Research Article: 2022 Vol: 28 Issue: 2S

Entrepreneurial Success and Sustainability: Towards A Conceptual Framework

Joseph Chikwendu Ezennia, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Emmanuel Mutambara, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Citation Information: Ezennia, J.C., & Mutambara, E. (2022). Entrepreneurial success and sustainability: Towards a conceptual framework. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 28(S2), 1-16.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Success, Sustainability, Conceptual framework, Factors

Abstract

Entrepreneurs have been challenged ever since, with several factors which impede their entrepreneurial activities towards successful entrepreneurship and sustainability. An entrepreneur cannot progress without overcoming the challenge that poses as a threat towards harnessing the imminent business opportunity identified. These challenges (factors) are experienced in different forms depending on the location, circumstances and the individual. However, variables from various theoretical factors were surveyed; sociological, psychological, innovative and the need for high achievement factors, and the results revealed led to the development of the conceptual framework of entrepreneurial success and sustainability.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a welfare enhancing business activity that takes place under good institutions that play important roles in channelling entrepreneurial imagination and initiatives into productive activities that enable consumers to maximise their utility at lower costs (Ezennia & Mutambara, 2019). These activities, accordingly benefits both the entrepreneur and society at large as well as generate economic wealth that is informed by innovativeness and the ability to adapt in order to fill the gaps in the market (Ezennia & Mutambara, 2019).

Jackson (2016) acknowledged that entrepreneurship was noted to be the best activity for stimulating economic growth in developing countries, hence, the interest of universities encouraging students to start-up their own businesses to enhance employment for themselves and others (Jackson, 2016). Despite the immense contributions of the entrepreneurs towards economic growth and development of a country’s economies, they face several challenges which hinder their entrepreneurial activities towards successful entrepreneurship and sustainability. Hence, the need for a conceptual framework that will guide entrepreneurs to improve on their performances, gain competition prowess and improve on business sustainability towards attaining successful entrepreneurship.

This article presents various economic theories which influence the entrepreneur towards entrepreneurship. However, in the literature review, various theoretical frameworks were reviewed and discussed, followed by the presentation of the study’s conceptual framework.

Literature Review

Theoretical Frameworks

Theories, according to Labaree (2013), are formulated in order to explain, predict, and understand a social phenomenon, particularly to question and add to existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounding assumptions. The scholar (Labaree, 2013) adds that a theoretical framework is the structure which supports a theory of a research study. The author further concurs that the theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge.

According to Simpeh (2011), several theories have been developed by scholars to explain the field of entrepreneurship. The author suggests that these theories have their origins in economics, psychology, sociology, anthropology and management. Literature reveals that the most common theories which support entrepreneurship are economic entrepreneurship theories, psychological entrepreneurship theories, sociological entrepreneurship theory, anthropological entrepreneurship theory, opportunity–based entrepreneurship theory and resource-based entrepreneurship theories (Bayrón, 2016; Frese, 2009; Heinrichs & Walter, 2013; Linden, 2015). These theories are discussed below.

Economic Entrepreneurship Theories

Economic entrepreneurship theories focus on the Knightian ideas of risk-bearing, which assumes that entrepreneurs are modelled as being heterogeneous with respect to risk aversion (Kanbur, 1979). Proponents of this theory (Meza & Southey, 1996) believe that some individuals possess identical abilities but they differ in their perceptions of the risks involved in owning a business venture. The scholars argue that overly optimistic individuals are successful entrepreneurs, as opposed to those who are not overly optimistic. Economic entrepreneurship theories have become the dominant theories in recent times because of the global financial crisis. This theory has its origin in the classical and neoclassical theories of economics as well as the Austrian Market Process (AMP) (Simpeh, 2011). These theories, which fall under the ambit of economic entrepreneurship theories, are discussed as follow.

Classical Theory

Scholars, such as Ricardo (1817); Smith (1776), assume that the classical theory has its roots in free trade, specialisation, and competition. The proponents believe that the theory emerged as a result of Britain’s industrial revolution which occurred in the mid-1700 and lasted until the 1830s. A study reveals that those who ascribe to the theory argue that it directs the role of the entrepreneur in terms of the production and distribution of goods and services into the competitive market (Say, 1803). Other scholars (Murphy, Liao & Welsch, 2006) share their views by asserting that the classical theorists suggest that there are three main factors of production, namely; land, capital, and labour. However, it has been found that several objections were raised against the theory in that it failed to describe the dynamic upheaval generated by entrepreneurs of the industrial revolution (Murphy et al., 2006).

Subsequently, Nadrifar, Bandani & Shahryar (2015) also believe that the classical theory is very prominent among management theories. The scholars’ postulate that the classical theory was developed to predict and control the behaviours in an organisation. The theory has unique features, such as chain of command, the division of labour, one-sided top-down influence, and authoritarian leadership styles (Nadrifar et al., 2015). The classical theory consists of other theories such as the scientific management theory, administrative management theory and the management bureaucratic theory (Ferdous, 2016).

Neo-classical Theory

The neo-classical theory was introduced due to the several criticisms that were levelled against the classical theory. Royer (2014) points out that the neo-classical theory is mostly used by economists. Those who ascribe to the neo-classical theory believe that the value of products and the allocation of resources are determined by the costs which are associated with production as well as the tastes and preferences of the consumers (Royer, 2014). This theory lies on marginal analysis, which assumes that the additional quantity of a commodity that is purchased or sold is based on additional utility, revenue, or the cost associated with the last unit.

Murphy, et al., (2006) assume that the economic system is made up of exchange participants, exchange occurrences, and the effect of exchange on other market actors. Although the neo-classical theory has been instrumental in the field of management, some criticisms were levelled against it. The strongest criticism is that the aggregate demand overlooks the uniqueness of individual-level entrepreneurial activity (Murphy et al., 2006). According to Bula (2012), critiques argue that an economy cannot be static. Therefore, a state of static equilibrium is unrealistic. The critics further argue that abnormal profits in the entrepreneurial world cannot always be achieved. Another criticism is that rational resource allocation does not cover the complexity of market-based systems.

Austrian Market Process (AMP)

The AMP is the third theory which emerged under the economic entrepreneurship theories. According to Simpeh (2011), the criticism against the neo-classic theory has led to the development of AMP. Murphy, et al., (2006) posit that the neo-classical movement has acknowledged the impracticality of identifying all important information in an economic system so as to gain an understanding of the phenomena within it. Those who ascribe to the AMP believe that the specific knowledge acquired by the entrepreneur has much to do with their activity. The AMP movement focuses more attention on phenomena logically observed rather than empirically.

Moreover, AMP is credited to Joseph Schumpeter (1934), who focuses on human action in the context of an economy of knowledge. According to Schumpeter (1934), the entrepreneur is considered the driver of a market-based system. Thus, entrepreneurs are noted for their innovativeness which can serve as impulses for the motion of market economy. The scholar argues that the AMP addresses a central question of how to harness knowledge required when discovering business opportunities and making good decisions when it is dispersed idiosyncratically throughout the system. The AMP rejects the assumptions that circumstances are repeatable, which always lead to the same outcomes in an economic system. Rather, it believes that entrepreneurs are incentivised to use episodic knowledge.

Kirzner (1973) suggests that AMP is based on three main conceptualisations. The first conceptualisation is the arbitraging market where business opportunities emerge for given market actors, as others ignore some opportunities or undertake suboptimal activities. The second conceptualisation is the alertness to profit-making opportunities, where the entrepreneurs discover an entrepreneurial advantage. The last conceptualisation is that ownership is distinct from entrepreneurship. Knight (1921) points out that the entrepreneurship business does not require the ownership of resources, an idea that adds context to uncertainty and risk. The above three conceptualisations indicate that every opportunity is unique in its own way and therefore previous activity cannot be used to determine outcomes reliably.

Although the AMP model has contributed to the field of entrepreneurship, it is not without criticisms. An important criticism is that the market systems are not purely competitive, they are characterised by antagonist co-operation. Another criticism against the AMP model is that resource monopolies can serve as a major constraint to competition and entrepreneurship. The model has further been criticised on the basis that fraud /deception and taxes/controls also have significant impact on the market system activities. The last criticism is that private and state firms have some differences but both can be entrepreneurial (Knight, 1921). The criticisms against the AMP model have resulted in the emergence of the psychological entrepreneurship theories.

Psychological Entrepreneurship Theories

Dedekuma & Akpor-Robaro (2015) believe that psychological entrepreneurship theories are based on the individual personal characteristics. The authors (Dedekuma & Akpor-Robaro, 2015) concur on the premise that psychological entrepreneurship theories assert that the successful entrepreneurs possess certain personality characteristics which distinguish them from ordinary people. The view expressed by the above scholars reaffirms the position of Landstrom (1998), who explains that the level of analysis in psychological theories is based on the individual.

Further, Landstrom (1998) argues that the psychological entrepreneurship theories focus on personality characteristics which define entrepreneurship. Similarly, Linden (2015) suggests that those who ascribe to this theory assume that there is a psychological profile common to entrepreneurs. The scholars suggest that the psychological entrepreneurship theories are made of theories such as personality traits, a need for achievement and locus of control. The theories are discussed below.

Personality Trait Theory

Personality trait theory is one of the dominant theories which distinguishes successful entrepreneurs from ordinary entrepreneurs. Antoncic (2009) postulates that entrepreneurship is based on the personality of the entrepreneur. Personality traits has been described as the stable qualities that a person displays in given situations (Coon, 2004). In other words, personality traits are the enduring inborn characteristics or potentials of an individual that naturally make people successful entrepreneurs. Similarly, Llewellyn & Wilson (2003) explain that personality traits are more specific constructs that explain consistencies in the way people behave, which help to explain why different people react differently to the same situation.

Further, the trait theorists (Carland, Hoy & Carland, 1988; McCrae, 1994; Mueller & Thomas, 2001; Pervin, 1994) assume people are partly shaped through social learning processes in early childhood and partly determined by heritage or environmental influences. The proponents of the trait perspective believe that some individuals possess specific dispositions (qualities) which lead them to self-select entrepreneurial careers. Entrepreneurship literature identifies several attributes, traits, or skills that are associated with entrepreneurial behaviour and successes (Deakins & Freel, 2009; Ramana, Aryasri & Nagayya, 2008). The most common characteristics or qualities associated with successful entrepreneurs include the need for high achievement, risks taking or tolerance for risks, tolerance for ambiguity, good locus of control, creativity, high level of management skills and business know-how, and innovation (Chen & Lai, 2010; Hornaday, 1982).

Similarly, Singh & Rahman (2013) argue that the qualities most frequently associated with the success of the entrepreneurs are innovation, persistence, self-confident, positive attitude, problem solving, need for dependence, and risk taking. However, on the contrary, Desai (2001) discovers that the most crucial personality traits which lead to entrepreneurship success are emotional stability, personal relations, consideration, and tactfulness. Ehigie & Umoren (2003) also identify that common personality traits leading to success are self-concept, perceived managerial competence, work stress, and business commitments. Again, Chell (2008) argues that besides the predominantly researched traits and other approaches to personality, the big five factors (extraversion, emotional stability, openness to experience, agreeableness, conscientiousness) of personality trait approach are also relevant in determining entrepreneurial success.

Furthermore, a study by Zhao & Seibert (2006) reveals that with the exception of extraversion, the five factors discriminated well between entrepreneurs and managers. The meta-analysis carried out by Barrick & Mount (1991) suggests that conscientiousness produced the highest effect sizes in entrepreneurship as well. Also, it has been found that those who possess these attributes are emotionally resilient and have high mental energy, they are hard workers, show intense commitment and perseverance, thrive on a competitive desire to excel and win, and tend to be dissatisfied with the status quo and thus desire improvement. Equally, they believe that they can make much difference, and are individual with moral integrity and vision (Simpeh, 2011).

Notwithstanding the contributions of the personality trait theory, it has not been without criticisms. Therefore, the personality trait theory has been criticised because of the inconsistencies in findings, small sample sizes, and the heterogeneity of concepts used to describe entrepreneurs. Gartner (1989) criticised the traits like innovativeness on the ground that it amounts to little more than a simple re-labelling of the term entrepreneur without adding any useful insight to the phenomenon of entrepreneurship. Other critics also argue that, although the personality approach to entrepreneurship is useful in explaining entrepreneurial behaviour, it should be supplemented by sound and theoretically justified developments of modern personality psychology.

Locus of Control

Locus of control has been considered one of the aspects of the personality traits. The term “locus of control” was first used by Rotter in the 1950s who refers to it as a person’s perception about the underlying main causes of events which happen to them. Inegbenebor (2007) refers to locus of control as the extent to which individuals believe that they can control events that affect them. Similarly, according to Bulmash (2016), locus of control involves the perception of having personal control of situations and not being at the mercy of external circumstances. Further, LefCourt (1976) postulate that locus of control is a term which explains the degree to which a person assumes or feels responsibility for the success or failure in their life as opposed to feeling that external agents, like luck, are in control.

Consequently, there are two types of locus of control, namely; internal and external locus of control. Researchers such as Rao & Moulik, (1978); Rao & Pareek (1978); Sarupriya (1982), in their studies, found that an internal locus of control is the most important characteristic of entrepreneurs. Rotter (1966) assumes that individuals with an internal locus of control believe that they are able to control life events. Lefcourt (1976); Phares (1976) believe that an internal locus of control differs from the external locus of control. A significant difference is that persons with an internal locus of control appear to take more initiative and are more responsible in performance situations when compared to those with an external locus of control. Also, the scholars argue that those with an internal locus of control seek and utilise information more efficiently and seem to be more in touch with external realities. These characteristics possessed by the internal persons are essential factors in enhancing achievement motivation. Empirical research demonstrates that the internal locus of control is an entrepreneurial characteristic that has been well documented in entrepreneurship literature (Cromie, 2000; Ho & Koh, 1992; Koh, 1996). Bonnett & Furnham (1991) point out that the internal locus of control was found to be positively associated with individuals who aspire to become entrepreneurs.

Nonetheless, those with an external locus of control, on the other hand, believe that life’s events are the result of external factors, such as chance, luck, or fate. Thus, they assume that there are certain events which are beyond their control (Rotter, 1966). Similarly, Lefcourt (1976) posits that those with an external locus of control have the belief that certain environmental factors such as fate, luck, and powerful others are at work in any given situation which required the need for the attainment of goals.

Need for Achievement Theory

Need for achievement theory is another aspect of the psychological entrepreneurship theories. Pervin (1980) concurs that while the personality trait theory pays critical attention to enduring inborn qualities and locus of control theory focuses on the individuals’ perceptions regarding the rewards and punishments in their lives, the need for achievement, propounded by McClelland (1961), points out how human beings have a strong desire to succeed, accomplish, or excel in various fields or endeavours. David McClelland (1961), a psychologist in this theory, attempts to provide explanations to entrepreneurial emergence and behaviour by individuals as well as to provide understanding of the factors which influence the development of an entrepreneurial society. One of the rationales behind the introduction of the need for achievement theory is to identify the role of psychological factors in stimulating the mindset of individuals to becoming entrepreneurs.

Further, according to McClelland (1961), individuals who pursue entrepreneurial like careers are more motivated by the psychological need to achieve and are high in “need achievement”. The scholar states that some individuals are spurred into entrepreneurship most importantly by the intrinsic motive to achieve for the sake of achievement. The theorist suggests that human behaviour is affected by three needs, namely; a need for power (n-Pow), a need for achievement (n-Ach), and a need for affiliation (n-Aff). However, he cautions that an individual’s nurture and culture can influence any of these personalities (Dedekuma & Akpor-Robaro, 2015). Furthermore, Holland (1985), in his study, also made a similar call that the interaction of work environment and personality are likely to affect performance in a career. The three various types of ‘Need’ are discussed below.

Need for Power (n-Pow)

This is an individual’s desire to influence other peoples’ behaviours as a per personal wish. In other words, it is the desire for a person to have control over others and to be influential (Rishipal, 2012). Invariably, according to McClelland (1965), people who are motivated by power have a strong urge to be influential and controlling. They desire for their views, opinions, and ideas to be dominating and thus want to lead others. Nonetheless, such people are motivated by the need for reputation and self-esteem. The proponents argue that people with greater power and authority will perform better than those possessing less power.

Need for Achievement (n-Ach)

Accordingly, McClelland (1961), the n-Ach motive is the most important among the various needs which contributes to entrepreneurial development. The scholar explains that this need makes the entrepreneur behave with great aspirations and expectations as well as optimism and enthusiasm in their pursuits. McClelland (1965) believes that individuals with a high need for achievement motivation are more likely to engage in the instrumental activities that are necessary for success in an entrepreneurial situation as opposed to individuals with low in achievement motivation. Rishipal (2012), in his study, also confirms that those who are high in need for achievement excel, accomplish a set of goals, and struggle for success.

Need for Affiliation (n-Aff)

The need for affiliation is a need for open and sociable interpersonal relationships. The need for affiliation is the desire for relationships based on co-operation and mutual understanding (McClelland, 1965). The individuals who are motivated by affiliation have the urge for a friendly and supportive environment. Such individuals are effective performers in a team. These people want to be liked by others. One of the studies conducted by Rishipal (2012) suggests that individuals who desire to establish good relationships with others are more successful than those with a poor relationship with friends.

However, the need for achievement theory is one such theory of entrepreneurship which receives much attention from practitioners and scholars in the field of business and entrepreneurship. Several psychologists, such as Thomas Begley and David Boyd, have given support to the McClelland school of thought because it provides explanations to entrepreneurial emergence and behaviour which distinguishes successful entrepreneurs from ordinary business-persons. Hence, Kuratko & Hodgetts (1998) claim that McClelland’s theory is useful in explaining the unique characteristics possessed by successful entrepreneurs, such as tolerance for ambiguity and a pattern of behaviour characterised by a chronic, incessant struggle to achieve more and more in as short time as one possibly can.

Nevertheless, McClelland’s need for achievement theory is not without any criticism. As a result, Burns (2016) critiques the theory on the basis that it concentrates much effort on entrepreneurial motivation and holds constant the issues of entrepreneurial flair, the ability to take business risks, and the concern regarding a desire to start a new business. Again, Burns (2016), argues that the theory focuses on such traits that are inherent in the need for achievement and hence, in the entrepreneurial person.

Sociological Entrepreneurship Theory

The sociological entrepreneurship theory focuses mainly on the analysis of the social context, processes, and the effects of entrepreneurial activity within society (Ruef & Lounsbury, 2007). It was argued that entrepreneurship can be construed either narrowly as purposive action leading to the creation of new formal organisations, or more broadly as any to introduce durable innovations in routines, technologies, organisational forms, or social institutions (Ruef & Lounsbury, 2007).

Further, Reynolds (1991), in his study, argues that there are four social contexts that relate to entrepreneurial opportunity. The first social context, according to the scholar, is social networks. The scholar believes that social networks build social relationships and bonds that promote trust and not opportunism. The second social context is called, “the life course stage context”. He explains that the life course stage has to do with the analysis of life situations and characteristics of persons who desire to become entrepreneurs. The scholar opines that people’s experiences have the potential or tendency to influence their thoughts and actions in order to do something meaningful with their lives. The third social context is ethnic identification. The author argues that the social background of individuals determines their entrepreneurial success. For instance, the scholar believes that disadvantaged groups are more likely to violate all obstacles and strive hard for success, spurred on by their disadvantaged background in order to make life better. The fourth social context, according to the scholar, is called “population ecology”. The scholar assumes that the social environment plays a crucial role in determining the survival of entrepreneurial businesses. He identifies the political system, government regulations, customers, competitors, and workers, as some of the environmental factors which influence entrepreneurial businesses.

Furthermore, according to Edewor, Abimbola & Ajayi (2014), the sociological perspective considers two major approaches, namely; the supply side approach and the demand side approach. The scholars argue that the supply side perspective has both psychological and sociological dimensions. The psychological dimension has to do with attributing entrepreneurship and its practices to the presence of certain traits in ‘special individuals’, which are missing in others. As discussed above, successful entrepreneurs are identified with some unique personality traits, which include achievement, internal locus of control, and a risk-taking propensity, amongst other things. The sociological supply side, on the other hand, has to do with attributing entrepreneurship to ‘special individuals’, which focuses on the compelling influence of society on engendering entrepreneurial practices. According to Edewor, et al., (2014), the sociological supply side perspective includes presence of congenial cultural attributes that are facilitating of entrepreneurial practices, social class or ethnic group that extols the credibility of entrepreneurial activities or that are compatible with entrepreneurship.

Moreover, Max Weber in Ruef & Lounsbury (2007) argues that the sociological supply-side of the sociological entrepreneurship theory pays much attention to economic development. The author (Max Weber) postulates that the high rate of economic development recorded in Western societies relative to other cultures was a corollary of the presence of values, such as individualism, an ascetic self-denial which discourages extravagant lifestyles, positive attitudes towards work, savings, and investment. The scholar in his comparative study, pointed out that the great accumulation of wealth, which has resulted in the emergence of capitalism in Europe and North America, was due to protestant ethic. The theorist believes that the ethic culture in Europe and North America encouraged abstinence from life’s pleasures, an austere lifestyle and rigorous self-discipline (Ruef & Lounsbury, 2007).

Anthropological Entrepreneurship Theory

The anthropological entrepreneurship theory was the fourth entrepreneurship school of thought after the sociological school of thought was critiqued. Anthropology is concerned with the study of origins, developments, customs, and beliefs of a particular community. It studies, mostly, the culture of people in a community (Simpeh, 2011). The proponents of this theory suggest that for an entrepreneur to succeed, they need to consider social and cultural contexts. The scholar postulates that the culture in a particular community largely influences the kind of business venture a person should create. The cultural entrepreneurship model states that one’s culture influences how the new venture is created.

Similarly, other scholars (Mitchell, Smith, Morse, Seawright, Peredo & McKenzie, 2002) found that anthropology studies the origins, artefacts, culture, norms, beliefs, and customs of people. The scholars in their study argue that ethnicity has a significant impact on the attitudes and behaviours of people. They postulate that the socio-economic, ethnic, and political affiliations among people are often reflected in culture. According to North (1990) & Shane (1994), the culture environment has the potential of producing different attitudes and entrepreneurial behaviour differences.

Opportunity–Based Entrepreneurship Theory

Accordingly, studies (Fiet, 1996; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000) identify the importance of the concept of “opportunity” as the most crucial factor, which provides understanding of entrepreneurship and economic change. The term “opportunity discovery” has been applied in entrepreneurship literature to mean that information sufficient to define an “opportunity” exists at a certain point in the process of discovery (Shane and Eckhardt, 2003). Scholars such as Alvarez & Barney (2005); Stevenson & Jarillo (1990) argue that entrepreneurs need to have a detailed or comprehensive perception of “opportunity” so as to serve as a cognitive objective for those who perceive the opportunity.

However, it has been argued that if the initial perception of opportunity is rudimentary, and thus insufficient to serve as a definite cognitive objective to guide an entrepreneur, the concept of “opportunity discovery” might be inappropriate. Shane (2000), in his study, argues that entrepreneurs recognise opportunities rather than search for information that stimulates opportunity discovery. According to Stevenson & Jarillo (1990), entrepreneurs search for opportunities irrespective of the resources they currently control. Alvarez & Busenitz (2001) also concur that opportunities surface when entrepreneurs have distinctive insights into the value of certain resources or a combination of resources that might be bundled in new ways.

Resource-Based Entrepreneurship Theories

The resource-based entrepreneurship theory was propounded by Barney (1991), it explains the competitive advantage and organisational performance of firms. The RBV is based on the premise that organisations’ competitive advantages and subsequent performance originate in the resources and capabilities controlled by the organisations (Barney, 1991). Newbert (2007) suggests that in a number of studies, the domains of entrepreneurship have addressed the significance of resources in entrepreneurial firms. However, most of such studies conceptualised resources as direct predictors of firm performance. According to Aldrich (1999), the RBV stresses the importance of resources such as social, financial, and human resources. Davidson & Honing (2003) also point out that the financial, social and human capital represents three classes of theories, which fall under the ambit of the RBV. These theories are discussed below.

Financial/Liquidity Theory

Research suggests that access to finance is one of the key resources which determines the success of new entrepreneurial ventures (Blanchflower, Oswald & Stutzer, 2001; Evans & Jovanovic, 1989). However, it has been argued that financial distress is recognised as a driving force behind many corporate decisions (Gryglewicz, 2011). The author suggests that corporate finance literature has long been interested in how firms generate uncertain cash flows and how they disburse them. The liquidity theory assumes that people with strong financial capital are more able to acquire resources to effectively exploit entrepreneurial opportunities and set-up new ventures as opposed to those with weak financial capital (Clausen, 2006).

Further, Alvarez & Busenitz (2001), in their study, suggest that some entrepreneurs have some unique resources that facilitate the recognition of new opportunities and the gathering of new resources for their emerging firm. Other scholars, such as Aldrich (1999); Anderson & Miller (2003); Shane & Venkataraman (2000), in their studies, argue that some entrepreneurs are more able to recognise and exploit opportunities as opposed to others due to the fact that they have better access to information and knowledge. Furthermore, the scholars state that asymmetric information could underlie the entrepreneurial venture that gives rise to funding constraints.

Social Capital or Social Network Theory

The social network theory received much interest form entrepreneurship researchers in the mid-1980s and extended into SMME, organisational, and market research fields (Johannisson & Nilsson, 1989). Clausen (2006) argues that entrepreneurs are embedded in a larger social network structure which forms a significant proportion of their opportunity structure. Shane & Eckhardt (2003) assert that people may have the ability and knowledge to recognise that a given entrepreneurial opportunity exists yet may still lack the social connections necessary to convert such opportunities into a new venture.

Further, Johannisson (1986) suggests that entrepreneurs who invest their time and energies into building social networks stand the chance to achieve better results compared to those who failed to invest in social networks. Johannisson (1986) also points out that personal social networks are major assets to the potential entrepreneur to develop the individual character that the entrepreneur is trying to impose on his business. Filion (1990), in his study, also postulates that networking should be considered part of a wider process which includes the “technical know-how” of entrepreneurs and their vision. The scholar suggests that entrepreneurs differ according to the size of their business and the types of social networks that they can call on to supplement their expertise and knowledge and the way in which they use and develop these networks. He claims that social networks have the tendency to improve the success of the entrepreneur in a number of ways at different stages of the development of the business.

Furthermore, other scholars, such as Dubini & Aldrich (1991); Birley (1985); Hutt & Van Hook (1988), discover that social networks provide entrepreneurs with opportunities to gather useful information from a wide variety of sources to test out their existing ideas, to get referred to appropriate specialists by their contacts, to obtain moral support, and to gain the use of others who have an interest in the entrepreneur's welfare. Again, a recent study by Nowi?ski & Rialp (2016) also confirms that social networks are dynamic and evolving from the moment entrepreneurs conceive a business idea and then form a new venture, to when they develop it from the moment of establishment.

Human Capital Entrepreneurship Theory

The human capital theory focuses on two main factors, namely, education and experience (Becker, 1975). Human capital is regarded as the most valuable asset among all other resources such as finance, equipment, and materials. The scholar defines human capital as the knowledge and skills possessed by an individual, this can be general or specific in nature. Mincer (1974) explains that, originally, the human capital theory has related investments in the development of knowledge and skills to the income distributions of employees. In recent time, the human capital theory has gained popularity in the field of entrepreneurship and attracted a substantial empirical effort from many entrepreneurship researchers (Unger, Rauch, Frese & Rosenbusch, 2011).

The resource-based entrepreneurship theory seems the most appropriate theory to measure the entrepreneurial success. The theory is based on the premise that access to resources by founders is an important predictor of opportunity-based entrepreneurship and new venture growth (Alvarez & Busenitz, 2001). The premise or assumption of this theory is evident in the current situation in the global market. The theory further emphasises the importance of financial, social and human resources in new entrepreneurship ventures.

It is emphasised that the success of any entrepreneurship in the 21st century depends on the above three resources. These factors, when effectively combined, will enable entrepreneurs to achieve, to identify business opportunities, create new ventures, increase their performance, as well as achieve sustainable competitive advantages. Unger, et al., (2017) state that the human capital theory contributes to improvement in the performance and the sustainable competitive advantage of firms.

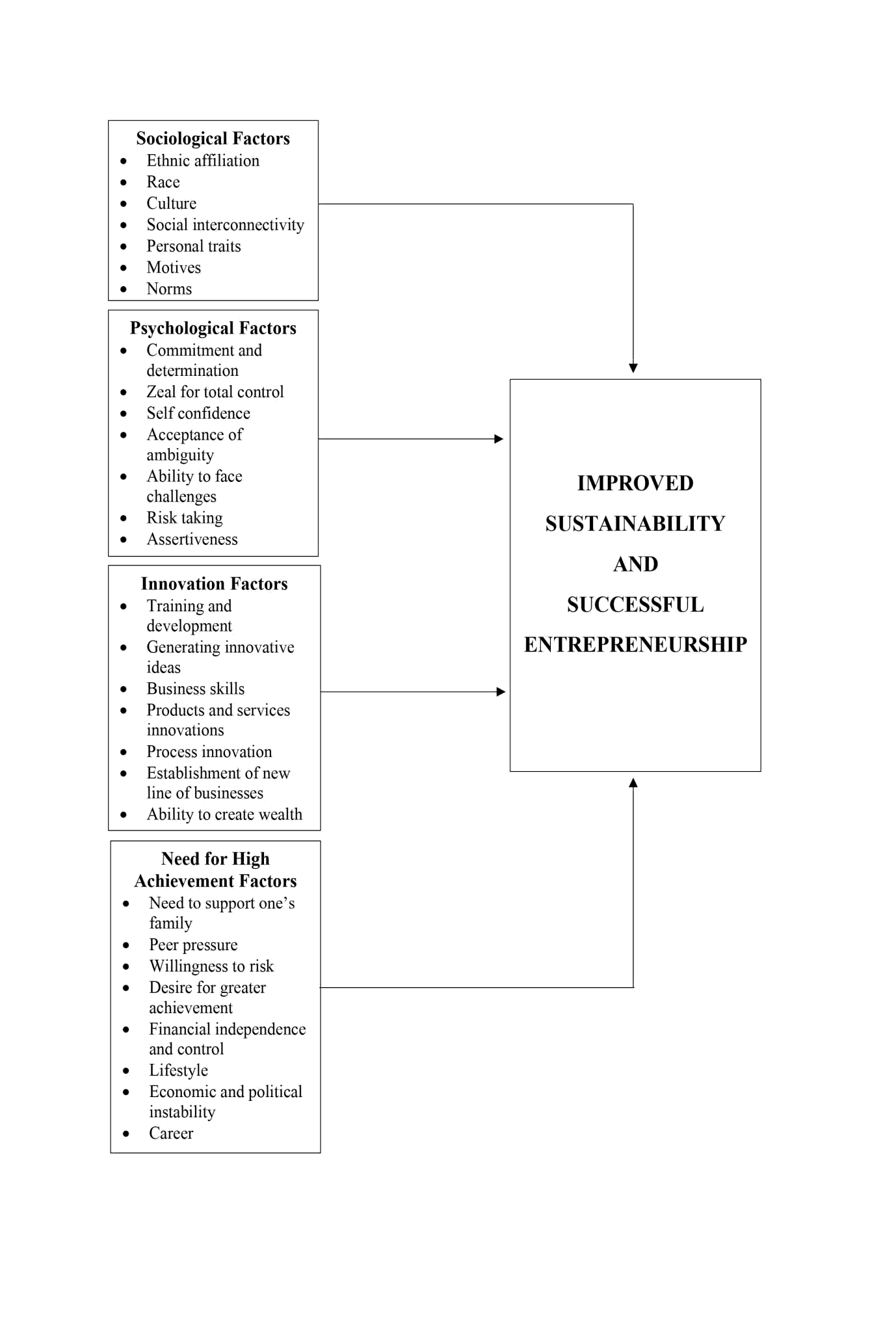

Conceptual Framework

The identified framework for the study is the ‘multi-dimensional factors of entrepreneurial emergence’. The framework was adopted from Dedekuma & Akpor-Robaro (2015); Simpeh (2011) and improved by the study. The framework has some limitations which were identified by the researcher. The scholars Dedekuma & Akpor-Robaro (2015); Simpeh (2011) in their studies acknowledge that certain factors influence the start-up of entrepreneurship ventures worldwide and that economic, social and psychological factors affect the set-up and survival of entrepreneurship ventures. However, they fall short of identifying those social, psychological and economic factors that do affect entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Multi-Dimensional Factors of Entrepreneurial Emergence

Accordingly, this study took major steps further towards identifying the specific factors which fall under the ambit of the social-culture, psychological, innovation and the need for high achievement factors affecting entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship ventures. In achieving this feat, a conceptual framework was developed to indicate the various factors that influence entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship, especially the African immigrant-owned micro businesses. The figure below presents the full-designed conceptual framework of the study.

Furthermore, another important observation made by the researcher is that the multi-dimensional factors of entrepreneurial emergence and other frameworks fail to acknowledge political factors which affect entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial ventures. Consequently, most of these factors are incorporated into the study’s developed framework, the study found the aforementioned factors to have severe implications on the entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial ventures. Then again, as reflected in the framework above, the researcher believes that these factors, when properly handled and managed, will allow entrepreneurs to improve on their performances, gain competition prowess and improve on business sustainability towards attaining successful entrepreneurship.

Conclusion

The research reviewed the related theories on entrepreneurship, namely, psychological entrepreneurship, sociological entrepreneurship, anthropological entrepreneurship, opportunity–based entrepreneurship and resource-based entrepreneurship theories. The study emphasised more on resource-based entrepreneurship theory and place emphatically on the importance of financial, social and human resources in new entrepreneurial ventures. In this competitive era the success of any business venture depends on financial, social and human resources in new entrepreneurial ventures. The study further presented the conceptual framework which guides the investigation and finally provided more solutions to measuring entrepreneurial emergence, success and sustainability in a new designed and developed conceptual framework presented.

References

Aldrich, H. (1999). Organisations evolving. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Alvarez, S., & Barney, J. (2005). Discovery and creation: alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=900200

Alvarez, S., & Busenitz, L., (2001). The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory.Journal of Management, 27(6), 755-775.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Anderson, A., & Miller, C. (2003). Class matters: Human and social capital in the entrepreneurial process.The Journal of Socio-Economics, 32(1), 17-36.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Antoncic, B., (2009). The entrepreneur’s general personality traits and technological developments.World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 53(3), 236-241.

Barney, J., (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage.Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

Barrick, M.R., & Mount, M.K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis.Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1-26.

Bayrón, C.E. (2016). Social cognitive theory, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions: Tools to maximise the effectiveness of formal entrepreneurship education and address the decline in entrepreneurial activity. Revista Griot (Etapa IV-Coleccióncompleta),6(1), 66-77.

Becker, G.S. (1975). Investment in human capital: Effects on earnings. In Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, Second Edition.NBER, 13-44.

Birley, S. (1985). The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process.Journal of Business Venture, 1(1), 107-117.

Blanchflower, D., Oswald, A., & Stutzer, A. (2001). Latent entrepreneurship across nations?European Economic Review, 45, 680-691.

Bonnett, C., & Furnham, A. (1991). Who wants to be an entrepreneur? A study of adolescents interested in a young enterprise scheme.Journal of economic psychology, 12(3), 465-478.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Bula, H. O. (2012). Evolution and theories of entrepreneurship: A critical review on the Kenyan perspective.International Journal of Business and Commerce, 1(11), 81-96.

Bulmash, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial resilience: Locus of control and well-being of entrepreneurs.Journal of Entrepreneurship Organisation and Management, 5, 171-179.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Burns, P. (2016). Entrepreneurship and small business.

Carland, J.W., Hoy, F., & Carland, J.A.C. (1988). Who is an entrepreneur? Is a question worth asking?American Journal of Small Business, 12(4), 33-39.

Chell, E. (2008). The entrepreneurial personality: A social construction. New York, NY: Routledge, 2008.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Chen, Y., & Lai, M. (2010). Factors influencing the entrepreneurial attitude of Taiwanese tertiary-level business students.Social Behaviour and Personality, 38(1), 1-12.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Clausen, T.H. (2006). Who identifies and exploits entrepreneurial opportunities? Centre for Technology. Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo.

Coon, D. (2004). Introduction to psychology (9th Edition). Minneapolis: West Publishing Company.

Cromie, S. (2000). Assessing entrepreneurial inclinations: Some approaches and empirical evidence.European journal of work and organisational psychology, 9(1), 7-30.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Davidson, P., & Honing, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs.Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301-331.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Deakins, D., & Freel, M. (2009). Entrepreneurship and small firms (5th edition) London: McGraw-Hill.

Dedekuma, S.E., & Akpor-Robaro, M.O.M (2015). Thoughts and theories of entrepreneurial emergence: A critical review of the pioneer perspectives and their relevance in Nigerian society of today.IIARD International Journal of Economics and Business Management, 1(8), 104-119.

Desai, V. (2001). Dynamics of entrepreneurial development and management. New Delhi: Himalaya Publishing House.

Dubini, P., & Aldrich, H. (1991). Personal and extended networks are central to the entrepreneurial process.Journal of Business Venturing, 6(5), 305-313.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Edewor, P.A., Abimbola, O.H., & Ajayi, M.P. (2014). An exploration of some sociological approaches to entrepreneurship.European Journal of Business and Management, 6(5), 18-24.

Ehigie, B.O., & Umoren, U.E. (2003). Psychological factors influencing perceived entrepreneurial success among Nigerian women in small-scale businesses.Journal of International Women’s Studies, 5(1), 78-95.

Evans, D.S., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints.Journal of political economy, 97(4), 808-827.

Ezennia, J.C., & Mutambara, E. (2019). Entrepreneurial psychological characteristics that influence African immigrant-owned micro businesses in Durban, South Africa.Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 25(4), 1-15.

Ferdous, J. (2016). Organisation theories: From classical perspective.International Journal of Business, Economics and Law,9(2), 1-6.

Fiet, J. (1996). The informational basis of entrepreneurial discovery.Small Business Economics, 8(6), 419-430.

Filion, L. J. (1990). Entrepreneurial Performance, Networking, Vision and Relations.Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 7(3), 3-13.

Frese, M. (2009). Towards a psychology of entrepreneurship - An action theory perspective.Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 5(6), 437-496.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Gartner, W.B. (1989). Who is an entrepreneur? Is the wrong question.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 12(2), 47-68.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Gryglewicz, S. (2011). A theory of corporate financial decisions with liquidity and solvency concerns.Journal of Financial Economics, 99(2), 365-384.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Heinrichs, S., & Walter, S. (2013). Who becomes an entrepreneur? A 30-years-review of individual-level research and an agenda for future research. Arbeitspapiere des Instituts für Betriebswirtschaftslehre, Universität Kiel.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Ho, T.S., & Koh, H.C. (1992). Differences in psychological characteristics between entrepreneurially inclined and non-entrepreneurially inclined accounting graduates in Singapore. Entrepreneurship, innovation and change: an International Journal, 1(2), 43-54.

Holland, J.L. (1985). Making vocational choices. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hornaday, J.A. (1982). Research about living entrepreneurs. In Kent, C.A, Sexton, D.A. and Vesper, K.H. 1982. Encyclopaedia of entrepreneurship. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Hutt, R.W., & Van Hook, B.L. (1988). The Use of outside advisers in venture start-ups. In Kirchoff, B.A., Long, W.A., McMullan, W.E., Vesper, K.H. and W.R. Wetzel (Editions), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 1988. Wellesley MA: Babson College, 216--218.

Inegbenebor, A.U. (2007). Pharmacists as entrepreneurs or employees: The role of locus of control.Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 6(3), 747-754.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Jackson, T. (2016) South African universities turn to entrepreneurship to solve employment issues: The next degree of entrepreneurship? African Business, 84-85.

Johannisson, B. (1986). Network strategies: Management technologies for entrepreneurship and change.International Small Business Journal, 5(1), 19-30.

Johannisson, B., & Nilsson, A. (1989). Community entrepreneurs: Networking for local development.Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 1, 3-19.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Kanbur, S.M. (1979). Of risk taking and the personal distribution of income.Journal of Political Economy, 87(4), 769-797.

Kirzner, I.M. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press.

Knight, F.H. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. New York: Houghton-Mifflin.

Koh, C.H. (1996). Testing hypotheses of entrepreneurial characteristics: A study of Hong Kong MBA students.Journal of Managerial Psychology, 11(3), 12-25.

Kuratko, D.F., & Hodgetts, R.N. (1998). Entrepreneurship: A contemporary approach. The Dryden Press. Harcourt Brace College Publishers Orlando, U.S.A.

Labaree, R. (2013). Organising your social sciences research paper: Theoretical framework. USC Libraries, University of Southern California.

Landström, H. (1998). Informal investors as entrepreneurs: Decision-making criteria used by informal investors in their assessment of new investment proposals.Technovation,18(5), 321-333.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Lefcourt, H.M. (1976). Locus of control: Current trends in theory and research. New Jersey, Erthaum: Hilldale.

Linden, P. (2015). Entrepreneurship: Theory and application in a university arts management setting.Journal of the Music and Entertainment Industry Educators Association, 15(1), 138-145.

Llewellyn, D.J., & Wilson, K.M. (2003). The controversial role of personality traits in entrepreneurial psychology. Education and Training, 45(6), 341-345.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Co.

McClelland, D.C. (1965). Toward a theory of motive acquisition.American Psychologist, 20, 321–333.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

McCrae, R.R. (1994). New goals for trait psychology.Psychological Inquiry, 5(2), 148-153.

Meza, D.D. & Southey, C. (1996). The borrower's curse: Optimism, finance and entrepreneurship.The Economic Journal, 106(435), 375-386.

Mincer, J. (1974). Schooling, experience and earnings. New York: Columbia University Press.

Mitchell, R.K., Smith, J.B., Morse, E.A., Seawright, K.W., Peredo, A., & McKenzie, B. (2002). Are entrepreneurial cognitions universal? Assessing entrepreneurial cognitions across cultures.Entrepreneurship,Theory and Practice, 26(4), 9-32.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Mueller, S.L., & Thomas, A.S. (2001). Culture and entrepreneurial potential: A nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness.Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 51-63.

Murphy, P.J., Liao, J., & Welsch, H.P. (2006). A conceptual history of entrepreneurial thought.Journal of Management History, 12(1), 12-35.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Nadrifar, A., Bandani, E., & Shahryari, H. (2015). An overview of classical management theories: A review article.International Journal of Science and Research, 5(9), 83-86.

Newbert, S.L. (2007). Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research.Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 121–146.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

North, D.C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. New York: Norton.

Nowinski, W. & Rialp, A. (2016). The impact of social networks on perceptions of international opportunities.Journal of Small Business Management, 54(2), 445-461.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Pervin, L.A. (1980). Personality: Theory, assessment and research. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Pervin, L. A. (1994). A critical analysis of current trait theory.Psychological Inquiry, 5(2), 103-113.

Phares, E.J. (1976). Locus of control and personality. Morristown, New Jersey: Gilver Burdett.

Ramana, C.V., Aryasri, A.R., & Nagayya, D. (2008). Entrepreneurial success in SMEs based on financial and non-financial parameters. The Icfai University Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 5(2), 32-48.

Rao, T.V., & Pareek, U. (1978). Developing entrepreneurship: A handbook. New Delhi, India: Learning Systems.

Reynolds, P.D. (1991) Sociology and Entrepreneurship: Concepts and Contributions.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2), 47-70.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Ricardo, D. (1817). On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. London.

Rishipal, N.J. (2012). Need for Achievement an Antecedent for Risk Adaptiveness among Entrepreneurs.Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 12(22), 1-10.

Rotter, J.B. (1966). Generalised expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement.Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 609.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Royer, J.S. (2014). The neoclassical theory of co-operatives: Part I.Journal of Co-operatives, 28(1), 1-19.

Ruef, M., & Lounsbury, M. (2007). Introduction: The sociology of entrepreneurship. In The sociology of entrepreneurship. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 1-29.

Sarupriya, D.S. (1982). A study of psychological factors in managerial and entrepreneurial effectiveness. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Gujarat University.

Say, J.B. (1803). Of the demand or market for products.Critics of Keynesian Economics. New Rochelle (NY): Arlington House. 12-22.

Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credits, interest and the business cycle. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Shane, S.A. (1994). The effect of national culture on the choice between licensing and direct foreign investment.Strategic Management Journal, 15(8), 627-642.

Shane, S. & Eckhardt, J. (2003). The individual-opportunity nexus. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research (161-191). Springer, Boston, MA.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Shane, S. & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research.Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217-226.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Simpeh, K.N. (2011). Entrepreneurship theories and empirical research: A summary review of the literature.European Journal of Business and Management, 3(6), 1-8.

Singh, H.R., & Rahman, H. (2013). Entrepreneurs’ Personality Traits and their Success: An Empirical Analysis.The International Journal of Social Science and Management, 3(7), 90-104.

Smith, A. (1776). The wealth of nations. New York: The Modern Library.

Stevenson, H., & Jarillo, C. (1990). A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management.Strategic Management Journal, 11, 17-27.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Unger, J.M., Rauch, A., Frese, M., & Rosenbusch, N. (2011). Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review.Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 341–358.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Zhao, H., & Seibert, S.E. (2006). The big five personality dimensions and entrepreneurial status: A meta-analytical review.Journal of applied psychology, 91(2), 259-271.

Crossref , GoogleScholar , Indexed

Received: 06-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. AEJ-21-7898; Editor assigned: 08-Dec-2021, PreQC No. AEJ-21-7898(PQ); Reviewed: 17-Dec-2021, QC No. AEJ-21-7898; Revised: 29-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. AEJ-21-7898 R); Published: 06-Jan-2022