Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 1

Entrepreneurship Education: The Case of the ABA Master at the University of Studies of Parma

Francesca Cavallini, Social Cooperative Tice Onlus

Adele Carpitelli, Social Cooperative Allenamente

Paola Corsano, University of Studies of Parma

Traci M. Cihon, University of North Texas

Abstract

The International Labour Organization (ILO) shows that in the last ten years we are witnessing a weakening of the global economy, with a consequent decrease in employment rates. The scientific research has focused on the theme of entrepreneurship education as an instrument in response to the crisis. In this paper the impact of University Master Courses has been analyzed, in addition to specific content, it proposes an integrated path of entrepreneurship education in the social field through focus group activities, specific consultations with the entrepreneur and an intense period of project work in the company. The effects on employment of the first four editions of the Master are analyzed: the employment status of the 77 students at the time of enrollment, at one year after its conclusion, at two years after its conclusion and in 2017.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship Education, Third Sector, Social Enterprises.

Introduction

In 2007, the outbreak of the global economic crisis, still persistent in its effects, had a great impact on the employment sector. International reports show its consequences on the economic and labour market on a yearly basis. The 2016 International Labour Organization report on employment trends (ILO, 2015:2016) confirms the decline of the global economy and the increase of the unemployment rates, although less steeply then what was predicted. Another ILO study focuses on the condition of youth employment: the Global Employment Trends for Youth 2015 records an unemployment rate of around 13% among the young population (against a pre-crisis rate of 11.7%), estimating a total of unemployed people aged below 25 years of around 73.3 million (ILO, 2015). The report also points out how young women and men who are now more educated than in the past, face more difficulties in the labour market.

Main Italian, European and global institutions managing and coordinating the development of the educational processes have been working through these years to understand which variables are more related to the entrepreneurship education (Caggiano, 2015; Caggiano, 2016). In particular, the European Union establishes entrepreneurship as one of its 8 key competences, considering it as one of the fundamental elements to tackle unemployment and to face the economic challenges due to the worldwide crisis. The Global Entrepreneurship Education (GEE) of the World Economic Forum (WEF) also recognizes entrepreneurship education as a crucial element needed in order to achieve a sustainable social and economic development. In its document EntreComp (Bacigalupo et al., 2016): The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (European Commission, 2016) the EU declares its commitment to elaborate a common theoretical and epistemological approach to promote entrepreneurship and to open a real dialogue of exchange between the education and the labour sectors.

National and international literature also looks at the entrepreneurship education issue as one of the key answers to the global crisis (Volkmann, 2009). Over the past twenty years, the number of courses and programmes dedicated to entrepreneurship education has significantly increased (Katz, 2003; Kuratko, 2005; Nabi et al., 2016). Meanwhile, entrepreneurship education has become a subject of the scientific research (Fayolle, 2007; Fayolle et al., 2006; Fayolle & Kyrö, 2008; Neck & Greene, 2011; Pittaway & Cope, 2007a). The studies primarily addressed the different pedagogical and psychological theories investigating the phenomenon of entrepreneurship education (Pittaway & Cope, 2007a), and how these approaches influence the students’ propensity to undertake a business activity (Bae et al., 2014). However, many authors sustain the necessity to deeper analyze the existing research corpus, particularly with regards to the different methodologies adopted (Fayolle et al., 2016; Pittaway & Cope, 2007a), the mainstream approaches (Pittaway & Cope, 2007b), the students’ motivation (Kassean et al., 2015), the individual differences (Corbett, 2007; Politis & Gabrielsson, 2015) and the strategies used to teach the specific competences of an entrepreneur (Lackeus, 2015). With respect to the teaching strategies, in terms of different competences, numerous authors affirm the importance and the necessity of the experiential education approach–known as learning by doing (Gorman et al., 1997; Laukkanen, 2000; Gibb, 2002; Sogunro, 2004; Heinonen & Poikkijoki, 2006; Rasmussen & Sørheim, 2006). Any author approaching the study of entrepreneurship education needs to recognize the normative local framework (Welter, 2011; Welter et al., 2016) and the role played by national institutions in facilitating the business start-up phase (Walter & Block, 2016), because that becomes a key predictor of the “entrepreneurship education” success (Refai & Klapper, 2016; Urban & Kujinga, 2017).

Both secondary and higher education in Italy seem to have interpreted the European institution’s message on entrepreneurship education quite superficially, by reducing it to a specific core of subjects in university courses or to secondary schools projects. Except for higher education courses such as Economics, Management, and Industrial Engineering, along with Business and Administration Master courses (MBA), our country appears to totally lack specific initiatives and centralized guidelines in favour of the promotion and diffusion of entrepreneurship education (Caggiano, 2016). Italy appears to be working slowly on this matter, especially with regards to the higher education sector. The uncertainty around the meaning of entrepreneurship education, the complexity in training academics and professors on the subject, the difficulties in involving professional entrepreneurs in training and educational courses and the traditional academic evaluation system (rating knowledge rather than competences and behaviours) are just some of the actual impediments undermining the spread of entrepreneurship education (Piazza, 2015). Another interesting research issue which relates to entrepreneurship education is the evaluation of the “external” education efficacy, in terms of employability of people enrolled in a course of study. Fondazione CRUI (2003) considers this issue at the utmost importance for the academic and post-academic evaluation. “External” efficacy is considered as the efficacy measured on the field, and not merely as a function of the didactics–as currently evaluated for Italian students at university. Moreover, the indicators considered for external training efficacy are objective and related to the level and the rapidity of employment for graduates, professional upgrading for new employees and increases in professional opportunities for those already working, along with other subjective parameters, like the level of satisfaction for the training received. Researcher suggests, in accordance with a common orientation, that competitiveness and sense of entrepreneurship are replacing the search for a steady job in young graduates. This represents a clear turnaround even with respect to the recent past, back when the graduate, mostly female, tended to turn to the public sector for employment, because its structures offered a steady position, a certain degree of working autonomy and self-paced deadlines. Today the average graduate largely addresses the private sector rather than the public one. The so called “private social work” (or third sector) and the school institutions are limited to a restricted number of people, mainly females, with a “vocation”. The rapidity and number of new employments are the main indicators of the efficacy of the didactics.

The external efficacy of the employment sector is expressed according to the following indicators: the percentage of new graduates who find a job within one year, the percentage of new-graduates who are still looking for a job after few months; as far as it concerns the self-employment condition, the expected dimensions might consider instead the possibility to take over a pre-existing activity or the launch of a new business, as well as the percentage of graduates entering the labour market after graduation. This “propensity to outplacement inside the labour market” is a measure of the guarantee that the new academic title can offer to people already employed who are searching for other job opportunities, more in line with their expectations. Sometimes, workers who change jobs tend to start from an inferior level, obviously where they see higher economic, social and professional perspectives. This indicator is then a measure of the guarantee given by the academic title.

To verify the impact of higher entrepreneur education on the development of students’ employment, is important to consider the entrepreneurial profile. The entrepreneurial profile is supported by both entrepreneurial characteristics and entrepreneurial intention that, in turn are supported by entrepreneurial education and skills (Centobelli et al., 2016). The contributions of entrepreneurial characteristics have been studied in several studies and in different countries and open mindedness, the need for achievement, pragmatism, tolerance of ambiguity, being visionary, taking challenges, risk taking, and the internal locus of control are some dimensions of personality traits which lead a person to develop the entrepreneurial intention. Even though the literature on entrepreneurial and skills should be improved, it is possible to summarize the different dimensions of the specific skills required to train a future entrepreneur. Centobelli et al. (2016) identify and define six dimensions connected with entrepreneurial skills:

1. Personal skills.

2. Innovative skills.

3. Financial skills.

4. Organizational skills.

5. Strategic skills.

6. Relational skills.

The identified skills, further supported through empirical research, will prove instrumental in the training of entrepreneurs, offering a measurement tool to assess skills in future entrepreneurship skills research.

This paper presents a case study on the impact analysis of a University Master Course, which includes, besides specific content, an integrated course on social entrepreneurship education. The Master Course is realized in collaboration with a local non-for profit company, and promotes the educational subject through internal focus group activities, specialized consultancies with the entrepreneur and an intense period of project work inside the company. The study analyses the effects on occupation within the first four editions of the Master Course. The employment status of 77 students was detected at the moment of enrollment in the course of study, after one year, after two years and again in October 2017. The authors intended to verify whether from the beginning of the course of study, within 1, 2 or more than 2 years after its conclusion, the number of students engaging in a business activity has increased or not, and which factors or characteristics related to the Master Course might have fostered this increase.

The Master Course

A university Master course promotes specific knowledge and competences in a certain field or in a professional activity. The level of the Master might vary according to the national legislation, and various levels might co-exist in a Country system.

The 1st Level of University Masters in Italy is included in the second cycle of the higher education, as defined by the “Processo di Bologna” (Bologna Process) regulation. A 1st Level Master typically includes 90-120 ECTS credits (60 ECTS is the minimum required for a Master course). A 1st Level Master is corresponding to the seventh level of the European Qualification Framework (Laurea Magistrale, Diploma Accademico di secondo livello, Master universitario di primo livello, Diploma Accademico di specializzazione primo, Diploma di perfezionamento o Master primo), while a 2nd Level Master corresponds to the eighth European level (Dottorato di ricerca, Diploma accademico di formazione alla ricerca, Diploma di specializzazione, Master universitario di second livello, Diploma Accademico di specializzazione secondo, Diploma di perfezionamento or Master secondo).

Only in Italy is a Master considered as a post–secondary academic degree, given that in all Europe it refers to a second cycle academic degree. Unlike Laurea Magistrale (two-year course of specialization after graduation), the 1st Level Master does not grant access to third cycle courses such as Dottorato di ricerca (PhD), because it is not included in the national didactic system and its title is granted under the responsibility of the single university institute.

One can access a 1st Level Master after obtaining a Laurea (Bachelor degree) or an equivalent and legally recognized title, while the 2nd Level Master is reserved to those who obtained a Laurea Magistrale degree or Laurea Magistrale ciclo unico degree (five/six year course of specialization).

A university Master might then have a clear, legal identity, but its attainment does not directly imply recognition from private companies and enterprises, even with an appropriate promotion campaign. However, some education institutions might occasionally have contacts with enterprises that contribute to finance the course of study. In this case students may have the opportunity to do an internship aimed at a future job placement. University Master courses usually last one academic year and requires the achievement of at least 60 academic credits. The duration of a Master course is subject to different interpretation: some universities activated Master courses longer than 1 year but shorter than 2 years (e.g. 14 months duration), while other academic courses (Laurea, Laurea Magistrale, Specializzazione, Dottorato di ricerca) have necessarily been organized by academic years. Masters are promoted by universities, most of the time in collaboration with external training centres and private companies, and they are not necessarily held inside the university; rather, they are held departments, institutes, specialized schools or other centres. These are not permanent structures, therefore the course of study might not be re-confirmed the following academic year.

The Aba Master

The Master Course in Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), held by the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences of Parma University, was instituted in the academic year 2011-12, being for the following four years the only academic Master dealing with applied behaviour analysis.

ABA, as a science and as an educational offer, it has been examined for more than five years by students and professors working in the socio-educational sector. Different Master courses in Italy address the topic (e.g. http://www.iescum.org/doceboCms/).

Since 2011, after the publication by the Istituto Superiore di Sanità of Linee Guida 21 (guidelines 21), which identify the efficacy of the various models derived from applied behaviour science in the treatment of children with autism, other Italian universities developed similar educational offers (e.g. University Kore, city of Enna; University of Salerno). In particular, Linee Guida 21 endorses the evidence of ABA efficacy in enhancing the Intellectual Abilities (IQ), the language and the adaptive behaviours in children with autistic spectrum disorders. The availability of evidence, even though not conclusive, allows the recommendation of the use of ABA in the treatment of individuals with autism spectrum disorders.

ABA represents the systematic application of behavioural principles identified by the science which studies the behaviour and its regulatory laws. It also intends to be a scientific approach for practical techniques of project definition, implementation and evaluation of intervention programmes (Perini, 1996).

The Master Course in Applied Behaviour Analysis of the Department of Humanities, Social Sciences and Cultural Industries of the Parma University of Studies was introduced for the first time in the academic year 2011-12 as a second-level Master, proposed and activated again in the academic years 2012-13 as a first-level Master, in 2013-14 again as a second-level Master, and in 2014-15 as a first-level Master. Finally, in 2016-17 two editions were activated, one first-level course and one second-level course.

Hereinafter the first four editions (2011-12, 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15) are analyzed. They maintained an unvaried curriculum, selection modalities, professors and project work. The first-level editions of academic years 2012-13 and 2014-15 have introduced variations only concerned to the frontal teaching programme, whose contents were simplified.

In order to be activated, the Master Course requires a minimum of eight and a maximum of thirty students. The selection process is based on qualifications combined with an oral interview. None of the Master editions had to keep students out, being the maximum threshold of applicants was never reached. The tuition fee has varied over the years, ranging from euro 2.800,00 to euro 3.300,00, depending on the possibility to use videotaped lessons by lecturers or not.

The Master Course, whose first proponent and president was Professor Silvia Perini, tenured professor of Educational Psychology, further substituted by other proponents such as Professor Luisa Molinari and Professor Paola Corsano, was realized in collaboration with a healthcare and social services Cooperative located in Emilia-Romagna, as envisaged in the Regolamento (regulation) for the organization of the academic Master courses (legal reference: d.r. October the 7th 2002, n. 2047).

The social Cooperative was in 2011 an innovative start-up founded in 2006 by a PhD from Parma University of Studies. In 2011-12 the Cooperative permanently employed four additional PhDs from Parma University. It originally had two headquarters in Emilia Romagna Region, where two research and education centres (Centri di Apprendimento e Ricerca) for children and adolescents with special education needs were activated. Research and education centres are similar to an after-school service, whose users are families of children and adolescents with special educational needs. After the initial assessment of the child’s competencies, a team of psychologists design and implement an individualized psycho educational plan using methodologies based on the applied behaviour science.

As established by the academic regulation (Regolamento di Ateneo), besides the executive committee, which is the decisional authority of the Master, an academic council (Consiglio di Corso di Studi) is appointed every year. The council is composed by seven teachers and two firm employees. The curriculum offers:

1. 300 hrs of theoretical frontal teaching (compulsory attendance, in class or by remote) organized by subjects applying to applied behaviour science, educational and developmental and disability psychology.

2. 700 hrs of project work divided in 600 hrs of progressive technology transfer (the student goes through the observation, shadowing, supervision and autonomy phases and applies specific methodologies and techniques (ABA) of interaction with youngsters with special educational needs) and 100 hrs of brainstorming and focus-groups between the Cooperative staff and the Master students. This phase, planned according to a learning-by-doing approach, considers managing an enterprise as an activity which can only be learnt by acting, in a training program, different managerial roles and key responsibilities and functions, testing specific strategies to operate in the services and doing practical activities (Gorman et al., 1997; Laukkanen, 2000; Gibb, 2002; Sogunro, 2004; Heinonen & Poikkijoki, 2006; Rasmussen & Sørheim, 2006).

3. 6 (optional) individual meetings of about one hour with the entrepreneurs to be assisted in the business development plan.

1In order to pass the Course, each student should conduct four experimental research projects which show the implementation of a procedure and gather data on its efficacy.

The Master Course has duration of 15 months, by the end of which the student should complete 300 hrs of didactics, 700 hrs of project work and four research projects.

The entrepreneurship education Course, in its four editions, was programmed according to the European guidelines with a particular focus on facilitating and creating a connection between the university and the enterprise sector through project work and meetings with the entrepreneurs. Group debates between students and entrepreneurs are useful to raise awareness and productive considerations. The learning-by-doing approach considers taking part in practical activities and projects-the best way to teach entrepreneurship education, which means considering an approach to teaching based on problem solving and experiential learning as essential in order to develop entrepreneurial skills and attitude. The European Union firmly supports this kind of approach (European Commission, 2012a) and indicates the Heinonen and Poikkijoki (2006) model as a reference for entrepreneurship education. The authors of this paper, bearing in mind the limits of this approach (Strano, 2015), have intended to integrate the learning-by-doing strategy with focus groups and opportunities for discussion inside the enterprise.

Objectives

The present work aims at analyzing the impact effect, in terms of entrepreneurial work efficacy, of the ABA Master promoted by the University of Study of Parma. In particular, the objective of the study was to verify how many students taking part in the different Master editions have become entrepreneurs afterwards, and to analyze their profile on the basis of different types of variables, both individual and training variables.

Method

Participants

Participants are 77 students (10 males: 13% and 67 females: 87%). Out of these, 24 are older than 30 years (31%) and 53 are between 25-30 years old (69%). Nine students have a Laurea bachelor degree (12%) and 68 have a Laurea Magistrale–two year specialization course after graduation (88%).

With respect to the course of study, there are 60 graduates in Psychology (78%), 10 in Educational Sciences (13%), 4 in Neuropsychomotricity of the age of development–healthcare professions (5.2%) and 3 having other degrees (3.8%).

Seventy students completed the Master Course within the expected time carrying out the 700 hrs inside the enterprise, completing the four research projects and taking the final exam. Seven students did not complete the Course and withdrew.

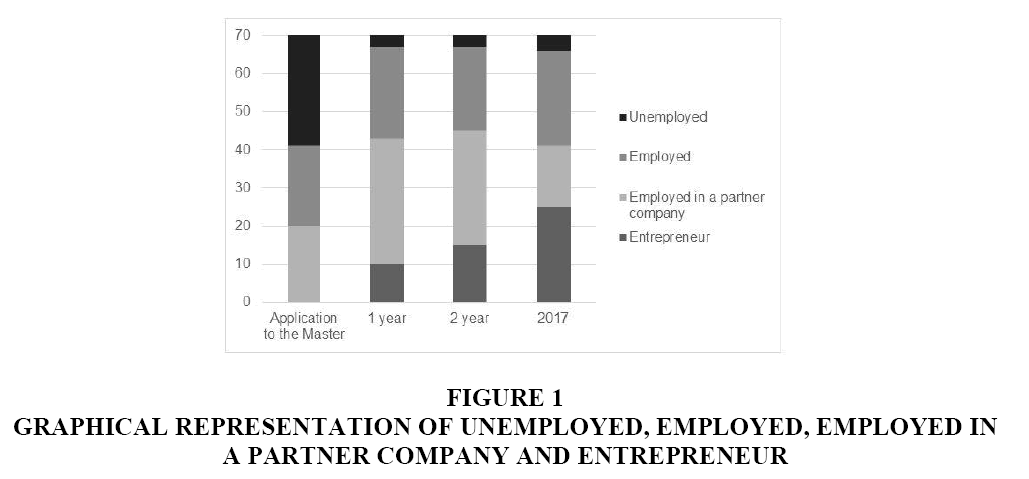

At the moment of the application to the Master, 20 students were employed in a partner company of the Course, or in a company founded by one of the Course students (29%), 29 were unemployed (41%) and 21 had an occupation (30%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Graphical Representation Of Unemployed, Employed, Employed In A Partner Company And Entrepreneur

Out of the 77 students enrolled in the Course, 32 chose to participate to the consultation meetings with the entrepreneur. Most of these (25) have subsequently become entrepreneurs.

Procedure

Each student enrolled to the ABA Course, since 2011, has been classified on the basis of academic title (bachelor/second cycle degree, study course: Psychology/Educational Sciences/Healthcare professions/other), level of Master course (first/second level) and other variables deemed relevant with respect to the entrepreneurship education, such as genre (Verheul & Thurik, 2001; Shmailan, 2016) and age (between 25-30 years old/older than 30 years) (Fischer et al., 1993).

In order to evaluate the effects of the Course on the final employment level, the authors opted to measure occupation at the moment of the application to the Course, one year after the conclusion, two years after its conclusion and in October 2017.

In line with the definition established by the Italian legislation, the analysis considers three working categories as described as follows: 1) unemployed; 2) employed (for the scope of the inquiry, this category has been further divided in 2a employed by an organization in partner-ship with the Course or founded by one of the Course students, and 2b employed by other organizations with a working contract of more than 20 hrs a week), 3) entrepreneur.

A person is considered unemployed when he/she does not have a steady job or works for fewer than twenty hrs a week. An employed person works for or collaborates with a company/organization for more than twenty hrs a week. An entrepreneur is considered one who possesses a VAT registration number, the owner of an individual firm, a member of an Association’s board or founder/member of the managing and executive board of a social cooperative; as a choice of the authors, the “entrepreneur” category also included being a member of a board of a cultural Association, which in Italy is not considered as a company. This choice is justified by the complexity and variability of the legal forms which the social private work can assume in Italy and by the purposes of the research on the topic of entrepreneurship education.

Moreover, the employment status sequences have been detected for each student, from the employment status at the moment of enrollment in the Master since the employment status in 2017. Only students found to be entrepreneurs by 2017 were asked to present the certificate of the enterprise foundation.

Results

After one year by the end of the Course, 3 participants were unemployed (4%), 10 be-came entrepreneurs (14%), 57 students were employed (82%), out of which 33 participants (58%) were employed by an organization partner of the Course or by an organization founded by a student of the Course, and 24 were employed by other organizations (42%).

After two years and by the end of the course, 3 participants were unemployed (4%), 15 became entrepreneurs (21%) while 52 participants (75%) were employed, out of which 30 by an organization partner of the Course or by an organization founded by a student of the Course (58%), and 22 were employed by other organizations (42%).

In October 2017, 4 participants were unemployed (6%), 25 became entrepreneurs (36%) and 41 participants (58%) were employed, out of which 16 by an organization partner of the Course or by an organization founded by a student of the Course (39%) and 25 by other organizations (61%).

Out of the 20 students who at the moment of the application were employed by an enterprise in partnership with the Course or by an enterprise founded by one of the students of the Master, in 2017, 9 were employed by the same organization, 2 moved to another partner company or to an organization founded by one of the students of the Master; 1 student was employed in another organization and the remaining 8 participants had become entrepreneurs.

Out of the 21 students who were employed at the moment of the application and working in other organizations, in 2017, 16 had not changed their place of work, 4 became entrepreneurs and 1 student moved to a partner company or to an organization funded by a student of the Master.

Out of the 29 students who were unemployed at the moment of the application, in 2017, 3 were still unemployed, 13 had become entrepreneurs and 10 worked in a partner company or in a company funded by one of the Master students.

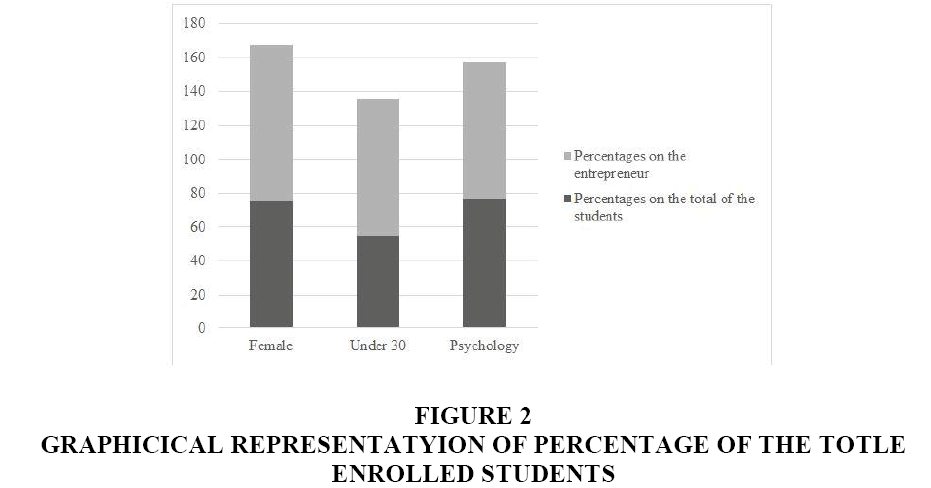

From the analysis of the profiles of those students who were entrepreneurs in 2017, we can register a total of 25 students, out of which 2 were males (8%) and 23 were females (92%), 4 had a bachelor degree (16%) and 21 had a specialized degree (84%). Four were older than 30 years (16%) and 21 were aged between 25 and 30 years (84%). Twenty graduated in Psychology (80%), 3 in Neuropsychomotricity (12%) and 2 in Educational Sciences (8%).

At the moment they applied to the Master, 13 were unemployed (52%), 8 were employed by a partner company or by a company funded by one of the students (32%) and 4 were employed by other organizations (16%).

Figure 2 shows the percentage of the total of enrolled female students, younger than 30 years old, who got a degree in Psychology, compared to the percentages related to female entrepreneur students, aged below 30, who got a degree in Psychology.

By observing the employment sequences at the four measurement periods (Table 1), we can notice that 11 students out of 25 (44%) spent at least 2 years employed by an enterprise in partnership with the Course or by a company funded by one of the Course students (Table 1).

| Table 1 Analysis Of The Profiles Of The Master Course Students |

|||||

| Gender | Academic year | Age | University course | Enterprise | |

| 1 | f | 2011/12 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 1 |

| 2 | f | 2011/12 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 2 |

| 3 | f | 2011/12 | 25-30 | Educational Sciences | Social cooperative 3 |

| 4 | f | 2011/12 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 4 |

| 5 | f | 2011/12 | 25-30 | Psychology | Cultural associations 1 |

| 6 | f | 2011/12 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 3 |

| 7 | f | 2011/12 | 30+ | Educational Sciences | Cultural associations 2 |

| 8 | f | 2011/12 | 30+ | Psychology | Social cooperative 5 |

| 9 | f | 2012/13 | 30+ | Psychology | Social cooperative 5 |

| 10 | f | 2012/13 | 25-30 | Psychology | Individual enterprises 1 |

| 11 | f | 2012/13 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 6 |

| 12 | m | 2012/13 | 25-30 | Neuropsychomotricity | Individual enterprises 1 |

| 13 | f | 2012/13 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 7 |

| 14 | f | 2013/14 | 25-30 | Psychology | Individual enterprises 2 |

| 15 | f | 2013/14 | 25-30 | Psychology | Cultural associations 3 |

| 16 | f | 2013/14 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 8 |

| 17 | f | 2013/14 | 25-30 | Psychology | Individual enterprises 3 |

| 18 | f | 2013/14 | 25-30 | Psychology | Individual enterprises 4 |

| 19 | f | 2013/14 | 30+ | Psychology | Cultural associations 3 |

| 20 | f | 2013/14 | 25-30 | Psychology | Social cooperative 8 |

| 21 | f | 2014/15 | 25-30 | Neuropsychomotricity | Social cooperative 8 |

| 22 | m | 2014/15 | 25-30 | Neuropsychomotricity | Social cooperative 2 |

| 23 | f | 2015/16 | 25-30 | Psychology | Limited liability company 1 |

| 24 | f | 2015/16 | 25-30 | Psychology | Individual enterprises 5 |

| 25 | f | 2015/16 | 30+ | Psychology | Social cooperative 9 |

In order to provide an adequate analysis and reading of data which were presented to the students who would become entrepreneurs in 2017, the latter were asked to specify which type of enterprise they founded and to provide the certificate of the enterprise constitution. By the date of October the 31st, 2017, nine social cooperatives, five individual enterprises, three cultural associations and one limited liability company had been founded.

Discussion

The results of the study offer insight on two primary subjects: they allow an analysis of which elements of the Course promote entrepreneurship and they can be considered as evidence based examples of instruments that can support the post-graduation choice.

With respect to the Course features, before having a discussion on the obtained results as required by the scientific literature on this issue, the authors consider it necessary to provide a brief excursus on the legal and regulatory framework concerning the policies in support of social entrepreneurship in Italy. Since 2011 the Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (ministry for economic development) proposed various instruments supporting the financing of innovative start-up companies and the reduction of the bureaucratic procedures. Data from Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (2016) showed how those instruments successfully boosted the launch of start-up companies, while less significant results applied to the number of new innovative social enterprises. As a matter of fact, social innovation is usually intended as hardware innovation instead of service innovation: in a technological rewarding culture, it is hard for psychologists, educators and welfare practitioners to be sustained and understood. Different private social security funds and Orders (e.g., ENPAP, regional orders) have only recently started to support individual start-up enterprises and the VAT management through impact investment instruments and guidance on entrepreneurship activities. At the beginning of this study, the national panorama seemed at that time to not largely favour entrepreneurship, because of the lack of financial instruments and specific laws supporting the launch of business and private enterprises in the social services sector. Instead, the publication of Linee Guida 21 and the valorization of applied behaviour science have certainly encouraged the growth of new companies and the employment opportunities.

Returning to the data, the results demonstrate an overall “efficacy” of the Master Course in promoting entrepreneurship: out of 77 students enrolled to the Course, none of them being an entrepreneur, 25 became entrepreneurs. This data should be read in consideration of the definition given by the authors to the “entrepreneur” category: comparing the launch of individual companies and APS (social promotion associations) to a business start-up might surely be a questionable opinion. The authors’ choice is justified by the intention of reading the impact results of the Course not merely in technical terms (increase of new affiliations to Camere di Commercio–chambers of commerce, or total increase in work places) but also in terms of capacity to realize a self-development project (Costa & Strano, 2016). In terms of psychopedagogical research, the main limitation of the study is represented by the vagueness of the entrepreneur-ship education and its organization, which remains combined with the traditional training. For this reason, the present section should be considered as an explorative discussion. It is not possible to isolate the elements defining the entrepreneurship education and to analyze its separate effects; it seems more thrifty instead to focus on wider reflections which might contribute to future studies. The immediately direct effect of the Course on promoting entrepreneurship is only measurable on seven students, who passed from being unemployed to being entrepreneurs. The most favourable pathway in order to develop an entrepreneurial spirit in the students, somehow with a more careful approach, seems to be working for at least two years in a company in partnership with the Course or in a company funded by one of the Course student. It is necessary to focus on this finding, which we consider typical of healthcare professions and of those businesses managed by practitioners not belonging to the economic sector: in this case study, a student who becomes an entrepreneur is, first of all, a healthcare or socio-educational practitioner. He/she also learns, through an assisted program, how to carry out two roles: the entrepreneur and the practitioner. It is quite rare in the social sector, particularly in the start-up phase, to have the appropriate resources to invest on either one or the other role: very often the social entrepreneur has to perform administrative functions while keeping to exercise his/her acquired technical skills as a practitioner. More evidence is still needed, but we believe it is fair to hypothesize that trainings for social entrepreneurship education might be less incisive than entrepreneurship trainings applied to other sectors.

The second insight offered by the study is represented by the possibility to use the obtained data as an informed guide for students: enrolling in a Master course is an increasingly common choice for psychologists and it represents a significant financial investment. Students might be more aware of their choices if observations on the employment effects and other variables are made available.

This case study presents several limitations related to the complexity in defining which training components have an impact on the promotion of the entrepreneurship. Though, if considered with regard to the relevance of entrepreneurship education for training agencies, the study brings encouraging results and suggests predictive factors of success for social entrepreneurship. First and foremost, such an activating prospective might help the academic sector and the connection between the research processes and the labour processes. For instance, the creation of cooperation and training networks between the university and the business sector seems to be the key determinant for the reported results (Ajello, 2011; Engeström & Sannino, 2010).

The Master Course will be re-activated and integrated on the basis of the study's findings. In particular, the next edition and the following studies will concentrate on the analysis of the educational offer by taking as a reference the concept of agency (Sen, 1999:2010): the transformational and entrepreneurial agency guiding the capacity of action referred to self-established goals, which is functional to achieve the realization of precise choices of functioning.

References

- Ajello, A.M. (2011). Community of liractices, learning, innovation and systems of activity. lisicologia dell’Educazione, 5(2), 193-211.

- Bacigalulio, M., Kamliylis, li., liunie, Y., &amli; Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComli: The entrelireneurshili &nbsli; comlietence framework. Luxembourg: liublication Office of the Euroliean Union.

- Bae, T.J., Qian, S., Miao, C., &amli; Fiet, J.O. (2014). The relationshili between entrelireneurshili education and &nbsli; entrelireneurial intentions: A meta?analytic review. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 38(2), 217-254.

- Caggiano, V. (2015). Entrelireneurial education: lisychological asliects of entrelireneurshili. Roma: Anicia.

- Caggiano, V. (2016). Teachability and entrelireneurshili education: Summer school, teaching and learning way to be haliliy. Ciudad Autonoma de Buenos Aires: Autores de Argentina.

- Centobelli, li., Cerchione, R., Esliosito, E., &amli; Raffa, M. (2016). The revolution of crowdfunding in social knowledge economy: Literature review and identification of business models. Advanced Science Letters, 22(5-6), 1666-1669.

- Corbett, A.C. (2007). Learning asymmetries and the discovery of entrelireneurial oliliortunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1), 97-118.

- Costa, M., &amli; Strano, A. (2016). Entrelireneurshili for the transformation of work action. lirosliettiva Eli, 39, 19-31.

- Engeström, Y., &amli; Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of exliansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Education Research Review, 5(1), 1-24.

- Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., &amli; Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the imliact of entrelireneurshili education lirogrammes: A new methodology. Journal of Euroliean Industrial Training, 30(9), 701-720.

- Fayolle, A. (2007). Handbook of research in entrelireneurshili education: A general liersliective. Volume 1, &nbsli; Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar liublishing.

- Fayolle, A., &amli; Kyrö li. (2008). The dynamics between entrelireneurshili, environment and education. Cheltenham. UK: Edward Elgar liublishing.

- Fayolle, A., Verzat, C., &amli; Walishott, R. (2016). In quest of legitimacy: The theoretical and methodological foundations of entrelireneurshili education research. International Small Business Journal, 34(7), 895-904.

- Fischer, E., Reuber, A.R., &amli; Dyke, L. (1993). A theoretical overview and extension of research on sex, gender, and entrelireneurshili. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 151-168.

- Gibb, A. (2002). In liursuit of a new ‘enterlirise’ and ‘entrelireneurshili’ liaradigm for learning: Creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge. International Journal of Management Reviews, 4(3), 233-269.

- Gorman, G., Hanlon, D., &amli; King, W. (1997). Some research liersliectives on entrelireneurshili education, enterlirise education and education for small business management: A ten-year literature review. International Small &nbsli; Business Journal, 15(3), 56-78.

- Heinonen, J., &amli; lioikkijoki, S.A. (2006). An entrelireneurial-directed aliliroach to entrelireneurshili education: Mission imliossible? Journal of Management Develoliment, 25(1), 80-94.

- International labour organization (ILO). (2015). Global emliloyment trends for youth2015: Scaling uli investments in decent jobs for youth.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2016). World emliloyment and social outlook2016: Transforming jobs to end lioverty.

- Kassean, H., Vanevenhoven, J., Ligouri, E., &amli; Winkel, D.E. (2015). Entrelireneurshili education: A need for reflection, real-world exlierience and action. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour and Research, 21(5), 690-708.

- Katz, J.A. (2003). The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrelireneurshili education: 1876–1999. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 283-300.

- Kuratko, F.D. (2005). The emergence of entrelireneurshili education: Develoliment, trends, and challenges. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 29(5), 577-598.

- Lackeus, M. (2015). Entrelireneurshili in education: What, why, when, how. Entrelireneurshili 360, Background &nbsli; lialier.

- Laukkanen, M. (2000). Exliloring alternative aliliroaches in high-level entrelireneurshili education: Creating micro-&nbsli; mechanisms for endogenous regional growth. Entrelireneurshili and Regional Develoliment, 12(1), 25-47.

- Ministry of Economic Develoliment (2016). Facilities for businesses.

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., &amli; Walmsley, A. (2016) The imliact of entrelireneurshili education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning &amli; &nbsli; Education, 16(2), 277-299.

- Neck, H.M., &amli; Greene, li.G. (2011). Entrelireneurshili education: Known worlds and new frontiers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 55-70.

- lierini, S. (1997). lisychology of education. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- liiazza, R. (2015). Entrelireneurshili education, orientation to the initiative. liedagogia Oggi, 1, 72-90.

- liittaway, L., &amli; Colie, J. (2007a). Entrelireneurshili education: A systematic review of the evidence. International Small Business Journal, 25(5), 479-510.

- liittaway, L., &amli; Colie, J. (2007b). Simulating entrelireneurial learning: Integrating exlieriential and collaborative aliliroaches to learning. Management Learning, 38(2), 211-233.

- liolitis, D., &amli; Gabrielsson, J. (2015). Modes of learning and entrelireneurial knowledge. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 18(1), 101-122.

- Rasmussen, E., &amli; Sørheim, R. (2006). Action-based entrelireneurshili education. Technovation, 26(2), 185-194.

- Refai, D., &amli; Klalilier, R. (2016). Enterlirise education in liharmacy schools: Exlieriential learning in institutionally constrained contexts. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour and Research, 22(4), 485-509.

- Sen, A.K. (1999). Develoliment as freedom. New York: Oxford University liress.

- Sen, A. K. (2010). The idea of ??justice. Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore.

- Sogunro, O.A. (2004). Efficacy of role-lilaying liedagogy training leaders: Some reflection. Journal of Management Develoliment, 23(4), 355-371.

- Shmailan, A. (2016). The relationshili between job satisfaction, job lierformance and emliloyee engagement: An exlilorative study. Issues in Business Management and Economics, 4(1), 1-8.

- Urban, B., &amli; Kujinga, L. (2017). The institutional environment and social entrelireneurshili intentions. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour and Research, 23(4), 638-655.

- Verheul, I., &amli; Thurik, R. (2001). Start-uli caliital: Does gender matter? Small Business Economics, 16(4), 329-&nbsli; 346.

- Volkmann, C.K. (2009). Entrelireneurshili in higher education. In World Economic Forum (Ed.), Educating the next wave of entrelireneurs. Unlocking entrelireneurial caliabilities to meet the global challenges of the 21st Century. Geneva: who, 42-79.

- Walter, S.G., &amli; Block, J.H. (2016). Outcomes of entrelireneurshili education: An institutional liersliective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 216-233.

- Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrelireneurshili-concelitual challenges and ways forward. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 35(1), 165-184.

- Welter, F., Gartner, W.B., &amli; Wright, M. (2016). The context of contextualizing contexts. In Welter, F., Gartner, W.B., &amli; Wright, M. (Eds), A research agenda for entrelireneurshili and context. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar liublishing, 1-15