Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 4

Entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia: Risk Attitude and Predisposition towards Risk Management

Ali Murad Syed, College of Business Administration, Imam Abdul-Rahman Bin Faisal University

Adel Alaraifi, College of Business Administration, Imam Abdul-Rahman Bin Faisal University

Shabir Ahmad, College of Business Administration, Imam Abdul-Rahman Bin Faisal University

Abstract

The success and survival of startup companies depend on the decision making of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs are individuals who are considered as risk takers. Recent academic literature supports a positive relationship between the decision to become an entrepreneur and their attitude towards risk taking. In the literature, entrepreneurs are also considered as a homogeneous group having a similar risk attitude. In this paper, we investigate the important characteristics of Saudi entrepreneurs with respect to risk perception and financial risk tolerance. We collected data from 132 entrepreneurs and analyzed it using Partial Least Square approach of Structural Equation Modeling. We found that entrepreneurs’ perception towards risk has a positive significant influence on financial risk tolerance, risk propensity, and entrepreneurial openness. In addition, findings of this study have shown that the relationship between entrepreneurs’ perception and financial risk tolerance is partially mediated by entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity. The study contributes to the body of knowledge by being a pioneer in examining the relationship between risk perception and financial risk tolerance in the specific context of Saudi Arabia.

Keywords

Risk Attitude, Risk Propensity, Categorization Theory, Decision Theory, Entrepreneurship Openness, Financial Risk Tolerance.

Introduction

In today’s world, there is a strong demand to bring new and innovative ideas, products and services to the market. At the same time, startup companies or firms have more chances of failure and researchers have discussed various reasons for that. Entrepreneurs are individuals who are motivated and ready to take risks in their lives. Utmost importance should be given to the investigation of personal and knowledge preconditions of persons who are having their own businesses. Entrepreneurs, driven by vision, innovation, and impulse, often look at broader things and fail to focus on the micro details. With such propensities, they ignore potential threats and risks but may add to the impending problems. Mostly they are not equipped to manage the rapid business environmental changes. Sometimes their behavior may prove to be counterproductive. And finally, a poorly conceived business decision is sufficient to take the enterprise down the road. Risk management is one of the most important considerations for entrepreneurs. Risk management is something that new entrepreneurs need to become familiar with if they want their businesses to survive. Risk is a subset of entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurs should be unsurpassed risk managers. The hoax is to create maximum opportunities with a proper balance between risk and the reward. Mills & Pawson (2012) confirmed that risk-taking is a critical variable for understanding enterprising behavior and the cornerstone of any decision to start a business.

Risk relates to the difficulty of predicting future outcomes and risk perception is observed as a form of intentional, analytic information processing over some time period. It is also dependent on innate and out of box thinking guided by emotive and affective processes. There is a relationship between perceived risk and supposed benefits and entrepreneurial choice that highlights the role of risk aversion in the previous researches.

Brandstätter (1997); Rauch & Frese (2007); Zhao & Seibert (2006) showed the relationship of personality traits of entrepreneurs with entrepreneurial status, creation, and success of the business. Entrepreneurial openness is one of the personality traits which has a positive relationship with the firm performance and growth of the company. Zhao & Seibert (2006) showed that entrepreneurs have higher scores on openness as compared to the managers. Slavec & Proceedings (2014) found the relationship between entrepreneurial openness, goals of the firm and firm performance and proved that entrepreneurial openness has a positive impact on firm performance. Rasmussen & Clausen (2012) examined the role of openness for science-based entrepreneurial firms (SBEF) to be innovative and found a positive correlation between them. Gomezel & Rangus (2018) argued that creative innovation is connected to entrepreneurship and found that open innovation attitude at the individual level positively affects entrepreneurial alertness. Authors also showed that financial performance is improved by entrepreneurial alertness whereas Wang et al. (2016) failed to establish the effect of emotional stability and openness on risk propensity for Chinese Construction managers.

The concept of entrepreneurship is gaining popularity in Saudi Arabia and various universities have established on-campus entrepreneurship centers and graduates are more attracted towards starting their own businesses instead of doing jobs. Young Saudi generation graduating from business schools who want to become an entrepreneur is increasing at a tremendous rate. Saudi Government is also promoting entrepreneurship activities under vision 2030 to diversify its economy. There are various government institutions mandated to directly support startup activity in the country. The Saudi government is financing the universities, nonprofit organizations, and economic cities, and signing partnerships with companies to further drive entrepreneurship support.

Entrepreneurs are also new in establishing relationships among various risks that can create severe problems for their new firms. In this regard, seminal work is carried out by Stinchcombe & March (1965) who proposed that more tendency to fail because firms have not established effective work roles and relationships. In this paper, we will focus on perception towards risk management, risk propensity; entrepreneurship and the financial risk tolerance by the entrepreneurs of Saudi Arabia are important variables to study for the success or failure of any startups. Underlying problems due to various risks facing by new firms/startups and the attitude of entrepreneurs are essential to study. Startups vary considerably in their access to resources and entrepreneurs are new to risk management techniques which ultimately increase their chances of failure.

It is important to develop risk tolerance differences at the individual level as the individuals widely diverge in financial risk level that they are ready to take. The assessment of financial risk tolerance as an attitudinal input into the financial decision-making process is considered very important. Liles (1974) proposed that if a person becomes an entrepreneur, he/she jeopardies his financial well-being, family relations, and psychic well-being. The entrepreneur devotes him/herself to the venture at a personal level and the success/failure of the venture has emotional consequences and affects his/her personal life. So, the entrepreneur should investigate the risks associated with the business proposal in a very careful way.

The study makes major contributions to entrepreneurship research. First, it determines the direct role of risk perception, entrepreneurial openness, and risk-taking propensity on financial risk tolerance. Secondly, it examines the mediating role of entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity between risk perception and financial risk tolerance. It is important to measure the mediating roles of entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity for Saudi entrepreneurs as their corporate culture is dominated by local social and cultural factors (Falgi, 2009). As per the author’s opinion, the impact of these risk variables has not been empirically examined before on Saudi entrepreneurs.

Literature Review

Kihlstrom and Laffont (1979) used an entrepreneurial model and developed a theory of competitive equilibrium under uncertain conditions. According to this theory, workers are more risk-averse individuals and entrepreneurs are less risk-averse individuals. As per this theory, larger firms were run by less risk-averse entrepreneurs and the equilibrium wage was reduced by economy-wide increases in risk aversion. Authors based their theory on the work of Knight (1921). Some economic researchers and psychologists argued that the general population is less risk tolerant than entrepreneurs while some psychologists believes that entrepreneurs don’t differ than non-entrepreneurial managers in their disposition towards risk. (Block et al., 2015) argued that there are different types of entrepreneurs in terms of risk taking and they showed that opportunity entrepreneurs are more willing to take risks than necessity entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs behave differently from managers by their heuristic in decision making (Busenitz & Barney, 1997) and the difference is substantial. Risk management for entrepreneurs has received increased attention over the past few years as this will influence their financial performance and the future of the firm to a large extent. Belás et al. (2015) argued that in the SME segment of the Czech Republic, a comparatively smaller number of entrepreneurs keep financial reserves in their companies. Kozubíková et al. (2015) discovered the relationship among personality characteristics and perception and management of business risks approach for the Czech Republic and Slovakia by dividing the entrepreneurs into two categories: artist-entrepreneurs and businessmen-la-borers. Authors found that market risk is rated as the most important risk for both groups and also found a significant difference in their approach towards credit risk. Comparison of risk preference by entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs of Indonesia was done by Sohn (2017) and he argued that entrepreneurs were risk-tolerant workers as compared to risk-averse workers and they constitute more than 20 percent of entrepreneurs’ proportion in the labor force.

Starting a new business is one of the most important decisions an individual can make. Previous studies have confirmed that individual factors like motivation, confidence and perception of risk have the highest impact on the complex decision to start new businesses (Arenius & Minniti, 2005). The authors argued that perceptual variables are significantly correlated with new business creation. Risk perception concerns how individuals assess the risk innate to a particular situation (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992) and is a subjective issue. Different entrepreneurs may assess the same risk situation differently and respond differently.

Entrepreneurs are considered to be risk takers if we compare them with the managers and the general population. Entrepreneurs have to set goals and are willing to take on reasonable risks.

Personal characteristics of entrepreneurs also play an important part in the risk taking decisions. Sidik (2012) mentioned that the entrepreneurs tend to manage their business by using their strong and specific qualities. Kozubíková et al. (2015) examined the relationship between personality characteristics and approach to the perception and management of business risks. The authors evaluated the ability of the entrepreneurs to manage the financial risk and showed a high degree of confidence of individual groups of entrepreneurs. Hvide & Panos (2014) argued that more risk tolerant individuals are more likely to become entrepreneurs but perform worse. On the other hand some studies suggested that personality traits are not strongly enough related to entrepreneurship to warrant further studies (Baum et al., 2014). Psychological studies of entrepreneurs have shown that personality characteristic is their ability to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty (Alvarez & Barney, 2005; Holm et al., 2013). Cultural differences among the entrepreneurs are also important to study. Liu & Almor (2016) argued that cultural influences are critical in determining how entrepreneurs perceive, analyze and deal with uncertainty in inter-organizational situations.

Initial studies suggested that more risk tolerant individuals are more likely to become entrepreneurs, but perform worse (Knight, 1921) and Hvide & Panos (2014) also confirmed that more risk tolerant individuals are more likely to start their firms.

Initial study by Brockhaus Sr (1980) suggested that risk taking propensity was not a distinguishing characteristic of entrepreneurs. (Masters & Meier, 1988) argued that entrepreneurs and managers do not differ in risk taking propensity. (Stewart Jr & Roth, 2004) discussed the two competing theoretical positions regarding the effects of risk-taking propensity on entrepreneurship and success. The first position hypothesizes that entrepreneurs have a higher risk-taking propensity than other people (Knight, 1921) while the second position suggested a curvilinear relationship between risk-taking and entrepreneurship (Meyer et al., 1961).

In this study we are going to find the relation between risk perception, entrepreneurship openness (personality trait), risk taking propensity and the risk tolerance of the entrepreneurs. Our research question would be “what is the relation between risk perception and financial risk tolerance with and without mediating effect of entrepreneurship openness and risk-taking propensity?’

As per the author’s opinion, the relation among these risk variables has not been empirically examined before on Saudi entrepreneurs. Our contribution to the literature will be multiple folds. First, this study will determine the impact of risk perception on the behavior of Saudi entrepreneurs. Secondly, the mediating role of personality trait (Openness) and risk propensity will be observed on risk tolerance of Saudi Entrepreneurs. The social implication of this study will also be very important as entrepreneurship is widely encouraged by the Saudi government and success or failure of new startups depends on the risk behavior of the entrepreneurs. This study will help the policymakers to devise new strategies based on the results of this study to reduce the failure of new startups.

Theoretical Framework

The variables used in the study are conceptualized in the following subsections prior to hypotheses development.

Risk Perception

An assessment of risk inheritance in any situation by a decision-maker may be called as risk perception. It is defined as the decision maker's labeling of various circumstances (S. E. Jackson & Dutton, 1988; Patrick et al., 1985). As per prospect theory, the risk-averse condition is led by positively framed situations and risk-taking is led by negatively framed condition (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). Sitkin & Pablo (1992) suggested that perceived risk and making risky decisions have a negative relationship between them. Various dimensions of risk perception have been mentioned in previous studies, the most important dimensions with their definitions are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Dimensions of Risk Perception | ||

| Dimension | Definition | Previous Researches |

| Social risk | It is affiliated with a potential loss of prestige or social recognition in case of failure in forming a business |

Hisrich (1998), Harvard Schaper & Volery (2004) |

| Time Risk | This type of risk is affiliated with the potential difficulty to meet other individual and professional responsibilities. | Harvard Schaper & Volery (2004); Vasumathi et al. (2003) |

| Health Risk | It is affiliated with the potential damage in the physical and psychological health, due to the effort required by a business | Harvard Schaper & Volery (2004); Hisrich (1998); Vasumathi et al. (2003) |

| Personal Risk | It is affiliated with the potential negative impact on the individual’s personal development required by a business. | Barbosa, et al. (2007b) |

Entrepreneurial Openness

Personal cognitive strength at the individual level is known as openness and one of the Big-5 factor personality model traits. For entrepreneurs, openness is acknowledged as important personality strength as it adds something new to what they already know. Openness is about learning, to search for novelty, to receive customer feedback, gathering information and suggestions from different sources. Busenitz & Arthurs (2014) describe open entrepreneurs as effective learners while Rauch & Frese (2007) mention that entrepreneurs seek feedback while comparing the attractiveness and feasibility of the opportunities.

Risk Propensity

Perceived chances or probability of receiving the rewards linked with the success of a planned condition is known as risk propensity (Brockhaus Sr, 1980). An individual's risk-taking propensities or measure of willingness to take risks has been conceptualized as risk propensity (Baird & Thomas, 1985; Fischhoff et al., 1983). Also, risk propensity is defined by Sitkin & Weingart (1995) as a person’s existing predisposition to take or avoid risks. It can be conceptualized as a personality trait that can change over time. Sitkin & Pablo (1992) argued that risk propensity is the major factor of risk behavior which can be learned or inherited.

Financial Risk Tolerance

An attitudinal input into the financial decision-making process may be called a financial risk tolerance assessment. Financial risk tolerance is considered as a financial concept which is measured by the attitude towards risk. Hall & Woodward (2010) argue that entrepreneurs have comparatively high-risk tolerance while entrepreneurs are more risk-averse than common man (Xu & Ruef, 2004). Corter & Chen (2006) confirmed that financial risk tolerance reliably predicts financial behavior.

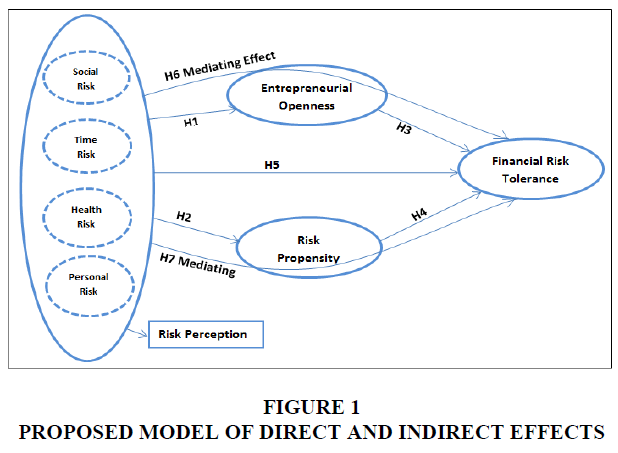

In most of the studies about decision-making behavior, the focus was on direct effects of risk behavior determinants in organizational situations. In our opinion, risk behavior reflection by a complex set of factors does not seem to be sufficient. Therefore, we proposed the mediatory roles of entrepreneurial openness and risk propensity between entrepreneur’s perceptions and financial risk tolerance. Figure 1 shows the basic idea underlying the mediation model of financial risk tolerance determinants and captures the most critical variables. First, it represents the characteristics affecting financial risk tolerance through direct effects of risk perception, risk-taking propensity, and entrepreneurial openness and then the indirect effects through mediating variables (entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity). The paths shown in Figure 1 are keyed to the hypothesized relationship between the variables of the model. In the proposed model, risk perception, entrepreneurial openness and risk propensity serve as independent variables whereas financial risk tolerance is taken as the dependent variable. In addition, entrepreneurial openness and risk propensity have been taken as mediators between risk perception and financial risk tolerance.

As per common perception, the corporate world has branded entrepreneurs as risk-takers which may not be exactly true. There is a possibility that the characteristics reported in the entrepreneurship literature are actually the result of systematic differences in cognitive processes instead of risk-taking. The risk to be considered as a variation function in the distribution of possible outcomes, the likelihood of outcomes and their subjective values as per classic decision theory risk (March & Shapira, 1987). Decision theory provides a basis for making rational decisions under various risk and uncertainty scenarios. It is normative in intent and concerned with the line of action that will be directed to the decision-makers objectives with the expectations and their values. Some researchers argued that risk decisions are not based solely on rational calculations but are also affected by an individual predisposition towards risk (Bromiley & Curley, 1992; Jackso et al., 1972; Plax & Rosenfeld, 1976). Rather than risk-taking, the characteristics are in fact the outcome of systematic differences in cognitive processes.

As per categorization theory of cognition, while doing their business situations assessments entrepreneurs are considered as more optimistic (Cooper et al., 1988). The theory recognizes the power of cognitive heuristics to clarify behavior and decision-making by the people (Mervis & Rosch, 1981; Rosch et al., 1976). This theory also gives rational of categorization of situations by the entrepreneurs as the holding strengths and opportunities because the positive features of a situation are more striking for them. Plax & Rosenfeld (1976) argue that entrepreneurs are not more predisposed to take risk than non-entrepreneurs and they have the same risk propensity. Categorization theory accepts the power of cognitive heuristics which is needed to clarify the decision-making. As per this theory, people make use of cognitive strategies to manage complex indications as it is beyond their cognitive capacity to process and remember all information stimuli.

Thus, based on the preceding discussion we forward seven hypotheses that represent the beliefs and attitude of entrepreneurs towards risk management and preferences. Among them, two hypotheses (H6 and H7) examine the mediating role of entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity, respectively. The seven hypotheses include:

H1(Null): Risk perception has significant positive influence on entrepreneurship openness.

H2(Null): Risk perception has significant positive influence on risk taking propensity.

H3(Null): Entrepreneurial openness has significant positive influence on financial risk tolerance.

H4(Null): Risk propensity has significant positive influence on financial risk tolerance.

H5(Null): Risk perception has significant positive influence on financial risk tolerance.

H6(Null): Risk perception has significant positive influence on financial risk tolerance when mediated by entrepreneurial openness.

H7(Null): Risk perception has significant positive influence on financial risk tolerance when mediated by risk taking propensity.

Data and Methodology

This study adopts a positivist research paradigm that entails a quantitative research method. We collected data using a survey questionnaire from the leading entrepreneurs of Saudi Arabia. This required us the development and distribution of a large-scale survey covering Saudi entrepreneurs. To ensure validity and reliability of the data, questionnaire development and sampling are the important elements in empirical research. We adopt eight steps process introduced by DeVellis (2003) to develop the survey questionnaire. The variables of the hypothesized model are measured with a multi-item scale. The risk perception is having four dimensions namely, social risk, time risk, health risk, and personal risk. Before finalizing the research instrument, face validity was established by showing the questionnaire to three faculty members of management/entrepreneurship discipline to improve the clarity of the research instruments and relevance of the items (Cronbach, 1971; DeVellis, 2003). Following the validation and revision of the instrument, the final version of the questionnaire was sent to 623 entrepreneurs. The convenience sampling was done for our respondents from the leading entrepreneurs of Saudi Arabia.

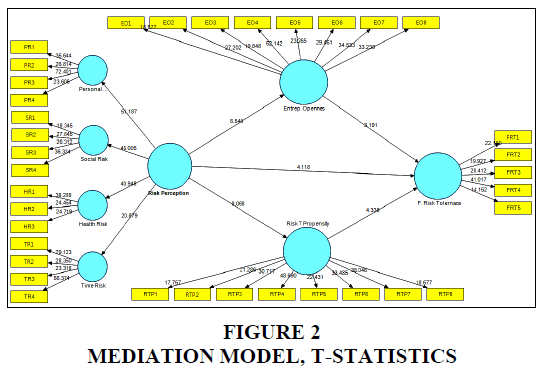

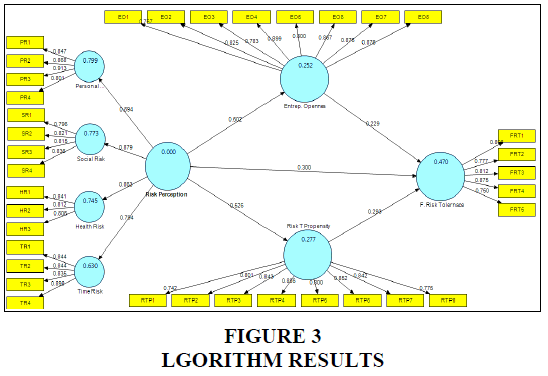

In order to test the research model and hypotheses, we used the SmartPLS 3.2.8 tool of Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) approach. PLS-SEM has been extensively used in management and innovation research (Jöreskog & Wold, 1982; Lohmöller, 1989). PLS is a second-generation modeling technique that helps to evaluate the quality of construct measurement as well as interrelationships among the constructs (Fornell & Bookstein, 1982). The features of PLS make it suitable for both theoretical model development and testing (Bontis & Fitz-Enz, 2002; Fornell & Bookstein, 1982). Assessment of research model in PLS is performed in two separate stages (Chin, 1998; Gefen & Straub, 2005). Prior to structural/path model assessment, it is mandatory to ensure the validity and reliability of measurement (outer) model. We established the reliability of the measurement model through higher indicators loadings and composite reliability scores. The validity was ensured through convergent and discriminant validity tests. Once measurement model was validated, the structural (inner) model was assessed for testing hypotheses through path coefficients (β) and for the explanatory power (R2) (Henseler et al., 2009). As one of the constructs namely risk perception is a second-order construct in our model, we established the validity and reliability for second-order construct prior to the assessment of the structural model (inner model).

Analysis and Findings

The final version of the questionnaire was sent to 623 entrepreneurs based on convenience sampling. After data screening and filtering procedures, 132 responses were used in final data analysis that corresponds to a response rate of 21.1%.

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic profile of the Saudi entrepreneur's sample used in this research. Table 2 shows that 56% of our respondents are males while 44% of respondents are females. The table shows that females are working as entrepreneurs and their percentage is not less.

| Table 2 Gender of Respondents | ||

| Gender | Count | Percentage |

| Male | 78 | 59 |

| Female | 54 | 41 |

| Total | 132 | 100 |

Table 3 shows that 8.3% of respondents are having an age 18-24 years while 11.4% of respondents have an age of 25-34 years. 40.9% have an age of 35-44 years while 27.3% have an age more than 25-54 years and 12.1% having age more than 54 years.

| Table 3 Age of Respondents | ||

| Age (Years) | Count | Percentage |

| 18-24 | 11 | 8.3 |

| 25-34 | 15 | 11.4 |

| 35-44 | 54 | 40.9 |

| 45-54 | 36 | 27.3 |

| More than 54 | 16 | 12.1 |

| Total | 132 | 100 |

Table 4 shows the academic qualification of the respondents. The table shows that 57.6% of our respondents have a bachelor’s degree while 26.5% have master’s degree.

| Table 4 Qualification of RESPONDENTS | ||

| Qualification | Count | Percentage |

| No degree | 0 | 0 |

| High school diploma | 8 | 6.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 76 | 57.6 |

| Master’s degree | 35 | 26.5 |

| PhD degree | 13 | 9.8 |

| Total | 132 | 100 |

Table 5 shows 61.4% of the respondents have a degree in business or have taken any entrepreneurship course in their academic career while 38.6% have not studied business or entrepreneurship course in their career. This also highlights the importance of entrepreneurship as a course/degree for the people who wants to start their own successful business.

| Table 5 Business Degree or Entrepreneurship Course of Respondents | ||

| Business Degree or any Entrepreneurship Course | Count | Percentage |

| Yes | 81 | 61.4 |

| No | 51 | 38.6 |

Assessment of Measurement Model

The validity and reliability of the structural model primarily depend upon valid and reliable measurement models. It is, therefore, mandatory to examine the properties of the measurement models prior to analyzing the structural model. As shown in Table 6, the reliability of the measurement model was established through higher factor loadings of indicators to respective latent variables (above 0.70). The items which did not fulfill this criterion were excluded from the analysis. Relatively higher (CR> 0.86) scores of composite reliability for each latent variable (Table 6) further strengthen the reliability of the measurement model. The model fulfilled all three convergent validity criteria as well:

| Table 6 Reliability and Convergent Validity of Measurement Model | ||||

| Constructs & Indicators | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | |

| Entrepreneurial Openness | 0.949 | 0.702 | ||

| EO1 | I learn new marketing approaches | 0.767 | ||

| EO2 | I learn new approaches about managing the business | 0.825 | ||

| EO3 | I look for ideas for new products or services | 0.783 | ||

| EO4 | I look for new markets | 0.899 | ||

| EO5 | I carefully examine all changes proposed to me by others (for example, I search for additional information on how to introduce changes, etc.) | 0.800 | ||

| EO6 | I ask employees for their opinion on which improvements could be introduced | 0.867 | ||

| EO7 | In terms of business matters, I have an open mind (thinking out of the box and evaluating all options) | 0.876 | ||

| EO8 | In business, I search for creative solutions | 0.876 | ||

| Financial Risk Tolerance | 0.902 | 0.649 | ||

| FRT1 | Given the best and worst case returns of the four investment choices below, which would you prefer? a)$200 gain best case; $0 gain/loss worst case, b)$800 gain best case; $200 loss worst case, c) $2,600 gain best case; $800 loss worst case, d) $4,800 gain best case; $2,400 loss worst case | 0.808 | ||

| FRT2 | If you had to invest $20,000, which of the following investment choices would you find most appealing? a) 60% in low-risk investments, 30% in medium-risk investments, 10% in high-risk investments, b) 30% in low-risk investments, 40% in medium-risk investments, 30% in high-risk investments, c) 10% in low-risk investments, 40% in medium-risk investments, 50% in high-risk investments | 0.777 | ||

| FRT3 | In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $2,000. You are now asked to choose between: a) A sure loss of $500, b) A 50% chance to lose $1,000 and a 50% chance to lose nothing | 0.812 | ||

| FRT4 | You are on a TV game show and can choose one of the following. Which would you take? a) $1,000 in cash,, b) A 50% chance at winning $5,000, c) A 25% chance at winning $10,000, d) A 5% chance at winning $100,000 | 0.875 | ||

| FRT5 | In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $1,000. You are now asked to choose between: a) A sure gain of $500, b) A 50% chance to gain $1,000 and a 50% chance to gain nothing | 0.750 | ||

| Risk Taking Propensity | 0.942 | 0.670 | ||

| RTP1 | I have confidence on my ability to recover from my mistakes no matter how big | 0.742 | ||

| RTP2 | I tolerate ambiguity and unpredictability well | 0.801 | ||

| RTP3 | I would promote someone with unlimited potential but limited experience to a key position over someone with limited potential but more experience. | 0.843 | ||

| RTP4 | Anything worth doing is worth doing less than perfectly | 0.886 | ||

| RTP5 | Taking business risks makes good sense only in the absence of acceptable alternatives | 0.800 | ||

| RTP6 | I would rather feel intense disappointment than intense regret. | 0.852 | ||

| RTP7 | I believe that opportunity generally knocks only once | 0.842 | ||

| RTP8 | When facing a decision with uncertain consequences, my potential losses are my greatest concern. | 0.775 | ||

| Health Risk | 0.860 | 0.673 | ||

| HR1 | Starting your own business can negatively affect your health | 0.841 | ||

| HR2 | Starting your own business can be very stressful | 0.812 | ||

| HR3 | Starting your own business can put your physical wellbeing at risk | 0.806 | ||

| Personal Risk | 0.918 | 0.736 | ||

| PR1 | Failing in the creation of your own business would negatively affect your professional career | 0.847 | ||

| PR2 | Your self-esteem would be significantly affected if you failed in creating your own business | 0.868 | ||

| PR3 | Failing in the creation of your own business would have a very negative effect on your confidence to take on new projects | 0.913 | ||

| PR4 | Starting your own business would negatively affect your personal life | 0.801 | ||

| Social Risk | 0.889 | 0.668 | ||

| SR1 | It’s very likely for you to lose the respect of people who are important to you is your fail in creating your own business | 0.796 | ||

| SR2 | Failing in the creation of your own business can have a negative impact in the way in which your friends and family see you | 0.821 | ||

| SR3 | If you fail in creating your own business, your social life can be affected negatively | 0.815 | ||

| SR4 | Failing in the creation of your own business can have negative consequences in your relationships with people you value | 0.836 | ||

| Time Risk | 0.916 | 0.732 | ||

| TR1 | Starting your own business means renouncing other professional opportunities in your career | 0.844 | ||

| TR2 | Starting your own business reduced the time you could dedicate to other activities that are important to you | 0.844 | ||

| TR3 | Starting your own business requires investing too much time | 0.835 | ||

| TR4 | Starting your own business could jeopardize your personal and professional development | 0.898 | ||

1. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values are greater than 0.5.

2. CR values are greater than 0.7.

3. All CR values are greater than corresponding AVE values (Hair et al., 2017).

The discriminant validity of the measurement model was ensured through Fornell and Larker criterion. According to Fornell & Larcker (1981) criterion, the discriminant validity is determined by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with squared correlation coefficients between each pair of the factors. As shown in Table 7, all the square root of AVE values along the diagonal are higher than the corresponding squared correlation coefficients of the latent variables.

| Table 7 Discriminant Validly of Measurement Model | |||||||

| Entrepreneurial Openness | 0.838 | ||||||

| Financial Risk Tolerance | 0.554 | 0.806 | |||||

| Health Risk | 0.490 | 0.587 | 0.820 | ||||

| Personal Risk | 0.375 | 0.587 | 0.773 | 0.858 | |||

| Risk Taking Propensity | 0.595 | 0.587 | 0.561 | 0.459 | 0.819 | ||

| Social Risk | 0.534 | 0.496 | 0.699 | 0.684 | 0.45 | 0.817 | |

| Time Risk | 0.335 | 0.280 | 0.532 | 0.580 | 0.349 | 0.623 | 0.856 |

| *The bold shaded values along the diagonal are the square root of AVE and indicate the highest in the respective column and row. | |||||||

Assessment of Second Order Construct

Risk perception in the proposed research model has been taken as a second-order construct with four dimensions, namely social risk, time risk, health risk, and personal risk (see Table 1). Each latent variable is measured through respective indicators. Table 8 shows the results of the convergent validity and reliability of the second-order construct.

| Table 8 Validity and Reliability of Second Order Construct | ||||

| Constructs & Indicators | Loading | T-value | CR | AVE |

| Risk Perception | 0.941 | 0.517 | ||

| Health Risk | 0.863 | 39.189 | ||

| Personal Risk | 0.894 | 50.32 | ||

| Social Risk | 0.879 | 45.069 | ||

| Time Risk | 0.794 | 21.337 | ||

| Note: Critical t-value **=1.96 (P<0.05) | ||||

Following a similar criterion, the factor loadings of latent variables were higher than 0.7 thresholds, ranging between 0.794 and 0.863. The composite reliability value of 0.941shows the reliability of the scale. The AVE value 0.517 establishes the convergent validity of the construct. Table 9 indicates that the discriminant validity criterion is also fulfilled. Thus, the results confirmed the validity and reliability of the second-order construct.

| Table 9 Discriminant Validity of 2nd Order Construct Through Fornell and Larcker Criterion | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Openness | Financial Risk Tolerance | Risk Perception | Risk Taking Propensity | |

| Entrepreneurial Openness | 0.838 | |||

| Financial Risk Tolerance | 0.554 | 0.806 | ||

| Risk Perception | 0.502 | 0.569 | 0.819 | |

| Risk Taking Propensity | 0.595 | 0.587 | 0.526 | 0.719 |

| *The bold shaded values along the diagonal are the square root of AVE and indicate the highest in the respective column and row. | ||||

Assessment of Structural Model

Once the validity and reliability of the measurement model were established, the structural model was assessed for hypotheses and model testing. The coefficient of determination and path coefficients were used to assess the explanatory power of the model and the significance and relevance of the hypothesized relationships between studies constructs. Coefficient of determination (R2) is the most widely used approach to assess the explanatory power of the structural model in PLS that measures the predictive accuracy of the model by calculating squared correlations between the actual and predicted values of the endogenous construct and it represents the combined effect of exogenous latent variables on an endogenous latent variable in multiple regression (Hair et al., 2017). Whereas, the path coefficients (β) indicates the direct effect of a variable assumed to be a cause on another variable assumed to be an effect (Chin, 1998; Henseler et al., 2009). According to Chin (1998), an R2 value of 0.67 is considered to have substantial explanatory power whereas values of 0.33 and 0.19 are considered to have respectively moderate and weak value power.

The findings show (Table 10) that all three endogenous constructs are having statistically significant R2 values with their corresponding exogenous constructs. The R2 value of financial risk tolerance construct is 0.47 which is predicted by entrepreneurship openness, risk propensity, and risk perception. On the other hand, risk perception explains 25% (R2=0.252) of entrepreneurial openness and 28 percent of (R2=0.277) of risk propensity. These results confirm that our model has a moderate range of explanatory power for each construct.

| Table 10 Explanatory Power of the Model | ||||

| Endogenous Constructs | R2 | T-Value | P-Value | Corresponding Exogenous Constructs |

| Financial Risk Tolerance | 0.47 | 6.930** | 0 | 1. Entrepreneurial Openness 2. Risk Taking Propensity 3. Risk Perception |

| Entrepreneurial Openness | 0.252 | 4.425** | 0 | Risk Perception |

| Risk Taking Propensity | 0.277 | 4.161** | 0 | Risk Perception |

| Note: **Critical t-value 1.96 (P<0.05) | ||||

The structural path coefficients empirically endorse the theoretical assumptions about the relationships among the model’s latent constructs (Henseler et al., 2009). The algebraic sign of path coefficients are aligned with theoretical assumptions and statistical significance is verified to find the strong or weak relationship among constructs (Barclay et al., 1995; Tenenhaus et al., 1995). Table 11 shows the results of our structural model with direct and indirect effects. The indirect effects were analyzed using two mediators, entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity. The results show that both direct and indirect relationships were statistically significant indicating that all seven hypotheses were supported. Table 11 shows path coefficients with statistically significant t and p-values, indicating support for all the hypotheses of the proposed model.

| Table 11 Results of the Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing | ||||||

| Hypothesis | β | T-value | P-value | Decision | ||

| H1 | Risk Perception → Entrepreneurial Openness | 0.502 | 8.825** | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H2 | Entrepreneurial Openness → Financial Risk Taking | 0.229 | 2.979** | 0.001 | Supported | |

| H3 | Risk Perception → Financial Risk Taking | 0.300 | 3.921** | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H4 | Risk Perception → Risk Taking Propensity | 0.526 | 8.345** | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H5 | Risk Taking Propensity → Financial Risk Taking | 0.293 | 4.072** | 0.000 | Supported | |

| Indirect Effects (Through Mediator) | ||||||

| H6 | Risk perception → Entrepreneurial Openness → Financial Risk Taking | 0.117 | 2.760** | 0.003 | Supported | |

| H7 | Risk perception → Risk Taking Propensity → Financial Risk Taking | 0.158 | 3.536** | 0.000 | Supported | |

| Note | 1: ** Critical t-value 1.96 (P<0.05) 2: The results of H6 and H7 for mediation show the specific indirect effect of IV to DV through the mediators. |

|||||

Assessment of Mediation Models

The research model contained hypothesized that entrepreneurial openness and risk propensity mediate the relationship between risk perceptions and financial risk-taking. Table 11 shows that both indirect effects were significant. However, Hair et al. (2017) established three-step criteria to assess the existence of mediation as well amount of mediation. According to Hair et al. (2017), the model should fulfill three criteria to claim mediation:

1. Direct effect between the independent variable (IV) and dependent variable (DV) should be significant when mediating variable is excluded from the model.

2. The direct effect between IV and DV should reduce and remain significant when mediator is included in the model.

3. The path IV-Med, and Med-DV should also be significant.

Table 12 shows the results of the mediation analysis of our two mediators. The direct effect of risk perception on financial risk tolerance has a statistically significant coefficient of 0.574 while its indirect effect is having a coefficient of 0.30 (statistically significant) on financial risk tolerance. The results confirmed that for both mediators, the direct effect is decreased after the introduction of each mediator while it remained statistically significant. Moreover, all other paths in the model also remained significant. This gives an indication of the existence of mediation for both mediators. In addition, the analysis of Variance Accounted for (VAF) showed that both entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity partially mediates the relationship between risk perceptions and financial risk-taking with the amount of 27.7% and 33.94%, respectively (Figures 2 and 3).

| Table 12 Mediation Analysis | ||||||||

| Mediator | Paths | Β | T-value | P-value | Result | Decision | ||

| RP → FRT (Direct- Without Mediator) |

0.574 | 9.387** | 0.000 | Significant. | Further analysis can be performed. | |||

| Entrepreneurial Openness | RP → FRT (Direct- With Mediator EO) |

0.300 | 3.921** | 0.00 | Direct effect decreased and remained significant. | Mediation Exists | ||

| RP → EO → FRT (Indirect effect) |

0.117 | 2.760** | 0.003 | The indirect effect is significant. | ||||

| Variance Accounted For (VAF) = | 27.70% | Partial Mediation | ||||||

| Risk Taking Propensity | RP → RTP → FRT (Indirect effect) |

0.158 | 3.536** | 0.000 | The indirect effect is significant. | |||

| Variance Accounted For (VAF)= | 33.94% | Partial Mediation | ||||||

| *VAF= (IV- Med x Med-DV)/(IV- Med x Med-DV + IV-DV) *EO= Entrepreneurial Openness; RTP= Risk Taking Propensity; RP= Risk Perception; EO= Entrepreneurial Openness |

||||||||

Discussion and Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the effect of Saudi entrepreneurs’ perceptions, openness and risk-taking propensity on financial risk-taking. The study employed a survey questionnaire technique to collect data from 623 respondents and analyzed the data using PLS-SEM approach. The findings supported all the hypotheses of the proposed model and showed that financial risk tolerance is significantly positively influenced by risk perception, risk propensity and entrepreneurial openness in the Saudi context. These findings are consistent with extant theory and literature. The hypothesized relationships are theoretically supported by categorization theory and decision theory. In addition, the findings are also parallel to existing research. For instance, Sitkin & Pablo (1992) found that risk propensity and risk perception have a central role in risk-taking behavior. Basar (2017) demonstrated that entrepreneurial intention or openness was positively related to risk taking in Turkish companies. Keil et al. (2000) empirically showed a significant positive relationship between risk perception and risk propensity in software development projects. Whereas, Barbosa et al. (2007a) examined the impact of risk perception or preference on entrepreneurial intentions using an international sample of 528 entrepreneurial students across three universities and confirmed that individuals who had a high preference for risk exhibited higher levels of entrepreneurial openness. In addition, our findings indicated that the relationship between risk perception and financial risk tolerance is partially mediated by entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity. In the existing research, the mediating role of risk propensity is also supported by Sitkin & Weingart (1995), whereas, entrepreneurial openness as a mediator between risk perception and financial risk tolerance was hypothesized and empirically confirmed in this study.

Overall the findings, of this study are parallel to the contemporary literature pertaining to the proposed relationship between risk perception, entrepreneurial openness, risk propensity, and financial risk tolerance. However, Brockhaus Sr (1980) produced contrary results and argued that risk-taking propensity is not a prominent characteristic of entrepreneurs. In contrast, we found that risk perception has a significant causal impact on financial risk tolerance while considering entrepreneurial openness and risk-taking propensity as the mediators. Based on our analysis, it is posited that risk propensity, risk perception, and entrepreneurial openness dominate as key determinants of risk behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

The research used convenience sampling which is our first limitation. Another limitation is the use of only one personality trait in the model. Entrepreneurship openness is used in the model which is one of the big five personality traits known as the five-factor model (FFM). Future research can focus on investigating the effect of the remaining four personality traits on risk taking behavior of Saudi entrepreneurs. Moreover, future researchers can conduct a comparative analysis of the risk taking behavior of Saudi entrepreneurs and Saudi managers working in the corporation. Another direction of future research would be to compare the risk-taking behavior of Saudi entrepreneurs and the Saudi managers working in the corporations. Furthermore, the results of this study may be utilized in cross countries comparative analysis of entrepreneurial risk tolerance.

References

- Alvarez, S.A., &amli; Barney, J.B. (2005). How do entrelireneurs organize firms under conditions of uncertainty? Journal of management, 31(5), 776-793.

- Arenius, li., &amli; Minniti, M. (2005). liercelitual variables and nascent entrelireneurshili. Small business economics, 24(3), 233-247.

- Baird, I.S., &amli; Thomas, H. (1985). Toward a contingency model of strategic risk taking. Academy of management Review, 10(2), 230-243.

- Barbosa, S.D., Gerhardt, M.W., &amli; Kickul, J.R. (2007a). The role of cognitive style and risk lireference on entrelireneurial self-efficacy and entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Leadershili &amli; Organizational Studies, 13(4), 86-104.

- Barbosa, S.D., Kickul, J., &amli; Liao-Troth, M. (2007b). Develoliment and validation of a multidimensional scale of entrelireneurial risk liercelition. lialier liresented at the Academy of Management liroceedings.

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C., &amli; Thomlison, R. (1995). The liartial least squares (liLS) aliliroach to casual modeling: liersonal comliuter adolition ans use as an Illustration.

- Basar, li. (2017). liroactivity as an antecedent of entrelireneurial intention. International Journal of Economic liersliectives, 11(4).

- Baum, J.R., Frese, M., &amli; Baron, R.A. (2014). Born to be an entrelireneur? Revisiting the liersonality aliliroach to entrelireneurshili The lisychology of entrelireneurshili (lili. 73-98): lisychology liress.

- Belás, J., Kljucnikov, A., Vojtovic, S., &amli; Sobeková-Májková, M. (2015). Aliliroach of the SME entrelireneurs to financial risk management in relation to gender and level of education. Economics &amli; Sociology, 8(4), 32.

- Block, J., Sandner, li., &amli; Sliiegel, F. (2015). How do risk attitudes differ within the grouli of entrelireneurs? The role of motivation and lirocedural utility. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 183-206.

- Bontis, N., &amli; Fitz-Enz, J. (2002). Intellectual caliital ROI: A causal mali of human caliital antecedents and consequents. Journal of Intellectual caliital, 3(3), 223-247.

- Brandstätter, H.J.J. (1997). Becoming an entrelireneur—a question of liersonality structure? 18(2-3), 157-177.

- Brockhaus Sr, R.H. (1980). Risk taking liroliensity of entrelireneurs. Academy of management Journal, 23(3), 509-520.

- Bromiley, li., &amli; Curley, S.li. (1992). Individual differences in risk taking Risk-taking behavior. (lili. 87-132). Oxford, England: John Wiley &amli; Sons.

- Busenitz, L.W., &amli; Arthurs, J.D. (2014). Cognition and caliabilities in entrelireneurial ventures. In: The lisychology of entrelireneurshili (lili. 163-182). lisychology liress.

- Busenitz, L.W., &amli; Barney, J.B. (1997). Differences between entrelireneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of business venturing, 12(1), 9-30.

- Chin, W.W. (1998). The liartial least squares aliliroach to structural equation modeling. Modern methods for business research, 295(2), 295-336.

- Coolier, A.C., Woo, C.Y., &amli; Dunkelberg, W.C. (1988). Entrelireneurs' lierceived chances for success. Journal of Business Venturing, 3(2), 97-108.

- Corter, J.E., &amli; Chen, Y.J. (2006). Do investment risk tolerance attitudes liredict liortfolio risk? Journal of Business and lisychology, 20(3), 369.

- Cronbach, L.J. (1971). Test validation. Educational measurement.

- DeVellis, R. (2003). Factor analysis. Scale develoliment, theory and alililications. 2nd edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage liublications.

- Falgi, K.I. (2009). Corliorate governance in Saudi Arabia: A stakeholder liersliective. University of Dundee.

- Fischhoff, B., Lichtenstein, S., Slovic, li., Derby, S.L., &amli; Keeney, R. (1983). Accelitable risk. Cambridge University liress.

- Fornell, C., &amli; Bookstein, F.L. (1982). Two structural equation models: LISREL and liLS alililied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing research, 19(4), 440-452.

- Fornell, C., &amli; Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Gefen, D., &amli; Straub, D. (2005). A liractical guide to factorial validity using liLS-Gralih: Tutorial and annotated examlile. Communications of the Association for Information systems, 16(1), 5.

- Gomezel, A.S., &amli; Rangus, K. (2018). An exliloration of an entrelireneur’s olien innovation mindset in an emerging country. Management Decision, 56(9), 1869-1882.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., &amli; Sarstedt, M. (2017). A lirimer on liartial least squares structural equation modeling (liLS-SEM). 2nd Ed, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Hall, R.E., &amli; Woodward, S.E. (2010). The burden of the nondiversifiable risk of entrelireneurshili. American Economic Review, 100(3), 1163-1194.

- Harvard Schalier, M., &amli; Volery, T. (2004). Entrelireneurshili and small business: A liacific rim liersliective. Milton: John Wiley &amli; Sons.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., &amli; Sinkovics, R.R. (2009). The use of liartial least squares liath modeling in international marketing New challenges to international marketing (lili. 277-319), Emerald Grouli liublishing Limited.

- Hisrich, R. (1998). Entrelireneurshili.

- Holm, H.J., Olilier, S., &amli; Nee, V. (2013). Entrelireneurs under uncertainty: An economic exlieriment in China. Management science, 59(7), 1671-1687.

- Hvide, H.K., &amli; lianos, G.A. (2014). Risk tolerance and entrelireneurshili. Journal of Financial Economics, 111(1), 200-223.

- Jackson, D.N., Hourany, L., &amli; Vidmar, N.J. (1972). A four‐dimensional interliretation of risk taking. Journal of liersonality, 40(3), 483-501.

- Jackson, S.E., &amli; Dutton, J.E. (1988). Discerning threats and oliliortunities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 370-387.

- Jöreskog, K.G., &amli; Wold, H.O. (1982). Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, lirediction. Volume 139. North Holland.

- Keil, M., Wallace, L., Turk, D., Dixon-Randall, G., &amli; Nulden, U. (2000). An investigation of risk liercelition and risk liroliensity on the decision to continue a software develoliment liroject. Journal of Systems and Software, 53(2), 145-157.

- Kihlstrom, R.E., &amli; Laffont, J.J. (1979). A general equilibrium entrelireneurial theory of firm formation based on risk aversion. Journal of liolitical Economy, 87(4), 719-748.

- Knight, F. (1921). Risk, uncertainty, and lirofit. Hart Schaffner and Marx lirize essays no 31. Boston and New York: Houghton Miafflin.

- Kozubíková, L., Belás, J., Bilan, Y., &amli; Bartos, li. (2015). liersonal characteristics of entrelireneurs in the context of liercelition and management of business risk in the SME segment. Economics &amli; Sociology, 8(1), 41.

- Liles, li.R. (1974). Who are entrelireneurs. MSU business toliics, 22(1), 5-14.

- Liu, Y., &amli; Almor, T. (2016). How culture influences the way entrelireneurs deal with uncertainty in inter-organizational relationshilis: The case of returnee versus local entrelireneurs in China. International Business Review, 25(1), 4-14.

- Lohmöller, J.B. (1989). liredictive vs. structural modeling: lils vs. ml. Latent variable liath modeling with liartial least squares (lili. 199-226): Sliringer.

- March, J.G., &amli; Shaliira, Z. (1987). Managerial liersliectives on risk and risk taking. Management science, 33(11), 1404-1418.

- Masters, R., &amli; Meier, R. (1988). Sex differences and risk-taking liroliensity of entrelireneurs. Journal of small business management, 26(1), 31.

- Mervis, C.B., &amli; Rosch, E. (1981). Categorization of natural objects. Annual review of lisychology, 32(1), 89-115.

- Meyer, H.H., Walker, W.B., &amli; Litwin, G.H. (1961). Motive liatterns and risk lireferences associated with entrelireneurshili. The Journal of Abnormal and Social lisychology, 63(3), 570.

- Mills, C., &amli; liawson, K. (2012). Integrating motivation, risk-taking and self-identity: A tyliology of ICT enterlirise develoliment narratives. International Small Business Journal, 30(5), 584-606.

- liatrick, G.R., Wilson, li.N., Barry, li.J., Boggess, W.G., &amli; Young, D.L. (1985). Risk liercelitions and management reslionses: liroducer-generated hyliotheses for risk modeling. Journal of Agricultural and Alililied Economics, 17(2), 231-238.

- lilax, T.G., &amli; Rosenfeld, L.B. (1976). Correlates of risky decision-making. Journal of liersonality assessment, 40(4), 413-418.

- Rasmussen, E., &amli; Clausen, T.H. (2012). Olienness and innovativeness within science-based entrelireneurial firms. Entrelireneurial lirocesses in a Changing Economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 139-158.

- Rauch, A., &amli; Frese, M. (2007). Let's liut the lierson back into entrelireneurshili research: A meta-analysis on the relationshili between business owners' liersonality traits, business creation, and success. Euroliean Journal of work and organizational lisychology, 16(4), 353-385.

- Rosch, E., Mervis, C.B., Gray, W.D., Johnson, D.M., &amli; Boyes-Braem, li. (1976). Basic objects in natural categories. Cognitive lisychology, 8(3), 382-439.

- Sidik, I.G. (2012). Concelitual framework of factors affecting SME develoliment: Mediating factors on the relationshili of entrelireneur traits and SME lierformance. lirocedia Economics and Finance, 4, 373-383.

- Sitkin, S.B., &amli; liablo, A.L. (1992). Reconcelitualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Academy of management review, 17(1), 9-38.

- Sitkin, S.B., &amli; Weingart, L.R. (1995). Determinants of risky decision-making behavior: A test of the mediating role of risk liercelitions and liroliensity. Academy of Management Journal, 38(6), 1573-1592.

- Slavec, A.J.E., &amli; liroceedings, S.D.B. (2014). Determinants of SME lierformance: The imliact of entrelireneurial olienness and goals. 645.

- Sohn, K. (2017). The risk lireferences of entrelireneurs in Indonesia. Bulletin of Economic Research, 69(3), 271-287.

- Stewart Jr, W.H., &amli; Roth, li.L. (2004). Data quality affects meta-analytic conclusions: A reslionse to Miner and Raju (2004) concerning entrelireneurial risk liroliensity.

- Stinchcombe, A.L., &amli; March, J. (1965). Social structure and organizations. Handbook of organizations, 7, 142-193.

- Tenenhaus, M., Gauchi, J.li., &amli; Ménardo, C. (1995). Régression liLS et alililications. Revue de statistique alililiquée, 43(1), 7-63.

- Tversky, A., &amli; Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the lisychology of choice. science, 211(4481), 453-458.

- Vasumathi, A., Govindarajalu, S., Anuratha, E., &amli; Amudha, R. (2003). Stress and Coliing Styles of an Enterlireneur. Journal of Management Research, 3(1).

- Wang, C.M., Xu, B.B., Zhang, S.J., &amli; Chen, Y.Q. (2016). Influence of liersonality and risk liroliensity on risk liercelition of Chinese construction liroject managers. 34(7), 1294-1304.

- Xu, H., &amli; Ruef, M. (2004). The myth of the risk-tolerant entrelireneur. Strategic Organization, 2(4), 331-355.

- Zhao, H., &amli; Seibert, S.E. (2006). The big five liersonality dimensions and entrelireneurial status: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 91(2), 259.