S.W. (2003).Discourses in place: Language in the material world. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Someya, H. (2002). Kanban no moji hyoki [Letters on signs].Gendai Nihongo Koza [Modern Japanese Course],6, 221Á243.

Stephen Gossett. (2022). Exploring Semiotics in Marketing. BuiltIn.

Takhtarova, S.S., Kalegina, T.E., & Yarullina, F.I. (2015). The role of English in shaping the linguistic landscape of Paris, Berlin and Kazan.Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,199, 453-458.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Troyer, R.A., & Szabó, T.P. (2017). Representation and videography in linguistic landscape studies.Linguistic Landscape,3(1), 56-77.

Verdenhofs, A., & Tambovceva, T. (2019). Evolution of customer segmentation in the era of big data.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 14-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. JMIDS-22-12680; Editor assigned: 15-Oct-2022, PreQC No. JMIDS-22-12680(PQ); Reviewed: 28-Oct-2022, QC No. JMIDS-22-12680; Published: 31-Oct-2022