Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 5

Exploratory model of commuting habitus in the COVID-19 era

Elias Alexander Vallejo Montoya, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Cruz Garcia Lirios, Autonomous University of the State of Mexico

Diego Leon Restrepo Lopez, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Hector Enrique Urzola Berrio, University of Antonio José de Sucre Corporation

Clara Judith Brito Carrillo, University of La Guajira

Citation Information: Montoya, E.A.V., Lirios, C.G., Lopez, D.L.R., Berrio, H.E.U., & Carrillo, C.J.B. (2022). Exploratory Model of Commuting Habitus in the Covid-19 Era. Journal of International Business Research, 21(5), 1-12.

Abstract

The transfer habitus explains the expectations, needs and preferences of users to carry out a journey from the choice of a destination. In the COVID-19 era, the habitus was modified, but to what extent is unknown. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore the relationships between the transfer habitus and the variables reported in the literature. A cross-sectional, exploratory and psychometric study was carried out with a sample of 100 students from a public university in central Mexico, considering their degree of exposure to risks in public transport. A four-dimensional factorial structure was found that explained the transfer habitus. In relation to the state of the question, the extension of the proposed model is discussed.

Keywords

COVID-19, Habitus, Transport, Suburban, City, Security.

Introduction

Until July 2022, the pandemic has directly and indirectly claimed the lives of around five million people in the world and one million in Mexico, although underreporting is recognized that could increase the figure (Bustos et al., 2021). In this context of risk, the mitigation and containment policies for Covid-19 have focused on distancing and confinement strategies, but only in the first months, since the communication and management of the crisis has been the recommendation of healthy distance. This strategy is related to habitus because it translates as negotiation, agreement and co-responsibility between the parties involved.

A communication of the pandemic that promotes distancing involves the mass transportation system (Quiroz et al., 2020). On the one hand, it impacts the user's decisions to reduce their mobility. On the other hand, it schedules its decisions based on costs and benefits. The transport user can run the risk of traveling in the public system, although he can calculate the differences with respect to a car transport. Or, the user chooses to delete their mobility plans, even when working or studying.

In any scenario, the decision is prospective. That is, the costs outweigh the benefits, but it is these risks that generate more benefits in a context of risk aversion. In this way, prolonged negotiation, consensus and responsibility are associated with irregular communication of risks (Salvatore, 2020). In the case of the Mexican government, its communication can be considered irregular if the statements of its president and health officials are considered (Casilli, 2019). Until May 2020, the Mexican State presumed that it had the pandemic under control, but the cases increased in June.

However, citizens refrained from transporting and vacationing. It was until the end of December when the pandemic reached its peak of contagion, but without the hope of the vaccines promoted by the government (Chapain & Sagot, 2020). The public reacted with mobility just above the average of previous years. In this period, the habitus or negotiation between the parties was observable in the agglomeration of foreign transport. Also, in the provision of food or solidarity such as courtesy trips in taxis. The use of mobile phones to stay informed was another indicator, as well as the commitment to use face masks.

Thus arose a disposition in favor of mass transport. At the same time, there was an underlying agreement between users and authorities to respect the boarding and alighting of public transport (Aspilla et al., 2016; Bedoya et al., 2016). Along the same lines, research on the impact of the pandemic on mass transportation suggests that overcrowding determines the probability of contagion. Ventilation in transport explains the cases of contagion in regular subway users.

In the case of tourist transport, the image of the destination, like biosecurity, is the predictor of the transfer decision (Nava & Mercado, 2019). Staff training is another factor that refers to biosafety as an added value of accommodation. The sum of the biosafety and training protocols affect the tourist's stay, but it is the transfer time and the quality of the service that defines the destination.

Bourdieu (1979) defines the habitus as: "a system of lasting and transferable dispositions that integrate all past experiences and functions at all times as a structuring matrix of the perceptions, evaluations and actions of the agents in the face of a situation or event." The concept of habitus refers to a setting that interacts with a system of dispositions. The pandemic is a determining juncture of expectations, but it is also the product of the internalization of data regarding infections, diseases and deaths. In relation to public transport, the transport habitus is the result of the association between confinement and mobility policies with respect to the selfconcept of health.

Habitus cultivated as features of the influence of structures on personal criteria reveal possible practices. Cultivated habitus, symbolic capitals, and fields of interaction anticipate practical meaning (Bourdieu, 1979). Mobility and personal transfer as a practical sense is the result of habitus, capitals and fields. The pandemic as a situation anticipates a practical sense. The prevention of COVID-19 in transportation suggests a translation of the information from the environment in the media together with the capitals and fields. Transport safety symbols along with interaction scenarios predict a practical sense of destination image.

The habitus generates an enclosure that is appreciated in the practices (Bourdieu, 1979). This system of prioritization of practices based on the provisions to objectify information on the pandemic explains transfer preferences and destination choices. The use of public transport to be defined by the cultivated habitus reflects the differences between users in terms of budget, conservation and satisfaction. In this sense, the pandemic is a situation that allowed the emergence of a habitus, the subsequent practicality and the classification of the type of transfer.

The relationship between habitus and praxis allows us to appreciate the classifications of a social group (Bourdieu, 1990). The pandemic revealed the habitus and the practice of confinement and detachment characteristic of social groups that have avoided contact with other sectors. Public transport revealed a risk classification by users who considered their work as essential compared to jobs that are considered secondary. The praxis reflects the differences between social strata. The praxis of transfer explains the differences between the habitus of users who share public transport.

Class habitus acquire a computational programming meaning by explaining the inheritance of disposition (Bourdieu, 1990). In this sense, the pandemic and the risk of contagion in public transport reveal the class habitus and the meaning of preventive praxis. In addition, the classification of COVID-19 as a potential risk for vulnerable sectors explains the use of auto transport or preferential transfer.

The practical sense allows us to appreciate the habitus as a transition from emergent subjectivity to structured objectivity (Bourdieu, 2007). The class habitus reflects the differences between groups, sectors and strata, but its hereditary and transferable condition anticipates its reproduction. The habitus can be observed in principles and practices, even if it is only a pragmatic and volatile convention. Indeed, habitus is an unforeseen, indefinite, inexorable and intermittent practice. Precisely, the pandemic generated discontinuous policies with the habitus of the academic communities. Public transport was the scene of a habitus devoid of the epidemiological traffic light. The social communication of the State recommended the confinement, but the habitus of transfer in the student communities guided only a preventive use.

The pragmatic habitus as the will to negotiate mobility and transfer and permanence spaces converges with the traditional definition. If the cultivated habitus is related to praxis as a reflection of a practical class sense, the transfer habitus implies an internalization of risks. Students who travel by public transport negotiate their safety and health with their authorities. A favorable disposition to confinement limits mobility and movement, although it prevents risks of contagion, illness and death.

The traditional habitus that derives from objective class differences and the surrounding information about a situation is different from the transfer habitus that implies concertation. The traditional habitus inhibits state communication and contagion expectations. The habitus of transfer is the use of a mask by public transport rule and by the internalization of specialized conferences. The traditional habitus inhibits the relocation habitus.

The habitus is a negotiation between the interested parties in their relations of symbolic equity (Sanchez et al., 2022). It is an exchange of imaginaries and representations around a social process. In the case of public transport, the habitus is seen in the relationship between transport supply and demand. Thus, those who choose a high-risk option such as collective transport on secondary roads reflect a propensity for risk. In contrast, those who choose a transfer from an airplane are inclined to be risk adverse (Aldana et al., 2020). Consequently, the determinants of risk aversion or propensity emerge from a balance between costs and benefits of relocation. That is, those who travel to a tourist destination choose their type of transfer according to a calculation of profits and losses (Hernandez et al., 2021). This is how those who choose high-risk transport expect high profits. On the contrary, those who choose a safer and less risky transport anticipate a scenario of low profitability.

Relocation habits, being conditioned by this logic of costs and benefits, reach a decision process that seeks a balance between the demands of the environment and the internal resources available (Garcia et al., 2021a). Tourism is a phenomenon of decisions that imply losses and gains. In the case of choosing a tourist destination, the transfer is a determining factor (Bustos et al., 2020). If travel habits are based on risk aversion, the choice of tourist destination will be systematically repeated (Sandoval et al., 2021). On the contrary, if travel habits correspond to a propensity for risk, then the selected tourist destination will vary according to the balance between costs and benefits.

Within the framework of the habitus of aversion or propensity to transfer risk, the transfer time is a determining factor in the choice of the tourist destination and its unsystematic or systematic repetition (Garcia, 2021). If the transfer generated by an aversion to risk and the transfer time is long, the choice of the tourist destination will probably not be repeated (Garcia et al., 2020 & 2021b). Short travel time is related to risk aversion habitus in the probable choice of a tourist destination (Molina et al., 2021). Regarding the propensity for risk, both short and long travel times affect the non-repetition of a destination.

The traditional habitus, by circumventing transport regulations and the image of the destination, diversifies into transfer habitus. The transfer habitus can be seen from aesthetics (aesthesis), logic (eidos), ethics (ethos), and expressiveness (hexis).

Based on the transfer habitus theory, studies in this regard have established four dimensions: aesthesis, ethos, eidos, and hexis (Garza et al., 2021). The aesthetic transfer habitus (aesthesis) correspond to the choice of cultural tourist destinations (Carreon et al., 2020). In the selection of a tourist destination, the logical transfer habits (eidos) are associated with the supply of science and technology (Guillen et al., 2021). Ceremonial and religious centers are associated with the habitus of ethical transfer (ethos). In his case, preferences for moving to creative cities are determined by the habitus of expressiveness (hexis).

The development of instruments that measure travel habits based on the aesthetic, logical, ethical or expressive appeal of a destination allowed for the diversification of explanatory models (Perez et al., 2021). These are the cases of the variables of agglomeration, food, civility, connectivity and commitment to tourist services as added values to the image of the destination. Agglomeration had already been proposed as a determining factor of transport habitus and risk aversion in collective transport (Juarez et al., 2020). In cases where the transfer is prolonged, food and Internet service are determining factors in choosing the type of transport and destination. In cases of risk prevention due to Covid-19, civility is a factor that conditions the choice of transport with proximity (Quintero et al., 2021). Finally, when users identify the transport driver as expert and responsible, they approach risk aversion.

From the traditional habitus, a model is a provisional explanation of the relationships between aesthetics (aesthesis), logic (eidos), ethics (ethos), and expressiveness (hexis). The model reveals the traditional habitus from its transfer indicators in a situation of confinement and social distancing.

A model is a strategic representation of the contrast between the findings reported in the literature regarding proposals to address a problem. In the case of the image of the destination as a variable determined by the context, type of transport and travel time, the model includes the possible relationships between the categories (Alvarado et al., 2021). In this way, the hypotheses that support the contrast of the model warn that the context of transfer: agglomeration, food, civility, cyber use and commitment is different in samples that present habitus of aversion and propensity to risk. Consequently, the relationship between the variables of the transfer context will determine the choice of the type of transport and tourist destination (Quiroz et al., 2020). The transfer context is a stay that competes with the type of destination. Even the transfer context is an added value of the image of the destination (Rincon et al., 2021). They are travel, stay and return expectations that the user of transport and tourism services adds to the image of the destination.

Are there significant differences between the dimensions of agglomeration, food, civility, cyber use and commitment around tourist mobility with respect to the observations made in this study?

The premises that guide this work suggest that there are differences between the dimensions reported in the literature in terms of observations. The risk communication of the Mexican government has fostered a tourism habitus that is rooted in negotiation, agreements and co-responsibilities. These are the cases of tourists who, given the recommendation of distancing and confinement, congregate in mass transport (Sapiro, 2019). Or, the cases in which the State disseminates the supply of resources, but users look for food outside their nearby shopping center. Similarly, given distancing recommendations, users give up their places or taxi drivers offer their services free of charge. All these indicators converge in a disposition against or in favor of managing the pandemic. Such relationships between indicators and factors would explain the effect of pandemic communication on travel decisions for recreational purposes.

Method

Design a non-experimental, exploratory and cross-sectional study was carried out. Studies explaining the effect of the media on decision making and behavior have focused on agenda setting. It is about establishing the axes and themes related to a topic that is spread by the media to influence public opinion (Bedolla et al., 2016). The contrast of this agenda with the habitus would allow us to anticipate an impact scenario. In the case of public transport, risk communication, by establishing distance and confinement as axes, generated a transversal axis. As the risks intensify, transport users create crowds. Therefore, the measurement of the cross section is relevant.

Sample An election of 100 students (M=20 years, SD=0.36). The inclusion criterion was about the journey in hours from home to school (M=2.46 hrs and SD=0.30 minutes). Return from campus to home (M=2.00 hrs and SD=0.70 minutes). The inclusion criteria were having monitored the presidential conferences on the coronavirus, as well as having listened to the distancing and confinement strategies of the people. The use of public transport for vacations, even when they have access to auto transport. In the case of income, a factor for choosing the destination, the average was 1,781.89 USD per month.

Instrument The Periurban Mobility Habitus Inventory was used, which contains 30 indicators. It includes five response options ranging from “doesn't look like my situation” to “looks a lot like my situation”. The first version proposes four dimensions alluding to the break, the trip, the stay and the return, but as they are general they do not sufficiently explain decisionmaking. The more recent version of aesthesis (aesthetics), ethos (ethics), hexis (logic) and eidos (experience) obtained greater consistency, but its generality could not anticipate transfer options. Both versions reached consistencies above the essential minimums, but only when they were associated as determinants of the transfer decision (Olague et al., 2017). Therefore, the exploration of the dimensions related to habitus as a negotiation will allow us to explain the phenomenon.

Process The sample was contacted by institutional mail. An interview was requested and the academic and institutional purposes of monitoring the graduates were reported. Once the appointment was established, a questionnaire was delivered that included sociodemographic, economic, and organizational psychological questions. In the cases in which there was a tendency to the same response option or the absence of a response, they were asked to write on the back the reasons why they answered with the same response option or, where appropriate, the absence of the same. The data was captured in the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) and the analysis of structural equations was estimated with the help of the Analysis of Structural Moments (AMOS) version 18 program.

Analysis The establishment of the structural model of reflexive relationships was carried out considering the normality, reliability and validity of the scale that weighted the psychological construct. The kurtosis parameter was used to establish the normality of the distribution of responses at the level of commitment questioned. The results show that the kurtosis parameter had a value less than eight, which is the minimum, suggested to assume the normality of the distribution. In the case of reliability, Cronbach's alpha value allowed establishing the relationship between each question and the scale. A value greater than 0.70 was considered as evidence of internal consistency. Finally, the exploratory factorial analysis of main axes and promax rotation in which factorial weights greater than 0.300 made it possible to deduce the emergence of commitment from eight indicators.

Results

Table 1 shows the values of the normal distribution that suggest a factor analysis. That is, the consistency of the instrument can be observed in other samples. In addition, it refers to five dimensions related to agglomerations, food, civility, cyber use and loyalty to transport. In other words, the habitus as transfer provisions in the face of the news of the pandemic are configured by the five established factors. The instrument distinguishes five types of travel habitus: agglomeration, food, civility, cyber use and commitment. Each of the five factors suggests that traditional habitus determines relocation expectations. The relationship between the five factors made it possible to reveal the expectations that arise in the face of anti-COVID policies.

| Table 1 Reliability And Construct Validity |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | Indicator | M | SD | Α | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 |

| r1 | I often meet so many people on the subway | 3.45 | 0.95 | 0.701 | 0.374 | - | |||

| r2 | I try to get on the minibus, even if it reaches its maximum capacity | 3.47 | 0.83 | 0.732 | 0.384 | - | - | - | - |

| r3 | I use zero-emission transport, even if it circulates at its maximum capacity | 3.29 | 0.81 | 0.705 | 0.389 | - | - | - | - |

| r4 | I share the taxi with the people who fit | 3.05 | 0.96 | 0.793 | 0.301 | - | - | - | - |

| r5 | I often go to eat on the way to my destination. | 3.85 | 0.74 | 0.739 | 0.304 | - | - | - | - |

| r6 | I try to buy a product to eat on the minibus. | 307 | 0.95 | 0.705 | 0.394 | - | - | - | - |

| r7 | I eat food while sitting on the bus. | 3.71 | 0.85 | 0.738 | 0.312 | - | - | ||

| r8 | When the transport allows the sale, I usually buy something to eat | 3.72 | 0.96 | 0.752 | - | 0.385 | - | - | - |

| r9 | I usually respect small spaces for people with different abilities | 3.00 | 0.39 | 0.753 | - | 0.391 | - | - | - |

| r10 | I avoid invading the seats of the elderly | 3.08 | 0.84 | 0.729 | - | 0.384 | - | - | - |

| r11 | I collaborate in the identification of missing persons in the subway | 3.04 | 0.59 | 0.715 | - | 0.336 | - | - | - |

| r12 | I help people who ask me to reach their destination | 3.01 | 0.51 | 0.703 | - | 0.316 | - | - | - |

| r13 | When I see an elderly person standing up, I usually offer them my seat. | 3.49 | 0.48 | 0.739 | - | - | 0.388 | - | - |

| r14 | On the subway I usually make sure that seats for the elderly are respected | 3.36 | 0.36 | 0.734 | - | - | 0.345 | - | - |

| r15 | I avoid boarding transport confined to women | 3.14 | 0.85 | 0.704 | - | - | 0.315 | - | - |

| r16 | I usually pay transportation to people who ask for help. | 3.26 | 0.94 | 0.772 | - | - | 0.367 | - | - |

| r17 | I check my email while I arrive at my destination | 3.15 | 0.25 | 0.712 | - | - | 0.376 | - | - |

| r18 | I use the subway network to check my emails | 3.04 | 0.36 | 0.735 | - | - | 0.366 | - | - |

| r19 | I help Internet users on the subway | 3.72 | 0.46 | 0.789 | - | - | - | 0.341 | - |

| r20 | I request that cyber users of the metro respect the allotted time | 3.26 | 0.61 | 0.793 | - | - | - | 0.346 | - |

| r21 | I've waited for the subway until I found a free seat | 3.49 | 0.58 | 0.734 | - | - | - | 0.342 | - |

| r22 | I have taken the bus from the base to the destination. | 3.05 | 0.84 | 0.715 | - | - | - | 0.326 | - |

| r23 | I have traveled in the minibus until late at night. | 3.84 | 0.91 | 0.725 | - | - | - | 0.346 | - |

| r24 | I have waited for public transport before it starts to circulate | 3.31 | 0.88 | 0.730 | - | - | - | 0.332 | - |

| r25 | As I ride the subway, I review my class notes | 3.20 | 0.95 | 0.748 | - | - | - | - | 0.326 |

| r26 | I prepare for exams on the way to school. | 3.22 | 0.89 | 0.778 | - | - | - | - | 0.384 |

| r27 | I do my homework on the subway | 3.04 | 0.97 | 0.792 | - | - | - | - | 0.331 |

| r28 | I do my homework during my trip in the minibus. | 3.64 | 0.95 | 0.736 | - | - | - | - | 0.368 |

| r29 | My sense of punctuality forces me to take different routes to arrive on time | 3.46 | 0.89 | 0.715 | - | - | - | - | 0.346 |

| r30 | My schedule of activities allows me to travel on different routes | 3.15 | 0.88 | 0.782 | - | - | - | - | 0.306 |

|

Source: Prepared with study data; M = Mean, SD=Standard Deviation, A=Value element excluded from the alpha value, C=Kurtosis (1.294); p=0.000; F1=Agglomeration (28% of the variance, alpha=0.721), F2=Food (25% of the variance, alpha=0.739), F3=Citizenship (23% of the variance, alpha=0.758), F4=Cyberuse (14 % of the variance, alpha=0.794), F5=Commitments (10% of the variance, alpha=0.745). KMO=0.682; [X2=14.25 (12 df ) p=0.000] |

|||||||||

The results can be interpreted from the traditional habitus theory. Each of the five factors reflects a relocation habitus that differs from the traditional habitus. The traditional habitus suggests that each factor is defined by the health emergency as a disposition, but not as a practice. The transfer habitus establishes that each factor is the product of negotiation between the authorities and the users of public transport.

The agglomeration factor in transport is distant from the transport habitus and close to the traditional habitus. The feeding factor in transport suggests closeness to the transport habitus and a distance from the traditional habitus. The civility factor is attached to the habitus of transfer and away from the traditional habitus. The cyberuse factor moves away from the traditional habitus and approaches the habitus of transfer. The commitment factor in risk prevention is close to the transfer habitus and far from the traditional habitus.

Once the structure of factors and indicators that explain the habitus as a negotiation between political and civil actors was established, the relationships between these factors were estimated to observe a common agenda Table 2. This is so because the convergence of the five factors would allow us to appreciate the configuration of a theme structure. This is the case of the communication of the pandemic and its influence on transfer decisions in the sample surveyed

| Table 2 Covariance Relationships Between Factors |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | |

| F1 | 24.32 | 13.24 | 1,000 | - | - | - | - | 0.916 | - | - | - | |

| F2 | 22.45 | 15.46 | 0.432* | 1,000 | - | - | - | 0.555 | 0.906 | - | - | - |

| F3 | 21.26 | 18.43 | 0.325** | 0.431*** | 1,000 | - | - | 0.000 | 0.676 | 0.991 | - | - |

| F4 | 20.43 | 14.35 | 0.542* | 0.326* | 0.438* | 1,000 | - | 0.098 | 0.104 | 0.170 | 0.995 | - |

| F5 | 25.47 | 16.20 | 0.439*** | 0.437* | 0.541* | 0.631* | 1,000 | 0.125 | 0.252 | 0.328 | 0.005 | 0.903 |

| Source: Prepared with data study; F1=Agglomeration, F2=Food, F3=Civility, F4=Cyberuse, F5 =Commitments; * p<0.01; ** p<0.001; *** p<0.0001 | ||||||||||||

The five factors are close to the policies, strategies and programs of the State. Each of the five factors is adjusted to the distancing and confinement that the government promotes in media and social networks. The structure of the five factors and their indicators suggests that the State determines a transfer habitus, influencing the traditional habitus.

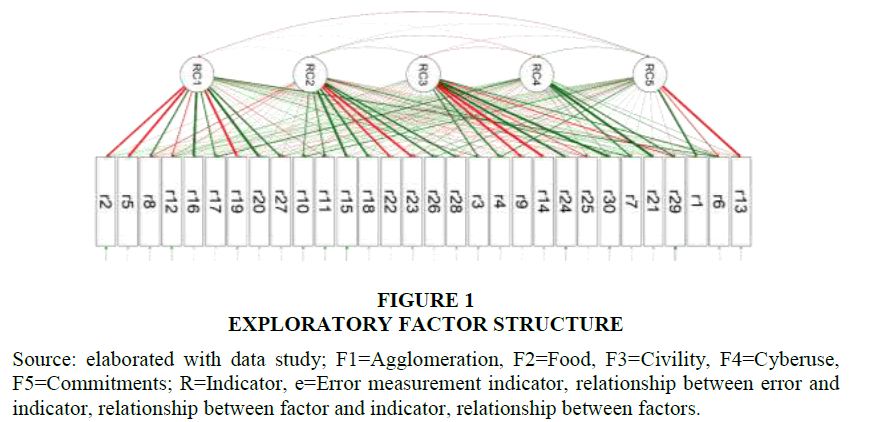

The factorial structure suggests a more complex structure with these five factors and thirty indicators. Both make up a tourist habitus as a provision in the face of the pandemic. Consequently, in the face of tourism promotion policies, but with a recommendation of distancing, the surveyed sample tends to decide on the agglomeration. This means that risk communication creates counterproductive provisions. To corroborate the assumption of differences between the theoretical factors with respect to the exposed findings, a model was contrasted Figure 1. This exercise made it possible to establish the agenda as a scenario of risks and habitus. It then means that transportation is a space of disobedience because exposure to risks exposes more agglomeration than needs for food, civility, cyber use or commitment.

Figure 1: Exploratory Factor Structure.

Source: elaborated with data study; F1=Agglomeration, F2=Food, F3=Civility, F4=Cyberuse, F5=Commitments; R=Indicator, e=Error measurement indicator, relationship between error and indicator, relationship between factor and indicator, relationship between factors.

The fit parameters and residuals [χ2=12.23 (13 df) p>0.05; GFI=0.990; IFC=0.997; RMSEA=0.007] suggest the non-rejection of the null hypothesis. The hypothesis test suggests that the literature has reported a habitus structure similar to the established model. The nonrejection of the null hypothesis shows that government communication of risks in public transport has minimized the traditional habitus and increased the habitus of transport. In other words, the differences between the dimensions reported in the literature and the study findings seem to coincide in a common agenda. This is so because risk communication has such coverage that it fosters despair. In other words, if the State only recommends distancing, confinement or the use of masks without having sufficient detection tests, treatments or vaccines, then the sample surveyed responds with the intention of agglomeration and risk behaviors.

Discussion

The contribution of this work to the state of the question lies in the measurement of the habitus in the face of the communication of the pandemic. It is a model of five factors and thirty indicators. It is a structure that suggests a probable agglomeration in the face of distancing and confinement. In this sense, it is convenient to consider habitus as dispositions to agglomeration. This social disobedience in the face of the communication of the pandemic is the beginning of a State-society relationship (Gauna, 2017). The literature has reported the formation of these habitus as responses to the distance and confinement promoted.

This is the case of the stigma against carriers of Covid-19. The State suggests distancing but given the social stigma of doctors as carriers of the coronavirus, it is insufficient. This means that the pandemic generates an inconsistent strategy. The effect of this policy on tourism is ambivalent (Khasimah et al., 2016). On the one hand, it creates hopelessness, but at the same time it encourages exposure to risk. Given that governments follow the confinement and distancing protocol, this work will contribute to the modification of said strategy.

Before the pandemic, the prediction of the tourist destination was established from its image. If a tourist selected a place, then it was documented about it. The arrival of the coronavirus changed that pattern. However, biosafety is a determining factor in the image of the destination. The tourist chooses advertising on sanitation. Such biosecurity would not be possible without the habitus of the tourist (Martínez, 2017). Provisions in favor of sanitation would explain the choice of accommodation.

Habitus theory, which notes class differences reflecting the diversification of the transfer, the present work demonstrated five practical dimensions: agglomeration, food, civility, cyber use and commitment. Agglomeration is a provision of the transfer habitus that defies the confinement policy, but its association with civility reveals an aversion to the risks of contagion. Food consumption on public transport reflects the class habitus. The use of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram or WhatsApp in public transport conforms to the habitus of the Internet user class. The commitment to responsible transportation through the use of a mask and distancing contravenes the traditional habitus. The respondents show a habitus of movement that is related to the traditional habitus in terms of biosecurity. The prevention of risks of contagion, disease and death contravenes the class habitus that makes those without resources vulnerable. The pandemic revealed the class habitus and the transfer habitus. Public transport in a pandemic context revealed a travel habitus that explains why respondents crowd together.

Conclusion

The objective of this work was to compare the dimensions of the habitus against the pandemic. Five factors found explain social disobedience in the face of the communication of the pandemic. The surveyed sample presented a habitus that consists of the disposition before the coronavirus and their vacations. These are provisions for crowding, nutrition, citizenship, cyber use, and participation. Each factor explains the habitus that emerges from the spread of confinement and distancing, as well as preventive measures. The surveyed sample systematically disobeys the promotion of tourism based on the risks of contagion.

In relation to the theory of traditional habitus, which posits that the dispositions towards a conjuncture oscillate between the information disseminated by the State and the expectations of the individual, this work warns of a diversification of factors: agglomeration, food, civility, cyber use and commitment. Each factor explained a percentage of the variance of the habitus observed in the surveyed sample. The agglomeration factor in response to confinement and social distancing policies explained the greater variance of the transfer habitus. The traditional habitus differed from the transfer habitus in relation to mobility policies and public transport. The traditional habitus distances itself from the epidemiological traffic light and risk prevention. The transport habitus adheres to the biosafety protocol for public transport users.

In relation to the theory of transfer habitus, which highlights the relationship between risk aversion and propensity with respect to the choice of destination, this paper warns that the transfer context is made up of five preponderant factors. In this sense, the differences between the structures of findings reported in the literature with respect to the established model, both explain the importance of the transfer context. Lines of research related to the context of stay and return will make it possible to anticipate risk aversion and propensity scenarios around the choice of transport and destination preference.

Regarding the studies of the transfer habitus where four dimensions related to expressiveness, logic, aesthetics and ethics stand out, the present work warns that a structure of the transfer context can be explanatory of the differences between these dimensions. It is a context in which the dimensions become relevant considering the effects of Covid-19 on the decisions of transfer, stay and return of tourists. Therefore, the investigations oriented to the empirical demonstration of the transference dimensions will complement the results of the present study where the structure of the transference context was established. Themes, context and dimensions of the transfer will allow us to explain and anticipate scenarios of risk aversion or propensity in the face of decisions to stay and return.

Regarding the empirical evidence of the modeling of the transport context, where the relationships between the factors of agglomeration, food, civility, cyber use and commitment as determinants of the type of destination are highlighted, the present work suggests that context indicators can anticipate the transfer destination type This is so because the relationship between the transfer type and the destination image is ongoing. Therefore, the transfer context can help predict future destination choices, considering the reason for the stay. Studies related to the relationship between the determinants of transfer and stay will make it possible to generate biosafety policies that prevent risk scenarios.

References

Aldana, W.I., Sanchez, R. & Garcia, C. (2020). The structure of the perception of public insecurity. Tlatemoani, 34(1), 52-67.

Alvarado, S., Carreón-Guillén, J., & Garcia-Lirios, C. (2021). Modeling of the mobility habitus in the public transport system with low CO2 emission mechanics in the center of Mexico. Advances in Mechanics, 9(2), 82-95.

Aspilla, Y., Garcia, F., & Silva, M.R. (2016). Education for non-motorized mobility: university system of bicycle loan in internal mobility. Educational Sciences, 26 (48), 13-39.

Bedoya, V.R., Sardà, O.M., & Guasch, C.M. (2016). Estimación de las emisiones de CO2 desde la perspectiva de la demanda de transporte en Medellín. Transporte y Territorio, (15), 302-322.

Bourdieu, P. (1979). The distinction. Criteria and social bases of taste.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). Sociology and culture.

Bourdieu, P. (2007). The practical sense.

Bustos, J.M, Juarez, M., & Garcia, C. (2021). Validity of the habitus model of coffee entrepreneurship. Summa , 3 (1), 1-21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bustos, J.M, Juarez , M., Garcia , C., Sandoval, F. R. & Amemiya , M. (2020). Psychosocial determinants of the reactivation of tourism in the Covid-19 era. Tlatemoani, 28(1), 1-23.

Carreón, J., Bustos, J.M, Bermúdez, G., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2020). Attitudes towards the pandemic caused by the SARS CoV-2 coronavirus and Covid-19. Invunus, 15(2), 12-16.

Casilli , A. (2019). In the back room of artificial intelligence. An investigation on micro work platforms in France. Archus , 45, 85-108.

Chapain , C. & Sagot , D. (2020). Cultural and creative clusters: a systematic review of the literature and a renewed research agenda. Urban Research and Practice, 13(3), 300-329.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Garcia, C. (2021). Modeling of work commitment before Covid-19 in a public hospital in central Mexico. Medical Gazette, 44 (1), 34-40.

Garcia, C., Espinoza, F., Bustos, J.M, Juarez, M. & Sandoval, F.R (2021). Perceptions about entrepreneurship in the Covid-19 era. Critical Reason, 12 (1), 1-12.

Garcia, C., Juarez, M., Bustos, J.M, Sandoval F.R & Quiroz, C.Y (2020). Specification of a model for the study of perceived risk. Reget, 24 (43), 2-10.

Garza, JA, Hernandez, TJ, Carreon, J., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2021). Contrast of the determinants of the tourism permanence model in the Covid-19 era: Implications for biosafety. Tourism & Heritage, 16 (1), 11-21.

Gauna, C. (2017). Perception of the problem associated with tourism and the interest of the population in participating: Puerto Vallarta case. The Sustainable Journey, 33 (1), 251-290.

Hernandez, T.J, Carreon, J. & Garcia, C. (2021). Reengineering in the entrepreneurship of the coffee and tourism industry in central Mexico. Magazine Previews, 9(2), 63-81.

Juárez, M., Bustos, J.M., Carreón, J. & Garcia, C. (2020). The perception of risks in university students in the face of the spread of the SARS CoV-2 coronavirus and the Covid-19 disease. Journal of Psychology, 8(17), 94-108.

Khasimah , N., and Hashim , S., Mohd , S. T., and Harudin , S. (2016). Tourist satisfaction with a destination: an investigation of the visitor to Lanwaky Island. Tourism Journal of Marketing Studies, 8(3), 173-189.

Molina, M.R., Coronado, O., Garcia, C. & Quiroz, C.Y. (2021). Contrast a model of security perception in the Covid-19 era. Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 8(1), 77-83.

Nava, M. & Mercado, A. (2019). Governance networks in the tourist cluster of Mazatlan. Region and Society, 31(1), 1-22.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Olague J.T, Flores, CA & Garza, J.B (2017). The effect of travel motivation on tourist satisfaction through destination image dimensions. The case of urban leisure tourism in Monterrey, Mexico. Journal of Tourism Research, 14 (1), 119-129.

Pérez, M.I, Bustos, J.M, Juárez, M. & Garcia, C. (2021). Attitudes towards the effects of Covid-19 on the environment. Psychology Journal, 10(20), 9-30.

Quintero, M.L., Nava, S., Limón, G.A., Vélez, S.S. & Garcia, C. (2021). Subjective well-being in the era of Covid-19. Journal of South Asian Social Studies, 1(1), 38-49.

Quiroz, C.Y., Bustos, J.M., Juarez , M., Bolivar , E. & Garcia , C. (2020). Exploratory factorial structural model of perception of mobility in cycle paths. Purposes and Representations, 8(1), 1-14.

Rincon, R.M., Quiroz, C.Y., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2021). Contrast of a review of the entrepreneurship model in the Covid-19 era. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 1(2), 20-25.

Salvatore, K. (2020). Habitus mobility in the transport of zero emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Science and Research, 7 (2), 1-4.

Sanchez, A., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2022). Profusion and connectivity of coffee-growing entrepreneurship in the Covid-19 era. Managerial Vision, 21 (1), 1-8.

Sandoval, FR, Molina, HD & Garcia, C. (2021). Retrospective meta -analytic network of public transport and its effects on health governance. International Journal Advances in Social Sciences, 9(1), 8-18.

Sapiro, G. (2019). Rethinking the concept of autonomy for the sociology of symbolic goods. Symbolic goods, 4 (1), 1-51.

Received: 01-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. JIBR-22-12547; Editor assigned: 03-Sep-2022, Pre QC No. JIBR-22-12547(PQ); Reviewed: 16- Sep-2022, QC No. JIBR-22-12547; Revised: 23-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. JIBR-22-12547(R); Published: 30-Sep-2022