Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education in Public Institutions of Learning in the Province of Kwazulu-Natal

Thandukwazi R Ncube, Durban University of Technology

Lawrence Mpele Lekhanya, Durban University of Technology

Citation Information: Ncube TR, Lekhanya LM. (2021). Evaluation Of The Effectiveness Of Entrepreneurship Education In Public Institutions Of Learning In The Province Of Kwazulu-Natal. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(7), 1-18.

Abstract

Individuals around the world are finding that entrepreneurship is an avenue to create wealth, stimulate economies, and fulfil self-employment dreams. Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education are on the rise in South African Higher institutions of learning since most institutions are on the verge of embedding it into their curriculum as one of the graduate attributes. Considering the shifting entrepreneurial environment, teachers must constantly be adjusting the educational practices, procedures, and curriculum to ensure the best outcomes for future entrepreneurs. Public institutions of learning need to entice students through programmes that are relevant in order to ensure the success of their new ventures. As the entrepreneurial environment has changed, so have the expectations of educational programmes. This study evaluates the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in public institutions of learning (PIL) (technical vocational education and training institutions, universities of technologies, and universities). It aims to examine the competencies that are needed to successfully start a business endeavour and the current level of skills these institutions offer to students for business and entrepreneurial programmes. The study also provides suggestions for new approaches in teaching pedagogies that adjust to the changes in the business environment of the country.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurship Education, Self-employment

Introduction

The time has come to consider what public institutions of learning (PILs) (technical vocational education and training institutions, universities of technologies, and universities) can do to reduce unemployment and help the poor by taking what they do best, namely, education, and applying it to one of the most effective mechanisms for economic growth and empowerment, namely, entrepreneurship (Chris, 2017). Entrepreneurship is a vehicle for increasing employment and generating economic growth, especially in developing countries (Ncube & Zondo, 2018; Waghid, 2019; Kariv et al. (2019); (Littlewood & Holt, 2018); Marsh, 2019); (Asghar et al., 2019). Educational institutions in South Africa have a role to play in preparing entrepreneurs. The motivation to start a business should be communicated through all the curricula of the university so that all students are exposed to this, not only those specifically registered for business of entrepreneurship related degrees. The goal is to increase the frequency and number of start-ups by improving the entrepreneurial skills and motivation of all students.

The South African Technology Network (SATN) highlights the need to embed graduate attributes, more specifically “entrepreneurship education”, into the curricula of PIL and thereby stimulate South Africans’ entrepreneurial and innovative capabilities. According to Belitski & Heron (2017); Ustav & Venesaar (2018), entrepreneurship education is one of the major forces that can determine the development of an economy. Therefore, it is necessary to cultivate the entrepreneurial mind-sets of young people in order to create a more favourable climate for entrepreneurship, as South Africa is not taking advantage of its entrepreneurial potential (Bauman & Lucy, 2019). Waghid (2019) emphasised that public institutions of learning have an important role to play in improving the entrepreneurial key competence of SA’s graduates.

Research Problem

Entrepreneurship plays a role in the economic performance of every country (Ramchander, 2019) as it has the ability to generate job opportunities improve unemployment and provide goods and services for the benefit of society (Mustapha & Selvaraju, 2015; Bauman & Lucy, 2019). For these reasons South Africa, as a developing country, has emphasised entrepreneurship education and its role in development of a viable economy (Herrington et al., 2010; Botha & Bignotti, 2017). In South Africa the problem of graduate unemployment has become a major issue (Chimucheka, 2014). There has been an increase in the number of public and private higher education institutions and the number of students enrolled, which has resulted in a huge increase in the number of graduates, meaning, inevitably, that a large number of graduates will be unsuccessful in their job searches (Mashau et al., 2019). Development of entrepreneurial skills can change this by producing job providers and not just job seekers (Ahmad & Buchanan, 2015). Thus, PILs in South Africa need to nurture the development of entrepreneurial skills among their students (Oluwajodu et al., 2015). Harrington and Maysami (2015) emphasised that early exposure to entrepreneurial studies, is an essential consideration in developing successful entrepreneurs.

Some authors point out that colonial approaches to education still have an impact on the current trend of entrepreneurship education (Wilson & Alebeek, 2017; Littlewood & Holt, 2018). During the colonial era students were trained largely to fill gaps in the type of employees needed at the time meaning that students were educated with a view to the available labour market rather than as entrepreneurs (Chimucheka, 2014; Wilson & Alebeek, 2017).

Primary Objective of the Research

The research evaluates the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in public institutions of learning in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Secondary Objectives

To achieve the primary objective, the study explored the following:

1. Whether the entrepreneurship education curricula offered in public institutions of learning promote business start-ups.

2. The perceptions of educators regarding the benefits and effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in society.

Literature Review

Concepts of Entrepreneurial Education

Entrepreneurship is a world-wide phenomenon that is positively influencing economic growth by means of stimulating the emergence of new and innovative business start-ups (Akhuemonkhan et al., 2013; Robb & Valerio, 2014; Waghid, 2019). Entrepreneurship education is important for entrepreneurial students to acquire competencies that give them sureness to operate in any environment.

According to Bagheri & Lope Pihie (2013), an entrepreneur is an innovative individual who has developed a business where there was no such business before. Elmuti et al. (2012) quote Schumpeter (1951) as follows:

An entrepreneur is a person or persons who holds the skill to identify and evaluate business opportunities, amasses the necessary resources to take advantage of them and takes appropriate action to ensure success.

According to Voda & Florea (2019), entrepreneurs are people who continually discover new markets and try to figure out how to supply those markets efficiently and make a profit. They are individuals who are able to exploit change and convert this into business opportunities (Mustapha & Selvaraju, 2015; Rahn et al., 2015). Early French, British and Austrian economists wrote admiringly of entrepreneurs as being “The change agents of progressive economies” (Ojeifo, 2013).

Schumpeter was an Austrian economist based at Harvard University who pronounced that entrepreneurship was a “force of creative destruction” which destroyed the conventional way of doing things through the creation of new and better ways (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). Criaco et al. (2017) defined entrepreneurship as a process and entrepreneurs as innovators who use the process to change the status quo through new combinations of resources and new methods of commerce. Littlewood and Holt, (2018) stated:

The spirit of entrepreneurship lies in the perception and exploration of new opportunities in the realm of business. It always has to do with bringing about a different use of national resources in that they are withdrawn from their traditional employ and subjected to new combinations.

According to Hisrich and Peters (1992), innovations that are successful and produce an increase in economic activity generally exhibit the following characteristics:

1. Introduction of new goods;

2. Introduction of a new method of production;

3. The opening of a new market;

4. The conquest of a new source of raw material; and

5. The creation of a new type of industrial organisation (Hisrich & Peters, 1992).

There are broader definitions of entrepreneurship too, covering social, public and corporate forms of entrepreneurship (Valerio et al., 2014; Harrington & Maysami, 2015; Abella, 2016). This indicates that entrepreneurship not only includes business undertakings, but also an individual’s approach to life.

The Importance Self-Employment

There are many descriptions of self-employment (Akinbami, 2015; Santhosha, et al., 2015). However, the description by Iwu et al. (2019), contains the basic common elements, and forms the basis for use of the term in this study. According to these authors, a self-employed person is someone who does not earn their income from being employed by another individual or organisation, but through their own elf-managed economic activity. Thus, in the context of this study, the term “self-employed graduate” refers to people who have completed their university education in any discipline and have chosen to start their own businesses which they will own and from which they will derive their primary income (Iwu et al., 2019).

The term “entrepreneurship” has a larger meaning than merely starting a business (Ramchander, 2019). Thorgren & Omorede (2018) state that this term can include other types of activities as well, such as social and public enterprises (Thorgren & Omorede, 2018 Cho & Honorati, 2014). The differences between such enterprises are that economic entrepreneurship is the creation of a business in order to make a profit. A social enterprise may also make a profit, but such profit is orientated towards creating social value (Thorgren & Omorede, 2018). Public enterprises are orientated towards helping public officials be more efficient in the provision of services (Solomon et al., 2019). There is a notion too of “corporate entrepreneurship” which refers to the application of entrepreneurial culture in the form of innovation and modern technology so as to improve the function and services of companies (Pitso, 2019). In this sense, entrepreneurship can be applied and integrated in different undertakings. Thus, “entrepreneurship” is an economic and social phenomenon (Fayolle & Gailly, 2008; Akhuemonkhan et al., 2013; Baldry, 2015).

Entrepreneurial Education Intentions

Regarding entrepreneurial education intention, Abella (2016) makes the following observation:

Despite the varying definitions of entrepreneurship and the absence of one commonly accepted definition of the term, all the accepted definitions revolve around the concept of initiating or attempting to start up a business.

According to Rauch and Hulsink (2015), “intention” is a state of mind (a mind-set) which guide’s an individual’s focus in a particular direction in order to accomplish desired goals. Entrepreneurial intention can therefore be understood as being the decision an individual makes in the present about starting their own business sometime in the future (Pruett, 2012; Bignotti & Le Roux, 2016; Sánchez, 2013).

Intentions are a bridge between beliefs and subsequent behaviour (Fayolle & Gailly, 2015; Jayeoba, 2015). Thus, individuals form attitudes towards a particular behaviour based on their perception (beliefs) of the consequences of enacting such behaviour and the existing normative beliefs about such behaviour (Belitski & Heron, 2017). In this way attitudes drive behaviour (Eggers et al., 2010), and without intentions action is less likely (Rauch & Hulsink, 2015; Jayeoba, 2015; Jabeen et al., 2017). (Rauch & Hulsink (2015) make an interesting observation that individuals can experience key moments of motivation that radically transform their heart and mind which cause them to consider becoming an entrepreneur or job creator. Robb and Valerio (2014) echo this when they observe that entrepreneurial philosophies are fuelled by motivation, but intentions are required for the idea to be concretised. Rauch & Hulsink (2015) point out that the term “entrepreneurial intention” has a similar meaning to other terms such as entrepreneurial awareness, entrepreneurial potential, aspiring entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial proclivity, entrepreneurial propensity and entrepreneurial orientation. In this study, the term “entrepreneurial intention” is used.

Belitski and Heron (2017) list certain factors which they regard as influencing whether an individual acts entrepreneurially or not:

1. Perceived ability to execute the entrepreneurial behaviour;

2. Attitude (negative or positive) towards entrepreneurial behaviour; and

3. Subjective and social norms (the perceptions of others regarding entrepreneurship, the level of motivation and social support systems).

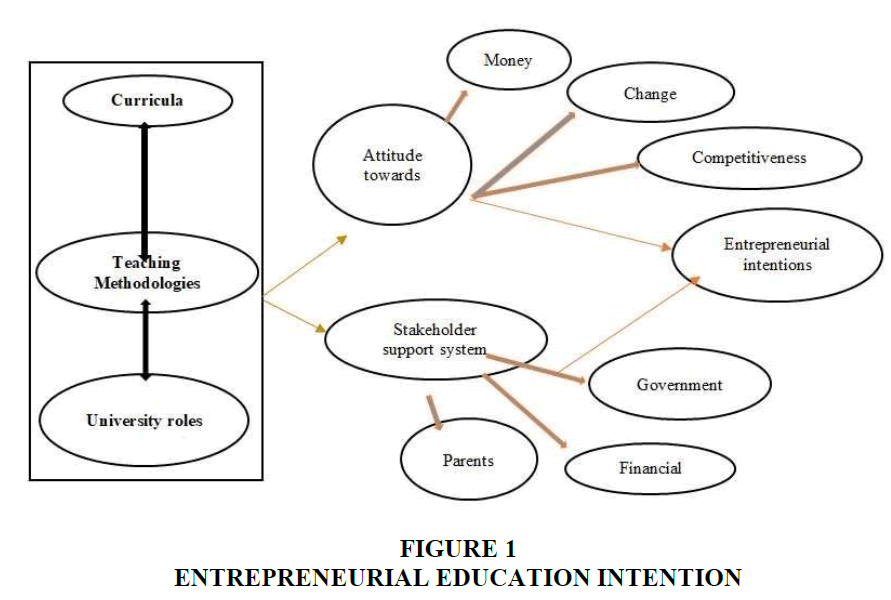

Factors such as these can be inspired by personality characteristics as well as education (Memani & Fields, 2014). Factors affecting entrepreneurial education intention are outlined in Figure 1 (Source: Adopted from Rauch & Hulsink (2015)) below.

Entrepreneurial Education on Self-Efficacy

Entrepreneurship education and training plays an important role in developing entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) (Pruett, 2012). According to Chimucheka (2014), the term “self-efficacy” refers to the subjective perception of an individual regarding their capacity to follow through on the type of behaviour required to execute a particular performance. Thus, selfefficacy affects the degree to which a person can become aware of opportunities in the environment and act on them; therefore education about self-efficacy is a prerequisite in entrepreneurship education (Fayolle & Gailly, 2008; Akinbami, 2015).

Chuanyin and Jin (2014) found that that entrepreneurial education and training does result in ESE and the intention to start a new business enterprise. Robb and Valerio (2014) found those facilitating students’ self-confidence, general knowledge and self-efficacy; entrepreneurship education can increase students’ perceptions of the possibility that they could pursue an entrepreneurship path. Self-efficacy grows over time as entrepreneurs reflect on and learn from experience (Fulgence, 2015b). Therefore, entrepreneurship training must focus both on technical knowledge as well as developing the self-confidence of potential entrepreneurs in order to facilitate entrepreneurship intention.

The Importance of Entrepreneurial Education for South Africa’s Economic Development

The correlation between economic growth and entrepreneurship is positive (Akhuemonkhan et al., 2013; Cassim et al., 2014; Harrington & Maysami, 2015; Robb & Valerio, 2014). However, there are many bureaucratic challenges, complexities and expenses in government policies and regulations that affect entrepreneurship in a number of countries, particularly emerging economies (World Bank, 2013). According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) 2015 Global Report (GEM, 2015), in the Total Entrepreneurship Activity Index (TEA) South Africa is ranked below average in entrepreneurship activity along with countries such as Croatia, Poland and Hungary. South Africa is an emerging economy therefore is in need of focus on the development of entrepreneurial skills and abilities as well as the development of suitable policies (Herrington et al., 2015; Littlewood & Holt, 2018). Cassim et al. (2014) state that in South Africa there has been an improvement in the regulatory environment in recent years.

The role of entrepreneurship and an entrepreneurial culture in development of the economy and society is vital (Ojeifo, 2013; Harrington & Maysami, 2015). The creation of a business is a vital aspect of entrepreneurship, but entrepreneurship goes beyond that. It also includes the ability to identify opportunities, take calculated risks, as well as having the zeal to carry out an idea from conception through to its maturity phase (Ojeifo, 2013; Ncube & Zondo, 2018). Entrepreneurs through their activities open up new markets and create jobs in the process (Akhuemonkhan et al., 2013). They transform ideas into practical economically functional enterprises (Cho & Honorati, 2014). According to Robb and Valerio (2014), “entrepreneurs are smart risk-takers, implementers, rule-breakers and innovators”.

The Relevance of Entrepreneurship Education to Economic Growth

Entrepreneurship is a solution to low economic growth as well as unemployment and poverty, therefore entrepreneurship education is important (Harrington & Maysami, 2015; Chuanyin & Jin, 2014; Ncube, 2016). Harrington & Maysami (2015) state that entrepreneurship is essential for economic growth and development in modern open economies. The phenomenal growth and advance of information and communication technology has opened up space for entrepreneurship because it facilitates niche services and allows global reach (Wu et al., 2018).

It is evident that entrepreneurship can positively influence economic growth and development therefore governments should support entrepreneurship educational programmes in order to increase the supply of entrepreneurs (Cassim et al., 2014). Two reasons for students to study entrepreneurship are that this will help them set up their own businesses and also that the knowledge and skills gained will be relevant in any setting within larger organisations as well (Maimane, 2016).

Strategies for Effective Entrepreneurship Education

Robb & Valerio (2014) are of the view that human talent is the most useful element in today’s knowledge economy. Education and training therefore, are also necessary elements. Therefore, (Ojeifo, 2013) posits that focusing on the advancement of entrepreneurship education can produce a skilled workforce and help graduates find suitable jobs or embolden them to set up their own business ventures. The following strategies are proposed by Cho & Honorati (2014) can help to alleviate the problem of the lack of entrepreneurship education in South Africa:

1. There should be some form of genuine schoolwork-based learning incorporated in some studies as part of the national economic development strategies. The development of an apprenticeship scheme would give new graduates some work skills and experience;

2. Pool local public and private funds to create a small venture capital fund;

3. Introduce school-based enterprises where students identify potential businesses plan, create and operate small businesses using the school as mini incubators;

4. Provide small business schools where interested students and community members can participate.

5. Develop entrepreneurship internship programmes, matching students with locally successful entrepreneurs with clearly established education programmes;

6. Establishing an enterprise college aimed at fostering the specific skill sets required for entrepreneurship to serve as skill acquisition centres for the youth;

7. Creating an economic friendly political environment; and

8. Improving on the government’s taxation of small-scale businesses.

The Importance of Entrepreneurial Education

Entrepreneurship education can be nurtured and learnt. Acquiring competence as an entrepreneur is more significant than simply receiving financial resources and consulting support (Chimucheka, 2014; Boi, 2018). Entrepreneurship education creates the kind of mind-set that can influence a person's intention and behaviour to venture into business (Memani & Fields, 2014). Mustapha & Selvaraju (2015) propose that people who have been exposed to entrepreneurship education have a greater inclination to establish entrepreneurial ventures. Thus, entrepreneurship education can influence students to decide on entrepreneurship as a career path. On this basis, Chimucheka (2014) claims that “The number of graduate entrepreneurs will therefore likely increase if more students are exposed to entrepreneurship education programmes and activities at university”. Curricula should be designed to enhance the entrepreneurial characteristics related to previous work experience and by means of enterprise education models (Claudia, 2013).

Entrepreneurial education aims to develop the skills and characteristics that can encourage individuals to develop new and innovative plans (Mustapha & Selvaraju, 2015), and to understand the linkages between their businesses and other sectors of the economy and society (Taatila, 2010). Harrington and Maysami (2015) point out those employers seek out students who can act entrepreneurially as they are more able to deal with the range of dynamics found in business environments.

Entrepreneurship is a Key Driver of the Economy

Many small businesses that have been initiated by entrepreneurs go on to create big businesses that increase jobs and wealth (Ncube, 2016). Entrepreneurship promotes creativity, self-esteem and a greater sense of personal agency. This type of culture can maximise individual and collective economic and social success locally, nationally and globally (Chimucheka, 2014). The National Content Standards for Entrepreneurship Education (e.g. the process and traits/behaviour associated with entrepreneurial success) have been developed in order to prepare youth and adults to succeed in an entrepreneurial economy (Lahn & Erikson, 2016; Ondiba & Matsui, 2019).

Entrepreneurship Education Is a Lifelong Learning Process

Entrepreneurship education starting from primary school and continuing through to tertiary and adult education can increase knowledge and competence thereby also improve individuals’ and communities’ quality of life (Spencer et al., 2012). The National Content Standards and their supporting Performance Indicators (that is, measurable value that validates how effectively the PILs are achieving key entrepreneurship education objectives) is a framework for teachers to build appropriate objectives, learning activities and assessments. Using this framework, students can gain the insight and expertise they need to set up their own businesses (Ojeifo, 2013).

Roles of Entrepreneurship Education in Economic Empowerment and Development in SA

According to Gordon and Bursuc (2018), an entrepreneurship education should be able to excite and equip students with entrepreneurial skills and in this way shift the perceptions of students from paid employment to self-employment. This perception dates from the colonial era when education and training was designed to prepare people to work for their colonial masters in paid employment (Akinbami, 2015).

Entrepreneurship education, according Chuanyin & Jin (2014); Henry & Lewis( 2018) have the ability to equip and make students experts in the production of certain items. Entrepreneurship education can be designed such that individuals can channel their creative abilities and skills to their areas of interest, for example, crafting, sewing, farming, manufacturing, mining, computers, information technology, retail, entertainment, catering and so on (Akinbami, 2015; Chuanyin & Jin, 2014; Henry & Lewis, 2018; Ismail et al., 2018). South Africa’s future entrepreneurial capacity depends on how well the nation is equipping individual citizens to start their own businesses and to be able to provide employment, not only for themselves but also for others (Cassim et al., 2014).

Methodology

Target Population and Units of Analysis

The target population was all final year students and teachers/academics involved in business studies at schools and tertiary PILs in KZN province. Purposively selected public tertiary institutions in KZN were included in the study as well as three selected secondary schools. Purposive sampling was based on the researcher’s judgement of who could provide the specialised knowledge and experience required to gain information-rich data related to the topic under investigation (Plano Clark, 2017; Shorten & Smith, 2017; Reio & Werner, 2017). A total of 256 questionnaires were distributed but only 223 responses were received (that is, 136 final year students and 87 teachers in public institutions of learning) giving an 85.1 percent response rate; 5.1 percent above the expected response based on the pilot survey, which yielded an 80 percent response. According to Sekaran & Bougie (2016), an 80 percent response rate is good to claim representativeness of response to the sample. The participants were drawn from schools, TVETs, universities of technology and universities operating as PILs.

A literature review was conducted in order to establish a theoretical base for the empirical study. The method of empirical research was in the form of two questionnaires designed by the researcher and based on the literature review. The first questionnaire was distributed to purposively select final year students in public institutions of learning. Final year students were selected specifically as they experience the effects of school education in public institutions of learning shortly after graduating (some struggle to secure jobs whilst some fail to start their own small businesses.

Research Findings

This chapter presents the results and discusses the findings related to the data collected (quantitative and qualitative). A survey was conducted with 16 respondents from each participating public institutions of learning in the province of Kwa-Zulu Natal in South Africa. A total of 256 questionnaires were distributed but only 223 responses were received (that is, 136 final year students and 87 teachers in public institutions of learning) giving an 85.1 percent response rate; 5.1 percent above the expected response based on the pilot survey, which yielded an 80 percent response. According to Sekaran & Bougie (2016), an 80 percent response rate is good to claim representativeness of response to the sample. The participants were drawn from schools, TVETs, universities of technology and universities operating as PILs.

Quantitative Data - Teaching Staff

Assessment of Whether an Entrepreneurship Education Curriculum Promotes Business Start-Up Effective Entrepreneurship Education Offers Students Access to The Skills and Knowledge Needed to Start an Entrepreneurial Venture

The majority of respondents (87.4%) were in agreement with the statement (agreed = 50.6%; strongly agreed = 36.8%), 10.3% were neutral, and 4.3% disagreed (disagree = 2; strongly disagree = 2.3). The results reveal that (x2 = 53; df = 3; P = 0.000), which means that there is a correlation between entreptreneurship education and the skills needed for business start-up. Bauman and Lucy (2019) contend that entrepreneurship education promotes entrepreneurial knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours, and Farny et al. contend that graduates of such programmes are are ablew to acquire creative and innovative skills and be able to identify opportunities and create new businesses.

The Entrepreneurship Education Curriculum in the Institution is Designed to Equip Students with the Skills Needed to Start up Their Own Businesses

A total of 73.6% (agree = 50.6%; strongly agree = 23%) of respondents agreed with the statement that the entrepreneurship education curriculum in the institution is designed to equip students with the skills needed to start up their own business, 20.7% were neutral, and 5.7% disagreed (strongly disagree = 4.6%; disagree =1.1%). The findings reveal that the majority of teachers believe that the existing entrepreneurship curriculum equips students with enough skills to start-up their own ventures. The findings are in agreement with the statement by Ismail et al., (2018) that entrepreneurship education can train particular skills and improve the chances of performing the related behaviour. The findings are supported by a Chi-square test that was conducted to determine if the entrepreneurship education curriculum in PILs equips students with the skills needed to start-up their own ventures. The results reveal that (x2 = 66.851; df = 4; P = 0.000) for this variable, indicating that a majority of teachers believe that the curriculum they have is capable of producing entrepreneurial graduates.

As Part of the Curriculum Offered by The Institution, the Entrepreneurship Programmes Include Practical Elements Aimed at Encouraging the Creation of New Businesses

According to Table 1, 66.7% (agree = 46%; strongly disagree = 20.7%) of the respondents were in agreement with the statement that entrepreneurship programmes include practical elements aimed at encouraging the creation of new businesses as part of the curriculum offered in PILs, 24.1% were neutral and 9.1% disagreed (disagree = 8%; strongly disagree =1.1%). Regarding the entrepreneurship curriculum offered by PILs, the Chi-square test is (x2 = 51.793; df = 4; P = 0.000) in the scoring patterns amongst the respondents. The results differ with various authors who have stated that education in South Africa is designed to produce job-seekers rather than producing job creaters (Santhosha et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurship Education can Alleviate the Fear of Failure in Starting New Businesses

A total of 69% of respondents (strongly agree = 55.2%; agree 13.8%) agreed with the statement that entrepreneurship education can alleviate the fear of failure in starting new businesses, 26.4% were neutral, and 4.6% disagreed (diasgree = 2.3%; strongly disagree = 2.3%). With regard to the statement “entrepreneurship education offered in public inctitutions of learning alleviating the fear of failure”, the Chi-square test is (x2 = 84.552; df = 4; P = 0.000) in the scoring patterns. The results indicate that entrepreneurship education can promote an understanding of business, its purposes, structure and relationship with the rest of society, which is consistent with the findings of Ahmad & Buchanan (2015).

Qualitative Data Analysis

This section focused on teachers’ perceptions of entrepreneurship education and was informed by primary theme which emerged from the thematic analysis, namely:

1. Role of entrepreneurial education.

Theme 1: Role of entrepreneurial education

This theme examines the key concepts of entrepreneurship education and its role is promoting pathways to business start-up while also transforming SA youths into entrepreneurs.

Promoting pathways to business start-up

This subtheme theme looked at how entrepreneurial education promotes a trajectory to business start-up.

Skills and knowledge development

The overriding theme that emerged from the primary data focused mainly on entrepreneurship skills and knowledge development in PILs. This was also a highly ranked sub- theme in relation to promoting pathways to business as it emphasised the skills and knowledge aspect of entrepreneurial education. Such knowledge and skills were identified as the following:

Start and sustain a business

This was a highly ranked factor, whereby skills and knowledge focused on the aspect of how to start and sustain a business. PILs do promote entrepreneurship for students.

Teacher respondent TVET-T3 stated that

We educate our students about the importance of starting your own business. We instil an entrepreneurial mindset in them in order to encourage the importance of self-employment.

Teacher respondent TVET-T7 indicated that in TVET Colleges support business start-ups stating that

It promotes pathways by giving learners skills about starting their business and offer the knowledge needed to start entrepreneurial venture. However, we still have a long way to try and change the perception students have about self-employment. A majority of students still believe in being employed rather than being their own boss.

Teacher respondent UNIV-T1 added that

It encourages them to start small businesses on campus. We do have students who really believe in entrepreneurship and who are innovative, but the issue of space on campus limits their ideas. If we can get business start-up support needs, we could do better if we had more resources and support.

Teacher respondent UOT-T1 stressed that

Entrepreneurship equips students with the relevant skills on how to start and sustain their businesses. In our institution, we promote business start-ups and we encourage students to participate in entrepreneurial activities.

The results are in line with findings by Ismail et al., (2018) who found that entrepreneurship education involves fostering creative skills that can be applied to support innovation. Become a successful entrepreneur requires a set of Technical skills are required to become a successful entrepreneur, but so are opportunities, capabilities and resources. In addition, leadership abilities are required so as to be able to conduct business and teams efficiently. (Bauman & Lucy, 2019) Skills development is perceived by Gordon & Bursuc (2018) as a “strategic management tool to cope with the current business environment mainly because of the market that has changed from one of mass production to one of customisation, whereby quality, price and speed of delivery are emphasised”.

Business Plan

Relating to the above, another highly ranked factor was the skills and knowledge given to students to create their business plans.

Respondent TVET-T3 stated that

We teach them how to draft a business plan. This is a basic aspect of entrepreneurship and it is compulsory for all our first-years.

Respondent TVET-T9 stressed that

The institution teaches learners how to venture into business and develop a business plan.

Respondent UNIV-T6 stated that

We educate our students on how to draw up business plans. The knowledge of a business plan is vital if you are an entrepreneur.

Respondent UNIV-T9 also reflected the importance of the business plan

We make them draft business plans.

The results showed that teachers were positive about the effort they put into entrepreneurship education. At the outset teachers, were confident about their abilities to instil entrepreneurial skills in students. A business plan is a very important strategic tool for entrepreneurs. Gordon & Bursuc (2018) stated that business plan helps entrepreneurs to concentrate on the specific steps necessary to make business ideas flourish, and it also helps to attain both the short-term and long-term business objectives.

Assessment of Whether an Entrepreneurship Education Curriculum Promotes Business Start-Up

The Analysis of Question is presented below

As depicted in the Table 1A & B above, it can be observed that of 83.1% of respondents were in agreement that “An effective entrepreneurship education curriculum allows people to access the relevant knowledge and gain practical skills needed to start an entrepreneurial venture” (strongly agreed 41.9%; agreed 41.2%), 14.0% were neutral, and 2.9% disagreed (disagree= 0.7%; strongly disagree 2.2%). The Chi-square test shown in Table 1A & B was significant at p < 0.05, with a Chi-square value of χ2=112.382 and a degree of freedom of df=4.

| Table 1A Summary of Scoring Patterns | |||||||

| AGREE | NEUTRAL | ||||||

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | |||||

| Count | Row N % | Count | Row N % | Count | RowN % | ||

| Effective entrepreneurship education offers students access to skills and knowledge needed to start an entrepreneurial venture | B1.2 | 32 | 0.368 | 44 | 0.506 | 9 | 0.103 |

| The entrepreneurship education curriculum in the institution is designed to equip students with skills needed to start up their own businesses | B1.3 | 20 | 0.23 | 44 | 0.506 | 18 | 0.207 |

| As part of the curriculum offered by the institution, the entrepreneurship programmes include practical elements aimed at encouraging the creation of new businesses | B1.4 | 18 | 0.207 | 40 | 0.46 | 21 | 0.241 |

| Entrepreneurship education seeks to prepare graduates to be responsible, enterprising individuals who are able to take risks and create new businesses | B1.6 | 23 | 0.264 | 47 | 0.54 | 13 | 0.149 |

| Table 1B Summary of Scoring Patterns | |||||

| DISAGREE | |||||

| Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Chi Square | |||

| Count | Row N % | Count | Row N % | p-value | |

| Effective entrepreneurship education offers students access to skills and knowledge needed to start an entrepreneurial venture | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.023 | 0 |

| The entrepreneurship education curriculum in the institution is designed to equip students with skills needed to start up their own businesses | 4 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.011 | 0 |

| As part of the curriculum offered by the institution, the entrepreneurship programmes include practical elements aimed at encouraging the creation of new businesses | 7 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.011 | 0 |

| Entrepreneurship education seeks to prepare graduates to be responsible, enterprising individuals who are able to take risks and create new businesses | 3 | 0.034 | 1 | 0.011 | 0 |

A total of 86% (40.4% strongly agree; 45.6% agree) of the respondents indicated that “Entrepreneurship education seeks to prepare students to be responsible, enterprising individuals who are able to take risks and create new businesses”, 11.0% were neutral, and 2.9% disagreed. Furthermore, the Chi-square analyses (χ125.176; df= 4) revealed a significant difference at p < 0.05.

Given the previous results, it is interesting to see the results of analysis of the entrepreneurship programmes offered by the PILs involved in this study. A total of 61.8% of respondents agreed (strongly agreed 22.8%; agreed 39.0%) that entrepreneurship programmes offered by the institution have practical elements that are devised to encourage the creation of new businesses, while 24.3% were neutral, and 14% percent disagreed with the statement (disagree= 4.4%; strongly disagree 9.6%). The Chi-square test is significant at p < 0.05, with a Chi-square value of χ2=50.176 and a degree of freedom of df=4.

Qualitative Data

Promoting Pathways to Business Start-up

This was informed by the following:

Skills and knowledge

The highest ranked sub-theme, this was informed by the following in hierarchical order:

Business plan

This was the highest ranked factor whereby business plan writing was a key skill taught to students. Most students highlighted that teachers provided guidance for embedding enterprise and an entrepreneurial mindset. The responses were in line with the findings of Ahmad and Buchanan (2015) which stated that teaching and working methods have been introduced to entrepreneurship education. The most popular teaching methods with final year students in PILs include the creation of business plans followed by class discussion, as well as guest speakers.

Student Respondent Tvt s2 Stated

Teachers assist students with writing the business plan and instilling entrepreneurial behaviour.

Student respondent Tvt s3 notably shared the sentiments of student respondent Tvt s3

By assisting students with writing business plans so they are able to communicate their visions.

Student respondent Tvt s4

By assisting them with writing business plans.

Student respondent Tvt s5

By assisting them with writing business plans in order to help guide their decisions.

Student respondent Tvt s8

The institution provides pathways by helping in writing business plans.

Responses show that teachers in PILs try to develop an entrepreneurial mindset in students through the use of a plan in order to be able to learn how to run a business comprehensively.

Starting a Business

This was the second largest ranked factor and makes logical correlation to the above as business planning was tied to starting a business. Hence, giving the student the knowledge to start a business coupled with skills such as business plan writing is seen as a strong factor.

Student respondent Tvt s10 stated that initiating their own small business helps as they get the idea of what is expected from them in order to grow the business.

It gives us a heads-up on how to start a business and what to expect in the process.

Student respondent Tvt s9 emphasised that

It gives students ideas and ways in which a business can be started.

Student Respondent UNIV-ST5 Highlighted the Important Characteristics of Entrepreneur they Learnt in the Process by Stating That

It provides students with the knowledge to use to start a new venture.

Student Respondent UNIV-ST 7

We are given the knowledge and skills required when starting a business.

Idea-Sharing

Idea-sharing promoted interactivity and stimulated thinking.

Student Respondent UNIV-ST2

We shared ideas about businesses, which helped promote innovation. We connected with other students, which makes the innovations come to life.

Student Respondent UNIV-ST9

They give us the opportunity to come up with our own business ideas and put them into action. We make ourselves open and share with others what we are doing and what our thoughts are.

Experts

Industry experts provided sound advice based on real experience.

Student respondent Tvt s2 mentioned the importance of collaborating with experienced entrepreneurs in facilitating entrepreneurial education:

We get advice from business experts who give clues towards how to control and finance your business.

Student respondent Tvt s4 emphasised the impact of experienced entrepreneurs in entrepreneurship education:

We get advice from successful entrepreneurs.

Limitations of the Study

Due to the way in which the sample was selected (purposive sampling), and the lack of time and/or unwillingness by the respondents to complete the questionnaires, the sample may not be suitably representative. This study focused both on educators and students in PILs in Kwa- Zulu Natal. Five months was allocated to the field work in order to have enough time for distribution, completion and collection of the questionnaires.

Suggestions for Future Research

It is recommended that further research be undertaken in the following areas:

1. This research has generated many questions in need of further investigation. What is now needed is a cross-national, comparative study with a developed country that offers entrepreneurship education. Moreover, South African PILs must improve the integration and inclusion of entrepreneurship education curricula that PILs try to promote.

2. Further research needs to assess the role played by private institutions of learning in contributing to the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education, particularly in KZN.

Conclusion

This study concludes that entrepreneurship education has a positive impact on the performance of small businesses, and it improves the entrepreneurship skills and knowledge of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship education does play a role in the establishment of new business ventures. The study concludes that there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurship education and profitability and business growth. Entrepreneurs not only introduce new goods and services, but also create employment. Public institutions of learning need to incorporate entrepreneurship education into all their curricula in order to raise awareness and challenge student to consider entrepreneurship as a reasonable career path. Strategies to improve entrepreneurship education can create opportunities and help to reduce unemployment and poverty.

References

- Abella, E. (2016). Effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behaviour of secondary students in Rivers State. Master's dissertation, University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

- Akhuemonkhan, I., Raimi, L., & Sofoluwe, A. (2013). Entrepreneurship education and employment stimulation in Nigeria. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences, 3(1), 55-79.

- Akinbami, C.A.O. (2015). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship capacity development from the perspective of a Nigerian university. KCA Journal of Business Management, 7(1), 31-57.

- Asghar, M.Z., Gul, F., Hakkarainen, P.S., & Tasdemir, M.Z. (2019). Validating entrepreneurial intentions questionnaire to assess the impact of entrepreneurship education. Egitim ve Bilim-Education and Science, 44 (197), 383-399.

- Bagheri, A. & Lope Pihie, Z.A. (2013). Role of university entrepreneurship programs in developing students’ entrepreneurial leadership competencies: perspectives from Malaysian Undergraduate students. Journal of Education for Business, 88 (1): 51-61.

- Baldry, K. (2015). Graduate unemployment in South Africa: social inequality reproduced. Journal of Education and Work, 29 (7): 788-812.

- Bauman, A. & Lucy, C. (2019). Enhancing entrepreneurial education: developing competencies for success. International Journal of Management Education: 100293.

- Belitski, M. & Heron, K. (2017). Expanding entrepreneurship education ecosystems. Journal of Management Development, 36 (2): 163-177.

- Bignotti, A. & Le Roux, I. (2016). Unravelling the conundrum of entrepreneurial intentions, entrepreneurship education, and entrepreneurial characteristics. Acta Commercii, 16 (1): 1-10.

- Boi, T. (2018). Pedagogy of communion as promising educational approach for the achievement of global competencies. Journal for Perspectives of Economic Political and Social Integration, 24 (1): 103-123.

- Botha, M. & Bignotti, A. (2017). Exploring moderators in the relationship between cognitive adaptability and entrepreneurial intention: findings from South Africa. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13 (4): 1069-1095.

- Carsrud, A. & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: what do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49 (1): 9-26.

- Cassim, S., Soni, P. & Karodia, A.M. (2014). Entrepreneurship policy in South Africa. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (Oman Chapter), 3 (9): 29-44.

- Chimucheka, T. (2014). Entrepreneurship education in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5 (2): 403-416.

- Cho, Y. & Honorati, M. (2014). Entrepreneurship programs in developing countries: a meta regression analysis. Labour Economics, 28: 110-130.

- Chuanyin, X. & Jin, W. (2014). Entrepreneurship education and venture creation: the role of the social context. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 17: 83-99.

- Claudia, C. (2013). Entrepreneurship curriculum in Romanian universities. Annals of the University of Oradea, Economic Science Series, 22 (1): 1460-1468.

- Criaco, G., Sieger, P., Wennberg, K., Chirico, F., & Minola, T.(2017). Parents’ performance in entrepreneurship as a “double-edged sword” for the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 49 (4): 841-864.

- Eggers, T.D., Herbert, G., George, T.W., Chong, M.F., Lovegrove, J.A., Butler, L., Kennedy, O.B. &, F.T. (2010). Using the theory of planned behaviour to assess if psychosocial determinants of fruit and vegetable intake in a UK adult population change following a dietary intervention. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 69 (OCE6).

- Elmuti, D., Khoury, G. & Omran, O. (2012). Does entrepreneurship education have a role in developing entrepreneurial skills and ventures' effectiveness? Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 15: 83-98.

- Fayolle, A. & Gailly, B. (2008). From craft to science: teaching models and learning processes in entrepreneurship education. Journal of European Industrial Training, 32 (7): 569-593

- Gordon, J. & Bursuc, V. (2018). Law and entrepreneurship education: a proposed model for curriculum development: law and entrepreneurship education. Journal of Legal Studies Education, 35 (1): 123-141.

- Fulgence, K. (2015b). Assessing the status of entrepreneurship education courses in higher learning institutions: the case of Tanzania education schools. Education & Training, 57 (2): 239-258.

- Jabeen, F., Jabeen, F., Faisal, M.N., Faisal, M.N., I. Katsioloudes, M. & I. Katsioloudes, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial mindset and the role of universities as strategic drivers of entrepreneurship: evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24 (1): 136-157

- Jayeoba, F.I. (2015). Entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial abilities. IFE PsychologIA: An International Journal, 23 (1): 219-229.

- Harrington, C. & Maysami, R. (2015). Entrepreneurship education and the role of the regional university. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 18 (2): 29-38.

- Henry, C. & Lewis, K. (2018). A review of entrepreneurship education research. Education + Training, 60 (3): 263-286.

- Hisrich, R.D. & Peters, M.P. (1992). Entrepreneurship: starting, developing, and managing a new enterprise. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Kariv, D., Cisneros, L. & Ibanescu, M. (2019). The role of entrepreneurial education and support in business growth intentions: the case of Canadian entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 31 (5): 433-460.

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., Kew, P. & Monitor, G.E. (2010). Tracking entrepreneurship in South Africa: a GEM perspective.Available:http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.475.278&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Accessed 20 August 2019).

- Ismail, A.B.T., Sawang, S. & Zolin, R. (2018). Entrepreneurship education pedagogy: teacher-student-centred paradox. Education + Training, 60 (2): 168-184.

- Iwu, C.G., Opute, P.A., Nchu, R., Eresia-Eke, C., Tengeh, R.K., Jaiyeoba, O. & Aliyu, O.A. (2019). Entrepreneurship education, curriculum and lecturer-competency as antecedents of student entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Management Education: 100295.

- Lahn, L.C. & Erikson, T. (2016). Entrepreneurship education by design. Education + Training, 58 (7/8): 684-699.

- Littlewood, D. & Holt, D. (2018). Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: exploring the influence of environment. Business & Society, 57 (3): 525-561.

- Maimane, J.R. (2016). The impact of student support services on students enrolled for National Certificate Vocational in Motheo District, Free State, South Africa. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4 (7) 1680-1686.

- Memani, M. & Fields, Z. (2014). Factors influencing the development of productive entrepreneurial behaviour among university students. Journal of Contemporary Management, 11 (1): 287-301.

- Mustapha, M. & Selvaraju, M. (2015). Personal attributes, family influences, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship inclination among university students. Kajian Malaysia: Journal of Malaysian Studies, 33: 155-172.

- Ncube, T.R. (2016). The intrinsic motivational factors of small and medium business growth: a study on the furniture manufacturing sector in the Ethekwini Metropolitan area. Master's dissertation, Durban University of Technology.

- Ncube, T.R. & Zondo, R.W.D. (2018). Influence of self-motivation and intrinsic motivational factors for small and medium business growth: a South African case study. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21 (1): e1-e7.

- Ojeifo, S.A. (2013). Entrepreneurship education in Nigeria: a panacea for youth unemployment. Journal of Education and Practice, 4 (6): 61-67.

- Ondiba, H.A. & Matsui, K. (2019). Social attributes and factors influencing entrepreneurial behaviors among rural women in Kakamega County, Kenya. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9 (1): 1-10.

- Pitso, T. (2019). Invigorating innovation and entrepreneurship: Insights from selected South African and Scandinavian universities. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 11 (1): e1-e9.

- Pruett, M. (2012). Entrepreneurship education: workshops and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Education for Business, 87 (2): 94-101.

- Rahn, D., Schakett, T. & Tomczyk, D. (2015). Building an intellectual property and equity ownership policy for entrepreneurship programs: three different approaches. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 18 (2): 151-168.

- Ramchander, M. (2019). Reconceptualising undergraduate entrepreneurship education at traditional South African universities. Acta Commercii, 19 (2): e1-e9.

- Robb, A. & Valerio, A. (2014). Entrepreneurship Education and Training.

- Sánchez, J.C. (2013). The impact of an entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurial competencies and intention. Journal of Small Business Management, 51 (3): 447-465.

- Santhosha Shetty, G. & Siddiq, A. (2015). Role of undergraduate level entrepreneurship education in self-employment generation and job creation with reference to BHM (Bachelor of Hotel Management) courses in Coastal Karnataka. International Journal, 3 (9): 834-840.

- Schumpeter, J.A. (1951). Essays: on entrepreneurs, innovations, business cycles, and the evolution of capitalism. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Solomon, G.T., Alabduljader, N. & Ramani, R.S. (2019). Knowledge management and social entrepreneurship education: lessons learned from an exploratory two-country study. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23 (10): 1984-2006.

- Spencer, D., Riddle, M. & Knewstubb, B. (2012). Curriculum mapping to embed graduate capabilities. Higher Education Research & Development, 31 (2): 217-231.

- Taatila, V.P. (2010). Learning entrepreneurship in higher education. Education + Training, 52 (1): 48-61.

- Thorgren, S.& Omorede, A. (2018). Passionate leaders in social entrepreneurship: exploring an African context. Business & Society, 57 (3): 481-524.

- Ustav, S. & Venesaar, U. (2018). Bridging metacompetencies and entrepreneurship education. Education + Training, 60 (7/8): 674-695.

- Voda, A.I. & Florea, N. (2019). Impact of personality traits and entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students. SUSTAINABILITY, 11 (4): 1192.

- Waghid, Z. (2019). Examining the business education curricula in South Africa: towards integrating social entrepreneurship. Education + Training,

- Wu, Y.J., Yuan, C.H. & Pan, C.I. (2018). Entrepreneurship education: an experimental study with information and communication technology. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10 (3): 691.