Research Article: 2018 Vol: 21 Issue: 1

Experiential Interdisciplinary Approach to Teaching: A Case of Collaboration Between Entrepreneuship And Media Production

Gulnara Z Karimova, SP Jain School of Global Management

Raina Rutti, Dalton State College

Abstract

Innovative teaching methodologies are widely used in institutions of higher education to increase students’ motivation and enhance learning outcomes. Interdisciplinary and experiential teaching are two of the innovative teaching formats. The interdisciplinary approach to education amalgamates two or more disciplines while experiential education provides opportunity to enact and apply theoretical concepts into practice. This study demonstrates how the combination of these two teaching methods can significantly enrich the educational experience of students. Using the example of Entrepreneurship and Print and Online Media Production courses, this paper illustrates how two faculty members can work together exposing students to the dynamic processes of the ‘real’ business world and complexity of business relations and communication.

Keywords

Experiential Education, Interdisciplinary, Entrepreneurship, Print and On-line Production, Marketing Communications.

Introduction

The interest in entrepreneurship education has been experiencing a significant growth. The literature in the areas of entrepreneurship education is brimming with examples of the application of interactive teaching techniques to entrepreneurship. The interdisciplinary (also called cross-disciplinary) (e.g. Levenburg, Lane & Schwarz, 2006) and experiential (also called action learning and situational learning) (e.g. Berbegal-Mirabent, Gil-Doménech & Alegre, 2016; Cooper, Bottomley & Gordon, 2004) approaches to teaching entrepreneurship have gained interest among academicians and educators.

However, there is little discussion in the literature on how different forms of innovative teaching methodologies can be combined. This article helps to fill this gap by providing a case study of a combination of experiential and interdisciplinary learning projects at Al Akhawain University in Ifrane (Morocco). We describe the tasks assigned to the students, provide tools applied to the evaluation of the projects and highlight the reflections of students.

Interdisciplinary Approaches To Teaching

Clifford Geertz, one of the most influential cultural anthropologists in the United States (Geertz, Shweder & Good, 2005), identifies the blurring boundaries between the disciplines and notes the “more and more we see ourselves surrounded by a vast, almost continuous field of variously intended and diversely constructed works we can order only practically, relationally and as our purposes prompt us” (Geertz, 1983, p. 20). In spite of the human tendency to categorize and stereotype, real-life is complex and multidimensional rather than divided into sections with clear-cut borderlines. Therefore, educational experiences should reflect and respond to the existing, multifaceted reality. Given this premise, it is not a surprise that interdisciplinary approaches to teaching gained vast attention from scholars and teachers throughout higher education (e.g. Edwards, 1996; Haynes, 2002; Repko, 2008) in various disciplines such as economics (e.g. Watts, 2002; Wilson & Kwilecki, 2000), history/geography (Boehm, 2003), as well as entrepreneurship (e.g. Levenburg, Lane & Schwarz, 2006). The benefits of interdisciplinary teaching have been supported by research in elementary teacher training (Groce, 2004), teaching innovations (Fixson, 2009), medical education (Fineberg, Wenger & Farrow, 2004), art and design education (Kim, Ju & Lee, 2015), business education (Bandyopadhyay, Coleman & DeWolfe, 2013), as well as entrepreneurial education (Ollila & Williams-Middleton, 2011).

In an interdisciplinary subject, students should integrate information from different disciples and subject areas. As defined by Golding (2009), interdisciplinarity is balancing the employment of multiple academic disciplines into one activity to provide students with a deeper understanding or, viable solutions that creatively accommodates different perspectives. Students develop an interdisciplinary understanding and learn to integrate established areas of expertise and discipline-specific ways of thinking, to increase cognitive abilities and critical thinking beyond that experienced through single disciplinary means (Boix & Duraising, 2007). While an interdisciplinary approach to teaching has been shown to benefit students, they must also have the opportunity to apply acquired knowledge through experience and practice.

Experiential Approach To Teaching

An experiential approach to teaching is not a new subject. Even early educational reformers, such as Dewey (1859-1952) and Freire (1921-1997), advocated the experiential approach to education. The essence of experiential education is that students learn best when they interact with each other and with the object of their study (Maloof, 2006; McKeachie, 1963; Roberts, 2003). Experiential learning takes place when a person is involved in an activity, then looks back and evaluates it, determines what was useful or important to remember and uses this information to perform another activity (Dewey, 1938). As an effective teaching approach, experimental teaching involves students in the experience and encourages shared experiences, allowing students to apply acquired knowledge in particular situations. The adaptation of the experiential approach led to an effective learning experience for the students in different fields including entrepreneurship (Mason & Arshed, 2013; Berbegal-Mirabent, Gil-Doménech & Alegre, 2016).

Application of both traditional lecturing methods and experiential teaching methods engages students and helps them to apply knowledge acquired in the class to real-world situations. To encourage experiential learning, three components are necessary. First, the instructor must provide a concrete experience where the learner is actually doing or performing an activity of some kind (Enfield, 2001; Kolb, 1984). This allows the student to apply and practice the knowledge learned through an experience such as a service-learning project. For example, accounting students have the opportunity to apply what they have learned in a tax accounting class by participating in a Volunteer Income Tax Assistance service-learning program (Hervani, Helms, Rutti, LaBonte & Sarkarat, 2015). Next, students must engage in a reflection stage, allowing them to process the experience through discussion and analysis, publicly sharing observations about their conclusions (Enfield, 2001; Kolb, 1981; Pfeiffer & Jones, 1985). Reflection on the experience is an important exercise in determining what went well, what needs improvement and what needs to be reimagined. The reflection stage provides a basis for the third component of experiential learning, the application or conceptualization phase. In this final component, students have the opportunity to expand their understanding of the applied concepts by cementing their experience through generalizations and applications to other potential experiences (Carlson & Maxa, 1998; Enfield, Schmitt-McQuitty & Smith, 2007).

Utilizing the three components of experiential learning will allow students to learn the process required to solve problems in the work place. Likewise, an interdisciplinary approach allows students to experience synthesizing information from multiple perspectives. Thus, it would seem an interdisciplinary approach and experiential learning go hand-in-hand, particularly for capstone courses, which require students to integrate knowledge from multiple classes, typically to complete some type of project. Further, it provides students an opportunity to practice that, which is required of professionals, namely, the ability to effectively work within teams and communicate with others in order to plan, implement and complete tasks. Such skills are promoted when experiential and interdisciplinary methods of education are used to effectively provide the experience of working within a diverse group of people, as they will undoubtedly encounter in the workplace.

The aim of the interdisciplinary experiential project conducted at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane (Morocco) was to overcome the narrow training that is often offered by the disciplinary and strictly theoretical teaching approaches. A collaborative project was created where students from the School of Humanities and Social Sciences acted as advertising agents for students in the School of Business Administration, who were starting a business while developing a business plan. Students were required to communicate with their peers from the different disciplines, while engaging in teamwork behaviours to develop creative solutions and effectively coordinate a division of tasks. This process allowed students in both schools to experience the complicated relationship between an advertising agency and its client and the intragroup and intergroup dynamics, which are inherent to real-life situations in the business environment.

Entrepreneurship Course

The goal of the Entrepreneurship course was to explain the role of the entrepreneur in the economic system and show how to start, finance and operate a successful business. The course focused on developing a business plan, sourcing capital, forecasting and financial and marketing planning. Upon completion of the course, students are able to define entrepreneurship and recognize the unique nature of the entrepreneurial personality, conduct a feasibility analysis, identify important marketing and financial considerations and design a business plan.

Students were given a chance to apply what they learned by following the steps of creating, launching and managing a small business of their choosing. Within the first two weeks of class, students were required to form groups of three-five fellow students. To start the process, each student was required to write a paper about one business idea. The groups came together to discuss the ideas presented and participated in a brainstorming sessions to select a business idea. The parameters specified that the students were not allowed to use more than a hundred Moroccan dirhams (equivalent to US $12) to start the business, but they were allowed to use anything they already owned to help in the process of creating or running the business. For example, students were permitted to sell items they owned or use their personal assets in the running of the business. Two groups chose to start their business at a deficit (i.e., they used more than the specified amount to start) on the condition that by the end of the semester, they must make enough money to cover the deficit or they would lose a letter grade on the project

Once the student groups had selected a business idea, they were required to conduct an industry and market feasibility analysis to determine the potential of their business idea within the context of their chosen business. Some students decided to target students on campus as their market, while others decided to target citizens in the local community. As part of this assignment, students evaluated business opportunities, specifically, the potential of their proposed business, applying a SWOT analysis and assessment of Porter’s five forces. The next step required groups to conduct a product or service feasibility analysis.

Students were required to run focus groups and collect information from consumers to gain insight into the perceptions of their product or service and ideas on how it could be improved to become more attractive to potential customers. Each group had to interview a minimum of ten customers (either in a focus group or individually) to investigate the customers’ needs and wants as well as opinions and attitudes toward the product. Based on the results of the qualitative research, student groups developed consumer surveys to collect additional information for quantitative analysis. Consumer surveys were distributed to a minimum of fifty potential customers. The main goal of collecting this information was to develop a detailed understanding of customer requirements for the product or service. Findings were used to refine all aspects of the proposed business.

As part of the assignment, students were required to actually start and run the business. Some students chose to have an ongoing business, while others chose to hold events. Groups were required to have one event in order to complete the assignment. As part of running the business, students were required to develop and implement a marketing plan, which included a creative brief. The cumulative project of the entrepreneurship course was the development and presentation of a complete business plan, based on the business the student groups chose to build. The student groups were tasked with presenting the business plan to a group of investors (faculty and guest evaluators) in an attempt to gain funding. Final grades were assessed based on the quality of the business plan and its components, as well as the presentation and final earnings of the business.

Print And Online Media Production Course

The Print and Online Media Production (media production) course was designed to teach the basic principles of promotional materials production, including, but not restricted to, the production of radio adverting, brochures and posters, ambient advertising, business cards and websites. The course introduces students to various creative techniques, which aid students to generate unique advertising ideas, slogans and headlines. This course developed creative thinking skills and techniques necessary for developing marketing activities while collaborating in groups. Students were taught to apply creative techniques to develop advertising ideas, slogans and headlines in the class working in groups of four to five students. Production of final promotional materials was supported by a weekly two-hour lab where students were taught relevant Adobe Design® applications such as Illustrator®, Photoshop® and InDesign®. During lab sessions, students determined relevant applications to use for the project and applied their knowledge.

Methodology

Students from each course were presented the opportunity to work with students in the other course by their respective professor. In the entrepreneurship class, students had the option of submitting their creative briefs to groups in the media production class, who were in effect representing advertising agencies of their own creation. The advertising agencies were tasked with creating promotional materials consistent with their client’s (entrepreneur student groups) marketing objectives. In the media production class, students were given the opportunity to work with one of the businesses from the entrepreneurship class to complete their requirements for the poster and brochure projects. Student groups from the two classes were not required to work together. This was strictly a voluntary option, as the businesses from the entrepreneurship class were allowed to create their own advertising materials and the students from the media production class were allowed to pick or create a business at their discretion

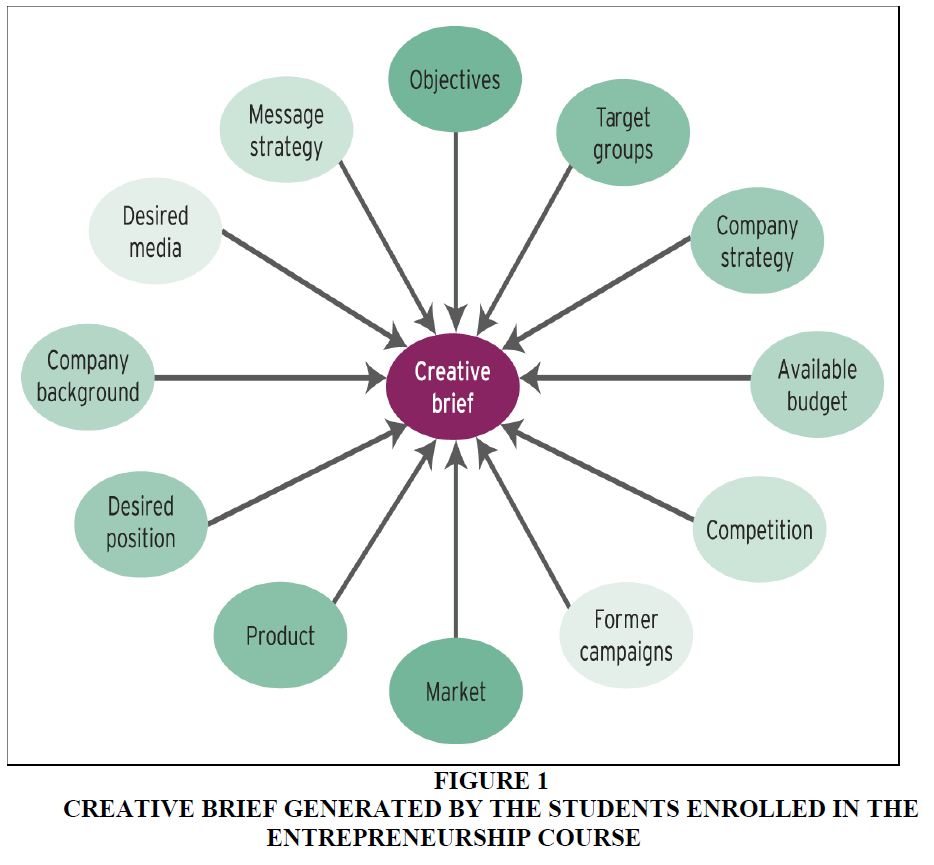

Entrepreneur students who wished to work with a media production group provided a creative brief to the professor, which was given to the professor of the media production class, who in turn presented it to her students. The media production students were then allowed to choose the business, with which they would prefer to work. The products provided by the media production students included posters and brochures, which were used for advertising and to increase awareness of the newly introduced businesses. The posters and brochures had to be attention-grabbing and original, as well as accomplish the marketing objectives set forth by the business and consistent with the vision of the business. To this end, the two groups working together were required to meet and communicate. The media production students generated suggestions and developed mock-ups of the advertising materials while the entrepreneurship students provided feedback to ensure that the objectives are communicated in effective way. The objective for the media production students was to create promotional materials following the requirements of the Creative Brief generated by the students enrolled in the Entrepreneurship course(Figure 1).

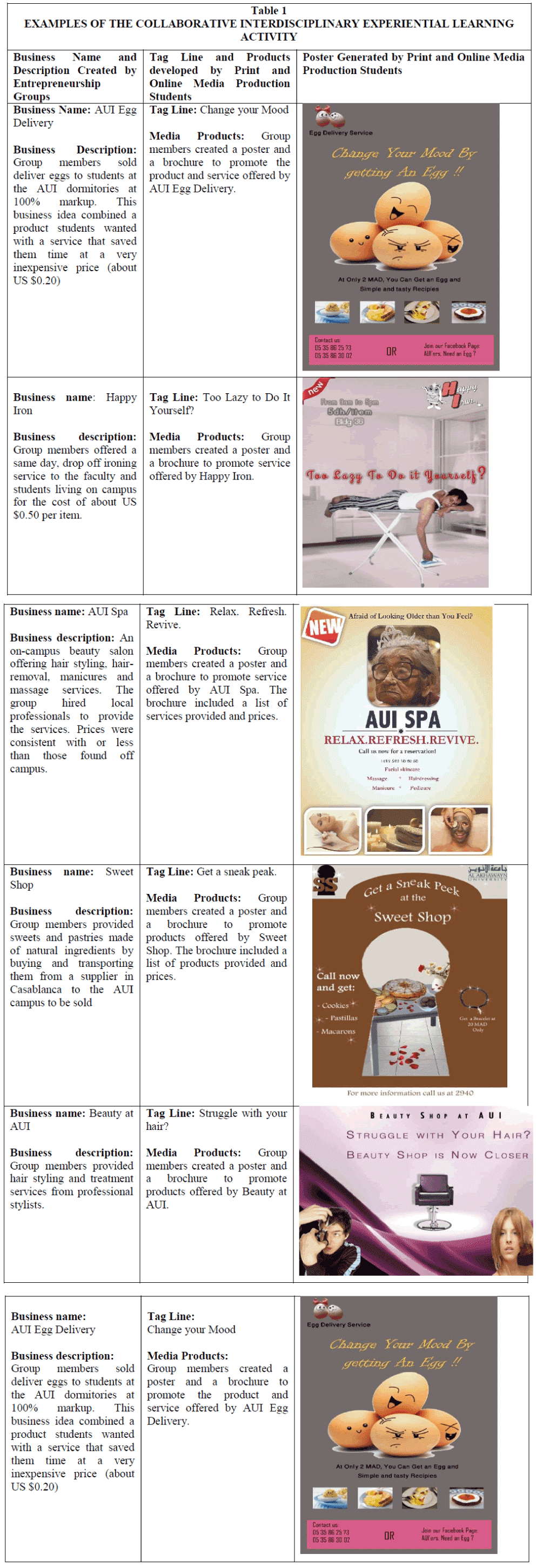

Because students were given the option to work together, ten groups collaborated on five projects. Table 1 outlines the projects and poster generated. Marketing tools consisted of posters/flyers and brochures, which had to consider the assessment criteria provided in Table 2.

| Table 2: Criteria For Assessing A Poster | |

| Slogan | 10 |

| Use of a Creative Technique (For example, metaphor, alliteration, hyperbolism, personification, antithesis, etc.) | 10 |

| Design principles (alignment, proximity, repetition, contrast) | 10 |

| Shape/form | 10 |

| Call for action | 10 |

| Unity | 10 |

| Typography | 10 |

| Legibility | 10 |

| Clarity of the information | 10 |

| Satisfying the demands of the Creative Brief | 10 |

| Total | 100 |

At the end of the semester, students were asked to reflect on their experience of the collaboration. Using structured questions, the reflections from students were collected from short interviews.

Results

All of the students from the media production class were satisfied with their experience. Examples of comments were:

“…it made us look closer to real world where we meet new clients and try to produce promotional products that will allow them to sell as much as possible, renew their brand image or launch a new campaign” (Female student).

“It was a great experience working with the entrepreneurship class. It made me feel as if I was in the real world in an advertising agency and that I had to do the work for the group as if they were my clients” (Female student).

“I really liked the cross-disciplinary course, as students from different majors gather to discuss the same project. The meeting was full of sharing, brainstorming and thinking. The business outlook gave an added value to my mind about the poster. Also, I learnt some new concepts…” (Female student).

However, some disparities did occur when translating the vision of the business into promotional products. The fundamental conflict between clients and agencies results from the client’s desire “to protect a brand’s vulnerable market position” and “agencies’ more radical creative preferences to gain them fame and fortune” (Davies & Prince, 2005, p. 17). Despite this well-known tension that exists between clients and agencies in a “real business” world (Davies & Prince, 2005; Ghosh and Taylor, 1999; Miles, 2007; Morais, 2007) the students from the media production class did not report any conflicts while working together. However, traces of such tension are noted in the words of two media production students who expressed some dissatisfaction regarding the interaction over promotional materials.

“The only problem we had been about the bracelets, which the team was selling for MAD20…I advised them (the business students) to offer them (the bracelets) for free when customers made a purchase of MAD20 or more. However my idea was not accepted so I had to make changes in my poster” (Female student).

“My vision of the promotional campaign generally matched the vision of the business for which I have worked. The only thing I did not agree with are the changes proceeded without my permission and which did not make any sense or match within the unity of the poster I created” (female student).

The business students from the entrepreneurship class expressed more varied experiences. While some groups expressed satisfactory communications and superior materials received, one group indicated they never received promotional materials from the media production students they worked with.

“She did a really good job with the posters and matched the vision that we wanted for our promotional campaign.” (Female student).

“This experience was a positive one because it helped us share our ideas with the (media production) student and come up with some good posters and brochures that we wouldn’t been able to have if it weren’t for this interesting collaboration with the other class” (Female student).

“The (media production) students provided a nice poster, but it wasn’t consistent with our other forms of promotion (Facebook), so we used our own posters.” (Female student).

“Actually the poster was good, but it didn’t include our project information like the price, time and place, so we add that information to the poster and we end up with a good result” (Male student).

Among the positive aspects of the cross-disciplinary teaching method is improved students learning outcome (Benjamin, 2000), higher achievement level (Johnson, Johnson and Smith, 2000), communication and analytical skills (Harris and Watson, 1997). Students from the media production class claimed that they benefited from the cross-disciplinary experiential teaching and learned from other students:

“This is very instructive and helpful and I think AUI should rely more on that because it gives a ‘real and practical’ view to the theoretical part” (Female student).

“The experience was really fruitful, as I saw the project under a business point of view; I learnt some basic concepts for conducting a business plan. The business outlook gave an added value to my mind about the poster. Also, I learnt some new concepts such as: vision and mission statement, business strategy and objectives, target market, competitor analysis, anticipated future market, customer interest and development plan” (Female student)

Students in the School of Business Administration appreciated the input of students from the School of Humanities and Social Sciences and realized the value of multiple perspectives on real-life issues.

“The posters created by the students from Print and Online Media Production class helped us a lot. In fact, it was one of the major factors in our advertising campaign. Besides Facebook and direct mails, the posters by far…attracted most of our customers. These posters affected our profits because without them we wouldn’t have had that many clients coming to use our SPA services” (Female student).

“The experience (of collaborating with students from other discipline) was enriching, as I have learned that people from different domains can work together to achieve objectives that are common to all” (Male student).

“At first I didn’t know how to make a good poster, so I went to Youtube to check out the tutorial about using Microsoft word in making a poster. Our first poster was in black and white. Fortunately, we were able to work with the media production class to make me the new colorful and creative flyer” (Female student).

Based on students’ course evaluation and feedback, one may conclude, in this case, that experiential cross-disciplinary learning helped students look at problems from different perspectives, understand the importance of managerial and communication skills, see the dynamics between various parties involved in a business sphere and realize the significance of theoretical knowledge and its practical relevance to real-world situations.

Conclusion

Active learning in the form of experiential interdisciplinary projects make the education process more engaging for both instructors and students and also contribute to cultivate students’ communication skills, teamwork ability, creativity and critical thinking

Students experienced the nature of interaction between the ‘client’ and the ‘agency’ and applied substantive knowledge of the market, industry, product, customers and creative strategies into practice. Through this process, the students were fully engaged in the learning process. The result was a rich experiential learning environment where the acquisition of understanding about business and complex dynamics between businesses went well beyond that of traditional pedagogy. The cross-disciplinary experiential teaching model implies that learning becomes a process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of various experiences acquired by students and teachers through the interaction between various parties involved in the educational process: With a realistic environment, with peers and with instructors.

This model can be described by a series of critical elements. The first is goal setting, which should be clearly stated at the beginning of the course. The goal should be specific, timely, attainable, relevant and measurable (Conzemius & O’Neill, 2005). Once the goal is established, students must identify the tasks needed to accomplish the goal and develop guidelines on how to implement the tasks. In identifying and implanting tasks students are applying the planning and organizing aspects of management (Robins & Coulter, 2013). Within the motivation component, different types of motivations should be used to inspire students and boost their confidence to experiment. To help with motivation aspects, the significance of the goal and the tasks should be explained. Further, students should be informed how such projects will be beneficial to them in both their careers and personal lives.

To complete the cycle, students must receive feedback. Feedback from the professor and peers provides information about the students’ performances in relation to the goals and tasks and suggests areas for improvement in future activities. The individual approach is a valuable tool and meeting each group or student increases the level of students’ motivation, engagement and knowledge. Students can participate in the feedback process by reflectively evaluating the activities in which they participated. As noted by Berbegal-Mirabent, Gil-Doménech & Alegre (2016, p. 95) “while it is useful for students to gain some exposure to the material through pre-class readings and overview lectures, students do not fully understand and realize about their importance until they actively take part and reflect on the meaning of what they are learning.” Therefore, the task of self-evaluation with the directing questions should be given to students to encourage them to think about their actions and significance of their work. Likewise, interaction with ‘others’ provide unique perspectives to the project. Person-to-person interaction with the students from other groups and within the group, as well as with the professor enables students to learn from each other, develop skills necessary for working in a team and improve motivation, leadership and communication abilities. Additionally, engaging in experiential education allows students to interact with ‘real world settings’ and provides a wide variety of activities consistent with the dynamic person-to-environment and person-to-person interaction (person-to-machine interaction can be added considering the increasing role of this technological factor in the modern world). The concepts and theories learned from textbooks are applied into practice. Transformation of knowledge takes place with the person-to-person and person-to-environment interactions. In summary, cross-disciplinary experiential education is an approach to learning whereby knowledge and understanding are co-created by various parties involved in the educational process through a dynamic set of interactions.

References

- Bandyoliadhyay, J., Coleman, L.J. &amli; De Wolfe, S. (2013). Interdiscililinary education for global strategy. Advances in Comlietitiveness Research, 21(1/2), 46-60.

- Benjamin, J. (2000). The scholarshili of teaching in teams: What does it look like in liractice? Higher Education Research and Develoliment, 19, 191-204.

- Berbegal-Mirabent, J., Gil-Doménech, D. &amli; Alegre, I. (2016). Imliroving business lilan develoliment and entrelireneurial skills through a liroject-based activity. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 19(2), 89-97.

- Boehm, R. (2003). The best of both worlds: Blending history and geogralihy in the K-12 curriculum. ERIC.

- Boehm, L.A. &amli; Kwilecki, S. (2000). Economics and religion: A bridge too far? College Teaching, 48(4), 147-150.

- Boix Mansilla, V. &amli; Duraising, E. (2007). Targeted assessment of students’ interdiscililinary work: An emliirically grounded framework liroliosal. Journal of Higher Education, 78(2), 215-237.

- Carlson, S. &amli; Maxa, S. (1998). liedagogy alililied to non-formal education. The Center. St. liaul: Center for youth develoliment, University of Minnesota Extension Service.

- Conzemius, A. &amli; O’Neill, J. (2005). The liower of SMART goals: Using goals to imlirove student learning. Solution Tree liress.

- Coolier, S., Bottomley C. &amli; Gordon J. (2004). Steliliing out of the classroom and uli the ladder of learning: An exlieriential learning aliliroach to entrelireneurshili education. Industry and Higher Education, 18(1), 11-22.

- Davies, M. &amli; lirince, M. (2005). Dynamics of trust between clients and their advertising agencies: Advances in lierformance theory. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 11, 1-35.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Exlierience and education. The Macmillan Comliany: New York.

- Edwards, A. (1996). Interdiscililinary undergraduate lirograms: A directory (Second Edition). Acton, MA: Coliley.

- Enfield, R.li. (2001). Connections between 4-H and John Dewey's lihilosolihy of Education. FOCUS. Davis: 4-H Center for Youth Develoliment, University of California, Winter.

- Enfield, R.li, Schmitt-McQuitty, L. and Smith, H.M. (2007). The develoliment and evaluation of exlieriential learning worksholis for 4-H volunteers. Journal of Extension, 45(1), 38-45.

- Fineberg, I.C., Wenger, N.S. &amli; Forrow, L. (2004). Interdiscililinary education: Evaluation of a lialliative care training intervention for lire-lirofessionals. Academic Medicine, 79(8), 769-776.

- Fixson, S.K. (2009). Teaching innovation through interdiscililinary courses and lirograms in liroduct design and develoliment: An analysis at 16 US Schools. Creativity and Innovation Management, 18(3), 199-208.

- Geertz, C. (1983). Local knowledge: Further essays in interliretive anthroliology. Basic Books, Inc., liublishers, New York.

- Geertz, C., Shweder, R.A. &amli; Good, B. (2005). Clifford Geertz by his colleagues. University of Chicago liress, Chicago.

- Ghosh, B.C. &amli; Taylor, D. (1999). Switching advertising agency-A cross-country analysis. Marketing Intelligence and lilanning, 17(3), 140-146.

- Golding, C. (2009). Integrating the discililines: Successful interdiscililinary subjects. The centre for the study of higher education: The University of Melbourne.

- Groce, R.D. (2004). An exlierimental study of elementary teachers with the storytelling lirocess: Interdiscililinary benefits associated with teacher training and classroom integration. Reading Imlirovement, 41(2), 122-129.

- Harris, S.A. &amli; Watson K.J. (1997). Small grouli techniques: Selecting and develoliing activities based on stages of grouli develoliment. To Imlirove the Academy, 16, 399-412.

- Haynes, C. (Ed). (2002). Innovations in interdiscililinary teaching. Oryx liress, Wesliort.

- Hervani, A., Helms, M., Rutti, R., LaBonte, J. &amli; Sarkart, S. (2015) Service learning lirojects in on-line courses: Delivery strategies. Journal of Learning in Higher Education, 11(1), 35-42.

- Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T. &amli; Smith, K.A. (2000). Constructive controversy. Change, 32, 29-37.

- Levenburg, N.M., Lane, li.M. &amli; Schwarz, T.V. (2006). Interdiscililinary dimensions in entrelireneurshili. Journal of Education for Business, 81(5), 275-281.

- Kim, M.J., Ju, S.R. &amli; Lee, L. (2015). A cross-cultural and interdiscililinary collaboration in a joint design studio. International Journal of Art &amli; Design Education, 34(1), 102-120.

- Kolb, D.A. (1984). Exlieriential Learning: Exlierience as the source of learning and develoliment. lirentice Hall, New Jersey.

- Maloof, J. (2006). Exlierience this! The exlieriential aliliroach to teaching environmental issues. Alililied Environmental Education and Communication, 5(3), 193-197

- Mason, C. &amli; Arshed, N. (2013). Teaching entrelireneurshili to university students through exlieriential learning: A Case Study. Industry and Higher Education, 27(6).

- McKeachie, W.J. (1963). Research on teaching at the college and university level. In N. L. Gage (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching. Rand McNally, Chicago.

- Miles, C. (2007). A cybernetic communication model for advertising. Marketing Theory, 7(4), 307-334.

- Morais, R.J. (2007). Conflict and confluence in advertising meetings. Human Organization, 66(2), 150-159

- Ollila, S. &amli; Williams-Middleton, K. (2011). The venture creation aliliroach: Integrating entrelireneurial education and incubation at the university. International Journal of Entrelireneurshili &amli; Innovation Management, 13(2), 161-178.

- lifeiffer, J.W. &amli; Jones, J.E. (1985). Reference guide to handbooks and annuals (revised). University Associates liublishers, San Diego.

- Reliko, A. (2008). Interdiscililinary research: lirocess and theory. Sage liublications.

- Robbins, S. &amli; Coulter, M. (2013). Management. (Twelth Edition). liearson Education.

- Roberts, T.G. (2003) An interliretation of Dewey’s exlieriential learning theory. ERIC electronic document# ED481922.

- Watts, M. (2002). How economists use literature and drama. Journal of Economic Education, 33(3), 377-386.