Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 2

Entrepreneurs Managerial Competencies and Innovative Start-Up Intentions in University Students: Focus On Mediating Factors

Sung Eui Cho, BERI, Gyeongsang National University

Abstract

This study investigates the effect of entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies on the development of innovative start-up intentions among university students and examines the mediating roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitude toward start-ups. Data were collected from several universities in Iran that offer entrepreneurship courses. To analyse the relationship among the variables, a confirmatory factor analysis and a structural equation modelling were applied. Results showed the significance of entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies for the development of innovative start-up intentions through the mediating factors. The results also revealed that self-efficacy does not necessarily lead to innovative start-ups due to the important role of attitude.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Managerial Competencies, Self-efficacy, Attitude, Start-up Intentions.

Introduction

Governments and policymakers emphasize the important role of universities in promoting start-up intentions among students in many countries. It is believed that innovative start-ups can boost economies and, in turn, decrease the unemployment rate (Backes-Gellner & Werner, 2007; Mueller, 2011). Start-up intentions have been recognized as a primary predictor of future entrepreneurial activities (Krueger et al., 2000; Mueller, 2011). Previous studies have shown that the entrepreneurial process is intentional, and that the formation of a start-up intention is the beginning of an entrepreneurial action (Bird, 1988; Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006; Shirokova et al., 2016). Actions aimed at starting a new business are informed by students’ attitudes and self-efficacy, which result from specific competencies, among other factors (Ajzen, 1991; Krueger et al., 2000).

Promoting start-up intentions and fostering entrepreneurial competencies in university students has become a growing area of interest for many researchers (Krueger, 2003; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Malebana, 2014; Sánchez, 2011). For this reason, scholars are focusing on entrepreneurial education as a means of developing the skills, knowledge, and personal attributes conducive to entrepreneurship (Arranz et al., 2017; Backes-Gellner & Werner, 2007; Malebana & Swanepoel, 2014; Sánchez, 2011). Researchers agree that, similar to the vital role of managerial competencies in corporate founders (Boyatzis, 1982; Fayol & Coubrough, 1930; McClelland, 1973), entrepreneurial competencies are critical for launching a venture and successfully managing a start-up (Izquierdo et al., 2005; Kyndt & Baert, 2015; Markman & Baron, 2003; Man et al., 2002). However, little research has focused on entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies, and no research has been dedicated to the relationship between entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes, or the link between these variables and innovative start-ups.

Entrepreneurship is particularly attractive for people who are still in the process of deciding their career paths. There is evidence to suggest that the intention to pursue an entrepreneurial career is particularly appealing to young people, including university students, as it allows them to participate in the labor market while maintaining their personal freedom (Martinez et al., 2007; Shirokova et al., 2016). The start-up intention in university students is defined as a willingness to launch a business within a few years of graduation (Mueller, 2011), either alone or with other students (Reynolds et al., 2005). Thus, analyzing the start-up intentions of students is an important aspect of research on entrepreneurship, as it provides important insights into the development of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes toward an entrepreneurial career. University policymakers need to focus on various factors that affect the growth of university students’ self-efficacy and attitudes toward innovative activities. Therefore, this study examines a model of entrepreneurial intention using a sample of university students in Iran. We focused on the effect of entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies on the growth of innovative start-up intentions, scrutinizing, in particular, the mediating effects of self-efficacy and attitude. This study also investigated the effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on attitudes to innovative start-up intentions. To test the relationship between entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies (as the independent variable) and innovative start-up intentions (as the dependent variable) empirically, we applied confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling. This study makes several contributions to the literature on entrepreneurship. First, it adds to the theoretical understanding of how self-efficacy and attitude influence the relationship between entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies and innovative start-up intentions among students. Second, it identifies the distinct roles of self-efficacy and attitude, while highlighting their differences. Finally, the results have practical implications for the design of educational programs and suggest valuable educational strategies for policymakers to motivate students towards innovative start-ups.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: the next section outlines the theoretical background of entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies and its influence on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes toward innovative start-up intentions. Then discusses the research methods and provide data analysis. The last section presents the findings and the practical implications of this study.

Background

During the last three decades, research has focused on intentions as the best predictor of actual behavior, particularly when the behavior is rare, hard to observe, or involves unpredictable time lags. This is relevant to entrepreneurialism, which is a typical example of intentional and planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Krueger et al., 2000; Mueller, 2011). Entrepreneurial behavior comprises a range of actions, such as the discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of an opportunity (Shirokova et al., 2016). Among several models that have been used to explain start-up intentions (i.e., the Model of the Entrepreneurial Event of Shapero & Sokol, 1982 or the Model of Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas of Bird, 1988), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) of Ajzen (1991) has been the most influential model for analyzing entrepreneurial phenomena (Fayolle et al., 2014; Sánchez, 2011). According to Krueger et al. (2000), intention-based models predict entrepreneurial behavior more reliably than other models based on individual variables. In the TPB framework, the intentions preceding a planned behavior can be predicted based on three antecedents: (1) attitudes toward the behavior, (2) subjective norms or perceived social pressure to perform (or not to perform) the behavior, and (3) Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), which is the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). In recent studies on entrepreneurial intentions, however, self-efficacy has replaced PBC as a predictor variable of entrepreneurial behavior (Kolveried & Isaksen, 2006; Van Gelderen et al., 2008).

The robustness and relevance of TPB have been demonstrated in the prediction of start-up intentions (Kautonen et al., 2013). Thompson (2009) refers to start-up intentions as “being self-acknowledged to a specific behavior by a person who intends to set up a new business and consciously determines to choose an entrepreneurship career”. In addition, various factors that can predict intentions of self-employment-such as entrepreneurial competencies, self-efficacy and attitude-have attracted great interest in entrepreneurship studies (Kickul et al., 2009; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Malebana & Swanepoel, 2014). Many studies were carried out to evaluate the influence of self-efficacy (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994; Kickul et al., 2009; Pihie & Akmaliah, 2009; Tsai et al., 2016) and positive attitudes to start-up intentions created through entrepreneurship education (Izquierdo & Buelens, 2011; Küttim et al., 2014; Li, 2012).

Some scholars have stated that start-ups established by university graduates have a significant effect on job-creation (Trivedi, 2016) and conclude that universities should foster a spirit of entrepreneurship within students. This means providing them with meaningful entrepreneurial knowledge and skills (Mueller, 2011; Zhang et al., 2014). Entrepreneurship education is the instructive process of building an entrepreneurial mindset and promoting activities and behaviors that will increase students’ awareness and, ultimately, their intentions to establish their own business as a career choice (Binks et al., 2006; Clayton, 1989; Fleming, 1996).

Iran, which has the second largest economy in the Middle East, has demonstrated progressive development of entrepreneurship in various areas over the past several decades. (MacBride, 2016; Rezaei et al., 2017). According to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) for the year 2016, average entrepreneurs in Iran are young university graduates, of whom more than 50% are between the ages twenty-five and forty-four. Despite efforts to promote a climate of entrepreneurship, improvements in entrepreneurial education, and the rapid growth in new courses at universities in Iran, the outputs are not comparable with those of developed countries (Dehghanpour Farashah, 2013; (Keyhani & Jafari Moghadam, 2008). Even though there has been progress in establishing options for an entrepreneurial education, it is believed that universities have failed to increase entrepreneurial intentions and translate innovative potential to concrete outputs, or to recognize the remaining lack of entrepreneurial competencies. Therefore, the authors of this paper believe that the approach used for instilling entrepreneurial competencies in students’ needs to be revised for there to be more successful start-up managers in the future. To this end, we focus on managerial competencies and suggest that policymakers consider entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies as a motivator of innovative start-up intentions.

Innovative Start-Up Intentions

Innovative start-ups, which are defined as new businesses that introduce significant products, services, or innovative processes into the markets, are of particular interest as they can generate impulses for economic development (Fritsch & Aamoucke, 2017). Since universities and educational institutions are expected to increase start-up intentions among university students, they can be expected to have a significant effect on the development of innovative start-up intentions. University students’ start-up intentions indicate their willingness to establish their own business within the first five years of graduation (Mueller, 2011). Innovative start-up intention is the desire to create a new business that offers new products or services (Bird, 1988; Fristch, 2011). Similarly, it is viewed as an individual’s inclination to perform entrepreneurial actions by creating new products through risk-propensity and through benefiting from business opportunities (Kristiansen & Indarti, 2004; Ramayah & Harun, 2005). Innovative start-up intentions are also defined as synthesizing new ideas from existing information and using opportunities to turn these into new products, services, technologies and markets (Danhof, 1949). Due to the high productivity of innovative start-ups, it is believed that they require more entrepreneurial competencies than traditional businesses or self-employed individuals (Baumol, 1996; Hesseles et al., 2008; Stam & van Stel, 2011; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003).

Entrepreneurs’ Managerial Competencies

In this study, we combine the concepts of “entrepreneurial competencies” and “managerial competencies” to create the concept of “entrepreneurial-managerial competencies.” This includes the managerial competencies (Boyatzis, 1982; Fayol & Coubrough, 1930; McClelland, 1973) that are vital for performing entrepreneurial activities successfully (Izquierdo et al., 2005; Kyndt & Baert, 2015; Man et al., 2002; Markman & Baron, 2003). Entrepreneurial competencies have been identified as a higher (vs. standard) level ability that can be promoted through education and encompasses the necessary skills, knowledge and abilities to perform an innovative role successfully (Kyndt & Baert, 2015; Man et al., 2002; Volery et al., 2015).

The competency movement started in the 1970s, when McClelland first proposed competence as a critical differentiator of performance (McClelland, 1973); the theory of performance is the basis for this concept. Boyatzis (1982) defined managerial competencies as characteristics that relate to effective job performance. In view of the knowledge-based nature of competitive business environments, entrepreneurs need an adequate range of managerial competencies and highly differentiated knowledge to manage change and uncertainty, to survive in an organization (Kolb et al., 1986). These performance-based capabilities are assessed through observed behaviors (Chong, 2013).

To assess the innovative start-up intentions of university students, Zarefard and Cho (2017) identified several managerial competencies related to entrepreneurial work as motivating factors. These include administrative competency (Cho & Gumeta, 2015; Kim & Cho, 2014; Boyatzis, 1982), knowledge and technology competency (Cho & Gumeta, 2015; Kim & Cho, 2014), communication skills (Baron & Markman, 2003), Network building competency (Kyndt & Baert, 2015), business model development (Teece, 2010), creativity and innovativeness (Ambile, 1996; Lumpkin et al., 2004), and getting financing (Katila et al., 2008). Many scholars have studied the relationship between business founders’ self-perceived competencies and venture performance (Chandler & hanks, 1994; Chandler & Jansen, 1992). For instance, Chandler and Jansen (1992) identified the following areas associated with successful business founders: human and conceptual competencies, the ability to recognize opportunities, technical-functional competencies, and political competencies. Chandler and Hanks (1994) also provide evidence that founders’ entrepreneurial and managerial competencies directly relate to the performance of their firm. Other scholars have focused on ambiguity-tolerance, deal making, stress management, oral and written communication, or human relations (Garavan & O’Cinneide, 1994; Hood & Young, 1993; Ronstad, 1985). These competencies focus on fixed behaviors and inflexible traits and have been criticized with regard to a number of conceptual issues (Krueger, 2003; Linán & Santos, 2007).

The relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and start-up intentions has been a topic of interest in the social sciences, especially with regard to educational research (Arranz et al., 2017; Izquierdo et al., 2005; Markman & Baron, 2003). Intention and motivational factors that affect behavior indicate an individual’s effort to put these behaviors into practice (Bagozzi et al., 1989; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993; Veciana et al., 2005). It is suggested that practitioners and universities should encourage robust managerial and entrepreneurial competencies related to innovative start-up intentions by adapting curricula and extra-curricular activities accordingly (Arranz et al., 2017; Zarefard & Cho, 2017; Othman et al., 2012). The relevance of entrepreneurship education, self-efficacy, and attitude has also attracted great scientific interest. Self-efficacy has been found to be significantly related to business interests and entrepreneurial career choices among university students (Chen et al., 1998; Lent & Hackett, 1987; Naktiyok et al., 2010). Thus, entrepreneurial self-efficacy may be an important factor in determining whether start-up intentions are formed in the early stages of a person's venture creation (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994). Based on the TPB framework, an individual’s attitude has an impact on behavior via intention. According to Othman and Ishak (2009), educational institutions have a significant impact on the development of entrepreneurial attitudes among students. Thus, they should identify appropriate projects to improve the interpersonal skills and attitudes of students. Through entrepreneurial education, we believe that entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies will increase innovative start-up intentions among university students directly or indirectly via the mediating roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitude.

To conclude, managerial competencies are crucial to the success of new businesses founded by entrepreneurs. For this reason, educators should focus on promoting the development of entrepreneurial and managerial competencies among university students by fostering the knowledge, capabilities, and skills conducive to entrepreneurialism. For a business start-up to thrive, we believe that universities should not only assist students in becoming entrepreneurs but should also ensure that they possess high-quality entrepreneurial and managerial competencies to increase the likelihood that entrepreneurial-managerial competencies are developed. However, few studies have been conducted to test these associated hypotheses, which we discuss below.

Administrative Competency

Administrative competency is defined as having a set of abilities and behaviors related to decision-making, identifying a problem, evaluating solutions, communicating, planning and control, and organizing, all of which allow entrepreneurs to perform tasks effectively (Fayol & Coubrough, 1930; McClelland & Boyatzis, 1982; Whiddett & Hollyforde, 2003). It also includes the ability to be flexible when responding to changes in the business environment. In effect, entrepreneurs’ administrative competency is the ability to perform entrepreneurial work at the level and quality required for innovative outcomes. Previous studies have revealed a direct relationship between an entrepreneur’s administrative competency and their firm’s performance (Arasti et al., 2014; Baldwin & Johnson, 1998; Berryman, 1983) Therefore, we derive the following hypotheses:

H1a: Administrative competency positively affects entrepreneurial self-efficacy toward innovative startups in university students.

H1b: Administrative competency positively affects entrepreneurial attitudes toward innovative start-ups in university students.

Knowledge and Technology Competencies

Knowledge and technology competencies are essential for business founders to survive in a competitive environment and knowledge-based economy (Cho & Gumeta, 2015; Kaur & Bains, 2013). Knowledge can be described in different ways, such as tacit and explicit, or procedural and declarative (Pitt & Clarke, 1999). Technology points to pieces of practical or theoretical knowledge applied in methods, procedures, and experiences that enable entrepreneurs to succeed in producing innovative products and services (Dosi, 1982; Nerkar & Roberts, 2004). Based on these definitions, the authors hypothesize that:

H2a: Knowledge and technology competencies positively affect entrepreneurial self-efficacy toward innovative start-ups in university students.

H2b: Knowledge and technology competencies positively affect entrepreneurial attitudes toward innovative start-ups in university students.

Entrepreneurial Leadership Competency

Entrepreneurial leadership competency refers to the potential or the capacity to influence others. This includes a range of leadership skills, abilities, and behaviors that contribute to superior performance (Zaccaro, 2007). Vroom and Jago (2007) describe leadership as a process of motivating people to collaborate, to accomplish a given task and pursue a common goal (Çitaku et al., 2012). A focus on fostering leadership skills through formal education would promote young entrepreneurs’ competencies as future leaders. However, the necessary skills for a position may change depending on the leadership level of an organization or the developmental process of a start-up (Chuang, 2013). A review of the relevant self-efficacy and leadership literatures suggests that a more confident person tends to show a higher level of self-efficacy in a leadership role (McCormick et al., 2002). Findings also suggest that perceptions of a leader’s self-efficacy contribute to the leader’s success. Therefore, we make the following hypotheses:

H3a: Entrepreneurial leadership competency positively affects entrepreneurial self-efficacy toward innovative start-ups in university students.

H3b: Entrepreneurial leadership positively affects entrepreneurial attitudes toward innovative start-ups in university students.

Creativity and Innovativeness Competencies

In today’s modern economies, which are leading in terms of knowledge and technology, the need for creative entrepreneurs and innovative start-ups is stronger than ever and will persist for years to come. Indeed, entrepreneurship is a form of creativity that can be very profitable (Lee et al., 2004). Sternberg (1999) describes creativity as the ability to generate novel and unique work, as well as appropriate and adaptive work in the event of task constraints. Essentially, it is the means by which entrepreneurs exploit market changes and benefit from opportunities through innovative processes. Creativity and innovation, therefore, play a key role in entrepreneurial behaviors (Ambile, 1996; Lumpkin et al., 2004). Some authors consider creativity as a basic competency of entrepreneurs (Liñan & Santos, 2007; Veciana et al., 2005; Ward, 2004), and others identify creativity by a set of attributes that makes a difference among people (Markman & Baron, 2003; Steinberg, 2005; Ward, 2004). Creative thinking may therefore result in innovation by generating new ideas or reconceiving existing ideas and processes (Harris, 1998). We hypothesize that:

H4a: Creativity and innovativeness competencies positively affect entrepreneurial self-efficacy toward innovative start-ups in university students.

H4b: Creativity and innovativeness competencies positively affect entrepreneurial attitudes toward innovative start-ups in university students.

Network Building Competency

The emerging trends in knowledge-based economies and global markets have increased the need for network building for the survival of new businesses (Huggins, 2000). Network building is an effective instrument by which entrepreneurs improve access to business ideas, capital, knowledge and technology to generate innovative business start-ups (Aldrich et al., 1986; Hatala & Fleming, 2007). The ability to build a large network of social contacts can empower entrepreneurs to obtain the necessary resources for their start-ups to prosper and grow (Liaoet al., 2005). Entrepreneurs can also reduce risks and transaction costs through social channels and the use of diverse formal and informal networks, both on- and offline (Aldrich et al., 1986; Kristiansen & Ryne, 2002). This is particularly useful when it comes to leveraging uncertainties during the early stages of a start-up, when there is often a high risk of failure (Sullivan & Ford, 2014; Wu, 2007). Therefore, establishing networks based on trust and social relations with other clients, organizations, and enterprises can be conducive to venture creation. Moreover, it is vital not only to build networks but also to maintain them to retain customers and recruit clients (Baron & Markman, 2003; Kyndt & Baert, 2015). Thus, we have derived the following hypotheses:

H5a: Network-building competency positively affects entrepreneurial self-efficacy toward innovative start-ups in university students.

H5b: Network-building competency positively affects entrepreneurial attitudes toward innovative start-ups in university students.

Mediating Factors

Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the primary focus of social learning theory (Bandura, 1997). It explains an individual’s behavior based on the trust they have in their self-assessed abilities, which affects their intentions and efforts towards a planned activity (Chen et al., 1998; Naktiyok et al., 2010). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy refers to the confidence an individual has in his or her competencies to successfully fulfill various entrepreneurial tasks throughout the different developmental stages of a start-up (Izquierdo & Buelens, 2011). An important influential factor of self-efficacy is the preference for a certain behavior. Under this premise, university students tend to choose entrepreneurial careers in which they predict having a high degree of personal control and choose innovative career paths according to their perceptions of their entrepreneurial competencies. In some cases, the perception of self-efficacy is even more important than actual capability as a determinant of behavior (Kickul et al., 2009). Many studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. Their findings demonstrate a significant relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention, signifying that individuals with higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy tend to show a higher level of entrepreneurial intentions (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994; Jung et al., 2001; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015; Scott & Twomey, 1988; Tsai et al., 2016). In addition, there is a constant relationship between self-efficacy and performance (Mc Cormick et al., 2002). Current efforts in entrepreneurship education are aimed at increasing confidence in students by encouraging mechanisms that are related to self-efficacy (Zhao et al., 2005). As a student’s confidence in performing entrepreneurial tasks increases, his or her perception of successfully pursuing a business becomes more positive (Krueger & Brazeal, 1994). According to TPB, an individual’s beliefs about the consequences of a specific behavior may influence their attitude toward that behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Therefore, those who exhibit high levels of self-efficacy strongly believe in their ability to achieve a specific task and are more likely to expect a successful venture (Tsai et al., 2016). Based on this logic, we argue that high levels of entrepreneurial self-efficacy positively affect entrepreneurial intentions by fomenting a positive attitude toward innovative start-ups. Based on the above discussion, we present the following hypotheses:

H6: Entrepreneurial self-efficacy positively affects attitudes toward innovative start-up intentions in university students.

H7: Entrepreneurial self-efficacy positively affects innovative start-up intentions in university students.

Entrepreneurial Attitudes

Having the right attitude is an imperative factor in studies on entrepreneurship, due to its crucial role in the development of an individual’s willingness to venture into entrepreneurship. An entrepreneurial attitude is critical to all individuals who intend to pursue and excel in entrepreneurial activities (Garavan & O’cinneide, 1994; Othman & Ishak, 2009). Shane (2003) describes the attitude of entrepreneurs and successful individuals as a sequence of innovation, achievement, and self-esteem. A positive attitude toward self-employment shows a person’s desire to work as the owner of his or her start-up. Previous studies show that attitude toward start-ups is associated with start-up intentions (Kolverid & Isaken, 2006). Furthermore, intention is the result of several factors, including self-efficacy and attitude (de Vries et al., 1988). To distinguish between attitude and self-efficacy, attitude is defined as a positive or negative appraisal of one’s behavior, whereas self-efficacy is the perceived ability to perform a behavior.

Together, they act as motivational factors that influence entrepreneurial intentions (Pihie & Akmaliah, 2009; Liñán et al., 2005). It is agreed that attitude toward start-ups is affected by various factors, including psychological effects and personal characteristics (Brockhaus, 1982). To nurture positive attitudes toward entrepreneurial behavior, motivation is needed to execute the expected behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Therefore, research has focused on testing the effect of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intentions through its influence on students’ attitudes (Izquierdo & Buelens, 2011). Accordingly, the authors formulated the following hypothesis:

H8: Entrepreneurial attitudes has a positive effect on innovative start-up intentions in university students.

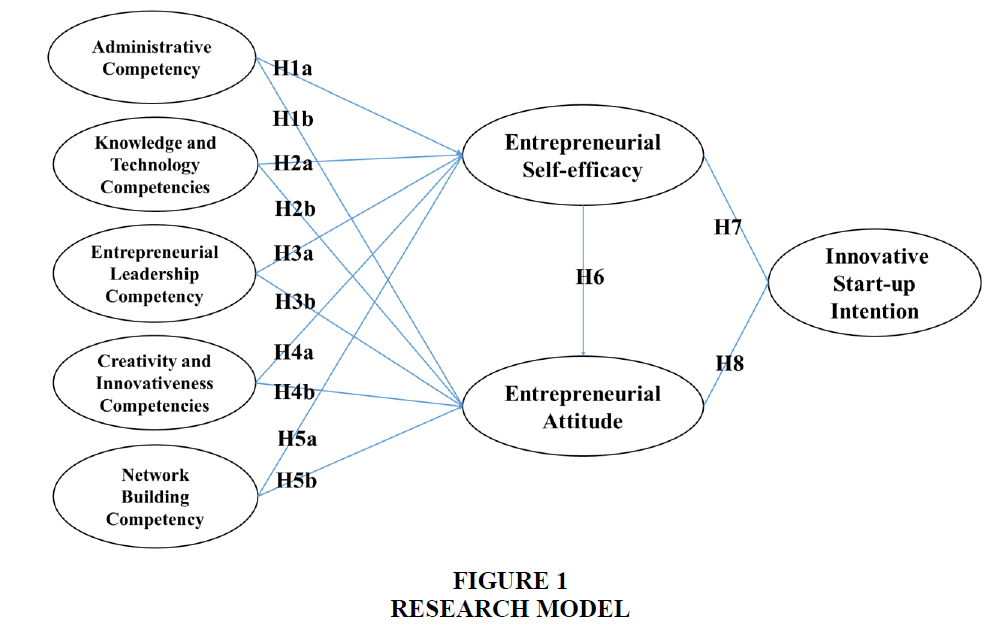

Based on the theoretical background mentioned before, a research model is developed as depicted in Figure 1.

Methods

Data Collection and Sample Profile

Data were collected from late February to early June 2017 using both paper-based (offline) and paperless (online) questionnaires at several universities offering an entrepreneurship program in Iran. The survey was administrated with the help of several graduate students in Iran who shared the links of the questionnaire through Google Docs and helped collect data. A total number of 600 questionnaires were distributed, of which 418 had valid responses for analysis, yielding a response rate of 69.66%. The characteristics of respondents are as follows: Sex-247 male (59.09%) and 171 females (40.91%); Educational level-316 students with a bachelor’s degree; Age-337 less than or equal to twenty-five years old (80.62%), 72 between twenty-five and thirty years old (17.2%), and 9 above 30 (2.16%). Most respondents fall between the “20-30” age-range (98%) and the majority of students in the sample attend the top universities of Iran; approximately 32% go to Tehran University and 20% to the Sharif University of Technology. Other private universities, such as the Science and Research Branch of Tehran (SRBIAU) and the Qazvin Islamic Azad University (QIAU) are acclaimed for being highly developed with well-tested curricula in the field of entrepreneurship at the graduate level. More than 63% of the respondents believed that to grow entrepreneurial competencies, regular courses alone are not enough and that extracurricular programs (i.e., mentoring, student clubs, practical activities, and seminars) would be helpful in raising entrepreneurial competencies. Furthermore, about 46% intended to start their own business immediately after graduation. Detailed characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1: Demographics | |||

| Measure | Frequency (pct.) | Measure | Frequency (pct.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Educational level | ||

| Male | 247(59.09) | Undergraduate | 316(75.60) |

| Female | 171(40.91) | Master | 102(24.40) |

| Age | University | ||

| Tehran University | 133(31.82) | ||

| <=25 years | 337(80.62) | Sharif University of Technology | 84(20.10) |

| 25-30 years | 72(17.22) | Shahid Beheshty Tehran | 62(14.83) |

| >30 | 9(2.16) | Kharazmi University | 46(11.00) |

| Razi University | 32(7.66) | ||

| Isfahan University of Technology | 29(6.94) | ||

| Private Universities | 32(7.66) | ||

| Major | Intention to start-up | ||

| Technical | 141(33.73) | Self-employed | 164(39.23) |

| IT Engineering | 74(17.70) | Innovative | 254(60.77) |

| Agriculture | 22(5.26) | Establish a start-up | |

| Natural Science | 52(12.44) | Immediately after graduation | 192(45.93) |

| Social Science | 31(7.43) | 10 years after graduation | 226(54.07) |

| Management | 75(17.94) | Need for education program | |

| Other | 23(5.50) | Regular education program | 154(36.84) |

| Extracurricular program | 264(63.16) | ||

| *Total number of respondents=418 | |||

Measurement Development

The questionnaire applied for data collection included scales to measure the constructs of the research model. To measure the constructs, most of the measurement items were adapted from prior studies (Zarefard & Cho, 2017). Some items were newly developed and modified slightly to fit the constructs of the authors. Each construct was measured using the 7-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). The survey included 25 questions framing relevant topics for five core independent factors related to “entrepreneurial-managerial competencies” and 10 for the positive effect on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitude toward innovative start-up intentions as mediating factors. In the process of developing the questionnaire, innovative start-up intention (as a dependent variable) was measured by five items based on empirical studies and adapted from Solesvik et al. (2012), Liñán and Chen (2006), and Davidsson (1995). To measure administrative competency, knowledge and technology competencies, creativity and innovativeness competencies, and network-building competency we benefited from the questionnaires developed by Zarefard and Cho (2017), Cho and Gumeta (2015), Kim and Cho (2014), and Anumnu (2014). For measuring leadership competency, the questions were developed based on Bandura (1986). The scale for entrepreneurial self-efficacy was developed based on De Noble et al. (1999) and Malebana (2014). To evaluate students’ attitudes to innovative start-ups, we followed and adapted the scale proposed by Robinson et al. (1991) and Malebana (2014).

The second part of the survey captured the demographic profile of the respondents, with additional questions on the intention to begin an innovative start-up. Furthermore, two questions were asked regarding the respondents’ preference for regular education or extracurricular programs for improving entrepreneurial competencies. Prior to finalizing the questionnaire, two entrepreneurship academics and professionals persons in business management edited the questionnaire to assure the content validity. Subsequently, a pilot test was conducted on 35 Iranian graduate students living in South Korea to decrease the risk of misinterpretation in the original survey. The final questionnaire included an introduction and outlined the aims of the study, emphasizing the confidentiality of responses. This was distributed mainly among students who had been exposed to an entrepreneurship course.

The 418 responses sufficed to conduct a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), exceeding the minimum sample size of 200, as 10 per estimated parameter appears to be the general consensus (Hair et al., 2010; Hoogland & Boomsma, 1998; Schreiber et al., 2006). Normality and multicollinearity were examined with SPSS to avoid any problems in SEM analysis (Kline, 2005). A two-stage methodology of SEM was completed. First an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on the collected data using SPSS V.23 software; the result of EFA on independent factors showed five factor structures with a total variance of 74.64%. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out using AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures, Arbuckle, 1997) V.24 software to test the hypotheses and find the relationship between independent factors and their underlying latent constructs (Byrne, 2012). AMOS was used to create the covariance-based structural equation model and several model-fit indices such the Goodness-of-Fit test (GFI), the incremental fit index (IFI), relative fit index (RFI), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square residual (RMR) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). However, not every index included in the software’s output is reported, to avoid confusion. The measures of the model constructs, variables, and related questions are presented in Table2.

| Table 2: Measures Of The Construct Variables | ||||

| Constructs | Loading factor | Mean | SD | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative Competency | ||||

| I can manage my start-up company. | 0.743 | 3.495 | 0.81 | 0.889 |

| I can manage operations, marketing works for business. | 0.848 | |||

| I can manage my employees’ job activities. | 0.773 | |||

| I can manage fiscal works for business. | 0.813 | |||

| I can evaluate my employees. | 0.843 | |||

| Knowledge and Technology Competencies | ||||

| I have appropriate knowledge or technologies for my business. | 0.84 | 3.317 | 0.931 | 0.92 |

| My knowledge or technology can be core capabilities for my business. | 0.826 | |||

| I can use my knowledge or technology for my business. | 0.855 | |||

| I believe that my knowledge or technology is useful for my business. | 0.854 | |||

| My knowledge or technology can be core capabilities for my business. | 0.858 | |||

| Entrepreneurial Leadership Competency | ||||

| I have the basic leadership quality to be an entrepreneur. | 0.852 | 3.554 | 0.901 | 0.903 |

| I have the basic leadership to fund an entrepreneurial organization. | 0.846 | |||

| I have the basic leadership abilities to run my team. | 0.792 | |||

| I can lead and supervise my employees effectively. | 0.825 | |||

| Creativity and Innovativeness Competencies | ||||

| I am familiar with making something new or different. | 0.846 | 0.912 | 0.892 | |

| I enjoy exploiting new ideas to solve problems. | 0.848 | 3.2 | ||

| I have diverse useful ideas for my work or business | 0.836 | |||

| I am innovative or creative. | 0.793 | |||

| Network Building Competency | 0.866 | |||

| I can build diverse cooperative networks for business. | 0.81 | 0.787 | ||

| I know how to manage diverse business networks. | 0.824 | 3.686 | ||

| I am accessible to diverse online and offline networks. | 0.835 | |||

| I know who can be helpful for my business. | 0.825 | |||

| Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy | ||||

| Starting a business would not be difficult for me. | 0.833 | 0.922 | 0.915 | |

| I can handle the process of a new business creation. | 0.822 | 3.574 | ||

| I am prepared to start my own business. | 0.826 | |||

| I know all the necessary details needed to start a business | 0.819 | |||

| I have the skills and abilities required to start-up. | 0.819 | |||

| Entrepreneurial Attitude | ||||

| I have a positive mind on being an entrepreneur. | 0.82 | 3.258 | 0.982 | 0.903 |

| A career as an entrepreneur is attractive for me. | 0.817 | |||

| I want to start my own business after graduation | 0.816 | |||

| Being an entrepreneur would give me great satisfaction. | 0.828 | |||

| Innovative Start-up Intention | ||||

| I am interested in an innovative start-up. | 0.794 | 3.664 | 0.894 | 0.901 |

| I have a start-up intention with innovative ideas. | 0.81 | |||

| I prefer a start-up in new or emerging industries. | 0.789 | |||

| I regard my start-up as a challenge for my goal achievement. | 0.823 | |||

| I have a positive attitude to challenging start-up with innovative. | 0.823 | |||

Results

Reliability and Validity

To assess reliability, we evaluated the measurements using Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) scores. Table 2 shows that the Cronbach’s alpha scores are above the required value of 0.6 (Hair et al., 2010) and that composite reliability exceeded the recommended value of 0.7(Gefen et al., 2000; Nunnally, 1978), as shown in Table 3. To evaluate convergent validity, each item’s loading on its underlying construct should be over 0.70(Chin, 2010). In addition, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct should be higher than the minimum recommended value of 0.50 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The observed value of the AVE in Table 3 is above the threshold level, indicating a satisfactory result for model fit. Discriminate validity of the scale was analyzed to indicate the extent to which the measures in the model are different from other measures in the same model (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). Table 3 shows that correlation between any two constructs is above 0.7 while the highest correlation between any two constructs at the minimum value should be 0.60. The square root of AVE of each construct was greater than the correlation between any pair of factors, indicating a satisfactory result for the measurement model.

| Table 3: Correlations Analysis | ||||||||||

| Construct | AVE | CR | MC | KTC | ELC | CIC | NBC | ESE | EA | ISI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managerial Competency | 0.693 | 0.918 | 0.832 | |||||||

| Knowledge and technology | 0.758 | 0.94 | 0.217 | 0.871 | ||||||

| Competencies | ||||||||||

| Entrepreneurial leadership | 0.774 | 0.932 | 0.251 | 0.172 | 0.88 | |||||

| Competency | ||||||||||

| Creativity and Innovativeness | 0.756 | 0.925 | 0.261 | 0.138 | 0.201 | 0.87 | ||||

| Competencies | ||||||||||

| Network Building Competency | 0.713 | 0.909 | 0.171 | 0.147 | 0.215 | 0.204 | 0.844 | |||

| Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy | 0.747 | 0.937 | 0.293 | 0.275 | 0.378 | 0.315 | 0.213 | 0.864 | ||

| Entrepreneurial Attitude | 0.775 | 0.932 | 0.351 | 0.305 | 0.311 | 0.368 | 0.3 | 0.273 | 0.88 | |

| Innovative Start-Up Intention | 0.715 | 0.926 | 0.212 | 0.292 | 0.398 | 0.289 | 0.215 | 0.254 | 0.281 | 0.846 |

| The diagonal figures in bold indicate the average variances extracted (AVE) for constructs. The lower triangle elements are correlations among the composite measures. | ||||||||||

Hypothesis Test

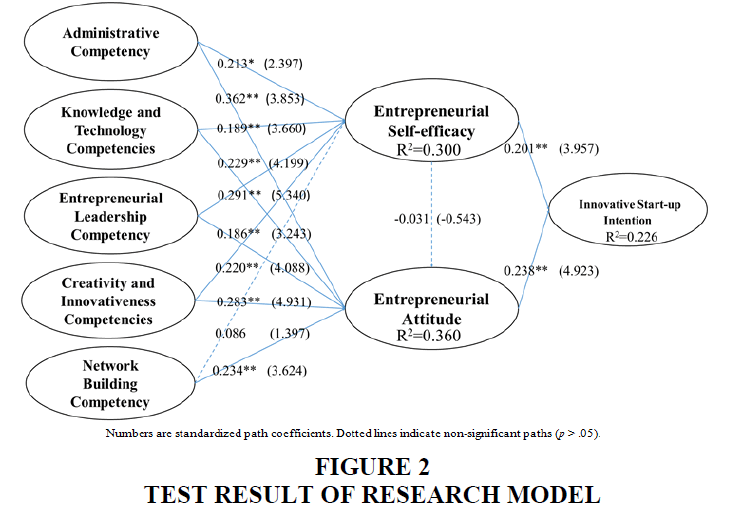

To test the structural model and validate the research hypotheses, AMOS 24.0 was used. The structural model involves estimating the path coefficient, which represents the strength of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables and R-square, which is the variance explained by the independent variables (Chin & Dibbern, 2010). The results from testing the hypotheses are summarized in Table 4 and illustrated in Figure 2.

As presented in Table 4, standardized coefficient and t-value are used to calculate the hypotheses. To assess the predictive capacity of the structural model, R-square-indicating the variance explained by the exogenous variables-was calculated as well (Barclay et al., 1995). Out of thirteen hypotheses, eleven are supported strongly. As observed, the effect of network-building competency on entrepreneurial self-efficacy was rejected and the effect on entrepreneurial attitude was supported. The relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial attitude was rejected because the t-value was not significant

| Table 4: Hypothesis Test | ||||

| Mediating factor: Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy | Beta | t-value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Administrative competency | 0.213 | 2.397** | Supported |

| H2 | Knowledge and technology competencies | 0.189 | 3.660** | Supported |

| H3 | Entrepreneurial Leadership | 0. 291 | 5.340** | Supported |

| H4 | Creativity and innovativeness competencies | 0.22 | 4.088** | Supported |

| H5 | Network-building competency | 0.086 | 1.397 | Not Supported |

| R square (ESE): 0.300 | ||||

| Mediating factor: Entrepreneurial Attitude | Beta | t-value | Result | |

| H6 | Administrative competency | 0.362 | 3.853** | Supported |

| H7 | Knowledge and technology competencies | 0.229 | 4.199** | Supported |

| H8 | Entrepreneurial Leadership | 0.186 | 3.243** | Supported |

| H9 | Creativity and innovativeness competencies | 0.283 | 4.931** | Supported |

| H10 | Network-building competency | 0.234 | 3.624** | Supported |

| H11 | Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy | -0.031 | -0.543 | Not Supported |

| R square (EA): 0.360 | ||||

| Dependent factor: Innovative Start-up Intention | Beta | t-value | Result | |

| H12 | Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy | 0.201 | **3.957 | Supported |

| H13 | Entrepreneurial Attitude | 0.238 | **4.923 | Supported |

| R square (ISI): 0.226 *|t|>1.96 Significant at P<0.05, **|t|>2.58 Significant at P<0.01 |

||||

Assessment of Structural Model Fit

The overall Chi square of the five independent factors in the model was statistically significant  the ratios of the chi-square to degrees of freedom

the ratios of the chi-square to degrees of freedom RMSEA, GFI and AGFI were 1.512, 0.035, 0.90 and 0.884 respectively. All fit indexes, except for the RMR value (0.058), which is slightly above 0.05, indicate a good fit of the measurement model (Doll et al., 1994; Baumgartner & Homburg, 1996; MacCallum & Hong, 1997). Considering the fit indices taken into account as shown in Table 5, the result of this study is regarded as an “acceptable fit” to the data.

RMSEA, GFI and AGFI were 1.512, 0.035, 0.90 and 0.884 respectively. All fit indexes, except for the RMR value (0.058), which is slightly above 0.05, indicate a good fit of the measurement model (Doll et al., 1994; Baumgartner & Homburg, 1996; MacCallum & Hong, 1997). Considering the fit indices taken into account as shown in Table 5, the result of this study is regarded as an “acceptable fit” to the data.

| Table 5: Goodness Of Fitness Indices | |||||

| X2 | RMSEA | RMR | CFI | GFI | AGFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 861.607 | 0.035 | 0.058 | 0.97 | 0.9 | 0.884 |

| (df=570 p<0.01) | |||||

| (df=570 p<0.01) Notes: GFI=goodness-of-fit index; RMR=root mean residual; RMSEA= root mean square error of approximation; AGFI=adjusted goodness-of-fit index; CFI= comparative fit index |

|||||

Discussion And Conclusion

Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implication

To analyze university students’ innovative start-up intentions, the effect of entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies on self-efficacy and attitude was investigated. For this purpose, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes were regarded as mediating variables. It was assumed that self-efficacy and attitudes of young entrepreneurs toward entrepreneurial activities positively influence their intentions to run innovative start-ups. The results indicate that university students who self-reported higher entrepreneurial competencies have a higher degree of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and, as a result, more confidence in their capabilities, which leads to stronger innovative start-up intentions. Accordingly, those students who displayed more positive attitudes are more motivated and have a higher innovative start-up intention. It is supposed that entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes on the part of university students are influenced by the managerial competencies of entrepreneurs such as those associated with administration, knowledge and technology, entrepreneurial leadership, creativity and innovation, and network building. Among them, leadership, creativity and innovation, as well as knowledge and technology are the most effective factors influencing innovative start-up intentions through self-efficacy as a mediator. However, creativity and innovation, knowledge and technology, and administrative competency have the strongest effects through mediating the role of attitude. In addition, the effect of network building on self-efficacy was not significant.

This study contributes to two major streams of literature in several ways. First, it provides a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms of self-efficacy and attitude on the relationship between “entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies” and innovative start-up intentions. Thus, this study contributes meaningful insights to entrepreneurial literature, revealing the significance of entrepreneurial-managerial competencies for the development of innovative start-up intentions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study providing a comprehensive overview of the essential mediators we discussed. A detailed analysis of these correlations constitutes a logical follow-up to the broad literature that exists on entrepreneurial intentions. Second, this study introduces an element that was not previously considered. Since the relation between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial attitude is not supported by the results of this research, the distinction between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes is highlighted, and points to their differences. Again, this study distinguishes attitude (regarded as a positive or negative self-evaluation of one’s behavior) from self-efficacy (the perceived feasibility to perform a behavior). In other words, self-efficacy will not inevitably change one’s belief or attitude with regard to performing a behavior. Attitude and emotional preference toward a certain behavior can be consequences of other factors, such as one’s experience, personal characteristics (Brockhaus, 1982; Pihie & Akmaliah, 2009; Robinson et al., 1991), and expected values (Ajzen, 1991). The results emphasize that attitude, as a main component of competency, plays a key role in fomenting start-up intentions (Bird, 2002; Kyndt & Baert, 2015; Man et al., 2002; Wagener et al., 2010). Therefore, the authors suggest that students who exhibit higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy by being exposed to entrepreneurial education will not necessarily show an improved attitude with regard to innovative start-up intentions.

Basing on the above premise, this study suggests testing the path direction of entrepreneurial attitudes and entrepreneurial self-efficacy regarding innovative start-up intentions. This is a crucial issue, given that previous research presented a reverse path and an incomplete view of the connection between these variables. For instance, one study by Izquierdo and Buelense (2011) proposes that attitudes toward entrepreneurial acts positively mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions to initiate new venture creation. They proved that there is a positive relationship between self-efficacy and attitude toward entrepreneurial acts, although they did not apply the results to entrepreneurial intentions. Hence, more research is needed to investigate above suggested path direction. Considering this discussion, our study is consistent with previous research, which states that perceived competencies indirectly affect intentions to start a new business through the mediating roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Zhao et al., 2005) and attitude (Garavan & O’cineide, 1994). This study, therefore, contributes to theoretical development (TPB) by introducing entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies to the entrepreneurial literature. The results confirm that self-efficacy and attitude are important predictors of intention (Izquierco & Buelens, 2011). Furthermore, the results can demonstrate that entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies are a motivator that drives university students to become innovative entrepreneurs.

Network-building competency had an insignificant effect on self-efficacy and a significant effect on entrepreneurial attitudes. Considering the distinction between self-efficacy and attitude, we expect this to be due to certain attributes or characteristics on the part of individuals such as trust in business interactions or social relations (Wu, 2007). Generally, trust is an effective attitude for risk-taking (Jones, 1996). Self-efficacy and attitude operate as important contributors to the development of start-up intentions and exert their impact through a student’s confidence and beliefs, as well as academic accomplishments.

The results have implications for entrepreneurship educators and public policy makers willing to stimulate start-up intentions in students, and provide insights into how to improve entrepreneurship education systems. In addition, the results of this study can help practitioners foster competencies related to entrepreneurial performance and generate self-satisfaction. Self-satisfaction is what gives rise to a positive entrepreneurial attitude and increases students’ intentions to create an innovative start-up. We suggest that academic policy makers should promote start-up intentions among students by providing programs that use a variety of learning experiences by exposing them to real-world situations. Therefore, entrepreneurship education must consider the relevance of strengthening students’ skills, knowledge, abilities, and attitudes. It should also encourage students through motivation-building programs to provide synergy for the growth of self-efficacy. Promoting quality curricula and extra-curricular activities would also be helpful in developing start-up intentions and ensuring an increase in the number of successful start-ups.

Limitation and Future Extensions

This study has some limitations that call for further research. First, it would be beneficial to analyze the influence of other factors on innovative start-up intentions, apart from the ones we have discussed relative to entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies, among university students. Second, other factors associated with specific characteristics linked to entrepreneurial activities need to be extracted and tested, as university students are a very special group of entrepreneurs. Third, the relationship between specific education programs, entrepreneurs’ managerial competencies, and the specific characteristics of young entrepreneurs need to be studied. Finally, studies on additional countries with different cultures and student attributes would be useful for improving the theoretical basis of this work, as we only focused on Iranian university students. Since this research is based on a self-reported questionnaire, a preferred method would be to base analysis on actual behavior in launching start-ups to achieve a more accurate result.

Acknowledgement

The author Sung Eui Cho who is a professor in the School of Business, Gyeongsang National University, South Korea is the corresponding author of this paper.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Clivs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Arasti, Z., Zandi, F. & Bahmani, N. (2014). Business failure factors in Iranian SMEs: Do successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs have different viewpoints? Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 4(1), 10.

- Aldrich, H., Zimmer, C. & Jones, T. (1986). Small business still speaks with the same voice: A replication of the voice of small business and the politics of survival. The Sociological Review, 34(2), 335-356.

- Amabile, T.M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview Press: Boulder, CO.

- Anumnu, S.I. (2014). Knowledge management and development of entrepreneurial skills among students in vocational technical institutions in Lagos, Nigeria. Electronic Journal of knowledge Management, 12(2), 144-154.

- Arbuckle, J. (1997). Amos users' guide, version 3.6. Marketing Division, SPSS Incorporated.

- Arranz, N., Ubierna, F., Arroyabe, M.F., Perez, C. & De Arroyabe, J.C. (2017). The effect of curricular and extracurricular activities on university students? entrepreneurial intention and competences. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 1979-2008.

- Backes-Gellner, U. & Werner, A. (2007). Entrepreneurial signalling via education: A success factor in innovative start-ups. Small Business Economics, 29(1-2), 173-190.

- Bagozzi, R.P. & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94.

- Bagozzi, R.P., Baumgartner, J. & Yi, Y. (1989). An investigation into the role of intentions as mediators of the attitude-behaviour relationship. Journal of Economic Psychology, 10(1), 35-62.

- Baldwin, J.R. & Johnson, J. (1998). Innovator typologies, related competencies and performance. Micro Foundations of Economic Growth, 227-253.

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359-373.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman & Co.

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C. & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modelling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2(2), 285-309.

- Baron, R.A. & Markman, G.D. (2003). Beyond social capital: The role of entrepreneurs' social competence in their financial success. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 41-60.

- Baumgartner, H. & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modelling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International journal of Research in Marketing, 13(2), 139-161.

- Baumol, W.J. (1996). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive and destructive. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(1), 3-22.

- Berryman, J. (1983). Small business failure and survey of the literature. European Small Business Journal, 1(4), 47-59.

- Binks, M., Starkey, K. & Mahon, C.L. (2006). Entrepreneurship education and the business school. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 18(1), 1-18.

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442-453.

- Bird, B. (2002). Learning entrepreneurship competencies: The self-directed learning approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 1(2), 203-227.

- Boyatzis, R.E. (1982). The competent manager: A model for effective performance. New York: Wiley.

- Boyd, N.G. & Vozikis, G.S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(4), 63-77.

- Brockhaus, R.H. (1982). The psychology of the entrepreneur, entrepreneurship. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, p. 39-57.

- Byrne, B.M. (2012). A primer of LISREL: Basic applications and programming for confirmatory factor analytic models. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Chandler, G.N. & Hanks, S.H. (1994). Founder competence, the environment and venture performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 77-89.

- Chandler, G.N. & Jansen, E. (1992). The founder's self-assessed competence and venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(3), 223-236.

- Chen, C.C., Greene, P.G. & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295-316.

- Chin, W.W. & Dibbern, J. (2010). Handbook of partial least squares: How to write up and report PLS analyses. New York: Springer, 655-690.

- Cho, S. & Gumeta, H. (2015). Factors affecting university students? start-up intention: Comparative study on Korean and Chinese universities. Journal of Korean Entrepreneurship, 10(3), 150-152.

- Chong, E. (2013). Managerial competencies and career advancement: A comparative study of managers in two countries. Journal of Business Research, 66(3), 345-353.

- Chuang, S.F. (2013). Essential skills for leadership effectiveness in diverse workplace development.

- Çitaku, F., Violato, C., Beran, T., Donnon, T., Hecker, K. & Cawthorpe, D. (2012). Leadership competencies for medical education and healthcare professions: Population-based study. British Medical Journal, 2(2).

- Clayton, G. (1989). Entrepreneurship education at the postsecondary level. Retrieved December, 3, 2005.

- Danhof, C.H. (1949). Observations of entrepreneurship in agriculture. In A. H. Cole (Ed.), Change and the entrepreneur (pp. 20-24). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Davidsson, P. (1995). Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions. Paper presented for the RENT IX Workshop. November 23-24, Piacenza, Italy.

- Dehghanpour, A. (2013). The process of impact of entrepreneurship education and training on entrepreneurship perception and intention: Study of educational system of Iran. Education+ Training, 55(9), 868-885.

- De Noble, A., Jung, D. & Ehrlich, S. (1999). Initiating new ventures: The role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. In Babson Research Conference, Babson College, Boston, MA.

- De Vries, H., Dijkstra, M. & Kuhlman, P. (1988). Self-efficacy: The third factor besides attitude and subjective norm as a predictor of behavioural intentions. Health Education Research, 3(3), 273-282.

- Doll, W.J., Xia, W. & Torkzadeh, G. (1994). A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Quarterly, 453-461.

- Dosi, G. (1982). Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Research Policy, 11(3), 147-162.

- Fayol, H. & Coubrough, J.A. (1930). Industrial and general administration. Paris: Dunod.

- Fayolle, A., Liñán, F. & Moriano, J.A. (2014). Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: Values and motivations in entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(4), 679-689.

- Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Fleming, P. (1996). Entrepreneurship education in Ireland: A longitudinal study. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(1), 94-118.

- Fornell, C. & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 382-388.

- Fritsch, M. (2011). 23 start-ups in innovative industries: Causes and effects. Handbook of Research on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 365-381.

- Fritsch, M. & Aamoucke, R. (2017). Fields of knowledge in higher education institutions and innovative start-ups: An empirical investigation. Papers in Regional Science, 96(S1).

- Garavan, T.N. & O' Cinneide, B. (1994). Entrepreneurship education and training programs: A review and evaluation. Journal of European Industrial Training, 18(8), 3-12.

- Gefen, D., Straub, D. & Boudreau, M.C. (2000). Structural equation modelling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 7.

- GEM 2016/2017-Global Report. (2016/2017). Global entrepreneurship monitor.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. & Anderson, R.E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Harris, A. (1998). Effective teaching: A review of the literature. School Leadership & Management, 18(2), 169-183.

- Hatala, J.P. & Fleming, P.R. (2007). Making transfer climate visible: Utilizing social network analysis to facilitate the transfer of training. Human Resource Development Review, 6(1), 33-63.

- Hessels, J., Van Gelderen, M. & Thurik, R. (2008). Entrepreneurial aspirations, motivations and their drivers. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 323-339.

- Hood, J.N. & Young, J.E. (1993). Entrepreneurship's requisite areas of development: A survey of top executives in successful entrepreneurial firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 115-135.

- Hoogland, J.J. & Boomsma, A. (1998). Robustness studies in covariance structure modelling: An overview and a meta-analysis. Sociological Methods & Research, 26(3), 329-367.

- Huggins, R. (2000). The success and failure of policy-implanted inter-firm network initiatives: Motivations, processes and structure. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 12(2), 111-135.

- Izquierdo, E. & Buelens, M. (2011). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 13(1), 75-91.

- Izquierdo, E., Deschoolmeester, D. & Salazard, D. (2005). The importance of competencies for entrepreneurship, a view from Entrepreneurs and Scholars? perspective.

- Jones, K. (1996). Trust as an affective attitude. Ethics, 107(1), 4-25.

- Jung, D.I., Ehrlich, S.B., De Noble, A.F. & Baik, K.B. (2001). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and its relationship to entrepreneurial action: A comparative study between the US and Korea. Management International, 6(1), 41.

- Katila, R., Rosenberger, J.D. & Eisenhardt, K.M. (2008). Swimming with sharks: Technology ventures, defence mechanisms and corporate relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(2), 295-332.

- Kaur, H. & Bains, A. (2013). Understanding the concept of entrepreneur competency. Journal of Business Management & Social Sciences Research, 2(11), 31-33.

- Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M. & Tornikoski, E.T. (2013). Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Applied Economics, 45(6), 697-707.

- Keyhani, M. & Jafari, M.S. (2008). Islam-friendly entrepreneurship: The Case of Iran. ERENET Profile, 3(4), 34-44.

- Kickul, J., Gundry, L.K., Barbosa, S.D. & Whitcanack, L. (2009). Intuition versus analysis? Testing differential models of cognitive style on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the new venture creation process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 439-453.

- Kim, B. & Cho, S. (2014). Factors affecting university students? start-up intentions: Focus on knowledge and technology based start-up. Journal of Korean Entrepreneurship, 9(4), 86-106.

- Kline, R.B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (Second Edition). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Kolb, D., Lublin, S., Spoth, J. & Baker, R. (1986). Strategic management development: Using experiential learning theory to assess and develop managerial competencies. Journal of Management Development, 5(3), 13-24.

- Kolvereid, L. & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866-885.

- Kristiansen, S. & Indarti, N. (2004). Entrepreneurial intention among Indonesian and Norwegian students. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 12(1), 55-78.

- Kristiansen, S. & Ryen, A. (2002). Enacting their business environments: Asian entrepreneurs in East Africa. African and Asian Studies, 1(3), 165-186.

- Krueger, N.F. (2003). The cognitive psychology of entrepreneurship. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 105-140). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Krueger, N.F. & Brazeal, D.V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 91-104.

- Krueger, N.F. & Carsrud, A.L. (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 5(4), 315-330.

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D. & Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411-432.

- Küttim, M., Kallaste, M., Venesaar, U. & Kiis, A. (2014). Entrepreneurship education at university level and students? entrepreneurial intentions. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 110, 658-668.

- Kyndt, E. & Baert, H. (2015). Entrepreneurial competencies: Assessment and predictive value for entrepreneurship. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 90, 13-25.

- Lee, S.Y., Florida, R. & Acs, Z. (2004). Creativity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of new firm formation. Regional Studies, 38(8), 879-891.

- Lent, R.W. & Hackett, G. (1987). Career self-efficacy: Empirical status and future directions. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 30(3), 347-382.

- Li, L.K. (2012). A study of the attitude, self-efficacy, effort and academic achievement of city U students towards research methods and statistics. Discovery-SS Student E-Journal, 1(54), 154-183.

- Liao, J., Welsch, H. & Tan, W.L. (2005). Venture gestation paths of nascent entrepreneurs: Exploring the temporal patterns. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 16(1), 1-22.

- Liñán, F. & Chen, Y.W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593-617.

- Liñán, F. & Chen, Y.W. (2006). Testing the entrepreneurial intention model on a two-country sample. Working paper. Barcelona, Spain: University of Barcelona.

- Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. & Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. (2005). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels.

- Liñán, F. & Santos, F.J. (2007). Does social capital affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Advances in Economic Research, 13(4), 443-453.

- Lumpkin, G.T., Hills, G. & Shrader, R. (2004). Opportunity recognition. In H.P. Welsch (Ed.) Entrepreneurship: The way ahead (pp. 73-90). New York: Routledge.

- MacBride, E. (2016). Seven reasons Iran could become an entrepreneurial powerhouse. Forbes.

- MacCallum, R.C. & Hong, S. (1997). Power analysis in covariance structure modelling using GFI and AGFI. Multivariate Behavioural Research, 32(2), 193-210.

- Malebana, M.J. (2014). Entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial motivation of South African rural university students. Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies, 6(9), 709-726.

- Malebana, M.J. & Swanepoel, E. (2014). The relationship between exposure to entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Southern African Business Review, 18(1), 1-26.

- Man, T.W., Lau, T. & Chan, K.F. (2002). The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 123-142.

- Markman, G.D. & Baron, R.A. (2003). Person-entrepreneurship fit: Why some people are more successful as entrepreneurs than others. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 281-301.

- Martinez, D., Mora, J.G. & Vila, L.E. (2007). Entrepreneurs, the self-employed and employees among young European higher education graduates. European Journal of Education, 42(1), 99-117.

- McClelland, D.C. (1973). Testing for competence rather than for "intelligence". American Psychologist, 28(1), 1-14.

- McClelland, D.C. & Boyatzis, R.E. (1982). Leadership motive pattern and long-term success in management. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(6), 737.

- McCormick, M.J., Tanguma, J. & López-Forment, A.S. (2002). Extending self-efficacy theory to leadership: A review and empirical test. Journal of Leadership Education, 1(2), 34-49.

- Mueller, S. (2011). Increasing entrepreneurial intention: Effective entrepreneurship course characteristics. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 13(1), 55-74.

- Naktiyok, A., Karabey, C.N. & Gulluce, A.C. (2010). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The Turkish case. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(4), 419-435.

- Nerkar, A. & Roberts, P.W. (2004). Technological and product-market experience and the success of new product introductions in the pharmaceutical industry. Strategic Management Journal, 25(9), 779-799.

- Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric Theory (Second Edition). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Othman, N.H. & Ishak, S.B. (2009). Attitude towards choosing a career in entrepreneurship amongst graduates. European Journal of Social Sciences, 10(3), 419-434.

- Othman, N., Hashim, N. & Ab Wahid, H. (2012). Readiness towards entrepreneurship education: Students and Malaysian universities. Education+Training, 54(9), 697-708.

- Pihie, Z.A.L. & Akmaliah, Z. (2009). Entrepreneurship as a career choice: An analysis of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention of university students. European Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 338-349.

- Piperopoulos, P. & Dimov, D. (2015). Burst bubbles or build steam? Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 970-985.

- Pitt, M. & Clarke, K. (1999). Competing on competence: A knowledge perspective on the management of strategic innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 11(3), 301-316.

- Ramayah, T. & Harun, Z. (2005). Entrepreneurial Intention among the Students of USM. International Journal of Management and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8-20.

- Reynolds, P., Bosma, N.S., Autio, E., Hunt, S., De Bono, N., Servais, I. & Chin, N. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998-2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205-231.

- Rezaei, S., Dana, L.P. & Ramadani, V. (2017). Introduction to Iranian Entrepreneurship. In Iranian Entrepreneurship (pp. 1-11). Springer, Cham.

- Robinson, P.B., Stimpson, D.V., Huefner, J.C. & Hunt, H.K. (1991). An attitude approach to the prediction of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 15(4), 13-31.

- Ronstadt, R. (1985). Every entrepreneur's nightmare: The decision to become an ex-entrepreneur and work for someone else. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 409-434.

- Sánchez, J.C. (2011). University training for entrepreneurial competencies: Its impact on intention of venture creation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 239-254.

- Schreiber, J.B., Nora, A., Stage, F.K., Barlow, E. A. & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modelling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323-338.

- Scott, M.G. & Twomey, D.G. (1988). The long-term supply of entrepreneurs: Students' career aspirations in relation to entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 26(4), 5-13.

- Shane, S.A. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Shapero, A. & Sokol, L. (1982). Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C. Kent, D. Sexton & K. Vesper (Eds.), The encyclopaedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72-90). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O. & Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention-behaviour link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4), 386-399.

- Solesvik, M.Z., Westhead, P., Kolvereid, L. & Matlay, H. (2012). Student intentions to become self-employed: The Ukrainian context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 441-460.

- Stam, E. & van Stel, A. (2011). Types of entrepreneurship and economic growth. Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Economic Development, 78-95.

- Sternberg, R.J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK.

- Steinberg, R. (2005). Entrepreneurship in German regions and the policy dimension-empirical evidence from the regional entrepreneurship monitor (REM). In Local Heroes in the Global Village (pp. 113-144). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Sullivan, D.M. & Ford, C.M. (2014). How entrepreneurs use networks to address changing resource requirements during early venture development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 551-574.

- Teece, D.J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2), 172-194.

- Thompson, E.R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669-694.

- Trivedi, R. (2016). Does university play significant role in shaping entrepreneurial intention? A cross-country comparative analysis. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(3), 790-811.

- Tsai, K.H., Chang, H.C. & Peng, C.Y. (2016). Extending the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: A moderated mediation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 445-463.

- Van Gelderen, M., Brand, M., van Praag, M., Bodewes, W., Poutsma, E. & Van Gils, A. (2008). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions by means of the theory of planned behaviour. Career Development International, 13(6), 538-559.

- Veciana, J.M., Aponte, M. & Urbano, D. (2005). University students? attitudes towards entrepreneurship: A two countries comparison. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(2), 165-182.

- Volery, T., Mueller, S. & von Siemens, B. (2015). Entrepreneur ambidexterity: A study of entrepreneur behaviours and competencies in growth-oriented small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 33(2), 109-129.

- Vroom, V.H. & Jago, A.G. (2007). The role of the situation in leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 17.

- Wagener, S., Gorgievski, M. & Rijsdijk, S. (2010). Businessman or host? Individual differences between entrepreneurs and small business owners in the hospitality industry. The Service Industries Journal, 30(9), 1513-1527.

- Ward, T.B. (2004). Cognition, creativity and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 173-188.

- Whiddett, S. & Hollyforde, S. (2003). A practical guide to competencies: How to enhance individual and organizational performance. London: CIPD Publishing.

- Wiklund, J. & Shepherd, D. (2003). Aspiring for and achieving growth: The moderating role of resources and opportunities. Journal of Management Studies, 40(8), 1919-1941.

- Wu, L.Y. (2007). Entrepreneurial resources, dynamic capabilities and start-up performance of Taiwan's high-tech firms. Journal of Business Research, 60(5), 549-555.

- Zaccaro, S.J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6-16.

- Zarefard, M. & Cho, S.E., (2017). Relationship between entrepreneurs? managerial competencies and innovative start-up intentions in university students: An Iranian case. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 21(3).

- Zhang, Y., Duysters, G. & Cloodt, M. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students? entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(3), 623-641.

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S.E. & Hills, G.E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265.