Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 4

Entrepreneurial Intentions and Motivation of Young Native Females in the UAE

Dr. Roberta Fenech, Higher Colleges of Technology

Dr. Priya Baguant, Higher Colleges of Technology

Dr. Dan Ivanov, Higher Colleges of Technology

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationships between perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, entrepreneurial intentions, motivations and cognitive planning of young female Emirati undergraduates by putting forward two theoretical models that integrate the theory of planned behaviour and the expectancy theory of motivation. The two theoretical models are researched using a quantitative method utilizing a questionnaire. The participants are 337 undergraduate female Emirati students from Dubai and the northern emirates. The difference between the two theoretical models is that whilst in the first model perceived behavioural control and subjective norms drive the entrepreneurial intentions and motivation is what links the intentions to the cognitive planning and actual actions, in the alternative model cognitive planning is researched as the result of perceived behavioural control and subjective norms, and is considered to precede entrepreneurial intentions. The main finding is that the fit between the theory of planned behaviour and the expectancy theory of motivation is best supported in the model where perceived behavioural control and subjective norms are significantly linked to cognitive planning which in turn is significantly linked to entrepreneurial intentions mediated by valence and outcome expectations.

Keywords

Theory of Planned Behaviour, Expectancy Theory, Entrepreneurial Intentions, Cognitive Planning, Emirati Females, Quantitative.

Introduction

New entrepreneurs are those who dare to create a new business after identifying an opportunity by taking the risk and accepting the uncertainty in order to achieve profit and growth (Zimmerer and Scarborough, 2005). In literature, amongst the words used to describe the entrepreneur are innovator, creator, locator and implementer (Carsrud and Brannback, 2011)

This investigative study addresses the perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, entrepreneurial intentions, motivations and cognitive planning of young Emirati female undergraduate entrepreneurs reading for a degree in business studies. Studying young entrepreneurs is interesting because such individuals are in the period of their life during which a range of decisions regarding opportunities are being made and solidified (Turner and Nguyen, 2005; Langevang, 2008).

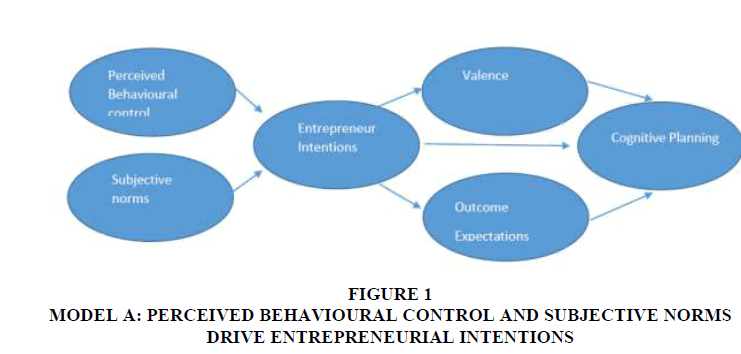

Two models are presented for investigation in this research and the purpose of this study is to identify which model is supported by findings. Model A portrays the link between perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, intention, motivation and the cognitive process, resulting from the former four constructs of perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, motivation and intention. Perceived behavioural control and subjective norms are studied as the precursors for entrepreneurial intentions and the mediating link between such intentions and the cognitive planning processes preceding the actual activity is motivation.

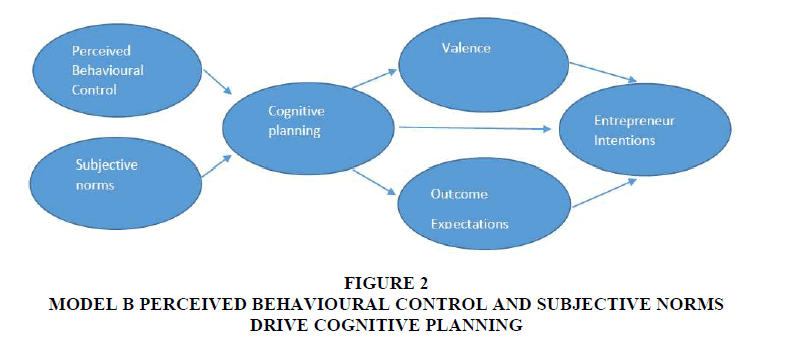

Model B also shows the link between perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, intention, motivation and the cognitive process however cognitive processes precede entrepreneurial intentions and the mediating link between cognitive planning and intentions remains motivation. Perceived behavioural control and subjective norms are now the precursors to cognitive planning in this alternative model. Motivation in both models encompasses expectancy that effort results in the desired outcome, instrumentality of the entrepreneurship activity to achieve desired results and valence which refers to desirability of the results of entrepreneurship activity.

Model A: Perceived behavioural control and subjective norms lead to entrepreneurial intentions that form a process of cognitive planning mediated by motivation.

Model B: Perceived behavioural control and subjective norms lead to cognitive planning that forms entrepreneurial intentions mediated by motivation.

Research in entrepreneurship has confirmed the positive relationship between intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities and actual entrepreneurial engagement (Kolvereid and Isaksen, 2006; Chuluunbaatar et al., 2011; Guzmán-Alfonso and Guzmán-Cuevas, 2012; Kautonen et al., 2013). However there still is criticism regarding the intention-behaviour relationship that is based on the argument that intentions do not always lead to action and that third variables moderate the intention-behaviour relationship (Conner et al., 2002). This third variable for the purpose of this study is motivation.

This research contributes to the already existing body of literature on entrepreneurial intentions by using as a framework the theoretical relationship between the theory of planned behavior and the expectancy theory of motivation as well as by putting forward two alternative models for investigation. This study’s theoretical relationship has not received enough attention in literature therefore presents meaningful avenues for future research. This theoretical relationship underlies the link between perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, intentions, motivation and cognitive planning.

Linan and Fayolle (2015) in a systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions state that the integration of theories is what is increasing the theoretical strength and methodological rigor of contributions on entrepreneurial intentions. This theoretical framework is adopted in the construction of a questionnaire that is used amongst undergraduate female Emirati studying business and in the analysis and interpretation of results.

Theoretical Framework

Theory of Planned Behaviour

The theory of planned behavior has been used to explain and predict a large number of entrepreneurial intentions and behaviours (Lortie and Castogiovanni, 2015). This theory has mainly been adopted by researchers (Kolvereid, 1996b; Tkashev and Kolvereid, 1999; Krueger et al., 2000; Kolvereid and Isaksen, 2006), using student samples however in different cultural contexts to the current context of the Middle East.

In this theory behavioural intentions are determined by: the degree to which the individual has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation of the behaviour in question (valence and outcome expectations in this study); subjective norms, which refer to the perceived social pressure to perform (or not perform) the behaviour; and perceived behavioural control, meaning a belief that one has a large amount of control over a behavior (Ajzen 1985; Ajzen and Madden, 1986). Intentions are understood to be indicators of how much effort a new entrepreneur is willing to invest. The stronger the intention the more likely entrepreneurial activity exists. Motivation mediates this link between intention and entrepreneurial activity (Armitage and Conner, 2001).

Kiriakidis (2015) noted that variability observed in research in the performance of perceived behavioural control as a determinant of intentions and action, suggests that certain factors serve as moderators of the relationships postulated by the theory. This study introduces the mediating variable of motivation.

Expectancy Theory

Theories of motivation have an increasingly important role to play in entrepreneurship research (Renko et al., 2012). Motivation is required as encouragement, morale, and interest to achieve success in business development. Robbins and Judge (2013) write that motivation is the process of explaining the intensity, direction, and persistence of an individual to achieve the goal. Therefore, entrepreneurs need to pay attention to the motivational aspect that supports the success of their business.

There are various theories of motivation that may be applied to entrepreneurship, in particular the aspiration of being an entrepreneur. One such theory that has received a lot of attention amongst researchers in the field of entrepreneurship is the Expectancy Theory of Motivation. Vroom’s Expectancy theory of motivation states that actions of an individual are driven by expected consequences. Expectancy is the subjective probability that effort leads to an outcome or performance. Instrumentality is also an important part of this theory and refers to the belief that, if one meets performance expectations, he or she will receive a greater reward. For an individual to be motivated there also needs to be valence which is the value that an individual bases on this reward (Vroom, 1964).

Douglas and Shepherd (2000) found that the actions of the nascent entrepreneur are driven by the expected consequences of income. The amount of work effort anticipated to achieve this income, the risk involved and other factors such as the person’s attitude for independence and perceptions of the anticipated work environment all influence the effort exerted by the entrepreneur. Also in the context of nascent entrepreneurs, Renko et al. (2012) find that out of the outcome measures for intention, intended effort, task performance, and time spent on task, expectancy constructs have the strongest relationship with intended effort. Furthermore Renko et al. (2012) found that when a nascent entrepreneur’s motivation is mainly driven by financial success (valence), the intended effort level remains high regardless of expectancy level (that is, regardless of whether one believes that his hard work can actually lead to a successful startup). New entrepreneurs might doubt their skills and abilities (low expectancy levels), but still intend to put a lot of effort into starting a business since there may be lack of other opportunity. The authors conclude that expectancy theory provides potential explanations for entrepreneurial motivation.

Similarly Edelman et al. (2010) also write that nascent entrepreneurs are motivated to expend effort towards setting up a business because they believe this leads to desired outcomes. Amongst the desired outcomes are the financial outcomes, the need of self-realization, the need for recognition, the need to be a role model and the need for independence. Financial outcomes are not the sole motivators and this was confirmed by Wiklund et al. (2003) who found that people start their business ventures for a number of reasons other than growth and maximizing financial return. Orser and Hogarth-Scott (2002) also found similar results and less than half of their sample were interested in financial growth.

In a study carried out by Soomro and Shah (2014), data showed that need for achievement, innovation and self-esteem variables have positive and significant impact on developing attitudes towards entrepreneurship. Achievement, innovation and self-esteem lead to a greater subjective probability or expectancy that effort leads to an outcome as is stated in the expectancy theory of motivation.

With further reference to expectancy, Douglas (2012) distinguishes between two types of entrepreneurs, namely the entrepreneur whose expectancy is growth and the entrepreneur whose expectancy is independence. Entrepreneurs with expectations of independence seem to be characterized by relatively low risk tolerance, and a potentially significant positive attitude to autonomy, while entrepreneurs with expectancies of growth seem to be characterized by high Entrepreneurial self-efficacy; negative attitude to work enjoyment, and masculine traits.

This research is developed within the field of social psychology as entrepreneurship is analyzed by shedding light on the mental processes that stem from entrepreneurial intentions. Literature on entrepreneurial intentions is vast and as Linan and Fayolle (2015) state what is needed is not to start anew with every study but to address existing gaps. This research study makes an attempt at this by integrating the theory of planned behaviour and the expectancy theory. The inclusion of the expectancy theory in research on entrepreneurial intentions is recommended by Linan and Fayolle (2015) in their systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions, they state that “motivational antecedents also deserve further attention to better understand the cognitive process leading to the startup decision”. Another recommendation made in previous literature is methodological by nature and addresses the need to conduct research amongst would-be entrepreneurs or nascent entrepreneurs (Linan and Fayolle, 2015). The latter constitute the participants in this research study amongst undergraduate business students in the UAE. This will be further expanded upon in the section below on methodology. Furthermore this research contributes to the body of knowledge by developing two models for investigation, one of which researches how cognitive processes affect entrepreneurial intention; this type of investigation is limited in literature (Sanchez, 2013).

A Theoretical Model-Model A

In Model A, shown in Figure 1, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms are what drive the entrepreneurial intentions (Bandura, 1988; Casrud and Brannback, 2011; Krueger et al., 2000). Perceived behavioural control is the level of assurance an individual has about their ability to perform a behaviour based on how easy or difficult they perceive performance as it relates to limitations or facilitators (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen et al., 2004). Any person intending to perform behaviour takes into account the possible obstacles and whether he/she is able to effectively deal with them (Ajzen, 1991). Subjective norms are a person’s perception of significant others’ (family, friends, teachers, mentors etc.) beliefs that he or she should or should not perform the behaviour (Ajzen, 1991).

Figure 1: Model A: Perceived Behavioural Control And Subjective Norms Drive Entrepreneurial Intentions

The hypotheses in this model are:

Intentions are the most immediate antecedents of any behaviour that is under voluntary control and are assumed to capture the motivational influences on behaviour (Kiriakidis, 2015). Bird (1988) defined entrepreneurial intention as a state of mind driving a person to reach a goal which is the creation of a new venture. Bird (1988) continues to write that such intention is the blend of rational, analytic, cause-effect thinking and intuitive, holistic, contextual thinking. Entrepreneurial intention in psychological research is described as the link between the idea and action as well as the best predictor for entrepreneurial activity (Carsrud and Brannback, 2011).

Dinc and Budic (2016) in a study carried out with women on female entrepreneurship confirmed the positive effect of perceived behavioural control on entrepreneurial intentions that had already been researched by other authors (Bandura, 1988; Casrud and Brannback, 2011; Krueger et al., 2000; Lortie and Castogiovanni, 2015). Findings by Dinc and Budic (2016) show that if women have higher beliefs about their abilities and skills to control the process of creating and running a company their entrepreneurial intentions will increase. This study also confirmed the positive effect of subjective norms on entrepreneurial intentions stating that subjective norms have a strong influence on women’s attitudes towards entrepreneurship, as well as on the belief that they can create and manage to establish new companies or businesses.

In this model, motivation is what links the intentions to the cognitive planning and actual actions. This is not a linear process and motivation is that spark that transforms intention into action (Carsrud and Brannback, 2011) or cognitive planning in this study. As Barba-Sanchez and Atienza-Sahuquillo (2012) concluded “new ventures are created not only by those who can do it -this is, by the people that are able to do it-, but also those who have the required motivation to do that”. Palamida (2016) also looked at the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and motivation from an Expectancy Theory point of view and concluded that individuals form entrepreneurial intentions and then decide to engage in entrepreneurial behaviour based on specific rewards that they expect to gain and which are believed to fulfil their personal needs and desires. Therefore confirming the work by Herron and Robinson’s (1993) that any analysis of entrepreneurial behaviour must consider the influence of motivation.

The hypothesis in this model (Table 1) that entrepreneurial intentions influence outcome expectations has been tested by Pfeifer et al. (2016) in a study with students in Croatia that resulted in the finding that higher entrepreneurial intentions result in stronger entrepreneurial identity, higher self-efficacy and higher entrepreneurial outcome expectations.

| Table 1 Model A Hypothesis Statements |

|

| Hyp | Hypothesis Statement |

| H1a | Perceived Behavioural Control will significantly influence respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention |

| H2 | Subjective Norms will significantly influence respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention |

| H3 | Respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention significantly influences Cognitive Planning |

| H4a | Respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention significantly influences valence |

| H4b | Valence significantly influences Cognitive planning |

| H4 | Valence mediates the relationship between EI and Cognitive planning |

| H5a | Respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention significantly influences Expectations form the performance |

| H5b | Respondent outcome Expectations significantly influences Cognitive planning |

| H4 | Expectations mediate the relationship between EI and Cognitive planning |

Finally, everything we think say or do is as a result of mental processes (Baron, 2004). The cognitive processes researched in this study are the basis for any entrepreneurial activity that result from the perceived behavioural control that leads to entrepreneurial intention that is in turn stimulated by motivation. Hayton and Cholakova (2012) stated that no entrepreneurial opportunity and action will come about without the entrepreneurial cognitive planning process. Cognitive planning is a mental representation of the future enabling the entrepreneur also not to give up (Perwin, 2003). Gollwitzer (1996) adds that together with the mental strategy one also requires the overcoming of volitional problems that may be overcome through motivation. Cognitive planning facilitates the achievement of entrepreneurial goals as it guides people’s attention towards opportunities. Optimism increases with cognitive planning as well as the reduction of barriers experienced as a new entrepreneur (Gollwitzer, 1996).

An Alternative Theoretical Model-Model B

In Model B cognitive planning is the result of perceived behavioural control and subjective norms, and is considered to precede entrepreneurial intentions (Figure 2). This model is based on the work by Gollwitzer (1993) and Mantyla (1993) who claim that cognitive planning has an important role in shaping intentions and increases the intention-behavior consistency. Cognitive planning also increases the perceived behavioural control (Gillholm et al., 1999).

The hypotheses in this model are:

Entrepreneurship in the alternative model is viewed a way of thinking (Krueger et al., 2000) and it is cognitive planning that results in intention which is the cognitive state immediately prior to performing behaviour (Krueger, 2003). Essentially, behaviour is intentional if it is not the result of a stimulus-response relation, and any planned behaviour is intentional (Sanchez, 2013).

The assumption in this respect is that entrepreneurs possess a thought structure in relation to entrepreneurship that is significantly better than that of non-entrepreneurs (Sanchez, 2013). Research on how cognitive processes affect entrepreneurial intention is limited in research. In a study carried out by Sanchez (2013) results show that cognitive planning increases the level of entrepreneurial intentions.

The hypothesis in Table 2 that expectations significantly influence entrepreneurial intentions is supported by Jeong and Choi, (2017) in a study carried out with artists on Entrepreneurial intentions. They concluded that outcome expectations do influence entrepreneurial intentions as such expectations have a mediating effect on the relationship between job satisfaction and entrepreneurial intention.

| Table 2 Model B-Hypothesis Statements |

|

| Hyp | Hypothesis Statement |

| H1a | PBC significantly influences Cognitive Planning |

| H2 | Subjective Norms will significantly influence Cognitive Planning |

| H3 | Cognitive Planning significantly influences EI |

| H4a | Cognitive Planning significantly influences valence |

| H4b | Valence significantly influences Entrepreneurial intention |

| H4 | Valence mediates the relationship between EI and Cognitive planning |

| H5a | Cognitive Planning significantly influences Expectations form the performance |

| H5b | Expectations significantly influences Entrepreneurial intention |

| H5 | Expectations mediate the relationship between Cognitive planning and Entrepreneurial Intention |

Also Ratten (2016) found support for the hypothesis that outcome expectations significantly influence entrepreneurial intentions in a study carried out with female entrepreneurs they concluded that innovation outcome expectation amongst female entrepreneurs is positively related to intention to start an informal business.

Methodology

The methodology adopted in this research study is a quantitative in nature, utilizing a survey instrument to collect data in order to research the variables of perceived behavioural control, entrepreneurial intentions, motivation and cognitive planning. A quantitative method was selected to confirm the hypothesis in this research and it was deemed to be the best method to compare more than one variable.

The questionnaire was constructed for the purpose of this study and comprised a first section with 8 general questions addressing demographic variables namely, age, level of studies, specialization, employment, entrepreneurship activity, entrepreneurship activity amongst family members, entrepreneurship activity amongst female family members and educational courses taken in entrepreneurship. Another section was included with 50 items addressing perceived behavioural control, entrepreneurial intentions, motivation (expectancy, valence and instrumentality) and cognitive planning. In constructing the latter, questionnaire items were selected from tests that had already been used and tested for validity and reliability. Respondents were asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 related to “Strongly Disagree” and 5 to “Strongly Agree”.

The participants in this study were 337 undergraduate female Emirati students from Dubai and the northern emirates. The female Emirati students received a hard copy of the confidential questionnaire and were informed that the study was about entrepreneurship amongst female entrepreneurs in the UAE. Anonymity of both the respondents and institutions was promised to participants.

Results

In this section the findings following data analysis are presented in stages. Firstly, the overall descriptive statistics of the data items and the results of data validation including Chronbach alpha (Table 1), the Exploratory and Confirmatory factor analysis are shown that resulted from analysis using the SPSS software package. The hypotheses testing and the comparison for both of the two competing models that follows were done using the AMOS SEM package.

Validation of the Constructs

The scale reliability shows that all scale items work together to measure their respective construct, with all coefficients above the 0.7 threshold. The results of the analysis are presented in Table 3 below.

| Table 3 Scale Reliability Analysis Of The Scale Items In The Study Using Chronbach Alpha |

|

| Entrepreneurial Intentions | Chr. a |

| EI1-I am ready to do anything to become an entrepreneur | 0.807 |

| EI2-My professional goal is to be an entrepreneur | |

| EI3-I will make any effort to start and run my own business | |

| EI4-I am determined to create a business venture in the future | |

| Cognitive Planning | Chr. a |

| CP1-I have thought about developing a product/service for my business | 0.772 |

| CP2-I have considered looking for a location or equipment for my business idea | |

| CP3-I have worked on a business plan for my business idea | |

| CP4-I am thinking about saving money for my business | |

| CP5-I am thinking about funding for my business | |

| Perceived Behavioural Control | Chr. a |

| PBC1-It would be easy for me to start a business | 0.712 |

| PBC2-I am able to control the creation process of a business | |

| PBC3-I am prepared to do anything to become an entrepreneur | |

| PBC4-I have enough support to start a business | |

| PBC6-My level of knowledge is enough for me to start a business | |

| Performance Expectancy | Chr. a |

| E2-A career as an entrepreneur is totally attractive to me | 0.785 |

| E3-If I have the opportunity and resources I would like to start a business | |

| E4-Among various options I would rather be an entrepreneur | |

| E5-Being an entrepreneur would give me great satisfaction | |

| E6-I want to be my own boss | |

| Subjective Norms | Chr. a |

| SN1-My parents are positively oriented towards my future career as an entrepreneur. | 0.645 |

| SN2-My friends see entrepreneurship as a logical choice for me. | |

| SN3-I believe that people, who are important to me, think that I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur | |

| Valence | Chr. a |

| V3-Becoming a leader is attractive to me | 0.829 |

| V6-Exploring my talent interests me | |

| V7-Achieving higher status is important to me | |

| V8-Do something creative and innovative interests me | |

| V9-Being independent is important to me | |

| V11-Increasing my self-confidence is important to me | |

An exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to ensure convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. The exploratory factor analysis was done using the IBM SPSS package while the confirmatory factor analysis was done using and SEM model in AMOS SEM package. The results from the factor analysis are included in Appendix A

Hypotheses Testing

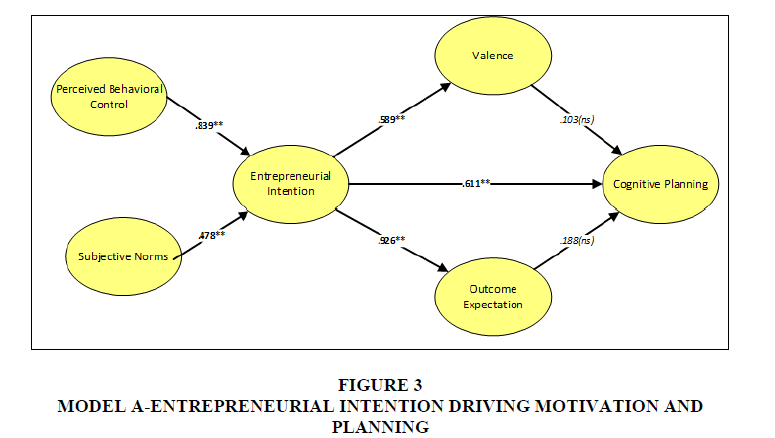

The main mechanism (Model A) was operationalized where Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) acts as a driver for Valence and Outcome expectancy, which in turn builds the cognitive planning in entrepreneurs using an SEM test of our hypotheses. The results from the hypotheses tests of the main model are presented below (Table 4), followed by a figure (Figure 3) of the mechanism being tested.

| Table 4 Main Model Hypotheses Tests |

||||

| Hyp | Hypothesis Statement | Estimate | SE. | Support |

| H1a | Perceived Behavioural Control will significantly influence respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.839** | 0.109 | Yes |

| H2 | Subjective Norms will significantly influence respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.478** | 0.067 | Yes |

| H3 | Respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention significantly influences Cognitive Planning | 0.611** | 0.096 | Yes |

| H4a | Respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention significantly influences entrepreneurial Valence | 0.589** | 0.108 | Yes |

| H4b | Valence significantly influences Cognitive Planning | 0.103 (ns) | No | |

| H4c | Valence mediates the relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Cognitive planning | H4b (ns) | N/A | No |

| H5a | Respondents’ Entrepreneurial Intention significantly influences Expectations from the performance | 926** | 0.111 | Yes |

| H5b | Respondent outcome Expectations significantly influences Cognitive planning | 0.188 (ns) | No | |

| H5c | Expectations mediate the relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Cognitive planning | H5b (ns) | N/A | No |

| Note: *p<0.01; **p<0.001. | ||||

Perceived behavioural control shows strong support for Entrepreneurial Intention and subsequent relationships H1 is strongly supported. The test for H2, while significant, shows that Subjective Norms are a weaker influence on the formation of Intentions for Entrepreneurial activity than H1 where PBC is a stronger driver. The model shows that EI works to significantly influence the two modalities of motivation with both H4a and H5a very strongly significant. EI is also a strong influence of the development of Cognitive planning efforts of the entrepreneur (supporting H3). H4b and H5b were found to be non-significant, which indicates that the influence from Entrepreneurial intention on Cognitive planning is not mediated. EI supports Cognitive planning directly and is not mediated through Valence and Outcome Expectations, thus rendering hypotheses H4c and H5c also unsupported. The figure below (Figure 1) shows the results of the SEM for our main model. The lack of mediating relationships raises questions around model parsimony and whether Cognitive Planning as a driver for the development of Entrepreneurial intention (the alternative model) would provide better fit for the data we have collected.

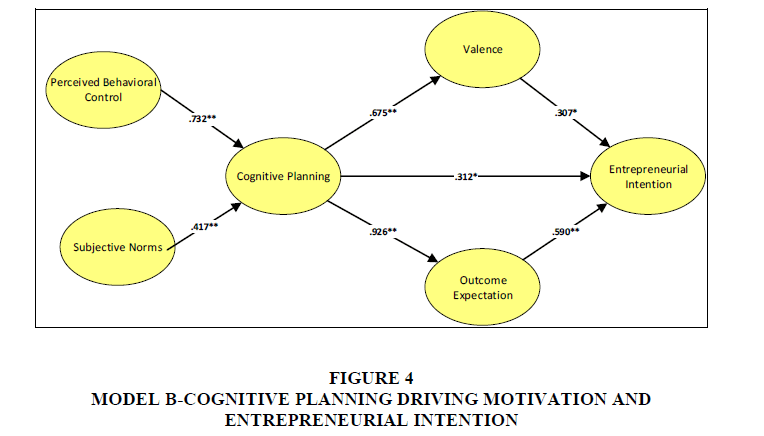

Our alternative model (Model B) was operationalized so that the mechanism between Entrepreneurial intention and cognitive planning is reversed. This tests an alternative mechanism where instead of being the driver, Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) is a resulting outcome which is supported by an initial development of Cognitive Plans. The presence of motivational drivers (modalities-Valence and Outcome expectancy), once again would mediate this relationship. We can consider this a nested model because the only change we are making is alternating the position of the EI and CP constructs.

SEM hypotheses tested by the alternative model are very similar to the main model. H1 and H2 are both significant showing that Perceived behavioural control and Subjective norms provide a strong support for the main mechanism, in this case, Cognitive planning, and the subsequent relationships. Again the estimated coefficient in H1 is stronger than the role of subjective Norms (H2), though both are clearly expressed. In this model we see that H3 is significant, showing the direct relationship of cognitive planning as it supports the development of entrepreneurial intention (estimated coefficient 0.312*).

Table 5 (below) present the results of the test of the alternative mechanism and is followed by a figure of the mechanism.

| Table 5 Alternative Model (B) Hypotheses Tests |

||||

| Hyp | Hypothesis Statement | estimate | SE. | Supp. |

| H1 | Perceived Behavioural Control will significantly influence respondents’ Cognitive Planning | 0.732** | 0.117 | yes |

| H2 | Subjective Norms will significantly influence respondents’ Cognitive Planning | 0.417** | 0.070 | yes |

| H3 | Respondents’ Cognitive Planning significantly influences Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.312* | 0.054 | yes |

| H4a | Respondents’ Cognitive Planning will significantly influences entrepreneurial Valence | 0.675** | 0.127 | yes |

| H4b | Valence significantly influences Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.307** | 0.052 | yes |

| H4 (all) | Valence mediates the relationship between Cognitive Planning and Entrepreneurial Intention | Supp. | yes | |

| H5a | Respondents’ Cognitive Planning will significantly influence Expectations from the performance | 0.926** | 0.154 | yes |

| H5b | Respondent outcome Expectations significantly influences Entrepreneurial Intention | 0.590** | 0.082 | yes |

| H5 (all) | Expectations mediates the relationship between Cognitive planning and Entrepreneurial Intention | Supp. | ||

| Note: *p<0.01; **p<0.001. | ||||

Hypotheses 4 a-c and 5 a-c carry out the test of mediating effects, given that H3 is also supported. The SEM analysis also shows coefficient estimates for H4a of 0.675 and H4b estimate of 0.307*, thus both hypotheses are supported. Having H3, H4a and H4b significant shows that while Cognitive Planning significantly drives Entrepreneurial intentions, and part of the influence of this relationship is transmitted through a mediating effect through Valence. Looking at the Outcome Expectations hypotheses H5a shows support with a significant coefficient estimate of 0.926, while H5b is also supported with an estimate of 0.590. Under the Alternative Model Performance/Outcome expectations also mediate the relationship between Cognitive Planning and Entrepreneurial Intention. The mediating effect of Outcome expectations is even stronger than the mediating effect of Valence. Figure 4 provides an overview of the relationships and estimated coefficients by the Alternative model.

The model fit statistics for the two competing models being tested are within the accepted levels. The RMSEA is .056, and support indices all show that the model is a good fit for the data that has been collected.

Table 6 (below provides a full listing of the model fit indices of the constructs in the tested models.

| Table 6 Fit Indices From The Cfa Analysis |

||

| Fit Indices | coeff. | |

| Norm. fit index | NFI | 0.878 |

| Relative fit index | RFI | 0.819 |

| Incremental fit | IFI | 0.935 |

| Tucker-Lewis | TLI | 0.900 |

| Comparative fit | CFI | 0.933 |

| RMSEA | 0.056 | |

| Chi sq. /DF | 440.887/229 | |

| P for close fit | <0.0000 | |

Discussion

The theory of planned behaviour, stating that entrepreneurial behaviour is the result of intentions to perform a behaviour, perceived control over the behaviour and subjective norms (Ajzen, 1991), continues to find support in this research study in both Models A (the hypothesis) and B (the alternate hypothesis). Findings show that intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activity as well as any planning at a cognitive level are all preceded by the assurance people have about their ability to be entrepreneurs (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen et al., 2004) and their perception of significant others’ (family, friends, teachers, mentors etc.) beliefs that they should or should become an entrepreneur (Ajzen, 1991).

In Model A, where entrepreneurial intentions precede cognitive planning, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms are significantly linked to entrepreneurial intentions which are in turn significantly linked to the mental process of cognitive planning. In Model B, where cognitive planning precedes entrepreneurial intentions, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms are also significantly linked to cognitive planning which in turn is significantly linked to entrepreneurial intentions.

The differences in results in investigating Model A and Model B occur when the mediating variable of motivation is introduced. Motivation studied within the theoretical framework of the Expectancy Theory fits best with the alternative hypothesis (Model B). In Model B both valence and outcome expectations significantly influence the relationship between cognitive planning and entrepreneurial intentions. However in Model A valence and outcome expectations do not significantly influence the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and cognitive planning.

The effect of cognitive planning on valence and outcome expectations was also researched by Adomako et al. (2016) who found similar results those entrepreneurs scoring high on optimistic expectations also exhibit high levels of cognitive planning therefore also supporting the hypothesis that cognitive planning influences outcome expectations. In addition, Jeong and Choi (2017) in a study carried out with artists on Entrepreneurial intentions concluded that outcome expectations do influence entrepreneurial intentions as such expectations have a mediating effect on the relationship between job satisfaction and entrepreneurial intention.

Also in relation to Model B, Ratten (2016) found support for the hypothesis that outcome expectations sand valence significantly influence entrepreneurial intentions in a study carried out with female entrepreneurs Ratten (2016) concluded that innovation outcome expectation amongst female entrepreneurs is positively related to intention to start an informal business.

The finding relating to Model A that valence and outcome expectations do not significantly influence the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and cognitive planning is also supported by Townsend et al. (2010) who state that it is ability expectancies that strongly predict new venture start-up mental planning and not outcome expectancies as the later only play a marginal role.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the fit between the theories of planned behaviour and the motivation theory the Expectancy theory works best when cognitive planning is understood as the shaper of entrepreneurial intentions that increases the intention-behaviour consistency (Gollwitzer, 1993; Mantyla, 1993; Gillholm et al., 1999).

The recommendation by Herron and Robinson (1993) that any analysis of entrepreneurial behaviour must consider the influence of motivation finds support in this research study however the fit between theories works best when cognitive planning is studies as the variable that increases the level of entrepreneurial intentions. This finding is also in line with previous findings by Sanchez (2013) who also concluded that cognitive planning increases the level of entrepreneurial intentions who however had not introduced the mediating variable of motivation.

A theoretical implication of this study is that there exists a significant fit between the theory of planned behaviour and the expectancy theory. However when two theories are introduced within a hypothesis, the theory of planned behaviour and the expectancy theory in this study, the relationship between variables may change. In this study the cognitive processes of the entrepreneur take centre stage of importance and significance when the mediating variable of motivation is introduced. An implication for research resulting from this study is that the integration of theories in research may shed light on the interaction between variables that may challenge previously supported hypothetical statements. Furthermore a practical implication is the emphasis on cognitive processes in forming and supporting nascent entrepreneurs.

Research on how cognitive processes affect entrepreneurial intention is limited in research. A recommendation for research is to investigate further the assumption made by Sanchez (2013) that entrepreneurs possess a thought structure in relation to entrepreneurship that is significantly better than that of non-entrepreneurs.

A limitation of this study is that it was carried out with a homogenous group of participants, namely female undergraduate Emirati. A recommendation is to repeat this research study with both male and female participants within a more heterogeneous group.

A practical recommendation is that in encouraging and training potential entrepreneurs institutions need to focus on cognitive planning which is a skill that may be learnt. Having these skill individuals who are motivated to become entrepreneurs will be better equipped in the stages of forming more concrete entrepreneurial intentions. The multi-disciplinary teams assisting new entrepreneurs may include specialists in cognitive psychology.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality and behavior. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179.

- Ajzen, I., Brown, T.C., & Carvajal, F. (2004). Explaining the discrepancy between intentions and actions: The case of hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1108- 1121.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Engle-wood Cliffs: Prentice.

- Ajzen, I., & Madden, T.J. (1986). Prediction of goal directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions and perceived behavioual control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 453-474.

- Armitage, C.J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, (471-499).

- Bandura, A. (1988). Perceived self-efficacy: Exercise of control through self-belief. In J. P. Dauwalder, M. Perrez, & V. Hobi (Eds.), Annual Series of European Research in Behavior Therapy, (pp.27-59). Amsterdam/Lisse, Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

- Barba-Sánchez, V., & Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2012). Entrepreneurial behavior: Impact of motivation factors on decision to create a new venture. Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 18(2), 132-138.

- Baron, R.A. (2004). The cognitive perspective: A valuable tool for analysing entrepreneurship’s basic Why Questions. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 221-239.

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. The Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442-453.

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9-26.

- Chuluunbaatar, E., Ding Bang Luh, O., & Kung, S. (2011). The entrepreneurial start-up process: The role of social capital and the social economic condition. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 16(1), 43-71.

- Conner, M, Norman P., & Bell, R. (2002). The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychology, 21(2), 194-201.

- Dinc, M.S., & Budic, S. (2016). The impact of personal attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control on entrepreneurial intentions of women. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 9(17), 23-35.

- Douglas, E.J., & Shepherd, D.A. (2000). Entrepreneurship as a utility maximizing response. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(3), 231-251.

- Edelman, L.F., Brush, C.G., Manolova, T.S., & Greene, P.G. (2010). Start‐up motivations and growth intentions of minority nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(2), 174-196.

- Gillholm, R., Ettema, D., Selart, M., & Garling, T. (1999). The role of planning for intention-behavior consistency. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40(4), 241-250.

- Gollwitzer, P.M. (1996). The volitional benefits of planning. In P.M. Gollwitzer & J.A. Bargh (Eds.), The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior (287-312). New York: Guilford.

- Guzmán-Alfonso, C., & Guzmán-Cuevas, J. (2012). Entrepreneurial intention models as applied to Latin America. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 25(5), 721-735.

- Hayton, J.C., & Cholakova, M. (2012). The role of affect in the creation and intentional pursuit of entrepreneurial ideas. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 41-68.

- Herron, L., & Robinson, R.B. (1993). A structural model of the effects of entrepreneurial characteristics on venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(3), 281-94.

- Jeong, J., & Choi, M. (2017). The expected job satisfaction affecting entrepreneurial intention as career choice in the cultural and artistic industry. Sustainability, 9, 2-16.

- Kautonen, T., Down, S., & Minniti, M. (2013). Ageing and entrepreneurial preferences.

- Kiriakidis, S. (2015). Theory of planned behaviour: The intention-behaviour relationship and the perceived behavioural control (PBC) relationship with intention and behaviour. International Journal of Strategic International Marketing, 2(3).

- Kolvereid, L. (1996b). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47-56.

- Kolvereid, L. (1996b). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47-56.

- Kolvereid L. (1996b). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 12(1), 5-20.

- Kolvereid L., & Isaksen E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866-885.

- Krueger, A.B. (2003). Economic considerations and class size. Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society, 113(485), F34-F63.

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., & Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411-432.

- Lanero, A., Vazquez, J., Gutierrez, P., & Purificacion Garcia, M. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurship education in European universities: an intention-based approach analyzed in the Spanish area. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 8(5), 111-130.

- Langevang T. (2008). We are managing uncertain paths to respectable adulthoods in Accra Ghana. Geoforum, 39(6), 2039-2047.

- Linan, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses and research agenda. International Entrepreneurial Management Journal, 11, 907-933.

- Lortie, J., & Castogiovanni, G.J. (2015). The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management, 2015.

- Mantyla, T. (1996). Ativating actions and interrupting intentions: Mechaisms of retireival sensitization in prospective memory. In M.A. Brandimonte and G. O. Einstein (Eds.), Prospective Memory: Theory and Applications (pp.93-114). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Orser, B., & Hogarth-Scott, S. (2003). Opting for growth: Gender dimensions of choosing enterprise development. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 19(3), 284-300.

- Perwin, L. (2003). The science of personality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pfeifer, S., Šarlija, N., & Sušac, M.Z. (2016). Shaping the entrepreneurial mindset: Entrepreneurial intentions of business tertiary students in Croatia. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 102-117.

- Palamida, E. (2016) Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: The interrelated role of background, situational and psychological factors. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Newcastle University Business School, Newcastle, UK.

- Ratten, V. (2016) Female entrepreneurship and the role of customer knowledge development, innovation outcome expectations and culture on intentions to start informal business ventures. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 27(2), 262-272

- Renko, M., Kroeck, K.G., & Bullough, A. (2012). Expectancy theory and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 667-684.

- Robbins, S.P., & Judge, T.A. (2013). Organisational behaviour. Pearrson: NY.

- Sanchez, J.C. (2013). The impact of an entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurial competencies and intention. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3): 447-465.

- Soomro, B.A., & Shah, N. (2014). Cultural factors and entrepreneurial intention: The role of entrepreneurship education. Education and Training, 56(9), 680-696.

- Tkashev, A., & Kolvereid, L. (1999). Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 11, 269-280.

- Turner, S., & Nguyen, P.A. (2005). Young entrepreneurs, social capital and Doi Moi in Hanoi, Vietnam. Urban Studies, 42(10), 1693-1710.

- Vroom, V.H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley: NY.

- Wiklund, J., Davidsson, P., & Delmar, F. (2003). Expected consequences of growth and their effect on growth willingness in different samples of small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(3), 247-269.

- Zimmerer, T.Z., & Scarborough, N.M. (2005). Essentials of entrepreneurship and small business management, (4th edition). Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.