Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 6

Entrepreneurial Motivation in the Global South: Addressing Gender Marginalization

Chioma Onoshakpor, Robert Gordon University

Imaobong James, Robert Gordon University

Tolulope Ibukun, Robert Gordon University

Bridget Irene, Coventry University

Citation Information: Onoshakpor, C ., James, Imaobong., Ibukun, T., Irene, B., (2023). Entrepreneurial Motivation In The Global South: Addressing Gender Marginalization. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 27(6),1-15

Abstract

This article sets out to the issues of gender marginalisation and entrepreneurial motivation is increasingly gaining interest in management, mainly to address social and gender exclusion. This paper explores the perceived differences in the motivating factors for women and men in choosing entrepreneurship as a career in a global south economy (Nigeria). This paper explores the perceived differences in the motivating factors for women and men in choosing entrepreneurship as a career in a global south economy (Nigeria). The study examines the role of patriarchy as it is perceived in Nigerian society, and how this might impact on the role of choosing entrepreneurship. These driving forces for entrepreneurship are typically divided into push and pull aspects. The push/pull theory is used to explore gender marginalisation, experienced by women in Nigeria.

Keywords

Female Entrepreneurship, Gender, Entrepreneurship in Nigeria, Women in Business, Patriarchy, Entrepreneurial Motivation.

Introduction

Most research on gender marginalisation tends to focus on the global north, which may not apply to the global south. Furthermore, it is yet unknown whether the push and pull factors that motivate entrepreneurship in developing countries differ based on gender. It is essential to draw attention to these gender inequalities, mainly because of factors that motivate women and how they operate their enterprises. This paper explores the perceived differences in motivating factors for women and men in choosing entrepreneurship as a career in Nigeria's global south economy. According to research, people are inspired to become entrepreneurs for various reasons, such as financial success, status, self-realization, It will be interesting to analyse these reasons in the context of a country that still experiences some level of gender marginalization, as is the case of Nigeria. These driving forces for entrepreneurship are typically divided into push and pull aspects (McClelland et al., 2005; Schjoedt and Shaver, 2007; Segal et al., 2005). Push factors are frequently used to group elements with a bad connotation, such as unemployment, financial hardship, and poverty (Amit and Muller, 1995; Carsrud and Brannback, 2011; Kirkwood, 2009). While pull factors are the favourable elements that entice people to become entrepreneurs, such as recognising an opportunity (Dawson and Henley, 2012; Kirkwood, 2009; Manolova et al., 2008). According to several studies, pull factors predominate over push factors (see, for instance, Segal et al., 2005; Shinnar and Young, 2008). However, since most of this research is from the global north, it may not apply to the global south, where push factors (such as economic difficulties and a lack of jobs) are more likely to predominate than pull forces (i.e., opportunities). In addition, it is yet unknown whether push and pull factors that affect both men and women to start their own business in a developing country differ based on gender. It is essential to draw attention to these gender inequalities and uncover if this influences their reasoning for choosing entrepreneurship. Thus, the following two research questions highlight this study:

1. What motivates women to start a business in the global south?

2. How do the motivating factors for women differ from their male counterparts in the global south?

Literature Review

Gender Marginalization in Nigeria

Since Nigeria's founding in 1914, when it may be traced back to that country's inception, gender disparity has been a problem for the country's progress. Despite decades of attempts, women still suffer in most measures of socioeconomic development and political involvement, as they make up most of the poor, unemployed, and socially disadvantaged (Mukoro, 2014). Despite existing constitutional legislation and the adherence of both the current and previous governments to regional and international human rights treaties and conventions, Kura and Yero (2013) contend that the rights of women and girls in Nigeria are gravely abused and devalued. Women have not been viewed favourably as business owners for the past three decades (ref). This is because many women in Sub-Saharan African nations continue to face discrimination due to their gender (Kuada, 2009). Researchers (Makama, 2013; Garba, 2011) blame the patriarchal system for gender inequality, unequal households, and unequal market access in emerging nations, particularly Nigeria. The gender-differentiated phrases in inheritance rights are accepted and even encouraged by society. Additionally, society tolerates domestic and sexual abuse of women and pays variable remuneration for similar or equal work. According to (Salaam, 2003), Nigeria's culture and religion contribute to society's indoctrination into thinking that men are the superior gender.

For example, not being married becomes a stigma that most women are eager to shed as they age. Indeed, society's emphasis on marriage for women is so constricting that being single, divorced, or a spinster is a horror (Ojiakor, 1997). According to (Mukoro, 2014), women in Nigerian society are mostly impacted by gender inequality. Women frequently do not have the right to own money and property; instead, they are treated as an item to be inherited along with the property, violating their human rights (Okafor, 2015). According to (Dorojaye & Dorojaye, 2014), this is confirmed by the fact that, in Igbo customary law, a male child has the right to inherit, but a female child does not. Male sexuality is accepted in Nigerian society, whereas female sexuality is frowned upon. Boys are, therefore, free to express their sexual impulses, while girls are expected to be sexually passive. While boys attend schools, women and girls in rural communities must walk long distances to get wood and water for cooking, do the dishes, and provide care for the aged, ill, and disabled (Dormekpor, 2015). Odozi (2012) claims that women have less access to economic, political, and social resources than men do, which causes them to be relatively underprivileged.

Eshiet (2019) attribute these occurrences to globalisation since women are obliged to bear the brunt of structural adjustment programmes, prioritising the technological revolution, which impacts their overall success due to their low educational levels. Nigeria is currently ranked 128th globally, with a gender difference that has narrowed by 63.5%, according to the 2020 Global Inequality Index (WEF, 2020). Nigeria has never had a female head of state, which is important to remember. However, the desire of women to be economically independent, as well as their role and contribution as female entrepreneurs in changing the labour market, have been increasingly recognised in the literature on entrepreneurship (Goffee & Scase, 1985).

The Context of Entrepreneurship in Nigeria

Existing studies have shown that entrepreneurial activities drive economic growth, creates employment opportunities, and wealth (Brush & Cooper, 2012; Huggins et al., 2018). Studies show that in a developing economy like Nigeria, entrepreneurial activities play an important role, not only in economic development but in steering the socio-economic landscape of the country. In a report by the National Bureau of Statistics (2014), SMEs in Nigeria are seen to account for 97% of the total businesses in the country, contributing 87.9% of the net jobs and 48% of the industrial output in terms of value-addition (Olukayode & Somoye, 2013). Besides, SMEs also contribute 48% of the country's GDP (UNDESA, 2019). According to GEM (2012), Nigeria is considered one of the world’s most entrepreneurial countries as 35 out of 100 Nigerians are engaged in some kind of entrepreneurial activity or the other. As such, the Nigerian government, have introduced numerous programmes and national agencies to support the development and growth of enterprises in the developing countries (Ajayi, 2016; Ogundana et al., 2021). Notable among them are the National Directorate of Employment (NDE), Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN), Peoples Bank of Nigeria (PBN), National Bank of Commerce and Industry, Microfinance Banks, National Economic Reconstruction Fund (NERFUND) and the National Economic Empowerment and Development Scheme (NEEDS). However, studies have observed that many of these policy interventions aimed at motivating individuals into entrepreneurship have recorded failures due to poor implementation, corruption, excessive red tapes, and bureaucracy (Igwe et al., 2018; Ihugba et. al., 2013; Thaddeus, 2012). Yet, individuals continue to stream towards entrepreneurship despite the failed attempts of these programmes to motivate potential entrepreneurs to start and run successful businesses (UNDESA, 2019). Moreover, it is still unclear what factors motivate individuals to venture into entrepreneurship and how these motivating factors differ by gender.

Theoretical Underpinning

With entrepreneurship being associated with innovation and economic growth, there has been vast array of studies investigating the factors that influence entrepreneurship (Patrick et al, 2016; Choi and Kim, 2021; Hughes 2003; Amit and Muller, 1995; Parveen et al, 2020; Harms et al 2004). The Push and Pull Theory has been used to explore the differences in the underlying factors that make men and women choose entrepreneurship. This theory suggests that individuals are ‘pulled’ or incentivised into entrepreneurship as they seek out greater job control, independence, expected earnings, and social development (Choi and Kim, 2021; Hughes 2003; van der Zwan et al, 2016). Patrick et al (2016) also suggested high levels of education and experience as pull factors because individuals with such have the skills to access resources that are beneficial to entrepreneurship. The other spectrum of this theory states that individuals are ‘pushed’ or motivated to become entrepreneurs due to dissatisfaction with their positions and seek to make a change away from undesired or unwanted situations (Amit and Muller, 1995; Parveen et al, 2020; Harms et al 2004; van der Zwan et al, 2016). Uhlaner and Thurik (2007) suggests that individuals are ‘pushed’ into entrepreneurship because of the imbalance between their current and desired state. (Patrick et al., 2016) further stated that some individuals are pushed into entrepreneurship when they are unable to find salaried employment due to low levels of education and experience.

This means push factors, which can be personal (divorce) or external factors (discrimination at workplace, lack of flexibility, restructuring/downsizing) have negative undertone, while pull factors are incentives towards entrepreneurship (Uhlaner and Thurik, 2007; Hughes, 2003; Parveen et al, 2020; Tlaiss, 2015). Amit and Muller (1995) suggested that individuals who become entrepreneurs through pull factors tend to be financially successful compared to those who are entrepreneurs due to push factors.

Carr (1996) found that ‘advanced age and education’ influence both men and women towards entrepreneurship in comparison to salaried employment. With regards to gender differences, women are suggested to less likely be pulled into entrepreneurship due to variableness and uncertainty associated with the rewards of entrepreneurship as they are more risk averse than men (Choi and Kim, 2021; Patrick et al, 2016). In an earlier study, (Carr, 1996) stated that education, previous work experience and age, which are human capital factors, are the strongest factors that influence men towards venture creation while marital status and family responsibilities (having young children) motivate women. The latter finding is supported by (Jennings & Mcdougald, 2007) and (Loscocco & Bird, 2012) who emphasised that women tend to bear more family responsibilities than men and this was highlighted as one of the pull factors into entrepreneurship (Itani et al, 2011). This is in contrast to (Patrick et al, 2016)’s finding that family responsibility associated with young children ‘pushes’ instead of ‘pulls’ married women into entrepreneurship. The authors found that married women are pulled into entrepreneurship in U.S. cities with excellent gender-role attitudes while unmarried women are pulled in cities with excellent entrepreneurial activities.

With regards to push factors, (Jamali, 2009) &(Itani et al., 2011) suggested women are motivated towards venture creation due to gender inequality, which include glass ceiling within professions, as well as workplace or labour market discrimination. (Itani et al., 2011) further suggested that other push factors for women could be inadequate income, redundancy and job dissatisfaction. Also, the authors suggested that women may be pushed towards entrepreneurship because of economic situations such as recessions and high unemployment rates. In the study by (van der Zwan et al., 2016), findings revealed that men have a higher probability of being pulled into entrepreneurship rather than women as the venture is created out of personal interest and desire to ‘take advantage of a business opportunity’. This study will build on the Push and Pull Theory and investigate the factors that incentivise and motivate entrepreneurship among men and women in a patriarchal society like Nigeria.

Methodology

To understand the impact of gender and entrepreneurial motivation, a comparative analysis of data from both male and female entrepreneurs is used. Furthermore, this study purposefully takes data from two different sectors, the real estate sector and the food/accommodation services sector, which are the two dominant sectors of male and female entrepreneurs respectively in Nigeria to identify if any sectoral differences are evident. This study hopes to provide useful opportunity to explore male motivation versus female motivation differed or are similar in the Nigerian context.

We utilised the purposive and snowballing sampling technique to recruit respondents for this study. These sampling techniques were useful for obtaining the information we required from those respondents that possessed such information (Holton, 2008). Due to limited theories on gender marginalisation and entrepreneurial motivation in the global south, an exploratory study is deemed suitable, as it allows the understanding of the experiences and perspectives of the research respondents. This study adopted a constructive grounded theory methodology (GTM) (Charmaz, 2014) to develop a theory grounded in systematically collected and analysed qualitative data through semi-structured interviews (Bryant & Charmaz, 2007; Birks and Mills, 2011). The preliminary literature review was conducted to engage analytically with the collected data by stimulating theoretical sensitivity (Kelle, 2007; Creswell, 2012; Corbin and Straus, 2015), however, this did not interfere with the theme's emergence and theory discovery (Charmaz, 2014). A robust understanding of what motivates men and women to choose entrepreneurship in the Global South (Nigeria) was developed and the impact on the type and motivation of female entrepreneurs in this region see Table 1.

| Table 1 Overview of Interview Participants | |||||

| Respondents ( R) | Gender | Marital Status | No. of employees | Sector of operation | No. of years of operation |

| Respondent 1 | Female | Married | 7 | Food/accommodation | 10 |

| Respondent 2 | Male | Married | 35 | Food/accommodation | 12 |

| Respondent 3 | Female | Single | 1 | Food/accommodation | 4 |

| Respondent 4 | female | Married | 20 | Food/accommodation | 7 |

| Respondent 5 | female | Married | 1 | Food/accommodation | 6 |

| Respondent 6 | female | Single | 3 | Food/accommodation | 3 |

| Respondent 7 | female | Married | 40 | Food/accommodation | 18 |

| Respondent 8 | female | Married | 50 | Food/accommodation | 11 |

| Respondent 9 | male | Married | 2 | Food/accommodation | 4 |

| Respondent 10 | male | Single | 5 | Food/accommodation | 3 |

| Respondent 11 | male | Married | 25 | Food/accommodation | 16 |

| Respondent 12 | female | Married | 12 | Food/accommodation | 15 |

| Respondent 13 | female | Married | 3 | Food/accommodation | 10 |

| Respondent 14 | female | Married | 50 | Food/accommodation | 12 |

| Respondent 15 | female | Single | 2 | Food/accommodation | 15 |

| Respondent 16 | Male | Married | 8 | Food/accommodation | 10 |

| Respondent 17 | Male | Married | 10 | Real Estate | 10 |

| Respondent 18 | Female | Single | 5 | Real Estate | 3 |

| Respondent 19 | Male | Married | 1 | Real Estate | 4 |

| Respondent 20 | female | Single | 1 | Real Estate | 3 |

| Respondent 21 | Male | Married | 5 | Real Estate | 3 |

| Respondent 22 | Male | Married | 50 | Real Estate | 7 |

| Respondent 23 | female | Single | 10 | Real Estate | 3 |

| Respondent 24 | Male | Married | 5 | Real Estate | 3 |

| Respondent 25 | Male | Married | 50 | Real Estate | 8 |

| Respondent 26 | Male | Married | 5 | Real Estate | 8 |

| Respondent 27 | Male | Married | 9 | Real Estate | 17 |

| Respondent 28 | Male | Single | 5 | Real Estate | 25 |

| Respondent 29 | female | Married | 3 | Real Estate | 12 |

| Respondent 30 | female | Married | 10 | Real Estate | 16 |

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews on Zoom online platform and lasted a minimum of 45 minutes. The data was collected through a purposive sampling of 30 owners/managers of hospitality (food and accommodation) and the real estate sector. The sampling conforms to the following criteria: men and women operating small or medium businesses in the hospitality and real estate sector in the global south and have been in operation for at least 3 years. The interviews were recorded with the consent of the participants and transcribed electronically with detailed proofreading (Cassia et al., 2012).

Analysis was done concurrently and iteratively with data collection and constant comparative analysis to allow a review of data collection and better theory discovery (Eisenhardt 1989). The matrices technique was adopted as an analytical tool for pattern matching and data categorisations (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The abductive approach of moving between a theoretical concept and new empirical data enables grounded theory development. This process was not a linear process but rather an iterative process of data collection, analysis and theorizing. The iterative process of considering and comparing previous literature, data and emerging theory allows for the validity and reliability of the findings (Yin, 1994). The following coding procedure was adopted for as a process of integrating and refining theory: open coding, axial, coding and selective coding. At open coding data were out into categories and subcategories, each research analysed the data individually and the subcategories were later explored using axial coding. Selective coding identified the interrelationships among main categories and further interprets core categories which create the basis for theory development (Kempster & Parry, 2011). These codes and interpreted constructs are presented in table 2 below.

| Table 2 Data Structure | ||

| First order codes | Second order codes | Interpreted constructs |

| Narratives around motivation to go into entrepreneurship to be for financial gains purely | Financial motivation | Factors that happens in a person’s live that pushes the person to exit the workplace and into entrepreneurship |

| Narratives around motivation to go into entrepreneurship to be born out of non-profit motivation, to benefit others | Internal motivations | |

| Narratives around motivation to go into entrepreneurship to achieve one’s life long goals | Self-actualization | |

| Narratives around motivation to go into entrepreneurship to be the boss of one’s self and be responsible for one’s decision making | Greater autonomy | Factors that happens in person’s live that pulls the person away from the workplace and into entrepreneurship |

| Narratives around motivation to go into entrepreneurship to gain work satisfaction as they will be involved with something they love doing | Work satisfaction | |

| Narratives around motivation to go into entrepreneurship due to a gap identified in the market | Gap identification | |

Result and Findings

The authors pose the research questions asked at the beginning of the research and use the data obtained to help answer these questions in relation with existing literature.

What motivates women to start a business in the global south?

The literature on women entrepreneurship and motivation suggests that females, are more focused on social contribution to society rather than economic contribution e.g more interested in creating a sense of value in the community. This has made some others propose that this has a direct link to the kinds of businesses they run and the size of those businesses. However, the findings of this study though align with this thinking, have also highlighted a parallel thinking. This study showed that women are both pushed and pulled into entrepreneurship (See Table 2). As a push factor, particularly, our findings show that female entrepreneurs in Nigeria are more likely motivated by external economic conditions such as job insecurity in the Nigerian labour market. See R17:

… you know the job insecurity uncertainties in the private sector is something else, so you always need a backup plan…

The issue of job insecurity is an issue that is prevalent in the Nigerian economy irrespective of gender. However, the findings from the interview results reveal that mostly women entrepreneurs were affected by the issue of insecurity in employment. This suggest that there are more reasons specific to the way the females are constructed which makes job insecurity specific to women. Considering that Nigeria is a Patriarchal society, and women must bear alone the brunt of childbearing and rearing, challenges around maternity leave and the willingness of companies to grant it, continues to impact the rise of women in the workforce which constantly deters women and pushes them into entrepreneurship (Irene, 2016). This is consistent with prior studies (Devine, 1994; Winn, 2004) that revealed that due to a continuing lack of progress within the workplace, women may be lured into entrepreneurship. Similarly, some of the women including respondent R18, R6, R8 identified that the presence of a ‘glass ceiling’ hindering their career development in an employee’s role was another factor that pushed them into entrepreneurship – mostly as a backup plan.

However, as a pull factor, our findings showed that female entrepreneurs are also motivated by the need to gain greater autonomy. See what R3 says:

….okay I have a lot of energy and when I started out with the nine to five I would sit at my desk literally do everything I’m asked to do and will try to generate more work to do and still get done with it and still have so much idle time, I’m someone who wants to give a hundred per cent of myself to anything I’m doing so while I was working for my bosses I didn’t feel right to also do things on the side…

This demonstrates a need to achieve by the female entrepreneur, a trait uncommon in the general academic literature. For example, according to (Kandel &Massey, 2002), women are generally reserved, unambitious and unentrepreneurial. The findings also reveal that women, including respondent R7, R14, R15, R16 were motivated into starting an enterprise because of the flexibility entrepreneurship offers. This is mainly because women are often more likely to be faced with the need to juggle together family and work responsibilities, thereby needing total autonomy to be able to manage both together (Fierrman, 1990; Irene, 2016). According to Respondent R7:

……and I like the fact that my time is mine I decide how I do it and I decide what I do when I do which is what only an enterprise can do…

The comment made by R7 aligns with the conclusions made by Konrad and Langton (1991) who posit that family issues and responsibility can influence the career choices of women because it is important to them. Family-related factors such as family policies and family obligations (DeMartino and Barbato, 2003; Onoshakpor, Cunningham and Gammie., 2022), domestic commitments (Marlow, 2002), and the need for work-family balance (Jennings and McDougald, 2007; Kirkwood and Tootell, 2008) have been found to be important for the female entrepreneur. These factors though labelled as push factors, according to Verheul et. al., (2006) are important entrepreneurship motivation factors irrespective of gender.

Another pull factor was identified when female respondents stated that they became entrepreneurs because of the identified gap in the market. For example, R3 and R7 commented respectively.

… okay I mean for me I see an opportunity and I'm thinking what I can do here right and how can I take advantage;

…. I found out I was basically cooking for almost all my friend's events so I could as well be paid while doing the job.

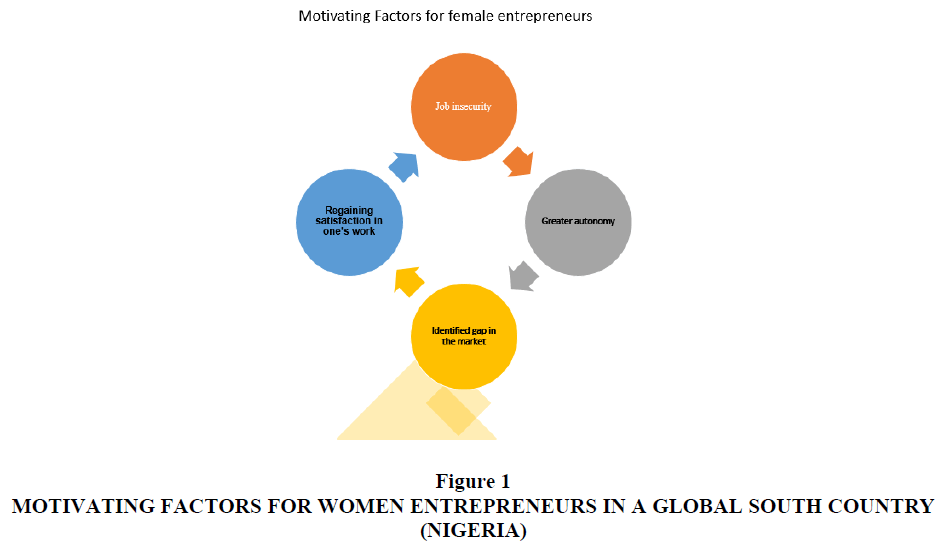

These commentaries by R3 and R7 can be categorised as ‘pull factors’. This is contrary to prior studies (Kandel & Massey, 2002) that indicate that only male entrepreneurs can identify business opportunities in the market, this therefore highlights the benefit of researching entrepreneurship in context- in this case the global south economy where arguably resources are scare. This research has demonstrated that female entrepreneurs possess the opportunistic tendency that a typical male entrepreneur possesses in a global north economy, see figure 1.

Figure 1 below shows a graphical representation of a combination of pull and push factors motivating female entrepreneurs in Nigeria to choose entrepreneurship as a career.

Additionally, our findings do not align with the extant literature about women mainly being pushed into entrepreneurship and making them set up businesses mostly in the service sector (Kuratko & Hodgetts, 1995) as this study has recorded female entrepreneurs operating in a male dominated real estate sector.

6.2. How do the motivating factors for women differ from their male counterparts in the global south?

To understand the lived experiences of female entrepreneurs in the global south and what motivates them to join entrepreneurship, it will be beneficial to compare the results against their female counterparts. The findings revealed that respondents in this study were motivated by a complex system of interacting factors that included both push and pull factors (See Table 2). Male respondents were majorly motivated by the idea of being self-employed. This is supported by prior literature where entrepreneurship is often described as a male domain (Ahl, 2006; Holmquist and Sundin, 1989; Ljunggren and Alsos, 2001; Verheul et al., 2012). In that regard, respondent R2 and R7 stated respectively that:

…a long-time dream from when I was 12 years old, my mother was a trader, seeing what she does and assisting her in what she does make me what to do this…. it birthed in me such passion to want to do this… R2;

…entrepreneurship is something that runs in my blood you know all my life that's what I've been wanting to be- to run my business because while I was growing up you know I was sewing, I was a tailor you know and I grew the business to a point where I was sewing clothes and taking them to the UK to sell….R7

This indicate that men might consider that entrepreneurship is a sector mainly for men. Besides, men are mostly introduced to the business world early in their lifetime. Parents in the developing economy region will normally introduce the family business to their male children because they believe the male child is more superior to the female child and he can handle the business better than the female child. On the contrary, a female child is expected to get married and will change her surname in the process. Women are often not introduced to the family business because in an instance where the business becomes successful, the goodwill and accolades will be transferred to the husbands and his family. Meaning the wealth and the glory will be transferred to the wife’s family. Thus, a family will not introduce their female children to business because they fear that the business might be transferred to the spouse’s family. Rather, a male child will keep the business within the immediate family.

Male respondents are also motivated by other factor including non-pecuniary and internal motivations. For instance, R17 explained:

… … so, one of the reasons that made me, you know try to choose this part was to create an opportunity for people… … you know just to take a couple of people off the streets by giving them you know jobs and opportunities to make ends meet …R17

This is new especially as the present literature mainly posit that non-pecuniary motivators are mainly linked to women entrepreneurs only (see for instance: Manolova et al., 2012). Also, Dawson & Henley (2012) posit that social entrepreneurs and/or entrepreneurs who provide goods and services in the environmental/sustainability industry are primarily motivated by non-pecuniary factors, this research shows otherwise that R17 operates in the real estate sector and belongs to the male gender, states pecuniary reasons as his motivating factor though secondary to financial motivation.

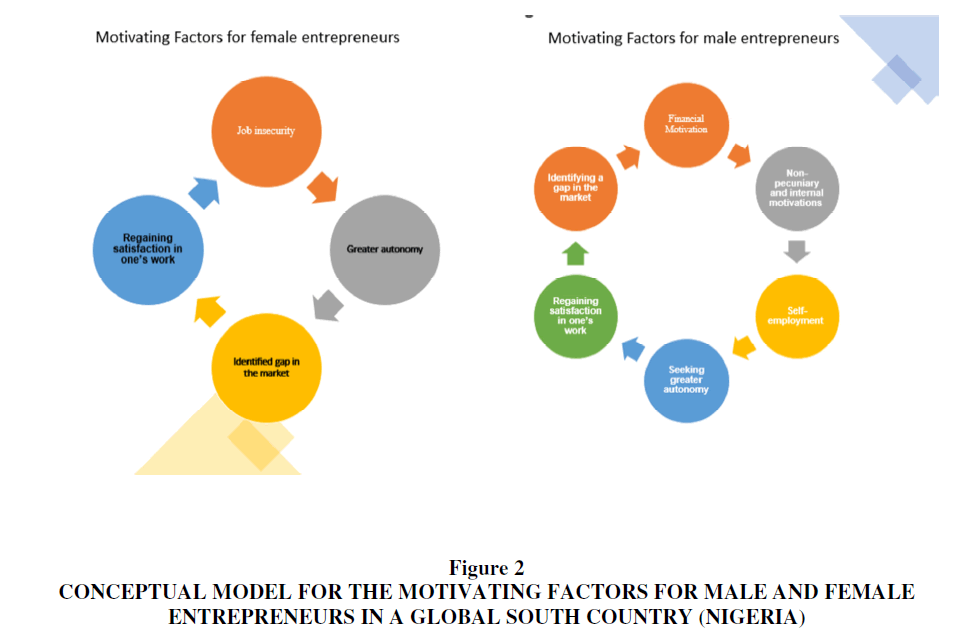

In summary, placing the motivating factors of male entrepreneurs' side by side with female entrepreneurs, this study can draw out some similarities and differences as seen in figure 2.

Figure 2 Conceptual Model for the Motivating Factors for Male and Female Entrepreneurs in a Global South Country (Nigeria)

The implication of this model is that female and male entrepreneurs are motivated into entrepreneurship due to the need to regain satisfaction in one’s work which shows a dissatisfaction at workplaces push individuals to choose entrepreneurship. This aligns with the findings of (Kitching & Woldie, 2004).

Conclusion

This study contributes to the ongoing discourse on the pull and push factors that influence the start of entrepreneurship and how this differs with their male counterparts in global south economies specifically in Nigeria. The novelty of this study lies in its focus on the widened gender inequality gap in entrepreneurship caused by the type of businesses run by female entrepreneurs, which can be traced down to the marginalization of women in the global south. This marginalization promotes women starting entrepreneurship in specific non-growth sectors, which hampers the achievement of UN SDG number 5 on gender equality and empowerment of women and girls. The study of women’s motivation for entrepreneurship has political and academic appeal. This study focused on a gender comparison approach to evaluate the extent marginalization has on the motivation for going into entrepreneurship and the resulting impact on the growth potentials of such businesses. This has practical implications as the findings of this study reiterate the importance of understudying entrepreneurship in context as the case of Nigeria shows a non-clear-cut selection of pull or push factors motivating women entrepreneurs because, in most cases, there are combined factors. This study also draws parallel with other female entrepreneurs in the global north using Ireland as a case in hand and reiterates the benefits of studying a phenomenon in context because while there are similarities, differences do abound. The study also has implications for policymakers as the development policy landscape is brimming with opportunities for women empowerment through entrepreneurship. Addressing these motivational actors, primarily social actors, will enhance the potential of achieving UN SDG number 5. As this paper has shown, differences between women’s and men’s motivation for entrepreneurship stems from the social construction of gender resulting from their marital/family structure and responsibilities, which is deeply rooted in the patriarchal nature of society.

References

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 30(5), 595-621.

Ajayi, B. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurial orientation and networking capabilities on the export performance of Nigerian agricultural SMEs. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 2(1), 1-23.

Amit, R., Muller, E. (1995). ‘Push’ and ‘pull’ entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship. 12(4), 64–80

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2022). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage.

Brush, C. G., & Cooper, S. Y. (2012). Female entrepreneurship and economic development: An international perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(1-2), 1-6.

Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (Eds.). (2007). The Sage handbook of grounded theory. Sage.

Carr, D. (2001). Two Paths to Self-Employment?. Working in Restructured Workplaces: Challenges and New Directions for the Sociology of Work, 23(1), 127.

Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: what do we still need to know?. Journal of small business management, 49(1), 9-26.

Cassia, L., De Massis, A., & Pizzurno, E. (2012). Strategic innovation and new product development in family firms: An empirically grounded theoretical framework. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 18(2), 198-232.

Charmaz, Kathy (2014).Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Choi, S. Y., Kim S-J. (2021). What Brings Female Professionals to Entrepreneurship? Exploring the Antecedents of Women’s Professional Entrepreneurship. Sustainability. 13(4),1765.

Corbin, Juliet & Strauss, Anselm (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SageCreswell, John (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Dawson, C., & Henley, A. (2012). “Push” versus “pull” entrepreneurship: an ambiguous distinction?. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 18(6), 697-719.

DeMartino, R., & Barbato, R. (2003). Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of business venturing, 18(6), 815-832.

Devine, T. J. (1994). Characteristics of self-employed women in the United States. Monthly Lab. Rev., 117, 20.

Dormekpor, E., 2015. Poverty and gender inequality in developing countries. Developing Country Studies, 5(10), pp.76-102.

Durojaye, E., & Adebanjo, A. (2014). Harmful cultural practices and gender equality in Nigeria. Gender and Behaviour, 12(1), 6169-6181.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management journal, 32(3), 543-576.

Eshiet, I. (2019). Sustainable Development Goal 3 and Maternal Health in Nigeria: Any Hope of Meeting the Target by 2030?. In Human Rights, Public Values, and Leadership in Healthcare Policy (pp. 247-271). IGI Global.

Fierman, Jaclyn (1990). "Why Women Still Don't Hit the Top," Eortune 122(3), 40-62.

Garba, A. S. (2011). Stumbling block for women entrepreneurship in Nigeria: How risk attitude and lack of capital mitigates their need for business expansion. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 36(3), 38-49.

Holton, J. A. (2008). Grounded theory as a general research methodology. The grounded theory review, 7(2), 67-93.

Huggins, R., Thompson, P., & Obschonka, M. (2018). Human behaviour and economic growth: A psychocultural perspective on local and regional development. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(6), 1269-1289.

Hughes, K. D. (2003). Pushed or pulled? Women's entry into self‐employment and small business ownership. Gender, work & organization, 10(4), 433-454.

Igwe, P. A., Amaugo, A. N., Ogundana, O. M., Egere, O. M., & Anigbo, J. A. (2019). Factors affecting the investment climate, SMEs productivity and entrepreneurship in Nigeria. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(1), 182-200.

Ihugba, O. A., Bankong, B., & Ebomuche, N. C. (2013). The impact of Nigeria microfinance banks on poverty reduction: Imo State experience. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(16), 97-114.

Irene, B., Marika, A., Giovanni, A., & Mario, C. (2016). Indicators and metrics for social business: a review of current approaches. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 1-24.

Itani, H., Sidani, Y. M., & Baalbaki, I. (2011). United Arab Emirates female entrepreneurs: motivations and frustrations. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 30(5), 409-424.

Jamali, D. (2009). Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries: A relational perspective. Gender in management: an international journal, 24(4), 232-251.

Jennings, J. E., & McDougald, M. S. (2007). Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Academy of management review, 32(3), 747-760.

Kandel, W., & Massey, D. S. (2002). The culture of Mexican migration: a theoretical and empirical analysis. Social Forces 80(3): 981-1004.

Kelle, Udo (2007). The development of categories: Different approaches in grounded theory. In Antony Bryant & Kathy Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp.191-213). London: Sage.

Kensbock, S., & Jennings, G. (2011). Pursuing: A grounded theory of tourism entrepreneurs' understanding and praxis of sustainable tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 16(5), 489-504.

Kirkwood, J. and Tootell, B., 2008. Is entrepreneurship the answer to achieving work–family balance?. Journal of management & organization, 14(3), pp.285-302.

Kirkwood, J., 2009. Motivational factors in a push‐pull theory of entrepreneurship. Gender in Management: An International Journal.

Kitching, B., & Woldie, A. (2004). Female Entrepreneurs in Transitional Economies: a comparative study of Businesswomen in Nigeria and China. In 4th Annual Hawaii International Conference on Business. 2004 Conference Proceedings. (pp. 1-19). Hawaii International Conference on Business.

Konrad, A. M., & Langton, N. (1991, August). Sex Differences In Job Preferences, Workplace Segregation, And Compensating Earning Differentials: The Case Of Stanford Mba's. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 1991, No. 1, pp. 368-372). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Kuada, J. (2009). Gender, social networks, and entrepreneurship in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 10(1), 85-103.

Kura, S.M. and Yero, B.U., 2013. An analysis of gender inequality and national gender policy in Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 4(1), pp.1-23.

Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Naffziger, D. W. (1997). An examination of owner's goals in sustaining entrepreneurship. Journal of small business management, 35(1), 24.

Loscocco, K., & Bird, S. R. (2012). Gendered paths: Why women lag behind men in small business success. Work and occupations, 39(2), 183-219.

Makama, G. A. (2013). Patriarchy and gender inequality in Nigeria: The way forward. European scientific journal, 9(17).

Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Shaver, K. G. (2012). One size does not fit all: Entrepreneurial expectancies and growth intentions of US women and men nascent entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(1-2), 7-27.

Manolova, T. S., Eunni, R. V., & Gyoshev, B. S. (2008). Institutional environments for entrepreneurship: Evidence from emerging economies in Eastern Europe. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 32(1), 203-218.

Marlow, S. (2002). Women and self-employment: a part of or apart from theoretical construct?. The international journal of entrepreneurship and innovation, 3(2), 83-91.

McClelland, E., Swail, J., Bell, J., & Ibbotson, P. (2005). Following the pathway of female entrepreneurs: A six‐country investigation. International journal of entrepreneurial behavior & research, 11(2), 84-107.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M., 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. sage.

Morris, M. H., & Lewis, P. S. (1995). The determinants of entrepreneurial activity: Implications for marketing. European journal of marketing, 29(7), 31-48.

Mukoro, A. S. (2014). Gender participation in university education in Nigeria: closing the gap. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, (23), 53-62.

National Bureau of Statistics, 2014. Statistical report on women and men in Nigeria.

Odozi, J. C. (2012). Socio economic gender inequality in Nigeria: A review of theory and measurements.

Ogundana, O. M., Simba, A., Dana, L. P., & Liguori, E. (2021). Women entrepreneurship in developing economies: A gender-based growth model. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(sup1), S42-S72.

Ojiakor, N. (1997). Empowering women for national development In Ngozi Ojiakor and G. C. Unachukwu (eds.) Nigeria socio-political development : Issues and problems, Publishers. Enugu: Jacobs Classic

Onoshakpor, C., James, I., Ibukun, T., & Irene, B. (2023). Gender Marginalization and Entrepreneurial Motivation in the Global South.

Onoshakpor, C., Cunningham, J., & Gammie, E. (2022). Female entrepreneurship in Nigeria and access to finance: a comparative study.

Parveen, M., Junaid, M., Saleem, M., Hina, S. M., & Ahmed, M. (2020). Analysis of push-pull motivation into women’s entrepreneurial experience in Pakistan: A narrative inquiry. Asian Women, 36(1), 91-112.

Patrick, C., Stephens, H., & Weinstein, A. (2016). Where are all the self-employed women? Push and pull factors influencing female labor market decisions. Small Business Economics, 46, 365-390.

Salaam, T. 2003. A Brief Analysis On The Situation Of Women In Nigeria Today, DSM

Schjoedt, L. and Shaver, K.G., 2007. Deciding on an entrepreneurial career: A test of the pull and push hypotheses using the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics data. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 31(5), pp.733-752.

Segal, G., Borgia, D., & Schoenfeld, J. (2005). The motivation to become an entrepreneur. International journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & research, 11(1), 42-57.

Shinnar, R. S., & Young, C. A. (2008). Hispanic immigrant entrepreneurs in the Las Vegas metropolitan area: motivations for entry into and outcomes of self‐employment. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(2), 242-262.

Thaddeus, E. (2012). Perspectives: Entrepreneurship development & growth of enterprises in Nigeria. Entrepreneurial practice review, 2(2), 31-35.

Tlaiss, H. A. (2015). Entrepreneurial motivations of women: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. International Small Business Journal, 33(5), 562-581.

Thurik, R., Verheul, I., Hessels, J., & van der Zwan, P. (2010). Factors Influencing the Entrepreneurial Engagement of Opportunity and Necessity Entrepreneurs. Eim Business And Policy Research.

Uhlaner, L., Thurik, A. R. (2007). Postmaterialism influencing total entrepreneurial activity across nations. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 17(2), 161–185.

UNDESA. 2019. World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420) (New York)

Verheul, I., Stel, A. V., & Thurik, R. (2006). Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrepreneurship and regional development, 18(2), 151-183.

Verheul, I., Thurik, R., Grilo, I., & Van der Zwan, P. (2012). Explaining preferences and actual involvement in self-employment: Gender and the entrepreneurial personality. Journal of economic psychology, 33(2), 325-341.

Winn, J. (2004). Entrepreneurship: Not an easy path to top management for women. Women in Management Review, 19(3), 143-153.

World Economic Forum. (2020). The global gender gap report. Geneva: WEF.

Yin, R.K., 1994. Discovering the future of the case study. Method in evaluation research. Evaluation practice, 15

Received: 25-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-23-14027; Editor assigned: 28-Aug-2023, Pre QC No. IJE-23-14027 (PQ); Reviewed: 11-Sep-2023, QC No. IJE-23-14027; Revised: 16-Sep-2023,, Manuscript No. IJE-23-14027(R); Published: 23-Sep-2023