Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 1

Entrepreneurial Marketing Drives MSME Sustainability? �?? Evidence from Indian MSMEs

Gururaj Phatak, Kirloskar Institute of Management

Pushpa Hongal, Karnatak University

Citation Information: Phatak, G. & Hongal, P. (2023). Entrepreneurial marketing drives msme sustainability? – evidence from indian msmes. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 27(1), 1-14.

Abstract

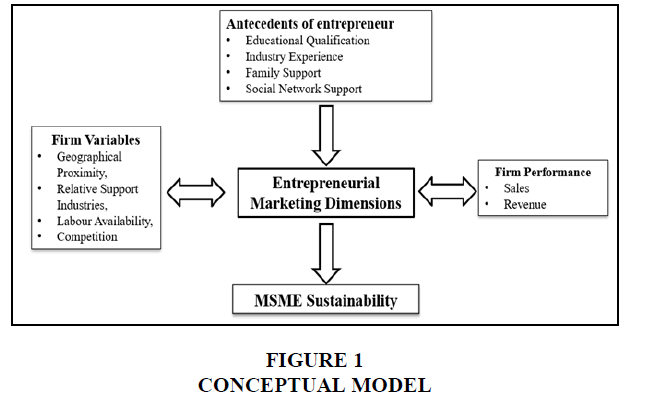

Entrepreneurs must unlearn old marketing ideas and replace them with fresh, innovative thinking and actions, such as entrepreneurial marketing, when traditional marketing approaches are inadequate for small and medium businesses (EM). A Conceptual Framework is developed based on EM dimensions on Micro, Small and Medium-sized firms (MSMEs), highlighting their sustainability in this research related to Indian Context.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Marketing, Entrepreneurial Marketing, MSMEs, Sustainability.

Introduction

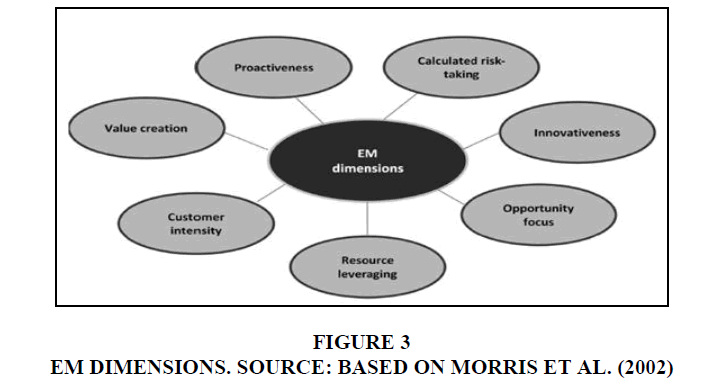

Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) was established as a concept in 1982, and various researchers have attempted to define it since then Hills & Hultman (2011); Morris et al. (2002); Stokes (2000). The term is frequently connected with marketing activities in small businesses with limited resources, which must rely on unconventional and creative strategies. It is also used to describe entrepreneurs' unexpected, nonlinear, and creative marketing strategies Morris et al. (2002). EM is defined as an organisational orientation with seven underlying dimensions: proactiveness, opportunity focus, calculated risk-taking, innovativeness, customer intensity, resource leveraging, and value creation Hisrich (1992); Morris et al. (2002); thus, EM can be viewed as a new paradigm that integrates critical aspects of marketing and entrepreneurship into a comprehensive concept where marketing becomes a process used by firms to act empathetically Collinson (2002). Entrepreneurs and managers must relearn classic management principles and replace them with new inventive thinking and actions, such as EM, in the present business climate, characterised by growing dynamics, turbulence, and competitiveness Hills et al. (2010). At the junction of the two most important fields of business administration, this is seen as a promising and expanding study sector Hills et al. (2010). Guerrilla marketing, ambush marketing, buzz marketing, and viral marketing are the most well-known styles of entrepreneurial marketing Hisrich (1992). These types are considered very useful for SMEs because they are low cost and innovative forms of doing marketing Abdalhadi & Narci (2021).

Numerous academics have taken an interest in entrepreneurial marketing. According to Morris et al. (2002), this relatively new topic has many study prospects. Existing research has discovered that EM improves performance Becherer et al. (2012); Hacioglu et al. (2012); Hamali (2015); Hamali et al. (2016); Morrish & Deacon (2011); Mugambi & Karugu, 2017). The majority of the research is theoretical and historical in nature. Toghraee, Rezvani, Mobaraki, and Farsi (2017) conducted an extensive review of entrepreneurial marketing literature and discovered a significant heterogeneity of approaches among studies, indicating a challenge at the intersection of marketing and entrepreneurship; they believe there are too many heterogeneous samples, too many remote questionnaire studies with single respondents, and too few qualitative studies, and one of their recommendations is to conduct more qualitative studies Azen & Traxel (2009).

The shortcoming is that there are minor empirical investigations on EM. Furthermore, little, if anything, is known about the EM component and its impact on SMEs' performance in Kosovo. There are significant gaps in the literature; no widely agreed definition of EM, or EM dimensions and practises, exists Li et al. (2019). This research aims to learn more about how entrepreneurial marketing factors affect SME performance Crawford (2006). This research will look at how seven dimensions of EM proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, innovativeness, opportunity focus, resource leveraging, customer intensity, and value creation Morris et al. (2002) are linked to performance variables like growth, efficiency, profit, reputation, and owners' personal goals. We focus on discovering correlations between EM characteristics and their impact on the performance of SMEs in Kosovo to determine the impact of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions on the overall performance of SMEs.

The scope of this study is to focus on the following: 1) although many authors have developed a different number of dimensions of EM, this study will be based only on the seven EM dimensions proposed by Morris et al. (2002) the study will focus only on SMEs in Kosovo; and 3) since there is no agreed performance measurement among researchers (Murphy, Trailer, & Hill, 1996), and based on the recommendations of many researchers Evans (2005); Murphy & Callaway (2004); Panigyrakis & Theodoridis (2007); Randolph, Sapienza, & Watson, 1991; Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1986) that for the measurement of the performance, both financial and non-financial measures should be used, such as growth, efficiency, profit, reputation and owners' personal goals as a measure of overall SME performance.

This study aims to fill a gap in the literature by conducting the first study to correlate the entrepreneurial marketing characteristics with the performance of SMEs in Kosovo. Furthermore, because quantitative studies are still few, this study will fill a vacuum in the literature. The findings may also be helpful to policymakers who recognise the importance of SMEs in the economy and, consequently, may utilise the study's findings to develop better policies to promote SMEs. Understanding and implementing some of the principles of entrepreneurial marketing discussed in this study may be beneficial to business owners. Finally, this research may pique the attention of other academics and researchers in furthering this topic of study Table 1.

| Table 1 Definitions Of Entrepreneurial Marketing |

||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Definition | Author |

| 2000 | “EM is marketing carried out by entrepreneurs or owner-managers of entrepreneurial ventures.” | Stokes (2000), p. 2) |

| 2002 | “Proactive identification and exploitation of opportunities for acquiring and retaining profitable customers through innovative approaches to the risk management, resource leveraging and value creation.” | Morris et al. (2002), p. 4) |

| 2002 | “Marketing of small firms growing through entrepreneurship” | Bjerke and Hultman (2002, p.15) |

| 2006 | “EM is the overlapping aspects between entrepreneurship and marketing; therefore, it is the behavior shown by any individual and/or organization that attempts to establish and promote market ideas, while developing new ones in order to create value” | Bäckbrö & Nyström (2006, p.13) |

| 2009 | “A particular type of marketing that is innovative, risky, proactive, focuses on opportunities and can be performed without resources currently controlled.” | Kraus et al. (2012), p. 30) |

| 2011 | “EM is a spirit, an orientation as well as a process of passionately pursuing opportunities and launching and growing ventures that create perceived customer value through relationships by employing innovativeness, creativity, selling, market immersion, networking and flexibility.” | Hills & Hultman (2011), p. 6) |

| 2012 | “EM is a set of processes of creating, communicating and delivering value, guided by effectual logic and used a highly uncertain business environment.” | Ionita (2012, p. 147) |

| 2012 | “The marketing processes of firms pursuing opportunities in uncertain market circumstances often under constrained resource conditions.” | Becherer et al. (2012), p. 7) |

| 2016 | “EM is a combination of innovative, proactive, and risk-taking activities that create, communicate, and deliver value to and by customers, entrepreneurs, marketers, their partners, and society at large.” |

Whalen et al. (2016, p. 3) |

Literature Review

The Concept of Entrepreneurial Marketing

Entrepreneurial marketing has allowed for the creation of many research streams, resulting in various perspectives and definitions of the EM idea. Studies on SME marketing were presented as one core study stream. Because small businesses are not mini-versions of significant businesses (Storey, 1989), an alternative marketing strategy was required to apply to small businesses. Another branch of entrepreneurial marketing study focuses on the entrepreneur's behaviour Hills & Hultman (2011).

This line of study has contributed to the entrepreneurial marketing environment by claiming that traditional marketing as described in the literature may not be entirely applicable to small and medium-sized businesses Kraus et al. (2012). The EM has been highlighted as a more viable option for explaining the marketing of small businesses with limited resources driven by entrepreneurial activity. As a result, the focus of study has shifted from minor to significant firms (Ionit, 2012). Entrepreneurial marketing, according to studies, may be used by any business, regardless of size Hisrich (1992); Kraus et al. (2012); Whalen et al., 2016).

The emergence of several EM research streams has led to numerous attempts by various researchers to define the idea of EM. As a result, many definitions exist, ranging from those that explicitly refer to marketing in small businesses (Hill & Wright, 2000), those that make no distinction between company size or age (Bäckbrö & Nyström, 2006; Kraus et al. (2012); Morris et al. (2002), and those that emphasise aspects of EM such as value creation (Bäckbrö & Nyström, 2006; Whalen et al., 2016) and innovativeness (Bäckb All EM definitions, however, have one thing in common: they all include aspects from both marketing and entrepreneurship.

Ionit (2012) describes EM as "proactive discovery and exploitation of possibilities for attracting and maintaining lucrative consumers through creative methods to risk management, resource leveraging, and value creation." Morris and colleagues Morris et al. (2002), p. 4) Table 1 lists the alternative definitions of EM often encountered in the literature in chronological order.

Given that the discipline of EM was born at the crossroads of entrepreneurship and marketing, neither of which has a widely acknowledged definition (Stokes & Wilson, 2009), and given the diversity of both areas, it is challenging to come up with a conventional and globally accepted definition of EM Kraus et al. (2012).

The Need For Entrepreneurial Marketing

Marketing scholars have called traditional marketing into question, who believe that a new marketing paradigm is required Webster (1992); Day & Montgomery, 1999; Sheth & Parvatiyar, 1995; Pels, 2015; Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Numerous empirical research has shown that standard marketing principles do not encompass all marketing tactics. For example, Hultman & Shaw (2003) discovered that service organisations participate in a variety of activities that are not covered by the typical marketing mix notion. These efforts are connected to building a reputation through referrals, goodwill, word-of-mouth, and long-term human relationships. According to Constantinides (2006), the traditional marketing mix approach lacks consumer orientation and customer interaction.

Another reason for the need for a new marketing paradigm is that today's business climate has become extremely difficult, particularly for small and medium businesses. Increased risk, uncertainty, turmoil, change, and contradiction define this competitive environment. In a global economy where customers are getting more demanding, these qualities significantly influence marketing Hills et al. (2008). According to Day & Montgomery (1999), the connected knowledge economy, globalisation and convergence, fragmenting and frictionless markets, demanding customers and their improved behaviour, and adaptive organisations are five changes that are critical for the marketing field to move in a new direction.

Marketing is one of the essential variables impacting a company's performance Soriano (2003). As a result, academics propose several new marketing strategies to supplement traditional marketing methods. Globalization has resulted in specific changes to traditional marketing, resulting in new non-traditional marketing formats (McKenna, 1991). As a result of these changes in the corporate environment, EM has developed a new marketing paradigm that assists businesses in rethinking their marketing strategies. EM can assist businesses in surviving and adapting to the changes highlighted by Day & Montgomery (1999).

The most significant need for EM is evidently in a setting marked by volatility, when standard marketing tactics are no longer appropriate Collinson & Shaw (2001); Morris et al. (2002). Because today's market has these features, EM implementation would be helpful and required for most enterprises Morris et al. (2002). It is worth noting that EM may be used in various ways at different stages of the marketing process Morris et al. (2002).

Marketing-Entrepreneurship Interface

Marketing is one of the oldest and most researched business disciplines, but entrepreneurship is one of the newest and fastest-growing industries Hoy (2008). Understanding the concepts "marketing" and "entrepreneurship" individually is the most straightforward approach to grasp the notion of "entrepreneurial marketing."

Entrepreneurship comes from the French word entreprendre, which means "to take on." Even though the topic of entrepreneurship has been thoroughly explored and several attempts to develop a widely acknowledged definition, there is still no universally agreed definition Hisrich (1992). Entrepreneurship is described as an individual's creative and risk-taking endeavour to make a profit in a new enterprise (Morris & Paul, 1987). According to Aldrich & Waldinger (1990), Entrepreneurship may be defined as the use of resources in novel ways to generate something worthwhile. According to Gartner (1988), Entrepreneurship is the process of starting a business. According to Ramadani, Rexhepi, Grguri-Rashiti, Ibraimi, and Dana (2014), entrepreneurship is a process of seeking out new opportunities in uncertain and dangerous situations by effectively and efficiently merging production components in order to create profit and company growth. According to Morris et al. (2002), entrepreneurship is a management style generally linked with proactive, risk-taking, and inventive techniques rather than a business function.

On the other hand, marketing is described as "the activity, collection of institutions, and procedures for producing, communicating, delivering, and exchanging value-added solutions for consumers, clients, partners, and society at large" (AMA, 2008). According to Zikmund and D'Amico (2002), any marketing definition should comprise five elements: two or more entities, something that each entity gives up, something that each entity receives, a level of communication between the entities, and a means to complete the exchange. According to Morris, Schindehutte, and LaForge (2001), most marketing definitions group marketing activities into four categories: product, location, pricing, and promotion, sometimes known as the marketing mix or 4Ps.

Entrepreneurs should make effective use of the marketing function to steer their enterprises in the right direction Hisrich (1992). The phrase "entrepreneurial marketing" is frequently used to describe marketing operations in small businesses with limited resources that must rely on unconventional and inventive strategies. Entrepreneurs' unplanned, nonlinear, and proactive marketing efforts are sometimes called "unplanned, nonlinear, and visionary marketing" Morris et al. (2002).

When you look at the definitions of marketing and entrepreneurship, you will see that they have at least three things in common. First and foremost, both industries stress the need for a management process. Second, both categories' definitions are premium on unique combinations, marketing mix factors, and resources. Third, both areas' definitions include value production Morris et al. (2001).

Until recently, marketing and entrepreneurship were two distinct areas that progressed independently of one another Hills & Hultman (2011). Miles (2014). As a result, entrepreneurial marketing (EM) is a relatively new theory that emerged nearly 40 years ago as the interface between those two disciplines Hills et al. (2010), when scholars began to agree that entrepreneurship and innovation play a significant role in marketing, as well as that marketing, plays a significant role in entrepreneurship Soriano (2005); Stokes (2000).

Numerous scholars have recognised the relationship between entrepreneurship and marketing during the last few decades, understanding that entrepreneurs are involved in many critical activities to marketing theory Collinson & Shaw (2001). Murray and Tyebjee were the first to integrate marketing and entrepreneurship in the 1980s Hills & Hultman (2011). They looked at the connection between marketing and entrepreneurship and argued that Entrepreneurial Marketing is the meeting point of these two disciplines Miles & Darroch (2006). Gardner (1990) also defined the intersection between marketing and entrepreneurship as "the region where innovation is brought to market" Gardner (1990), p. 1). Many academics have noted commonalities between the two areas and proposed complementing one other. According to Hills and LaForge (1992), marketing and entrepreneurship are comparable because both disciplines have a strong interaction with the environment, and both require the assumption of risk and uncertainty. Carson and Coviello (1996) note that both fields emphasise behavioural processes and innovation, that they share a common underlying concept of market and customer, and are both based on multidisciplinary academic foundations. Furthermore, both professions prioritise consumers Hills et al. (2010); Hisrich (1992), and they are both change-oriented, opportunistic in character, and inventive in their management approaches Collinson & Shaw (2001). Their primary goal is to create customer value Hills et al. (2010). As a result, it is proposed that the intersection of marketing and entrepreneurship might assist entrepreneurs in identifying potential possibilities, dealing with change, and expanding their inventive talents Collinson (2002).

When studying the marketing/entrepreneurship interface, Morris et al. (2002) suggests two subject investigation areas Gliem & Gliem (2003). The function of marketing in entrepreneurship may be described as the first area, while the role of entrepreneurship in marketing can be characterised as the second region of the interface. The first field of research is the application of marketing techniques, concepts, and theories to aid in the formation of new businesses. The second area of inquiry illustrates how entrepreneurial habits and attitudes may be used to marketing programme creation.

Because the fields of marketing and entrepreneurship are so similar, research methods and techniques appropriate for marketing may be utilised and adapted to the subject of entrepreneurship and vice versa (Carson & Coviello, 1996). When researchers began to emphasise the complementary roles of marketing and entrepreneurship in a firm, particularly in SMEs Collinson (2002); Collinson & Shaw (2001); Hills et al. (2008); Hills et al. (2010); Hisrich (1992), the interface between marketing and entrepreneurship became a rich focus for research Hills et al. (2008).

Entrepreneurial Marketing Strategies

Hills & Hultman (2011) use Schumpeter and Kirzner to build EM tactics. Value logic (Schumpeterian dimension) and opportunity are the two dimensions that their approach is built on (Kirznerian dimension). They claim that EM is a value creation process and that value creation is the primary goal of both marketing and entrepreneurship. Customer value is a collaborative process because neither the producer nor the buyer can create it alone. That market will be lost if the seller does not deliver value to the customer. Customers must identify the value in an exchange transaction to keep in contact with the vendor. The value logic describes what buyers get in exchange for their money and how the seller benefits from giving the goods. Customers will repeat their transactions as long as the vendor meets their expectations, and the seller will keep its market position. When the current value is modified by adding innovation that gives more excellent perceived consumer value, the Schumpeterian dimension is referred to as this. The Kirznerian dimension refers to the entrepreneur's capacity to notice possibilities that others do not. Four techniques may emerge based on these two aspects Figure 1.

Figure 2. Entrepreneurial marketing strategies. Source: Based on Hills & Hultman (2011).

A classic marketing strategy is when a seller creates market dominance and establishes perceived consumer value for the business to be profitable. This might be employed when businesses keep their present marketplaces while exchanging the same consumer value. The goal of the Kirznerian EM approach is to find fresh, untapped possibilities. When an entrepreneur employs this method, he or she identifies new markets while maintaining the same business models and giving the same value reasoning in each one. The Schumpeterian EM approach is used when entrepreneurs modify the value logic by constantly researching new inventions and bringing novelties that impact customers' perceived value in the existing market. When customer value expectations are exceeded by giving higher value to new markets through purposeful and continual innovation to upset the existing value balance, Schumpeterian EM strategy II is used. Entrepreneurs may choose to act based on the information presented strategies mentioned above, or they may make combinations of all the types Hills & Hultman (2011).

Entrepreneurial Dimensions

Different academics have utilised different classifications to investigate the firm's EM behaviour in previous years. These classifications vary based on the study's setting, and they range not just in substance but also in the number of dimensions they employ. Even though EM behaviours have been extensively studied, there is no consensus on the number of aspects that underpin EM behaviours (Kilenthong, Hills, & Hultman, 2015).

Prior research has identified several characteristics of EM behaviours, including a focus on innovation Hills & Hultman (2011); Whalen et al., 2016), calculated risk-taking Hills & Hultman (2011), focus on opportunity recognition (Hills & Singh, 1998), flexible approaches to markets (Shaw, 2004), and focus on innovation Hills & Hultman (2011). Hills & Hultman (2013); Morrish & Deacon (2011); Whalen et al., 2016). Because different scholars have given different numbers of characteristics, there have been several debates in the literature about the nature of the construct of EM, its dimensionality Hills & Hultman (2011); Morris et al. (2002), the interdependence of the dimensions (Kilenthong, Hultman, & Hills, 2016), and the nature of the dimensions (Kilenthong, Hultman, & Hills, 2016). Hills & Hultman (2011).

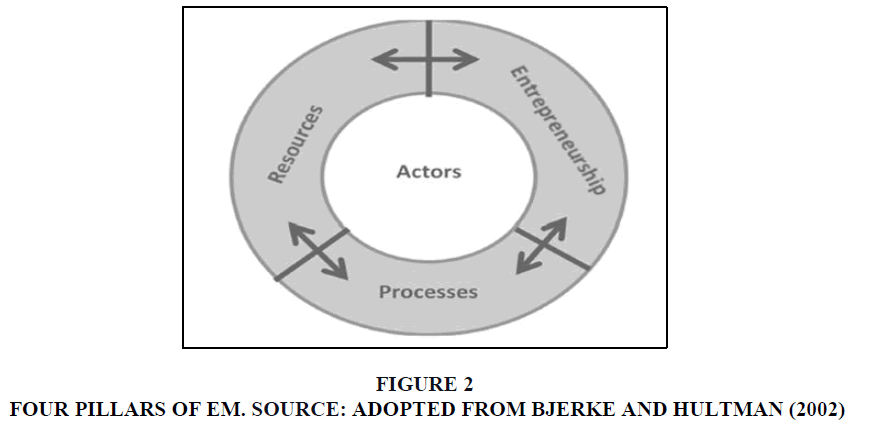

Entrepreneurial marketing has four pillars, according to Bjerke and Hultman (2002): entrepreneurship, processes, actors, and resources (Fig. 2). The pillar of entrepreneurship emphasises proactiveness, opportunity hunting, and innovation, and it relates to why and how opportunities may be identified and implemented in the development of consumer value. The ways and actions by which a company produces customer value are referred to as processes. Actors play entrepreneurs who operate the processes and provide value to customers. The inputs required to develop customer value are referred to as resources. Firms can either own resources or develop them via collaboration with external parties (Bjerke & Hultman, 2002) Figure 2.

Hills & Hultman (2011) discovered numerous marketing behaviours distinctive of entrepreneurial enterprises in research that looked into how entrepreneurial firms participate in their marketing strategies Jabareen (2009). Non-implementation of the marketing mix concept, a focus on high-quality products, the use of gut feelings and intuitive decision making, the use of networks and relationships in marketing, a lack of commitment to formal market research, and the influence of personal goals on the firm's marketing goal are all examples of these behaviours. Similar studies have also documented this behaviour Hills & Hultman (2011); Stokes (2000).

Shaw (2004) describes EM activities in the context of social entrepreneurship using four themes: opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial endeavour, entrepreneurial organisational culture, and networks and networking. Gruber (2004) elaborates on marketing in small and young businesses by identifying three essential dimensions: newness, modest size, and uncertainty and turbulence. In addition, Jones and Rowley (2010) developed the EMICO framework. Market orientation (MO), entrepreneurial orientation (EO), innovation orientation (IO), and customer and sales orientation (CO/SO) literature were used to create this framework, which comprises fifteen components. Growth orientation, opportunity orientation, value creation through networks, total customer focus, informal market analysis, and proximity to the market are the six elements of EM behaviour outlined by Kilenthong et al. (2015). Morris et al. (2002) described proactiveness, measured risk-taking, innovativeness, opportunity focus, resource leveraging, customer intensity, and value generation as seven pillars of EM (Fig. 3). The first four categories are based on research on entrepreneurial orientation. On the other hand, the last two aspects are taken from marketing orientation literature. A fifth feature, resource leveraging, is emphasised heavily in guerrilla marketing and frequently appears in entrepreneurial literature Franco et al. (2014).

Given the lack of agreement among researchers on the EM dimensions, this paper will employ the seven dimensions given by Morris et al. (2002) based on current literature and comparable conceptualizations of EM (2002). Proactive marketers do not view the external world as a collection of conditions to Hair et al. (2011) which the firm can merely adjust. Proactivity is a response to opportunities that allow a corporation to anticipate changes in the market and be among the first to respond to them (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001). Measured risk-taking refers to a company's capacity to utilize calculated steps to limit the risk of pursuing an opportunity Becherer et al. (2012). Calculated risk-taking is being willing to pursue possibilities that have a reasonable potential of resulting in losses or a substantial performance gap Morris et al. (2002) Figure 3.

Figure 3: Em Dimensions. Source: Based on Morris et al. (2002).

Innovativeness is a significant factor in a company's success Calantone et al. (2002); Danneels, Kleinschmidt, & Cooper, 2000; Read, 2000; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). The capacity of a company to sustain a flow of fresh ideas that may be translated into new goods, services, technology, or markets is characterised as innovation Morris et al. (2002); Otieno et al. (2012). Focusing on innovation may help businesses go beyond recognising opportunities by repurposing new or existing resources Morris et al. (2002). Unnoticed market positions with long-term profit potential are referred to as opportunity focus.

Today, opportunity recognition plays a critical role in entrepreneurship theory and entrepreneurship research Hills et al. (2010). "Dedication to opportunities" and "opportunity detection abilities" are two characteristics that set EM distinct from traditional marketing Hills et al. (2008). The firm's skill may be observed in the opportunity selection that affects success Becherer, Haynes, & Helms, 2008. A company's capacity to access resources to achieve more with less is referred to as resource leveraging Becherer et al. (2012). Entrepreneurial marketers, according to Morris et al. (2002), can leverage resources in a variety of ways, including recognising resources not seen by others, using others' resources to complete own purpose, complementing resources with one another to increase value, using specific resources to find other resources, and extending resources much further than others have done in the past. Customer intensity is viewed as a factor contributing to the company's fundamental values of customer passion and staff recognition of products and services Hisrich (1992). Customer intensity is an essential aspect of EM and a crucial component of the market orientation concept (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990). Marketers have to uncover untapped sources of consumer value and to build exclusive combinations of sources to produce value, according to the definition of value creation Morris et al. (2002).

Entrepreneurial Marketing and Sme Performance

Entrepreneurial marketing is a new subject of study that has piqued the interest of several academics. However, although there are several results in a literature search on this issue, only a few publications have looked into the influence of entrepreneurial marketing on SME performance and growth. Morris et al. (2002) defined the seven elements of entrepreneurial marketing, although their research was grounded on theoretical ideas. The seven EM dimensions established by Morris et al. (2002) have been used in several investigations listed below.

In their research, miles & Darroch (2006) have explored how large firms might leverage entrepreneurial marketing processes to gain and renew competitive advantage. Their study has applied past research on entrepreneurial marketing and entrepreneurship with examples from a long-term case study of firms in New Zealand, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States in order to illustrate how entrepreneurial marketing processes can be strategically employed by large firms to create or discover, assess, and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities more effectively and efficiently. They adopted risk management, pro-activeness, opportunity-driven, innovation, customer intensity, value creation, and resource leveraging as the explanatory variables that contributed to this competitive advantage. Their findings gave insights into how large firms leverage entrepreneurial marketing processes to grow.

Kurgun, Bagiran, Ozeren, and Maral (2011) performed a qualitative study among boutique hotels in Izmir, Turkey, to see if their marketing strategies were consistent with entrepreneurial marketing strategies. They used the seven aspects of EM to conduct semi-structured interviews. Entrepreneurial marketing principles have been implemented, according to them, and are critical for boutique hotels.

With a sample of 174 SMEs, Becherer et al. (2012) investigated the link between seven entrepreneurial marketing aspects and SMEs' qualitative and quantitative outcomes. They discovered that entrepreneurial marketing features influenced the outcome variables using stepwise regression. The three success variables emerged as a group using factor analysis. According to the findings of this study, entrepreneurial marketing aspects appear to have a direct and positive effect on outcomes connected to owner-operated SMEs.

Similarly, Hacioglu et al. (2012) investigated the influence of EM on innovative performance in the Turkish manufacturing industry using a sample size of 560 SMEs. The results demonstrated that the entrepreneurial marketing characteristics of proactivity, innovation, customer intensity, and resource leveraging are all positively associated with innovative success.

The Morris et al. (2002) model has also been used by Morrish et al. (2010). Their study's goal was to seek evidence of entrepreneurial marketing tactics. They performed the qualitative study using two cases: 42 Below, a New Zealand vodka maker, and Penderyn Distillery, a Welsh whiskey distillery. In both situations, they discovered that EM worked well.

Rezvani and Khazaei (2014) looked at how entrepreneurial marketing is used differently depending on the age and size of higher education institutions. The findings revealed that the utilisation of each entrepreneurial marketing feature varies depending on the age and size of the organisation.

Hamali (2015) examined the influence of EM on small company performance in Bandung, Indonesia, focusing on the small garment sector. He researched a group of 90 people. He discovered that EM aspects like proactiveness, resource leveraging, value creation, and customer intensity have a substantial and favourable influence on business success after completing a multiple linear regression.

With a sample of 200 small businesses, Hamali et al. (2016) investigated the influence of entrepreneurial marketing on innovation and its impact on marketing performance and financial performance of the wearing apparel small industries in West Java, Indonesia. The findings imply that entrepreneurial marketing impacts innovation, which, in turn, has an impact on the business success of West Java's small garment firms.

In Asaba, Delta State, Nigeria, Olannye and Edward (2016) evaluated the impact of entrepreneurial marketing on the performance of fast-food businesses. They used a survey study design technique to interview 160 employees and consumers of a few fast-food businesses in Asaba, Delta State. The study tool was a 20-item validated structured questionnaire. As essential analytical methods, correlation and multiple regression analysis were utilised. According to the study's findings, entrepreneurial entrepreneurial innovation, and entrepreneurial opportunity recognition as markers of entrepreneurial marketing had a considerable beneficial influence on competitive advantage.

Mugambi and Karugu (2017) examined the influence of entrepreneurial marketing on the success of real estate firms in the instance of Option Limited in a more recent study. The study's goal was to determine how strategy orientation, innovation orientation, market orientation, and resource leveraging impact Optiven's success as a real estate company in Nairobi, Kenya. The study's findings demonstrated a strong association between strategy orientation, market orientation, innovation orientation, and resource leveraging on the performance of Option Limited, a real-world company.

Rashad (2018) performed the most recent study in this field, which looked at the influence of entrepreneurial marketing aspects on organisational performance in Saudi SMEs. The data for the study was gathered from a sample of 50 managers and owners of SMEs in Jeddah using survey questions sent through e-mail and an online questionnaire. Dimensions of EM were exhibited within the sample of SMEs in Jeddah, according to factor analysis results. According to regression analysis results, the opportunity targeted, a calculated risk taken, and value generation elements of EM are all positively associated with success.

This research contributed significantly to our knowledge of the EM dimensions and their application and measurement in empirical investigations. They all agree that EM characteristics are critical for SME success, even though the relevance of these dimensions varies depending on the nation and environment, implying that the dimensions that affect SME performance in one country may not affect SME performance in another. The rationale for this may be found in Morris et al. (2002) theoretical model, which claims that external and internal environmental factors directly influence the organization's marketing approach, which in turn has an impact on the financial and non-financial outcomes.

According to Morris et al. (2002), entrepreneurial marketing has several research potentials. He claims that a deeper understanding of his seven dimensions is required. Even if there has been progressed, there is still more to be done in the future on the EM, its drivers, manifestations, and links with performance (Toghraee et al., 2017). Toghraee et al. (2017) conducted a comprehensive analysis of the literature on entrepreneurial marketing and discovered significant variation in methods among research, indicating that there is a difficulty at the confluence of marketing and entrepreneurship.

Sustainability in MSME

India's economy is characterised by a significant number of small businesses with low levels of capital investment. Even though they are less efficient and do not always conform to certain international quality and governance requirements, these businesses generate significant production and jobs. Despite several hurdles and disadvantages, the Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprise (MSME) sector of the Indian economy has evolved as a vibrant and active sector. During the pre-liberalisation era, the government provided many protections and incentives to small businesses; many items were allocated for exclusive manufacturing in Small Scale Industries. The goal was to protect and promote small business owners who are more likely to use labour-intensive methods with low capital and locally available resources, thereby creating jobs in small towns and rural areas, preventing migration to large cities and industrial regions, contributing to balanced development, and achieving a variety of other economic goals.

MSMEs must become good corporate citizens at a period when India is on the verge of fulfilling its promise of becoming one of the world's economic powers. As a result, it is critical for MSMEs to focus on nine sustainability principles (Furman, 2009): Ethics, Governance, Transparency, Business Relationships, Financial Return, Community Involvement, Product and Service Values, Employment Practices, and Environmental Protection.

Sustainability has been defined and interpreted in several ways by various specialists. The Brundtland Commission (1987) defines sustainability as "meeting current demands without jeopardising future generations' ability to fulfil their own." According to Hogevold and Svensson (2012), sustainability is "a company's complete effort—including its demand and supply chain networks—to lessen the influence on the earth's life and ecosystem." Marc Epstein (2008) explains how business sustainability may be achieved through harnessing processes rather than by consuming in his book' Making Sustainability Work.

Sustainable development is mentioned in the Government of India's Economic Survey for 2013–2014 as a necessity for attaining intergenerational justice and a public benefit with a significant global component. It states that India has addressed sustainability challenges in its growth route but that its efforts are limited since numerous requirements compete for a limited number of resources. It states that all countries' economic and social development goals must be articulated in terms of sustainability and that current and future consumption balances within nations must be viewed in connection to past consumption patterns. Appropriate legislation has been implemented in India to promote sustainable production practices such as forest and ecosystem protection, waste management, and pollution control. The 'Swachh Bharat Mission,' which was just established, is likewise aimed at guaranteeing hygiene, waste management, and sanitation across the country. Joshi and Kurulkar (2004) emphasised the importance of other players in 'greening the economy.'

According to Mohammed et al. (2012), there is a compelling case for innovative practises in the MSMEs sector, contributing to GDP. According to the findings of this study, MSMEs' performance in Nigeria is anticipated to improve as they develop their ability to mimic major enterprises by taking advantage of government-provided growth possibilities. Furthermore, MSMEs are more likely to report their entry into new markets, more significant market share, and enhanced production and innovative service flexibility..

Kiraka et al. (2013) investigated the development and innovation of MSMEs in Kenya by evaluating the Women Enterprise Fund's (WEF) performance on these aspects. In the post-loan period, the most typical type of innovation was modifying or adding new items. On the other hand, women-owned businesses were less likely to innovate in terms of services, markets, and raw material sources. Furthermore, the socioeconomic characteristics of WEF loan customers were nearly consistent across geographic regions, borrowing streams (CWES, FI), and age categories. According to the study, there was a minimal indication of significant variations in growth and innovation across businesses across these characteristics.

Gorze-(2013) Mitka's research aimed to find risk detection tools in Polish SMEs. Previous experience, documentation evaluation, and brainstorming were practical risk detection approaches in the study. MSMEs, according to the researcher, have difficulty with this issue. It might be due to a lack of understanding, utility, or application possibilities.

Pandya (2013) emphasised the importance of sustainability for businesses. According to the survey, it provides private companies with a true competitive edge and green credentials for others. It also discusses the different advantages of implementing sustainability initiatives for SMEs. The ramifications of failing to include sustainability in any SME's strategy and operations have been explored.

Lee (2009) investigated the process of green management adoption in small and medium-sized businesses. SMEs may become greener by implementing strategic and organizational improvements, according to the study. Organizational structure, innovative capabilities, human resources, cost savings, and competitive advantage may all affect organizational transformation for greener management.

In response to the essential need for cleaner energy technology, Abdeen (2007) examined the possibilities for quality, cost, and energy-efficient integrated systems in the stationary and portable power markets. Similarly, existing and future patterns of energy usage and concerns connected to renewable energies, the environment, and sustainable development are analysed from both current and future viewpoints. It was stated that energy consumption reductions might be achieved through reducing energy demand, using energy more wisely, recovering heat, and utilising more green energy sources.

Enno (2006) investigated why certain SMEs are hesitant to adopt sustainable environmental measures while others are quick. According to the study, the most crucial reason these fast-growing SMEs invest in environmental measures is to boost their employees' motivation and performance. This explanation links 'planet' and 'people' but does not include 'profit,' which brings the classic sustainability circle. The study suggests that SMEs' attitudes toward sustainability should be explored in a different approach than has previously been done. The environment should be considered not only as a direct but also as an indirect component.

Bharadi (2014) investigated the rural development and long-term viability of India's micro, small, and medium companies. According to the findings, the SME sector is a breeding ground for entrepreneurship, typically fueled by individual ingenuity and innovation. It is the Indian rural economy's most neglected and unorganised sector.

The paper critically discusses the role of various stakeholders as of now and its socio-economic and environmental consequences for the region and the economy of Gujarat. Joshi and Kurulkar (2004) emphasised sustainable industrial development and stated that chemical and chemical products group industries in the region are highly polluting. Based on the conclusions, the policy implications for the greening of these industrial estates and the ‘Golden Corridor’ are being suggested.

From the perspective of Indian MSMEs, Rana and Dhrubes (2013) sought to empirically determine which aspects are most crucial in the ERP adoption process. Researchers discovered significant issues with ERP system deployment, leading to ideas for industry-specific improvement solutions. If organisations execute appropriate improvement initiatives, ERP system effectiveness and service quality may be improved. The study gave limited support for explaining failure during Enterprise Information System implementation.

According to Sonia and Rajeev (2014), small industries play a critical role in Punjab's export, promotion, resource use, employment, and investment and contribute to the country's GDP ratio increasing. The small-scale industry's growth, productivity, and performance were all dependent on GDP growth. The study discovered a bright future ahead but a low rate of job opportunities and recommends that the government and policymakers act appropriately to boost growth in the small-scale industry.

Based on the above literature a conceptual model is developed to link Entrepreneurial Marketing and MSME Sustainability.

References

Abdalhadi, Y.M., & Narci, M.T. (2021) Marketing and international entrepreneurial strategies of the sme’s and bricolage role with marketing managers.

Aldrich, H.E., & Waldinger, R. (1990). Ethnicity and entrepreneurship.Annual review of sociology, 111-135.

Azen, R., & Traxel, N. (2009). Using dominance analysis to determine predictor importance in logistic regression.Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics,34(3), 319-347.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Becherer, R.C., Helms, M.M., & McDonald, J.P. (2012). The effect of entrepreneurial marketing on outcome goals in SMEs.New England Journal of Entrepreneurship.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Calantone, R.J., Cavusgil, S.T., & Zhao, Y. (2002). Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance.Industrial marketing management,31(6), 515-524.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Collinson, E. (2002). The Marketing / Entrepreneurship Interface. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(3–4), 337–340.

Collinson, E., & Shaw, E. (2001). Entrepreneurial marketing–a historical perspective on development and practice.Management decision.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Constantinides, E. (2006). The marketing mix revisited: towards the 21st century marketing.Journal of marketing management,22(3-4), 407-438.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Crawford, S.L. (2006). Correlation and regression.Circulation,114(19), 2083-2088.

Day, G.S., & Montgomery, D.B. (1999). Charting new directions for marketing.Journal of marketing,63(4_suppl1), 3-13.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Evans, N. (2005). Assessing the balanced scorecard as a management tool for hotels.International Journal of contemporary Hospitality management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Franco, M., de Fatima Santos, M., Ramalho, I., & Nunes, C. (2014). An exploratory study of entrepreneurial marketing in SMEs: The role of the founder-entrepreneur.Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gardner, D.M. (1990). Exploring the marketing/entrepreneurship interface.BEBR faculty working paper; no. 1699.

Gliem, J.A., & Gliem, R.R. (2003). Midwest research-to-practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community education.Ohio State University, 82-88.

Hacioglu, G., Eren, S.S., Eren, M.S., & Celikkan, H. (2012). The effect of entrepreneurial marketing on firms’ innovative performance in Turkish SMEs.Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,58, 871-878.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLSSEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19 (2) pages 139-152, doi: 10.2753.MTP1069-6679190202.

Hamali, S. (2015). The effect of entrepreneurial marketing on business performance: Small garment industry in Bandung City, Indonesia.Developing Country Studies,5(1), 2225-0565.

Hamali, S., Suryana, Y., Effendi, N., & Azis, Y. (2016). Influence of entrepreneurial marketing toward innovation and its impact on business performance: A survey on small Industries of Wearing Apparel in West Java, Indonesia.International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management,4(8).

Hills, G.E., & Hultman, C.M. (2011). Academic roots: The past and present of entrepreneurial marketing.Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship,24(1), 1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hills, G.E., Hultman, C.M., & Miles, M.P. (2008). The evolution and development of entrepreneurial marketing.Journal of small business management,46(1), 99-112.

Hills, G.E., Hultman, C.M., Kraus, S., & Schulte, R. (2010). History, theory and evidence of entrepreneurial marketing–an overview.International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management,11(1), 3-18.

Hisrich, R. D. (1992). The need for marketing in entrepreneurship.Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing.

Hoy, F. (2008). Organizational learning at the marketing/entrepreneurship interface.Journal of Small Business Management,46(1), 152-158.

Hultman, C.M., & Shaw, E. (2003). The interface between transactional and relational orientation in small service firm’s marketing behaviour: A study of Scottish and Swedish small firms in the service sector.Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice,11(1), 36-51.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jabareen, Y. (2009). Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure.International journal of qualitative methods,8(4), 49-62.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kraus, S., Filser, M., Eggers, F., Hills, G.E., & Hultman, C.M. (2012). The entrepreneurial marketing domain: a citation and co?citation analysis.Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, Y.H., Huang, J.W., & Tsai, M.T. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of knowledge creation process.Industrial marketing management,38(4), 440-449.

Miles, M. (2014). Information Resource Description: Creating and Managing Metadata.

Miles, M.P., & Darroch, J. (2006). Large firms, entrepreneurial marketing processes, and the cycle of competitive advantage.European journal of marketing,40(5/6), 485-501.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Morris, M.H., Schindehutte, M., & LaForge, R.W. (2002). Entrepreneurial marketing: a construct for integrating emerging entrepreneurship and marketing perspectives.Journal of marketing theory and practice,10(4), 1-19.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Morrish, S.C., & Deacon, J.H. (2011). A tale of two spirits: entrepreneurial marketing at 42Below vodka and Penderyn whisky.Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship,24(1), 113-124.

Morrish, S.C., Miles, M.P., & Deacon, J.H. (2010). Entrepreneurial marketing: acknowledging the entrepreneur and customer-centric interrelationship.Journal of strategic marketing,18(4), 303-316.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Murphy, G.B., & Callaway, S.K. (2004). Doing well and happy about it? Explaining variance in entrepreneurs’ stated satisfaction with performance.New England Journal of Entrepreneurship.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Otieno, S., Bwisa, H.M., & Kihoro, J.M. (2012). Influence of strategic orientation on performance of Kenya's manufacturing firms operating under east African regional integration.International Journal of Business and Social Science,3(5).

Panigyrakis, G.G., & Theodoridis, P.K. (2007). Market orientation and performance: An empirical investigation in the retail industry in Greece.Journal of retailing and consumer services,14(2), 137-149.

Rashad, N.M. (2018). The impact of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions on the organizational performance within Saudi SMEs.Eurasian Journal of Business and Management,6(3), 61-71.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Soriano, D.R. (2003). Modeling the enterprising character of European firms.European Business Review.

Soriano, D.R. (2005). The new role of the corporate and functional strategies in the tourism sector: Spanish small and medium-sized hotels.The Service Industries Journal,25(4), 601-613.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stokes, D. (2000). Putting entrepreneurship into marketing: the processes of entrepreneurial marketing.Journal of research in marketing and entrepreneurship.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Webster Jr, F.E. (1992). The changing role of marketing in the corporation.Journal of marketing,56(4), 1-17.

Received: 26-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12615; Editor assigned: 05-Oct-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-12615(PQ); Reviewed: 21-Oct-2022, QC No. AMSJ-22-12615; Revised: 22-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12615(R); Published: 19-Nov-2022