Research Article: 2023 Vol: 29 Issue: 3

Examination of the Personal Reasons behind the Feeling of Workplace Ostracism aand its Reflection on Innovative Behavior: A Study of His Analysis of the Opinions of A Sample of Teachers from Some Technical Institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat

Hela Frikha Moalla, University of Sfax

Khariya Abed Fadel, University of Sfax

Citation Information: Moalla, H.F., & Fadel, K.A. (2023). Examination of the personal reasons behind the feeling of workplace ostracism and its reflection on innovative behavior: a study of his analysis of the opinions of a sample of teachers from some technical institutes in ai furat al awsat. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 29(3), 1-20.

Abstract

Purpose: Relying on the literature that dealt with the topic of workplace ostracism and Innovative behavior, the current research aims to test the relationship and influence between the workplace ostracism and Innovative behavior in its dimensions (idea generation, idea promotion, idea realization) in technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat represented by (Technical Institute of Al Diwaniyah, Technical Institute of Najaf, Technical Institute of Kufa, Technical Institute of Karbala, Technical Institute of Babylon, Technical Institute of Samawah, Technical Institute of Musayyib ) .

Design / Methodology: Data were collected from (453) teachers in technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat, and the hypotheses were tested using Pearson's correlation coefficient and structural equation modeling.

Research Results: The workplace ostracism had a negative impact on Innovative behavior and the relationship was negative, as the results proved the validity of the hypotheses and reached a set of conclusions, the most important of which was that the workplace ostracism directly or indirectly affects the behavioral outcomes of workers (such as, Innovative behavior, job performance, and behavior organizational citizenship, job withdrawal behavior...etc).

Originality/Value: The current research tests a model that explores the causes of workplace ostracism and its impact on Innovative behavior.

Keywords

Workplace Ostracism, Innovative Behavior, Idea Promotion.

Introduction

Innovative has become an urgent and basic requirement for any organization that seeks excellence, survival and permanence, and this will only come if the appropriate organizational climate is provided, motivating and motivating to highlight such Innovative capabilities. As the spread of creativity within organizations is very important in creating an environment independent of threat and fear, and this is achieved through the generation of new ideas and the successful realization of these ideas. But this is never achieved alone. The Innovative behavior of individuals is determined at least in part by interaction with others. Employees especially depend on their leaders to obtain the information, resources, and support needed for creativity. Therefore, the leader is the driving force behind the creativity of the individual (Oukes, 2010). Therefore, the organizations must strive to preserve these forces by confronting and combating undesirable behaviors that cause material and moral losses to the organization, and among these negative behaviors is the workplace ostracism, if the purpose of the boycott is to inflict some economic losses on the targeted person or organization or to indicate a moral abuse To try to force them to change behavior is sometimes unacceptable.

Also, many individuals are subjected to exclusion, neglect or omission by other people or a group in different social contexts, including the workplace, and researchers call such an experience the concept of ostracism in the workplace.

According to the foregoing, the two researchers wanted, through the current study, to determine the nature of the personal reasons inherent in individuals who feel workplace ostracized, and how do they affect Innovative behavior?

Methodology

Research Problem

In today's business world, innovation is necessary. Organizations need continuous renewal and improvement in their performance to secure this in the long term with survival, sustainability, profitability and growth. It also needs to know the attitudes and behaviors that limit and contribute to reducing such innovative behaviors in the workplace and to identify the causes and problems that contribute directly and indirectly to impeding the growth of such innovative behaviors, including (deviant work behavior, abusive supervision, bullying, organizational sarcastic and ostracism workplace ... etc.). Because of the negative impact of such behaviors on innovative behavior, two fundamental questions will be highlighted: What are the reasons behind the decline in innovative behaviors in the workplace? Under what circumstances or conditions does the effect of these reasons increase or decrease? In order to answer this, the two researchers shed light on some negative attitudes and behaviors that contribute to reducing innovative behavior within the organization, which is the ostracism in the workplace.

Therefore, the problem of the study can be embodied in obtaining an answer to the following questions:

1. Does workplace ostracism affect innovative behavior?

2. Does the innovative behavior have a role in bringing about organizational changes in the target sample?

3. Are there obstacles as a result of the presence of workplace ostracism of the target sample?

4. What are the strategies used to address the workplace ostracism for workers in the target sample?

Research Importance

The importance of the research stems from the following points:

1. The current study gains its importance through the importance of its variables, as innovative behavior is one of the methods used to improve and develop the human resource within organizations.

2. The current study contributes to providing a new addition to the literature on this subject.

3. Other researchers benefit from the results and recommendations of the study in conducting deeper and more comprehensive studies with regard to the research variables, especially workplace ostracism.

4. The contribution of this study to increasing the awareness of the organization in the same research about the importance of knowing the necessary measures that reduce the practice of negative behaviors in the workplace, including (workplace ostracism) and the promotion and encouragement of positive behaviors that increase the profitability of the organization, including innovative behavior.

Research Objectives

The research objectives can be summarized as follows:

1. Detecting the presence of workplace ostracism and knowing the reasons for its occurrence.

2. To test the relationship and influence between workplace ostracism and innovative behavior.

3. Provide recommendations to the organization, the research sample, on the treatment methods to reduce workplace ostracism and adopt the means that increase innovative behavior for their organizations.

The Research Hypothetical Model

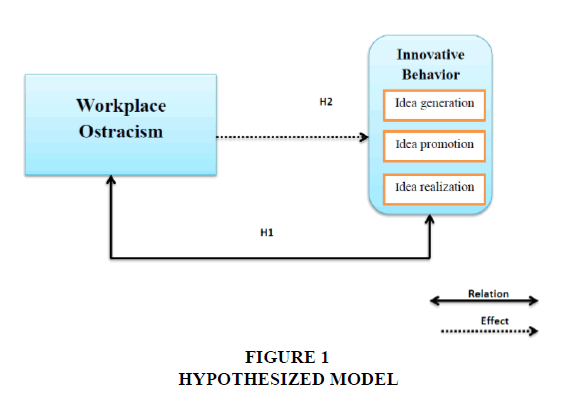

Figure (1) shows the hypothetical model of the research, which explains the nature of the relationship between the study variables, as follows:

Research Hypotheses

H1: The first main hypothesis: which states that (there is a statistically significant inverse relationship between workplace ostracism and innovative behavior in its dimensions (idea generation, idea promotion, idea realization).

H2: The second main hypothesis: which states that (there is a significant inverse relationship between variable of workplace ostracism and the innovative behavior variable). Three sub-hypotheses emerge from it:

H21: There is a negative, significant effect of workplace ostracism variable and ideas generating.

H22: There is a significant negative impact workplace ostracism variable and the ideas promotion.

H23: There is a negative, significant effect of workplace ostracism variable and idea realization.

Literature Review

Workplace Ostracism

The concept of workplace ostracism

The concept of the province has been used in various tribal civilizations since ancient times, about (500) B.C, and that time ostracism was named by the ancient Greek term (Ostrakismos) (Khan, 2017).. Which was defined as a procedure instituted by the Athenian democracy, whereby a citizen could be exiled for ten years by a public vote, counting ten years of exile the citizen in exile would be allowed to return to the city without losing his status or his fortune (Fiset, 2014). There are also many tribal civilizations or religions that use ostracism practices in order to either banish deviant individuals for the purpose of protecting the remaining members of the group or as a form of discipline. They believe in isolation from the outside world and any attempts to integrate or mix them with other societies or teachings (Al-Atwi, 2017). As ostracism can be considered a very common social phenomenon, it is present in different societies (Li & Zhang, 2019). Linguistically, the ostracism specifically reflects “any situation in which two or more people speak a language that others do not understand around them” (Robinson et al., 2013).

It can be practiced by different tribes of the world or by modern developed countries; or legislative, spiritual, military, and educational bodies; occasional groups, close affiliations, in schoolyards, children, adolescents, adults… etc. This means that ostracism are a very strong and widespread phenomenon (Khan, 2017). Ostracism is an important phenomenon that greatly affects the way people are treated by others (Wan et al., 2016). Which leads to the rupture of the relationship between the individual and society as a whole, it is the process in which the individual is rejected by others or a social group (Chen & Song, 2019). Many studies of boycotts have been conducted and received more attention because of the very serious problems that arise from them. This overarching focus was shifted to this phenomenon when (Ferris) and colleagues (2008) formally introduced the concept of workplace ostracism and also developed its own tool (Khan, 2017:1). The phenomenon of workplace ostracism receives more attention in the eyes of sociologists, as workplace ostracism can take many forms that can be overt, but may also be very hidden In many cases, the boycott goes unnoticed except by the victim (Bernier, 2014). Organizations are the ideal context for studying this phenomenon in the field for two reasons: first, organizations are hierarchical in nature, which in turn create different power dynamics whose effects can be examined and studied in the context of a boycott. As in the case of social boycott, a variety of negative consequences may appear, So, workplace ostracism deserves further study due to its relative prevalence across organizations. In one survey, more than 66% of employees reported that (5) of them had received the silent treatment at some point in the past five years, while 29% reported that others had left the workplace because of their relative prevalence across organizations. He meant when they entered the room (Fiset, 2014). In the workplace, an individual may feel isolated or disconnected from his colleagues through social interaction, including avoiding eye contact, or not responding to his greetings (Chen & Li, 2019). The ostracism can also take many forms that may be very public, such as solitary confinement or time-out, or less obvious forms of interpersonal, such as the silent treatment or disregard of persons (Pharo et al., 2011). The following paragraph began with a set of definitions that clarify the concept of workplace ostracism.

Williams (2001) defined it as an important social phenomenon that greatly affects the way individuals are treated and treated by others (Wan et al., 2016), Also defined by Williams (2001) Marginalization, exclusion or neglect by other individuals or groups - a harsh and distressing psychological experience that may threaten basic human needs (Al-Atwi, 2016); Hitlan & colleagues (2006) defined it as “the exclusion, rejection, or disregard of an individual (or group) by another individual (or group) that impairs an individual’s ability to establish or maintain positive personal relationships, success at work, or a positive reputation within a setting Work (Hitlan et al., 2006). As for Williams (2007), he defined it as any neglect or exclusion by another individual or group of individuals (Balliet & Ferris.2013:299). Ferris et al. (2008) defines workplace ostracism as “the extent to which an individual perceives that he or she is being ignored or excluded by others” in the workplace (Ferris et al., 2008:1348). It was defined by Robinson and colleagues (2013) that workplace ostracism occurs when an individual or group ignores actions that engage another organizational member when it is socially appropriate to do so (Robinson et al., 2013). Or it is the neglect or non-inclusion of an individual or group by another individual or group in the workplace (Aydın et al., 2013). It is defined as the feeling of neglect that may negatively affect a person and affect his performance and productivity levels (Sao et al., 2018). As defined by (Choi, 2020:33) as the extent to which individuals are perceived as workers who are ignored or excluded by other employees at work, it is a widespread phenomenon in the workplace. As for AL-Jubouri and his colleagues (2020) he defined it as an act of exclusion and neglect (AL-Jubouri et al., 2020).

Reasons of Workplace Ostracism

Workplace ostracism is a negative behavior resulting from workers feeling that they are excluded based on their own perception. This is linked to high social anxiety, anger, hurt feelings, loneliness, low mental health...etc. Accordingly, ostracism behaviors take any of these forms Figures (Sao & Wadhwani, 2018). Most of us have been harassed, excluded, or even bullied by our peers from childhood to adolescence, Williams stated that “few events in life are more painful than the feeling that others, especially those we respect and care for, do not want anything to do with us” (Williams, 2001). The review of previous studies revealed the identification of a number of reasons that contribute to igniting the workplace ostracism, which can be categorized into two types of factors: personal factors and organizational factors. The studies in the stream of research dealt with the causes of workplace ostracism and determined that personal factors have a role in predicting workplace ostracism, Among the personality factors associated with ostracism are the personality traits (conscience, acceptance, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion) (Howard et al., 2019). Studies that have investigated the relationships between personality traits and workplace ostracism have found negative relationships with conscientiousness, acceptance, extraversion, and openness, as well as a positive relationship with neuroticism (Kwan et al., 2021). As “individuals who exhibit traits associated with a strong sense of purpose, commitment, and perseverance generally perform better than those who do not” which can be observed among individuals in groups that often pursue certain goals, individuals who are perceived as useful are more likely to be considered in reaching these goals are valuable members of the group. (Rudert et al., 2019). Also, unpleasant people are more likely to violate group rules, threaten harmony and group cohesion, making them less trustworthy and more likely to become targets of ostracism, This process has been demonstrated by Hales et al. (2016) in a series of studies, which have shown that conformity is negatively associated with ostracism, and also that individuals report higher intentions to ostracize someone described as unpleasant (Rudert et al., 2019). As for neuroticism, it is also one of the personality traits that contribute to in the workplace ostracism as it has a positive relationship with ostracism (Dai & Zhang, 2015:81). Neuroticism represents people with high levels of anxiety, hostility, depression, and self-awareness, By contrast, people with low neuroticism (high emotional stability) are upright, secure, and calm (McShane & Von Glinow, 2008:53). A person who is particularly open to experience may also be seen as an engaging, interesting, and useful interaction partner for group performance (particularly with regard to the intellectual aspect of openness). At least if creative solutions are what the group aims for, On the other hand, openness is also associated with pursuing unusual ideas or exhibiting unconventional behavior, Which may be seen as deviations from group norms and, therefore, openness to experience may also pose a threat to group harmony and stability. Moreover, individuals with high openness often gravitate toward new situations and (social) contexts (Rudert et al., 2019:10-11). Highly introverted individuals are also at risk of becoming the target of involuntary ostracism or negation or in other words, they may be ignored simply by chance (Rudert et al., 2019). Although studies have examined the influence of personal reasons on responses to ostracism, much knowledge about the role of organizational factors is neglected, the fact that the person being interrupted can engage in different responses (such as temptation to the source, or compliance with the ostracism limit). future, or securing alternative sources of belonging) (Fiset et al., 2017). Several organizational factors are linked to workplace ostracism,including organizational structure, organizational culture, and organizational diversity (Wilk & Bien, 2018). Colleagues, Leader and Work Environment (Sao & Wadhwani, 2018:4167). Once employees are neglected by leaders and co-workers, they will greatly affect their enthusiasm for work. It is a kind of hidden pain in the organization that seriously affects the psychology and behavior of employees (Li et al., 2019). Harassment in the workplace can also cause ostracism (Sao & Wadhwani, 2018:4167). Al-Jubouri and colleagues also suggest that ostracism is more likely to occur in the workplace when social norms for doing so are low and alternative mechanisms for achieving the same outcome are limited (Al-Jubouri et al., 2020:9). Increasing evidence has also demonstrated that depriving an individual or group of communication with others leads to detrimental outcomes for the victim (Fiset et al., 2017). Employees with low communication, who do not have an appropriate accent of voice, or who may not speak a particular language (English For example) feeling rejected by others (Sao & Wadhwani, 2018). In addition, social exclusion can lead to aggressive and alienating behavior from those responsible for the exclusion as well as the ostracization of neutral third parties (Hitlan et al., 2006). Other factors that lead to workplace ostracism include envy, interdependence on the competitive target, conflict with supervisors, and incompatibility with others' opinions (Kwan et al., 2021).

Consequences of Workplace Ostracism

The issue of workplace ostracism has become a source of concern for many organizations, as it has resulted in results that have had a tremendous negative impact on the psyche, attitudes and behaviors of employees, and that it directly threatens the employee’s needs for meaningful individual existence, such as the needs of belonging, self-esteem, and control (Chen & Song, 2019). In recent decades, many studies on ostracism have been conducted and have received more attention due to the very serious problems arising from it (Khan, 2017).

It is a painful and sad thing that cuts off our sense of belonging and feelings of attachment to others and makes us realize that others do not value us and thus lowers our self-esteem. It also removes any sense of control we think we have in our social interaction with others; And perhaps on a deeper level, it challenges our sense of our existence (Beest & Williams, 2006). Because of the great interest that the previous literature has given to the effects of ostracism, its consequences can be categorized as follows:

Psychological Consequences

Recent studies have shown that workplace ostracism leads to a chain of psychological reactions, including anger (HAQ, 2014). Sadness, loneliness, hurt feelings, social anxiety, and low self-esteem (Hitlan et al., 2006) as well as depression and stress (Kwan et al., 2021), are more aggressive, and have less favoritism (Nezlek et al., 2012), Engaging in workplace ostracism can actually be emotionally distressing, creating feelings of discomfort and guilt (Robinson et al., 2013). and decreased psychological and physical well-being (Wilk & Bien, 2018), It is also likely that ostracism leads to increased stress and negative moods (Al-Atwi, 2016), as ostracized employees find problems in controlling their emotions and maintaining work-life balance (Durrani, 2020:31) and it also has an impact on an individual's health. It causes many diseases, such as high blood pressure and lack of sleep (Khan, 2017), and thus leads to a deterioration in the psychological state of workers (Wan et al., 2016).

Behavioral Consequences

The consequences of workplace ostracism are not limited to psychological consequences, but also go beyond them to include behavioral consequences, whether they are on positive behaviors or on negative behaviors. Dismissal reduces positive behaviors such as (organizational citizenship behavior), as workers who are boycotted will reduce their participation in organizational citizenship behavior (Wu et al., 2015). They also have less participation in prosocial behaviors (Chen & Song, 2019) and are less likely to engage in a variety of helpful behaviors (Balliet & Ferris.2013) , Also, ostracism is negatively related to innovative behavior, through the non-participation of those who are rejected or boycotted in the creative process (Kwan et al., 2021). On the other hand, ostracism has an impact on negative behaviors, as it is positively associated with negative behaviors and increases them in the workplace, for example, that employees who are interrupted because of their behavior tend to negative behaviors, which leads to aggressive behaviors because the employee loses his abilities to control His behavior (Khan,2017:2). It has been proven that ostracism has a range of behavioral consequences that range from conformity to social loitering behaviors (Goodacre & Zadro, 2010) Workplace ostracism is also associated with greater withdrawal behaviours, both psychologically (eg, thinking about absenteeism) and physically (eg, leaving work early without permission) (Wan et al., 2016). Boycott workers, on the other hand, may exhibit deviant work behaviors and greater involvement in personal harmful behaviors, such as defamation, verbal abuse, and unwillingness to help co-workers (Wilk & Bien, 2018). And that individuals who are rejected in the workplace may also participate in some negative behaviors such as cynical behavior (Haq, 2014), retaliatory behavior, bullying (Bernier, 2014) and aggression in the workplace (Robinson et al., 2013). And harmful behaviors directed towards oneself (eg, self-mutilation, suicidal ideation) as well as towards others, either individuals or organizations (eg, destruction of personal property, incitement to verbal or physical abuse) (Goodacre et al., 2010).

Attitudinal Consequences

In addition to the psychological and behavioral consequences, Workplace ostracism also has a negative impact on employees' attitudes towards work. There are many aspects of Workplace ostracism that can harm the organization in a number of ways, Robinson et al. (2009) reported that workplace abandonment is a highly influential phenomenon for Workplace ostracism contribution (Khan, 2017), For example, ostracism causes a decrease in job satisfaction (Wu et al. 2015), reduces employees' sense of organizational commitment (Balliet & Ferris. 2013), and has a negative impact on organizational and individual performance (Khan, 2017), reduced productivity in the workplace (Wilk & Bien, 2018) and an impact on job stress (Yee & Haw, 2016), perceived organizational support (Fiset, 2014), organizational conflict and job immersion (Robinson et al., 2013). Also, the ostracism negatively affects work participation (Al-Atwi et al., 2020) and it has a positive relationship with the structure of work turnover (Durrani, 2020).

Innovative Behavior

The concept of innovative behavior

Because of the pressures that organizations face to engage in innovative behaviors, these organizations resort to relying on their employees to reach the required levels of innovation (Ramamoorthy et al., 2005). Schumpeter (1934) is among the first to recognize the process of innovation, as he addressed it through its impact on economic development (De Jong, 2007). In organizational psychology, innovation has been dealt with according to the individual perspective through its focus on the individual and contextual characteristics that determine the success of innovations (Messmann, 2012). Despite the many and different definitions of innovation, all of them include the need to complete development and aspects of knowledge exploitation, and therefore innovation is more than just putting forward good ideas, but also includes making these ideas work in the field (Oukes, 2010). In 1980, the term "innovative behavior" was launched, which means the generation, promotion and understanding of new ideas within the framework of the work role, work groups or organization in order to benefit from the performance of roles, group or organization, although innovation is closely related to innovation, but the Inventive behavior involves more than being innovative (Dorner, 2012). As it serves as a positive attitude and contribution to employees who go beyond their job duties or obligations (Noerchoidah et al., 2020).

The concept of innovative behavior has attracted the attention of many researchers and writers, and there are many views on its definition. As (West & Farr, 1989) defined innovative behavior as all individual actions directed towards the generation, delivery and application of beneficial innovation at any organizational level (Babalola & Nigeroia, 2009). Whereas (Farr & Ford, 1990) defines innovative behavior as the behavior of an individual that aims to achieve the initiation and deliberate introduction (within the work role, group or organization) of new and useful ideas, processes, products or procedures(Jong & Hartog , 2010; Kheng et al., 2013; Leong & Rasli, 2014; Ramamoorthy & Flood , 2005). Innovative behavior from the point of view of is the act of generating, enhancing, and applying innovative thinking in an organization for the purpose of improving personal and organizational performance, which enables employees to use innovative ways of thinking, quickly and accurately to respond to changes in customer demand (Scott & Bruce, 1994). As for (Janssen, 2000), he sees that innovative behavior is a complex behavior that consists of three different behavioral tasks: generating ideas, promoting the idea, and implementing the idea (Janssen, 2000). Whereas, innovative behavior was defined by (Amo & Kolvereid, 2005) as an initiative of employees regarding the introduction of new processes, new products, new markets or such combinations within the organization (Gozukara & Yildirim, 2016). Innovative behavior can be defined from the point of view of Hsiao and colleagues (2011) as the worker's voluntary activities that exceed established role expectations (Hsiao et al., 2011: 31). Some researchers argue that innovative behavior is not just about developing new products in R&D environments, but also involves the entire organization, (Stoffers et al., 2015) defined it as a change associated with the creation and adaptation of new ideas that can be used at the global level or at the level of the organization (Stoffers et al., 2015). As for (Pukiene, 2016), he sees that innovative behavior is a multi-stage process that includes different behaviors that can be linked to distinct stages of the innovation process (Pukiene, 2016).

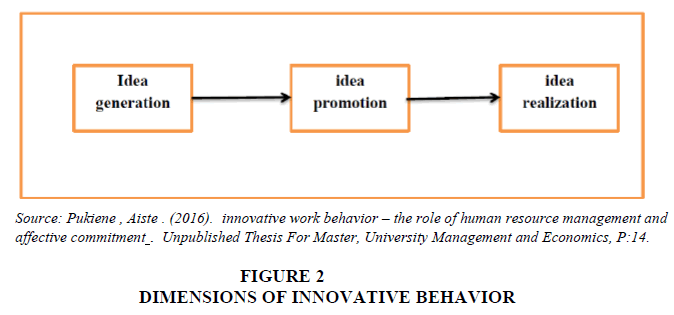

Dimensions innovative behavior

By reviewing what was written about the concept of innovative behavior, the researchers’ agreement about considering it a multi-stage process can be seen (Pukiene, 2016), And most researchers indicated that innovative behavior is a three-dimensional process, which is (Idea generation, idea promotion and idea realization) based on a study (Janssen, 2000), which was adopted in the current research. As shown in Figure (2) below:

Idea Generation

Innovative behavior begins with idea generation the creation of new and useful ideas in any field (Janssen, 2000); (Kanter, 1988) has shown that innovation usually causes the identification of a future horizon or a new problem that exists because of the existing need, and it is said that complexity and more relationships, openness to the environment, a large amount of information, and more entrances to the problem is necessary to generate new ideas or Approved solutions that stimulate innovation (Pukiene, 2016), Business problems, inconsistencies, gaps, and emerging new trends are key triggers for unique ideas, As both (Jong & Hartog) explained that good idea generators are individuals who can address problems or performance gaps from a different angle (Janssen, 2000).

The generation of ideas is a necessary condition for innovation as precedes the exploitation of opportunities, as Kanter 1998) emphasized that awareness of the need (opportunity), which is the first part of innovation, and the ability to build new ways to meet the need is the second part, and it seems that the key to generating the idea is the collection and reorganization of information and existing concepts of problem solving or performance improvement (de Jong, 2007).

Promoting Ideas

After generating ideas comes the second task, which is to promote ideas. When the idea is generated, the person who generated this idea will seek to find friends, supporters, or parties supporting the idea, or build alliances of supporters (Janssen, 2000). When they find supporters or allies for those ideas, new ideas that have not yet been implemented in the organization will be reinforced, as the focus is on seeking appropriate support and creating coalitions in the organization in order to persuade them to become part of the innovation process (Kroes, 2015).

So at this stage the idea is promoted throughout the organization with the aim of finding more support when implementing, as well as in order to enhance the success of the idea, as (Janssen, 2000) sees that the innovative factor has to engage in the community and search for friends, supporters and sponsors and in order to build alliances and defend For the idea to succeed, the innovator must be confident in the idea’s success, be consistent, and choose the right people to support the idea, which can include managers, members of other departments or close colleagues. These influential allies will provide the necessary strength behind him (Pukiene, 2016).

Idea Realization

The final stage of innovative behavior is the idea realization, that is, the conversion of innovative ideas into actual valuable results. When the idea is created and finds support, it must be implemented and put into practice. Therefore, this stage of the inventive behavior represents the completion of the idea by turning it into a useful application (physical or intellectual) that can later be transferred to others (Pukiene, 2016). Recognizing ideas requires the need for significant effort and a results-oriented attitude to make ideas happen, and idea realization also involves making innovations part of normal daily work processes and behaviors (Jong et al., 2010). There are a number of organizational issues such as bureaucracy, resource scarcity, and unskilled workers that have to be overcome in order to successfully turn those innovative ideas into valuable results. Individuals working can supplement some simple innovations in order to pave the way for more complex improvements to be successfully accomplished. These innovations require teamwork. With workers of different skills, knowledge, abilities and competencies and that the recognizing ideas is one of the most challenging behaviors than the innovation process because it requires different skills and knowledge and communication with other colleagues or even departments (Pukiene, 2016).

Study Methodology and Procedures

The Sample

The study community consists of all technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat (Technical Institute of Al Diwaniyah, Technical Institute of Najaf, Technical Institute of Kufa, Technical Institute of Karbala, Technical Institute of Babylon, Technical Institute of Samawah, Technical Institute of Musayyib).

As for the sample that could be reached, it was represented by the teachers of technical institutes holding high degrees. The questionnaire was distributed to the teachers in the technical institutes mentioned above. Because of cases of apology or incomplete cases and not suitable for analysis, the study used (453) a questionnaire only for the purposes of analysis, Table (1) shows the number of participants from each of the Middle Euphrates Technical Institutes. It is noted that the highest participation rate was from the Musayyib Technical Institute, while the lowest participation rate was from the Rumaitha Technical Institute.

| Table 1 Number Of Participants And Their Ratios According To Technical InstituteS |

||

|---|---|---|

| Technical Institute | Number of participants | Percentages |

| Technical Institute of Al Diwaniyah | 51 | 14% |

| Technical Institute of Najaf | 53 | 13% |

| Technical Institute of Kufa | 48 | 4% |

| Technical Institute of Karbala | 69 | 13 % |

| Technical Institute of Babylon | 130 | 27% |

| Technical Institute of Samawah | 27 | 8 % |

| Technical Institute of Musayyib | 75 | 18% |

| Total | 453 | 100% |

As seen in Table 2, the characteristics of the research sample in terms of age, gender, years of service and academic achievement. Frequencies and percentages were extracted to describe the research sample.

| Table 2 The Characteristics Of The Research Sample |

||

|---|---|---|

| Percentages | Frequencies | The level |

| Age | ||

| 17.20% | 78 | 23-35 |

| 60.40% | 274 | 48-36 |

| 17.80% | 81 | 61-49 |

| 4.40% | 20 | 74-62 |

| 100% | 453 | Total |

| Gender | ||

| 63.70% | 289 | Male |

| 36.20% | 164 | Female |

| 100% | 453 | Total |

| Tenure | ||

| 5.70% | 26 | 1-Oct |

| 11% | 50 | 20-11 |

| 38.80% | 176 | 30-21 |

| 34.80% | 158 | 40-31 |

| 9.40% | 43 | 41 - |

| 100% | 453 | Total |

| Education | ||

| 18.30% | 83 | Higher Diploma |

| 44.50% | 202 | Master's |

| 37% | 168 | PhD |

| 100% | 453 | Total |

As shown by the table, the most frequent age of the research sample was within the age group (48-36), and it was also found that the predominant proportion of the research sample was males, while the percentage of females was the least, either the number of years of service, the repetitions showed that the group of (21) to (30) years is the dominant category in the research sample, and the highest percentage of certification was for a master's degree.

Measuring Tool

Workplace ostracism

The researcher used 10- items from the scale Ferris et al. (2008) to measure the workplace ostracism variable according to a scale of (strongly agree) - (strongly disagree) and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this variable reached (0.899), which indicates the presence of internal consistency in the answers of a sample Find the direction of this scale.

Innovative behavior

It was based on the (Janssen, 2000) scale to measure the innovative behavior variable, which includes three dimensions (idea generation, idea promotion, idea realization). This scale consists of (9) items, three items for each dimension of the variable dimension. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for each dimension was (0.922-0.896-0.935) indicating the presence of internal consistency in the answers of the research sample towards this scale.

Test measures

Before performing the data analysis, the study used confirmatory factor analysis to test the reliability of convergent and discriminate of the measures employed in this study, The results of the confirmatory factor analysis showed that The measurement model of the current study fits well with the data withdrawn from the sample as shown in Tables (3,4).

| Table 3 Standard Saturations And Quality Of Conformance Statistics For Workplace Ostracism Scale |

||

|---|---|---|

| Indicators of Quality of Conformity | Standard Saturations | Pointer |

| 0.865 | WO1 | |

| 0.869 | WO2 | |

| Fit statistics | 0.861 | WO3 |

| Chi-square= 70.23 | 0.822 | WO4 |

| (df = 20) | 0.414 | WO5 |

| RMSEA= 0.032 | 0.852 | WO6 |

| GFI=0.93 | 0.859 | WO7 |

| NFI=0.94 | 0.855 | WO8 |

| CFI= 0.96 | 0.821 | WO9 |

| 0.852 | WO10 | |

| Table 4 Standard Saturations And Quality Of Conformance Statistics For Innovative Behavior Scale |

||

|---|---|---|

| Indicators of quality of conformity | Standard Saturations | Pointer |

| Idea generation | ||

| Fit statistics | 0.988 | GENE1 |

| Chi-square= 822.89 | 0.826 | GENE2 |

| (df =269 ) | 0.632 | GENE3 |

| RMSEA= 0.019 | Idea promotion | |

| GFI= 0.91 | 0.799 | PROM1 |

| NFI=0.92 | 0.911 | PROM2 |

| CFI= 0.98 | 0.796 | PROM3 |

| Realization idea | ||

| 0.971 | IMPL1 | |

| 0.866 | IMPL2 | |

| 0.984 | IMPL3 | |

Descriptive statistics and Hypothesis Test

Descriptive statistics

Table 5 presents the statistical description and correlation matrix for the study variables, as it is noted through the average, the workplace ostracism variable was close to a moderate level and the innovative behavior variable was within a high level. The standard deviation indicates the consistency of the answers received towards these variables, On the other hand, the correlation coefficients matrix shows the presence of negative correlations with statistical significance at the level (1% or (5%) among most of the study variables, and this provides initial support for the study’s hypotheses.

Hypothesis Test

H1: (which states that (there is a statistically significant inverse relationship between workplace ostracism and innovative behavior in its dimensions (idea generation, idea promotion, idea realization).

Through the results shown by the correlation matrix in Table (5), it is clear that there is a strong negative correlation between the workplace ostracism variable and innovative behavior with a correlation coefficient (-0.582*) at a significant level (0.05), There is also a strong negative correlation between the workplace ostracism variable and the dimensions of innovative behavior (idea generation, idea promotion, idea realization) and correlation coefficients (-0.392*, -0.211**, -0.364*) respectively at a significant level (0.01-0.05). This supports the validity of the first main hypothesis.

| Table 5 Description Of Statistics And Correlation Analysis N (453) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO | IB | GENE. | PROM | IMPL. | |

| WO | 1 | ||||

| Sig. | |||||

| IB | -0.582* | 1 | |||

| Sig. | 0.03 | ||||

| GENE. | -0.392* | 0.441** | 1 | ||

| Sig. | 0.03 | 0.00 | |||

| PROM. | -0.211** | 0.462** | 0.335* | 1 | |

| Sig. | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||

| IMPL. | -0.364* | 0.571* | 0.511** | 0.412* | 1 |

| Sig. | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |

| Mean | 3.077 | 3.825 | 3.903 | 3.736 | 3.836 |

| SD. | 0.527 | 0.084 | 0.235 | 0.148 | 0.309 |

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. wo: workplace ostracism IB: Innovative behavior GENE.: idea generation PROM.: idea promotion IMPL.: ideas realization.

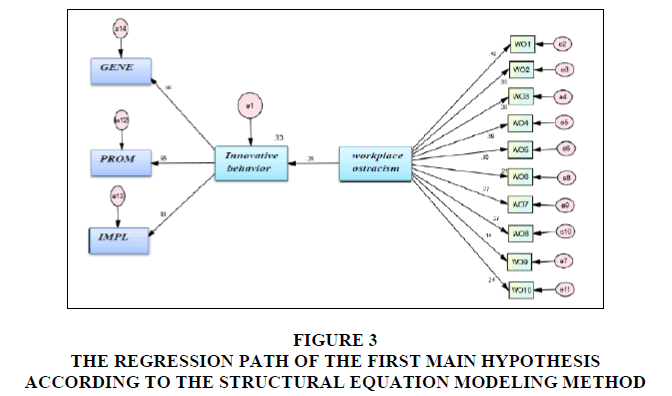

H2: Which states that (there is a significant inverse relationship between variable of workplace ostracism and the innovative behavior variable).

This hypothesis is concerned with testing the extent of the influence of the independent variable workplace ostracism on the dependent variable innovative behavior.

By observing Figure (3), it is clear that there is a significant negative impact of the workplace ostracism variable on the level of innovative behavior, and it is clear that the value of the standard effect factor has reached (-0.280), which means that the workplace ostracism variable adversely affects the variable Innovative behavior with a negative percentage (28%) at the level of technical technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat study sample, which means that changing one unit of deviation from the district in the workplace in technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat study sample will lead to a reverse change in innovative behavior with a negative percentage (28%) ), and this value is significant because the critical ratio (CR) value shown in Table (6) is (-0.975) a significant value at a significant level (P-Value = 0.01). As it is clear from Figure (3) that the value of the interpretation coefficient (R2) has reached (0.33) and this means that the interruption variable in the workplace explains the changes that occur in the innovative behavior by (0.33), while the rest is attributed to other reasons.

| Table 6 Impact Model Estimates Between The Workplace Ostracism Variable And The Innovative Behavior Variable |

|||||||

| Variable and dimensions | Path | Variable | S.R.W | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IB | <--- | WO | -0.280 | -0.233 | 0.047 | -0.975 | *** |

| GENE | <--- | IB | 0.978 | 1.060 | 0.013 | 79.127 | *** |

| PROM | <--- | IB | 0.959 | 0.861 | 0.015 | 57.423 | *** |

| IMPL | <--- | IB | 0.992 | 1.079 | 0.008 | 130.256 | *** |

| WO1 | <--- | WO | 0.433 | 0.414 | 0.051 | 8.184 | *** |

| WO2 | <--- | WO | 0.332 | 0.306 | 0.051 | 6.010 | *** |

| WO3 | <--- | WO | 0.383 | 0.355 | 0.050 | 7.064 | *** |

| WO4 | <--- | WO | 0.391 | 0.358 | 0.049 | 7.247 | *** |

| WO5 | <--- | WO | 0.350 | 0.325 | 0.051 | 6.365 | *** |

| WO7 | <--- | WO | 0.266 | 0.247 | 0.052 | 4.712 | *** |

| WO6 | <--- | WO | 0.214 | 0.225 | 0.060 | 3.736 | *** |

| WO8 | <--- | WO | 0.269 | 0.288 | 0.060 | 4.768 | *** |

| WO9 | <--- | WO | 0.143 | 0.150 | 0.061 | 2.458 | *** |

| WO10 | <--- | WO | 0.239 | 0.256 | 0.061 | 4.191 | *** |

Source: Prepared by the researcher based on the outputs of the Amos program. V.23

Figure 3: The Regression Path Of The First Main Hypothesis According To The Structural Equation Modeling Method.

Three sub-hypotheses emerge from it:

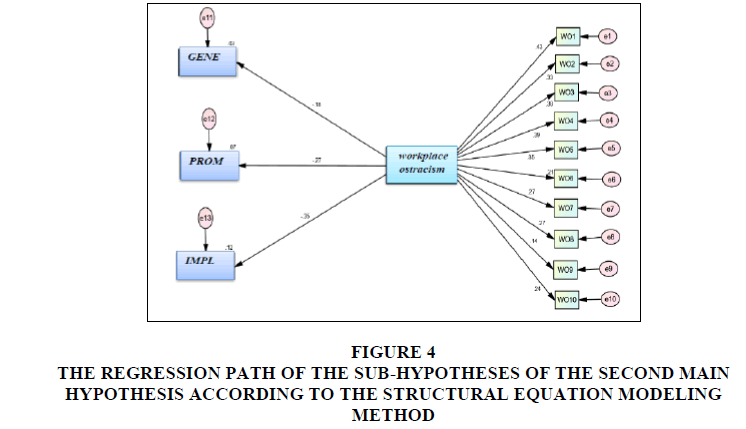

H21: There is a negative, significant effect of workplace ostracism variable and generating ideas.

By noting Figure (4). It is evident that there is a significant negative impact of the workplace ostracism variable and generating ideas, as it is clear that the value of the standard effect factor has reached (-0.182), and this value is considered significant because the value of the critical ratio (CR) shown in Table (7) is (-0.149). Significant value at a significant level (P-Value = 0.01).

| Table 7 The Impact Model Estimates Between The Workplace Ostracism Variable And The Dimensions Of The Innovative Behavior Variable |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| variable and dimensions | Path | Variable | S.R.W | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P |

| Idea generation | <--- | WO | -0.182 | -0.136 | 0.043 | -0.149 | 0.002 |

| Idea promotion | <--- | WO | -0.271 | -0.245 | 0.051 | -0.797 | *** |

| Idea realization | <--- | WO | -0.352 | -0.320 | 0.050 | -0.420 | *** |

| WO1 | <--- | WO | 0.433 | 0.414 | 0.051 | 8.184 | *** |

| WO2 | <--- | WO | 0.332 | 0.306 | 0.051 | 6.010 | *** |

| WO3 | <--- | WO | 0.383 | 0.355 | 0.050 | 7.064 | *** |

| WO4 | <--- | WO | 0.391 | 0.358 | 0.049 | 7.247 | *** |

| WO5 | <--- | WO | 0.350 | 0.325 | 0.051 | 6.365 | *** |

| WO6 | <--- | WO | 0.214 | 0.225 | 0.060 | 3.736 | *** |

| WO7 | <--- | WO | 0.266 | 0.247 | 0.052 | 4.712 | *** |

| WO8 | <--- | WO | 0.269 | 0.288 | 0.060 | 4.768 | *** |

| WO9 | <--- | WO | 0.143 | 0.150 | 0.061 | 2.458 | *** |

| WO10 | <--- | WO | 0.239 | 0.256 | 0.061 | 4.191 | *** |

Source: Prepared by the two researchers, based on the outputs of the Amos program. V.23

H22: There is a significant negative impact workplace ostracism variable and the promotion of ideas.

By noting Figure (4). It is found that there is a significant negative impact of the workplace ostracism variable and promoting ideas, as it is clear that the value of the standard effect factor has reached (-0.271), and this value is considered significant because the value of the critical ratio (CR) shown in Table (6) is (-0.797) ) Significant value at a significant level (P-Value=0.01).

Figure 4: The Regression Path Of The Sub-Hypotheses Of The Second Main Hypothesis According To The Structural Equation Modeling Method.

H23: There is a negative, significant effect of workplace ostracism variable and idea realization.

By observing Figure (4), it becomes clear that there is a significant negative impact of the workplace ostracism variable and ideas realization , It is also clear that the value of the standard effect factor has reached (-0.352), and this value is considered significant, because the value of the critical ratio (CR) shown in the table (6) The amount of (-0.420) is a significant value at a significant level (P-Value = 0.05), as in the same table.

From the foregoing, it was found that all tracks had a negative effect on the dependent variable, and accordingly, this result provides total support towards accepting the sub-hypotheses.

Thus, it is possible to accept the second main hypothesis related to the existence of a negative influence between workplace ostracism and the variable of innovative behavior within the level of negative influence. This explains that when workers feel workplace ostracism, that is, they feel excluded and ostracized, this results in consequences, including a lack of personal and positive communication and lack of participation in work with others, and that individuals excluded by others may have aggressive behaviors and even less participation in behaviors Help or positive social behaviors, and this in turn will negatively affect the innovative behavior as it depends mainly on the participation of others in the ideas generation, ideas promotion and ideas realization.

Research Results and Recommendations

Results

1 The workplace boycott directly or indirectly affects the behavioral outcomes of employees (such as innovative behavior, job performance, organizational citizenship behavior, job withdrawal behavior...etc).

2 When the idea is generated, the person who generated this idea will seek to find friends, supporters, or parties supporting the idea, or build alliances of supporters to implement this idea. 3 The perceptions of the teachers in technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat see that the dimension of generating ideas is the most present dimension among the dimensions of innovative behavior, all of which obtained a high level, but the highest arithmetic mean was for the dimension of generating ideas, and this explains that the teachers are ready to accept and generate innovative ideas and turn them into Tangible actual results.

4 The results of the study showed that there is a negative relationship between the workplace ostracism and the innovative behavior, that is, when the workers feel the presence of the workplace ostracism, this will reduce the performance of the workers and their participation in the work.

5 The results of the study showed the existence of a significant influence relationship between workplace ostracism and innovative behavior, which means that changing one unit of deviation from boycott in the workplace in the technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat of the study sample will lead to an adverse change in innovative behavior with a negative percentage.

Recommendations

1 It is important for the administration of the technical institutes in AI Furat Al Awsat the study community to work diligently to limit the workplace ostracism and disrupt its causes by creating a culture that deters ostracism and disputes in the workplace and instilling a spirit of cooperation among workers.

2 Preparing a code of conduct and standards of professional conduct to guide the actions and behavior of employees and intensify awareness and education programmes.

3 It is necessary that the study sample organization seeks to develop the innovative behavior of the teaching staff by assigning the creative individual tasks that raise challenging motives to discover new ideas, promote them and actually apply them, and urge others to innovate.

4 Stimulating the creative behavior among the employees, financially and morally, and rewarding the positive behaviors shown by the employees, supporting them and urging them to do more in order to face challenges and problems.

References

Al-Atwi, A.A., Yahua, C., & Joseph, A. (2021). Workplace ostracism,paranoid employees and service performance:A multilevel investigation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(2), 1-17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Al-Atwi, A. (2017). Pragmatic impact of workplace ostracism: toward a theoretical model. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 26, 35-47.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Al-Jubouri, Ali. A., Fleifal, Ali, A., & Oglah, Hameed, M. (2020). The influential connection between knowledge hiding and workplace ostracism in Iraq. Ishtar Journal of Economics and Business Studies (IJEBS), 1(3), 1-16.

Aydin, O., Sahin, D., Yavuz, H., Yasemin, G., Alp , A., Kaya, G., & Ceylan S. (2013). The effects of the need to belong and being aware on reactions to psychological exclusion. Turkish Journal of Psychology, December, 28(72), 21-31.

Babalola, S.S., & Nigeria I. (2009). Women entrepreneurial innovative behaviour: The role of psychological capital. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(11), 184-192.

Balliet, Daniel, D., & Ferris, L. (2013). Ostracism and prosocial behavior: A social dilemma perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120, 298–308.

Beest, I.V., & Williams, D.K. (2006). When inclusion costs and ostracism pays, ostracism still hurts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 918–928.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bernier, L. (2014). Ostracism an often-overlooked form of workplace bullying, finds study. The National Journal of Human Management, (800), 387-5164.

Chen, R. & Song, J. (2019). Effect of workplace ostracism on counterproductive work behavior--- psychological contract breach as the mediator. International Journal of Business and Economics (UTCC IJBE).

Chen, Y., & Li, S. (2019). The relationship between workplace ostracism and sleep quality: A Mediated Moderation Model. Front Psychol, 10, 1-13.

Choi, Y. (2020). A study of the influence of workplace ostracism on employees’ performance: moderating effect of perceived organizational support. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 29(3), 333-345.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

De Jong, J.P.J. (2007). Individual innovation the connection between leadership and employees innovative work behavior. Dissertation For Doctoral, Universiteit van Amsterdam .

Dorner, Nadin, Innovative work Behavior: The roles of employee expectations and effects on job performance, (2012), Dissertation For Doctoral, university of st. gallen, school of management, economics.

Durrani, T., & Iftikhar, K. (2020). What leads to ostracism and its consequences, Thesis for Master, Luleå University of Technology Department of Business Administration, Technology and Social Sciences.

Ferris, D.L., Brown, D.J., Berry, J.W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 1348-1366.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fiset, J. (2014). The good shepherd: The Impact of Relational Leadership Interventionary Behaviour on Workplace Ostracism, degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Administration), Concordia University.1-307.

Goodacre, R., & Zadro, L. (2010). O-Cam: A new paradigm for investigating the effects of ostracism. Behavior Research Methods, 42(3), 768-774.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gozukara, I., & Yildirim, O. (2016). Exploring the link between Distributive Justice and Innovative Behavior: Organizational Learning Capacity as a Mediator. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 6(2), 61–75.

Haq, I.U. (2014). Workplace Ostracism and Job Outcomes: Moderating Effects of Psychological Capital, Human Capital without Borders: Knowledge and Learning for Quality of Life Proceedings of the Management, Knowledge and Learning International Conference 2014, Portorož, Slovenia, 1309-1323.

Hitlan, R.T., Cliffton, R.J., & Desoto, M.C. (2006). Perceived exclusion in the workplace: the moderating effects of gender on work-related attitudes and psychological health. North American Journal of Psychology, 8, 217-236.

Howard, M.C., Cogswell, J.E. and Smith, M.B., (2019). The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 577-596.

Hsiao, H.C., Chang J.C., Tu Y & Chen S.C. (2011). The impact of self-efficacy on innovative work behavior for teachers. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 1(1), 31-36.

Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness, and innovative work behavior. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 287-302.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jong, J.D., & Hartog, D.D. (2010). Measuring Innovative work Behavior. Measuring Innovative Work Behavior, 19(1), 23-36.

Khan, A., & Taimur, A. (2017). Workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs): Examining the Mediating Role of Organizational Cynicism and Moderating Role of Neuroticism, Master Of Science In Management Sciences, Capital University Of Science & Technology Islamabad.

Kheng, Y.K., June, S., & Mahmood, R. (2013). The determinants of innovative work behavior in the knowledge, intensive business services sector in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 9(15), 47-59.

Kroes, B. (2015). The relationship between transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of Self-Efficacy and the effect of perceived Organizational Support on Innovative work Behavior, Thesis for master, human resource studies faculty of social and behavioral sciences.

Kwan, H.K., Miaomiao, L., Wu, X., & Xiaofeng, X. (2021). The need to belong: how to reduce workplace Ostracism. The Service Industries Journal, 41, 1-23.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Leong, C.T., & Rasli, A. (2014), The Relationship between Innovative work Behavior on work role performance: An Empirical study. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 129, 592– 600.

Li, D., & Zhang, M., (2019), Are They Isolating Me? The Influence of Workplace Ostracism on Employees Turnover Tendency. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 376, 308-314.

Mcshane, S.L., & Glinow, M.A.V. (2005). Organizational Behavior, 3th ed., McGraw Hill lruuin , New york San Francisco .

Messmann, G. (2012). Innovative work behaviour investigating the nature and facilitation of vocational teachers’ contributions to innovation development, Dissertation For Doctoral, der University Regensburg.

Nezlek, J.B., Wesselmann, E.D., Wheeler, L., & Williams, K.D. (2012). Ostracism in everyday life. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 16(2), 91-104.

Noerchoidah, E.A., & Christiananta, B. (2020). Enhancing innovative work behavior in the hospitality industry: Empirical Research from East Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Business and Society, 21(1), 96-110.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Oukes, T. (2010). Innovative work behavior: A case study at a tire manufacturer. Thesis for master, university of twente.

Pharo, H., Gross, J., Richardson, R., & Hayne, H. (2011). Age-related changes in the effect of ostracism. Social Influence, 6(1), 22–38.

Pukiene, A. (2016). Innovative work behavior-the role of human resource management and affective commitment. Thesis for Master, University Management and Economics.

Ramamoorthy, N., & Flood, P.C. (2005). Determinants of innovative work behaviour: Development and test of an Integrated Model. Determinants of Innovative work Behaviour, 14(2), 142-150.

Robinson, S.L., O’Reilly, J., & Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at Work: An Integrated Model of Workplace Ostracism. Journal of Management, 39(1), 203-231.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rudert, S.C., Keller, M.D., Hales, A.H., Walker, M., & Greifeneder, R. (2019). Who gets ostracized?A personality perspective on risk and protective factors of ostracism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(6), 1-84.

Sao, R. & Wadhwani, K. (2018). Workplace Ostracism: More Distressing than Harassment. Helix, 8(6), 4167-4170.

Scott, S.G., & Bruce, R.A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A Path Model of Individual Innovation in the Workplace. The Academy of Management Journal, 37, 580–607.

Stoffers, J., Neessen, P., & Dorp, P. (2015). Organizational culture and innovative work behavior: A case study of a Manufacturer of Packaging Machines. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 5,198-207.

Vui-Yee, K., & Yen-Hwa, T. (2016). Workplace ostracism and turnover intention: A Moderated Mediation Model of Job Stress and Gender, Proceedings of 10th Asia - Pacific Business and Humanities Conference 22-23 February 2016, Hotel Istana, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ISBN: 978-1-925488-00-5.

Wan, E., Chan, K., & Chen, R., (2016). Hurting or helping? The effect of service agents’ workplace ostracism on customer service perceptions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (6), 1-58.

Wilk, G.M., & Bien, M.K. (2018). Ostracism in the workplace, in D’Cruz, P.,Noronha, E., Keashly, L. and Tye-Williams, S. (Eds), Special Topics and Particular Occupations, Professions and Sectors, Springer Nature, Singapore, 1-30.

Williams, K.D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence, New York: Guilford Press.

Wu, C.H., Liu, J., Kwong, K., Lee, C. (2015). Why and when workplace ostracism inhibits organizational citizenship behaviors: an organizational identification perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Received: 07-March-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23-13284; Editor assigned: 08-March-2023, PreQC No. AEJ-23-13284(PQ); Reviewed: 20-March-2023, QC No. AEJ-23-13284; Revised: 22-March-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23-13284(R); Published: 25-March-2023