Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 6

Entrepreneurial Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Mixed-Methods Exploratory Study of UAE K-12 School Leaders' Innovative Responses to COVID-19

Zeina Hojeij, Zayed University

Soulafa Al Khatib,The American University in the Emirates

Citation Information: Hojeij. Z., (2024). Entrepreneurial Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Mixed-Methods Exploratory Study of UAE K-12 School Leaders' Innovative Responses to Covid-19. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 28(6),1-19

Abstract

Educational institutions often face challenges that disrupt the education process, requiring leaders to demonstrate entrepreneurial mindsets and behaviors. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a global crisis, necessitating innovative and adaptive approaches from educational leaders. Entrepreneurial leadership, characterized by opportunity recognition, risk-taking, and innovation, is crucial to an organization's success and is linked to effective crisis management. This study investigates entrepreneurial leadership practices and competencies in crises using an exploratory mixed-method approach based on survey responses and semi-structured interviews with school leaders in the United Arab Emirates. The study proposes entrepreneurial traits and competencies that leaders must possess to ensure innovative operations and transitions in times of crisis (pre-, during, and post-crisis).

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Leadership, Education Innovation, Crisis Management, Leadership Competencies, Educational Entrepreneurship

Introduction

Educational institutions frequently encounter challenges that disrupt the learning process, necessitating leaders to exhibit entrepreneurial mindsets and behaviors. The COVID-19 pandemic presented an unprecedented global crisis, compelling educational leaders to adopt innovative and adaptive approaches. Entrepreneurial leadership, characterized by opportunity recognition, risk-taking, and innovation, is crucial to an organization's success and is intrinsically linked to effective crisis management.

Entrepreneurship in education extends beyond the traditional business context, encompassing innovative approaches to solving educational challenges and creating value within academic institutions. While entrepreneurship is often associated with profit-driven ventures, its application in education focuses on enhancing learning outcomes, improving operational efficiency, and promoting a culture of innovation within schools. Educational entrepreneurs identify opportunities, take calculated risks, and implement innovative solutions to improve teaching, learning, and school management (Satar et al., 2024; Ratten, 2020).

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on entrepreneurship in education by examining how school leaders exhibit entrepreneurial behaviors and mindsets in response to crises. While entrepreneurship is often associated with business contexts, this research highlights its crucial role in educational settings, particularly during unprecedented challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic. By exploring the intersection of entrepreneurial leadership and education, we aim to broaden our understanding of how entrepreneurial approaches can enhance the resilience and adaptability of educational institutions.

The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education was profound, affecting over 90% of the world's student population - more than 1.5 billion enrolled students worldwide (UNESCO, 2020a; UNESCO, 2020b; UNICEF, 2020). Although educational disruptions have occurred in various communities due to war, civil unrest, famine, or strikes, this marked the first time educators, students, and parents experienced such disruption internationally (Williamson et al., 2020, p. 107). This unprecedented situation created a demand for educational leaders with entrepreneurial competencies and behaviors distinct from those required in pre-pandemic times. Entrepreneurial mindsets that can develop, implement, improve, and reinforce innovative and practical ideas based on experiences before, during, and after the pandemic can significantly contribute to the success of organizational initiatives in education (Francisco & Nuqui, 2020).

While existing literature explores leadership responses in times of crisis, the challenges faced, and the competencies needed for successful navigation of such situations, there remains a gap in understanding the specific entrepreneurial leadership competencies and practices of educational leaders, particularly in the context of K-12 institutions in the UAE.

The present study seeks to address this gap by answering the following research questions:

• How did educational leaders in UAE K-12 schools demonstrate entrepreneurial behaviors and mindsets in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic?

• What innovative practices did educational leaders implement to address the crisis, and how do these practices align with entrepreneurial leadership theory?

• What entrepreneurial competencies emerged as crucial for educational leaders in effectively navigating crises and preparing for post-crisis scenarios?

By investigating these questions, this study aims to provide insights into the entrepreneurial dimensions of educational leadership during crises, offering valuable lessons for leadership development, policy formulation, and enhancing educational institutions' resilience and adaptability. Moreover, it seeks to contribute to the broader understanding of how entrepreneurial approaches can be effectively applied in non-traditional contexts, specifically in the education sector, to drive innovation and positive change.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

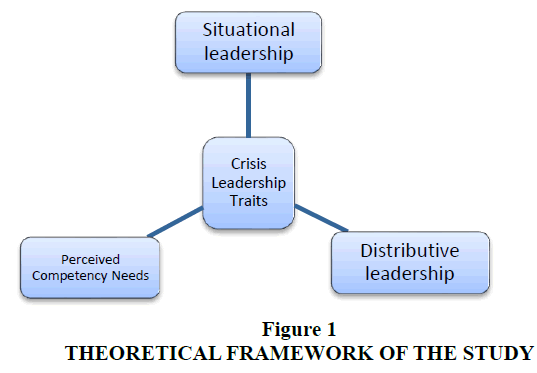

This study draws on three primary theoretical frameworks to investigate entrepreneurial leadership practices and competencies in times of crisis: situational leadership theory, distributive leadership theory, and leadership competencies in crisis management see figure 1.

Situational Leadership Theory

Situational leadership theory emphasizes the adaptability of leaders based on the specific situation they are facing. This theory, proposed by Hersey and Blanchard (1979), focuses on two key leadership behaviors: task behavior and relationship behavior. During a crisis, task-oriented leadership is often dominant as leaders need to make quick and effective decisions (Graeff, 1983; Hersey et al., 1979). Situational leadership is crucial during the pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis stages, allowing leaders to alter their approach to benefit the organization (Prabhakar & Yaseen, 2016). This adaptability is essential in managing the unpredictability and time pressures that crises bring (Islam et al., 2021). Leaders must possess flexibility, quick decision-making skills, and the ability to manage uncertainty to enhance productivity (Prabhakar & Yaseen, 2016).

Distributive Leadership Theory

Distributive leadership theory focuses on the shared and decentralized organizational leadership approach. This theory posits that leadership responsibilities are distributed among various organization members, encouraging collaboration and the development of multiple leaders (Fernandez & Shaw, 2020). This approach is particularly effective during crises, as it encourages a culture of trust and cooperation, enabling the organization to adapt swiftly to changing circumstances (Leithwood et al., 2020). For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of distributed leadership in maintaining operations, where flexibility and shared responsibilities were crucial in managing educational and organizational challenges (Geciene, 2021; Kim et al., 2024). The emphasis on professional collaboration within distributive leadership aligns with the need for collective problem-solving and decision-making during crises (NAESP, 2021; Baroudi & Hojeij, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of distributed leadership in maintaining educational operations and supporting the school community through shared responsibilities and collaborative efforts (Geciene, 2021; Kim et al., 2024).

Leadership Competencies in Crisis Management

Effective crisis leadership requires a specific set of competencies that enable leaders to manage the challenges posed by crises. These competencies include a sense of urgency, strong emotional intelligence, problem-solving skills, and effective communication (Betancourt et al., 2017). Savaneviciene et al. (2014) further categorize leadership competencies into self-management, business management, and people management components. Leaders must be decisive, adaptable, and capable of maintaining clear communication channels to navigate crises successfully (Wisittigars & Siengthai, 2019; Koehn, 2020). These competencies align with those outlined by Green Entrepreneurial Leadership, which promotes sustainable performance by fostering green product innovation and addressing ecological concerns during crises (Asad et al., 2024). Compassion, resilience, and collaboration were essential during the COVID-19 pandemic (Balasubramanian & Fernandes, 2022; Maak et al., 2021), particularly as organizations implemented green entrepreneurial strategies to balance economic and ecological outcomes (Asad et al., 2024). The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the need for leaders to demonstrate compassion, resilience, and collaboration, ensuring the well-being of their teams and the continuity of operations (Balasubramanian & Fernandes, 2022; Maak et al., 2021).

Integration of Theories

The interaction between situational leadership theory, distributive leadership theory, and leadership competencies in crisis management forms a robust conceptual framework for understanding effective educational leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. Situational leadership provides the flexibility needed to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. Distributive leadership ensures a collaborative approach, leveraging the strengths and insights of multiple leaders within the organization. Leadership competencies in crisis management offer the specific skills and attributes necessary to address the unique challenges posed by crises. Green entrepreneurial leadership further enhances this framework by incorporating sustainability into decision-making, ensuring long-term resilience (Asad et al., 2024). This integrated framework allows for a comprehensive analysis of leadership practices in UAE K-12 schools during the pandemic, highlighting the importance of adaptability, collaboration, and targeted competencies in successful crisis management.

Entrepreneurship in Education

Entrepreneurship in education extends beyond the traditional business context, encompassing innovative approaches to solving educational challenges and creating value within academic institutions (Borasi & Finnigan, 2010). Educational entrepreneurs identify opportunities, take calculated risks, and implement innovative solutions to improve teaching, learning, and school management (Pashiardis & Savvides, 2011). During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, educational entrepreneurship became pivotal as school leaders leveraged innovation to maintain operational continuity (Subroto, 2024). This entrepreneurial approach aligns with the Theory of Planned Behavior, which highlights how entrepreneurial intent and perceived behavioral control influence individuals' decision-making in times of crisis (Weber et al., 2024). In the context of K-12 education, entrepreneurial leadership involves:

• Identifying and exploiting opportunities to enhance educational outcomes

• Innovating in curriculum design, teaching methods, and school operations

• Taking calculated risks to implement new programs or technologies

• Mobilizing and creatively using resources to support educational initiatives

• Promoting a culture of innovation and continuous improvement within the school

Unlike entrepreneurship in business sectors, educational entrepreneurship often focuses on social value creation rather than profit generation. Educational entrepreneurs must navigate complex stakeholder relationships, including those of students, parents, teachers, and policymakers while adhering to educational standards and regulations (Hess, 2008). The application of entrepreneurial principles in education has gained increasing attention in recent years, particularly as educational institutions face mounting pressures to innovate and adapt to changing societal needs. Researchers have noted that entrepreneurial approaches in education can lead to improved student outcomes, enhanced operational efficiency, and greater responsiveness to community needs (Eyal & Inbar, 2003; Eyal & Kark, 2004).

Moreover, the concept of entrepreneurial leadership in education aligns closely with the idea of transformational leadership, which emphasizes inspiring and motivating followers to achieve extraordinary outcomes (Bass & Riggio, 2006). In the educational context, entrepreneurial leaders drive innovation, cultivate a shared vision, and empower their staff to become change agents themselves (Leithwood & Jantzi, 2006).

The Need for Entrepreneurial Leadership in Education During Crisis

Effective crisis leadership is critical to an institution's survival and competitiveness because of crises' unpredictability and their significant disruptive effects on work and the larger community. Dickson and Isaiah (2024) noted that global leadership requires adaptability, cultural intelligence, and dynamic capabilities, particularly in the face of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the need for academic leaders to exhibit emotional intelligence and prioritize the interests of their teams (Kezar & Holcombe, 2017). Like its corporate counterpart, entrepreneurial leadership in education involves identifying innovative solutions to complex problems, managing resources effectively, and fostering collaboration (Subroto, 2024). Crisis leadership is the process by which leaders execute action to prepare for unexpected emergencies, address their significant implications, and learn from their unpleasant experiences of crises (Bundy et al., 2017; Chitpin & Karoui, 2021).

During a crisis, emotional intelligence and stability are two highly important factors to be considered by academic leaders who ought to consider the interests of their followers above theirs. For instance, in the COVID-19 example, swift responses from certain academic institutions were granted by the already existing genuine systems of shared leadership facilitating decision-making (Kezar & Holcombe, 2017). These institutions took advantage of the shared leadership model by having flexibility, innovation, cooperation, peer-support, and/or supportive vertical or hierarchical leaders practicing distributed leadership to implement creative impact in times of change as opposed to other institutions operating in a rigid hierarchical leadership system (Kezar & Holcombe, 2017).

The intersection of entrepreneurial leadership and crisis management in education presents a unique opportunity to explore how educational leaders can leverage entrepreneurial approaches to navigate unprecedented challenges. This study aims to contribute to this emerging field by examining how K-12 school leaders in the UAE demonstrated entrepreneurial behaviors and implemented innovative practices in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Methodology

Research Design

This study adopted an exploratory research design using a mixed-methods approach to understand the experiences and practices of school leaders in the UAE during the COVID-19 pandemic (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). The mixed-methods approach was chosen to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research problem by combining quantitative and qualitative data (Creswell, 2014). This methodology allowed for an in-depth exploration of the subject and facilitated a detailed analysis of the leadership competencies and practices during the crisis.

Participants

Participants were selected using purposeful sampling, focusing on individuals who could provide the most relevant information regarding the research problem (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). The criteria for participant selection included: 1) living and working in the UAE, 2) working in the field of K-12 education, and 3) holding a leadership position in an educational institution in the UAE.

The researchers accessed a list of potential participants through their professional networks. Survey links were sent to all individuals on the list, inviting them to participate in the quantitative data collection. Additionally, volunteers from this list participated in one-on-one semi-structured interviews for the qualitative data collection.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the university's research ethics committee (approval #ZU22_023_F). Participants provided informed consent digitally for the surveys and verbally at the beginning of the recorded interviews. All responses were kept anonymous and stored securely to ensure confidentiality.

Data Collection

This exploratory mixed-methods study consisted of two phases: quantitative data collection through surveys, followed by qualitative data collection via semi-structured interviews (Creswell, 2014). For quantitative data collection, an online survey was distributed to school leaders, designed to measure entrepreneurial behaviors, innovative practices, and adaptive strategies implemented during the crisis. The survey questions were adapted from previous studies (McCarty, 2012; Tao et al., 2022) and customized to the educational context. The qualitative data collection was conducted through semi-structured interviews with a subset of survey respondents. The interview questions were guided by previous research (Hansen, 2016; Agarwal & Kaushik, 2020) and were designed to explore specific innovative initiatives implemented, decision-making processes during the crisis, and lessons learned. Interviews were conducted in either Arabic or English, depending on the participants' preferences, ensuring a comfortable environment for sharing detailed insights.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data from the surveys were analyzed using SPSS software v.25. Descriptive statistics such as means, frequencies, and standard deviations were calculated to assess leadership practices. Bivariate analysis of variance was performed to explore the relationships between variables. The reliability of the data was confirmed using Cronbach's alpha. Principal component analysis with Promax rotation was employed to extract scale items, retaining factors with an Eigenvalue greater than 1. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using SPSS AMOS v.24 to identify best practices in entrepreneurial leadership during times of crisis.

Qualitative data from the surveys and interviews were analyzed thematically, following the guidelines of Merriam and Tisdell (2015). This involved multiple readings of the transcripts to identify recurring themes and key ideas. Direct quotes were extracted to illustrate common trends and provide rich, focused information. The integration of quantitative and qualitative data allowed for a comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurial leadership practices and competencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Quantitative Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 19 principals enrolled in the study. The highest percentage was aged between 36-45 years (45.5%), females (68.2%), had a bachelor’s degree (77.3%), and had more than 10 years of experience (63.6%) (Table 1). The mean practice score was 91.74 ± 15.78, with a median of 96 (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.98).

| Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics (N=19) | |

| Variable | (%) |

| Age | |

| 36-45 years | -45.50% |

| 46-55 years | -36.40% |

| 56 years and above | -18.20% |

| Gender | |

| Male | -31.80% |

| Female | -68.20% |

| Education level | |

| Bachelor’s degree | -77.30% |

| Master | -13.60% |

| PhD | -9.10% |

| Experience level | |

| <1 year | -4.50% |

| 1-2 years | -9.10% |

| 2-5 years | -18.20% |

| 6-10 years | -4.50% |

| >10 years | -63.60% |

Entrepreneurial Leadership Practices

The leadership practices survey indicated that leaders have good knowledge and are familiar with most entrepreneurial leadership practices before, during, and after the crisis except for the element of ‘how to conduct a threat assessment’ (M=2.89; SD=1.24), which is fairly known by leaders (Table 2).

| Table 2 Leadership Practices | ||

| Leadership Practices | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| How to conduct a safety audit | 3.26 | 0.933 |

| How to conduct a threat assessment | 2.89 | 1.243 |

| How to assess the crisis | 3 | 1.054 |

| How to create a crisis plan | 3.16 | 1.015 |

| How to define roles and responsibilities of a crisis team | 3.11 | 0.994 |

| How to develop a crisis communication plan | 3.16 | 1.119 |

| How to plan action steps for placing a school in lockdown | 3.05 | 0.848 |

| How to create or help to create board policy and procedures for crisis response | 3.05 | 0.911 |

| How to size up the situation and make rapid decisions | 3.16 | 0.898 |

| How to assess the effectiveness of strategies | 3.16 | 0.898 |

| How to modify plans as needed | 3.26 | 0.933 |

| How to consider safety and security needs | 3.42 | 0.769 |

| How to communicate effectively and clearly with all stakeholders | 3.32 | 0.82 |

| How to promote students’ involvement in planning | 2.79 | 0.918 |

| How to create a nurturing environment of safety and respect | 3.21 | 0.713 |

| How to return the school environment to a calm routine as quickly as appropriate | 3.26 | 0.653 |

| How to return students to learning as quickly as possible | 3.26 | 0.806 |

| How to conduct a safety audit after the crisis | 3.26 | 0.933 |

| How to keep students and families informed | 3.32 | 0.671 |

| How to conduct daily debriefing for staff in recovery time | 3.26 | 0.653 |

| How to assess the emotional needs of staff, students, and families | 3.21 | 0.713 |

| How to evaluate and consider future implications of crisis and response | 3.16 | 0.765 |

Factor analysis presented in Table 3 confirmed the results of the descriptive statistics discussed. Item 6 (How to develop a crisis communication plan) was removed from the analysis since it did not load. The elements formed 4 conceptually sound components (factors) explaining 87.11 % of total variance (KMO=.782, p<.001). The first component had 10 elements, and it explained 66.83 % of total variance with Eigenvalue of 8.548; the elements were mainly related to the principals’ knowledge of the practices during the crisis, with four elements of the practices before the crisis and one element after crisis. The second component had 5 elements: two of them were conducted during the crisis while three were practiced in the first stages after the crisis, and it explained 9.26% of total variance with Eigenvalue of 4.425. The third component was composed of three elements practiced before crisis, while the last component had three elements practiced after the crisis.

| Table 3 Factor Analysis of the Practice Scale Items | |||||

| Question | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | H2 communalities |

| 1.How to conduct a safety audit | 0.626 | 0.891 | |||

| 2.How to conduct a threat assessment | 1.096 | 0.918 | |||

| 3.How to assess the crisis | 0.924 | 0.935 | |||

| 4.How to create a crisis plan | 0.505 | 0.822 | |||

| 5.How to define roles and responsibilities of a crisis team | 0.712 | 0.886 | |||

| 7.How to plan action steps for placing a school in lockdown | 0.861 | 0.928 | |||

| 8.How to create or help to create board policy and procedures for crisis response | 0.489 | 0.87 | |||

| 9.How to size up the situation and make rapid decisions | 0.916 | 0.909 | |||

| 10.How to assess the effectiveness of strategies | 0.79 | 0.875 | |||

| 11.How to modify plans as needed | 0.774 | 0.949 | |||

| 12.How to consider safety and security needs | 0.958 | 0.763 | |||

| 13.How to communicate effectively and clearly with all stakeholders | 0.572 | 0.874 | |||

| 14.How to promote students’ involvement in planning | 0.79 | 0.852 | |||

| 15.How to create a nurturing environment of safety and respect | 0.835 | 0.865 | |||

| 16.How to return the school environment to a calm routine as quickly as appropriate | 0.844 | 0.892 | |||

| 17.How to return students to learning as quickly as possible | 1.042 | 0.904 | |||

| 18.How to conduct safety audit after the crisis | 0.788 | 0.912 | |||

| 19.How to keep students and families informed | 0.588 | 0.914 | |||

| 20.How to conduct daily debriefing for staff in recovery time | 0.835 | 0.676 | |||

| 21.How to assess emotional needs of staff, students, and families | 0.917 | 0.799 | |||

| 22.How to evaluate and consider future implications of crisis and response | 0.929 | 0.863 | |||

| Percentage of variance explained | 66.83 | 9.26 | 5.62 | 5.4 | |

Correlation between sociodemographic characteristics and practice variables

None of the sociodemographic characteristics was significantly associated with the practice variables except for elements 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 11, which were significantly positively correlated to the principals’ experience, as shown in Table 4, especially element 3 (how to assess the crisis) which indicated a significantly high correlation p<0.01.

| Table 4Correlation between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Practice Variables | ||||||||

| Question | Gender | Education Level | Age | Experience Level | ||||

| r | Sig. | r | Sig. | r | Sig. | r | Sig. | |

| 1.How to conduct a safety audit | -0.177 | 0.468 | 0.178 | 0.465 | 0.269 | 0.265 | .465* | 0.045 |

| 3.How to assess the crisis | -0.221 | 0.364 | 0 | 1 | 0.287 | 0.233 | .637** | 0.003 |

| 4.How to create a crisis plan | -0.121 | 0.623 | -0.077 | 0.754 | 0.208 | 0.392 | .539* | 0.017 |

| 6.How to develop a crisis communication plan | -0.109 | 0.656 | -0.07 | 0.777 | 0.053 | 0.828 | .489* | 0.034 |

| 8.How to create or help to create board policy and procedures for crisis response | -0.215 | 0.377 | -0.029 | 0.908 | 0.271 | 0.261 | .479* | 0.038 |

| 9.How to size up the situation and make rapid decisions | -0.007 | 0.978 | -0.087 | 0.724 | 0.235 | 0.332 | .459* | 0.048 |

| 11.How to modify plans as needed | -0.052 | 0.831 | -0.033 | 0.892 | 0.188 | 0.441 | .465* | 0.045 |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level

Qualitative Results

The qualitative data analysis yielded 6 themes related to entrepreneurial leadership during the crisis.

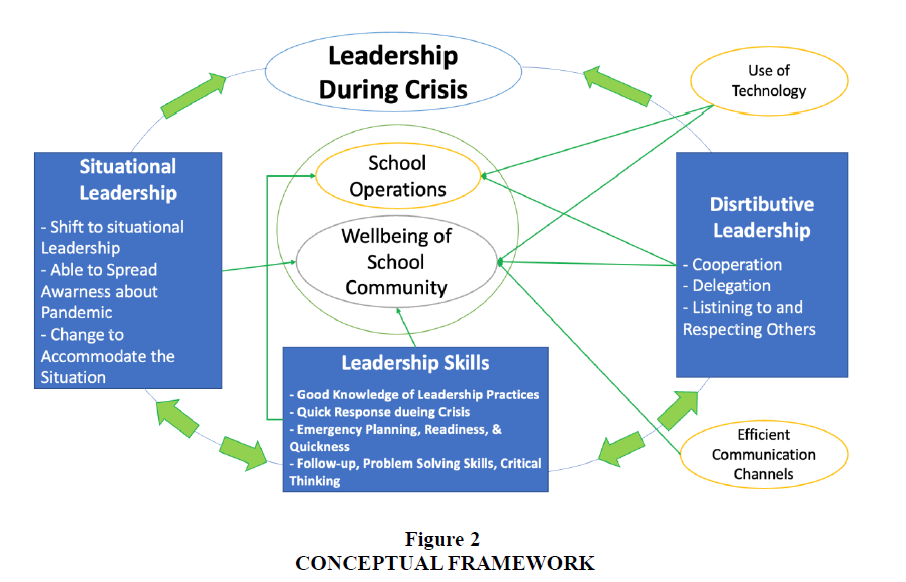

Theme 1: The importance of quick response to problems and changes

Most of the respondents (81%) believe that quick response to change is a prime leadership skill in time of crisis. Hence, dealing with problems critically and planning decision making (being decisive) come hand in hand with crises as an important skill of good leaders. Accordingly, emergency planning, readiness and quickness are found to be among the top entrepreneurial leadership strategies that had a positive impact on the school operations and the wellbeing of the school community in time of crisis. Sample responses are found below.

‘The ability to take actions and not being reckless are two important entrepreneurial leadership skills.’ (Female, with 2 to 5 years of experience)

‘The quick response to occurring changes, the ability to set priorities, and having good communication with the team are important leadership skills during a crisis.’ (Female, with more than 10 years of experience)

Theme 2: Flexibility and adaptability

Almost half the participants (48%) reported that flexibility and adaptability are other top priorities in entrepreneurial leadership skills. They also stated that they were the main changing factors in the leadership approach at their institutions. Flexibility was also described as one of the strategies that positively impacted the well-being of the school community. Sample responses are found below.

‘Having timely response and flexibility are two important leadership skills during a crisis.’ (Female, with more than 10 years of experience)

‘Being proficient in adaptability with crises and having strategic thinking and risk analysis skills are among the priority skills that leaders should have to be able to deal with a crisis situation.’ (Male, with more than 10 years of experience)

Theme 3: Communication channels

As an entrepreneurial leadership skill, good communication comes third, according to 43% of the participants. It was mentioned as a crucial strategy in school operations since it impacts colleagues and staff in a positive manner. This includes the transparency and objectivity of the leader, as well as meetings and lectures that were held to support students, parents, and teachers. It was also mentioned as a crucial strategy in school operations since it impacts colleagues and staff in a positive manner. According to the participants, efficient communication channels allowed a proper link among all parties at school, which was a major change in the leadership approach at their institutions. Sample responses are found below.

‘Based on our latest experience during crises, I noticed the importance of having good and effective communication channels to link the school community.’ (Female, with less than 1 year of experience)

‘Delegating tasks, remote communication, and using technology in a good and wide manner to facilitate communication are important during crises situations.’ (Male, with more than 10 years of experience)

Theme 4: Technology integration

Technology in time of crisis proved to be the number one entrepreneurial leadership strategy that positively impacted the school operations; 28.5% of the participants mentioned its benefits on different levels. It affected all parties: teachers, students, parents, and administration staff. Technology was needed on all levels: to teach, to learn, to train, to communicate messages, to meet, etc.…. Thus, new teaching activities, materials, and apps had to be used to deal with the crisis. E-leadership became necessary, and everybody, including parents, had to use technology to be part of the teaching/learning experience. Consequently, technology use positively impacted the well-being of the school community and was a major change in the school operations. Sample responses are found below.

‘The use of remote teaching was very important and did not affect the educational level of students.’ (Male, more than 10 years of experience)

‘The use of technology made it easy for school leaders to be knowledgeable of details and enabled them to be able to plan better and make sure that all work processes are going well with high precautions.’ (Female, with more than 10 years of experience)

Theme 5: Safety measures and prevention

In their accounts, 38% of the participants highlighted the importance of a leader being able to spread awareness of the pandemic and provide the help needed to prevent its spread. At the same time, many pinpointed the change that happened in their institution to accommodate the new situation. It was mentioned as one of the leadership strategies that impacted positively both the wellbeing of the school community and the school operations: providing healthcare tips and help to teachers, parents, and students, in addition to taking safety measures at the school premises and prevention steps to minimize the risks of contamination. Here, the following leadership skills are needed: follow-up, problem-solving, critical thinking, and proper conduct. Sample responses are found below.

‘Providing all needed support to teachers to be able to work from home and be safe.’ (Female, with 2 to 5 years of experience)

‘Starting in working in shifts, taking good safety measures, and having early detection of cases helped a lot in protecting school staff and students.’ (Female, with more than 10 years of experience)

Theme 6: Situational leadership

This study also showed that the main change that the leadership at the participants’ institution had gone through is the leadership style: it became more of a situational leadership. On the level of cooperation, it was clear that more was needed in the time of crisis. Listening to and respecting others’ opinions was clearly a turning point in such times. Leaders were not facing issues single-handedly: they delegated some chores to others as they saw fit. Sample responses are found below.

‘Being positive and keeping positive communication with all involved was very important during times of crisis.’ (Female, with 6 to 10 years of experience)

‘Shifting to delegation leadership is effective during times of hardships.’ (Female, with more than 10 years of experience)

‘Involve students and their parents in psycho-social support sessions and in the school activities and programs to ensure their wellbeing.’ (Female, with 2 to 5 years of experience)

In general, it was clear that participants were aware of the crisis effect on their institutions, and they were trying hard to find solutions to the problems they were facing. It was clear from the survey that they were taking humane cases into consideration such as providing computers for the ones that needed them (P2) and thanking individuals in their staff whenever they did the proper job (P8). Another interesting finding is the frequent mentioning of the skills that were perceived as important in crisis time such as persuasion (20%), the ability to prioritize (9.5%), positive attitude (9.5%), strategic thinking (23.8%), calmness (19%), and evaluation and control (33.33%). Sample responses are found below.

‘They provided computers and all needed material for teachers and students to be able to study at home.’ (Female with more than 10 years of experience)

‘Taking into consideration individual situation and being supportive.’ (Female, with more than 10 years of experience)

‘Thinking strategically and setting strategies and shifting into remote studying is very important.’ (Male with more than 10 years of experience)

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into how K-12 school leaders in the UAE demonstrated entrepreneurial leadership during the COVID-19 crisis. The findings reveal a significant shift towards entrepreneurial behaviors and innovative practices in educational leadership, supporting the growing body of literature on entrepreneurship in education (Pashiardis & Savvides, 2011; Borasi & Finnigan, 2010). The role of flexible leadership, including adaptability in rapidly evolving situations, is further emphasized by green entrepreneurial leadership frameworks. Leaders are expected to balance immediate response needs with long-term sustainability (Asad et al., 2024). In times of crisis, dynamic leadership capabilities are essential to manage organizational operations and social and environmental considerations see figure 2.

In response to the first research question regarding entrepreneurial behaviors and mindsets, the study reveals a significant shift towards entrepreneurial practices among UAE school leaders. The high scores on innovativeness and proactiveness suggest that these leaders embraced entrepreneurial approaches in response to the crisis, aligning with the concept of entrepreneurial leadership in education as a dynamic process involving vision, change, and creation (Bagheri & Pihie, 2011). This finding extends our understanding of how entrepreneurial qualities manifest in crises, where rapid adaptation is crucial. Interestingly, the study found a positive correlation between years of experience and entrepreneurial behavior, contradicting previous research suggesting that more experienced leaders might resist change (e.g., Ng & Feldman, 2013). Instead, the results support the notion that experienced educational leaders can leverage their knowledge to identify and exploit new opportunities, even in unfamiliar crises.

Addressing the second research question on innovative practices, the study identified key areas of innovation, including digital transformation of teaching, remote leadership and management, community engagement and support, and resource mobilization and reallocation. These findings demonstrate how entrepreneurial leadership translates into practical actions during a crisis, supporting Ratten's (2020) argument that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need for innovation in educational delivery and management. This innovation in education during crises is consistent with the digital transformations and resourceful behaviors seen in other sectors, such as SMEs, where leaders utilized digital platforms and limited resources to maintain operations during the pandemic (Subroto, 2024). This mirrors the bricolage concept in entrepreneurship where leaders creatively adapt available tools to sustain operations (Baker & Nelson, 2005). This ability to reconfigure resources aligns with the dynamic capabilities framework (Teece et al., 1998), highlighting how entrepreneurial leaders in education can sense and seize opportunities even with limited resources.

The qualitative findings on risk-taking in pedagogical approaches and agile decision-making processes reflect key entrepreneurial leadership aspects, addressing the first and second research questions. The implementation of novel teaching methods and rapid curriculum redesign demonstrates how educational leaders applied entrepreneurial risk-taking to address the challenges posed by the pandemic. This agility in decision-making aligns with the principles of effectuation theory (Sarasvathy, 2001), where leaders focus on controlling available means to create new ends in uncertain environments. Similarly, the green entrepreneurial leadership framework emphasizes sustainability-focused decision-making and resource management. Leaders in educational settings, like those in entrepreneurial firms, must balance limited resources with the need for innovation to ensure sustainable outcomes (Asad et al., 2024).

Concerning the third question research regarding crucial entrepreneurial competencies, the study highlights several unique aspects of entrepreneurial leadership in education. These include navigating stakeholder complexity, innovating within regulatory constraints, maintaining a social impact focus, overcoming resource limitations, and adopting a long-term perspective on outcomes. UAE school leaders demonstrated the ability to balance diverse stakeholder needs, find creative solutions within regulatory frameworks, prioritize student well-being and learning continuity, and creatively repurpose resources. These findings align with recent research on the contextual nature of educational entrepreneurship (Yemini & Sagie, 2015) and the importance of social value creation in educational settings (Pashiardis & Savvides, 2011). This also resonates with global leadership studies, where managing stakeholder complexity, regulatory environments, and social impacts are central to effective leadership in crisis settings (Dickson & Isaiah, 2024). The ability to navigate such challenges is essential for both educational and corporate leaders working in volatile environments.

The emphasis on encouraging innovative thinking among staff emphasizes the role of entrepreneurial leaders in cultivating a culture of innovation within their organizations. This finding supports the concept of entrepreneurial leadership as a distributed phenomenon (Leithwood & Sun, 2012), where leaders empower others to engage in entrepreneurial behaviors. It also aligns with recent studies on the importance of collective entrepreneurship in educational settings (Kolleck, 2019). Moreover, this finding is aligned with research in entrepreneurial education, where collective innovation is promoted through entrepreneurial courses and collaboration (Weber et al., 2024). By distributing leadership responsibilities, educational leaders were able to foster a culture of shared innovation during the crisis.

The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of entrepreneurial leadership in education, particularly in crisis situations. They suggest that successful educational leaders must not only possess traditional entrepreneurial skills but also be able to adapt these skills to the unique challenges and opportunities present in educational settings. This has significant implications for leadership development programs and policy initiatives encouraging innovation and resilience in educational institutions.

Furthermore, the results highlight the need for a contextualized approach to entrepreneurial leadership in education. The unique aspects identified, such as stakeholder complexity and the social impact focus, underscore the importance of developing specialized frameworks for understanding and developing entrepreneurial leadership in educational contexts (Pashiardis & Savvides, 2011; Yemini & Sagie, 2015). Future research could explore how these contextual factors influence the development and expression of entrepreneurial leadership in different educational settings and cultures.

In conclusion, this study provides empirical evidence of the critical role of entrepreneurial leadership in education during times of crisis. It demonstrates how UAE school leaders exhibited high entrepreneurial orientation, engaging in opportunity recognition, innovative resource utilization, and risk-taking in pedagogical approaches. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature on entrepreneurship in education and offer practical insights for educational leadership development and policy formulation in an increasingly complex and rapidly changing educational landscape.

Limitations

This study provides valuable insights into entrepreneurial leadership in education during the crisis, but it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. The focus on the UAE context may restrict the generalizability of findings to other cultural and educational settings, given the significant variations in educational systems, regulations, and cultural norms across countries. The study's temporal constraints, capturing leadership behaviors during the acute phase of the COVID-19 crisis, may overlook long-term entrepreneurial strategies or their evolution over time. While the sample size was sufficient for qualitative insights, it may only partially represent some educational leaders in the UAE. It could overrepresent certain types of schools or leaders who are more inclined to participate in research. The reliance on self-reported data from leaders introduces the potential for social desirability bias, possibly leading to overestimating entrepreneurial behaviors.

Additionally, the study's focus on the COVID-19 pandemic may limit its applicability to other types of crises that educational institutions might face. The primary focus on leaders' perspectives might need to include important insights from different stakeholders like teachers, students, or parents. Lastly, the tools used to measure entrepreneurial leadership may only partially capture some relevant aspects of this construct in an educational setting, given the unique nature of education compared to business contexts.

Recommendations

Based on the study's findings and considering its limitations, we propose several recommendations for practice, policy, and future research. In practice, leadership development programs should integrate entrepreneurial mindsets, incorporating modules on entrepreneurial thinking, opportunity recognition, and innovative problem-solving. These programs should implement experiential learning through simulations or real-world projects, allowing aspiring educational leaders to practice entrepreneurial skills in context. Encouraging cross-sector collaborations between educational institutions and business schools or entrepreneurship centers can bring fresh perspectives to educational leadership. Developing comprehensive risk management frameworks tailored to educational settings and enhancing technology integration through ongoing professional development are also crucial.

On the policy front, we recommend developing regulations that allow for greater flexibility and autonomy in school leadership while maintaining educational standards. Policymakers should consider establishing recognition programs or funding opportunities to incentivize innovation in schools. Updating accreditation standards to incorporate measures of innovation and adaptability could encourage entrepreneurial practices. Additionally, creating policies that facilitate public-private educational partnerships could provide schools with more avenues for resource acquisition and innovation funding.

For future research, we suggest conducting longitudinal studies to examine the sustained impacts of entrepreneurial leadership on educational outcomes, school culture, and system resilience. Cross-cultural comparisons could help identify universal principles and culture-specific practices of entrepreneurial leadership in education. Expanding research to include multi-stakeholder perspectives would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of entrepreneurial leadership. Investigating how entrepreneurial leadership manifests across various types of crises beyond pandemics could offer valuable insights. Developing and validating measurement tools designed explicitly for assessing entrepreneurial leadership in educational contexts is also necessary. Future studies should explore the direct and indirect effects of entrepreneurial leadership practices on student outcomes and identify barriers to implementing entrepreneurial approaches in education. By addressing these recommendations, we can reach a more comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurial leadership in education and develop more effective strategies for its implementation and development.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of entrepreneurial leadership in education, particularly during times of crisis. The findings demonstrate that UAE school leaders exhibited high entrepreneurial orientation, engaging in opportunity recognition, innovative resource utilization, and risk-taking in pedagogical approaches. The unique aspects of entrepreneurial leadership in education, including stakeholder complexity, regulatory constraints, and social impact focus, highlight the need for specialized approaches to developing and supporting entrepreneurial leaders in educational contexts.

The research reveals that successful educational leaders must not only possess traditional entrepreneurial skills but also be able to adapt these skills to the specific challenges and opportunities present in academic settings. By incorporating entrepreneurial skills and mindsets into leadership development programs, we can develop a new generation of educational leaders equipped to navigate future challenges and drive meaningful innovation in education.

While this study focused on the UAE context during the COVID-19 pandemic, its insights have broader relevance to understanding how entrepreneurial leadership can enhance educational institutions' resilience and adaptability globally. The entrepreneurial approaches identified in this study can be adapted and applied in different educational contexts, contributing to the overall improvement and innovation in education systems worldwide.

As we move forward, promoting entrepreneurial leadership in education will be crucial in creating more resilient, innovative, and adaptive educational systems capable of meeting the challenges of an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world. This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on entrepreneurial leadership in education and provides a foundation for future research and practice in this critical area. By continuing to explore and develop entrepreneurial leadership in education, we can better prepare our educational systems to thrive in the face of future challenges and opportunities.

References

Agarwal, S., & Kaushik, J.S. (2020). Student's perception of online learning during the COVID pandemic. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 87, 554.

Asad, M., Sulaiman, M. A. B. A., Ba Awain, A. M. S., Alsoud, M., Allam, Z., & Asif, M. U. (2024). Green entrepreneurial leadership and performance of entrepreneurial firms: Does green product innovation mediate?. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2355685.

Bagheri, A., & Pihie, Z. A. L. (2011). Entrepreneurial leadership: Towards a model for learning and development. Human Resource Development International, 14(4), 447-463.

Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329-366.

Balasubramanian, S., & Fernandes, C. (2022). Confirmation of a crisis leadership model and its effectiveness: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 1-31.

Baroudi, S., & Hojeij, Z. (2020). The role of self-efficacy as an attribute of principals' leadership effectiveness in K-12 private and public institutions in Lebanon. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(4), 457-471.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Betancourt, J. R., Tan-McGrory, A., Kenst, K. S., Phan, T. H., & Lopez, L. (2017). Organizational change management for health equity: Perspectives from the disparities leadership program. Health Affairs, 36(6), 1095-1101.

Borasi, R., & Finnigan, K. (2010). Entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviors that can help prepare successful change-agents in education. The New Educator, 6(1), 1-29.

Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M. D., Short, C. E., & Coombs, W. T. (2017). Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation, and research development. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1661-1692.

Chitpin, S., & Karoui, O. (2021). COVID-19 and educational leadership: Resolving educational issues. Academic Letters.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Dickson, R. K., & Isaiah, O. S. (2024). An exploratory analysis of effective global leadership on organizational performance in the 21st century. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 28(3), 1-18.

Eyal, O., & Inbar, D. E. (2003). Developing a public school entrepreneurship inventory: Theoretical conceptualization and empirical examination. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 9(6), 221-244.

Eyal, O., & Kark, R. (2004). How do transformational leaders transform organizations? A study of the relationship between leadership and entrepreneurship. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 3(3), 211-235.

Fernandez, A. A., & Shaw, G. P. (2020). Academic leadership in a time of crisis: The coronavirus and COVID-19. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(1).

Francisco, C., & Nuqui, A. V. (2020). Emergence of a situational leadership during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Academic Multidisciplinary Research (IJAMR), 4(10), 15-19.

Ge?ien?, J. (2021). Organizational resilience management in the face of a crisis: Results of a survey of social service institutions before and during a Covid-19 pandemic. Contemporary Research on Organization Management and Administration (CROMA journal), 9(1).

Graeff, C. L. (1983). The situational leadership theory: A critical view. The Academy of Management Review, 8(2), 285-291.

Hansen, K. M. (2016). Effective school leadership practices in schools with positive climates in the age of high-stakes teacher evaluations. All NMU Master's Theses, 125.

Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., & Natemeyer, W. E. (1979). Situational leadership, perception, and the impact of power. Group & Organization Studies, 4(4), 418-428.

Hess, F. M. (2008). The future of educational entrepreneurship: Possibilities for school reform. Harvard Education Press.

Islam, A., Zawawi, N. F. M., & Abd Wahab, S. (2021). Rethinking survival, renewal, and growth strategies of SMEs in Bangladesh: The role of spiritual leadership in crisis situation. PSU Research Review.

Jarvis, A., & Mishra, P. K. (2020). Leadership for learning: Lessons from the great lockdown. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 27(2), 316-331.

Kezar, A. J., & Holcombe, E. M. (2017). Shared leadership in higher education. Washington, DC: American Council on Education, 1-36.

Kim, J., Lee, H. W., & Chung, G. H. (2024). Organizational resilience: leadership, operational and individual responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(1), 92-115.

Koehn, N. (2020). Real leaders are forged in crisis. Harvard Business Review.

Kolleck, N. (2019). Motivational aspects of teacher collaboration. Frontiers in Education, 4, 122.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201-227.

Leithwood, K., & Sun, J. (2012). The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 387-423.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership and Management, 40(1), 5-22.

Maak, T., Pless, N., & Wohlgezogen, F. (2021). The fault lines of leadership: Lessons from the global COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Change Management, 21(1), 1-21.

McCarty, S. P. (2012). K–12 school leaders and school crisis: An exploration of principals' school crisis competencies and preparedness (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh).

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons.

NAESP (2021). Lead through crisis together: Distributed leadership can help schools excel beyond the pandemic. 11(13).

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2013). A meta?analysis of the relationships of age and tenure with innovation?related behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 585-616.

Pashiardis, P., & Savvides, V. (2011). The interplay between instructional and entrepreneurial leadership styles in Cyprus rural primary schools. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(4), 412-427.

Prabhakar, G. V., & Yaseen, A. (2016). Decision-making styles and leadership: Evidence from the UAE. International Journal of Management Development, 1(4), 287-306.

Ratten, V. (2020). Coronavirus (Covid-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(5), 503-516.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243-263.

Satar, M., Alharthi, S., Asad, M., Alenazy, A., & Asif, M.U. (2024). The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Networking between Entrepreneurial Alertness and the Success of Entrepreneurial Firms. Sustainability, 16, 4535.

Savaneviciene, A., Ciutiene, R., & Rutelione, A. (2014). Examining leadership competencies during economic turmoil. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 156, 41-46.

Subroto, W. T. (2024). SMEs development during the COVID-19 pandemic: SWOT analysis of Surabaya Metropolitan City. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 28(5), 1-14.

Tao, W., Lee, Y., Sun, R., Li, J., & He, M. (2022). Enhancing employee engagement via leaders' motivational language in times of crisis: Perspectives from the COVID-19 outbreak. Public Relations Review, 48(1).

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1998). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533.

UNESCO. (2020a). School closures caused by Coronavirus (Covid-19).

UNESCO. (2020b). COVID-19 disruption and response.

UNICEF. (2020). UNICEF and Microsoft launch global learning platform to help address COVID-19 education crisis.

Weber, A., Ho, M., & Nguyen, J. (2024). Entrepreneurship education: An application of the theory of planned behavior and entrepreneurial intentions of allied health students. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 28(S5), 1-12.

Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 107-114.

Wisittigars, B., & Siengthai, S. (2019). Crisis leadership competencies: The facility management sector in Thailand. Facilities, 37(13/14), 881-896.

Yemini, M., & Sagie, N. (2015). School–nongovernmental organization engagement as an entrepreneurial venture. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(4), 543-571.

Received: 05-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. IJE-24-15322; Editor assigned: 06-Sep-2024, Pre QC No. IJE-24-15322 (PQ); Reviewed: 20-Sep-2024, QC No. IJE-24-15322; Revised: 26-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. IJE-24-15322 (R); Published: 30-Sep-2024