Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 2S

Entrepreneurship Project of the Guambiana Indigenous Community in Colombia: SDG 17 and Entrepreneurship

Cristina Del Prado-Higuera, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

Guillermo Andrés Duque-Silva, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

Elena Bulmer, EAE Business School

Citation Information: Prado-Higuera, C., Duque-Silva, G., & Bulmer, E. (2022). Entrepreneurship project of the guambiana indigenous community in Colombia: SDG 17 and entrepreneurship. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(S2), 1-15.

Abstract

The Misak people have lived in the Indigenous Reservation of Guambía, Department of Cauca in Colombia since time immemorial and have preserved their ancestral identity as well as the habits and customs of their cosmovision. Although their main activity remains agriculture, for some years they have been following an entrepreneurship project with the support of the Yanawai Foundation and with training from a public agency such as SENA to develop a productive and commercial activity for the processing of trout meat and quinoa. This activity is noteworthy for being a generator of employment, innovative in its production process and commercially attractive in the food supply chain. In addition, this project raises awareness within the community of the needs of young people in order to reduce the high percentage of migration of the young to large cities and the cultural shock that this entails. Always present within the development program is the conservation of the harmony of the Misak people and their way of life with their territory with their societal principles of spirituality, nature and economy.

Keywords

Sustainable Development Goals, Colombia, Indigenous Community, Entrepreneurship

Introduction

SDG 17 and Entrepreneurship

The seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were developed at the United Nations (UN) Development Summit at Rio de Janeiro (RIO +20) held in 2012. The main objective of this summit was to create global goals that would resolve global environmental, social, and economic challenges. According to the UN, the definition of Sustainable Development is (to satisfy) the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to satisfy their own needs. This definition of the term “Sustainable Development” is included in the Brunt land report from 1987 that was developed by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), with the aim of developing long-term solutions related to sustainable development and to pursue these goals in the 21st century. Among the topics covered were the role of the international economy, population and human resources, food security, species ecosystems, energy, industry and proposed legal principles for environmental protection (Erling et al., 2014). The new SDGs came into place in 2015. There were 17 goals and 169 targets, and they formed part of the adoption of a document titled Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Gubta & Vegelin, 2016)

The seventeenth SDG (SDG 17), “Partnerships for the Goals”, the aim of which is to, “strengthen the means of the implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development” is an example of a multi-actor type of governance (United Nations, 2021). The idea is that through the development and execution of the different targets comprised within this Goal, and the creation of alliances between different stakeholders, the rest of the SDGs will be achieved. Furthermore, SDG 17, “recognizes multi-stakeholder partnerships as important vehicles for mobilizing and sharing knowledge, expertise, technologies, and financial resources to support the achievement of the sustainable development goals in all countries, particularly developing countries” (United Nations, 2021). In 2019 the 2030 Agenda Accelerator was developed by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) and The Partnering Initiative in collaboration with several other partners to significantly help accelerate effective partnerships in support of the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations and the Partnering Initiative, 2021). A systemic perspective is therefore necessary when developing laws to implement sustainability policies in an effective way. However, it is not only the regulatory authorities that are needed to implement change, but the global effort needed extends to everyone, and thereby exists the need for SDG 17.

Among the elements that the United Nations has identified to be key to address sustainable development challenges is entrepreneurship (Filser et al., 2019). Entrepreneurship is expected to contribute to the three pillars of sustainability, by promoting economic growth, increasing social cohesion, reducing inequalities, supporting climate change mitigation, and putting into place environmentally sustainable practices.

In an SDG context, entrepreneurship needs to also comprise a social or responsible connotation with this being promoted at all societal levels and sectors. Over the past few years, this type of entrepreneurship has been differently described in such terms as “social entrepreneurship”, “ecopreneurship” and “sustainable entrepreneurship” (Filser et al., 2019). Compliance with the SDGs provides entrepreneurs with a realm of different business opportunities, and they are therefore able to reposition their business and redesign their industries in favour of sustainability. Social entrepreneurship for example focuses more on value creation for society rather than primarily on making money. Therefore, it aims to achieve societal objectives. Finally, there is also sustainable entrepreneurship that adopts a comprehensive and holistic approach to societal and environmental challenges, using economic means to achieve desired sustainability objectives.

Entrepreneurship is specifically associated to SDGs 4 and 8 (i.e., listed below with the specific applicable targets). However, there are other SDGs that do not specifically address the concept of entrepreneurship but that may nevertheless offer opportunities and possibilities for entrepreneurs:

• SDG 4: Quality Education – Target 4.4. “By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship”.

• SDG 8: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure – Target 8.3. “Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services”

Although entrepreneurship has been recognized as a driver for promoting sustainable development, there is to date little knowledge as to what extent and under what exact context entrepreneurs can comply simultaneously with the sustainability pillars (i.e., promoting economic growth while progressing on environmental goals and improving social conditions). Therefore, further research is needed in order to motivate entrepreneurs to pursue sustainable challenges (Hall et al., 2010).

This study will analyse the stakeholder landscape of the Misak culture, an ancient indigenous community in Colombia, in order to determine the beneficial impact that entrepreneurial initiatives in the village concerned have had on members of that local community. For the analysis, project stakeholder management tools were used. There are two important reasons for focusing this study on this particular business project. On the one hand, the project is in the Cauca region, in the south-west of Colombia, one of the most excluded and marginalized areas of Latin America due to endemic armed conflict and the absence of state authority. On the other hand, it is an undertaking developed by a vulnerable indigenous ethnic group that has been at risk of disappearing throughout its history. The whole situation therefore presents a very interesting stakeholder panorama.

The Misak Entrepreneurial Project

An Indigenous Sustainable Initiative in the Heart of Armed Conflict

The Misak entrepreneurial project in Colombia is the result of a public-private partnership between the Guambiana community, the National Apprenticeship Service (SENA), the Yanawai Foundation and local governments. The venture's objective is to generate income, contribute to the social development of the Misak community and ensure food sovereignty in the Cauca region through the production of trout and its derived products. The project consists of the ecological production of Golden Trout, as well as the commercialization of frozen and vacuum-packed fish. The cultivated trout is also transformed into hamburgers, nuggets, and meatballs combined with quinoa. This entrepreneurial project also known as “Agroindustriales La Suiza”, has given rise to a successful family and communal business. This initiative has also helped to empower young men and women through training and awareness-raising activities in the community with the aim of reducing the high rate of youth migration to large cities, as well as the potential risk of poverty and social problems (i.e., such as drugs, cultural changes, and problems with the armed forces in the region) that such migration entails.

The Colombian armed conflict has been the longest in the history of Latin America, and has been present for the past 50 years, especially in rural areas. The guerrillas in the country are located in jungle and mountain areas, where the civil population are subjected to very unsafe conditions. The armed conflict in these rural areas has persisted despite several failed attempts over the years to establish productive dialogue between the State and the guerrilla organizations. As a result, Colombia has suffered from an economic recession; the country was close to becoming a failed state, with almost a third of the country being dominated by the guerrillas -mainly the FARC- and another third by the paramilitaries, both groups financed by ever-growing drug trafficking.

In November of 2016, the "Final Agreement for the Termination of the Conflict with the FARC" was signed at the Teatro Colón in Bogotá. The Peace Agreement resulted in the surrender of weapons and the reinstatement of FARC´s ex-combatants into civil society. Furthermore, in rural areas, measures to address the problem of illegal drugs and to promote democracy were also among the matters agreed upon. One of the most positive aspects for the Misak community addressed in the Peace Agreement was comprehensive rural reform. This reform aimed to generate a significant transformation of the rural reality, develop certain regions, eradicate poverty, and promote civil rights among the civil society. The Misak people would benefit from these reforms, as family-run agricultural businesses were proposed to be one of the main keys to promoting peace in the region and developing the rural economy.

However, despite the good intentions embodied in the Peace Agreement between the FARC and the Government of Colombia, most policies proposed around comprehensive rural reform have not yet been implemented. As a result, five years after the agreements were signed, indigenous people from conflict zones such as the Misak in the Colombian south-west continue to live in a state of poverty with no action having been taken to repair the damage from decades of conflict, while still with the risk of new illegal armed groups springing up in the area where they live. The Misak population lives mainly in south-western Colombia. This region has been the most affected in the country by armed conflict over the last six decades. Due to its geography, the south-west of Colombia has been a recurring place for guerrillas, drug cartels, criminal gangs engaging in illegal gold mining, and far-right counter-insurgent paramilitary groups.

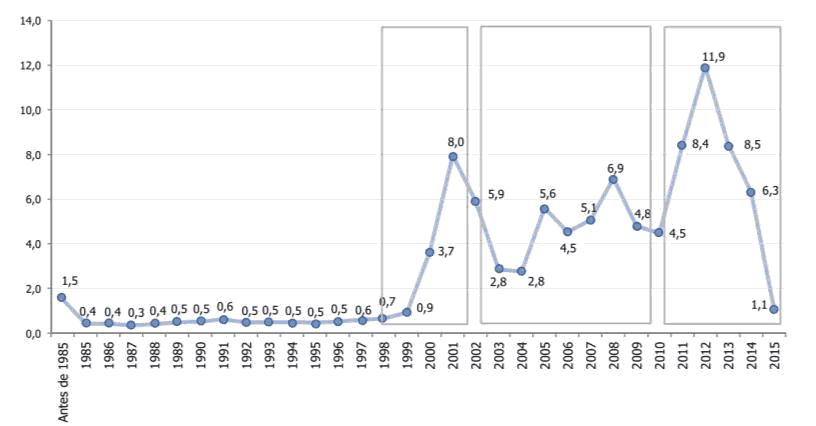

The Guambianos have had to coexist in the middle of the armed conflict for decades. Guerrillas such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), the April 19 Movement (M-19), the Quintín Lame Movement were all present in their territories, as well as the Jaime Bateman Cayón Movement, the Ricardo Franco Frente-Sur Command, the Revolutionary Workers Party (PRT) and the Pedro León Arboleda Command (Ávila, 2009). There is a consensus among historians and researchers of the armed conflict in Colombia, such as Daniel Pecaut (2014), Ariel Ávila (2009), and Álvaro Guzmán Barney (2014), who have pointed out that violence in the department of Cauca, where the Misak people inhabit, has worsened, especially between 1999 and 2005. This period includes the implementation of the so-called “Democratic Security”: the defence policy of the former president of Álvaro Uribe Vélez. Simply between 2002 and 2010, the department of Cauca registered 38,400 civilian victims, 16% of the victims from all over Colombia (i.e., Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total victims per year in the department of cauca 1985 - 2015 in percentages. Based on the official registry of victims with data as of january 1, 2016 (chará, & hernández, 2016, 91)

For some researchers (Caicedo et al., 47), the armed conflict and the militarization of the Cauca territory have allowed the landowners and latifundistas to silence the claims from the indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands. The armed conflict has served as a “smokescreen” to silence the legal and legitimate claim for the return of indigenous lands against the elite of landowners who took them away at the beginning of the 18th century. This permanent struggle for the recognition of indigenous land rights has affected the Misak more directly than the armed conflict itself. Many indigenous people who claim the lands stolen decades or centuries ago are now stigmatized and falsely accused of crimes such as rebellion and terrorism.

Since the 1970s, indigenous communities have tried to organize themselves to defend their rights. During these years, associations such as the Certified Regional Council or the organization of Indigenous Authorities of Colombia representing the communities of the Departments of Cauca, Antioquia, Arauca, Boyacá have emerged. In Casanare, Cundinamarca, Guajira, Meta ... the Misak people (i.e., the target group being studied) have a delegation in the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (“Organización Nacional Indígena de Colombia”).

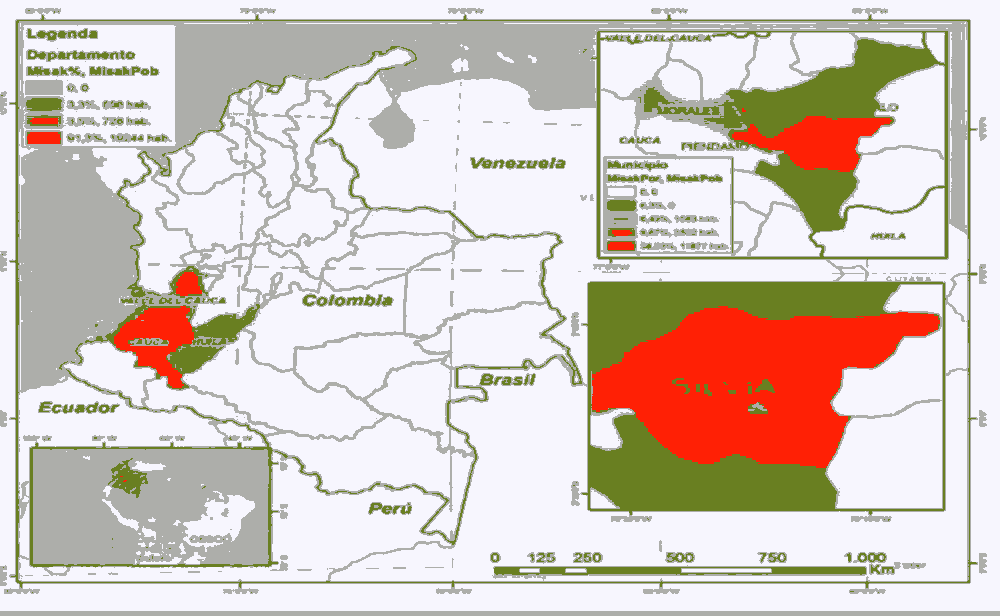

In Colombia, 4.4% of the population is indigenous. This is equivalent to 1,905,617 people. The Misak or “people of the water” represent 1.5% of the indigenous population of Colombia. 79% of the indigenous people live in rural areas and scattered towns (Figure 2). The Misak community is primarily found in the Department of Cauca, where 91.3% of their population lives—followed by the Valle del Cauca Department with 3.5% and Huila with 3.3%. Together, these three departments represent 98% of the Misak territory. Most Misak live in rural areas, with only 8.7% of the population living in urban areas.

The political participation of the Misak community has been very significant since the year 2000 when they obtained political representation at different political levels. For example, in the year 2000, an indigenous leader from the Misak community became governor of Cauca through a popular vote.

Entrepreneurship in the Misak Community

The La Suiza agro industrial project is an example of an entrepreneurship project that entails the development of multiple corporate and non-corporate partnerships in order to attain the project objectives. The company's actions are in line with those to successfully comply with SDG 17.

Young Rural Entrepreneurs MISAK (Agroindustriales la Suiza) is a productive unit that develops agroindustrial activities (i.e., as part of the La Suiza Project), related to the processing and transformation of trout and quinoa meat in the Municipality of Silvia Cauca. It is a company made up of small indigenous family producers dedicated to the production of trout. Since 2015, the Company has formally commercialized some products such as smoked trout and trout meatballs with quinoa, which has allowed it to gain experience in the market.

Objective of the Study

This article will explore the relationship between SDG 17 and the La Suiza entrepreneurial project in Colombia. For the latter, the Misak indigenous community has been ecologically producing golden trout as well as commercializing fresh frozen fish, vacuum packing the latter as well as transforming the fish meat into a number of different products such as hamburgers and nuggets.

Of the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) associated with the 2030 Agenda, in this article we have addressed objective 17, “Partnership for the goals”, which states that "in order for a sustainable development agenda to be effective, partnerships are needed between governments, the private sector and civil society. These inclusive alliances are based on principles and values, a shared vision and common objectives that give priority to people and the planet, and are necessary at the global, regional, and local levels" (Union Nations, 2015). Among its goals is to empower the population and promote public-private partnerships.

This study will analyse the stakeholder panorama of the Misak La Suiza project with the aim of determining the impact that the project´s entrepreneurial initiatives have had in helping societal members. Project stakeholder management tools have been used for this analysis (i.e., these are described in greater detail hereon in the Methods section of this paper).

Methods

The case study analysed was a business project based in the Department of Cauca, Colombia. The objective of this project, carried out by indigenous people of the Misak-Guambiano people, was to produce and commercialize trout under fair and sustainable market principles.

This case study presents a very revealing stakeholder situation, where we see that there are conflicting interests of the Misak people, the regional authorities, and nine external organizations and companies. The stakeholders analysed in this study comprised the following:

1. Yanawai Foundation: The indigenous non-profit foundation in Silvia has been promoting entrepreneurship since its creation. Today it supports the commercialization of trout from the La Suiza company.

2. Mingalerias - Association of Cabildos del Norte del Cauca (ACIN): Organization and Nasa territory, called CXHAB WALA KIWE. It is made up of 22 indigenous councils (traditional indigenous authorities). Of these, sixteen are constituted as indigenous reserves. Thus, it is a point of reference among the indigenous communities of Colombia.

3. Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC): Since 1971, it has been the political structure representing the indigenous peoples of Cauca at the national level. It is an important pressure group for decision-making that concerns the indigenous peoples of Cauca.

4. Agroindustriales La Suiza: Entrepreneurship Company.

5. National Service of Learning (SENA): National public entity that promotes technical and technological education. It supports small businesses with advice, consulting, infrastructure, and seed capital.

6. Universidad del Cauca: Public University in the South of Colombia has 16,500 students. It is the University closest to the area inhabited by the Misak community

7. Universidad del Valle: The most important public University in southwestern Colombia with 32,000 students.

8. Members of the Misak people: Misak community.

9. Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development of the Government of Cauca: The government organ in charge of promoting agriculture and the development of peasants, indigenous people, and Afro-descendants in the Department of Cauca.

10. Business union organization of the sugar industry (Asocaña): Association of large businesses engaged in the production of sugar and sugar-cane derivatives. It groups the central sugar mills in Colombia, whose crops and production plants are primarily found in the Departments of Cauca and Valle del Cauca.

11. Peasant Agroecological Market Network of Valle Del Cauca: Coordination Center of the main peasant markets in southwestern Colombia.

12. Guambía Council: The highest governing authority of the Misak

13. MercaPava Supermarket: Large-scale consumer store that operates in areas of indigenous influence.

14. Food and Agriculture Organization, (FAO): The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. It directs international activities aimed at eradicating hunger and has operations in Cauca. In addition, it has executed projects with indigenous communities in southwestern Colombia.

15. “Olimpica” Superstore: It is a chain of stores distributed in different cities of Colombia. Its owners are the Char, a family of Syrian descent with considerable political influence in Colombia.

16. D1 supermarkets: Low cost, hard discount stores, currently owned by the Koba Group. It has expanded throughout Colombia with 1500 stores. The Santo Domingo family is currently the richest in Colombia.

17. Justo y Bueno (Fair and Good) Supermarket: Owned by Grupo Reve, a company founded in the case of Colombia, by the Chilean businessman Michel Olmi. This low-end store offers products at a low price, constantly renews inventory, and directly targets the most disadvantaged consumers.

18. Other neighbouring Indigenous communities, Nasa Paez: The Nasa indigenous community lives in the Department of Cauca with the Guambianos. The Nasa Paez are located predominantly in the north and west of Cauca. This indigenous community is made up of some 175,978 people.

19. OXFAM, Colombia: The British NGO has been present in Colombia for several decades now. Its primary work in southwestern Colombia is related to poverty eradication and business empowerment projects for indigenous women.

The data on each stakeholder and their participation in the project, as well as their interactions, were obtained through two methods, on the one hand, semi-structured interviews with the manager and members of Agroindustriales La Suiza and on the other hand through observation participants in Guambiano territory, in the municipal capitals of Cauca and Valle del Cauca. The data that we obtained regarding the Guambiano population were compared with the participant observation, and interviews in respect of other projects with rainbow trout carried out by members of the Nasa Paez community. This comparison permits the establishment of reference points on how the different stakeholders contribute to or hinder the development of the Misak La Suiza entrepreneurial project. The contact with the members of the Misak community and the researchers dates back to 2015 in the Celebration of the V Inter-University Summit for Peace in Colombia, held in Cali, Valle del Cauca and continues to the present time.

The stakeholder analyses were based firstly on the development of a stakeholder register (Table 1), which encompassed:

• Stakeholder identification information

• Stakeholder classification information (e., main expectations regarding the project, whether stakeholders were internal/ external to the project, and whether they were supporters, opponents or neutral.

• Problems experienced by interviewed stakeholders.

• Solutions to identified problems.

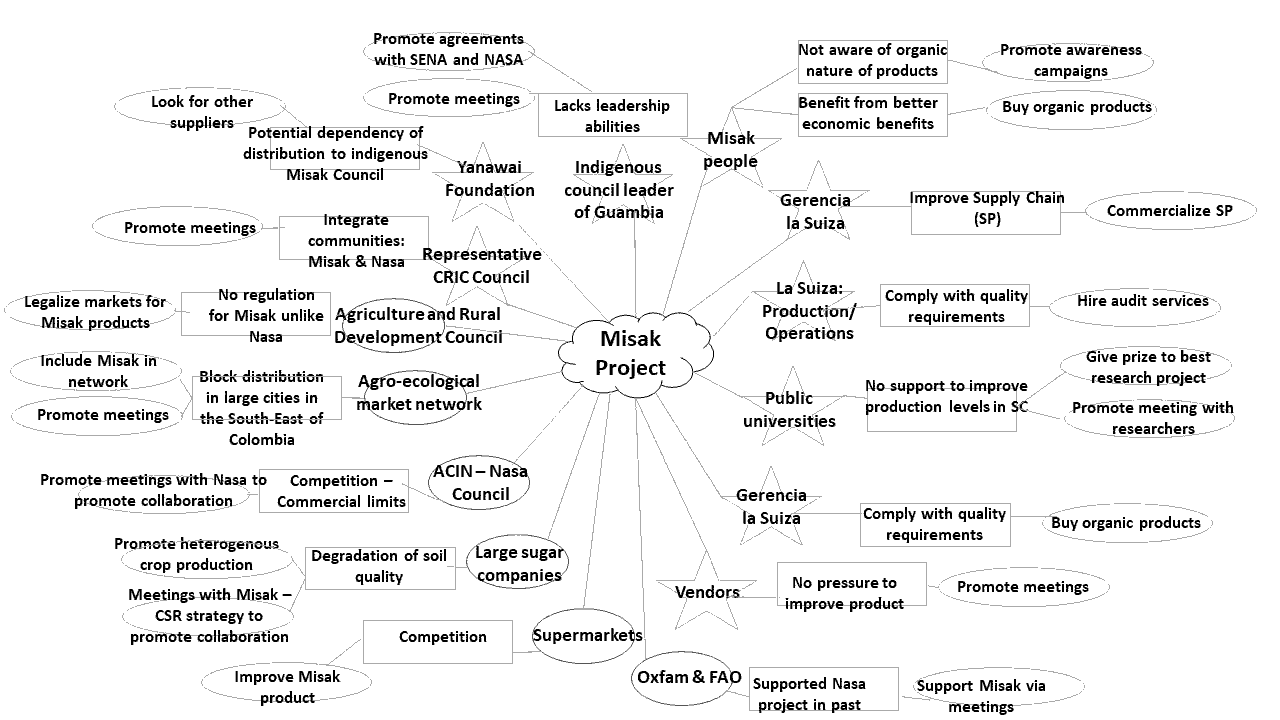

Based on the information included in the stakeholder register, a stakeholder map (Winch & Bonke, 2002) was developed. Using the stakeholder register information, a stakeholder map was conceived to better understand the relationship between the different project actors. For the mapping, Bonk and Winch´s 2002 stakeholder model was used (Figure 1 below). According to this model, the central asset is the project mission, and the identified stakeholders are positioned around it. Their position in the project is identified as being a proponent or opponent as well as the potential problems that may be experienced.

In the results and discussion section, the outcome of the different analyses (i.e., stakeholder register, and stakeholder map) will firstly be presented as well as the general trends that were extracted from the narratives that were developed for this study.

Results

The Misak business project in Colombia is an illustrative example of a complex stakeholder panorama entailing indigenous governing authorities, universities, the entrepreneurial company La Suiza and the Misak communities. For each of the identified actors, their identification details were recorded, along with their main expectations and problems that they may have experienced regarding the project's mission, as well as possible solutions to these problems.

| Table 1 Stakeholder Register of Misak Entrepreneurial Project |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Classification | Problems experienced by these stakeholders | Solutions to these problems | ||||||

| Position | Organization/Company | Location | Role in Project | Main Expectations | Internal/External | Defender/Neutral/Opponent | Problems experienced by these stakeholders | Solutions to these problems |

| Manager | Yanawai Foundation | Silvia, Cauca | Business partner | Commercial management with different indigenous councils (Cabildos) of the Cauca. | External | Defender | Company can diversify to avoid bcoming dependent on a single distributor. | Evaluate the commercial management of Yanawai Foundation and propose improvement and optimization actions between the Project Leader and the Foundation Manager. |

| Consejero Mayor | Mingalerias – Asociación de Cabildos del Norte del Cauca ACIN | Santander de Quilichao, Cauca | Exchange of products, seeds, and knowledge with the MINGAleros of the Nasa-Páez People | External | Opponent | With special participation, Nasa Paez people have generated a union or network of indigenous producers focused on North of Cauca. This has indirectly affected the people who are not part of the network with regard to limitng the product marketing options. | Learning exchanges, meetings with MINGAleros, training courses, and technical assistance to harvest and post-harvest. Establishment of collaborative work among the indigenous peoples of Cauca for the awareness of consumers. | |

| Consejero Mayor | CRIC | Departamento del Cauca y Valle del Cauca | External Project Supporter | Support in the commercialization of local products of the region. | External | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| (Main Council) | ||||||||

| Manager | Agroindustriales La Suiza | Silvia, Cauca | Project Lead | In charge of all project activities. | Internal | No particular problem. | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| Producers | Agroindustriales La Suiza | Silvia, Cauca | Project member | Trout production. | Internal | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| Operators | Agroindustriales La Suiza | Silvia, Cauca | Project member | Internal workforce of production processes. | Internal | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| Family | Agroindustriales La Suiza | Silvia, Cauca | Project management | As a family business, its members are unconditional supporters of the project. | Internal | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| team | ||||||||

| Sena Centro Agropecuario | SENA | Popayán, Cauca | External Project Supporter | Financing with economic resources for the birth of the company, in addition to the different training that the company requires | External | Opponent | Role is limited to with regard to the support they give to the Misak. | Seek support from the SENA Agricultural Center, especially to receive technical infrastructure inputs that allow increasing production in the medium term. |

| Deans | Universidad del Cauca/Universidad del Valle | Popayán, Cauca/ Santander de Quilichao | External consultant and adviser | Technical studies on the linkage to national and international markets of Colombian indigenous companies. | External | Opponent | Lack of technical support. | Agreements with the deans of Administration Sciences to encourage studies and research to design strategiesfairer and more direct marketing and to meet the requirements of suppliers of department stores in Cauca and Huila. |

| Sellers | Miembros del pueblo | Silvia, Cauca | Project member | Minimum purchase of the products. | External | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| Misak | ||||||||

| Coordinator Peasant Markets of Cauca | Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural, Gobernación del Cauca | Popayán, Cauca | External partner unionized | Officialization of peasant and indigenous markets in the 42 municipalities of the Department of Cauca guarantees the continuity of the fair and direct marketing of the company's products. | External | Opponent | Difficulties in institutionalizing agroecological peasant markets and peasant and indigenous business rounds through Ordinances of the Departmental Assembly of Cauca. | Through the Governor of the Guambia Council, file a proposal for an Ordinance in the Cauca Departmental Assembly to institutionalize new peasant agroecological markets and peasant and indigenous business meetings. These should be held on a frequent basis. |

| Manager | Asocaña | Cali, Valle del Cauca | Industrial guild | Work and get support from Asocaña to support small scale production as part of the CSR strategy in the region. | External | Opponent | Promotes sugar cane monocultures amongst peasant and indigenous territories. | Mitigate the monoculture's perverse effects. Through social seed-exchange programs of exchanging and ancestral agroecological knowledge in Cauca to promote greater social recognition of the indigenous and peasant economy both at the local and national levels. |

| Coordinating Board | Red de Mercado Agroecológicos campesinos del Valle del Cauca. | Tuluá, Valle del Cauca | External distributor | Participate in the seven agroecological markets of the Network with Arcoris Trout, hamburgers, nuggets, sausages, and meatballs of Trout with Quinoa, expanding the presence Agroinstriales La Suiza in Valle del Cauca. | External | Opponent | La Suiza currently is unable to participate in the agroecological markets of the network. | Meetings with the Network Coordinating Board to exchange knowledge to negotiate La Suiza´s presence in the markets. |

| Governor | Cabildo de Guambía | Guambía, Cauca | Project Supporter | Minimal business management | External | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| Producers external | Miembros del pueblo Misak | Silvia, Cauca | Project member | Expect to be producers of raw materials and supplies for the needs of the company. | External | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| Manager | MercaPava | Puerto Tejada, Cauca | Trading Store | Add new rainbow trout derived products in company's products portafolio. | External | Opponent | Sell La Suiza´s procucts in supermarket premises. | Facilitate and support market access for Misak indigenous family economy producers through dialogue and meetings. |

| FAO Delegate in Colombia | FAO | Bogotá | UN body External Cooperation | Expand to the Misak People the type of support provided to the indigenous Nasa between 2017 and 2019 in the municipality of Caldono, with the cooperation of the Territory Renewal Agency, to strengthen local business development organizations. | External | Opponent | The organization does not presently support the Misak. | Promote meetings with FAO to strengthen the socio-business and commercial capacities of organizations by providing technical assistance for linking to regional markets. |

| Manager | Supertienda Olimpica | Popayán, Cauca | Trading Store | The commercialization of indigenous agroecological products in the "Bio" line of these department stores | External | Opponent | Supermarket does not sell Misak products. | Promote meetings with Olimpica so ensure that Misak products fulfil stds required by the store. |

| Regional administrator | Tiendas D1/ Justo y Bueno Popayán | Popayán, Cauca | Trading Store | The commercialization of indigenous agroecological products retail and at low-cost stores. | External | Opponent | Supermarket does not sell Misak products. | Promote meetings with Olimpica so ensure that Misak products fulfil stds required by the store. |

| Governors | Otras comunidades Indígenas | Departamento del Cauca | Business partner | Purchase products in agreement with state institutions (Colombian Institute of Family Welfare I.C.B.F and food programs school P.A.E. | External | Defender | No particular problem. | Solution not required |

| Director | OXFAM, Colombia | Bogotá | ONG External Cooperation | Institutional support and training to access local and regional markets in fair conditions. | External | Defender | The organization does not presently support the Misak, only the Nasa. | Promote meetings with Oxfam Colombia to strengthen the socio-business and commercial capacities of organizations by providing technical assistance for linking to regional markets. |

The stakeholders listed in Table 1 were also categorized as being internal or external to the project, as well as whether they supported or opposed the project. Furthermore, the information compiled in the stakeholder register was further analysed via the development of a stakeholder map for the project, whereas shown below in Figure 1, project supporters were characterised by stars and project opponents by hexagons. Although the trends extracted from the stakeholder map are further described in the Discussion section below, it is possible to observe that most of the interviewed stakeholder groups supported the project mission.

The project has twenty-one stakeholders, of which nine oppose the La Suiza entrepreneurial project. Most of the latter were stakeholders that were external to the project venture. The Nasa indigenous community is one of these, and they are competitors as they hinder the Misak´s access to potential distribution and sale channels. A further opponent are the stakeholders that have a significant presence in the region such as sugar mil unions, as they compete for land and promote cane sugar monoculture production (i.e., which is unsustainable). Finally, western supermarkets also suppose a barrier to the geographical distribution of indigenous products to large consumer areas as they are currently not sold in the latter.

Through our study it was found that those stakeholders that defended the project had some connection to the Misak indigenous social structure. For example, family members of the La Suiza company were also members of the Misak indigenous community. Below we can observe the stakeholder map of the La Suiza entrepreneurial project.

The perspectives of the different stakeholder groups interviewed were compiled so that trends could be extrapolated. Some of the trends observed indicate a risk of entrepreneurship stagnation for four main reasons:

1. The company depends on a few stakeholders who help in the commercial distribution of the products.

2. Technical support in infrastructure and marketing is needed to bring trout products to stores in the regional market.

3. The region's universities must offer specialized training and consulting in process improvement. The support of universities will be essential to ensure the economic sustainability of the organization (i.e., and organization that is based on expertise and scientific knowledge) (Alcoba-Malaspina, 2019)

4. There is evidence of a need for training and consulting in leadership that would allow the Misak authorities to promote and establish effective alliances with the stakeholders who oppose the project.

Discussion

In recent years the Colombian economy has experienced a significant boom thanks to the climate of legal security, fiscal incentives, good macroeconomic management, and a significant inflow of foreign capital that has led to high growth rates, with low inflation and little debt.,

Over the last few years, the international community has been supporting the Colombian economy. To date Spain has been the largest foreign investor followed by the US, Mexico, Panama, and United Kingdom. Although investment from abroad has helped to transform and modernize many sectors in Colombia, 28% of its population still has a very low purchasing power and live-in poverty. Marginalization and inequality also permanently affect the indigenous population and other ethnic groups, despite the fact that the 1991 Constitution in its seventh article states that the "Colombian State recognizes and protects the ethnic and cultural diversity of the Colombian Nation", it is not coincidental that four of the five departments with the highest poverty rates are also departments with indigenous or Afro-descendant populations, among them: Chocó (68% of poverty, where 100% of the population is composed of Afro-Colombians and indigenous people); Cauca (62.1% of poverty with 44% of indigenous and Afro-Colombian); Córdoba (60.2% of poverty and almost 25% of Afro-Colombian and indigenous population); La Guajira (58.4% of poverty, with 44% of indigenous people and 14% of Afro-Colombians) and Magdalena (52.3% of poverty) (Minority Rights, 2008)

Therefore, international support and private public alliances are fundamental for these communities that have suffered the consequences of the long-armed conflict. Some of these groups, especially indigenous groups, have had to rely on different entrepreneurial activities which include the making of handicrafts and ecotourism to ensure their sustainability as well as the development of agricultural companies.

Some of these new production models would not have been possible without the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals. A historic opportunity has been provided for Latin America and the Caribbean since the General Assembly of the United Nations established a transformative vision of economic, social and environmental sustainability of the 193 Member States that subscribed to it. The SDG also served as a road map for some of the Colombian institutions that address priority issues of the utmost concern such as reducing inequality, inclusive economic growth with decent work for all, sustainable cities and climate change ...The creation of alliances and the development of entrepreneurial initiatives are not new endeavours for the Misak Community in Colombia. In Colombian indigenous communities, the theme of the association or grouping for the promotion of productive activities has been present since pre-Hispanic times. Earliest reports tell of the family union or alliance of individuals to manage forms of production and coexistence in populations of the Caribbean region and the Colombian Andean region. Initially, the associative forms were generated for the implementation of works such as: planting and harvesting of crops, lifting and adaptation of community housing, opening trails or roads for displacement. A key feature was the ease of interacting and integrating to achieve common objectives (Pitre-Redondo et al., 2017).

The Misak entrepreneurial project is an example of an illustrative stakeholder panorama where it is possible to observe how the Misak tribe is limited regarding the potential success of their project due to limited market accessibility and international aid. One of the big problems is the existing rivalry between the Misak and the Nasa Paez Community that cohabit the same geographical area. The Misak would be potentially able to better compete (i.e., grow organically) with regard to their value chain through mergers and strategic alliances, which at the moment is not the case (Planellas & Parada, 2006).

The La Suiza agro industrial project is a clear example of an entrepreneurship project that entails the development of multiple partnerships to attain the project objectives, which is very much aligned with the successful execution of SDG 17. The entrepreneurial projects aim primarily at processing and transforming trout and quinoa meat. A clear example of the creation of alliances is how the company associates small producers which mainly entail indigenous families with market opportunities in the municipalities of Silvia, Piendamó, Popayán in the last three years as well as some municipalities of Valle del Cauca. The company is currently being recognized as an employment generator. Furthermore, the company´s objective with respect to the carrying out of these projects is also to generate income and food sovereignty, contributing therefore to the social and economic development of the region.

A problem that the Agroindustriales La Suiza company has encountered over time with regard to a number of stakeholders such as from OXFAM and FAO, is the lack of technical advice, notably knowledge support as to how to increase market share and create better distribution channels (i.e., fair trade if possible). In this sense, it is necessary to establish strategic alliances between the representatives of Agroindustriales La Suiza, the authorities of the Cabildo de Guambía, and the deans of the local universities, Universidad del Valle and Universidad del Cauca, to provide the company with the necessary technical support to be able to improve and make more efficient the company´s production and distribution processes.

There is no doubt that the experience of the Nasa Paez community with NGOs such as OXFAM and FAO can serve as a model for the Guambian Misak community. In general, a dialogue is necessary with the trout producers of the Nasa ethnic group to exchange knowledge, production techniques, organization, and, particularly, experiences of international cooperation. Furthermore, we believe that a product quality improvement path similar to the one carried out in the Nasa Paez communities with the support of OXFAM and FAO could help the Misak community meet the technical quality requirements needed to bring their products into supermarkets.

Similarly, the stakeholder analysis indicates that it is necessary to re-establish a dialogue with SENA in order to receive technical support in terms of infrastructure, significantly improving the product's presentation and reducing its production costs.

All these alliances and the increase in public advocacy in the Cauca government and the municipalities of Popayán, Silvia, Piendamó, and Morales require better leadership from the Guambian council authorities. In this sense, as a transversal axis to the recommended actions, it is necessary to strengthen the leadership of the community members, perhaps through a consultancy.

One of the objectives of the La Suiza entrepreneurial project is rural development, a strategy designed to improve the economic and social life of indigenous communities. For this the commitment of public administrations is essential to incentivize these entrepreneurship programs, helping them to strengthen commercialization, improve production with new processing plants and encourage new skills such as the ability to solve problems, analyze, plan, evaluate and make decisions. As stated in objective 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals "a successful sustainable development program requires partnerships between governments, the private sector and civil society", which is why the Yanawai Foundation has for several years been working to combine efforts and build a harmonious space between the Misak people and nature, seeking a more just, sustainable, and healthy society.

Conclusion

The seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were developed at the United Nations (UN) Development Summit at Rio de Janeiro (RIO +20) to resolve global environmental, social, and economic challenges. Among these main sustainable development challenges to address is entrepreneurship, which is expected to contribute to the three pillars of sustainability; promoting economic growth, helping to mitigate climate change and implementing environmentally sustainable practices. Although entrepreneurship has been noted as an important driver of sustainable development, there is to date little knowledge as to what extent entrepreneurs can comply simultaneously with the sustainability pillars

The La Suiza agroindustrial project is a clear example of an entrepreneurship project that entails the development of multiple partnerships in order to attain the project objectives, which is very much aligned with the successful execution of SDG 17. Although the Misak case study is a wonderful entrepreneurial endeavour, it has its limitations and some of these are a result of the different relationships that surround the project, such as the rivalry between the Misak and the Nasa Paez that cohabit the same geographical area. A further problem is the lack of technical advice and knowledge from specific stakeholders such as the universities and the Sena. In this sense, it is necessary to establish strategic alliances between the representatives of Agroindustriales La Suiza, the authorities of the Cabildo de Guambía, and the deans of the univerities Universidad del Valle and Universidad del Cauca, to provide the company with the necessary technical support to be able to improve and make more efficient the company´s production and distribution processes.

We can conclude from this study that the project La Suiza is generating multiple benefits for the Misak indigenous community with respect to food security. The analyses of stakeholder relationships however seem to indicate that new alliances will be a way forward to ensure the future of the endeavour.

We also noted that the Misak community at the entrepreneurial level, needs the technical support from entities such as SENA, OXFAM, and FAO at the infrastructure and marketing levels. The authors of this text recommend that there be a closer association with universities of the region, especially the Universidad del Cauca and the Universidad del Valle, to organize more specialized training and consulting to improve the production and distribution processes.

The armed conflict has badly hit the region of Colombia inhabited by the Misak. It is for this reason that some difficulties were encountered when identifying stakeholders that were of an illegal nature. We therefore consider that future research should be carried out on the role of insecurity generated by criminal organizations such as the "BACRIM," the Aguilas Negras, and "Los Rastrojos." Research on these stakeholders will help to better understand the contextual landscape and challenges that indigenous enterprises such as Agroindustriales La Suiza face.

References

Agredo, O., & Marulanda, S. (1998). "Guambiano life and thought". Indigenous Council of the Guambia Reservation. Guambía, Cauca.

AICO (Indigenous Authorities of Colombia). (2019). Viewed web: www.aicocolombia.org http://www.cric-colombia.

Alcoba-Malaspina, O. (2019). Innovative business ecosystems. Harvard Deusto Business Review, 289, 34-44.

Arango., & Sánchez. (2004). The indigenous peoples of Colombia on the threshold of the new millennium. Bogotá: National Planning Department.

Ávila, A. (2009). Armed conflict in Cauca Colombia: Reconfiguration of the regional power of the armed actors. Bogotá: New Rainbow Corporation.

Guambía Council. (2007). "K Misak Ley, for the defense of the greater right, heritage of the Misak people." Guambia Council, Ancestral Authority of the Misak People. Silvia, Cauca.

Caicedo-Domínguez., Y., Hoyos-Garcés., G., Yépez., R., & Sandoval-Pinedo., D. (2021). “Agroindustrial uses of the coca leaf in indigenous communities of the department of Cauca, Colombia during the post-conflict”. Political Journal Globality and Citizenship, 7(14), 44-62.

Navarrete, C. (1994). Guambian textile objects. University of the Andes. IADAP (Andean Institute of Popular Arts of the Andrés Bello Agreement). Editorial IADAP. Quito, Ecuador.

Chará, W., & Hernández, V. (2016). "The victims of the internal armed conflict in the department of Cauca 1985-2015". Magazine Via Iuris, 85-107.

CRIC (Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca). (2019). Viewed institutional web: http://www.cric-colombia.org.

CRIC. (2009). Land presentation document on the defense of the territory. Cited in: Network for Life and Human Rights of Cauca. "Biannual report on the situation of Human Rights in Cauca years 2005 and 2006".

Flórez-Vargas, C.A. (2016). "The concept of major law: An approach from cosmology". Dixi, 63-74.

Barney, Á., & Pizarro, A.N. (2014). "Reconfiguration of local orders and armed conflict: The case of three municipalities in Norte del Cauca (1990-2010)". Society and Economy, 155-184.

Public Institution of Technical and Scientific Support to the National Environmental System. (2015). National Water Study: Information for decision-making.

Medina Cruz, I.R. (n.d.). “Strategic Planning, a pillar in business management. Pacioli's mailbox ”.

Minority Rights Group International. (2008). “World directory of minorities and indigenous peoples - Colombia: Afro-Colombians”.

Observatory of the Presidential DH and IHL Program. (2009). "Diagnosis of the situation of the indigenous coreguaje people."

ONIC, National Indigenous Organization of Colombia. (2021). Viewed institutional web: www.onic.org.co.

Pachón, X. (2000). "The Wampi or the Guambía people." In: ICCH. Human Geography of Colombia, 2 & 4. Bogotá: Luis Ángel Arango Library.

Pécaut, D. (2014). An armed conflict at the service of the social and political status quo. In Contribution to the understanding of the armed conflict in Colombia. Bogotá: Historical Commission of the Conflict and its Victims.

Phillips, V. (n.d.). "Basic manual for the farming of rainbow trout". Recovered from: https://issuu.com/lcamues/docs/manual-basico-para-el-cultivo-de-trucha-arcoiris

Pitre-Redondo, R., Cardona-Arbeláez, D., & Hernández-Palma, H. (2017). “Projection of indigenous entrepreneurship as a mechanism of competitiveness in the Colombian post-conflict”. Research, Development and Innovation Magazine, 7 (2), 231-240.

Parada, P., & Planellas-Aran, M. (2007). What is a corporate strategy? Harvard Deusto Business Review, 153, 34-51.

Misak, P. (2005). "Mandate of Life and permanence Misak Misak". Ancestral authorities of the Nam Misak people. Piendamó, Cauca: Guambia Council.

Rangel, A. (2008). "Prospects for peace and security." Criminality, 50(1), 417-432.

Torrijos, V. (2014). Cartography of the conflict: Interpretative guidelines on the evolution of the Colombian irregular conflict. In contribution to the understanding of the armed conflict in Colombia. Bogotá: Historical Commission of the Conflict and its Victims.

United Nations. (2015). Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 25 September 2015.

Received: 06-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. jleri-21-8871; Editor assigned: 08-Dec-2021, PreQC No. jleri-21-8871 (PQ); Reviewed: 19-Dec-2021, QC No. jleri-21-8871; Revised: 30-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. jleri-21-8871 (R); Published: 06-Jan-2022